LOQ and Signal-to-Noise Ratio: A Complete Guide for Robust Bioanalytical Method Validation

This article provides a comprehensive guide to the Limit of Quantitation (LOQ) and its critical relationship with the signal-to-noise (S/N) ratio, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

LOQ and Signal-to-Noise Ratio: A Complete Guide for Robust Bioanalytical Method Validation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to the Limit of Quantitation (LOQ) and its critical relationship with the signal-to-noise (S/N) ratio, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. It covers foundational principles, detailing how LOQ defines the lowest concentration of an analyte that can be quantified with acceptable precision and accuracy, and why a S/N ratio of 10:1 is the established standard. The content explores methodological approaches for calculating LOQ according to ICH Q2(R1) guidelines, including practical examples from chromatographic analysis. It further addresses common challenges and optimization strategies to enhance S/N ratios, and concludes with essential validation protocols and a comparative analysis of different LOQ determination methods to ensure regulatory compliance and method reliability in pharmaceutical and clinical settings.

LOQ and Signal-to-Noise Demystified: Core Concepts and Regulatory Definitions

In analytical chemistry, the Limit of Quantitation (LOQ), also known as the Limit of Quantification, represents the lowest concentration of an analyte that can be reliably measured with acceptable precision and accuracy under stated experimental conditions [1]. It serves as a fundamental figure of merit that defines the lower boundary of an analytical method's quantitative range. LOQ is distinguished from the Limit of Detection (LOD), which represents the lowest concentration that can be detected but not necessarily quantified with acceptable precision [2] [3]. While LOD answers the question "Is it there?", LOQ answers "How much is there?" with statistical confidence.

The establishment of a robust LOQ is critical for regulatory compliance and quality control across pharmaceutical, environmental, and food safety testing [1]. For drug development professionals, accurately determining LOQ ensures that trace-level impurities and degradation products can be properly quantified, directly impacting product safety profiles and regulatory submissions. The clinical and laboratory standards institute (CLSI) defines LOQ as the lowest concentration at which an analyte can not only be reliably detected but also meet predefined goals for bias and imprecision [2].

Key Concepts and Definitions

Relationship Between LOQ, LOD, and LoB

Understanding LOQ requires differentiation from two related concepts: Limit of Blank (LoB) and Limit of Detection (LOD). These three parameters establish a hierarchy of detection capabilities:

Limit of Blank (LoB): The highest apparent analyte concentration expected to be found when replicates of a blank sample containing no analyte are tested [2]. It represents the background noise level of the analytical system and is calculated as: LoB = meanblank + 1.645(SDblank) assuming a Gaussian distribution [2].

Limit of Detection (LOD): The lowest analyte concentration likely to be reliably distinguished from the LoB [2]. It represents the threshold at which detection is feasible but quantification remains unreliable. Per ICH guidelines, LOD is typically determined using a signal-to-noise ratio between 2:1 and 3:1 [4].

Limit of Quantitation (LOQ): The lowest concentration at which the analyte can be reliably detected and quantified with predefined levels of bias and imprecision [2]. The LOQ may be equivalent to the LOD or at a much higher concentration, but it cannot be lower than the LOD [2].

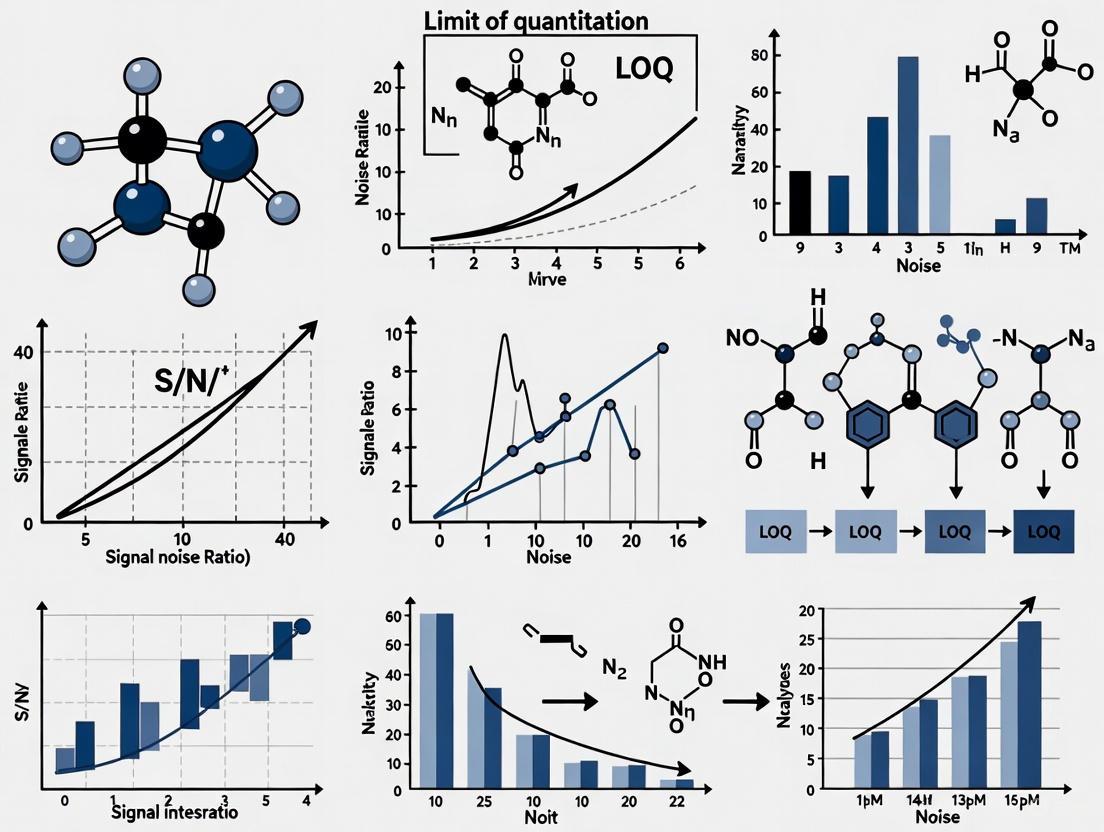

The relationship between these parameters is visually represented in the following conceptual diagram:

Regulatory Definitions and Requirements

Multiple regulatory bodies provide specific guidance on LOQ determination:

ICH Q2(R1) Guidelines: Define LOQ as having a typical signal-to-noise ratio of 10:1 [4]. The upcoming ICH Q2(R2) revision maintains this standard while potentially tightening LOD requirements [4].

CLSI EP17 Protocol: Provides standardized approaches for determining LoB, LOD, and LOQ, recommending 60 replicates for establishing these parameters and 20 for verification [2].

Pharmacopeial Standards: USP and other pharmacopeias reference LOQ requirements for validated analytical methods, particularly for impurity testing [3].

Calculation Methods and Experimental Protocols

Standard Approaches to LOQ Determination

Multiple established methods exist for determining LOQ, each with specific applications and limitations:

Table 1: Comparison of LOQ Calculation Methods

| Method | Formula/Approach | Typical Replicates | Best Suited For | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Signal-to-Noise Ratio | LOQ = Concentration at S/N ≥ 10:1 [1] [4] | 6-20 determinations [3] | Chromatographic methods with baseline noise [4] | Simple, quick; requires visual inspection of chromatograms [4] |

| Standard Deviation of Blank | LOQ = meanblank + 10 × SDblank [3] | Minimum 10 blank replicates [3] | Methods with measurable blank response | May overestimate LOQ if blank variability is high [5] |

| Standard Deviation of Response and Slope | LOQ = 10σ/Slope [3] | 6+ determinations at 5+ concentrations [3] | Quantitative assays without significant background noise [3] | Accounts for calibration curve characteristics; σ = standard deviation of response [3] |

| Visual Evaluation | Logistics regression for probability of detection [3] | 6-10 determinations per concentration [3] | Visual methods (color change, precipitation) | Subjective; LOQ typically set at 99.95% detection rate [3] |

| Propagation of Errors | Complex formula accounting for uncertainty in slope and intercept [5] | Varies with required confidence | High-accuracy requirements | Most statistically rigorous; accounts for multiple error sources [5] |

Detailed Experimental Protocol for LOQ Determination

For researchers establishing LOQ, the following workflow provides a systematic approach:

A robust LOQ determination protocol includes these critical steps:

System Preparation and Calibration: Ensure all instruments are properly calibrated and stabilized. For HPLC systems, this includes verifying detector linearity, pump stability, and column performance [1] [6].

Blank Analysis: Analyze multiple blank samples (minimum 10, ideally 20-60) to establish the baseline characteristics and calculate LoB [2] [3]. The blank matrix should match actual samples as closely as possible.

Low-Concentration Standard Preparation: Prepare standards at 5-7 concentration levels spanning the expected LOQ region. Use appropriate dilution techniques to minimize preparation errors [3] [6].

Sample Analysis with Replication: Analyze 6-20 replicates of each concentration level in randomized order to account for instrumental drift [2] [3].

Data Collection: Precisely measure analyte signals and baseline noise in regions adjacent to the analyte peak. For chromatographic methods, ensure peak-free sections are selected for noise measurement [4].

LOQ Calculation: Apply the chosen calculation method consistently. The signal-to-noise method requires LOQ to have S/N ≥ 10:1, while the standard deviation method uses the concentration where RSD ≤ 20% for precision and 80-120% recovery for accuracy [1] [2].

Experimental Verification: Confirm the calculated LOQ by analyzing multiple samples at this concentration. The method should demonstrate ≤20% RSD and 80-120% accuracy at the LOQ [1] [6].

Research Reagent Solutions for LOQ Studies

Table 2: Essential Materials for LOQ Determination Experiments

| Reagent/Material | Function in LOQ Studies | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| High-Purity Reference Standards | Quantitation benchmark | Purity ≥ 99.5%; proper storage conditions; verification of stability [6] |

| Matrix-Matched Blank Samples | Establishing baseline noise | Should mimic actual sample composition without analyte [6] |

| HPLC-Grade Solvents | Mobile phase preparation | Low UV cutoff; minimal particulate matter; fresh preparation [1] |

| Certified Reference Materials | Method verification | Traceable to national standards; validated concentration values [3] |

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Analytes | Internal standards for MS detection | Minimal isotopic interference; similar retention behavior [7] |

Comparative Analysis of LOQ Across Analytical Techniques

Method-Specific LOQ Considerations

LOQ determination varies significantly across analytical platforms:

HPLC with UV Detection: Typically uses signal-to-noise ratio (10:1) for LOQ determination. Sensitivity depends on detector characteristics, with diode array detectors providing superior linearity range for impurity quantification [4].

Gas Chromatography: Classical IUPAC methods using standard deviation of blank may overestimate LOQ; propagation of errors methods provide more accurate estimates [5].

Spectroscopic Techniques (LIBS): Multivariate analysis (MVA) models require specialized LOQ calculations that account for model complexity and chemical matrix effects [7].

Pharmaceutical Potency Assays: According to ICH Q2, LOD/LOQ determinations are not required for potency assays, as they operate at much higher concentrations [3].

Factors Influencing LOQ Values

Multiple factors impact the achievable LOQ in analytical methods:

Instrumental Noise: Electronic and detector noise directly impacts baseline stability. Modern instruments with lower noise specifications enable lower LOQs [4] [5].

Sample Matrix Effects: Complex matrices can suppress or enhance analyte signals. Matrix-matched standards and effective sample preparation minimize these effects [1] [6].

Sample Preparation Techniques: Pre-concentration methods like solid-phase extraction or liquid-liquid extraction can lower practical LOQs by increasing analyte concentration [6].

Data Treatment Approaches: Mathematical smoothing functions (Savitsky-Golay, Fourier transform) can reduce noise but risk over-smoothing and signal loss if applied excessively [4].

Advanced Topics and Method Optimization

Improving LOQ Through Method Optimization

When default LOQ values are insufficient for application requirements, several optimization strategies can be employed:

Increasing Sample Concentration: Pre-concentration techniques like evaporation, solid-phase extraction, or liquid-liquid extraction can effectively lower method LOQs [6].

Instrument Parameter Optimization: Adjusting detector settings (e.g., time constant in UV detection), signal integration time, or injection volume can enhance sensitivity [4] [6].

Alternative Detection Techniques: Switching to more sensitive instrumentation (e.g., LC-MS/MS instead of UV detection, ICP-MS instead of AAS) can significantly lower LOQs [6].

Background Reduction Techniques: Matrix matching, baseline subtraction, and signal averaging minimize interference and improve effective LOQs [6].

Regulatory and Practical Considerations

LOQ determination must balance statistical rigor with practical utility:

Reporting Significant Figures: Due to the inherent 10-20% RSD at LOQ, values should be reported to one significant digit only. Reporting excessive significant figures implies false precision [5].

Method Validation Requirements: For regulated environments, LOQ must be demonstrated using predefined acceptance criteria (typically precision ≤20% RSD and accuracy 80-120%) [1] [2].

Transfer Between Instruments: LOQ values are method- and instrument-specific. Verification is required when transferring methods between laboratories or instrument platforms [4].

The Limit of Quantitation represents a fundamental parameter establishing the lower quantitative boundary of analytical methods. Its accurate determination through standardized protocols ensures reliable quantification of trace analytes in pharmaceutical, environmental, and clinical applications. The appropriate selection of calculation methods—whether signal-to-noise ratio, standard deviation approaches, or propagation of errors—depends on the specific analytical technique and matrix characteristics. As analytical technologies advance, with instruments offering lower baseline noise and improved detection capabilities, LOQ values continue to decrease, enabling scientists to quantify increasingly lower analyte concentrations with statistical confidence. For drug development professionals, robust LOQ determination remains essential for method validation, regulatory compliance, and ultimately, ensuring product safety and efficacy.

In analytical chemistry, the Limit of Quantitation (LOQ) represents the lowest concentration of an analyte that can be quantitatively determined with acceptable precision and accuracy under stated methodological conditions [8]. The establishment of a reliable LOQ is fundamental across numerous scientific fields, particularly in pharmaceutical analysis and environmental monitoring, where the accurate quantification of trace-level impurities, contaminants, or active compounds is critical for product safety and regulatory compliance. The signal-to-noise (S/N) ratio is a pivotal concept directly linked to determining this limit, providing a practical and widely accepted means to assess the performance and sensitivity of an analytical method [4] [9].

The S/N ratio is a measure that compares the level of a desired analytical signal to the level of background noise [10]. In techniques like High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC), the signal is typically the height of the analyte peak, while the noise is the amplitude of the baseline fluctuation in a peak-free region of the chromatogram [4] [9]. A higher S/N ratio indicates a clearer, more distinguishable analyte signal, which translates to greater reliability in both detecting and quantifying the substance of interest. While various approaches exist for determining the LOQ, including those based on the standard deviation of the blank and the slope of the calibration curve, the S/N ratio method remains one of the most intuitive and commonly applied, especially in chromatographic analyses [8] [11]. This article explores the justification behind the international consensus that establishes a 10:1 S/N ratio as the gold standard for the Limit of Quantitation.

The 10:1 Standard - Rationale and Regulatory Acceptance

The Statistical and Practical Basis for the 10:1 Ratio

The establishment of a 10:1 signal-to-noise ratio for the LOQ is not arbitrary; it is rooted in the requirement for a minimum level of precision and accuracy in quantitative measurements. The relationship between S/N and method precision can be summarized by a practical rule of thumb: %RSD ≈ 50 / (S/N), where %RSD is the percent relative standard deviation (a measure of imprecision) [9]. According to this relationship, an S/N of 10 corresponds to an expected precision of approximately 5% RSD, which is generally considered acceptable for quantitative work at the limit of quantification [9].

This 10:1 ratio provides a sufficient buffer to ensure that the analyte signal is robustly distinguishable from the inherent baseline noise of the analytical system. This distinction is crucial for minimizing quantitative errors. At lower S/N ratios, the relative impact of noise on the integrated peak area or height becomes more significant, leading to higher uncertainty and poorer reproducibility in measurement results [8]. The 10:1 threshold ensures that the signal strength is an order of magnitude greater than the background noise, thereby providing a fundamental guarantee of reliability for the quantitative data produced.

International Regulatory Endorsement

The 10:1 S/N criterion for LOQ has been widely adopted by major international regulatory bodies, solidifying its status as a gold standard. The International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) Guideline Q2(R1) on the validation of analytical procedures explicitly states that the LOQ is the concentration at which the signal level of the analyte reaches at least 10 times the signal noise of the baseline [4] [12]. This guideline is implemented by regulatory agencies worldwide, including the FDA in the United States, the European Medicines Agency (EMA), and the Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency (PMDA) in Japan [4].

Other pharmacopoeias, such as the United States Pharmacopeia (USP) and the European Pharmacopoeia, also describe and accept the signal-to-noise approach for determining quantification limits [13]. This broad regulatory consensus provides a unified and harmonized standard for the pharmaceutical industry, ensuring that analytical methods are validated consistently to produce reliable and comparable data across different laboratories and regions. For bioanalytical methods, where even greater variability is accepted, the Lower Limit of Quantification (LLOQ) is defined as the lowest calibration standard where the analyte response is at least five times that of the blank, and the precision and accuracy are within 20% [8]. This highlights that the specific S/N requirement can be adapted to the application's context, though the 10:1 ratio remains the benchmark for general chemical quantification.

Comparison of Detection and Quantitation Limits

Understanding the LOQ requires its distinction from the closely related Limit of Detection (LOD). Both parameters are fundamental figures of merit for an analytical method, but they serve different purposes and are characterized by different stringencies. The table below summarizes the key differences, with a focus on the S/N ratio criteria.

Table 1: A comparison of LOD and LOQ based on signal-to-noise ratio

| Feature | Limit of Detection (LOD) | Limit of Quantitation (LOQ) |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | The lowest concentration at which the analyte can be reliably detected, but not necessarily quantified [11]. | The lowest concentration that can be quantified with acceptable precision and accuracy [8] [11]. |

| Primary Purpose | Qualitative identification of the presence or absence of an analyte. | Quantitative determination of the analyte concentration. |

| Standard S/N Ratio | 3:1 [4] [11] [13] | 10:1 [4] [8] [12] |

| Implied Precision (%RSD) | ~15-20% or worse [9] | ~5% [9] |

| Regulatory Basis | ICH Q2(R1) states a 3:1 S/N is acceptable for estimating LOD [4]. | ICH Q2(R1) specifies a typical 10:1 S/N for LOQ [4] [11]. |

As the table illustrates, the LOQ demands a higher standard of performance than the LOD. The LOD answers the question, "Is the analyte there?" while the LOQ answers, "How much of the analyte is present, and with what confidence?" The three-fold higher S/N requirement for the LOQ (10:1 vs. 3:1) directly reflects the greater signal robustness needed for reliable quantification compared to mere detection [4]. In practice, this means that the LOQ of a method will always be at a higher concentration than its LOD.

Experimental Protocols for Determining LOQ by S/N

Standard Operating Procedure for S/N Measurement

The experimental determination of the S/N ratio in chromatographic systems follows a standardized, practical protocol. The following workflow outlines the key steps for manual measurement, which can also be performed automatically by modern Chromatography Data Systems (CDS) [4] [9].

Step-by-Step Protocol:

- Instrumental Setup: The analytical method (e.g., HPLC with UV detection) should be optimized and stabilized. A blank sample (lacking the analyte) is first injected to confirm a clean, stable baseline [9].

- Analysis of Low-Level Analytic: A reference solution or sample containing the analyte at a concentration near the expected LOQ is injected, and the chromatogram is recorded [13].

- Noise Measurement: A representative, peak-free section of the baseline in the chromatogram (from the blank or from the sample analysis itself) is selected. As per the illustrated workflow, the noise (N) is determined by drawing two lines tangentially to the maximum and minimum fluctuations of the baseline. The vertical distance between these two lines is the peak-to-peak noise [9] [13]. Some guidelines, like the European Pharmacopoeia, specify observing the noise over a distance equal to 20 times the peak width at half height [13].

- Signal Measurement: The signal (S) is the height of the analyte peak, measured from the midpoint of the baseline noise to the maximum of the peak [9].

- Calculation: The S/N ratio is calculated by simply dividing the measured signal (S) by the measured noise (N): S/N = S / N [9].

- Establishing the LOQ: A series of samples with decreasing concentrations of the analyte are analyzed. The LOQ is defined as the lowest concentration for which the calculated S/N ratio is equal to or greater than 10:1 [4] [11].

Alternative and Complementary Approaches

While the S/N ratio is a direct and common method, regulatory guidelines like ICH Q2(R1) acknowledge other approaches for determining LOQ [11]. These are often based on standard deviation and the slope of the calibration curve.

The formula for this approach is: LOQ = 10 × σ / S Where:

- σ = the standard deviation of the response (e.g., of the blank, the y-intercept of a regression line, or the residual standard deviation of the regression line).

- S = the slope of the analytical calibration curve [8] [11].

This method is particularly useful when a clear baseline for noise measurement is not obtainable or when a more statistical foundation is desired. The factor of 10 used in the formula is consistent with the 10:1 S/N ratio principle, as both aim to achieve a similar level of confidence in the quantitative result [11]. In practice, the LOQ determined by one method should be verified through the injection of actual samples at that concentration level to confirm that the predefined accuracy and precision criteria (e.g., ±20% for bias and imprecision at the LOQ level) are met [2] [8].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

The reliable determination of LOQ and the achievement of a robust S/N ratio depend on the use of high-quality materials and reagents. The following table details key solutions and consumables essential for these experiments.

Table 2: Key research reagent solutions and materials for LOQ/S/N experiments

| Item | Function & Importance |

|---|---|

| HPLC-Grade Solvents | High-purity solvents (acetonitrile, methanol, water) are critical for preparing mobile phases and samples. They minimize baseline noise and ghost peaks caused by UV-absorbing impurities [9]. |

| High-Purity Analytical Standards | Certified reference materials (CRMs) of the analyte with known purity and concentration are used to prepare accurate calibration solutions for establishing the analytical curve and determining the S/N ratio [8]. |

| Appropriate Matrix Blank | A real or artificial sample matrix that is free of the analyte. It is used to establish the baseline noise, determine the Limit of Blank (LoB), and prepare matrix-matched calibration standards to account for matrix effects [2] [8]. |

| Chemically Inert Vials & Vial Inserts | To prevent adsorption of the analyte onto container surfaces, especially at low concentrations, which could lead to inaccurate quantification and poor recovery. |

| Quality Chromatographic Column | A column with high chromatographic efficiency (theoretical plates) is essential for producing sharp, symmetrical peaks, which increases the signal (peak height) and thus improves the S/N ratio [9]. |

The 10:1 signal-to-noise ratio endures as the gold standard for defining the Limit of Quantitation due to its solid foundation in statistical reasoning, its direct correlation with acceptable analytical precision, and its widespread adoption by international regulatory authorities. This ratio provides a clear, practical, and universally understood benchmark that ensures quantitative data generated at the lowest levels of detection are reliable, accurate, and fit for their intended purpose, whether in drug development, environmental monitoring, or food safety. While mathematical smoothing techniques and advanced instrumentation can push detection capabilities lower, the 10:1 S/N threshold remains a fundamental criterion for validating any analytical method where confident quantification is the ultimate goal.

In analytical chemistry and clinical diagnostics, accurately measuring low concentrations of an analyte depends on understanding three critical performance thresholds: the Limit of Blank (LoB), the Limit of Detection (LoD), and the Limit of Quantitation (LoQ). These parameters form a fundamental sensitivity hierarchy, defining the capabilities and limitations of an analytical method [2] [14].

This guide provides a clear comparison of these concepts, supported by experimental data and standard protocols, to equip researchers and drug development professionals with the knowledge to properly validate analytical methods.

The Analytical Sensitivity Hierarchy: Core Definitions

The LoB, LoD, and LoQ represent consecutive levels in an assay's ability to discern and measure an analyte, with each requiring a greater analyte concentration than the last [2].

- Limit of Blank (LoB): The highest apparent analyte concentration expected to be found when replicates of a blank sample (containing no analyte) are tested. It is the threshold for false positives [2] [15].

- Limit of Detection (LoD): The lowest analyte concentration that can be reliably distinguished from the LoB. It confirms the analyte's presence but does not guarantee accurate quantification [2] [11].

- Limit of Quantitation (LoQ): The lowest concentration at which the analyte can not only be reliably detected but also quantified with acceptable precision and accuracy, as defined by pre-set goals for bias and imprecision [2] [8].

The following diagram illustrates the statistical relationship and progression between these three critical limits.

Comparative Analysis of LoB, LoD, and LoQ

The table below provides a detailed, side-by-side comparison of these three parameters, summarizing their purpose, statistical basis, and determination methods.

| Feature | Limit of Blank (LoB) | Limit of Detection (LoD) | Limit of Quantitation (LoQ) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Definition | Highest concentration expected from a blank sample [2] | Lowest concentration distinguished from LoB; detection is feasible [2] | Lowest concentration quantified with acceptable precision and accuracy [2] |

| Primary Purpose | Establish false-positive cutoff [16] | Confirm analyte presence [11] [17] | Report reliable numerical value [8] |

| Relation to Signal & Noise | Defines the background noise level | Signal is distinguishable from noise (S/N ≈ 3:1) [11] [4] | Signal is sufficient for quantification (S/N ≈ 10:1) [11] [4] |

| Key Question Answered | "Is the signal just background noise?" | "Is the analyte present?" | "How much analyte is there?" |

| Typical Statistical Confidence | 95th percentile of blank distribution (1 - α = 95%) [2] [16] | 95% probability of distinguishing from LoB (1 - β = 95%) [2] [16] | Predefined goals for bias and imprecision (e.g., CV ≤ 20%) [15] [8] |

| Common Calculation Methods | Non-parametric ranking of blanks: ( \text{LoB} = 95\text{th percentile of blank results} ) [16] | ( \text{LoD} = \text{LoB} + 1.645 \times \text{SD}_{\text{low concentration sample}} ) [2] | ( \text{LOQ} = 10 \times (\sigma / S) ) Where σ = SD and S = calibration curve slope [11] [8] |

| Relative Concentration | Lowest | Higher than LoB [2] | Highest; equal to or much higher than LoD [2] |

Experimental Protocols for Determination

Standardized protocols, such as those from the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) EP17-A2 guideline, provide robust methodologies for determining LoB, LoD, and LoQ [2] [16].

Protocol 1: Determining the Limit of Blank (LoB)

The LoB establishes the baseline noise of an assay and is determined by analyzing blank samples.

- Sample Type: Replicates of a blank sample containing no analyte, but in a representative sample matrix (e.g., wild-type plasma for a ctDNA assay) [16].

- Experimental Replicates: A minimum of N=30 blank replicates is recommended for a 95% confidence level [2] [16].

- Data Analysis (Non-Parametric):

- Measure all blank samples and record the apparent analyte concentrations.

- Sort the results in ascending order (Rank 1 to Rank N).

- Calculate the rank position: ( X = 0.5 + (N \times 0.95) ), where 0.95 represents the 95% confidence (1 - α).

- The LoB is the concentration value at the calculated rank X, determined by interpolation between the nearest ranked data points [16].

Protocol 2: Determining the Limit of Detection (LoD)

The LoD is calculated using the previously determined LoB and data from low-concentration analyte samples.

- Sample Type: Samples with a low, known concentration of the analyte (typically 1-5 times the LoB), prepared in the same matrix as the blank [2] [16].

- Experimental Replicates: Analyze a minimum of five independently prepared low-level samples, with at least six replicates each (total ≥ 30 measurements) [16].

- Data Analysis (Parametric):

- Calculate the global standard deviation (SD~L~) from all measurements of the low-level samples.

- Calculate the LoD using the formula: ( \text{LoD} = \text{LoB} + Cp \times \text{SD}L ).

- The multiplier ( C_p ) is a coefficient based on the 95th percentile of a normal distribution and the total number of measurements (L), typically close to 1.645 [16]. This ensures that the LoD concentration has a 95% probability of being distinguished from the LoB [2].

Protocol 3: Determining the Limit of Quantitation (LoQ)

The LoQ is the lowest concentration where quantification meets predefined performance criteria for precision and accuracy.

- Sample Type: Samples with analyte concentrations at or slightly above the estimated LoD [2].

- Experimental Replicates: Analyze multiple replicates (e.g., n=5) at different candidate concentrations near the LoD [8].

- Data Analysis (Performance-Based):

- For each candidate concentration, calculate the precision (Coefficient of Variation, %CV) and accuracy (relative error from the nominal concentration, %Bias).

- The LOQ is the lowest concentration where the method demonstrates acceptable performance, commonly defined as %CV ≤ 20% and %Bias within ±20% [8].

- The signal-to-noise ratio (S/N) method can also be used, where an S/N of 10:1 is generally accepted for LOQ [11] [4].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table outlines key materials and reagents required for conducting these validation experiments, particularly in immunoassay or chromatographic contexts.

| Research Reagent / Material | Critical Function in Validation |

|---|---|

| Blank Matrix | Provides the commutable sample background (e.g., buffer, wild-type serum, stripped plasma) without analyte to establish the LoB and baseline noise [16]. |

| Certified Reference Material | Provides an analyte of known purity and concentration for accurate preparation of low-level (LoD) and quantitation (LoQ) samples [2]. |

| Low-Level Quality Control (LL-QC) Samples | Representative samples spiked with analyte at concentrations 1-5x the LoB; used for LoD and LoQ determination [16]. |

| Calibrators | A series of standards used to construct a calibration curve, essential for the slope-based calculation of LOD/LOQ and for confirming linearity [11] [8]. |

A clear grasp of the analytical sensitivity hierarchy—where LoB < LoD ≤ LoQ—is fundamental for developing, validating, and interpreting methods in research and drug development. Properly distinguishing these limits prevents the misreporting of mere noise as detection, or unreliable low-concentration estimates as precise quantification. By applying the standardized experimental protocols and calculations outlined in this guide, scientists can ensure their methods are truly "fit-for-purpose," providing reliable data from the faintest trace to robust quantification.

The Limit of Quantitation (LOQ), also referred to as the Limit of Quantification, is a critical parameter in analytical method validation defined as the lowest concentration of an analyte that can be quantitatively determined with suitable precision and accuracy under stated experimental conditions [2]. Within the pharmaceutical industry, the determination of LOQ is governed by established regulatory guidelines, primarily the International Conference on Harmonisation (ICH) Q2(R1) guideline titled "Validation of Analytical Procedures: Text and Methodology" [3] [18]. This guideline, along with relevant pharmacopoeial standards, provides a framework for the validation of analytical procedures, ensuring that the methods used in drug development and quality control are reliable, accurate, and fit for their intended purpose [18].

The importance of LOQ is particularly pronounced in the context of quantifying impurities and degradation products, where accurate measurement at low levels is essential for demonstrating drug safety and quality [11]. For assays of drug substance or drug product (potency assays), the determination of LOQ is generally not required, as these typically operate at concentrations far above the quantitation limit [3] [11]. The focus of this guide is to objectively compare the primary methodologies for LOQ determination as outlined in ICH Q2(R1) and to provide the experimental protocols for their implementation.

Core Methodologies for LOQ Determination in ICH Q2(R1)

ICH Q2(R1) describes several approaches for determining the Limit of Quantitation. The guideline does not prescribe a single universal method but offers a selection of validated techniques, allowing analysts to choose the most appropriate one for their specific analytical procedure [3] [19]. The three principal approaches are based on visual evaluation, signal-to-noise ratio, and the standard deviation of the response and the slope of the calibration curve.

The table below provides a consolidated comparison of the core methodologies recognized by ICH Q2(R1) for determining the Limit of Quantitation.

Table 1: Comparison of LOQ Determination Methods per ICH Q2(R1)

| Methodology | Basis of Calculation | Typical LOQ Criterion | Common Applications | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Visual Evaluation | Analysis of samples with known concentrations of the analyte [3] | The minimum level at which the analyte can be reliably quantified [3] | Non-instrumental methods (e.g., titration) [11] | Intuitive; does not require specialized instrumentation [3] | Subjective; dependent on analyst interpretation [3] [20] |

| Signal-to-Noise Ratio | Comparison of measured signals from low analyte concentrations to background noise [3] | Signal-to-Noise ratio of 10:1 [3] [8] [11] | Instrumental methods with baseline noise (e.g., HPLC, chromatography) [3] [11] | Simple and rapid to implement; instrument software often provides direct measurement [3] | Requires a consistent and measurable baseline noise; can be arbitrary [20] |

| Standard Deviation & Slope | Based on the variability of the response and the sensitivity of the calibration curve [3] | LOQ = 10σ/S (where σ = standard deviation, S = slope) [3] [20] [11] | Quantitative assays, especially when a calibration curve is used [3] | Provides a statistical basis; considered more scientifically rigorous [20] | Requires a sufficient number of data points for reliable standard deviation estimation [3] |

Detailed Methodological Protocols

Protocol for Signal-to-Noise Ratio Method

The signal-to-noise (S/N) method is directly applicable to analytical techniques that exhibit a baseline background noise, such as chromatography [11].

- Instrumental Setup: Utilize the analytical instrument (e.g., HPLC with a relevant detector) under the standard operating conditions of the method [11].

- Blank Preparation: Run a blank sample, which is the sample matrix without the analyte [3].

- Low-Concentration Sample Preparation: Prepare and analyze a sample containing the analyte at a concentration known to be near the expected LOQ. Typically, five to seven concentrations are used with six or more determinations for each [3].

- Noise Measurement: Measure the background noise of the system from the blank injection. Noise is typically calculated by the instrument's data system over a representative section of the baseline [20].

- Signal Measurement: Measure the analyte signal (e.g., peak height) from the low-concentration sample.

- Ratio Calculation and LOQ Determination: Calculate the S/N ratio. The LOQ is defined as the concentration at which the S/N ratio is 10:1 [3] [11]. Non-linear modeling may be used to interpolate the exact concentration corresponding to this ratio from data at multiple levels [3].

Protocol for Standard Deviation and Slope Method

This approach is considered more statistically sound and is particularly suited for assays that utilize a calibration curve [20]. The standard deviation (σ) can be determined in two primary ways, as outlined in ICH Q2(R1).

Based on the Standard Deviation of the Blank:

- Procedure: Measure replicates (normally 10 or more) of a blank sample. The blank should be in the appropriate matrix but contain no analyte [3].

- Calculation: Calculate the standard deviation (SD) of these blank responses.

- LOQ Formula: LOQ = 10 × SD_blank / S, where S is the slope of the calibration curve [3]. This approach converts the variability in the response back to a concentration value using the sensitivity of the method (slope).

Based on the Calibration Curve:

- Procedure: Construct a calibration curve using samples with analyte concentrations in the range of the expected LOQ. The calibration curve should be generated using an appropriate number of concentration levels and replicates [3] [20].

- Standard Deviation (σ) Estimation: The standard deviation of the response can be estimated as:

- LOQ Formula: LOQ = 10 × σ / S, where σ is the selected standard deviation estimate and S is the slope of the calibration curve [3] [20]. An example calculation using linear regression output from software like Excel is provided in Section 3.1.

Figure 1: A workflow for determining the Limit of Quantitation (LOQ) using the primary methods outlined in ICH Q2(R1). The process begins with method selection, proceeds through specific calculation steps, and culminates in mandatory experimental validation.

Practical Application and Experimental Data

Worked Example: LOQ from Calibration Curve

A practical example of computing LOQ based on calibration curve data using a regression analysis, as implemented in software like Microsoft Excel, is illustrated below [20].

Table 2: Example Calibration Data for LOQ Calculation

| Concentration (ng/mL) | Signal (Area) |

|---|---|

| 1.0 | 2150 |

| 2.0 | 4200 |

| 3.0 | 6100 |

| 5.0 | 10500 |

| 7.0 | 14400 |

Linear Regression Output:

Calculation:

- LOQ = 10 × σ / S = 10 × 0.4328 / 1.9303 ≈ 2.2 ng/mL [20]

This calculated value should be considered an estimate and must be validated experimentally, as discussed in Section 3.3 [20].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The experimental determination of LOQ requires specific reagents and materials tailored to the analytical method. The table below lists key items and their functions in the context of LOQ determination.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for LOQ Experiments

| Item | Function in LOQ Determination | Specific Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| High-Purity Analyte | Serves as the reference standard for preparing known low-concentration samples for calibration and validation [21]. | Certified Reference Material (CRM) is ideal for accurate weighing and preparation. |

| Appropriate Blank Matrix | Represents the sample without the analyte; critical for measuring background noise and for the standard deviation of the blank method [3] [2]. | For bioanalysis, this could be blank plasma; for environmental, pesticide-free sediment/water [21]. |

| Calibration Standards | A series of samples with known analyte concentrations used to establish the relationship between signal and concentration (calibration curve) [8]. | Should cover the range from below to above the expected LOQ. |

| Quality Control (QC) Samples at LOQ | Independent samples prepared at the estimated LOQ concentration to validate the precision and accuracy of the method at that level [20]. | Typically prepared in multiple replicates (e.g., n=6). |

| Internal Standard (for certain methods) | Used in chromatographic assays to correct for variability in sample preparation and injection, improving precision at low levels [21]. | A compound that is structurally similar but analytically distinct from the analyte. |

Mandatory Experimental Validation

Regardless of the calculation method used, ICH Q2(R1) and scientific best practices require that the estimated LOQ be confirmed through experimental analysis [20]. This involves:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare a suitable number of samples (e.g., n=6) independently at the calculated LOQ concentration [20].

- Analysis and Evaluation: Analyze these samples using the fully validated analytical procedure. The results should demonstrate that the method can quantify the analyte at this level with acceptable precision and accuracy [20]. For bioanalytical methods, a precision of within 20% coefficient of variation (CV) and an accuracy of within 20% of the nominal concentration are typical acceptance criteria at the LOQ [8].

- Comparison with Other Methods: The calculated LOQ can be cross-verified using the other ICH methods. For instance, the signal from the validated LOQ concentration should consistently meet an S/N ratio of 10:1 [20].

The determination of the Limit of Quantitation is a foundational element of analytical method validation. ICH Q2(R1) provides a flexible yet rigorous framework through its multiple defined approaches. The choice between visual evaluation, signal-to-noise ratio, or standard deviation and slope methods depends on the nature of the analytical procedure, with the calibration curve method often being favored for its statistical robustness [20]. A critical best practice emphasized across guidelines and literature is that a calculated LOQ is merely an estimate until it is confirmed by rigorous experimental validation using samples prepared at that concentration. This ensures the method is truly "fit for purpose," providing reliable data to support drug development and ensure patient safety [2] [20].

Calculating and Applying LOQ: From S/N Ratio to Practical Implementation

This guide examines the direct signal-to-noise (S/N) ratio calculation method for determining the Limit of Detection (LOD) and Limit of Quantitation (LOQ) in chromatographic and spectroscopic techniques. The S/N approach, formally recognized in regulatory guidelines like ICH Q2(R1), provides a practical means to estimate the lowest analyte concentrations detectable and quantifiable by an analytical method. This objective comparison details the experimental protocols, performance data, and practical considerations of the S/N method against alternative approaches, providing supporting data for researchers and drug development professionals.

In analytical chemistry, characterizing a method's capabilities at low analyte concentrations is critical. The Limit of Detection (LOD) is the lowest concentration at which an analyte can be reliably detected, but not necessarily quantified, under stated experimental conditions. Conversely, the Limit of Quantitation (LOQ) is the lowest concentration that can be quantitatively determined with acceptable precision and accuracy [22] [2]. For chromatographic and spectroscopic techniques, the direct S/N ratio method is a widely adopted technique for determining these limits, leveraging the inherent baseline noise of the analytical system as a reference point. The International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) Q2(R1) guideline endorses this method alongside visual evaluation and statistical approaches based on the standard deviation of the response and the slope of the calibration curve [22]. The S/N method's primary strength lies in its direct utilization of the chromatogram or spectrum, offering an intuitive and experimentally accessible means of establishing method limits.

Core Principles of the S/N Calculation Method

The fundamental principle of this method is comparing the magnitude of the analyte's signal to the amplitude of the background noise. Baseline noise comprises all unwanted, statistically fluctuating signals superimposed on the measurement signal, limiting the method's sensitivity [4] [12]. The LOD and LOQ are defined by the ratios at which the analyte signal can be distinguished from this noise.

The ICH Q2(R1) guideline specifies standard S/N ratios for these limits. A signal-to-noise ratio between 2:1 and 3:1 is generally considered acceptable for estimating the LOD, while a typical ratio for the LOQ is 10:1 [22] [4]. It is important to note that an upcoming revision, ICH Q2(R2), is planned to require a S/N of 3:1 for the LOD, eliminating the 2:1 option [4]. In practice, many laboratories adopt more stringent, in-house criteria, often requiring a S/N from 3:1 to 10:1 for LOD and 10:1 to 20:1 for LOQ to ensure robustness with real-life samples and analytical conditions [4] [12].

A critical consideration is the method of noise measurement. Different approaches, such as measuring the peak-to-peak noise over a specified range, can yield different S/N values from the same data set, highlighting the need for a standardized protocol within a laboratory [22].

Experimental Protocol for S/N Determination

The following workflow and detailed protocol describe the standard procedure for determining LOD and LOQ via the direct S/N method in a liquid chromatography (LC) system, which is directly applicable to other chromatographic and spectroscopic techniques.

Diagram 1: S/N Determination Workflow. This diagram outlines the standard procedure for establishing LOD and LOQ via the S/N method, involving iterative analysis of standards until target ratios are met.

Detailed Step-by-Step Methodology

System Preparation and Blank Analysis: The chromatographic or spectroscopic system is equilibrated according to the validated method. A blank sample (the sample matrix without the analyte) is injected and run. The resulting chromatogram is used for noise measurement [4] [12].

Noise Measurement (

h): In the blank chromatogram, a peak-free region is selected, typically in a zone near the expected retention time of the analyte. The maximum amplitude of the background noise (h) is measured over an interval equivalent to at least 20 times the width at half the height of the analyte peak [13]. This value,h, represents the peak-to-peak noise.Low-Concentration Standard Analysis: A standard solution containing the analyte at a concentration expected to be near the LOD/LOQ is prepared and injected. The resulting chromatogram should show a discernible peak for the analyte.

Signal Measurement (

H): The height of the analyte peak (H) is measured from the maximum of the peak to the extrapolated baseline [13].S/N Ratio Calculation: The signal-to-noise ratio is calculated using the formula: ( S/N = \frac{H}{h} ) where ( H ) is the peak height of the analyte and ( h ) is the peak-to-peak noise [13].

Iterative Concentration Adjustment: Steps 3-5 are repeated with standard solutions of adjusted concentrations until the S/N ratio is approximately 3:1 for the LOD and 10:1 for the LOQ. The concentrations yielding these ratios are designated as the method's LOD and LOQ, respectively [4].

Validation: The determined limits should be subsequently validated by analyzing a suitable number of samples known to be near, or prepared at, the LOD and LOQ to confirm that they meet the required detection and quantitation criteria [13].

Performance Data and Comparison with Alternative Methods

The S/N method is one of several techniques for determining LOD and LOQ. The table below provides a objective comparison of its performance against other common approaches.

Table 1: Comparison of Methods for Determining LOD and LOQ

| Feature | Direct S/N Ratio | Standard Deviation & Slope | Visual Evaluation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Principle | Based on instrument response (signal height vs. baseline noise) [22] | Based on statistical parameters of the calibration curve (standard deviation of response and slope) [22] | Based on subjective assessment of chromatogram visibility [22] |

| Regulatory Status | Recognized by ICH Q2(R1) and pharmacopoeias (USP, EP) [22] [4] | Recognized by ICH Q2(R1) [22] | Recognized by ICH Q2(R1) [22] |

| LOD Criterion | S/N = 3:1 (2:1 to be discontinued per ICH Q2(R2)) [4] | Typically, 3.3 × (SD/Slope) [2] [13] | Analyst confidently identifies a peak [22] |

| LOQ Criterion | S/N = 10:1 [22] [4] | Typically, 10 × (SD/Slope) [2] [13] | Analyst confidently quantifies a peak [22] |

| Key Advantages | - Intuitive and simple to perform- Directly uses chromatographic data- Does not require extensive calibration | - Purely statistical and objective- Accounts for method precision and sensitivity- Does not rely on noise measurement | - Very fast and simple- Requires no calculations |

| Key Limitations | - Sensitive to noise measurement technique [22]- Can be arbitrary if protocol is not strictly defined | - Requires multiple replicate measurements- Relies on a linear calibration model at low concentrations | - Highly subjective and operator-dependent [22]- Lacks quantitative rigor |

The S/N method's primary advantage is its practical simplicity, but it is highly dependent on a consistent definition of noise. For instance, as demonstrated in one study, measuring the same chromatogram could yield S/N values of 1.2 or 0.9 using different noise definitions, and 2.4 or 1.8 when converted to pharmacopoeial methods, leading to potential inconsistency if not standardized [22]. In contrast, the statistical method based on standard deviation and slope, while more rigorous, is more labor-intensive as it requires numerous replicate measurements of a blank and a low-concentration sample to properly estimate standard deviation [2] [13].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful application of the S/N method requires high-quality materials and reagents to ensure accuracy and reproducibility. The following table details essential solutions and their functions.

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Materials for S/N-Based LOD/LOQ Studies

| Item | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| High-Purity Analytical Standards | Used to prepare low-concentration calibration standards with known, precise analyte concentrations. Purity is critical to avoid overestimating the signal from impurities [5]. |

| Appropriate Blank Matrix | A sample of the biological, environmental, or pharmaceutical matrix (e.g., plasma, mobile phase, formulation excipients) without the analyte. It is essential for accurately measuring the baseline noise and for preparing matrix-matched calibration standards. |

| Chromatography/Mass Spectrometry Grade Solvents | High-purity solvents are used for mobile phase preparation and standard dilution to minimize baseline noise and ghost peaks caused by solvent impurities [4]. |

| Data System (CDS) with Advanced Integration Algorithms | Software like Chromeleon CDS with Cobra or SmartPeaks algorithms can apply adaptive smoothing functions (e.g., Savitsky-Golay) to reduce baseline noise without losing valuable peak information, aiding in S/N calculation [4]. |

Critical Considerations for Method Optimization

Data Smoothing and Its Impact on S/N

A common practice to improve the S/N ratio is data smoothing using electronic filters (e.g., detector time constant) or mathematical algorithms (e.g., Gaussian convolution, Fourier transform, Savitsky-Golay) [4] [12]. While effective at reducing noise, over-smoothing can be detrimental. It can flatten and broaden small peaks near the baseline noise, potentially causing them to fall below the LOD criteria and go undetected [4]. A key best practice is to apply smoothing functions post-acquisition to preserve the original raw data, allowing for re-processing with different parameters if necessary [4].

Reporting and Real-World Variability

When reporting LOD and LOQ values derived from the S/N method, it is crucial to acknowledge the inherent uncertainty in measurements near the detection limit. Signals with an S/N of 3 can have experimental uncertainties approaching 33-50% [5]. Consequently, LOD values should be conservatively reported with only one significant digit to reflect this level of precision accurately [5]. Furthermore, real-world chromatographic conditions often necessitate stricter S/N criteria than the ICH minimums (e.g., 3:1 to 10:1 for LOD and 10:1 to 20:1 for LOQ) to ensure method robustness [4] [12].

The direct S/N ratio calculation provides a practical, widely accepted methodology for determining the Limit of Detection and Limit of Quantitation in chromatographic and spectroscopic techniques. Its integration into international regulatory guidelines underscores its utility. However, its effectiveness is contingent upon strict adherence to a standardized experimental protocol, particularly regarding noise measurement and data processing. While the S/N method offers an intuitive and direct approach, scientists must be aware of its limitations, including its sensitivity to measurement technique and the potential pitfalls of data smoothing. For methods requiring the highest level of objectivity, the S/N approach is best used to confirm results obtained through more rigorous statistical techniques, ensuring that analytical methods are truly fit-for-purpose in drug development and other critical research applications.

The Standard Deviation and Slope Approach (LOD = 3.3σ/S, LOQ = 10σ/S)

The determination of a method's limits is a fundamental requirement in analytical chemistry, providing crucial information about its capability to detect and quantify trace analytes. Among the various approaches outlined in the ICH Q2(R1) guideline, the method based on the standard deviation of the response and the slope of the calibration curve offers a statistically rigorous and scientifically satisfying alternative to more arbitrary techniques like visual evaluation or signal-to-noise ratio [20]. This approach defines the Limit of Detection (LOD) as the lowest concentration that can be detected but not necessarily quantified, while the Limit of Quantification (LOQ) is the lowest concentration that can be quantified with acceptable precision and accuracy [11]. The formulas are expressed as:

- LOD = 3.3σ / S

- LOQ = 10σ / S

Where σ is the standard deviation of the response and S is the slope of the calibration curve [11] [20].

The following table compares this method with other common techniques sanctioned by ICH guidelines.

Table 1: Comparison of ICH-Sanctioned Methods for Determining LOD and LOQ

| Method | Key Principle | Typical Applications | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard Deviation & Slope | Uses statistical parameters from a calibration curve in the low concentration range [23]. | Instrumental methods (e.g., HPLC, spectrophotometry) for impurities and degradation products [11]. | Statistically rigorous; does not require a baseline noise, making it suitable for techniques without a background signal [20] [3]. | Requires linearity in the low concentration range and variance homogeneity [23]. |

| Signal-to-Noise (S/N) | Compares the analyte signal from a sample with the background noise from a blank [11]. | Chromatographic and spectroscopic methods that exhibit baseline noise [4]. | Intuitively simple; directly uses chromatographic data. | Arbitrary; requires a measurable baseline noise; values can be influenced by data system filters and smoothing [20] [4]. |

| Visual Evaluation | Analysis of samples with known concentrations to establish the minimum level for reliable detection/quantification [11]. | Non-instrumental methods (e.g., inhibition tests) or titration; can be used by an instrument for particle detection [11] [3]. | Practical for non-instrumental or qualitative tests. | Subjective and highly dependent on the analyst or instrument settings [20]. |

A recent comparative study highlights that while the classical statistical strategy (including the standard deviation/slope approach) can provide a good estimate, graphical tools like the uncertainty profile—based on tolerance intervals and measurement uncertainty—can offer a more realistic assessment of a method's capabilities at low concentrations [19].

Detailed Experimental Protocol

This section outlines the step-by-step procedure for determining the LOD and LOQ using the standard deviation and slope approach, consistent with ICH Q2(R1) recommendations [23] [20].

Experimental Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for this methodology.

Step-by-Step Procedure

Preparation of Calibration Standards: Prepare a series of standard solutions at low concentrations in the range of the presumed LOD and LOQ. The highest concentration should not exceed 10 times the presumed LOD to ensure the calibration curve is centered appropriately for the determination [23]. Using a standard curve spanning the normal working range is not suitable, as it would lead to an overestimation of the limits [23].

Analysis of Standards: Analyze each calibration standard level with multiple replicates. The number of calibration curves and replicates can vary; a practical example uses 4 independent calibration lines with 5 concentration levels each [23].

Linear Regression and Data Analysis: Subject the analytical responses (e.g., peak areas) to linear regression analysis to obtain the calibration curve

y = mx + c, wheremis the slope (S). The critical parameterσ(the standard deviation of the response) can be determined in two primary ways, as specified by ICH [11] [23]:- Residual Standard Deviation (Recommended): This is the most straightforward method, often labeled as the standard error of the regression or the root mean squared error (RMSE) in statistical software [20]. It represents the standard deviation of the residuals (the differences between the observed and predicted values).

- Standard Deviation of the Y-Intercept: This method involves generating multiple independent calibration curves and calculating the standard deviation of their y-intercepts [11] [23]. While statistically valid, this approach is more labor-intensive.

Calculation of LOD and LOQ: Insert the obtained values for

σandSinto the formulas to calculate the estimated LOD and LOQ [20].Experimental Verification (Mandatory): The calculated LOD and LOQ values are estimates and must be experimentally confirmed. This is done by preparing and analyzing a suitable number of samples (e.g., n=6) at the calculated LOD and LOQ concentrations. The LOD samples should reliably demonstrate the presence of the analyte (e.g., with a S/N ≥ 3 for confirmation), while the LOQ samples should demonstrate acceptable precision (e.g., %RSD ≤ 15%) and accuracy [20]. If the results do not meet these criteria, the estimates must be revised.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The successful implementation of this methodology relies on several key materials and reagents to ensure accuracy and reproducibility.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Item | Function / Critical Role |

|---|---|

| High-Purity Analytic Reference Standard | Serves as the basis for preparing calibration standards. Its purity directly impacts the accuracy of the slope (S) of the calibration curve and the calculated limits. |

| Appropriate Solvent & Matrix | The solvent should completely dissolve the analyte. For bioanalytical methods, the calibration standards must be prepared in the same biological matrix (e.g., plasma) to account for matrix effects on the response and standard deviation [19]. |

| Chromatographic Mobile Phases & Columns | For HPLC-based methods, these are critical for achieving a stable baseline (low noise) and sufficient separation of the analyte from the solvent front and other components, which is essential for an accurate response at low concentrations [4]. |

| Statistical Software | Software capable of performing linear regression and providing the residual standard deviation (standard error) and slope is indispensable. Common tools include Microsoft Excel's data analysis pack, specialized CDS software (e.g., Chromeleon), or other statistical packages [23] [20]. |

Data Presentation and Analysis

To illustrate the calculation process, consider the following constructed data set from an RP-HPLC method, where the LOQ was previously estimated to be 6 μg/mL, suggesting a LOD near 1.8 μg/mL [23].

Table 3: Example Calibration Data and LOD/LOQ Calculation

| Experiment | Slope (S) | Residual Standard Deviation (σ) | Calculated LOD (μg/mL) | Calculated LOQ (μg/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Line 1 | 15878 | 3443 | 0.72 | 2.17 |

| Line 2 | 15814 | 3333 | 0.70 | 2.11 |

| Line 3 | 16562 | 1672 | 0.33 | 1.01 |

| Line 4 | 15844 | 3436 | 0.72 | 2.17 |

| Mean (Excl. Line 3) | 15845 | 3404 | 0.71 | 2.15 |

Note: Data adapted from a practical example [23]. The results from Line 3 are an outlier, highlighting the importance of using multiple independent calibration lines for a robust estimate.

This example demonstrates that results can vary depending on the specific calibration curve used, reinforcing the need for replication. The final LOD and LOQ would be based on the mean or worst-case result and then verified experimentally. It is also crucial to note that different evaluation techniques (residual SD vs. SD of the y-intercept) can yield different results, and the choice should be scientifically justified [23].

The Limit of Quantitation (LOQ) is a critical parameter in analytical method validation, representing the lowest concentration of an analyte that can be quantitatively determined with suitable precision and accuracy under stated experimental conditions [11]. For researchers and drug development professionals, establishing a reliable LOQ is essential for detecting and quantifying low-level impurities, degradation products, or biomarkers, particularly in pharmaceutical analysis and bioanalytical methods [4] [19]. The International Conference on Harmonisation (ICH) Q2(R1) guideline defines typical signal-to-noise ratios for LOQ determination and provides a framework for validation, though interpretation and application of these guidelines vary significantly in practice [4] [20].

This guide compares the predominant approaches for LOQ determination in HPLC, focusing on their practical implementation, relative merits, and limitations. We provide a structured comparison of methodologies, detailed experimental protocols, and a practical example to illustrate the calculation processes, enabling scientists to make informed decisions about LOQ determination in their analytical workflows.

Several methodologies exist for determining LOQ, each with distinct procedural requirements, advantages, and limitations. The ICH Q2(R1) guideline recognizes three primary approaches: visual evaluation, signal-to-noise ratio, and the standard deviation of the response and slope of the calibration curve [20] [11]. Recent research has also introduced more advanced graphical validation tools like uncertainty profiles [19].

Table 1: Comparison of Major LOQ Determination Methods

| Method | Basis of Determination | Typical LOQ Criterion | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Signal-to-Noise (S/N) [4] [20] | Ratio of analyte signal to baseline noise | S/N ≥ 10:1 | Simple, intuitive, instrument-independent | Susceptible to subjective measurement, high variability between instruments and integrators [24] |

| Calibration Curve [20] [11] | Standard error of regression and slope | LOQ = 10σ/S | Statistical basis, uses entire calibration data | Requires samples in relevant concentration range, can provide underestimated values [19] |

| Visual Evaluation [25] [11] | Visual assessment of chromatograms | Lowest concentration with detectable and measurable peak | Practical, accounts for real chromatographic context | Subjective, depends on analyst experience |

| Uncertainty Profile [19] | Tolerance intervals and measurement uncertainty | Intersection of uncertainty and acceptability limits | Comprehensive uncertainty assessment, realistic values | Computationally complex, requires specialized statistical knowledge |

Comparative studies consistently demonstrate that these approaches yield different LOQ values for the same analytical method. One investigation found the S/N method provided the lowest LOQ values, while the standard deviation of response and slope method yielded the highest values [26]. Another study on aflatoxin analysis in hazelnuts concluded that visual evaluation provided more realistic LOD and LOQ values compared to other approaches [25].

Experimental Protocols for LOQ Determination

Signal-to-Noise Method Protocol

The signal-to-noise method is widely applied in chromatographic systems exhibiting baseline noise [4] [11].

- Instrumentation: HPLC system with UV or DAD detector; Data acquisition system.

- Preparation: Prepare analyte solutions at concentrations expected to yield signals near the anticipated LOQ. A blank solution (without analyte) should also be prepared using the same matrix.

- Chromatographic Analysis: Inject the blank solution and low-concentration analyte solutions using validated chromatographic conditions.

- Noise Measurement: Select a peak-free region of the chromatogram, typically 1 minute in width, either immediately before or after the analyte peak. Avoid regions with significant baseline drift or artifacts [24].

- Signal Measurement: Measure the height of the analyte peak from the baseline.

- Calculation: Compute the S/N ratio by dividing the analyte peak height by the peak-to-peak noise in the selected baseline region. The LOQ is the lowest concentration that consistently yields S/N ≥ 10:1 across replicate injections [4] [20].

Calibration Curve Method Protocol

This statistical approach is generally preferred for its mathematical rigor [20] [24].

- Calibration Standards: Prepare a minimum of 5-6 standard solutions spanning the expected range of the LOQ. The range should include concentrations both below and above the anticipated LOQ.

- Analysis: Inject each standard solution in replicate (typically n=3-5) using the proposed chromatographic method.

- Linear Regression: Plot peak response (e.g., area) against concentration and perform linear regression analysis to obtain the slope (S) and standard error (σ) of the regression.

- Calculation: Apply the formula LOQ = 10σ/S to calculate the estimated quantitation limit [20].

- Verification: Prepare and analyze a minimum of 6 samples at the calculated LOQ concentration to confirm that the method demonstrates acceptable precision (typically ≤ 15% RSD) and accuracy (typically ±15% of the true value) at this level [20].

Practical HPLC Example: LOQ Determination for Carbamazepine

To illustrate the calibration curve method, we utilize published data comparing LOD and LOQ approaches for carbamazepine analysis using HPLC-UV [26].

Table 2: Example Calibration Data for Carbamazepine LOQ Determination

| Concentration (ng/mL) | Peak Area (mAU*s) |

|---|---|

| 1.0 | 1.95 |

| 2.0 | 3.89 |

| 5.0 | 9.80 |

| 10.0 | 19.52 |

| 20.0 | 39.15 |

| 50.0 | 97.85 |

Linear Regression Analysis:

- Slope (S): 1.9303

- Standard Error (σ): 0.4328

- Calculation: LOQ = 10 × 0.4328 / 1.9303 = 2.24 ng/mL

Based on this calculation, the LOQ for carbamazepine using this method would be approximately 2.24 ng/mL, which would likely be rounded to 2.5 ng/mL for practical application [20].

Experimental Verification: To validate this LOQ, six replicate samples at 2.5 ng/mL would be prepared and analyzed to confirm that the method yields a signal-to-noise ratio ≥ 10:1 and demonstrates precision with RSD ≤ 15% [20].

Visualization of Method Selection and Workflow

The following decision pathway outlines the systematic process for selecting and implementing the appropriate LOQ determination method:

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following reagents and materials are fundamental for conducting LOQ determination studies in HPLC:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for HPLC LOQ Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Purpose | Considerations for LOQ Determination |

|---|---|---|

| HPLC-Grade Solvents | Mobile phase components | Low UV cutoff, high purity to minimize baseline noise and ghost peaks [4] |

| Analytical Reference Standards | Calibration and quantification | Certified purity and stability for preparing accurate stock solutions [20] |

| Matrix-Matched Blanks | Background signal assessment | Placebo or biological matrix without analyte for noise measurement [24] |

| Internal Standards | Normalization of analytical response | Especially valuable in bioanalytical methods to improve precision at low concentrations [19] |

| HPLC Columns | Analytical separation | Appropriate selectivity and efficiency for resolving analyte from interferences [27] |

This guide has provided a comprehensive comparison of LOQ determination methods with a practical example illustrating the calibration curve approach. While the signal-to-noise method offers simplicity, the calibration curve approach provides greater statistical rigor [20] [24]. Recent methodologies such as uncertainty profiles represent promising developments for more realistic LOQ assessment [19].

The optimal approach depends on the specific application, regulatory requirements, and available resources. Regardless of the method selected, experimental verification through replicate analysis at the determined LOQ remains essential for demonstrating method suitability [20]. This systematic approach to LOQ determination ensures reliable quantification at the lowest concentrations, supporting robust analytical method validation in pharmaceutical research and development.

The limit of quantitation (LOQ) is a fundamental parameter in analytical science, defining the lowest concentration of an analyte that can be measured with acceptable accuracy and precision. A key determinant of the LOQ is the signal-to-noise ratio (S/N), which quantifies how clearly an analyte's signal can be distinguished from background variability [11]. While the relationship between S/N and LOQ is well-established in high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), the principles of S/N optimization are universally critical across a diverse array of analytical platforms.

This guide explores how S/N principles are applied to enhance the LOQ in techniques including Lateral Flow Immunoassays (LFIA) and X-Ray Fluorescence (XRF), providing a comparative framework for researchers and scientists in drug development and beyond.

S/N and LOQ: Core Concepts and Definitions

The Limit of Quantitation (LOQ) is formally defined as the lowest analyte concentration that can be quantitatively detected with stated accuracy and precision [8]. For chromatographic methods, a S/N ratio of 10:1 is a generally accepted criterion for determining the LOQ [11]. This ensures the signal is sufficiently strong above the background noise for reliable quantification.

It is crucial to distinguish the LOQ from the Limit of Detection (LOD), which is the lowest concentration that can be reliably detected—but not necessarily quantified—and is often based on a S/N ratio of 3:1 [11]. The LOQ, being a quantitative benchmark, is always a higher, more stringent concentration than the LOD [2].

Comparative Performance Data: S/N and LOQ Across Platforms

The following table summarizes the typical S/N requirements and reported LOQ performance for various analytical techniques, illustrating how S/N optimization directly enhances quantitative capabilities.

Table 1: Comparison of S/N Principles and LOQ Performance Across Analytical Platforms

| Analytical Platform | Typical S/N for LOQ | Key S/N Optimization Strategies | Reported LOQ Performance / Impact on Sensitivity |

|---|---|---|---|

| HPLC | 10:1 [11] | Use of high-performance detectors, optimized mobile phases, and column chemistry [28]. | Achievable impurity assays ~0.01%; highly precise and robust for quality control [28]. |

| Lateral Flow Immunoassay (LFIA) | Not specified, but higher S/N is the goal. | Signal Amplification: Using larger gold nanoparticles (AuNPs), AuNP clusters, novel labels (MEF, SERS) [29] [30].Noise Reduction: Using transparent membranes with light-absorbing backing cards to minimize background reflection [30]. | Plasmonic scattering LFIA showed 2600-4400x higher detection limit vs. commercial LFIAs in influenza A assays [30]. |

| X-Ray Fluorescence (XRF) | Not specified, but S/N is critical for LOD/LOQ. | Hardware: Optimizing X-ray tube power, using high-performance detectors, applying material-specific filters [31] [32].Sample Prep: Homogenization, particle size reduction, controlling sample thickness [32]. | With optimized Cu filter, LOQ for Chromium in leachate of 0.32 mg/L was achieved, well below the 2.5 mg/L regulatory limit [31]. |

| General Clinical/Bioanalytical | Based on precision (e.g., CV ≤20%) [8]. | Using characterized antibodies with fast association rates, buffer optimization, and replicate testing of low-concentration samples [8] [2]. | The LLOQ is the lowest calibration standard where the analyte response is at least five times that of the blank [8]. |

Experimental Protocols for S/N and LOQ Determination

Protocol for Determining LOQ via S/N in Instrumental Methods (e.g., HPLC)

This standard approach is applicable to methods that exhibit a baseline noise.

Procedure:

- Prepare and analyze a sample containing the analyte at a very low concentration.

- Measure the amplitude of the analyte signal.

- In a nearby section of the chromatogram or baseline, measure the peak-to-peak noise amplitude.

- Calculate the S/N ratio by dividing the analyte signal by the noise amplitude.

- The LOQ is the concentration of analyte that yields a S/N ratio of 10:1 [11].

Alternative Calculation-Based Method: The LOQ can also be calculated using the formula: LOQ = 10 × σ / S, where 'σ' is the standard deviation of the response (e.g., from multiple blank measurements or the residual standard deviation of a calibration curve) and 'S' is the slope of the analytical calibration curve [8] [11].

Protocol for Enhancing S/N in Lateral Flow Immunoassays (LFIA)

This protocol is based on recent research for constructing a high-sensitivity, plasmonic scattering-utilizing LFIA [30].

- Procedure:

- Membrane Transparency: To minimize background reflection from the nitrocellulose membrane, impregnate it with a medium whose refractive index (e.g., specific oils or solvents) closely matches that of the membrane itself. This dramatically reduces diffuse light scattering, turning the membrane transparent [30].

- Backing Card Selection: Replace the conventional white backing card with a black, light-absorbing card. This further reduces the background signal against which the test line is read [30].

- Optical Label Selection: Use gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) approximately 100 nm in diameter. According to Mie theory, 100 nm AuNPs exhibit a strong scattering signal, which becomes the dominant, easily visible signal against the new dark background [30].

- Result Readout: The test lines will appear as orange scattering lines on a black background, enabling naked-eye detection with significantly higher sensitivity compared to conventional absorption-based LFIAs [30].

Protocol for Optimizing S/N in X-Ray Fluorescence (XRF) Spectroscopy

This protocol outlines steps to improve the S/N for detecting specific elements, such as Chromium [31] [32].

- Procedure:

- Filter Optimization: To reduce background scattering in the energy range of interest, place a filter between the X-ray source and the sample. For Chromium, simulations and experiments indicate a Copper filter with a thickness between 100 μm and 140 μm is optimal [31].

- Instrument Parameter Tuning: Adjust the X-ray tube power to a level that provides a strong fluorescence signal without excessively increasing the general background noise [32].

- Sample Preparation: Homogenize the sample and, if possible, reduce and standardize particle size to minimize scattering and other matrix effects that contribute to noise [32].

- Detector Selection: Use a detector with high count-rate capability and energy resolution to better distinguish the characteristic fluorescence signal from the background [32].

- LOQ Verification: Analyze standards with known low concentrations of the analyte to verify that the achieved LOQ, derived from the optimized S/N, meets the required sensitivity thresholds [31].

Visualizing the Pathway to an Optimized LOQ

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship between fundamental concepts, optimization strategies, and the final goal of achieving a lower LOQ across different analytical platforms.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for S/N and LOQ Optimization