Machine Learning in Reaction Optimization: From Algorithms to Industrial Applications in Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive overview of machine learning (ML) strategies for optimizing chemical reaction conditions, a critical step in pharmaceutical development.

Machine Learning in Reaction Optimization: From Algorithms to Industrial Applications in Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of machine learning (ML) strategies for optimizing chemical reaction conditions, a critical step in pharmaceutical development. We explore the foundational principles of applying ML to reaction optimization, contrasting traditional one-factor-at-a-time approaches with modern data-driven methods. The piece delves into specific ML methodologies, including Bayesian optimization, high-throughput experimentation (HTE) integration, and transfer learning, illustrated with real-world case studies from drug synthesis. We address key challenges such as data scarcity, model selection for small datasets, and algorithmic bias, offering practical troubleshooting guidance. Finally, the article presents a comparative analysis of ML performance against human-driven design and discusses the validation of these methods through successful industrial applications, including the rapid development of active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) syntheses. This content is tailored for researchers, scientists, and professionals in drug development seeking to leverage ML for accelerated process development.

The New Paradigm: Foundations of Machine Learning in Chemical Reaction Optimization

The Limitations of Traditional One-Factor-at-a-Time (OFAT) Optimization

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What is the main reason my OFAT experiments keep missing the optimal reaction conditions? The most probable reason is that your experimental factors have interaction effects that OFAT cannot detect [1]. OFAT assumes that factors act independently, but in complex chemical or biological systems, factors like temperature and catalyst concentration often work together synergistically. When you optimize one factor at a time while holding others constant, you can get trapped in a local optimum and miss the true global best conditions [2].

2. My OFAT approach worked in development, but now my process is unstable at production scale. Why? This is a classic symptom of OFAT's inability to model factor interactions and build robust systems [1] [3]. What appears optimal at lab scale may reside on a "knife's edge" in the multi-factor space. Small, inevitable variations in other factors during scale-up can dramatically impact outcomes because OFAT doesn't characterize the combined effect of variations [1].

3. Is OFAT ever the right approach for troubleshooting? OFAT can be appropriate for initial, simple troubleshooting where you suspect a single root cause, such as identifying which specific reagent in a protocol has degraded [4]. However, for system optimization, understanding complex behaviors, or when interactions are suspected, statistically designed experiments are vastly superior [1] [3].

4. How can machine learning help overcome the limitations I'm experiencing with OFAT? Machine learning (ML) models, particularly when trained on data from designed experiments (DOE) or high-throughput experimentation (HTE), can directly address OFAT's shortcomings. They can map the entire experimental landscape, capturing complex interactions and non-linear effects to predict optimal conditions that OFAT would likely miss [5]. ML algorithms like Bayesian Optimization can then guide experiments to efficiently find the true optimum with fewer resources [5] [6].

Troubleshooting Guide: Shifting from OFAT to Advanced Methods

| Problem Scenario | Typical OFAT Outcome & Limitation | Recommended Solution & Tools |

|---|---|---|

| Poor Yield Optimization: Despite extensive testing, reaction yields have plateaued at a suboptimal level. | OFAT varies catalysts, temperatures, and solvents separately, missing critical interactions. The identified "optimum" is often a local, not global, maximum [2] [6]. | Implement a Design of Experiments (DOE) approach using a Central Composite or Box-Behnken design. Follow with ML-based response surface modeling to visualize the multi-factor relationship and identify the true optimum [1] [5]. |

| Scale-Up Failure: Process that worked perfectly at benchtop scale performs poorly or inconsistently in pilot-scale reactors. | OFAT does not test how factors like mixing time and heat transfer vary together, failing to build in robustness against natural process variations [1]. | Use DOE principles (Randomization, Replication, Blocking) during development to understand variation sources. Employ ML-powered multi-objective optimization to find a parameter space that is both high-performing and robust to scale-up variations [1] [5]. |

| Lengthy Optimization Cycles: Each new reaction or process requires months of tedious, sequential testing. | OFAT is inherently inefficient, requiring a large number of runs for the precision it delivers. Testing 5 factors at 3 levels each takes 121 runs with OFAT [1] [2]. | Adopt High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) coupled with Machine Learning. HTE collects large, multi-factor datasets rapidly, which are used to train ML models for accurate prediction, drastically reducing experimental cycles [5] [6]. |

Experimental Protocol: Transitioning to a DOE and ML Workflow

This protocol outlines a systematic method to replace OFAT for optimizing a chemical reaction yield, using a two-factor scenario as a foundational example.

1. Define Objectives and Factors

- Objective: Maximize the reaction yield.

- Factors: Identify critical process parameters. For this example: Factor A (Catalyst Concentration) and Factor B (Temperature).

- Response: Quantitative measure of success (e.g., % Yield measured by HPLC).

2. Select and Execute an Experimental Design

- Instead of testing Catalyst Concentration and Temperature separately (OFAT), use a Full Factorial Design with center points.

- This involves running experiments at all possible combinations of your chosen factor levels. A 2-factor, 3-level design is shown below. The inclusion of center points allows for checking curvature in the response.

Table: 2-Factor, 3-Level Full Factorial Design Matrix

| Standard Order | Run Order | Factor A: Catalyst (mol%) | Factor B: Temp (°C) | Response: Yield (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3 | 1.0 | 80 | 65 |

| 2 | 5 | 2.0 | 80 | 78 |

| 3 | 1 | 1.0 | 100 | 72 |

| 4 | 6 | 2.0 | 100 | 95 |

| 5 | 2 | 1.5 | 90 | 85 |

| 6 | 4 | 1.5 | 90 | 83 |

3. Analyze Data and Build a Model

- Statistically analyze the results using regression or ANOVA to build a predictive model.

- The model will quantify the main effect of each factor and, crucially, their interaction effect.

- The model equation might take the form:

Yield = β₀ + β₁(A) + β₂(B) + β₁₂(A*B)

4. Optimize and Validate

- Use the model to generate a response surface plot and identify the predicted optimal factor settings.

- Run a confirmation experiment at these predicted settings to validate the model's accuracy.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Key Resources for Moving Beyond OFAT

| Item or Tool | Function & Relevance |

|---|---|

| JMP Software | A statistical discovery tool that provides a powerful, visual environment for designing experiments (DOE) and analyzing complex data, making it easier to transition from OFAT [2]. |

| High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) Robotics | Automated platforms that enable the rapid execution of hundreds or thousands of experiments in parallel. This is essential for gathering the large, high-quality datasets needed to train machine learning models for reaction optimization [5]. |

| Open Reaction Database (ORD) | A community-driven, open-access resource aiming to standardize and share chemical synthesis data. Such databases are critical for developing robust, globally-applicable machine learning models for condition prediction [5]. |

| Bayesian Optimization (BO) Algorithms | An ML-driven search strategy that is highly sample-efficient. It is particularly well-suited for "self-optimizing" chemical reactors, where it intelligently selects the next experiment to perform to rapidly converge on the optimum [5] [6]. |

| Plackett-Burman Designs | A specific class of highly efficient screening designs that allow you to study multiple factors (n-1) in a very small number (n) of runs. This is more efficient than OFAT for identifying the most important factors to study further [3]. |

Understanding the Fundamental Flaw of OFAT

The core limitation of OFAT is its underlying assumption that factors do not interact. The diagram below contrasts the OFAT and DOE/ML approaches, highlighting how this assumption leads to failure.

OFAT vs. DOE: A Quantitative Comparison

The disadvantages of OFAT become more pronounced and costly as the complexity of your system increases. The following table quantifies this inefficiency.

Table: Efficiency Comparison for Reaching a Conclusion

| Experimental Scenario | Typical OFAT Runs | Typical DOE Runs | Key Advantage of DOE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Screening: 5 Factors (Identify which of 5 potential factors are important) | 46 runs (testing 10 levels for the first factor and 9 for each subsequent one) [2]. | 12-16 runs (using a fractional factorial or Plackett-Burman design) [2] [3]. | 70-75% fewer runs, providing a massive efficiency gain in the initial project phase. |

| Optimization: 2 Factors (Find optimal settings for 2 continuous factors) | 19 runs (as demonstrated in the JMP example) [2]. | 14 runs (using a response surface design) [2]. | 26% fewer runs while also modeling interactions and curvature, leading to a more reliable optimum. |

| Reliability: Finding the True Optimum (Probability of successfully locating the best parameter settings on a complex response surface) | Low (~25-30% success rate in simulation) [2]. | High (Effectively 100% with a properly designed and modeled experiment). | Dramatically higher confidence in the results and the performance of the developed process. |

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What is Machine Learning, and how does it differ from traditional computational chemistry? Machine Learning (ML) is a subset of artificial intelligence that enables computers to identify patterns and make predictions from data, rather than following only pre-programmed rules [7]. Unlike traditional computational chemistry that relies on solving explicit physical equations, ML uses statistical models to learn the relationship between a molecule's features and its properties from existing data, creating a predictive model that can generalize to new, unseen molecules [8] [9].

Q2: What are the main types of Machine Learning relevant to chemistry? The three primary types are:

- Supervised Learning: Used with labeled data to predict known outcomes. Common tasks include predicting reaction yield (regression) or classifying a molecule's activity (classification) [7].

- Unsupervised Learning: Used to discover hidden patterns or groupings in unlabeled data, such as clustering different reaction types or reducing the dimensionality of complex spectral data [7].

- Reinforcement Learning: Involves an agent learning to make optimal decisions through trial-and-error interactions with an environment. It shows promise for optimizing multi-step synthetic pathways [7].

Q3: What are "features" and "labels" in a chemical ML problem?

- Features: These are the measurable attributes or descriptors of a molecule or reaction that you input into the model. Examples include molecular weight, presence of functional groups, solvent polarity, catalyst loading, or temperature [7].

- Labels: This is the target value or outcome you want the model to predict, such as reaction yield, selectivity, solubility, or toxicity [7].

Q4: Why is data cleaning so important, and what are common issues? Data cleaning is often the most time-consuming step because high-quality data is the foundation of a reliable model [7]. Common issues in chemical datasets include:

- Missing values from incomplete experimental records.

- Inconsistent formatting (e.g., mixing "µL" and "mL").

- Outliers due to experimental error.

- Incorrect entries that violate chemical rules (e.g., impossible bond lengths) [7]. Thorough data cleaning dramatically improves model robustness and prevents costly errors in prediction [7].

Q5: How do I handle categorical chemical data, like solvent or ligand names? Categorical variables must be converted into a numerical form. Common methods include:

- One-Hot Encoding: Creates a new binary feature for each category. Ideal for a small number of solvents.

- Label Encoding: Assigns a unique integer to each category. Use with caution as it can imply a false order.

- Target Encoding: Replaces a category with the average value of the target label for that category. Powerful but requires careful validation to avoid data leakage [7].

Q6: What is the bias-variance tradeoff? This is a crucial concept for evaluating model performance [7]:

- High Bias: The model is too simple and underfits the data, making strong assumptions and leading to systematic errors on both training and test data.

- High Variance: The model is too complex and overfits the data, learning the noise in the training set and performing poorly on new data. The goal is to find a model that is complex enough to capture the true chemical patterns but simple enough to ignore noise [7].

Q7: How should I evaluate my ML model's performance? A rigorous experimental design is key [10]:

- Split your data: Divide your dataset into a training set (e.g., 70%) and a test set (e.g., 30%). The test set must be set aside and not used for any model decisions until the very end [10].

- Use cross-validation: On the training set, use techniques like k-fold cross-validation to tune model parameters. This involves splitting the training data into 'k' folds, training on k-1 folds, and validating on the remaining fold, repeating this process k times. This provides a better estimate of generalization error and model variance [10].

- Final test: Evaluate the final chosen model on the held-out test set only once to get an unbiased estimate of its performance on new data [10].

Q8: My model performs well in training but poorly on new data. What went wrong? This is a classic sign of overfitting, where the model has memorized the training data instead of learning generalizable patterns [10]. Other possible causes include:

- Covariate Shift: The training and test data have different underlying distributions (e.g., different impurity profiles) [10].

- Data Snooping: Information from the test set was inadvertently used during training or feature selection [10].

- Insufficient Training Data: The model failed to learn the underlying chemical relationships.

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

| Problem Area | Specific Issue | Potential Causes | Solutions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Quality | Model predictions are chemically impossible. | - Incorrect data entries.- Missing critical features.- Data not representative of chemical space. | - Perform domain expert review.- Apply chemical rule-based filters.- Use data augmentation. |

| Model performance is inconsistent. | - High variance in experimental data.- Inconsistent data reporting. | - Increase dataset size.- Standardize data collection protocols.- Use ensemble methods. | |

| Model Performance | High training accuracy, low test accuracy (Overfitting). | - Model too complex for available data.- Training data not representative. | - Simplify the model.- Increase training data.- Apply regularization (L1/L2). |

| Consistently poor performance on all data (Underfitting). | - Model too simple.- Features lack predictive power.- Incorrect algorithm choice. | - Add more relevant features.- Use a more complex model.- Perform feature engineering. | |

| Algorithm & Training | The optimization process is not finding good reaction conditions. | - Poor balance between exploration and exploitation.- Search space too large or poorly defined. | - Use Bayesian Optimization with a different acquisition function (e.g., EI, UCB).- Incorporate prior chemical knowledge to constrain the space. |

| Training is taking too long or won't converge. | - Learning rate too high or too low.- Poorly scaled features. | - Scale/normalize numerical features.- Tune hyperparameters. |

Real-World Case: ML-Guided Reaction Optimization

The following table summarizes a real-world application of ML for optimizing chemical reactions, as demonstrated by the Minerva framework [11].

| Aspect | Description & Application |

|---|---|

| Objective | Multi-objective optimization of reaction conditions (e.g., maximize yield and selectivity) for pharmaceutically relevant transformations [11]. |

| ML Technique | Bayesian Optimization with Gaussian Process (GP) regressors and scalable acquisition functions (e.g., q-NParEgo, TS-HVI) for large batch sizes (e.g., 96-well plates) [11]. |

| Chemical Transformation | Nickel-catalysed Suzuki coupling; Palladium-catalysed Buchwald-Hartwig amination [11]. |

| Key Outcome | Identified high-performing conditions (>95% yield and selectivity) for an API synthesis in 4 weeks, significantly faster than a previous 6-month development campaign [11]. |

| Experimental Workflow | 1. Define a plausible reaction condition space.2. Initial exploration via diverse sampling (e.g., Sobol sequence).3. Use ML to select the next batch of experiments.4. Iterate rapidly with automated high-throughput experimentation (HTE) [11]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Solutions

This table details essential components for building and running an ML-driven reaction optimization campaign.

| Item | Function in ML-Driven Experiment |

|---|---|

| High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) Robotic Platform | Enables highly parallel execution of numerous miniaturized reactions, generating the large datasets needed for effective ML training [11]. |

| Chemical Descriptors / Fingerprints | Numerical representations of molecular structure (e.g., functional groups, atom types, 3D coordinates) that allow ML algorithms to "understand" the chemistry [8]. |

| Bayesian Optimization Algorithm | An efficient strategy for globally optimizing black-box functions. It balances exploring uncertain regions of the reaction space and exploiting known promising conditions [11]. |

| Gaussian Process (GP) Regressor | A core model in Bayesian Optimization that predicts reaction outcomes and, crucially, quantifies the uncertainty of its predictions for new, untested conditions [11]. |

| Acquisition Function (e.g., Expected Improvement) | Guides the selection of the next experiments by mathematically formalizing the trade-off between exploration and exploitation based on the GP's predictions [11]. |

| Sobol Sequence | A quasi-random sampling method used to select an initial batch of experiments that are well-spread and diverse across the entire defined reaction space [11]. |

Experimental Protocol: A Standard ML Workflow

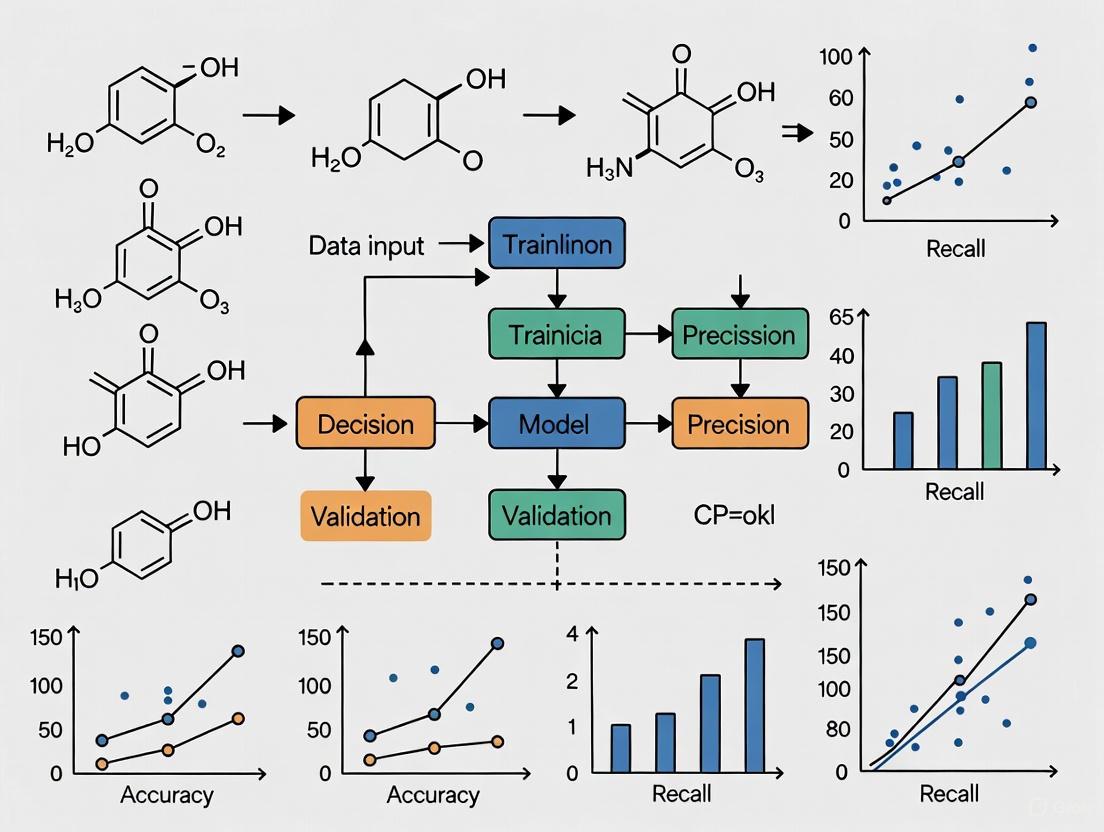

The diagram below outlines the standard workflow for a rigorous machine learning experiment in a chemical context [10].

Workflow for ML-Optimized Chemical Reaction

This diagram illustrates the iterative, closed-loop workflow for using machine learning to optimize chemical reactions, as implemented in platforms like Minerva [11].

High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) as the Data Engine for ML

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is the core advantage of using HTE over traditional OVAT (One-Variable-At-a-Time) methods for ML-driven research? HTE allows for the parallel exploration of a vast experimental space by running miniaturized reactions simultaneously. This approach generates the large, robust, and high-quality datasets required to train reliable Machine Learning (ML) models. Unlike OVAT methods, HTE can efficiently capture complex, non-linear interactions between multiple variables (e.g., solvents, catalysts, reagents, temperatures), which is essential for building accurate predictive models for reaction optimization [12].

Which ML models are best suited for the typically small datasets generated in initial HTE campaigns? For the small datasets common in early-stage research, Gaussian Process Regression (GPR) is particularly well-suited. GPR is a non-parametric, Bayesian approach that excels at interpolation and, crucially, provides uncertainty estimates for its predictions. This quantifiable uncertainty is invaluable for guiding subsequent experimental cycles, as it helps identify the most informative conditions to test next, thereby accelerating the optimization process [13].

How can spatial bias in microtiter plates (MTPs) impact my HTE results and ML model training? Spatial effects, such as uneven temperature distribution or inconsistent light irradiation across a microtiter plate, can introduce systematic errors in your data. For instance, edge wells might experience different conditions than center wells. If unaccounted for, these biases can lead to misleading correlations and degrade the performance of your ML models. It is critical to use randomized plate designs and employ equipment that minimizes these effects to ensure high-quality, reliable data [12].

Our HTE workflow for organic synthesis is complex. How can we ensure reproducibility? Reproducibility in HTE is challenged by factors like reagent evaporation at micro-volumes and the diverse physical properties of organic solvents. To ensure consistency:

- Standardize Protocols: Implement and adhere to standardized, automated protocols for liquid handling.

- Advanced Equipment: Utilize modern HTE equipment designed to handle air-sensitive reactions and a wide range of solvent properties.

- Plate Design: Carefully design plate layouts to account for and mitigate potential spatial biases [12].

What does FAIR data mean in the context of HTE for ML? FAIR stands for Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable. For HTE data, this means:

- Findable: Data is richly described with metadata (e.g., all reaction parameters, analytical methods) and assigned a persistent identifier.

- Accessible: Data is stored in a repository with a clear access protocol.

- Interoperable: Data is formatted using shared vocabularies and standards, allowing it to be integrated with other datasets.

- Reusable: Data is thoroughly documented to meet domain-relevant community standards. Adhering to FAIR principles is essential for maximizing the long-term value of HTE data, enabling effective collaboration, and building powerful, generalizable ML models [12].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Poor Correlation Between HTE Results and Scale-Up Batches

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Microscale Effects | Review data for inconsistencies between center and edge wells in MTPs, suggesting spatial bias. | Implement randomized block designs for MTPs. Use calibrated equipment that ensures uniform heating, mixing, and irradiation across all wells [12]. |

| Incomplete Reaction Parameter Space | Analyze the ML model's feature importance; if key physicochemical parameters are missing, the model may lack predictive power. | Expand HTE screening to include a wider range of continuous variables (e.g., pressure, stoichiometry) and use ML-guided design of experiments to fill knowledge gaps [13] [12]. |

| Inaccurate Analytical Methods | Cross-validate HTE analysis results (e.g., from HPLC/MS) with a subset of manually scaled-up reactions. | Optimize and validate analytical methods for the specific scale and matrix of the HTE platform. Use internal standards to improve quantification accuracy. |

Issue: ML Model Predictions are Inaccurate or Unreliable

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Insufficient or Low-Quality Data | Check the size and noise level of the dataset. Models trained on small or highly variable data will perform poorly. | Prioritize generating high-quality, reproducible data. Use active learning strategies, where the ML model itself suggests the most informative next experiments to perform, thereby improving data efficiency [13] [14]. |

| Incorrect Model Choice | Evaluate if the model's assumptions fit the data structure. Simple linear models may fail to capture complex reaction chemistry. | For small datasets, use GPR. For larger, more complex datasets, explore ensemble methods (like Random Forests) or neural networks. Ensure the model can handle the specific structure of your experimental data [13] [14]. |

| Inadequate Feature Representation | Test if the model performance improves when certain features (e.g., solvent polarity, catalyst structure) are removed or added. | Move beyond simple one-hot encodings. Incorporate meaningful physicochemical descriptors (e.g., σ‑donor strength, steric volume) and consider using learned representations from chemical language models [12]. |

Issue: High Rate of Failed Reactions in HTE Screening

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Material Incompatibility | Inspect for plate degradation, precipitate formation, or clogged dispensing tips. | Pre-test solvent and reagent compatibility with HTE materials. Implement pre-filtration of solutions or use plates with chemically resistant coatings [12]. |

| Liquid Handling Inaccuracy | Perform control experiments to dispense a known volume of a reference liquid and measure the mass/volume. | Regularly maintain and calibrate automated liquid handlers. Use liquid classes that are specifically optimized for the solvent's properties (e.g., viscosity, surface tension) [15]. |

| Air/Moisture Sensitivity | Compare the success rate of reactions run under an inert atmosphere versus ambient conditions. | Integrate gloveboxes or specialized inert atmosphere chambers into the HTE workflow for both plate preparation and storage [12]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: High-Throughput Screening of Reaction Conditions using Microtiter Plates

Objective: To systematically explore the effect of multiple reaction parameters (e.g., solvent, catalyst, ligand, base) on reaction yield and selectivity.

Materials:

- I.DOT Liquid Handler or equivalent automated dispensing system [15].

- 96-well or 384-well microtiter plates (MTPs).

- Stock solutions of substrates, catalysts, ligands, and bases in appropriate solvents.

- Inert atmosphere chamber (for air-sensitive chemistry).

Methodology:

- Plate Design: Create a randomized plate layout spreadsheet defining the volume of each component to be added to every well. This mitigates spatial bias [12].

- Dispensing: Using the automated liquid handler, dispense the specified volumes of solvents, substrates, catalysts, ligands, and bases into the respective wells according to the plate layout.

- Sealing and Reaction: Seal the MTP with a pressure-sensitive adhesive film. Place the plate on a thermomixer with orbital shaking to ensure mixing and heat to the desired reaction temperature for the set duration.

- Quenching and Dilution: After the reaction time, automatically add a quenching or dilution solvent to each well to stop the reaction and prepare the samples for analysis.

- Analysis: Analyze the reaction outcomes using high-throughput analytical techniques, such as:

- GC-MS/FID or UPLC-MS/PDA with automated sampling.

- Mass Spectrometry for rapid reaction monitoring [12].

Protocol 2: Acquiring Data for Process-Structure-Property (PSP) Modeling in Materials Science

Objective: To establish a quantitative relationship between manufacturing process parameters, resulting microstructures, and final mechanical properties of a material, such as additively manufactured Inconel 625 [13].

Materials:

- Laser Powder Directed Energy Deposition (LP-DED) system or equivalent additive manufacturing setup.

- Inconel 625 metallic powder.

- Equipment for sample preparation (mounting, polishing).

- Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) / Electron Backscatter Diffraction (EBSD).

- Small Punch Test (SPT) equipment.

Methodology:

- Sample Fabrication: Fabricate samples using the LP-DED process, systematically varying key process parameters (e.g., laser power, scan speed, hatch spacing) to create a library of samples with different process histories [13].

- Microstructural Characterization: Prepare metallographic samples and characterize the microstructure using SEM/EBSD to quantify features like grain size, phase distribution, and porosity.

- Mechanical Property Evaluation: Machine miniaturized specimens from the built samples and perform Small Punch Testing (SPT). Use established analysis protocols to estimate uniaxial tensile properties such as Yield Strength (YS) and Ultimate Tensile Strength (UTS) from the SPT load-displacement data [13].

- Data Integration: Compile the process parameters, quantified microstructural features, and estimated mechanical properties into a single structured dataset. This dataset serves as the foundation for training ML-based PSP models.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

| Item | Function in HTE/ML Workflow |

|---|---|

| Microtiter Plates (MTPs) | The foundational platform for running reactions in parallel. Available in 96, 384, and 1536-well formats to maximize throughput [12]. |

| Automated Liquid Handler | Precision robots for accurate and reproducible dispensing of microliter to nanoliter volumes of reagents and solvents, essential for assay assembly and replication [15]. |

| Bio-Layer Interferometry (BLI) | A label-free technique for high-throughput analysis of biomolecular interactions (e.g., antigen-antibody kinetics), generating rich kinetic data (kon, koff, KD) for ML models [16]. |

| Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) | Enables massive parallel sequencing of antibody repertoires or genetic outputs, providing the ultra-high-dimensional data needed to train predictive models in biologics design [16]. |

| Small Punch Test (SPT) Equipment | Allows for the estimation of traditional tensile properties (YS, UTS) from very small material samples, enabling the mechanical characterization of large libraries of materials produced by HTE [13]. |

| Differential Scanning Fluorimetry (DSF) | A high-throughput method for assessing protein or antibody stability by measuring thermal unfolding, a key developability property for therapeutic candidates [16]. |

HTE-ML Integration Workflows

In the optimization of chemical reactions for applications such as drug development, successfully navigating the complex landscape of reaction parameters is crucial. These parameters fall into two primary categories: categorical variables (distinct, non-numerical choices like catalysts, ligands, and solvents) and continuous variables (numerical quantities like temperature, concentration, and time). The interplay between these variables significantly influences key outcomes like yield and selectivity. Traditionally, chemists relied on the "one factor at a time" (OFAT) approach, which is often inefficient and can miss optimal conditions due to complex interactions between parameters [5]. Machine learning (ML) now offers powerful strategies to efficiently explore these high-dimensional spaces, accelerating the discovery of optimal reaction conditions [5] [11].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the fundamental difference between categorical and continuous variables in reaction optimization?

- Categorical Variables represent distinct classes or groups. They are qualitative and cannot be measured on a numerical scale. Examples in chemical reactions include the identity of the catalyst, ligand, solvent, and additives [5] [11]. The choice of categorical variable can create entirely different reaction landscapes, often leading to distinct and isolated optima [11].

- Continuous Variables are numerical parameters that can take on any value within a given range. They are quantitative and measurable. Examples include temperature, reaction time, catalyst loading, concentration, and pH [5] [11].

2. How does machine learning handle these two different types of variables?

ML models must convert all parameters into a numerical format. Continuous variables can be used directly. Categorical variables, however, require transformation using techniques like molecular descriptors or Morgan fingerprints to convert molecular structures into a numerical representation that the algorithm can process [11] [17]. The entire reaction condition space is often treated as a discrete combinatorial set of potential conditions, which allows for the automatic filtering of impractical combinations (e.g., a reaction temperature exceeding a solvent's boiling point) [11].

3. What are "global" versus "local" ML models in this context?

- Global Models are trained on large, diverse datasets covering many reaction types (e.g., from databases like Reaxys or the Open Reaction Database). They aim to suggest general reaction conditions for new reactions and are useful for computer-aided synthesis planning (CASP) [5].

- Local Models focus on a single reaction family or a specific transformation. They are typically trained on smaller, high-throughput experimentation (HTE) datasets and are designed to fine-tune specific parameters to improve yield and selectivity for that particular reaction [5]. Local models are often more practical for optimizing real-world chemical reactions [5].

4. Which ML algorithms are most effective for optimizing reaction conditions?

Studies have shown that for tasks like classifying the ideal coupling agent for amide coupling reactions, kernel methods and ensemble-based architectures (like Random Forest) perform significantly better than linear models or single decision trees [17]. For navigating complex optimization landscapes, Bayesian optimization is a powerful strategy. It uses a probabilistic model (like a Gaussian Process) to predict reaction outcomes and an acquisition function to intelligently select the next most promising experiments by balancing exploration and exploitation [11].

Troubleshooting Guides

Common Problem: Poor Reaction Yield

This is a frequent challenge where the desired product is not formed in sufficient quantity.

| Possible Cause | Recommendations |

|---|---|

| Suboptimal Categorical Variables | • Re-evaluate catalyst and ligand selection; even within a reaction family, the optimal pair can be highly substrate-specific [11].• Screen a diverse set of solvents, as the solvent environment can drastically impact reactivity [5]. |

| Incorrect Continuous Parameters | • Use ML-guided Bayesian optimization to efficiently search the space of continuous variables like temperature, concentration, and catalyst loading, rather than relying on OFAT [11].• Ensure reaction times are sufficient for completion. |

| Insufficient Purity of Inputs | • Re-purify starting materials to remove inhibitors. For DNA templates in PCR, this means removing residuals like salts, EDTA, or proteinase K [18]. |

Common Problem: Low Selectivity (Formation of Byproducts)

This occurs when the reaction proceeds via unwanted pathways, generating side products.

| Possible Cause | Recommendations |

|---|---|

| Non-ideal Ligand or Catalyst | The ligand often controls selectivity. Use ML classification models to identify the ligand class (e.g., phosphine, N-heterocyclic carbene) most associated with high selectivity for your reaction type [17]. |

| Inappropriate Temperature | • Optimize the temperature stepwise or using a gradient. A temperature that is too high may promote side reactions, while one that is too low may slow the desired reaction [18].• Let an ML model explore the interaction between temperature and solvent/catalyst choice [11]. |

| Incompatible Solvent System | The solvent can influence pathway selectivity. Explore different solvent classes (polar aprotic, non-polar, protic) to find one that favors the desired transition state [5]. |

Experimental Protocols for ML-Guided Optimization

Protocol 1: Initial Screening with HTE and Multi-Objective Bayesian Optimization

This protocol is designed for optimizing a reaction with multiple categorical and continuous parameters, balancing objectives like yield and selectivity [11].

- Define the Search Space: Compile a discrete set of all plausible reaction conditions, including catalysts, ligands, solvents, bases, additives, and ranges for temperature, concentration, and time. Apply chemical knowledge to filter out unsafe or impractical combinations.

- Initial Sampling: Use a quasi-random sampling method (e.g., Sobol sampling) to select an initial batch of experiments (e.g., one 96-well plate) that are diversely spread across the entire reaction condition space [11].

- Execute and Analyze: Run the initial batch of experiments using an automated HTE platform and analyze the outcomes (e.g., yield and selectivity via LCMS or NMR).

- ML Model Training & Selection: Train a Gaussian Process (GP) regressor on the collected experimental data to predict the outcomes and their uncertainties for all possible conditions in the search space [11].

- Select Next Experiments: Use a scalable multi-objective acquisition function (e.g., q-NParEgo or TS-HVI) to select the next batch of experiments. This function balances exploring uncertain regions of the search space and exploiting conditions that already show high performance [11].

- Iterate: Repeat steps 3-5 for multiple iterations, updating the model with new data each time, until performance converges or the experimental budget is exhausted.

Protocol 2: Building a Local Model for a Specific Reaction Family

This protocol uses existing data to train a model that can predict optimal conditions for new substrates within a known reaction class, such as amide couplings [17].

- Data Curation: Collect and standardize reaction data from sources like the Open Reaction Database (ORD) or in-house HTE. crucial data includes: substrates, catalysts, solvents, additives, temperatures, and yields [5] [17].

- Feature Engineering: Convert the categorical variables (molecules) into numerical features. Use Morgan Fingerprints or other molecular descriptors, particularly focusing on the features around the reactive functional groups, as these have been shown to boost model predictivity [17].

- Model Training and Validation: Train multiple types of models (e.g., Random Forest, kernel methods, neural networks) to perform either regression (predicting yield) or classification (predicting the ideal coupling agent category). Validate model performance on a held-out test set [17].

- Model Deployment and Validation: Use the best-performing model to recommend conditions for novel substrate pairs. Validate the top recommendations experimentally in the lab [17].

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the iterative workflow for ML-guided reaction optimization.

Key Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential materials and computational resources used in advanced reaction optimization campaigns.

| Reagent / Resource | Function & Explanation |

|---|---|

| High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) Platforms | Automated robotic systems that enable highly parallel execution of numerous miniaturized reactions. This allows for efficient exploration of many condition combinations, making data collection for ML models feasible [5] [11]. |

| Open Reaction Database (ORD) | An open-source initiative to collect and standardize chemical synthesis data. It serves as a crucial resource for acquiring diverse, machine-readable data to train global ML models [5]. |

| Molecular Descriptors (e.g., Morgan Fingerprints) | Numerical representations of molecular structures that allow ML algorithms to process categorical variables like solvents and ligands. They encode molecular features critical for predicting reactivity [17]. |

| Bayesian Optimization Software (e.g., Minerva) | A specialized ML framework for highly parallel, multi-objective reaction optimization. It is designed to handle large batch sizes (e.g., 96-well) and high-dimensional search spaces present in real-world labs [11]. |

| Ligand Libraries | Diverse collections of phosphine, N-heterocyclic carbene, and other ligand classes. The ligand is often the most critical categorical variable influencing both catalytic activity and selectivity [11]. |

| Earth-Abundant Metal Catalysts (e.g., Nickel) | Lower-cost, greener alternatives to precious metal catalysts like palladium. A key goal in modern process chemistry is to optimize reactions using these more sustainable metals [11]. |

FAQs: Machine Learning for Reaction Optimization

FAQ 1: What are the main types of ML models for reaction optimization and when should I use them?

ML models for reaction optimization are broadly categorized into global and local models, each with distinct applications [5].

Global Models

- Purpose: Predict experimental conditions for a wide range of reaction types.

- Data Requirement: Trained on large, diverse reaction databases (e.g., millions of reactions) [5].

- Best For: Computer-aided synthesis planning (CASP) and initial condition recommendation for novel reactions where historical data is sparse [5].

Local Models

- Purpose: Fine-tune specific parameters (e.g., concentration, temperature) for a single reaction family to maximize yield or selectivity.

- Data Requirement: Trained on smaller, high-quality datasets focused on one reaction type, often generated via High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) [5].

- Best For: Optimizing a specific reaction of interest, especially when combined with Bayesian Optimization to navigate complex parameter spaces efficiently [5] [11].

FAQ 2: My ML model's predictions are inaccurate. What could be wrong?

Inaccurate predictions often stem from underlying data issues. Common challenges and solutions are summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Troubleshooting Guide for ML Model Performance

| Problem | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Poor Prediction Accuracy | Low data quality or insufficient data volume; selection bias in training data [19] [5]. | Prioritize data quality: use standardized, high-throughput experimentation (HTE) data that includes failed experiments (zero yields) to avoid bias [5]. |

| Non-representative molecular descriptors [19]. | Improve feature engineering: use physical-chemistry-informed descriptors or advanced fingerprint methods (e.g., ECFP) [19]. | |

| Failure to Find Optimal Conditions | Inefficient search strategy in a high-dimensional space [11]. | Implement advanced Bayesian Optimization: use acquisition functions like q-NEHVI that handle multiple objectives (e.g., yield, cost) and large parallel batches [11]. |

| Inability to Generate Novel Catalysts | Model constrained to known chemical libraries [20]. | Use generative models: employ reaction-conditioned generative models (e.g., CatDRX) to design new catalyst structures beyond existing libraries [20]. |

FAQ 3: How can I optimize a reaction for multiple objectives, like both yield and selectivity?

Multi-objective optimization is a key strength of modern ML frameworks. The work flow involves:

- Define Objectives: Clearly specify the targets (e.g., maximize yield, maximize selectivity, minimize cost) [11].

- Use Specialized Algorithms: Employ multi-objective Bayesian Optimization. Algorithms like q-NParEgo or q-Noisy Expected Hypervolume Improvement (q-NEHVI) are designed to handle multiple, competing goals efficiently [11].

- Evaluate with Hypervolume: Use the hypervolume metric to assess performance. This metric measures the volume of the objective space covered by the identified conditions, balancing convergence to the true optimum with the diversity of solutions [11].

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol: ML-Guided High-Throughput Optimization Campaign

This protocol is adapted from the "Minerva" framework for highly parallel reaction optimization [11].

Objective: To identify reaction conditions that maximize yield and selectivity for a given transformation within a 96-well HTE plate setup.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Define the Search Space:

- Compile a discrete set of plausible reaction conditions, including categorical variables (catalyst, ligand, solvent, additive) and continuous variables (temperature, concentration) [11].

- Apply chemical knowledge filters to automatically exclude unsafe or impractical combinations (e.g., temperatures exceeding solvent boiling points) [11].

Initial Batch Selection:

- Use Sobol sampling to select the first batch of 96 experiments. This quasi-random method ensures the initial experiments are spread diversely across the entire reaction condition space to maximize information gain [11].

Execute Experiments & Analyze:

- Run the selected reactions using an automated HTE platform.

- Measure outcomes (e.g., yield and selectivity via Area Percent or quantitative NMR).

Machine Learning Optimization Cycle:

- Train Model: Train a Gaussian Process (GP) regressor on all collected data to predict reaction outcomes and their uncertainties for all possible conditions in the search space [11].

- Select Next Batch: Use a multi-objective acquisition function (e.g., q-NEHVI) to select the next batch of 96 experiments. This function balances exploring uncertain regions of the search space with exploiting conditions that already show high performance [11].

- Iterate: Repeat steps 3 and 4 for several iterations until performance converges, improvement stagnates, or the experimental budget is exhausted.

The following workflow diagram illustrates this iterative optimization cycle.

Protocol: Generative Design of Novel Catalysts

This protocol outlines the use of a generative model for catalyst design, as demonstrated by the CatDRX framework [20].

Objective: To generate novel, effective catalyst structures for a specific chemical reaction.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Model Input Preparation:

- Provide the reaction components as a condition: reactants, reagents, products, and reaction properties (e.g., time) [20].

- The model uses a joint architecture to learn embeddings for both the catalyst and the reaction conditions.

Catalyst Generation & Prediction:

- A Conditional Variational Autoencoder (CVAE) samples from a learned latent space of catalysts and reactions [20].

- The sampled latent vector, combined with the condition embedding, is used by a decoder to generate novel catalyst molecules.

- A predictor module uses the same information to estimate the catalytic performance (e.g., yield) of the generated catalyst [20].

Candidate Validation:

- Filter generated catalysts using background chemical knowledge and synthesizability checks.

- Validate promising candidates using computational chemistry tools (e.g., DFT calculations) before proceeding to experimental testing [20].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Components for ML-Driven Reaction Optimization

| Reagent / Material | Function in Optimization | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Non-Precious Metal Catalysts (e.g., Ni) | Catalyze key cross-coupling reactions (e.g., Suzuki, Buchwald-Hartwig) as lower-cost, earth-abundant alternatives to Pd [11]. | Can exhibit unexpected reactivity, requiring robust ML models to navigate complex landscapes [11]. |

| Ligand Libraries | Modulate catalyst activity, selectivity, and stability. A key categorical variable in optimization searches [11]. | Diversity of the ligand library is critical for exploring a wide chemical space and finding optimal performance [5]. |

| Solvent Sets | Affect reaction rate, mechanism, and solubility. A major factor in reaction outcome optimization [5]. | Selection should be guided by pharmaceutical industry guidelines for greener and safer alternatives [11]. |

| High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) Platforms | Enable highly parallel execution of reactions (e.g., in 96-well plates), generating the large, consistent datasets needed for ML [5] [11]. | Integration with robotic liquid handlers and automated analysis is essential for scalability and data quality. |

| Molecular Descriptors (e.g., ECFP4, SOAP) | Numerical representations of molecules (catalysts, ligands, solvents) that serve as input features for ML models [19] [20]. | The choice of descriptor significantly impacts model performance and its ability to capture structure-property relationships [19]. |

ML Algorithms in Action: Methodologies and Real-World Pharmaceutical Applications

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

FAQ: Core Concepts

Q1: What is the primary challenge that Bayesian Optimization addresses in experimental optimization?

Bayesian Optimization (BO) is designed for global optimization of black-box functions that are expensive to evaluate. It does not assume any functional form for the objective, making it ideal for scenarios where you have a complex, costly process—like a chemical reaction—and a limited budget for experiments. Its primary strength is its sequential strategy for intelligently choosing which experiment to run next by balancing the exploration of unknown parameter spaces with the exploitation of known promising regions [21] [22].

Q2: How does the "acquisition function" manage the trade-off between exploration and exploitation?

The acquisition function is a utility function that uses the surrogate model's predictions (mean) and uncertainty (variance) to quantify how "interesting" or "valuable" it is to evaluate a candidate point. It automatically enforces the trade-off [22]:

- Exploitation guides the search towards points where the surrogate model predicts a high value (good performance).

- Exploration guides the search towards points where the surrogate model's uncertainty is high. By maximizing the acquisition function at each iteration, BO selects the next experiment that offers the best balance between these two competing goals [23].

Q3: Why is a Gaussian Process typically chosen as the surrogate model?

The Gaussian Process (GP) is a common choice for the surrogate model in BO for two key reasons [22] [23]:

- Flexibility: It is a non-parametric model that can represent a wide variety of complex, non-linear functions without requiring the user to specify a fixed form.

- Uncertainty Quantification: It provides a probabilistic prediction at any unobserved point, giving both an expected value (mean) and a measure of uncertainty (variance). This uncertainty estimate is crucial for the acquisition function to balance exploration and exploitation.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Issues

Q1: My optimization process seems to get stuck in a local optimum. How can I encourage more exploration?

Problem: The algorithm is over-exploiting a small region and failing to discover a potentially better, global optimum.

Solutions:

- Switch your Acquisition Function: If you are using Probability of Improvement (PI), consider switching to Expected Improvement (EI) or Upper Confidence Bound (UCB). EI generally provides a better-balanced trade-off [22] [23].

- Adjust Acquisition Hyperparameters: For the PI function, you can increase the

ϵparameter to force more exploration. For UCB, increase the weight (κ) on the standard deviation term [23]. - Review Initial Design: Ensure your initial set of points (e.g., from Latin Hypercube Sampling) is sufficiently large and space-filling to provide a good initial model of the entire domain [22].

Q2: The optimization is taking too long, and fitting the Gaussian Process model is the bottleneck. What are my options?

Problem: The computational cost of updating the GP surrogate model becomes prohibitive as the number of observations grows.

Solutions:

- Use a Different Surrogate Model: For higher-dimensional problems or larger datasets, consider using a Bayesian Neural Network or a model based on the Parzen-Tree Estimator (TPE), which can be less computationally expensive than a standard GP [21].

- Optimize the Acquisition Function Efficiently: Instead of a fine-grained global optimization, use a multi-start strategy with a faster optimizer (e.g., L-BFGS-B) or a quasi-Monte Carlo method to find the maximum of the acquisition function [21].

- Implement Batched Evaluations: Use a parallelized acquisition function (e.g., q-EI) to propose a batch of experiments at once, which can then be evaluated in parallel, reducing the total experimental time [22].

Q3: My experimental measurements are noisy. How can I make the Bayesian Optimization process more robust?

Problem: The objective function evaluations are not deterministic, which can mislead the surrogate model and derail the optimization.

Solutions:

- Use a Noisy GP Model: Explicitly configure your Gaussian Process to account for noise by including a noise term (often referred to as a "nugget" or Gaussian noise kernel) in its specification. This prevents the model from needing to interpolate the noisy data points exactly, leading to a smoother and more robust surrogate [22] [21].

- Choose a Noise-Tolerant Acquisition Function: Ensure your acquisition function, such as Expected Improvement, is the version designed to handle noisy observations [22].

Q4: How do I handle the optimization of multiple objectives simultaneously, such as maximizing yield while minimizing cost?

Problem: The goal is to find a set of Pareto-optimal solutions that represent the best trade-offs between two or more competing objectives.

Solutions:

- Adopt Multi-Objective Bayesian Optimization (MOBO): This framework extends BO to multiple objectives. The surrogate modeling and acquisition function are adapted to handle multiple outputs.

- Use a Multi-Objective Acquisition Function: A common approach is to use the Expected Hypervolume Improvement (EHVI), which measures the expected improvement in the total volume of the objective space dominated by the Pareto front [24].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Detailed Methodology: Hyperparameter Tuning for a Predictive Model

This protocol is adapted from a study that used a Deep Learning-Bayesian Optimization (DL-BO) model for slope stability classification, demonstrating a real-world application of BO [25].

1. Problem Formulation:

- Objective: To classify slopes as stable or unstable.

- Black-Box Function: The validation accuracy of a deep learning model (e.g., LSTM) on a held-out test set.

- Parameters to Optimize: Deep learning hyperparameters (e.g., learning rate, number of layers, dropout rate, number of epochs).

2. Experimental Setup:

- Data: 575 real-life slope samples, split 85:15 into training and testing sets. Use 5-stratified k-fold cross-validation for robust evaluation [25].

- Surrogate Model: Gaussian Process with a Matern kernel.

- Acquisition Function: Expected Improvement (EI).

3. Optimization Procedure:

a. Initialization: Generate an initial design of 10-20 random points in the hyperparameter space.

b. Iteration Loop:

i. For each set of hyperparameters in the current data, train the LSTM model and evaluate its accuracy.

ii. Update the GP surrogate model with all {hyperparameters, accuracy} pairs collected so far.

iii. Find the hyperparameter set that maximizes the Expected Improvement acquisition function.

iv. Train the LSTM model with this new hyperparameter set, obtain its accuracy, and add the result to the data set.

c. Termination: Repeat the loop for a fixed number of iterations (e.g., 50-100) or until convergence (e.g., no significant improvement over several iterations).

4. Evaluation:

- The best-performing hyperparameters are selected based on the highest validation accuracy found.

- The final model is evaluated on the held-out test set, reporting accuracy, AUC, precision, recall, and F1-score [25].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Different Deep Learning Models Tuned with Bayesian Optimization [25]

| Model | Test Accuracy | Area Under the ROC Curve (AUC) |

|---|---|---|

| RNN-BO | 81.6% | 89.3% |

| LSTM-BO | 85.1% | 89.8% |

| Bi-LSTM-BO | 87.4% | 95.1% |

| Attention-LSTM-BO | 86.2% | 89.6% |

Table 2: Comparison of Common Acquisition Functions [22] [23] [21]

| Acquisition Function | Key Principle | Best For |

|---|---|---|

| Probability of Improvement (PI) | Maximizes the chance of improving over the current best value. | Simple problems, but can get stuck in local optima without careful tuning of its ϵ parameter. |

| Expected Improvement (EI) | Maximizes the expected amount of improvement over the current best. | General-purpose use; well-balanced trade-off; analytic form available. |

| Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) | Maximizes the sum of the predicted mean plus a weighted standard deviation. | Explicit and direct control over exploration/exploitation via the κ parameter. |

Workflow and Relationship Visualizations

Bayesian Optimization Core Loop

Exploration vs. Exploitation Trade-off

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Components for a Bayesian Optimization Framework

| Item / Tool | Function / Purpose |

|---|---|

| Gaussian Process (GP) | The core probabilistic surrogate model that approximates the expensive black-box function and provides uncertainty estimates for every point in the search space [22] [21]. |

| Expected Improvement (EI) | An acquisition function that recommends the next experiment by calculating the expected value of improving upon the current best observation, offering a robust balance between exploration and exploitation [22] [21]. |

Python bayesian-optimization Package |

A widely used Python library (v3.1.0+) that provides a ready-to-use implementation of BO, making it accessible for integrating into drug discovery and reaction optimization pipelines [26]. |

| Multi-Objective Acquisition Function (EHVI) | For multi-objective problems (e.g., maximize yield, minimize impurities), this function guides the search towards parameters that improve the Pareto front of optimal trade-offs [24]. |

| Tree-structured Parzen Estimator (TPE) | An alternative surrogate model to GP, often more efficient in high dimensions or for large initial datasets, useful when GP fitting becomes a computational bottleneck [21]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is multi-objective optimization, and why is it important in reaction development? Multi-objective optimization involves solving problems with more than one objective function to be optimized simultaneously [27]. In reaction development, this means finding conditions that balance competing goals like high yield, high selectivity, and low cost, as improving one objective often comes at the expense of another [27] [11]. The solution is not a single "best" condition but a set of optimal trade-offs known as the Pareto front [27].

Q2: How does machine learning, specifically Bayesian optimization, help in this process? Machine learning, particularly Bayesian optimization, uses experimental data to build a model that predicts reaction outcomes and their uncertainties for a vast space of possible conditions [11]. It employs an "acquisition function" to intelligently select the next batch of experiments by balancing the exploration of unknown regions and the exploitation of promising areas, thereby finding high-performing conditions with fewer experiments than traditional methods [11].

Q3: My ML model isn't finding better conditions. What could be wrong? This is a common troubleshooting issue. The table below summarizes potential causes and solutions.

| Problem Area | Specific Issue | Potential Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Initial Data | Initial sampling is too small or not diverse. | Use algorithmic quasi-random sampling (e.g., Sobol sampling) to ensure broad initial coverage of the reaction condition space [11]. |

| Search Space | The defined space of plausible reactions is too narrow. | Review and expand the set of considered parameters (e.g., solvents, ligands, additives) based on chemical knowledge, while automatically filtering unsafe combinations [11]. |

| Acquisition Function | The algorithm gets stuck in a local optimum. | Adjust the exploration-exploitation balance in the acquisition function to encourage more exploration [11]. |

| Objective Scalarization | Competing objectives are poorly balanced. | Use specialized multi-objective acquisition functions like q-NParEgo or q-NEHVI instead of combining objectives into a single score [11]. |

Q4: How can I handle optimizing multiple objectives at once, like yield and cost? For multiple competing objectives, use acquisition functions designed for multi-objective optimization, such as:

- q-NParEgo

- Thompson Sampling with Hypervolume Improvement (TS-HVI)

- q-Noisy Expected Hypervolume Improvement (q-NEHVI) [11] These functions evaluate performance based on the hypervolume of the objective space, which measures both the convergence towards optimal values and the diversity of the solutions found [11].

Q5: Can this be applied to industrial process development with tight timelines? Yes. ML-driven optimization integrated with high-throughput experimentation (HTE) has been successfully deployed in pharmaceutical process development. This approach has identified conditions achieving >95% yield and selectivity for challenging reactions like Ni-catalyzed Suzuki and Pd-catalyzed Buchwald-Hartwig couplings, significantly accelerating development timelines from months to weeks [11].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Pitfalls

Problem: High-Dimensional Search Spaces Are Too Large to Explore

- Challenge: The number of possible combinations of reagents, solvents, catalysts, and temperatures multiplies rapidly, making exhaustive screening impossible [11].

- Solution: Frame the reaction condition space as a discrete combinatorial set of all plausible conditions. Leverage the ML algorithm to efficiently navigate this high-dimensional space without testing every combination [11].

Problem: Algorithm Performance is Slow with Large Parallel Batches

- Challenge: Some multi-objective acquisition functions become computationally slow with large batch sizes (e.g., 96-well plates) [11].

- Solution: Implement scalable acquisition functions like q-NParEgo, TS-HVI, or q-NEHVI, which are designed to handle the computational load of highly parallel experimentation [11].

Problem: Dealing with Noisy or Unreliable Experimental Data

- Challenge: Experimental variability ("chemical noise") can mislead the optimization model [11].

- Solution: Choose optimization workflows, like those using Gaussian Process regressors, that are robust to noise. The inherent uncertainty quantification in these models helps mitigate the impact of sporadic poor results [11].

Experimental Protocol: A Standard ML-Driven Optimization Workflow

The following workflow is adapted from the Minerva framework for a 96-well HTE campaign [11].

1. Define the Reaction Condition Space

- Compile a discrete set of all plausible reaction conditions, including categorical (e.g., ligand, solvent) and continuous (e.g., temperature, concentration) variables.

- Use chemical knowledge to automatically filter out impractical or unsafe combinations (e.g., temperatures exceeding solvent boiling points) [11].

2. Initial Experimental Batch via Sobol Sampling

- Select the first batch of experiments using Sobol sampling. This quasi-random method ensures the initial conditions are widely spread across the entire search space, maximizing the chance of finding informative regions [11].

3. Model Training and Iteration

- Train a Model: Use the collected experimental data (e.g., yields, selectivity) to train a Gaussian Process (GP) regressor. This model will predict outcomes and their uncertainty for all other conditions in the search space [11].

- Select Next Experiments: An acquisition function uses the GP's predictions to score all unexplored conditions and select the next most promising batch of experiments [11].

- Run Experiments and Update: Conduct the newly selected experiments, add the data to the training set, and retrain the model. Repeat this process until objectives are met or the experimental budget is exhausted.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists common components in a catalyst screening kit for cross-coupling reactions and their functions.

| Reagent / Material | Function in Optimization |

|---|---|

| Ligand Library | Modifies the catalyst's properties (activity, selectivity, stability); a diverse library is crucial for exploring the reaction space [11]. |

| Base Library | Facilitates the catalytic cycle; different bases can dramatically impact yield and selectivity [11]. |

| Solvent Library | Affects reaction rate, solubility, and mechanism; a key categorical variable to optimize [11]. |

| Earth-Abundant Metal Catalysts (e.g., Ni) | Lower-cost, greener alternatives to precious metals like Pd; often a target for optimization in process chemistry [11]. |

| Automated HTE Platform | Enables highly parallel execution of reactions (e.g., in 96-well plates), providing the large, consistent dataset required for ML algorithms [11]. |

Workflow and Concept Visualizations

ML-Optimization Workflow

Pareto Front Concept

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents and materials essential for implementing the Minerva framework for reaction optimization, based on the case studies conducted [11].

| Reagent Category | Specific Example | Function in Reaction Optimization |

|---|---|---|

| Non-Precious Metal Catalyst | Nickel-based catalysts | Serves as a lower-cost, earth-abundant alternative to precious metal catalysts like Palladium for Suzuki and Buchwald-Hartwig couplings [11]. |

| Ligands | Not specified (categorical variable) | Significantly influences reaction outcome and selectivity; a key categorical parameter for the ML algorithm to explore [11]. |

| Solvents | Not specified (categorical variable) | A major reaction parameter; optimized based on pharmaceutical guidelines for safety and environmental considerations [11]. |

| Additives | Not specified (categorical variable) | Can substantially impact reaction yield and landscape; treated as a key categorical variable for algorithmic exploration [11]. |

| Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API) Intermediates | Substrates for Suzuki and Buchwald-Hartwig reactions | The target molecules for synthesis; optimal conditions are often substrate-specific [11]. |

Experimental Protocols & Data Presentation

Core Optimization Workflow Methodology

The Minerva framework employs a structured, iterative protocol for high-throughput reaction optimization [11].

- Reaction Space Definition: A discrete combinatorial set of plausible reaction conditions is defined by the chemist. This includes categorical variables (ligands, solvents, additives) and continuous variables (temperature, catalyst loading). The space automatically filters out impractical or unsafe condition combinations [11].

- Initial Experiment Selection: The workflow initiates with quasi-random Sobol sampling to select the first batch of experiments. This ensures the initial experimental configurations are diversely spread across the entire reaction condition space for maximum coverage [11].

- ML Model Training & Prediction: After obtaining experimental data from a batch, a Gaussian Process (GP) regressor is trained to predict reaction outcomes (e.g., yield, selectivity) and their associated uncertainties for all possible condition combinations in the predefined space [11].

- Batch Selection via Acquisition Function: A multi-objective acquisition function evaluates all reaction conditions. It balances the exploration of uncertain regions of the search space with the exploitation of known promising areas to select the next most informative batch of experiments [11].

- Iteration: Steps 3 and 4 are repeated for multiple cycles. The chemist can integrate evolving insights, fine-tune the strategy, and terminate the campaign upon convergence, stagnation, or exhaustion of the experimental budget [11].

Key Experimental Results and Performance Metrics

The Minerva framework was validated through several experimental campaigns. The table below summarizes the key quantitative outcomes.

| Reaction Type | Optimization Challenge | Key Results with Minerva | Comparison to Traditional Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ni-catalyzed Suzuki Reaction | Navigate a complex landscape with unexpected chemical reactivity [11]. | Identified conditions with 76% AP yield and 92% selectivity [11]. | Chemist-designed HTE plates failed to find successful reaction conditions [11]. |

| Ni-catalyzed Suzuki Coupling (API Synthesis) | Identify high-performing, scalable process conditions [11]. | Multiple conditions achieved >95% AP yield and selectivity [11]. | Led to improved process conditions at scale in 4 weeks versus a previous 6-month development campaign [11]. |

| Pd-catalyzed Buchwald-Hartwig Reaction (API Synthesis) | Optimize multiple objectives for a pharmaceutical process [11]. | Multiple conditions achieved >95% AP yield and selectivity [11]. | Significantly accelerated process development timelines [11]. |

Multi-Objective Acquisition Functions

For the highly parallel optimization of multiple objectives (e.g., maximizing yield while maximizing selectivity), Minerva implements several scalable acquisition functions to handle large batch sizes [11].

| Acquisition Function | Key Characteristic | Suitability for HTE |

|---|---|---|

| q-NParEgo | A scalable multi-objective acquisition function based on random scalarizations [11]. | Designed to handle the computational load of large batch sizes (e.g., 96-well plates) [11]. |

| TS-HVI | Thompson Sampling with Hypervolume Improvement; combines random sampling with hypervolume metrics [11]. | Offers a scalable alternative for parallel batch selection [11]. |

| q-NEHVI | q-Noisy Expected Hypervolume Improvement; a state-of-the-art method for noisy observations [11]. | While powerful, its computational complexity can challenge the largest batch sizes [11]. |

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Our optimization campaign seems to be stuck in a local optimum, failing to improve after several iterations. What steps can we take?

A1: This is a common challenge. The Minerva framework incorporates strategies to address this:

- Review Acquisition Function Balance: The acquisition function balances exploration (trying new regions) and exploitation (refining known good regions). If stuck, you can manually adjust this balance towards more exploration in subsequent iterations to help the algorithm escape local optima [11].

- Leverage ML-Guided Reinitialization: Inspired by metaheuristic algorithms like α-PSO, a strategy to combat stagnation is to reinitialize a portion of the particle swarm (experimental batch) from stagnant local optima to more promising regions of the reaction space based on ML predictions [28]. You can review the batch suggestions and consider incorporating more diverse conditions manually.

Q2: How does Minerva handle the "curse of dimensionality" when searching high-dimensional spaces with many categorical variables like ligands and solvents?

A2: Minerva is specifically designed for this challenge.

- Discrete Combinatorial Search Space: The framework represents the reaction condition space as a discrete set of plausible conditions, which avoids the infinite complexity of a purely continuous high-dimensional space [11].

- Efficient Initial Sampling: It uses quasi-random Sobol sampling for the initial batch to ensure broad coverage of this complex space, increasing the chance of discovering informative regions early on [11].

- Algorithmic Exploration: The ML model is particularly focused on exploring categorical variables, as they are known to create distinct optima. By efficiently navigating these, the algorithm can identify promising regions for further refinement of continuous parameters [11].

Q3: What are the computational limitations when scaling to very large batch sizes (e.g., 96-well plates) with multiple objectives?

A3: Computational scaling is a key consideration.

- Scalable Acquisition Functions: Traditional multi-objective acquisition functions like q-EHVI can have exponential complexity with batch size. Minerva implements more scalable functions like q-NParEgo and TS-HVI specifically to handle the computational load of large batches (24, 48, 96) over multiple iterations [11].

- Performance Benchmarking: The framework's performance has been benchmarked using emulated virtual datasets for these standard HTE batch sizes, confirming robust operation [11].

Q4: We encountered an error stating a command is "too long to execute" when using the software. What is the cause?

A4: This error appears to be related to a different software platform also named "Minerva" used for metabolic pathway visualization [29]. For the machine learning framework for reaction optimization discussed here, ensure you are using the correct code repository and that your input data and configuration files adhere to the required formats and size limits specified in its documentation [11] [30].

Q5: How does Minerva's performance compare to other optimization algorithms like Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO)?

A5: Benchmarking studies show that advanced ML methods like those in Minerva are highly competitive.

- A novel algorithm, α-PSO, which integrates ML guidance into a canonical PSO framework, has demonstrated performance competitive with state-of-the-art Bayesian optimization (as used in Minerva) [28].

- In some prospective experimental campaigns, α-PSO identified optimal conditions more rapidly than Bayesian optimization, highlighting the ongoing evolution of optimization algorithms [28]. The choice of algorithm may depend on the specific reaction landscape and the desired balance between performance and interpretability.

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Poor Model Performance in New Reaction Campaign

- Problem: The SeMOpt algorithm fails to identify improved reaction conditions, showing slow convergence or performance worse than standard optimizers.

- Possible Cause A: Insufficient relevance between the selected historical source data and the new target reaction.

- Solution: Re-evaluate the source data. Use domain knowledge to select historical campaigns with similar reaction mechanisms, functional group tolerances, or catalyst systems. The source data should be a focused set of reactions specifically relevant to the new goal [31].

- Possible Cause B: The "Rule of Five" principles for data set quality are not met.

- Solution: Audit your source data set. Ensure it contains a minimum of 500 entries, covers at least 10 different drugs or core structures, and includes all critical process parameters [32].

- Possible Cause C: Inadequate molecular representations for drugs and excipients.

- Solution: Shift from simple molecular fingerprints to more nuanced representations that capture steric and electronic properties critical for reactivity [32].

Issue 2: Algorithm Failure when No Prior Successful Data Exists

- Problem: The novel reaction campaign has no successful historical data, only negative results, causing the transfer learning to stall.

- Solution: Leverage SeMOpt's ability to learn from related, but not identical, transformations. Utilize multiple small source data sets that inform different aspects of the reaction, such as viable catalysts from one source and mechanistic concepts from another, mimicking a chemist's approach [31].

Issue 3: High Variance in Optimization Results

- Problem: Repeated optimization campaigns for the same target reaction yield widely different results.

- Possible Cause: The compound acquisition function is overly sensitive to the initial random seed or noisy historical data.

- Solution: Implement a heterogeneity-aware approach. Ensure the model architecture accounts for varying data quality and uncertainty across different source domains [33].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the minimum amount of historical data required to use SeMOpt effectively? While more data is generally better, SeMOpt's meta-/few-shot learning framework is designed for efficiency. Meaningful transfer can be initiated with a focused source data set containing as few as 100 relevant data points, though performance improves significantly with larger, high-quality datasets that meet the "Rule of Five" criteria [32] [31].

Q2: Can SeMOpt be applied to reaction types not present in our historical database? Yes, but with a modified strategy. For entirely new reaction types, the initial source data should consist of reactions that share underlying chemical principles (e.g., similar catalytic cycles or intermediate states). The algorithm will rely more heavily on its meta-learning capabilities to generalize from these analogous systems [31].