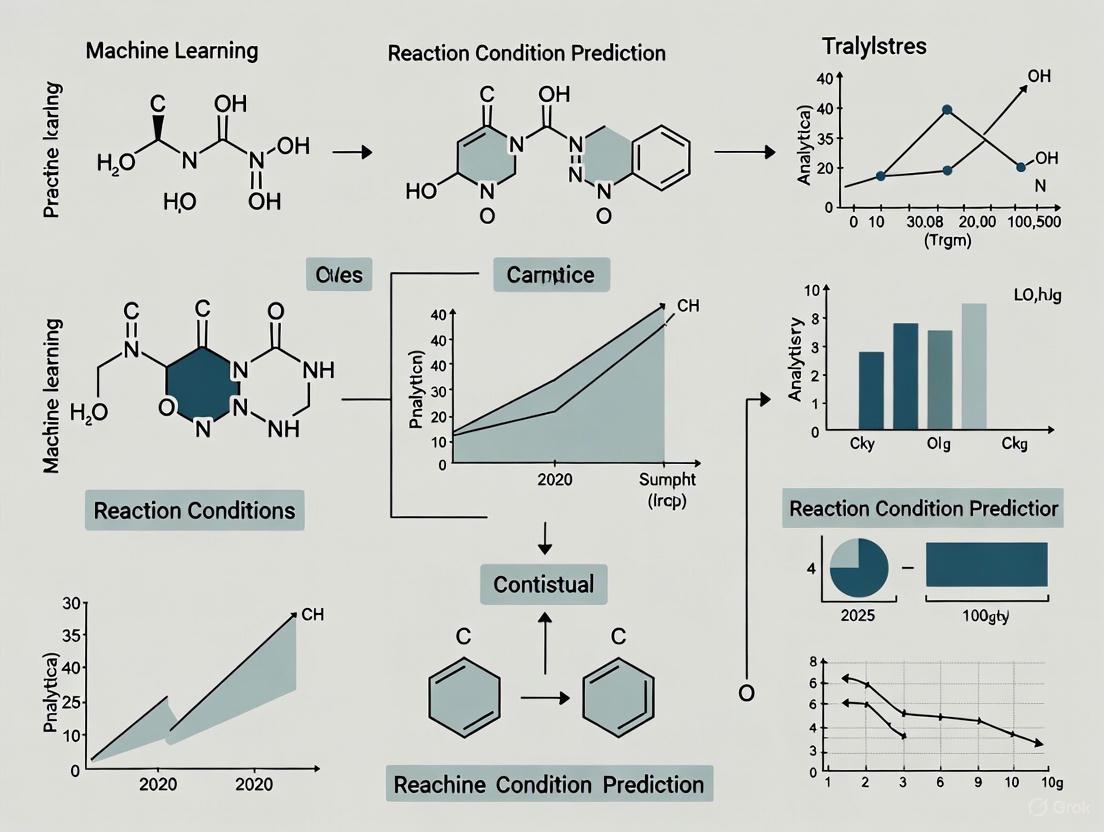

Machine Learning for Reaction Condition Prediction: Accelerating Drug Discovery and Synthetic Chemistry

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the transformative role of machine learning (ML) in predicting and optimizing chemical reaction conditions, a critical challenge in synthetic chemistry and pharmaceutical development.

Machine Learning for Reaction Condition Prediction: Accelerating Drug Discovery and Synthetic Chemistry

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the transformative role of machine learning (ML) in predicting and optimizing chemical reaction conditions, a critical challenge in synthetic chemistry and pharmaceutical development. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles, from the historical reliance on heuristic methods to the core challenges of data scarcity and molecular representation. The review delves into key ML methodologies, including Bayesian optimization, graph neural networks, and high-throughput experimentation, highlighting their application in real-world drug discovery pipelines. It further addresses persistent bottlenecks and optimization strategies, evaluates model performance and validation benchmarks, and concludes with future directions, underscoring ML's potential to reduce development timelines, lower costs, and enable novel discoveries in biomedical research.

The Fundamentals of Reaction Condition Prediction: From Heuristics to Data-Driven AI

In the development of pharmaceutical chemicals and fine chemicals, optimizing reaction conditions is a critical strategy for improving product yields, reducing waste and cost, extending product life cycles, and accelerating the time-to-market for new chemical entities [1]. This process involves carefully balancing numerous interdependent variables, including the concentration of reactants, reaction temperature, physical state and surface area of reactants, and the nature of the solvent [1]. The complexity of this optimization challenge grows exponentially with the number of variables, creating a high-dimensional search space that traditional experimental approaches struggle to navigate efficiently.

The emergence of machine learning (ML) and automated high-throughput experimentation (HTE) has begun to transform this landscape. ML-guided strategies now leverage both global models that exploit information from comprehensive databases to suggest general reaction conditions, and local models that fine-tune specific parameters for given reaction families to improve yield and selectivity [2]. These approaches are particularly valuable in pharmaceutical process development, where reactions must satisfy rigorous economic, environmental, health, and safety considerations, often necessitating the use of lower-cost, earth-abundant, and greener alternatives [3].

The High Stakes of Reaction Optimization

Impact on Efficiency and Sustainability

Reaction condition optimization directly influences three critical aspects of chemical manufacturing:

Process Efficiency: Optimal conditions maximize reaction speed and output, directly reducing development timelines and manufacturing costs. In one pharmaceutical case study, an ML framework identified improved process conditions at scale in just 4 weeks compared to a previous 6-month development campaign [3].

Resource Utilization: Precise optimization reduces consumption of expensive catalysts, ligands, and solvents while minimizing material waste throughout development and production.

Environmental Footprint: By identifying conditions that use safer solvents, reduce energy consumption through lower temperature requirements, and generate less hazardous waste, optimization directly supports green chemistry principles [4].

Consequences of Suboptimal Conditions

The impact of poorly optimized reactions extends beyond simple yield reduction:

Economic Losses: Pharmaceutical development teams report that many reactions prove unsuccessful, creating significant bottlenecks in drug discovery pipelines [3].

Scalability Failures: Conditions that work at laboratory scale often fail to translate to production environments, requiring costly re-optimization.

Product Quality Issues: Suboptimal conditions can lead to increased impurities, altered crystal forms, or undesirable physical properties that affect drug efficacy and safety.

Table 1: Economic and Operational Impact of Reaction Optimization in Pharma

| Aspect | Traditional Approach | ML-Optimized Approach | Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Development Timeline | 6+ months | 4 weeks [3] | 85% reduction |

| Experimental Efficiency | One-factor-at-a-time | Highly parallel (96-well HTE) [3] | 20x increase in throughput |

| Material Consumption | High (gram scale) | Low (microtiter plate scale) [3] | 95% reduction in waste |

| Success Rate | Limited by chemical intuition | Data-driven Bayesian optimization [3] | Significant improvement in identifying viable conditions |

Technical Challenges in Reaction Optimization

Fundamental Chemical Complexity

The core challenge in reaction optimization stems from the complex, multi-variable nature of chemical systems where subtle changes to individual parameters can dramatically alter outcomes:

Temperature Dependence: Reaction rates typically increase with temperature due to increased particle kinetic energy and collision frequency [1]. However, temperature can also fundamentally alter reaction pathways, as demonstrated by ethanol producing diethyl ether at 100°C but ethylene at 180°C under otherwise similar conditions [1].

Solvent Effects: The nature of the solvent profoundly impacts reaction rates through solvation effects, polarity, and hydrogen bonding potential. For instance, the reaction between sodium acetate and methyl iodide proceeds 10 million times faster in dimethylformamide (DMF) than in methanol due to hydrogen bonding differences [1].

Physical State Considerations: In heterogeneous systems, reactions occur only at phase interfaces, dramatically reducing collision frequency compared to homogeneous systems [1]. optimizing surface area through micro-droplet formation or particle size reduction becomes critical.

Data-Related Challenges for ML Approaches

Machine learning applications in reaction optimization face several significant hurdles:

Data Quality and Sparsity: Existing approaches often struggle with limited, noisy, or inconsistent reaction data, sometimes failing to surpass simple literature-derived popularity baselines [5].

Representation Limitations: Choosing appropriate representations for chemical reactions and conditions significantly impacts model performance. The Condensed Graph of Reaction representation has shown promise in enhancing predictive power beyond baseline methods [5].

High-Dimensional Search Spaces: Real-world optimization must navigate complex spaces with 10+ parameters including catalysts, ligands, solvents, concentrations, and temperatures, creating combinatorial explosions that challenge traditional approaches [4] [3].

Machine Learning Solutions Framework

Advanced ML Methodologies for Reaction Optimization

Recent advances in machine learning have produced several powerful frameworks specifically designed to address chemical optimization challenges:

Minerva ML Framework: A scalable machine learning framework for highly parallel multi-objective reaction optimization with automated high-throughput experimentation. This approach demonstrates robust performance with experimental data-derived benchmarks, efficiently handling large parallel batches, high-dimensional search spaces, reaction noise, and batch constraints present in real-world laboratories [3].

Bayesian Optimization with Gaussian Processes: This approach uses uncertainty-guided ML to balance exploration and exploitation of reaction spaces, identifying optimal reaction conditions using only small experimental subsets. Bayesian optimization has shown promising results experimentally, outperforming human experts in simulations [3].

Algorithmic Process Optimization (APO): A proprietary machine learning platform developed by Sunthetics in collaboration with Merck that integrates Bayesian Optimization and active learning into pharmaceutical process development. APO handles numeric, discrete, and mixed-integer problems with 11+ input parameters, replacing traditional Design of Experiments with a more efficient alternative [4].

Table 2: Machine Learning Approaches for Reaction Optimization

| ML Method | Key Features | Applications | Performance Benefits |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bayesian Optimization with Gaussian Processes | Balances exploration vs exploitation, handles uncertainty [3] | Ni-catalyzed Suzuki reactions, Buchwald-Hartwig couplings [3] | Identifies optimal conditions in small experimental subsets; outperforms human experts in simulations [3] |

| Multi-objective Acquisition Functions (q-NEHVI, q-NParEgo, TS-HVI) | Scalable parallel optimization of multiple objectives [3] | Pharmaceutical process development with yield, selectivity, cost targets [3] | Enables efficient optimization of competing objectives in large batch sizes (24-96 wells) [3] |

| Reaction-Conditioned Generative Models (CatDRX) | Generates novel catalyst designs conditioned on reaction components [6] | Catalyst discovery and design across reaction classes [6] | Creates new catalyst candidates beyond existing libraries; competitive yield prediction performance [6] |

| High-Throughput Experimentation Integration | Combines ML with automated robotic screening platforms [3] | Parallel optimization campaigns in 96-well formats [3] | Explores 88,000+ condition combinations efficiently; reduces experimental burden [3] |

Integrated Experimental-ML Workflows

Successful implementation of ML for reaction optimization requires tight integration between computational and experimental components:

Troubleshooting Guide: Common ML-Optimization Challenges

Data Quality and Model Performance Issues

Q: Our ML models for reaction condition prediction are failing to surpass simple literature-derived popularity baselines. What could be causing this poor performance?

A: This common challenge typically stems from several root causes:

Insufficient or Noisy Training Data: Ensure your dataset has adequate coverage of the chemical space of interest. Consider using data augmentation techniques or transfer learning from larger reaction databases like the Open Reaction Database (ORD) [6].

Suboptimal Reaction Representation: Evaluate alternative reaction representations beyond simple fingerprints. The Condensed Graph of Reaction representation has demonstrated enhanced predictive power for challenging transformations like heteroaromatic Suzuki–Miyaura reactions [5].

Inappropriate Model Complexity: Balance model complexity with available data. Overly complex models on limited data often underperform simple baselines, while overly simple models cannot capture complex chemical relationships.

Q: How can we effectively optimize multiple competing objectives like yield, selectivity, and cost simultaneously?

A: Multi-objective optimization requires specialized approaches:

Implement Scalable Acquisition Functions: Use multi-objective acquisition functions like q-NParEgo, Thompson sampling with hypervolume improvement (TS-HVI), or q-Noisy Expected Hypervolume Improvement (q-NEHVI) that can handle large batch sizes and multiple objectives efficiently [3].

Define Pareto Frontiers: Frame the problem as identifying Pareto-optimal conditions where no single objective can be improved without worsening another. The hypervolume metric can quantitatively measure multi-objective optimization performance [3].

Weighted Objective Formulations: For simpler cases, combine multiple objectives into a single weighted objective function, adjusting weights to reflect changing priorities across development stages.

Experimental Design and Implementation Challenges

Q: Our high-throughput experimentation campaigns are generating thousands of data points, but we're still missing optimal conditions. How can we improve our experimental design?

A: This indicates inefficient search space exploration:

Replace Grid Designs with Adaptive ML-Guided Designs: Traditional fractional factorial screening plates with grid-like structures explore only limited, fixed combinations. Instead, use ML-guided batch selection that adapts based on previous results [3].

Balance Exploration and Exploitation: Ensure your acquisition function properly balances exploring uncertain regions of the search space while exploiting known promising areas. Adjust this balance as the optimization progresses.

Incorporate Chemical Knowledge Constraints: Use algorithmic filtering to exclude impractical conditions (e.g., temperatures exceeding solvent boiling points, unsafe reagent combinations) while allowing broader exploration of plausible space [3].

Q: We need to optimize reactions with both categorical variables (solvents, catalysts) and continuous parameters (temperature, concentration). How can ML handle this mixed parameter space effectively?

A: Mixed parameter spaces require special consideration:

Represent Categorical Variables Appropriately: Convert molecular entities (solvents, catalysts) into numerical descriptors using learned representations rather than one-hot encoding. Reaction-conditioned models that learn joint representations of catalysts and reaction components have shown promise here [6].

Staged Optimization Approach: First conduct broad exploration of categorical variables that dramatically impact outcomes, then refine continuous parameters. Categorical variables often create distinct optima that require thorough initial exploration [3].

Hybrid Optimization Strategies: Combine global search across categorical variables with local refinement of continuous parameters using trust region methods or multi-fidelity approaches.

Research Reagent Solutions for ML-Optimization Experiments

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for ML-Guided Reaction Optimization

| Reagent/Resource | Function in Optimization | Application Notes | ML Integration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Taq DNA Polymerase [7] | Enzyme for PCR amplification in biological systems | Requires Mg²⁺ cofactor (1.5-5.0 mM); optimal concentration 0.5-2.5 units/50μL reaction [7] | Template for biochemically-inspired optimization protocols |

| Dimethylformamide (DMF) [1] | Polar aprotic solvent for enhanced reaction rates | Enables 10⁷-fold rate increase vs. methanol for nucleophilic substitutions [1] | Benchmark for solvent effect prediction in ML models |

| Bayesian Optimization Software (Minerva) [3] | ML framework for parallel reaction optimization | Handles 530-dimensional spaces; compatible with 96-well HTE formats [3] | Core algorithm for experimental design and optimization |

| Gaussian Process Regressors [3] | Predicts reaction outcomes with uncertainty estimates | Key component for balancing exploration/exploitation in Bayesian optimization [3] | Uncertainty quantification for experimental selection |

| Condensed Graph of Reaction Representations [5] | Alternative reaction representation for ML models | Enhances predictive power beyond popularity baselines for challenging reactions [5] | Improved feature representation for reaction condition prediction |

| High-Throughput Experimentation Robotics [3] | Automated execution of parallel reaction screening | Enables 96-well plate campaigns exploring 88,000+ condition combinations [3] | Physical implementation platform for ML-designed experiments |

| Open Reaction Database (ORD) [6] | Broad reaction database for model pre-training | Provides diverse reaction data for transfer learning to specific optimization tasks [6] | Knowledge base for improving model generalization |

FAQ: Practical Implementation Questions

Q: How do we determine the appropriate batch size for our Bayesian optimization campaigns?

A: Optimal batch size depends on your experimental capabilities and optimization goals:

Small Batches (8-16): Suitable for manual experimentation or when reaction cost is very high. Allows more frequent model updates but may require more iterations.

Medium Batches (24-48): Balanced approach for most pharmaceutical optimization campaigns. Compatible with many HTE platforms.

Large Batches (96+): Maximum efficiency for well-equipped HTE labs. Enables broader exploration per iteration but requires sophisticated acquisition functions like q-NParEgo or TS-HVI that scale efficiently to large batches [3].

Q: What validation is required before implementing ML-suggested conditions at production scale?

A: Always employ a staged validation approach:

Laboratory Validation: Confirm ML predictions at laboratory scale (1-10x HTE scale) using traditional analytical methods.

Mini-plant Trials: Conduct small-scale continuous or batch trials (100-1000x scale) to identify any scale-dependent effects.

Computational Validation: For catalyst design applications, use computational chemistry tools (DFT, molecular dynamics) to validate proposed catalysts, especially for novel structures generated by ML models [6].

Q: How can we assess whether our ML optimization campaign is working effectively?

A: Monitor these key performance indicators:

Hypervolume Progress: Track the hypervolume metric throughout the campaign to measure multi-objective optimization performance [3].

Condition Diversity: Ensure each batch explores diverse regions of parameter space rather than converging too quickly.

Improvement Rate: Monitor the rate of improvement in primary objectives. Successful campaigns typically show rapid early improvement followed by refinement.

Comparative Performance: Benchmark against traditional approaches (human expert designs, grid searches) using historical or parallel experimental data.

The optimization of reaction conditions represents a critical challenge with significant implications for pharmaceutical and fine chemical development. Traditional approaches, limited by human intuition and one-factor-at-a-time experimentation, struggle to navigate the high-dimensional, multi-objective optimization spaces characteristic of complex chemical systems. Machine learning frameworks, particularly when integrated with automated high-throughput experimentation, offer a powerful alternative that can dramatically accelerate development timelines, improve process efficiency, and enable more sustainable manufacturing. As these technologies continue to mature, their ability to handle real-world complexities—from data sparsity and noise to multi-objective optimization and novel chemical discovery—will further transform how the chemical industry approaches one of its most fundamental challenges.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What are the most common causes of failed experiments when relying on heuristic rules? The primary causes are the limited scope of human expertise and ignoring parameter interactions. Heuristic rules are often derived from a chemist's individual experience with a limited set of reactions and may not generalize well to new, unfamiliar substrates. Furthermore, the traditional "one factor at a time" (OFAT) optimization approach fails to account for complex interactions between variables like catalysts, solvents, and temperature, often leading to suboptimal or failed conditions [8].

Q2: My reaction yield is low despite following a literature procedure. How can I troubleshoot this? This is a common issue, as literature databases often contain a bias toward successful results and may omit failed experiments. First, verify the purity of your starting materials. Then, systematically explore condition combinations rather than single parameters. Key factors to re-investigate include [8]:

- Catalyst and ligand system: Small structural changes in the substrate can require different catalysts.

- Solvent effects: The polarity and coordinating ability of the solvent can drastically alter outcomes.

- Temperature and concentration: These are often highly specific to the exact substrates used.

Q3: How can I efficiently find a suitable starting point for a reaction with no direct precedent? The standard approach is the "nearest-neighbor" method, where you identify the most structurally similar reaction in the literature and adopt its conditions [9]. However, this method is rigid and may not work if the nearest neighbor's data is incomplete. It also does not account for condition compatibility, such as whether a reaction can proceed in a different, perhaps more desirable, solvent [9].

Q4: What are the major limitations of using large commercial reaction databases? While databases like Reaxys are invaluable, they have significant limitations for systematic planning [8]:

- Selection Bias: They primarily contain successful reactions, omitting failed attempts, which can lead to over-optimistic expectations.

- Inconsistent Data: Yield definitions and measurement methods can vary significantly between sources.

- Data Gaps: They often lack fine-grained details on concentrations, additives, and precise experimental protocols.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Inconsistent or Irreproducible Reaction Yields

| Potential Cause | Investigation Steps | Recommended Action |

|---|---|---|

| Uncontrolled Impurities | Analyze starting materials and solvents for contaminants (e.g., water, metal traces). | Implement stricter quality control and use purified, anhydrous solvents. |

| OFAT Optimization | Statistically analyze past experimental data for interaction effects between parameters. | Shift to Design of Experiment (DoE) methodologies to efficiently map the parameter space [8]. |

| Insufficient Data on Failed Conditions | Review internal lab notebooks to document all attempts, including failures. | Create a standardized internal database that records all experimental parameters and outcomes, both positive and negative [8]. |

Problem: Inability to Find a Literature Precedent for a Novel Substrate

| Potential Cause | Investigation Steps | Recommended Action |

|---|---|---|

| Over-reliance on Text-Based Searches | Use structure and substructure search features in databases instead of keyword searches. | Draw your reactant and product structures to find reactions with the most similar transformation core. |

| Ignoring Analogous Reaction Classes | Search for reactions that share the same mechanistic step (e.g., oxidative addition, reductive elimination). | Broaden your search to include different reaction types that may proceed through a similar key transition state. |

| Rigid "Nearest-Neighbor" Approach | Manually evaluate the top 5-10 most similar reactions and identify common condition patterns. | Synthesize a new condition set by combining the most frequent catalyst, solvent, and reagent from the similar reactions, rather than copying a single precedent [9]. |

Experimental Protocols: Key Traditional Methodologies

Protocol 1: The "One Factor at a Time" (OFAT) Optimization

This was the traditional standard for reaction optimization in academic and industrial settings [8].

- Baseline Establishment: Run the reaction with literature-reported conditions.

- Parameter Variation: Select one parameter to vary (e.g., solvent) while keeping all others constant (catalyst, temperature, concentration).

- Yield Analysis: Measure the yield for each solvent.

- Iteration: Fix the solvent at the best-performing value and select the next parameter to vary (e.g., temperature). Repeat the process.

- Limitation: This method is inefficient and often fails to find the true optimum because it cannot detect interactions between parameters (e.g., a specific solvent that works best at a specific temperature).

Protocol 2: High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) for Local Optimization

HTE emerged as a powerful tool to generate high-quality, consistent data for specific reaction families, bridging the gap between traditional and data-driven methods [10] [8].

- Reaction Selection: Focus on a single reaction family (e.g., Buchwald-Hartwig amination).

- Plate Design: Use automated robotics to set up numerous parallel reactions in a microtiter plate, systematically varying conditions like catalysts, ligands, bases, and solvents.

- Parallel Execution: Run all reactions simultaneously under controlled temperature and atmosphere.

- Automated Analysis: Use analytical techniques like HPLC or LC-MS to quantitatively determine yields for all experiments in the array.

- Outcome: This generates a dense, high-quality dataset that includes both successful and failed reactions, which is critical for understanding reaction boundaries. These datasets later became the foundation for training local machine learning models [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key components and their functions in traditional reaction condition design [8] [11].

| Research Reagent / Tool | Function & Explanation |

|---|---|

| Reaxys | A proprietary chemical database containing millions of reactions; used to find literature precedents and heuristic rules for condition selection [8]. |

| Open Reaction Database (ORD) | An open-access initiative to collect and standardize chemical synthesis data; aims to provide a more balanced and accessible resource for the community [8]. |

| High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) Robotics | Automated systems that perform a large number of experiments in parallel; essential for generating consistent, high-volume data for optimizing specific reaction types [10] [8]. |

| Solvent Selection Guides | Heuristic charts classifying solvents by polarity, boiling point, and coordinating ability; used to make educated guesses for suitable reaction media. |

| Catalyst-Ligand Maps | Empirical guides that map effective ligand and catalyst pairings for specific reaction classes (e.g., Pd-catalyzed cross-couplings); used to narrow down from thousands of potential combinations. |

Traditional Reaction Condition Design Workflow

The diagram below illustrates the iterative, human-centric process of designing and optimizing reaction conditions before the widespread adoption of AI.

Knowledge Gaps and Limitations of the Pre-AI Era

The table below summarizes the key quantitative and qualitative limitations of relying on expert knowledge and heuristic rules.

| Aspect | Limitation & Impact |

|---|---|

| Data Scarcity & Bias | Commercial databases are biased towards positive results, omitting crucial data on failures. This leads to models that overestimate reaction feasibility and yield [8]. |

| Condition Recommendation | A nearest-neighbor approach, while common, is computationally intensive and cannot infer missing information or guarantee condition compatibility [9]. |

| Optimization Efficiency | The OFAT approach is simplistic and often fails to find true optimal conditions because it ignores interactions between experimental factors [8]. |

| Generalizability | Expert systems and heuristic rules built for specific reaction types (e.g., Michael additions) show limited accuracy and fail to transfer to broader reaction scopes [9]. |

Core Concept Definitions and FAQs

What constitutes the "chemical context" of a reaction?

The chemical context refers to the set of non-reactant substances and physical parameters that enable and influence a chemical transformation. This primarily includes the catalyst, solvent, reagent, and temperature. These elements determine the reaction's pathway, speed, and efficiency.

How does a catalyst function, and why is it crucial?

A catalyst is a substance that speeds up a chemical reaction without being consumed in the process [12]. It works by lowering the activation energy—the energy barrier that must be overcome for the reaction to occur [12]. Furthermore, catalysts often provide selectivity, directing a reaction to increase the amount of desired product and reduce unwanted byproducts [12].

What roles do solvents and reagents play?

- Solvent: The medium in which the reaction occurs. It can solvate reactants, influence reaction rates and mechanisms, and assist in heat transfer.

- Reagent: A substance that is consumed to facilitate the conversion of reactants to products. It is distinct from a catalyst as it is typically used in stoichiometric amounts and is not regenerated.

Why is temperature a critical parameter?

Temperature directly influences the reaction rate, often approximated by the Arrhenius equation. It also affects the solubility of components, the stability of catalysts, and can shift reaction equilibria. Precise temperature control is essential for reproducibility and yield optimization.

Machine Learning for Reaction Condition Prediction

How can Machine Learning (ML) predict suitable reaction conditions?

ML models, particularly neural networks, can be trained on large databases of known reactions (e.g., Reaxys, USPTO) to learn the complex relationships between reactant structures and successful reaction conditions [9] [5]. These models treat the prediction of catalyst, solvent, reagent, and temperature as a multi-objective optimization problem [9].

What is the performance of current ML models?

Trained on approximately 10 million reactions from Reaxys, one state-of-the-art model demonstrates the following top-10 prediction accuracies [9]:

Table 1: Performance of a Neural Network Model for Reaction Condition Prediction

| Predicted Element | Top-10 Prediction Accuracy | Additional Metrics |

|---|---|---|

| Overall Chemical Context (Catalyst, Solvent, Reagent) | 69.6% (close match found) | - |

| Individual Species (e.g., specific solvent or reagent) | 80-90% | - |

| Temperature | 60-70% (within ±20 °C of recorded temp) | Accuracy higher with correct chemical context |

What are the current challenges in ML-based prediction?

Despite progress, challenges remain, including data quality and sparsity, the difficulty of evaluating the "correctness" of proposed conditions, and ensuring the model accounts for the compatibility and interdependence of all context elements and temperature [9] [5]. Some studies suggest that simple, literature-derived popularity baselines can be difficult to surpass [5].

Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ: My reaction failed despite using ML-predicted conditions. What should I do?

Reaction failure can occur even with sophisticated predictions. Follow this systematic troubleshooting protocol, changing only one variable at a time [13].

FAQ: How can I improve my reaction yield?

Table 2: Troubleshooting Low Reaction Yields

| Issue | Potential Solution | ML Integration |

|---|---|---|

| Low Conversion | Increase reaction temperature or time; optimize catalyst loading. | ML models can predict optimal temperature and catalyst [9]. |

| Side Reactions | Modify solvent to control selectivity; use a more selective catalyst; adjust addition rate of reagents. | ML learns solvent/reagent functional similarity for selective choices [9]. |

| Incomplete Mixing | Ensure efficient stirring; change solvent to improve solubility. | - |

| Catalyst Deactivation | Ensure reaction atmosphere is inert; purify reagents to remove inhibitors. | - |

Experimental Protocol for ML-Guided Reaction Optimization

This protocol outlines a Bayesian optimisation workflow for high-throughput experimentation (HTE), as validated in recent literature [3].

Objective: To efficiently identify optimal reaction conditions (catalyst, solvent, reagent, temperature) for a given chemical transformation.

Workflow Overview:

Step-by-Step Methodology:

Define the Condition Search Space:

- Compile a discrete combinatorial set of plausible reaction conditions from chemical knowledge.

- Parameters to include: Catalysts, ligands, solvents, reagents, additives, temperature, concentration.

- Apply practical filters: Exclude conditions with unsafe combinations (e.g., NaH in DMSO) or where temperature exceeds solvent boiling points [3].

Initial Experimental Batch (Sobol Sampling):

- Use algorithmic Sobol sampling to select the first batch of experiments (e.g., a 96-well plate).

- This ensures the initial data points are diversely spread across the entire reaction condition space for maximum information gain [3].

Execute Experiments & Measure Outcomes:

- Perform reactions using an automated HTE platform.

- Measure key objectives (e.g., yield, selectivity, conversion) for each condition.

Train Machine Learning Model:

- Train a Gaussian Process (GP) regressor on the collected experimental data.

- The model will predict reaction outcomes and their associated uncertainties for all untested conditions in the search space [3].

Select Next Experiments via Acquisition Function:

- Use a multi-objective acquisition function (e.g., q-NParEgo, TS-HVI) to select the next batch of experiments.

- The function balances exploration (testing uncertain regions) and exploitation (testing near high-performing conditions) [3].

Iterate to Convergence:

- Repeat steps 3-5 for several iterations.

- The process terminates when performance converges, objectives are met, or the experimental budget is exhausted.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Components for a Reaction Condition Screening Kit

| Item / Component | Function / Role | Example(s) / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Catalyst Library | Speeds up the reaction; key for selectivity. | Palladium (Pd), Nickel (Ni) complexes; organocatalysts. Earth-abundant metals (e.g., Ni) are increasingly favored for sustainability [3]. |

| Solvent Library | Reaction medium; influences mechanism and rate. | Polar protic (e.g., MeOH), polar aprotic (e.g., DMF), non-polar (e.g., Toluene). ML models learn a continuous numerical embedding capturing solvent functional similarity [9]. |

| Reagent/Base Library | Facilitates stoichiometric transformations. | Bronsted bases (e.g., K2CO3), oxidants, reductants. |

| Ligand Library | Binds to a catalyst to modulate its activity and selectivity. | Phosphine ligands, nitrogen-donor ligands. Critical for tuning metal-catalyzed reactions like Suzuki couplings [3]. |

| Additives | Address specific issues like moisture or catalyst inhibition. | Salts (e.g., for ionic strength), stabilizers, inhibitors. |

| High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) Platform | Allows highly parallel execution of numerous reactions at miniaturized scales. | Automated liquid handlers, 96-well plate reactors. Enables rapid data generation for ML models [3]. |

Frequently Asked Questions

FAQ: What are the most common data-related issues in reaction condition prediction?

The primary challenges are dataset scarcity, data quality problems, and the "completeness trap." Dataset scarcity arises because high-quality, labeled reaction data with detailed condition information is limited [14] [15]. Data quality issues include inconsistent reporting, missing failure data, and a lack of standardization [15]. The "completeness trap" refers to the counterproductive pursuit of excessively large but noisy datasets at the expense of data quality and specific relevance [14].

FAQ: What is the 'Completeness Trap' and how can I avoid it?

The "Completeness Trap" is the assumption that larger datasets automatically lead to better models. This can be a pitfall when data volume is prioritized over data quality, relevance, and accurate labeling of reaction conditions [14]. To avoid it:

- Focus on collecting high-quality, well-annotated data for specific reaction types.

- Use targeted data augmentation techniques.

- Implement iterative, active learning cycles where the model guides new experiments, rather than blindly collecting massive datasets [14].

FAQ: My model fails to predict viable conditions beyond simple popularity baselines. What is wrong?

This is a common problem where a model merely replicates the most frequent conditions in the training data without learning the underlying chemistry. This often stems from inadequate reaction representation and dataset bias [15]. Solutions include:

- Moving beyond simple molecular fingerprints to more sophisticated representations like the Condensed Graph of Reaction (CGR), which can capture reaction changes more effectively [15].

- Ensuring your dataset has sufficient variety and is not dominated by a few high-yielding conditions.

- Using alternative input representations that go beyond one-hot encoding of reagents, such as continuous descriptors based on molecular structure or physicochemical properties [15].

FAQ: What experimental protocols can mitigate data scarcity?

Adopt iterative, closed-loop workflows that integrate machine learning with high-throughput experimentation (HTE) [15]. The diagram below illustrates this active learning cycle designed to maximize information gain from minimal experiments.

FAQ: How are 'optimal conditions' defined for machine learning?

The definition is context-dependent. Two main approaches exist [15]:

- Reactant-Specific Conditions: Tailored for a single reactant pair to maximize output (e.g., yield) for late-stage or scale-up chemistry. The objective is formalized as ( c^* = \arg\max_{c \in C} f(r; c) ), where you find the condition ( c ) from a set ( C ) that maximizes an objective function ( f ) (like yield) for reaction ( r ) [15].

- General Conditions: A robust set of conditions that perform well across a range of related reactants, useful for library synthesis or robustness screens. The goal is to find conditions that maximize an aggregate function ( \phi ) (like mean yield) across a reaction type ( R ) [15].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Poor Model Generalization and Performance

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Model consistently predicts only the most common solvents/catalysts. | Dataset bias and inadequate reaction representation [15]. | Use advanced reaction representations (e.g., CGRs) [15]. Apply techniques to handle class imbalance. |

| Model performance is poor on specific reaction sub-types. | The "completeness trap"; data is too generic/noisy [14]. | Refine the dataset for the specific reaction type of interest. Use transfer learning from a general model. |

| Model fails to predict any viable conditions for novel reactants. | Dataset scarcity and the model's limited applicability domain [14]. | Incorporate active learning to target data gaps [14]. Use human-in-the-loop feedback to refine predictions [14]. |

Problem: Data Quality and Preparation Issues

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Missing or inconsistent labels for reagents (e.g., solvent, catalyst). | Lack of standardization in source data [15]. | Implement rigorous data curation protocols. Use coarse-grained categories (e.g., "polar aprotic solvent") to mitigate sparsity [15]. |

| Lack of "negative data" or reaction failures. | Publication and reporting bias [15]. | Generate in-house failure data via HTE. Use assumedly infeasible 'decoy' examples to train two-class classifiers [15]. |

| Difficulty in representing diverse condition elements in a single model. | The complex, multi-component nature of reaction conditions [15]. | Employ structured condition vectors that combine one-hot encoding for reagents and continuous values for parameters like temperature [15]. Use descriptors for reagents (e.g., physicochemical properties) [15]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key computational and experimental resources for building robust models for reaction condition prediction [15].

| Research Reagent / Resource | Function in Reaction Condition Prediction |

|---|---|

| High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) | Rapidly generates large, consistent datasets of reaction outcomes, including failures, which are crucial for training accurate models [15]. |

| Condensed Graph of Reaction (CGR) | A reaction representation that captures the difference between products and reactants, often leading to better predictive performance than reactant-only representations [15]. |

| Bayesian Optimization | An efficient search algorithm for navigating the complex space of reaction conditions to find optimal parameters, often used in an active learning setup [14] [15]. |

| Active Learning | A machine learning paradigm that selectively queries the most informative experiments to be performed, minimizing the data required for model optimization [14]. |

| Open Reaction Database (ORD) | A growing public database of chemical reactions that provides a source of diverse data for training and benchmarking condition prediction models [15]. |

| Human-in-the-Loop Strategy | Integrates the expertise of chemists into the iterative learning cycle, helping to guide the search for conditions and validate model proposals [14]. |

The logical relationships and workflow between these key resources in a modern, data-driven research pipeline are shown below.

In machine learning for reaction condition prediction and drug discovery, the numerical representation of a molecule is the foundational step that determines the success or failure of all subsequent modeling. This technical support guide addresses the core challenges you may encounter when selecting and optimizing molecular representations for your machine learning models. The following sections provide targeted troubleshooting advice, framed within the context of a research thesis on predicting reaction conditions, to help you diagnose and resolve common issues.

Core Concepts & Challenges

Why is molecular representation a primary hurdle?

The choice of molecular representation directly defines the feature space a machine learning model must learn from. An inappropriate representation can create a feature landscape that is difficult for standard models to navigate, leading to poor generalization and high prediction errors. Key challenges include:

- No Universal Solution: No single molecular representation has proven superior across all tasks. The effectiveness of a representation is highly dependent on the specific dataset and prediction target [16].

- Data Scarcity: Deep learning representations often show limited performance with small dataset sizes, which are common in chemical sciences [16] [17].

- Rough Landscapes: Discontinuities in the structure-property relationship, known as Activity Cliffs, can significantly increase the "roughness" of the feature landscape. Models struggle to learn when structurally similar molecules have vastly different properties [16].

FAQ & Troubleshooting Guide

How do I choose the right molecular representation for my task?

Problem: I am unsure whether to use traditional fingerprints, graph-based models, or other representations for my reaction prediction model.

Solution: There is no one-size-fits-all answer, but the following table summarizes common representation types and their typical use cases to guide your selection.

| Representation Type | Examples | Key Features | Best Use Cases | Common Pitfalls |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Fingerprints | ECFP [16], MACCS [16] | Predefined structural keys; binary vectors; computationally efficient. | - Established QSAR/QSPR- Tasks with small datasets- When interpretability is key [16] | May miss complex, non-obvious structural patterns. |

| Graph Representations | GNNs [16], Molecular Graphs [17] | Native representation of atom/bond connectivity; learned features. | - Property prediction where topology is critical [17]- Capturing long-range interactions [17] | Requires well-defined bonds; can struggle with conjugated systems [18]. |

| Set Representations | MSR1, MSR2 [18] | Represents molecules as sets (multisets) of atoms; permutation invariant. | - An alternative to graphs when bonds are not well-defined [18]- Protein-ligand binding affinity [18] | A newer approach, less established than graphs or fingerprints. |

| Learned Representations | Transformers [16], KPGT [17] | Data-driven embeddings; can capture rich semantic information. | - Large, diverse datasets- Foundation models for transfer learning [17] | Heavy dependency on data quality and quantity; pre-training can be complex [17]. |

My model performance has plateaued. Could the molecular representation be the issue?

Problem: Despite hyperparameter tuning, my model's accuracy on molecular property prediction is not improving.

Solution: This is a common symptom of a representation-level problem. We recommend the following diagnostic protocol to systematically evaluate and address the issue.

Diagnostic Protocol:

Quantify Feature Space Topology: Calculate topological descriptors for your feature space. Recent research shows that the Roughness Index (ROGI) and other landscape metrics are strongly correlated with model test error [16]. A high ROGI value suggests a "rough" landscape that is inherently difficult for models to learn.

Analyze with Predictive Models: Leverage existing frameworks like TopoLearn, which predicts model performance based on the topological characteristics of a representation's feature space [16]. This can help you determine if the issue lies with the representation itself.

Evaluate Alternative Representations: Based on the TopoLearn analysis and the table above, test alternative representations. For example, if you are using ECFP, try a graph neural network or a set representation.

Advanced Tactic: Use Intermediate Embeddings: If you are using a pre-trained deep learning model, do not default to the final-layer embeddings. Empirical evidence shows that using frozen embeddings from optimal intermediate layers can improve downstream performance by an average of 5.4%, and sometimes up to 28.6%, compared to the final-layer [19]. Finetuning encoders truncated at these intermediate depths can yield even greater gains.

How can I integrate knowledge to improve representation learning?

Problem: My self-supervised learning model seems to be memorizing data rather than learning meaningful features for reaction yield prediction.

Solution: Incorporate additional knowledge into your pre-training strategy. Pure self-supervised learning on molecular graphs can sometimes lack semantic information.

Methodology: Implement a knowledge-guided pre-training framework like KPGT (Knowledge-guided Pre-training of Graph Transformer) [17].

- Augment the Graph: Add a dedicated Knowledge Node (K-node) to your molecular graph. This node is connected to all other nodes in the graph.

- Initialize with Knowledge: The K-node's feature embedding is initialized using quantitative molecular characteristics (e.g., molecular descriptors or fingerprints) [17].

- Pre-train with Guidance: During pre-training with a masked node prediction objective, the K-node interacts with all other nodes via the model's attention mechanism. This guides the model to capture both structural and rich semantic information, leading to more robust and generalizable molecular representations [17].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials

The following table lists essential computational "reagents" and tools for advanced research in molecular representation learning.

| Item | Function / Description | Relevance to Research |

|---|---|---|

| Topological Data Analysis (TDA) [16] | A mathematical approach to infer and analyze the shape and structure of high-dimensional data. | Correlates geometric properties of feature spaces with ML generalizability; used in models like TopoLearn. |

| Reaxys Database [9] | A large, curated database of chemical reactions, substances, and properties. | Primary data source for training condition prediction models; provides millions of examples for context. |

| Line Graph Transformer (LiGhT) [17] | A transformer architecture designed for molecular line graphs, which represent adjacencies between chemical bonds. | Captures complex bond information and long-range interactions within molecules, improving representation. |

| RepSet / Set Representation Layer [18] | A neural network layer capable of permutation-invariant representation of variable-sized sets. | Core component of Molecular Set Representation Learning (MSR); allows modeling molecules as sets of atoms. |

| Therapeutics Data Commons [17] | A collection of datasets for machine learning across the entire drug discovery and development pipeline. | Provides standardized benchmarks for fair and comprehensive evaluation of new representation methods. |

ML Methodologies and Real-World Applications in Drug Development

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between a global and a local model in reaction condition prediction?

A1: The core difference lies in their scope, data requirements, and primary application.

- Global Models are trained on extensive and diverse datasets covering numerous reaction types. They learn general patterns to provide initial condition suggestions for a wide array of novel reactions, making them ideal for the early planning stages in computer-aided synthesis planning (CASP) [20] [8].

- Local Models are specialized for a single reaction family or a specific optimization campaign. They use finer-grained parameters to precisely optimize conditions like yield and selectivity for that particular context, often leveraging data from High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) [20] [8].

Q2: My global model suggests conditions that seem chemically unreasonable for my specific reaction. What could be wrong?

A2: This is a known limitation of global models. Potential causes and solutions include:

- Data Bias: The training data (e.g., from patents) may be biased towards successful conditions, lacking information on failures and the full range of explorable parameters [8].

- Out-of-Scope Prediction: Your reaction may be too dissimilar from those in the model's training set, causing it to extrapolate poorly [8].

- Solution - Fine-tuning: Consider fine-tuning a pre-trained global model on your local, specialized dataset. This hybrid approach has been shown to outperform either model used in isolation [21].

Q3: When should I invest in building a local model instead of relying on a global one?

A3: You should consider a local model when:

- Optimizing a Key Step: You are focused on a critical reaction in your synthesis and need to maximize yield, selectivity, or other performance metrics [8].

- Sufficient Local Data is Available: You have access to a dedicated dataset, typically from HTE, that explores the parameter space for your specific reaction [8].

- Global Model Performance is Poor: The reaction you are working on is under-represented in public databases, leading to inaccurate predictions from global models [20].

Q4: How can I understand why my model made a specific prediction, especially for a critical reaction?

A4: This requires model explainability techniques, which operate at different levels [22]:

- Local Explainability: For a single prediction, use methods like LIME or SHAP to identify which features (e.g., a specific functional group or solvent) most influenced the outcome for that specific reaction [22].

- Cohort Explainability: To understand model behavior for a subgroup (e.g., all reactions involving a specific catalyst), analyze feature importance across that entire cohort [22].

- Global Explainability: To get an overview of what the model considers important on average across all its predictions [22].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Model Provides Overly General or Chemically Inaccurate Suggestions

This typically indicates a problem with a global model's applicability or training data.

| Probable Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Training Data Bias [8] | Check if the model was trained only on successful reactions from patents/literature. | Use a model incorporating failure data (e.g., from HTE) or apply a fine-tuning step with your own data [21] [8]. |

| Reaction is Out-of-Scope | Assess the structural similarity between your reaction and the model's training set. | Switch to a local model designed for your reaction family or employ a fine-tuned hybrid model [21]. |

| Poor Molecular Representation [23] [24] | Evaluate how molecules and conditions are featurized (e.g., SMILES, fingerprints, graphs). | Consider models using advanced graph-based representations that better capture structural and interactive chemistry, such as graph transformers [25] [24]. |

Issue: Local Model Fails to Generalize Within Its Reaction Family

This often occurs when a local model overfits to its limited training data.

| Probable Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Insufficient or Low-Quality Data [8] | Review the size and variance of your HTE dataset. Ensure it includes failed experiments (zero yields) [8]. | Expand the experimental dataset using design-of-experiments (DoE) or active learning. Use Bayesian Optimization to guide data collection efficiently [8]. |

| Incorrect Assumption of Reaction Homogeneity | Verify that all reactions in the training set follow the same mechanism. | Re-cluster your reaction data or build separate models for distinct mechanistic sub-families. |

| Overfitting | Check for a large performance gap between training and validation error. | Apply stronger regularization, simplify the model architecture, or increase the training dataset size. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Building a Global Reaction Condition Recommender

Objective: To train a model that suggests general reaction conditions (e.g., catalyst, solvent) for a diverse set of organic reactions.

Materials & Datasets:

- Primary Data Source: Large-scale databases like Reaxys (proprietary) or the Open Reaction Database (ORD) (open access) [8].

- Preprocessing Tools: RDKit for molecule standardization and descriptor calculation [23].

- Model Architecture: Transformer-based or Graph Neural Network (GNN) models are state-of-the-art [23] [24].

Methodology:

- Data Curation: Extract millions of reactions from the chosen database. Focus on key fields: reactants, products, catalysts, solvents, and yields [8].

- Reaction Representation:

- Sequence-based: Represent the entire reaction as a SMILES string for transformer models [24].

- Graph-based: Represent molecules as graphs and use GNNs to learn structural features. More advanced models like log-RRIM use a local-to-global strategy, first learning molecule-level information and then modeling interactions between them [25] [24].

- Model Training: Train a classification or ranking model. The input is the reaction context (e.g., product or reactants), and the output is a probability distribution over a predefined list of possible conditions [8].

- Validation: Evaluate the model's top-k accuracy in recommending the correct conditions on a held-out test set from the database [23].

Protocol 2: Optimizing Conditions with a Local Model via Bayesian Optimization

Objective: To find the optimal combination of continuous (e.g., temperature, concentration) and categorical (e.g., ligand, base) parameters to maximize the yield of a specific reaction.

Materials & Datasets:

- Primary Data Source: High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) data for the target reaction family (e.g., Buchwald-Hartwig amination) [8].

- Optimization Framework: Bayesian Optimization (BO) libraries like Ax or BoTorch.

- Initial Dataset: A small, space-filling design (e.g., 20-50 data points) to initialize the model.

Methodology:

- Experimental Design: Use an HTE platform to conduct the initial set of experiments, varying key parameters as defined by the design [8].

- Model Initialization: Train a probabilistic model (commonly a Gaussian Process) on the initial HTE data to map reaction conditions to yield [8].

- Iterative Optimization Loop: a. Propose: The acquisition function (e.g., Expected Improvement) suggests the next most promising condition(s) to test. b. Experiment: Conduct the proposed experiment(s) using robotic automation or manual synthesis. c. Update: Add the new condition-yield data to the training set and update the model.

- Convergence: Repeat steps 3a-3c until a yield threshold is met or the experimental budget is exhausted [8].

Workflow and System Diagrams

Global vs Local Model Workflow

Local-to-Global Representation in log-RRIM

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This table details key computational and data "reagents" essential for work in this field.

| Tool / Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Reaxys [8] | Chemical Database | Proprietary source of millions of experimental reactions for training global models. |

| Open Reaction Database (ORD) [8] | Chemical Database | Open-source initiative to collect and standardize chemical synthesis data for reproducible model development. |

| RDKit [23] | Cheminformatics Software | Provides essential tools for molecule manipulation, fingerprint generation, and reaction template extraction. |

| Graph Neural Network (GNN) [23] [24] | Machine Learning Model | Architecture that represents molecules as graphs to directly learn from structural data. |

| log-RRIM [25] [24] | ML Framework | A specialized graph transformer that uses a local-to-global strategy and cross-attention to model reactant-reagent interactions for yield prediction. |

| Bayesian Optimization (BO) [8] | Optimization Algorithm | Efficiently guides high-throughput experimentation by suggesting the most promising conditions to test next. |

| SHAP/LIME [22] | Explainability Tool | Provides post-hoc explanations for model predictions, crucial for debugging and building trust. |

Troubleshooting Guide: Machine Learning for Reaction Condition Prediction

This guide addresses common challenges researchers face when implementing machine learning algorithms for predicting and optimizing chemical reaction conditions.

Question: My model, trained on one type of chemical reaction, performs poorly when applied to a new reaction class. What strategies can I use to improve its generalizability?

Answer: This is a classic problem of model transfer. The performance drop often occurs when the new reaction (target domain) has a different underlying mechanism or data distribution from the original reaction (source domain) [26] [8].

- Diagnosis: First, assess the mechanistic similarity between the source and target reactions. A model trained on C-N coupling reactions (e.g., using amide nucleophiles) may transfer well to other C-N couplings (e.g., with sulfonamides) but fail completely for C-C couplings (e.g., with boronate esters) [26].

- Solution: Implement Active Transfer Learning. Combine transfer learning with active learning. Use the source model as an intelligent starting point, then actively select the most informative experiments to run in the target domain. This builds a performant model for the new reaction with minimal new data [26].

- Protocol: Active Transfer Learning for a New Reaction:

- Start with a pre-trained model from a related, data-rich reaction domain.

- Design a small, initial set of experiments for the new reaction.

- Use an active learning criterion (e.g., uncertainty sampling) to select which reaction conditions to test next. The model identifies areas where it is most uncertain.

- Run the experiments and collect the yields.

- Update the model with the new data.

- Repeat steps 3-5 until a performance threshold is met or the experimental budget is exhausted [26].

The table below summarizes quantitative results from a study on transferring models between different nucleophile types in Pd-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions, illustrating this challenge [26].

Table 1: Model Transfer Performance Between Nucleophile Types (ROC-AUC Score)

| Source Nucleophile (Training Data) | Target Nucleophile (Testing Data) | Transfer Performance (ROC-AUC) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Benzamide | Sulfonamide | 0.928 | High performance; mechanistically similar (C-N coupling) |

| Benzamide | Pinacol Boronate Ester | 0.133 | Poor performance; different mechanism (C-B coupling) |

| Sulfonamide | Benzamide | 0.880 | High performance; mechanistically similar (C-N coupling) |

| Sulfonamide | Pinacol Boronate Ester | 0.148 | Poor performance; different mechanism (C-B coupling) |

The following diagram illustrates the active transfer learning workflow for adapting a model to a new reaction:

Question: When using Bayesian Optimization for reaction optimization, my process seems to get stuck in a local optimum. How can I encourage more exploration of the reaction space?

Answer: Getting stuck is often a result of an imbalance between exploitation (using known high-yielding conditions) and exploration (testing uncertain regions that may hold better yields) [27] [28].

- Diagnosis: Check the acquisition function's behavior. If it consistently suggests points very close to the current best, it is over-exploiting.

- Solution: Tune the Acquisition Function.

- For the Expected Improvement (EI) function, increase the

ξ(xi) parameter. This parameter explicitly controls the trade-off; a higherξvalue gives more weight to exploration [27] [28]. - Consider using the Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) acquisition function, which has a built-in parameter

κto explicitly control exploration weight [28].

- For the Expected Improvement (EI) function, increase the

- Protocol: Bayesian Optimization for Reaction Optimization:

- Define the search space: Identify key variables to optimize (e.g., catalyst loading, temperature, solvent ratio) and their bounds.

- Choose a surrogate model: A Gaussian Process (GP) is commonly used as it provides uncertainty estimates [27] [28].

- Select an acquisition function: Expected Improvement (EI) is a popular default [28].

- Run the iterative optimization loop:

a. Fit the GP to all data collected so far.

b. Find the reaction conditions

xthat maximize the acquisition function. c. Run the experiment atxand measure the yieldy. d. Add the new data point(x, y)to the dataset. - Monitor and adjust: If optimization stalls, increase the exploration parameter in the acquisition function.

The table below compares common acquisition functions used in Bayesian Optimization [27] [28].

Table 2: Key Acquisition Functions in Bayesian Optimization

| Acquisition Function | Key Principle | How to Encourage Exploration |

|---|---|---|

| Probability of Improvement (PI) | Selects point with highest probability of beating the current best yield. | Increase the ϵ parameter to require a more significant improvement. |

| Expected Improvement (EI) | Selects point with highest expected value of improvement over current best. | Increase the ξ parameter. |

| Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) | Selects point using a weighted sum of the predicted mean and uncertainty. | Increase the κ parameter to weight the uncertainty term more heavily. |

The following diagram illustrates the Bayesian Optimization loop and the role of the acquisition function:

Question: The human-in-the-loop system in my automated workflow is not triggering, and tool calls are executed without human review. What could be wrong?

Answer: This typically indicates an implementation error in how the interruption for human review is defined and integrated with the tool [29].

- Diagnosis: This is often a code-level issue. Check that the tool is correctly wrapped with the human-in-the-loop logic and that the underlying framework is configured properly [29].

- Solution:

- Wrap the tool correctly: Ensure the tool function is passed through a dedicated wrapper (e.g.,

add_human_in_the_loop) that overrides its invocation to include an interrupt request [29]. - Check the framework configuration: When using development servers (e.g.,

langgraph dev), verify that no incompatible configurations are blocking the interrupt. Using anInMemorySaveris often recommended for this purpose [29]. - Verify the frontend: The user interface (e.g., LangGraph Agent Chat UI) must be designed to recognize and display the specific interrupt type for human review [29].

- Wrap the tool correctly: Ensure the tool function is passed through a dedicated wrapper (e.g.,

- Protocol: Implementing a Human-in-the-Loop Tool Call:

- Define the base tool (e.g.,

book_hotel) with its name, description, and arguments [29]. - Create a wrapper function that replaces the original tool's execution logic.

- Inside the wrapper, request an interrupt. The interrupt sends a structured request to the UI, pausing the workflow and asking for human input (e.g., Accept, Edit, or Respond with feedback) [29].

- Invoke the original tool only if the human response is "Accept" or "Edit". If "Edit", use the human-provided arguments. If "Respond", return the feedback directly to the AI agent [29].

- Define the base tool (e.g.,

Question: I have very limited data for my specific reaction of interest. Which ML approach should I use?

Answer: In low-data regimes, the choice of strategy depends on the availability of data from a related, larger dataset.

- If a large, related dataset exists: Use Transfer Learning. Train a model on the large source dataset and fine-tune it on your small, target dataset. This provides a strong inductive bias [26] [8].

- If no large dataset exists: Use Active Learning. Start with a small random set of experiments, then iteratively select the most informative next experiments based on model uncertainty. This maximizes information gain from a limited experimental budget [26] [30].

- For a balanced approach: Use Active Transfer Learning, which combines both strategies for the most efficient exploration [26].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This table details key components used in a featured study on Pd-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions, a common testbed for these ML algorithms [26].

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Pd-Catalyzed Cross-Coupling HTE

| Reagent | Function in Reaction | Role in ML Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Palladium Catalyst | Central metal catalyst that facilitates the bond formation. | A key categorical variable for the model to optimize. |

| Ligand (Phosphine) | Binds to the Pd catalyst, modifying its reactivity and selectivity. | A critical, high-impact parameter that interacts with other conditions. |

| Base | Neutralizes the byproduct (e.g., HX) to drive the reaction forward. | An essential variable that can be screened from a predefined set. |

| Solvent | Medium that dissolves the reactants and influences reaction kinetics. | A categorical feature with a large search space for the model to navigate. |

| Aryl Halide (Electrophile) | One of the coupling partners. Its structure can vary. | Input feature for the model; its properties are used as descriptors. |

| Nucleophile (e.g., Amine, Boronic Acid) | The other coupling partner. The type (N, C, O-based) defines the reaction. | Defines the reaction domain. Transfer between different nucleophiles is a key test [26]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental advantage of using a Graph Neural Network over traditional machine learning for reaction prediction?

Traditional machine learning models require manually engineered features (descriptors) as input, which can be time-consuming to create and may miss important structural information. GNNs, by contrast, automatically learn meaningful representations directly from the graph structure of a molecule or reaction [31]. They inherently understand that the properties of an atom are influenced by its surrounding molecular context, allowing them to capture complex, non-linear relationships that are difficult to hand-code [32] [33].

Q2: My model's performance seems to saturate or even degrade when I add more MPNN layers. Why does this happen?

This is a common issue known as over-smoothing. In an MPNN, each message-passing step aggregates information from a node's immediate neighbors [34]. After too many layers, the representations of all nodes can become very similar because they have all incorporated information from nearly the entire graph [35]. This washes out the distinctive features needed for prediction. To troubleshoot:

- Reduce the number of layers: Start with a number of layers commensurate with the diameter of the graphs in your dataset.

- Use skip connections: These allow information from earlier, less-smoothed layers to bypass later ones.

- Explore advanced layers: Consider using layers like gated graph networks or attention mechanisms that can better control the flow of information [34] [35].

Q3: How can I represent an entire chemical reaction, not just a single molecule, as a graph for a GNN?

Representing a reaction is a key challenge. Simply using the product molecule's graph ignores the reaction's history. A powerful method is to use a Condensed Graph of Reaction (CGR) [15]. A CGR is a superposition of the reactant and product graphs, where atoms are nodes and bonds are edges. In a CGR:

- Nodes (atoms) are labeled with changes in their properties (e.g., charge, atom type).

- Edges (bonds) are labeled with their change in bond order (e.g., from single to double). This representation explicitly encodes the transformation of the reaction, which has been shown to enhance predictive power for condition prediction tasks [15].

Q4: My model achieves high accuracy but its explanations don't make chemical sense. What can I do?

This indicates your model may be learning from spurious correlations instead of genuine chemical principles, a phenomenon known as the "Clever Hans" effect [33]. To improve explainability:

- Use explanation-guided learning: Incorporate ground-truth explanations into the training process. For example, for activity cliffs (structurally similar molecules with large potency differences), you can supervise the model to ensure its attributions highlight the correct differentiating substructures [33].

- Choose chemist-friendly interpretation methods: Prioritize explanation methods that highlight chemically meaningful molecular substructures rather than just individual atoms or bonds [33].

Q5: The graphs in my dataset have a highly variable number of nodes. How can I train a model on such data?

GNNs are naturally suited for this as they process each node in the context of its local neighborhood, regardless of the overall graph size [32] [36]. Technically, this is handled by:

- Batch Processing: Graphs are batched together by creating a single "disconnected" graph containing all the small graphs. This is memory-efficient and allows for parallel processing [34].

- Permutation Invariance: The core operations of a GNN (message passing and aggregation) are designed to be invariant to the order of nodes and the sizes of graphs, ensuring consistent performance [34] [35].

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol 1: Building a Basic Message Passing Neural Network (MPNN) for Molecular Property Prediction

This protocol outlines the steps to construct an MPNN as defined by Gilmer et al. [34].

1. Input Featurization:

- Nodes: Represent each atom. Common features include atom type, degree, hybridization, and valence.

- Edges: Represent each bond. Common features include bond type (single, double, etc.), and whether it is in a ring.

- Graph: The molecule is represented as an adjacency list detailing the connections between atoms [32].

2. Message Passing Phase (Iterate for T steps):

- Message Function ((Mt)): For each node, a message is computed from each of its neighbors. A common approach is the Edge Network: (M(hv, hw, e{vw}) = A(e{vw})hw) where (A) is a neural network that processes the edge features (e_{vw}) [34].

- Aggregation ((\bigoplus)): The messages from all neighbors are aggregated into a single vector, typically using a sum or mean operation, which is permutation invariant. (mv^{t+1} = \sum{w \in N(v)} Mt(hv^t, hw^t, e{vw}))

- Update Function ((Ut)): The node's current state is updated using the aggregated message. This is often done with a Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU) or a simple Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP). (hv^{t+1} = Ut(hv^t, m_v^{t+1}))

3. Readout Phase (Graph-Level Prediction):

- After T message-passing steps, a readout function generates a graph-level representation. This must also be permutation invariant. (\hat{y} = R({h_v^T \mid v \in G}))

- A simple readout is the global mean of all final node embeddings. For more expressiveness, a set2set model (an attention-based readout) can be used [34].

The following diagram illustrates the message-passing process for one node over two steps.

Message Passing Over Two Steps

Protocol 2: A Case Study in Predicting Conditions for Suzuki–Miyaura Reactions

This protocol summarizes a modern approach to predicting reaction conditions, highlighting the importance of representation [15].

1. Data Curation:

- Source: Reactions were extracted from US patent data (USPTO) and focused specifically on heteroaromatic Suzuki–Miyaura couplings [15].

- Challenge: Data sparsity and the "many-to-many" relationship between reactions and viable conditions.

2. Reaction Featurization:

- Method: Compare different graph-based representations of the reaction.

- Baseline: A popularity baseline, which simply recommends the most common conditions in the training data.

- Test Input: Condensed Graph of Reaction (CGR) representations were used as input to the model and demonstrated enhanced predictive power beyond the popularity baseline [15].

3. Model Training & Evaluation:

- The model is trained to map the featurized reaction input to a condition vector (c).

- Performance is evaluated by the model's ability to correctly predict the true conditions for a held-out test set of reactions, and critically, whether it can outperform the simple popularity baseline [15].

The table below compares different GNN architectures to help select the right model for your task.

| Architecture | Core Mechanism | Key Advantages | Common Use-Cases | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Graph Convolutional Network (GCN) [35] | Spectral graph convolution approximation. | Conceptual simplicity, fast operation, suitable for large graphs. | Node classification, graph classification. | Does not natively support edge features. Can suffer from over-smoothing. |

| Graph Attention Network (GAT) [35] | Self-attention on neighbor nodes. | Weights importance of neighbors dynamically. More expressive than GCN. | Tasks where some neighbors are more important than others. | Slightly more computationally intensive than GCN. |

| Message Passing Neural Network (MPNN) [34] | General framework of message functions and update functions. | Highly flexible, supports both node and edge features. Unifies many GNN variants. | Molecular property prediction, physical systems [34] [33]. | Designing the message/update functions requires careful consideration. |

| Gated Graph Sequence NN [35] | Uses gated recurrent units (GRUs) for state update. | Can model long-range dependencies and output sequences. | Learning algorithms, generating molecular sequences. | More complex and can be harder to train. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This table lists essential computational "reagents" for building GNN models in reaction prediction.

| Item / Solution | Function / Purpose | Example / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Graph Representation | Defines the fundamental input data structure for the model. | Molecular Graph: Nodes=atoms, Edges=bonds. CGR: Encodes reaction transformation [15]. |

| Node Features | Provides initial numerical description of each atom. | Atom type, atomic number, degree, hybridization, formal charge. |

| Edge Features | Provides numerical description of each bond. | Bond type (single, double, aromatic), stereochemistry, bond length. |

| Message Function ((M_t)) | Defines the information sent between connected nodes. | Edge Network: Uses a neural network to transform neighbor features based on edge data [34]. |

| Readout Function ((R)) | Generates a fixed-size representation of the entire graph. | Set2Set: An advanced, attention-based readout. Global Mean/Sum: Simpler, permutation-invariant operations [34]. |

| Explanation-Guided Loss | Aligns model reasoning with domain knowledge. | Used in frameworks like ACES-GNN to ensure attributions are chemically meaningful, especially for activity cliffs [33]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the most significant challenges when using Machine Learning (ML) for reaction condition prediction in High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE)?

The primary challenges in ML for reaction condition prediction include data quality, data sparsity, the choice of reaction representation, and robust method evaluation. Models can fail to outperform simple, literature-derived popularity baselines if these issues are not addressed. Using advanced representations, such as the Condensed Graph of Reaction, has been shown to enhance a model's predictive power and help overcome these hurdles [5].

Q2: How can I troubleshoot a complete failure in my automated ML experiment pipeline?

To diagnose a failed automated ML job, follow these steps [37]:

- Check the main job's status for a failure message.