Mastering Ionization Efficiency in LC-MS: From Fundamental Principles to Advanced Quantification Strategies

This article provides a comprehensive examination of the factors influencing ionization efficiency in Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS), a cornerstone technique in bioanalysis, drug development, and clinical diagnostics.

Mastering Ionization Efficiency in LC-MS: From Fundamental Principles to Advanced Quantification Strategies

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive examination of the factors influencing ionization efficiency in Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS), a cornerstone technique in bioanalysis, drug development, and clinical diagnostics. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, we explore the foundational principles of electrospray ionization, detailing how analyte properties and mobile phase composition dictate signal response. The scope extends to practical methodologies for mitigating pervasive challenges like ion suppression, advanced optimization protocols for instrument parameters, and rigorous validation frameworks as per international guidelines. Furthermore, we investigate cutting-edge strategies, including machine learning and non-targeted quantification, that are pushing the boundaries of quantitative bioanalysis, ensuring robust, sensitive, and reliable results.

The Core Principles: Unraveling the Fundamentals of Ionization in LC-MS

In liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS), the ionization source serves as the critical interface, transforming neutral analyte molecules from the liquid chromatograph into gas-phase ions for mass analysis. The selection and optimization of this ionization process are paramount, as it fundamentally dictates the sensitivity, scope, and reliability of the entire analytical method. Within the context of factors affecting ionization efficiency in LC-MS research, two atmospheric pressure ionization (API) techniques have become foundational: Electrospray Ionization (ESI) and Atmospheric Pressure Chemical Ionization (APCI). A third technique, Atmospheric Pressure Photoionization (APPI), serves as an important tool for specific applications. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical guide to the core mechanisms, performance characteristics, and experimental considerations of these techniques, equipping researchers and drug development professionals with the knowledge to optimize their analytical workflows.

Core Ionization Mechanisms

Electrospray Ionization (ESI): Liquid-Phase Ionization

ESI is a soft ionization technique ideal for polar and thermally labile compounds, including large biomolecules [1] [2]. Its mechanism involves multiple stages:

- Nebulization and Charged Droplet Formation: The sample solution is sprayed through a narrow capillary (needle) to which a high voltage (±3 to 5 kV) is applied. This creates a fine mist of charged droplets [2].

- Droplet Shrinking and Coulomb Fission: As the solvent evaporates, assisted by a nebulizing gas and heat, the charged droplets shrink. The increasing charge density on the droplet surface eventually overcomes the liquid's surface tension (the Rayleigh limit), causing the droplet to disintegrate into smaller, progeny droplets [2].

- Ion Emission: This cycle of evaporation and fission repeats until the droplets are sufficiently small that individual, desolvated analyte ions are emitted into the gas phase (as described by the Ion Evaporation Model) [2].

A key characteristic of ESI is its ability to generate multiply charged ions, particularly for analytes with multiple charge-accepting sites, such as proteins. This reduces the mass-to-charge ratio ((m/z)), enabling the analysis of macromolecules beyond the nominal mass range of the mass analyzer [2]. The following diagram illustrates the ESI process for positive ion formation.

ESI Process for Positive Ions

Atmospheric Pressure Chemical Ionization (APCI): Gas-Phase Ionization

APCI is also a soft ionization technique but is better suited for less polar and thermally stable compounds with low to medium molecular weights (typically < 1500 Da) [1] [3]. Unlike ESI, ionization in APCI occurs in the gas phase after the analyte is vaporized. The mechanism proceeds as follows:

- Nebulization and Vaporization: The sample solution is nebulized into a fine spray and immediately vaporized in a heated tube (typically 350–500 °C) [2] [3].

- Corona Discharge and Reagent Ion Formation: A corona discharge needle (with a current of 2–5 µA) emits electrons that ionize the nebulizer gas (typically N₂) and solvent vapor. This initiates a cascade of ion-molecule reactions, ultimately leading to the formation of stable reagent ions, such as hydronium ion clusters H⁺(H₂O)ₙ when water is the primary solvent [3].

- Chemical Ionization of Analyte: The gaseous analyte molecules (M) are ionized via proton transfer reactions with the reagent ions. In positive mode, this produces protonated molecules [M+H]⁺. Deprotonation or anion attachment can occur in negative mode [2] [3].

APCI generally produces singly charged ions and is less prone to severe matrix effects compared to ESI, making it valuable for analyzing neutral lipids, steroids, and various pharmaceuticals [4] [3]. The APCI mechanism is depicted below.

APCI Ionization Process

Atmospheric Pressure Photoionization (APPI): An Emerging Technique

APPI is particularly useful for non-polar compounds that ionize poorly by both ESI and APCI, such as polyaromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) and certain lipids [1] [2]. Its mechanism shares the initial vaporization step with APCI but differs in the primary ionization energy source:

- Photoionization: A vacuum ultraviolet (VUV) lamp (e.g., krypton, 10.0 eV or xenon, 8.4 eV) replaces the corona discharge needle. Photons from the lamp can directly ionize analyte molecules (M) if the photon energy exceeds the analyte's ionization energy (IE), producing radical cations M⁺• [2].

- Dopant-Assisted Ionization: For analytes with a higher IE than the photon energy, a dopant (e.g., toluene, acetone) is added. The dopant is ionized first and then transfers a charge to the analyte molecule through proton or electron transfer reactions [2].

Performance Comparison and Factors Affecting Ionization Efficiency

The choice between ESI and APCI is not trivial and has a profound impact on the success of an LC-MS analysis. Performance is governed by a complex interplay of analyte properties, mobile phase composition, and instrument parameters.

Analytical Performance in Applied Studies

Direct comparisons in real-world applications highlight the complementary nature of ESI and APCI. The following tables summarize key findings from targeted analyses in food safety and metabolomics.

Table 1: Comparison of ESI and APCI for Pesticide Analysis in a Cabbage Matrix [4] [5]

| Performance Parameter | ESI Performance | APCI Performance | Context and Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Linear Range | 0.5 - 200 μg/kg | 0.5 - 200 μg/kg | Both techniques showed acceptable linearity for multi-residue analysis over this range. |

| Limit of Quantification (LOQ) | 0.5 - 1.0 μg/kg | 1.0 - 2.0 μg/kg | ESI demonstrated superior sensitivity (lower LOQs) for most of the 22 pesticides studied. |

| Matrix Effect | Less intense | More intense | APCI suffered from greater matrix-induced signal suppression or enhancement, complicating quantification. |

| Overall Efficiency | Greater | Good | For this multi-residue analysis, ESI was determined to be the more efficient ionization source. |

Table 2: Comparison of ESI and APCI in Metabolomics Analysis of Grape Berry Extracts [6]

| Performance Parameter | ESI Performance | APCI Performance | Context and Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ionization Preference | Moderately polar metabolites (flavanols, flavones, anthocyanins) | Strongly polar metabolites (sugars, organic acids) & weakly polar metabolites | The techniques are not merely complementary but have distinct optimal application spaces. |

| Typical Ions Generated | More adduct ions [M+Na]⁺, [M+K]⁺ | More fragment ions | ESI data may require careful adduct deconvolution, while APCI can provide more structural fragments. |

| Limit of Detection (LOD) | Lower for sucrose, tartaric acid | Higher for sucrose, tartaric acid | Contradicts the general rule that APCI is better for sugars, highlighting the need for empirical testing. |

| Linear Range | Narrower | Wider | APCI offered a wider dynamic range for the compounds studied. |

| Matrix Effects | Greater | Lesser | ESI was more susceptible to matrix effects in this complex plant extract. |

Key Factors Influencing Ionization Efficiency

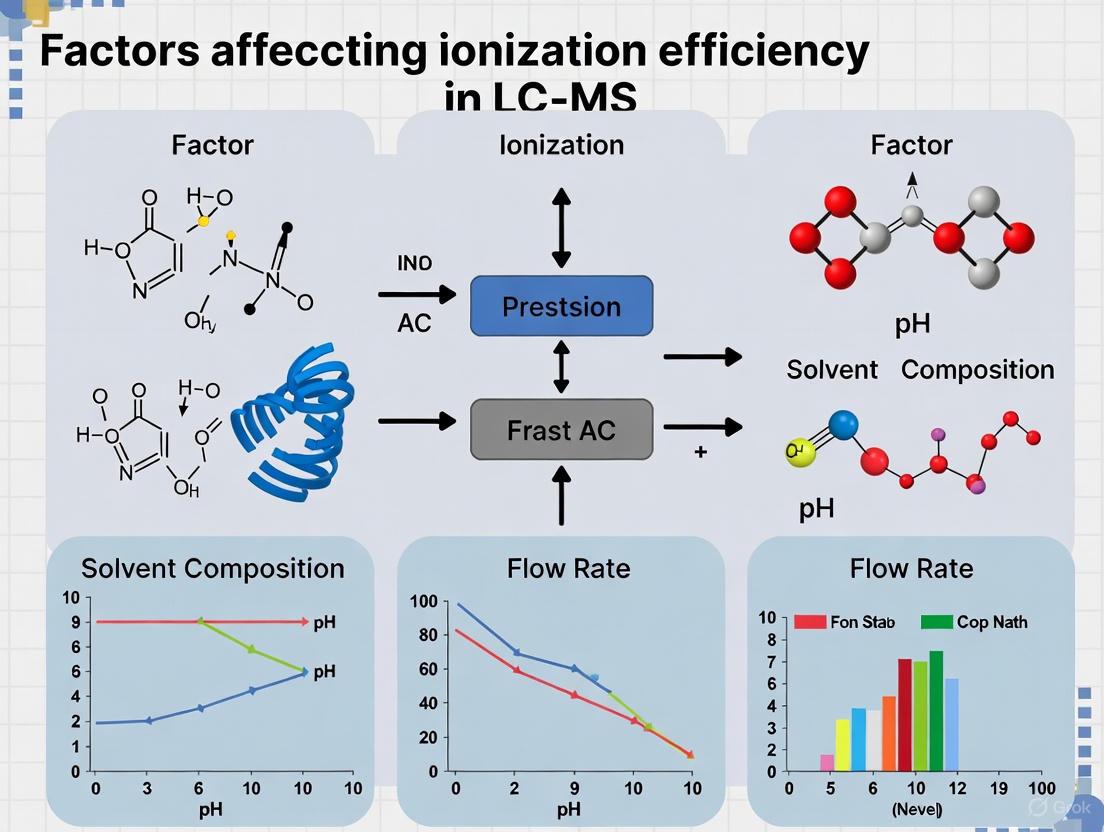

The following diagram synthesizes the critical factors that researchers must control and optimize to maximize ionization efficiency in LC-MS.

Factors Affecting Ionization Efficiency

Experimental Protocols and Method Development

A systematic approach for evaluating ionization source performance in non-targeted metabolomics involves a minimal, resource-efficient pilot experiment [7].

1. Objective: To compare the sensitivity and selectivity of two LC-HRMS instrumental setups (e.g., a standard ESI source vs. an alternative high-temperature ESI source) for profiling a complex biological sample.

2. Sample Preparation:

- Prepare a dilution series of a representative pooled biological sample (e.g., urine, plasma extract, or tissue homogenate). An eight-point, sequential one-in-four dilution series is effective, ranging from the neat sample to a 1:16,384 dilution [7].

- This series accounts for the large dynamic range of metabolites and avoids signal saturation when comparing sources with different inherent sensitivities.

3. Instrumental Analysis:

- Analyze the entire dilution series for each instrumental setup (REF and ALT) using identical LC conditions. It is advisable to test multiple chromatographic methods (e.g., Reversed-Phase and HILIC) to ensure robustness [7].

- LC Conditions (Example):

- Column: C18 (for RPC) or amide (for HILIC), 2.0 mm internal diameter to optimize ESI flow rates.

- Flow Rate: 0.2 - 0.4 mL/min.

- Mobile Phase: Appropriate gradients for RPC (Water/Acetonitrile with 0.1% Formic Acid) and HILIC (Acetonitrile/Water with Ammonium Acetate or Formate).

- MS Conditions:

- Mass Analyzer: High-resolution mass spectrometer (e.g., Q-TOF, Orbitrap).

- Scan Mode: Full-scan MS in both positive and negative ionization modes.

- Source Parameters: Optimize and fix parameters for each source (capillary voltage, vaporizer temperature, gas flows) according to manufacturer guidelines.

4. Data Processing and Statistical Evaluation:

- Process raw data using non-targeted software (e.g., XCMS, Progenesis QI) for feature detection, alignment, and integration. A "feature" is defined by a unique (m/z) and retention time pair [7].

- Feature-based Evaluation:

- Assemble all feature intensities into a data matrix.

- Calculate "robust" fold-changes for features across all dilution levels to compare the overall sensitivity (REF vs. ALT). A large proportion of features (e.g., 76-83%) with higher intensity in one setup indicates a clear sensitivity advantage [7].

- Analyze the subset of features unique to each setup to assess selectivity differences.

- Chemical Interpretation:

- Perform compound identification on a subset of significant features using accurate mass, MS/MS libraries, and standard matching.

- Classify compounds by chemical class (e.g., sugars, lipids, amino acids) to determine if performance differences are structure-dependent.

5. Validation with Targeted Analysis (Optional but Recommended):

- Validate conclusions by analyzing a large panel of authenticated metabolite standards (e.g., 300+ compounds) under the same conditions.

- Compare LODs, LOQs, and linear dynamic ranges for a direct, quantitative performance assessment [7].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents and materials essential for developing and optimizing LC-MS methods with ESI and APCI.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for LC-MS Ionization

| Reagent / Material | Function / Purpose | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| HPLC-Grade Solvents (Water, Methanol, Acetonitrile) | Mobile phase constituents; must be high-purity to minimize chemical noise and contamination. | Low UV cutoff, low residue after evaporation, and minimal ion-pairing agent content are critical. |

| Volatile Buffers & Additives (Formic Acid, Acetic Acid, Ammonium Formate, Ammonium Acetate) | Adjust mobile phase pH to promote analyte protonation/deprotonation. Facilitate ion formation in ESI. | Typical concentrations are 0.05% - 0.1% for acids and 2-10 mM for ammonium salts. Avoid non-volatile buffers (e.g., phosphate). |

| Mass Spectrometry Calibration Solution | Accurate mass calibration of the mass spectrometer before analysis. | Commercially available solutions (e.g., Pierce LTQ Velos ESI Positive Ion Calibration Solution) containing a mixture of compounds across a broad (m/z) range. |

| Chemical Standard Mixtures | Method development, optimization, and quantitative calibration. | Used to test ionization efficiency, chromatographic separation, and determine LOD/LOQ for target analytes. |

| QuEChERS Extraction Kits | Sample preparation for complex matrices (e.g., food, biological tissues). | A standardized "Quick, Easy, Cheap, Effective, Rugged, Safe" method for multi-residue analysis, often used prior to LC-ESI/APCI-MS/MS [4]. |

| Dopants (Toluene, Acetone) | Enhance ionization efficiency in APPI. | The dopant has a lower ionization energy (IE) than the mobile phase solvents and is ionized by the VUV lamp, subsequently ionizing the analyte [2]. |

Emerging Trends and Future Directions

The field of LC-MS ionization continues to evolve, driven by demands for higher sensitivity, robustness, and broader chemical comprehensiveness.

- Source Integration and High-Throughput: The development of fast-switching dual ionization sources that can operate in both ESI and APCI modes, either simultaneously or in rapid alternation, is a significant advancement. This allows a single instrument to cover a wider chemical space without manual source swapping, thereby increasing laboratory throughput and efficiency [8].

- Advanced Source Design: New ion source geometries and technologies are being introduced to improve ionization efficiency and reduce matrix effects. Examples include sources with redesigned gas sheaths and higher operating temperatures (e.g., "IonBooster" interfaces), which have shown promise in increasing sensitivity for a range of compound classes in metabolomics [7].

- Standardization and Data Science: As metabolomics and non-targeted analysis move into regulatory and clinical settings, there is a growing emphasis on method harmonization. Research is focusing on using non-targeted pilot experiments and machine learning to predict ionization efficiency, aiming to replace costly and time-consuming targeted evaluation procedures with more efficient, data-driven approaches [7] [9].

- Broadening Application Space: APCI is being re-evaluated and recognized as an essential tool for analyzing challenging low molecular weight, thermally labile, and low-polarity synthetic molecules that are problematic for both EI and ESI, thus expanding the accessible chemical space for routine analysis [10].

The ionization of an analyte is the critical first step in Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS) that determines the success of the entire analysis. Ionization efficiency directly influences the sensitivity, reproducibility, and overall capability of an LC-MS method. This guide details the core physicochemical properties—pKa, polarity, surface activity, and molecular structure—that govern ionization efficiency, providing a foundational framework for a broader thesis on factors affecting LC-MS performance. Understanding these properties enables researchers to predict analyte behavior, optimize methods systematically, and troubleshoot analytical challenges in drug development and other research applications. The principles discussed herein are particularly vital for the analysis of pharmaceutical compounds, a majority of which contain ionizable groups [11].

Core Properties and Their Impact on Ionization

pKa and Ionization State

The acid dissociation constant (pKa) is arguably the most significant property controlling ionization in LC-MS. It defines the pH at which a molecule exists in a dynamic equilibrium, with 50% of its population in an ionized state and 50% in a neutral state [11] [12]. The relationship between pH, pKa, and the degree of ionization for monoprotic acids and bases is quantitatively described by the Henderson-Hasselbalch equation [13].

For acids: pH = pKa + log([A⁻]/[HA]) For bases: pH = pKa + log([B]/[BH⁺])

At a pH equal to the analyte's pKa, the mixture of ionized and neutral species can lead to broad or tailing peaks in chromatography and inconsistent ionization in the mass spectrometer [11] [12]. To ensure stable and efficient ionization, the mobile phase pH should be adjusted to at least two units away from the analyte's pKa. This ensures the compound is predominantly (>99%) in a single, predictable ionization state [11]. It is crucial to remember that pKa is not a true constant but depends on temperature, ionic strength, and the solvent composition [13].

Table 1: pKa-Driven HPLC Method Development Strategy

| Analyte Type | Target Mobile Phase pH | Rationale | Impact on Ionization |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acidic | 2 units below pKa | Suppresses dissociation, maintains neutral form | Promotes protonation in positive mode; reduces ion suppression |

| Basic | 2 units above pKa | Suppresses protonation, maintains neutral form | Promotes deprotonation in negative mode; reduces ion suppression |

| At pKa | pH = pKa | 50% ionized, 50% unionized | Unstable ionization leads to poor peak shape and variable signal [12] |

Polarity and Lipophilicity

Polarity, often quantified by the octanol-water partition coefficient (log P), measures the relative affinity of a molecule for polar versus non-polar environments. In LC-MS, polarity is a double-edged sword. Highly polar compounds are readily soluble in the aqueous mobile phase but may not adsorb effectively to the charged droplet surface during electrospray ionization (ESI), leading to poor efficiency. Conversely, very non-polar (lipophilic) compounds, while easily concentrating at the droplet surface, often have low solubility in the LC mobile phase, risking precipitation and adsorption [14].

The optimal balance is a molecule with moderate lipophilicity. Such analytes can effectively partition to the droplet surface in ESI while remaining in solution throughout the chromatographic process. Lipophilicity is a critical parameter for all ADMET (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity) properties of a drug, influencing not just ionization but also permeability and metabolic stability [14].

Surface Activity

Surface activity refers to an analyte's ability to preferentially concentrate at the interface between the liquid droplet and the gas phase in ESI. This property is governed by the compound's amphiphilic nature, meaning it possesses both polar and non-polar regions. Surface-active analytes (e.g., phospholipids, surfactants) will accumulate at the droplet surface, thereby gaining preferential access to the charge and leading to enhanced ionization efficiency. This phenomenon can cause significant ion suppression for less surface-active co-eluting compounds, as the surface-active agents effectively "compete" for the available charge and space on the limited droplet surface [15]. This is a primary component of the matrix effect in bioanalysis, where endogenous compounds from the sample matrix suppress or enhance the ionization of the target analyte [15].

Molecular Structure and Intrinsic Properties

The fundamental molecular structure of an analyte dictates its intrinsic potential for ionization.

- Ionizable Groups: The presence and type of functional groups (e.g., carboxylic acids, amines, phosphates) determine how readily a molecule can gain or lose a proton. Molecules with multiple ionizable centers can present complex ionization profiles [11].

- Gas-Phase Basicity/ Acidity: This is the thermodynamic propensity of an ionized molecule to retain its charge in the gas phase after the solvent has evaporated. A higher gas-phase basicity (for positive ions) or lower gas-phase acidity (for negative ions) leads to more stable ions and a stronger signal.

- Molecular Size and Lability: Large, labile molecules (e.g., proteins, peptides) can be gently ionized by ESI to produce a spectrum of multiply-charged ions [M+nH]ⁿ⁺, which allows the mass analysis of high-molecular-weight species on instruments with limited m/z range [16].

Table 2: Summary of Analyte Properties and Their Influence on Ionization

| Property | Mechanism of Influence | Primary Ionization Impact | Preferred ESI Mode |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low pKa (Acidic) | Proton donation in solution | Forms stable [M-H]⁻ ions | Negative Mode |

| High pKa (Basic) | Proton acceptance in solution | Forms stable [M+H]⁺ ions | Positive Mode |

| High Polarity | High aqueous solubility, poor surface activity | Low ionization efficiency; may require derivatization | Depends on ionizable group |

| High Surface Activity | Preferential concentration at droplet surface | High ionization efficiency; causes ion suppression | Depends on ionizable group |

| Multiple Ionizable Groups | Can accept/donate multiple protons | Can form multiply-charged ions [M+nH]ⁿ⁺ [16] | Positive or Negative Mode |

Experimental Protocols for Investigation

Protocol for Determining pKa and Its Ionization Impact

Objective: To determine the pKa of an analyte and experimentally observe its effect on LC-MS response. Background: The pKa of a compound can be determined by measuring a spectroscopic or chromatographic property as a function of pH. The resulting sigmoidal curve will have an inflection point at the pKa [13].

Materials:

- Test analyte at a known concentration.

- A series of buffered mobile phases covering a pH range from at least 3 units below to 3 units above the predicted pKa.

- LC-MS system with a UV detector and mass spectrometer.

Method:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare identical solutions of the test analyte in each of the buffered mobile phases.

- LC-MS Analysis: Inject each sample onto the LC-MS system. Use an isocratic or shallow gradient method to minimize retention time shifts.

- Data Collection: For each injection, record:

- The UV peak area.

- The MS extracted ion chromatogram (XIC) peak area.

- The analyte's retention time (k).

- Data Analysis:

- Plot the UV response, MS response, and retention time against the mobile phase pH.

- Fit a sigmoidal curve to the data. The pH at the inflection point of the retention time plot corresponds to the pKa.

- Identify the pH regions where the MS signal is maximized and most stable.

Protocol for Assessing Matrix Effect and Surface Activity

Objective: To quantify ion suppression/enhancement caused by matrix components and infer surface activity. Background: This protocol, based on the methods of Matuszewski et al., uses pre- and post-extraction spiking to differentiate between recovery losses and true ionization effects [15].

Materials:

- Blank biological matrix (e.g., plasma, urine) from at least 6 different lots [15].

- Neat solvent (mobile phase).

- Stock solutions of the analyte and internal standard (IS).

Method:

- Sample Set Preparation: Prepare three sets of samples for each matrix lot and at two concentration levels [15]:

- Set 1 (Neat Solution): Spike analyte and IS into neat solvent. This represents the 100% reference signal (A).

- Set 2 (Post-extraction Spiked): Spike analyte and IS into extracted blank matrix. This measures the matrix effect (ME); the signal is designated (B).

- Set 3 (Pre-extraction Spiked): Spike analyte into the blank matrix before extraction, then add IS after extraction. This measures the process efficiency (PE); the signal is designated (C).

- LC-MS/MS Analysis: Analyze all samples using the validated MRM method.

- Calculations:

- Matrix Effect (ME): ME% = (B / A) × 100. An ME < 100% indicates ion suppression; >100% indicates enhancement.

- Process Efficiency (PE): PE% = (C / A) × 100.

- Recovery (RE): RE% = (C / B) × 100. This isolates the extraction efficiency from the ionization effect.

- Interpretation: A low ME% with a high RE% indicates strong ion suppression, often caused by co-eluting, highly surface-active matrix components outcompeting the analyte for charge.

Ionization Pathways and Experimental Workflows

The following diagram illustrates the logical decision process for optimizing ionization based on analyte properties, leading to the appropriate experimental workflow for assessment.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful LC-MS analysis, particularly when investigating ionization properties, requires careful selection of reagents and materials. The following toolkit outlines essential items and their functions.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions and Materials for Ionization Studies

| Item | Function / Purpose | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Buffers (e.g., Ammonium Formate/Acetate) | Controls pH of the mobile phase to manipulate analyte ionization state [11]. | Must be volatile to prevent clogging the MS interface and contaminating the ion source. |

| LC-MS Grade Solvents (Water, MeCN, MeOH) | Serves as the mobile phase for chromatographic separation and ionization matrix. | High purity minimizes background noise and prevents instrument contamination. |

| pKa Standards | Used for calibration and verification of predictive models or experimental determinations. | A set of compounds with known, well-defined pKa values across a broad pH range. |

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Internal Standards | Accounts for variability in sample preparation and ionization efficiency, correcting for matrix effects [15]. | Ideally, the IS is an isotopolog of the analyte and added at the earliest possible step. |

| Blank Matrix Lots (≥6) | Essential for experimental assessment of matrix effects and ion suppression [15]. | Sourced from multiple donors to account for biological variability. |

| Syringe Pumps | Provides precise, pulseless flow for direct infusion studies or for delivering calibration solutions [17]. | Crucial for fundamental ionization studies and instrument calibration. |

In Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS), successful analysis depends not only on effective chromatographic separation but also on efficient ionization of analytes for detection. The mobile phase composition is the critical bridge between these two processes, directly influencing the ionization efficiency in the electrospray ionization (ESI) source, which is the most commonly applied interface for LC-MS [18]. The chemical environment created by volatile buffers, specific pH levels, and organic modifiers either enhances or suppresses the signal of target analytes, ultimately determining method sensitivity, limits of detection, and quantification reliability [19]. This technical guide examines the fundamental relationships between mobile phase constituents and ESI response, providing evidence-based strategies for optimizing LC-MS methods within the broader context of ionization efficiency research.

Core Principles of Mobile Phase Effects on Ionization

The Electrospray Ionization Mechanism and Liquid-Phase Interactions

Electrospray ionization involves the formation of charged droplets from the LC eluent, followed by solvent evaporation and repeated droplet fissions until gas-phase ions are released [19]. The chemical composition of the mobile phase critically impacts the desorption efficiency of analytes from charged droplets into the gas phase [20]. Key properties influenced by the mobile phase include:

- Solution conductivity affecting Taylor cone stability

- Surface tension influencing initial droplet size

- Solvent evaporation rate controlling droplet shrinkage and fission events

- Gas-phase proton affinity governing final ion formation

Ionization efficiency varies significantly with the mobile phase environment, with response factors for chemicals spanning 4-6 orders of magnitude across different conditions [21]. This dramatic variation underscores the importance of systematic mobile phase optimization.

Volatile Buffers: MS-Compatibility and Ionization Mechanisms

Volatile buffers are essential for LC-MS because they produce minimal residue in the ion source, preventing contamination and signal suppression. Non-volatile buffers (e.g., phosphates) form crystalline deposits that degrade MS performance and necessitate frequent source cleaning [22].

Table 1: Common Volatile Buffers in LC-MS and Their Properties

| Buffer System | Useful pH Range | Molecular Weight | Volatility | Compatibility Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ammonium Formate | 2.8-4.8 / 8.2-10.2 | 63.06 | High | Excellent for positive and negative mode |

| Ammonium Acetate | 3.8-5.8 / 8.2-10.2 | 77.08 | High | Most versatile; wide application range |

| Formic Acid | 3.3-4.3 | 46.03 | High | Excellent for positive ion mode |

| Acetic Acid | 4.3-5.3 | 60.05 | High | Weaker acidity than formic acid |

| Ammonium Bicarbonate | 5.9-6.9 / 8.8-9.8 | 79.06 | Moderate | Suitable for higher pH applications |

The chemical structure of buffer ions affects their ion-pairing potential and gas-phase proton transfer efficiency. For instance, alkylamines with higher Henry's Law Constant values (e.g., hexylamine, piperidine) can reduce charge state distribution of oligonucleotides by forming complexes that dissociate in the gas phase, while those with low values facilitate earlier ion emission [20].

Quantitative Optimization Strategies

Systematic Evaluation of Buffer Composition

A comprehensive study evaluating 240 FDA-approved drugs identified clear response patterns based on mobile phase composition [18]. The research employed standardized chromatographic conditions with a C18 reversed-phase column (ACQUITY UPLC BEH C18, 1.7µm, 2.1 × 100 mm) and electrospray ionization mass spectrometry.

Table 2: Optimal Mobile Phase Systems for Maximizing ESI Response [18]

| Organic Modifier | Buffer Additive | Relative Response | Applicable Compound Classes | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Methanol | Formic Acid | High | Largest number of compounds (including most drugs) | Best overall response for diverse analytes |

| Methanol | Ammonium Acetate | High | Broad applicability | Excellent for both positive and negative mode |

| Isopropanol | Formic Acid | Good | Selective compound classes | Good alternative to methanol systems |

| Isopropanol | Ammonium Acetate | Good | Selective compound classes | Complementary selectivity |

| Acetonitrile | Formic Acid | Moderate | Specific applications | Sharp peaks for certain separations |

| Acetonitrile | Acetic Acid | Moderate | Acid-stable compounds | Weaker ionization suppression |

The findings demonstrated that formic acid and ammonium acetate in methanol-based systems provided the best overall response for the largest number of compounds [18]. This combination offers optimal compatibility with ESI processes while maintaining effective separation for most small molecules.

pH Optimization and Charge State Control

Mobile phase pH significantly influences analyte ionization in solution prior to ESI, particularly for compounds with acidic or basic functional groups. The pH affects the degree of protonation for basic compounds in positive mode and deprotonation for acidic compounds in negative mode [18] [21].

For basic analytes, a pH 2-3 units below the pKa ensures >99% protonation, maximizing [M+H]+ signal. Conversely, for acidic compounds, a pH 2-3 units above the pKa promotes deprotonation, enhancing [M-H]- signal. When analyzing complex mixtures with diverse functional groups, pH selection represents a compromise that must be experimentally determined.

Organic Modifier Selection and Mechanisms

The organic modifier (typically acetonitrile, methanol, or isopropanol) affects multiple aspects of the LC-MS process:

- Solvation strength in reversed-phase chromatography

- Solution viscosity influencing droplet size in ESI

- Surface tension affecting Taylor cone formation

- Evaporation rate controlling desolvation efficiency

Methanol generally provides superior ionization efficiency compared to acetonitrile for most compounds, attributed to its protic nature which facilitates proton transfer reactions [18]. Isopropanol, while providing alternative selectivity, increases viscosity leading to broader peaks but can enhance response for certain hydrophobic compounds.

The modifier's impact extends to specialized applications; for oligonucleotide analysis, modifiers with specific Henry's Law Constants (e.g., hexafluoroisopropanol) significantly alter charge-state distribution and desorption efficiency [20].

Experimental Protocols for Method Development

Standardized Method Comparison Protocol

Objective: Systematically identify optimal mobile phase composition for maximum ESI response of target analytes.

Materials and Equipment:

- LC-MS system with ESI source and binary pump

- C18 reversed-phase column (e.g., 100 × 2.1 mm, 1.7-2.7 µm particle size)

- Volatile buffers: formic acid, acetic acid, ammonium acetate, ammonium formate (MS-grade)

- Organic modifiers: methanol, acetonitrile, isopropanol (MS-grade)

- Analytic standards prepared in compatible solvents

Procedure:

- Prepare mobile phase A: water with 0.1% buffer additive

- Prepare mobile phase B: organic modifier with 0.1% buffer additive

- Test buffer systems: formic acid (0.1%), acetic acid (0.1%), ammonium acetate (2-10 mM), ammonium formate (2-10 mM)

- For each buffer, test with different organic modifiers (methanol, acetonitrile)

- Employ a standardized gradient: 5-95% B over 10 minutes, hold 2 minutes

- Maintain constant flow rate (0.3-0.5 mL/min for 2.1 mm ID columns)

- Inject identical concentrations of analytes across all conditions

- Monitor peak areas, signal-to-noise ratios, and peak shapes

Data Analysis:

- Normalize responses to the highest signal for each analyte

- Identify compositions providing >80% of maximum response

- Evaluate peak symmetry and resolution

- Select conditions offering best compromise for multi-analyte methods

This systematic approach mirrors methodology successfully applied in pharmaceutical compound screening [18].

Ion Source Parameter Optimization Protocol

Objective: Fine-tune ESI source parameters for specific mobile phase composition.

Background: Optimal source conditions are dependent on mobile phase composition and flow rate [19].

Diagram: ESI Source Optimization Workflow. S/N = Signal-to-Noise ratio.

Procedure:

- Begin with manufacturer-recommended settings for your flow rate

- Inject a standard solution while varying capillary voltage (typically 2-4 kV in steps of 0.2 kV)

- Monitor total ion current stability and signal intensity

- Optimize nebulizer gas pressure (20-60 psi) to achieve stable spray

- Adjust desolvation temperature (200-500°C) for maximum signal without degrading thermally labile compounds

- Fine-tune source positions for optimal ion transmission

- Iterate process for critical analytes

Documented optimizations demonstrate 2-3 fold sensitivity improvements through systematic source parameter adjustment [19].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Materials for LC-MS Mobile Phase Optimization

| Category | Specific Reagents | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Volatile Acids | Formic Acid (0.05-0.1%)Acetic Acid (0.05-0.1%) | Protonate basic analytesProvide low pH environment | Formic acid: stronger acidityAcetic acid: alternative selectivity |

| Volatile Salts | Ammonium Acetate (2-20 mM)Ammonium Formate (2-20 mM) | pH ControlBuffer capacity | Ammonium formate: more volatileAmmonium acetate: wider application |

| Organic Modifiers | MethanolAcetonitrileIsopropanol | Solvation strengthImpact ESI efficiency | Methanol: best overall responseAcetonitrile: different selectivity |

| Specialty Additives | HexafluoroisopropanolAlkylamines (e.g., imidazole) | Modify charge stateEnhance desorption | Oligonucleotide analysisChallenging ionizations |

| Column Chemistry | C18 (standard)Phenyl-HexylHILICBiphenyl | Stationary phase selectivityAlternative interactions | Complementary selectivityChallenging separations [23] |

Advanced Applications and Emerging Trends

Machine Learning Approaches for Ionization Efficiency Prediction

Emerging approaches utilize machine learning models to predict ionization efficiency based on molecular descriptors and mobile phase composition [21]. Random forest regression models trained on PaDEL descriptors can predict response factors with median errors of 2.20× for SFC/ESI/HRMS and 5.11× when transferring models between techniques [21]. These quantitative structure-retention relationship (QSRR) models incorporate descriptors for:

- Molecular lipophilicity (log P)

- Polar surface area

- Hydrogen bonding capacity

- Aromaticity indices

- Charge distribution parameters

The most significant molecular descriptors show remarkable consistency across different chromatographic techniques, enabling cross-platform prediction models that accelerate method development [18] [21].

Inert Hardware for Challenging Analyses

Recent column technology innovations focus on inert hardware to minimize metal-analyte interactions that compromise recovery for metal-sensitive compounds [23]. These include:

- Metal-free fluid paths for phosphorylated compounds

- Passivated stainless steel for chelating analytes

- PEEK-lined systems for bioinert applications

Such technologies demonstrate enhanced peak shapes and improved analyte recovery for challenging molecules like phosphorylated drugs, chelating pesticides, and oligonucleotides [23].

Mobile phase composition serves as the critical link between chromatographic separation and mass spectrometric detection in LC-MS. Through strategic selection of volatile buffers, optimization of pH based on analyte physicochemical properties, and appropriate choice of organic modifiers, analysts can significantly enhance ionization efficiency and method sensitivity. The systematic experimental approaches outlined in this guide provide a framework for evidence-based method development, while emerging technologies in column hardware and predictive modeling offer new opportunities for optimization. As LC-MS applications continue to expand into increasingly complex analytical challenges, fundamental understanding of mobile phase effects on ionization processes remains essential for generating robust, sensitive, and reliable analytical methods.

Matrix effects represent a fundamental challenge in liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS), profoundly impacting the accuracy, reproducibility, and sensitivity of quantitative analyses across pharmaceutical, clinical, and environmental applications. These effects occur when components co-eluting with target analytes interfere with the ionization process in the mass spectrometer interface, leading to either suppression or enhancement of the analyte signal [24] [25]. Regardless of the sensitivity or selectivity of the mass analyzer used, matrix effects negatively affect critical analytical figures of merit including detection capability, precision, and accuracy [24]. The limited knowledge of the origin and mechanism of these effects makes them particularly difficult to solve in many cases, necessitating a comprehensive understanding of their causes, detection methods, and mitigation strategies [24].

The pervasive nature of matrix effects has been increasingly recognized since the early 1990s, when studies began reporting difficulties with reproducibility and accuracy when analyzing small quantities of analytes in complex samples such as biological fluids [24]. Kebarle and Tang originally described the matrix effect phenomenon as the result of co-eluted matrix components affecting the detection capability, precision, or accuracy for analytes of interest [24]. Ion suppression specifically refers to the manifestation of matrix effects associated with influencing the extent of analyte ionization, often observed as a loss in response [24]. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration's Guidance for Industry on Bioanalytical Method Validation clearly indicates the need for matrix effect assessment to ensure that precision, selectivity, and sensitivity will not be compromised, though specific assessment procedures are not prescribed [25].

Mechanisms and Origins of Ion Suppression and Enhancement

Fundamental Ionization Interference Processes

Matrix effects originate from competitive processes occurring during ionization where co-eluting compounds interfere with the efficient ionization of target analytes. In electrospray ionization (ESI), the most widely used LC-MS interface, ionization occurs through the formation of charged droplets that undergo desolvation and Coulombic fission until gas-phase ions are produced [24]. Matrix effects in ESI primarily arise from competition for charge and space on the surface of these droplets [24]. At high concentrations (>10⁻⁵ M), the approximate linearity of the ESI response is often lost due to either a limited amount of excess charge available on ESI droplets or saturation of the ESI droplets with analyte at their surfaces, thus inhibiting ejection of ions trapped inside the droplets [24].

The characteristics that determine whether a compound will out-compete others for the limited charge or space include its surface activity and basicity [24]. Biological matrices contain large amounts of endogenous compounds with potentially very high basicities and surface activities, causing the concentration limit of 10⁻⁵ M to be reached quickly, resulting in ion suppression [24]. Alternative theories propose that increased viscosity and surface tension of droplets from high concentrations of interfering compounds can reduce solvent evaporation and the ability of the analyte to reach the gas phase [24] [26]. Nonvolatile materials may also decrease droplet formation efficiency through coprecipitation of analyte or preventing droplets from reaching the critical radius required for gas phase ion emission [24].

Ionization Technique Dependencies

The mechanisms and severity of matrix effects differ significantly between ionization techniques. Atmospheric-pressure chemical ionization (APCI) frequently exhibits less ion suppression than ESI due to fundamental differences in their ionization mechanisms [24]. Unlike ESI, APCI does not involve competition between analytes to enter the gas phase, as neutral analytes are transferred into the gas phase by vaporizing the liquid in a heated gas stream [24]. Additionally, ion suppression in APCI is not directly related to charge saturation because the maximum number of ions formed by gas-phase ionization is much higher, with reagent ions being redundantly formed [24]. Nonetheless, APCI does experience ion suppression, which has been explained by considering the effect of sample composition on the efficiency of charge transfer from the corona discharge needle, or through solid formation either as pure analyte or as a solid coprecipitate with other nonvolatile sample components [24].

Emerging ionization techniques show promise for reducing matrix effects. Flexible microtube plasma (FμTP) ionization, a dielectric barrier discharge-based method, has demonstrated significantly reduced matrix effects compared to conventional ESI and APCI [27]. In comparative studies, between 76% and 86% of pesticides showed negligible matrix effects for FμTP, compared to 35–67% for ESI and 55–75% for APCI across different matrices [27]. This improvement is attributed to differences in ionization mechanisms, with plasma-based techniques potentially offering more robust performance in complex matrices.

The sources of ion suppression include both endogenous compounds originating from the sample matrices and exogenous substances introduced during sample preparation [24] [25]. Compounds with high concentration, mass, and basicity that elute in the same retention window as the analyte of interest are prime candidates for inducing ion suppression [24]. Phospholipids in plasma represent one of the most significant sources of matrix effects in bioanalysis [28]. Other common sources include salts, metabolites, dosing vehicle components, and polymers extracted from plastic tubes during sample preparation [24] [25]. Column bleed from chromatographic stationary phases can also contribute to matrix effects, with hydrolysis products from conventional silica-based mixed-mode columns causing significant ion suppression or enhancement, while hybrid particle-based columns demonstrate markedly lower effects [29].

Table 1: Common Sources of Matrix Effects in LC-MS Analysis

| Source Type | Specific Examples | Impact on Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Endogenous | Phospholipids, bile acids, lipids, proteins, metabolites | High concentration in biological matrices; co-elution with analytes causes competitive ionization [30] [28] |

| Exogenous | Polymers from plasticware, dosing vehicle components, SPE cartridge leachates | Introduced during sample preparation; varies between batches and suppliers [24] [25] |

| Chromatographic | Stationary phase bleed, ion-pairing reagents, mobile phase additives | High background signal; interference with analyte ionization [29] [25] |

| Sample-Derived | High lipid content, salts, residual precipitating agents | Increases viscosity and surface tension; affects droplet formation and evaporation [24] [26] |

Detecting and Evaluating Matrix Effects

Established Experimental Protocols

Several experimental approaches have been developed to detect and evaluate matrix effects during method development and validation. The post-extraction spike method involves comparing the MRM response (peak areas or heights) of an analyte in a blank sample spiked post-extraction to that of the analyte injected directly into neat mobile phase [24] [26]. If the analyte signal in the matrix is significantly lower than in pure solvent, this indicates ion suppression from interfering agents [24]. While this approach quantitatively measures the extent of suppression, it does not provide information about the chromatographic location of the interference [24].

The post-column infusion method qualitatively identifies regions in the chromatogram affected by matrix effects [24] [26]. This technique involves continuous introduction of a standard solution containing the analytes of interest via a syringe pump connected to the column effluent [24]. After injecting a blank sample extract, a drop in the constant baseline indicates ionization suppression due to eluting interfering materials [24]. This method effectively maps suppression regions throughout the chromatogram, enabling method development to shift analyte retention away from problematic regions [24]. However, the process is time-consuming, requires additional hardware, and presents challenges for multianalyte methods [26].

Diagram 1: Post-Column Infusion Experiment Setup. This qualitative method identifies chromatographic regions affected by matrix effects by monitoring signal decreases during blank matrix injection.

Advanced Quantitative Assessment Methods

Recent advances in matrix effect assessment include more comprehensive quantitative approaches. The IROA TruQuant Workflow represents a significant innovation for non-targeted metabolomics, using a stable isotope-labeled internal standard (IROA-IS) library and companion algorithms to measure and correct for ion suppression [31]. This approach leverages a unique, formula-specific isotopolog ladder created by low ¹³C (natural abundance) signals and high ¹³C (95%) signals to distinguish real metabolites from artifacts and quantify suppression levels [31]. The method has demonstrated effectiveness across ion chromatography (IC), hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography (HILIC), and reversed-phase liquid chromatography (RPLC)-MS systems in both positive and negative ionization modes, with detected metabolites exhibiting ion suppression ranging from 1% to >90% [31].

Another innovative approach involves calculating a matrix factor derived from the ratio of analyte signal response with and without matrix presence [29]. This method has been applied to evaluate column bleed from different stationary phases, demonstrating that silica-based mixed-mode columns produce matrix factors ranging from 0.04 to 1.86 (indicating severe suppression to significant enhancement), while hybrid particle-based columns yield matrix factors closest to 1 (0.74–1.16), showing minimal ion suppression or enhancement [29].

Consequences and Impact on Analytical Data Quality

Effects on Quantitative Analytical Figures of Merit

Matrix effects negatively impact multiple analytical performance characteristics essential for reliable quantitative analysis. The detection capability is reduced due to decreased analyte signal, leading to higher limits of detection (LOD), lower signal-to-noise (S/N) ratios, and a smaller dynamic range [25]. Precision is compromised as the degree of suppression may vary between samples due to natural biological variation in matrix composition [24] [25]. This variation can introduce both systematic and random errors in signal response, affecting ion intensity ratios and linearities [24]. In severe cases, ion suppression can lead to false negatives for existing analytes or false positives in applications where maximum residue limits are monitored, particularly if the internal standard experiences different suppression than the analyte [24].

The consequences extend beyond simple signal reduction. Matrix effects can significantly alter chromatographic behavior, with studies demonstrating that matrix components can change the retention time (Rt) and shape of LC peaks [30]. In extreme cases, matrix effects have been shown to cause a single compound to yield two LC peaks, fundamentally challenging the established rule that one chemical compound yields one LC-peak with reliable retention time [30]. This phenomenon was observed for bile acid standards including chenodeoxycholic acid, deoxycholic acid, and glycocholic acid when analyzed in urine samples from animals fed different diets [30]. The proposed mechanism suggests that some matrix components may loosely bond to analytes, changing their retention characteristics and interfering with ionization [30].

Table 2: Impact of Matrix Effects on Analytical Performance Parameters

| Analytical Parameter | Effect of Ion Suppression | Consequence for Data Quality |

|---|---|---|

| Detection Capability | Decreased analyte signal intensity | Higher LOD/LOQ; reduced sensitivity for trace analysis [25] |

| Precision | Variable suppression between samples | Poor reproducibility and method robustness [24] [25] |

| Accuracy | Altered analyte response factor | Inaccurate quantification; potential for false positives/negatives [24] |

| Linearity | Non-proportional response with concentration | Reduced dynamic range; compromised calibration reliability [25] |

| Retention Time | Altered interaction with stationary phase | Erroneous peak identification; integration errors [30] |

Strategies for Overcoming Matrix Effects

Sample Preparation and Chromatographic Solutions

Effective sample preparation represents the first line of defense against matrix effects. Selective extraction techniques, including liquid-liquid extraction (LLE) and solid-phase extraction (SPE), can remove interfering compounds before analysis [25]. The use of enhanced matrix removal-lipid (EMR) sorbents specifically targets phospholipids, a major source of matrix effects in biological samples [27]. Cleaner sample preparation approaches significantly reduce matrix component concentrations, though they may not eliminate compounds chemically similar to the analyte that are likely to co-elute [26].

Chromatographic optimization provides another crucial strategy for mitigating matrix effects. Improving separation to prevent co-elution of analytes and interfering compounds can significantly reduce ionization interference [26]. This includes adjusting stationary phase chemistry, mobile phase composition, and gradient profiles to shift analyte retention away from suppression regions identified by post-column infusion [24] [26]. However, modifying chromatographic conditions can be time-consuming, and some mobile phase additives may themselves suppress electrospray signals [26]. Alternative chromatographic approaches such as using longer columns, slower gradients, or multidimensional separation can improve resolution but at the cost of increased analysis time [25].

Internal Standardization and Calibration Techniques

Internal standardization represents the most effective approach for compensating for matrix effects rather than eliminating them. Stable isotope-labeled internal standards (SIL-IS) are considered the gold standard for quantitative compensation because they possess nearly identical chemical properties to the analytes, including retention time and ionization characteristics, and thus experience virtually the same matrix effects [26] [31]. The IROA TruQuant Workflow exemplifies an advanced implementation of this principle, using a comprehensive stable isotope-labeled internal standard library to correct for ion suppression across all detected metabolites in non-targeted studies [31].

When stable isotope-labeled standards are unavailable or prohibitively expensive, alternative calibration approaches may be employed. The standard addition method, widely used in spectroscopic techniques, shows promise for compensating matrix effects in LC-MS, particularly for endogenous analytes where blank matrix is unavailable [26]. This method involves spiking samples with increasing known concentrations of analyte and extrapolating to determine the original concentration [26]. Structural analogues that co-elute with the target analyte can also serve as internal standards, though with potentially lower compensation accuracy compared to SIL-IS [26].

Diagram 2: Comprehensive Matrix Effect Mitigation Workflow. Effective management requires multiple complementary approaches from sample preparation through data analysis.

Instrumental and Ionization Source Considerations

Instrumental modifications and alternative ionization techniques offer additional avenues for reducing matrix effects. Diluting samples before injection can minimize matrix component concentrations, though this approach is only feasible when assay sensitivity is sufficiently high [26]. Switching ionization modes (e.g., from positive to negative ionization) may reduce matrix effects since fewer compounds typically respond in negative mode [24]. Alternative ionization sources such as APCI often exhibit less severe matrix effects compared to ESI due to their different ionization mechanisms occurring primarily in the gas phase rather than in solution [24].

Emerging ionization technologies show particular promise for mitigating matrix effects. Flexible microtube plasma (FμTP) ionization, a dielectric barrier discharge-based technique, has demonstrated significantly reduced matrix effects compared to both ESI and APCI [27]. This source expands the chemical space coverage while providing more robust performance in complex matrices, making it valuable for both target and non-target screening applications [27]. The ionization mechanism in FμTP differs from conventional techniques, potentially involving charge transfer reactions less susceptible to competitive suppression from matrix components [27].

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Matrix Effect Management

| Solution Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Preparation | Primary-Secondary Amine (PSA), Enhanced Matrix Removal-Lipid (EMR), C18 sorbents | Remove phospholipids, fatty acids, and other interfering compounds during sample cleanup [27] |

| Internal Standards | Stable Isotope-Labeled Analytes (SIL-IS), IROA Internal Standard (IROA-IS) | Compensate for ionization suppression/enhancement through co-elution with identical properties [26] [31] |

| Chromatographic | Mixed-mode columns, HILIC columns, ion-pairing reagents | Alter separation selectivity to resolve analytes from matrix interferences [29] [32] |

| Ionization | Formic acid, ammonium formate, ammonia mobile phase additives | Enhance ionization efficiency; control adduct formation; improve chromatographic peak shape [29] [27] |

Emerging Trends and Future Perspectives

The landscape of matrix effect management continues to evolve with technological advancements in mass spectrometry and analytical methodologies. Recent innovations showcased at the 2025 American Society of Mass Spectrometry (ASMS) conference highlighted trends toward improved workflow efficiency, instrument miniaturization without performance compromise, and enhanced capabilities for top-down analysis of intact proteins [33]. These developments include novel ionization sources, improved instrument diagnostics, and smart analytics to address system inconsistencies [33].

The integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning (AI/ML) features in data analysis software represents a promising direction for more automated and intelligent matrix effect compensation [33]. These approaches may enable real-time correction and more sophisticated normalization strategies beyond current capabilities. Additionally, the continued development of alternative ionization sources like FμTP that demonstrate inherently reduced susceptibility to matrix effects suggests a future where analytical techniques may become more robust to matrix challenges rather than relying solely on compensation approaches [27].

The IROA TruQuant Workflow exemplifies the trend toward comprehensive, systematic solutions to the ion suppression problem, particularly for non-targeted analyses [31]. By providing a universal approach to correct ion suppression across diverse analytical conditions and biological matrices, this methodology addresses a long-standing limitation in metabolomics and other omics fields [31]. As these technologies mature and become more widely adopted, the analytical community may achieve unprecedented levels of quantitative accuracy and reproducibility in complex matrices, ultimately enhancing the reliability of LC-MS across pharmaceutical, clinical, and environmental applications.

Matrix effects remain a pervasive challenge in LC-MS analyses, significantly impacting the quality and reliability of quantitative results across diverse application areas. Understanding the fundamental mechanisms underlying ion suppression and enhancement—including competitive ionization, changes in droplet properties, and gas-phase proton transfer reactions—provides the foundation for effective mitigation strategies. Comprehensive detection and evaluation through methods such as post-column infusion and post-extraction spike experiments enable researchers to identify and quantify these effects during method development.

A multi-pronged approach combining selective sample preparation, optimized chromatographic separation, appropriate ionization source selection, and effective internal standardization represents the most effective strategy for managing matrix effects. While complete elimination is often impossible, particularly in complex matrices, the combination of these approaches with emerging technologies including alternative ionization sources and advanced computational correction methods continues to improve analytical performance. As mass spectrometry technologies evolve toward greater sensitivity, speed, and robustness, matrix effect management will remain an essential consideration in method development and validation to ensure data quality and regulatory compliance.

In liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS), the journey of an analyte from a dissolved molecule to a detectable gas-phase ion is complex and fraught with potential losses. The overall ion utilization efficiency—defined as the proportion of analyte molecules in solution that are successfully converted into detected gas-phase ions—is a critical metric of instrument performance [34]. This efficiency is not governed by a single component but is a cascade of processes, each with its own potential for ion discrimination or loss [34]. Two fundamental areas exert paramount influence: the ion source geometry, where the initial ionization and droplet formation occur, and the ion optics, the system of electrostatic lenses and guides that transport and focus the ion beam into the mass analyzer [34]. The design and configuration of these elements directly impact key performance parameters, including sensitivity, robustness, and the accuracy of quantitative analysis, especially for complex mixtures [7] [35]. This guide examines the foundational impact of these components within the broader context of factors affecting ionization efficiency in LC-MS research.

Ion Source Geometries and Interface Designs

The ion source and initial interface are the first and one of the most critical stages in determining the ultimate sensitivity of an LC-MS system. Their primary function is to efficiently generate ions from the LC effluent and transmit them from atmospheric pressure into the high vacuum of the mass spectrometer.

Conventional ESI-MS Interfaces

The conventional electrospray ionization (ESI) interface typically employs a single metallic inlet capillary, heated to aid droplet desolvation. The ESI emitter is positioned close ( ~2–3 mm) to this sampling inlet [34]. A significant limitation of this design is the restricted conductance of the single capillary and the inherent ion losses on its inner surfaces and at subsequent apertures [34]. To quantify this, researchers have measured the transmitted ion current through the interface and correlated it with the observed signal in the mass spectrum. A multi-capillary inlet, consisting of several capillaries arranged in a bundle, represents one approach to increase the total sampling area and thus the transmitted ion current [34].

The SPIN-MS Interface

A paradigm shift in interface design is the Subambient Pressure Ionization with Nanoelectrospray (SPIN) interface. This configuration removes the sampling capillary entirely by placing the nanoESI emitter directly within the first vacuum stage of the mass spectrometer (at a pressure of ~20 Torr), adjacent to the entrance of an electrodynamic ion funnel [34]. This removal of the atmospheric-vacuum barrier dramatically improves ion transmission. Experimental comparisons show that the SPIN-MS interface exhibits greater ion utilization efficiency than a conventional ESI-MS interface [34]. The gains are most pronounced when the SPIN interface is coupled with a brighter ion source, such as an ESI emitter array, demonstrating that improvements in ion production are only fully realized when paired with a high-transmission interface [34].

Vaporization Micro-Channel in LEI

In alternative ionization techniques like Liquid Electron Ionization (LEI), the design of the vaporization region is equally critical. The vaporization micro-channel (VMC) is responsible for the nebulization and complete vaporization of the liquid flow before it reaches the electron ionization source [36]. Studies optimizing the LEI interface have tested different VMC capillary internal diameters (I.D.) and materials. For instance, moving from a 400 µm I.D. silica VMC capillary to a 500 µm I.D. one improved detectability, achieving limit of detection (LOD) values almost five times lower for some analytes [36]. The use of a deactivated silica capillary further enhanced performance by improving inertness, reducing gas-phase interactions, and minimizing analyte deposition [36].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of LC-MS Interface Geometries

| Interface Type | Key Feature | Measured Advantage | Potential Drawback |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single Capillary Inlet [34] | Single heated metal capillary | Standard, robust design | Restricted ion transmission; significant losses |

| Multi-Capillary Inlet [34] | Bundle of seven inlet capillaries | Increased total transmitted ion current | More complex manufacturing and alignment |

| SPIN Interface [34] | Emitter inside vacuum; no capillary | Highest measured ion utilization efficiency | Requires modification of MS vacuum chamber |

| LEI with Optimized VMC [36] | 500 µm I.D. deactivated silica capillary | LODs ~5x lower for some PAHs/pesticides | Specific to LEI systems; requires flow splitting |

Ion Optics and Instrumental Settings

Once ions pass through the initial interface, their trajectory through the ion optics system is crucial. In an ESI-ion trap mass spectrometer, this system typically consists of a series of skimmers, octopoles, and lenses, culminating in the ion trap itself. The DC and RF voltages applied to these components must be carefully tuned to transmit and focus ions across a broad mass range without discrimination.

Key Parameters in ESI-Ion Trap MS

The following parameters in an ESI-IT-MS system have been quantitatively shown to significantly impact ion transmission and detection, particularly for accurate relative quantification [35] [37]:

- Capillary Exit (Cap Exit) Voltage: This voltage, applied at the exit of the transfer capillary, accelerates ions into the subsequent vacuum stage. It is crucial for declustering but can also induce in-source fragmentation. Its setting is especially critical for the transmission and accurate quantification of low m/z ions [35] [37].

- Octopole DC and RF Voltages: The octopoles guide and focus the ion beam. The DC voltage (especially Oct 2 DC) and RF amplitude (Oct RF) significantly impact absolute and relative ion intensities. An equation has been established to describe the relationship between Oct 2 DC, m/z, and the optimal Trap Drive voltage, allowing for the calculation of settings that prevent m/z-based discrimination [35].

- Trap Drive (TD): This is the amplitude of the RF voltage applied to the ring electrode of the ion trap. It controls the stability of ion trajectories within the trap and is profoundly mass-dependent. The Trap Drive at maximum intensity (TDmax) for an ion is a key parameter for optimization [35].

Impact on Quantitative Accuracy

The need for precise control of these settings is starkly illustrated in the quantitative analysis of isotopologous compounds, such as in cellulose ether analysis. Using equimolar binary mixtures of per-O-methyl and per-O-deuteromethyl cellooligosaccharides, researchers found that standard, non-optimized "smart" settings led to a clear decrease in the intensity ratio of the deuterated to non-deuterated isotopologs with increasing degree of polymerization (DP)—a clear sign of m/z discrimination [37]. However, by individually optimizing the Cap Exit, Oct 2 DC, and TD for each DP, this trend was eliminated. The measured intensity ratios became consistent across DP 2–6, ranging between 0.971 and 1.040, thereby enabling accurate relative quantification [37].

Table 2: Impact of Key Ion Optics Parameters on Quantitative Analysis

| Instrumental Parameter | Primary Function | Impact on Analysis | Optimization Finding |

|---|---|---|---|

| Capillary Exit Voltage [35] [37] | Ion acceleration & declustering | Critical for low m/z ion transmission; can cause fragmentation | Essential for correct quantification of small molecules/DP2 oligosaccharides |

| Octopole 2 DC Voltage [35] | Ion beam guidance & focusing | Major impact on absolute ion intensity and m/z discrimination | Linked to m/z and Trap Drive; an optimization equation was established |

| Trap Drive (TD) [35] [37] | Controls ion stability in trap | Mass-dependent storage efficiency; key for relative signal accuracy | TDmax must be determined and set for the target m/z to avoid bias |

| Compound Stability / Target Mass [37] | Automated setting of Cap Exit & optics | Can introduce significant m/z bias in relative quantification | Manual "expert mode" optimization is required for precise work |

Experimental Protocols for Instrument Evaluation

To systematically evaluate and optimize ion source and ion optics performance, researchers can employ the following detailed experimental protocols, derived from recent studies.

This method quantifies the overall efficiency of an ESI-MS interface by correlating transmitted electric current with the observed MS signal [34].

- Solution Preparation: Prepare a 1 µM solution of a standard peptide (e.g., angiotensin I) in 0.1% formic acid in 10% acetonitrile.

- Interface Configuration: Set up the interface to be tested (e.g., single capillary, multi-capillary, or SPIN).

- Current Measurement: Use a picoammeter to measure the total electric current of ions transmitted through the high-pressure ion funnel. This current includes both desolvated ions and residual charged clusters.

- MS Measurement: Simultaneously, acquire a mass spectrum and extract the total ion current (TIC) or the extracted ion current (EIC) for the analyte.

- Efficiency Calculation: The ratio of the MS-measured ion current (a measure of "useful" desolvated ions) to the total transmitted electric current provides a metric of the interface's ion utilization efficiency. A higher ratio indicates more effective desolvation and transmission of gas-phase ions [34].

Protocol 2: Optimizing Ion Optics for Relative Quantification

This protocol is designed to eliminate m/z-based discrimination during relative quantification, as used in the analysis of cellulose ethers [35] [37].

- Sample Preparation: Synthesize or obtain equimolar binary mixtures of analytes with a constant mass difference. Examples include:

- Syringe Pump Infusion: Directly infuse the binary mixture at a concentration of 10⁻⁶ M in a suitable solvent via a syringe pump, bypassing the LC system to isolate MS effects.

- Parameter Screening (Expert Mode): Operate the mass spectrometer in "expert mode" to directly control key voltages.

- Systematically vary the Cap Exit voltage for the lowest DP/smallest m/z analyte to maximize signal without inducing fragmentation [37].

- For a range of m/z values, systematically vary the Oct 2 DC and Trap Drive (TD) voltages. For each combination, record the intensity of the target ions.

- Data Analysis and Model Application:

- For each m/z, identify the Trap Drive at maximum intensity (TDmax).

- Establish a mathematical relationship (e.g., linear or logarithmic) between m/z, Oct 2 DC, and TDmax. This model can then be used to predict optimal settings for other m/z values [35].

- Validation: Measure the intensity ratio of the binary mixture under optimized conditions. The result should be close to 1.0 and show no consistent trend with m/z or concentration, confirming the elimination of instrumental bias [37].

Visualization of Ion Pathways and Optimization Workflow

The following diagrams, generated using Graphviz, illustrate the core concepts and experimental workflows described in this guide.

ESI-MS Ion Transmission Pathway

Ion Optics Optimization Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details key reagents and materials used in the foundational experiments cited, which are essential for conducting similar optimization and evaluation studies.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Ionization Efficiency Studies

| Item Name | Specification / Example | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|---|

| Metabolite/Peptide Standards [7] [34] | Human angiotensin I, bradykinin, commercial metabolite library | Model analytes for testing sensitivity, ionization efficiency, and ion transmission. |

| Isotopologous Analytes [37] | Per-O-Me-/Per-O-Me-d₃ cellooligosaccharides | Critical for quantifying m/z discrimination in relative quantification without chemical bias. |

| Labeling Reagents [35] | m-Aminobenzoic acid (mABA) | Introduces a fixed charge to carbohydrates for controlled ionization, improving quantitative accuracy. |

| Etched Fused Silica Emitters [34] | O.D. 150 µm, I.D. 10 µm, chemically etched | NanoESI emitters for stable, high-efficiency ion production at low flow rates. |

| Deactivated Silica Capillaries [36] | e.g., Agilent CP805310 | Used in vaporization regions (e.g., LEI-VMC) to improve inertness, reduce analyte interaction, and enhance detectability. |

| Syringe Pump [34] [37] | e.g., Harvard Apparatus Model 22 | For direct infusion experiments, allowing isolation of MS performance from LC separation effects. |

Strategic Method Development: Practical Approaches to Control Ionization Efficiency

In Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS), the path to reliable data begins long before the sample is injected into the instrument. The ionization efficiency of an analyte within the mass spectrometer's ion source is the pivotal determinant of sensitivity and signal robustness. This efficiency, however, is profoundly susceptible to compromise by co-eluting matrix components, a phenomenon known as ion suppression or matrix effects [24]. Sample preparation serves as the first and most crucial line of defense against these detrimental effects. It is not merely a preliminary step but a foundational strategy to ensure that ionization occurs in an unobstructed manner, leading to accurate quantification, superior detection limits, and robust method performance [38] [39]. This guide details the core techniques of Solid-Phase Extraction (SPE), Protein Precipitation (PPT), and matrix-specific cleanup, framing them within the essential context of safeguarding ionization efficiency in LC-MS research.

The Ionization Process and the Problem of Matrix Effects

Mechanisms of Ion Suppression

In electrospray ionization (ESI), the most common LC-MS interface, ion suppression occurs when non-analyte molecules in the sample co-elute and interfere with the efficient ionization of the target compound [40]. These interfering substances, which can include salts, phospholipids, metabolites, or residual proteins, compete for available charge or disrupt the droplet formation and desolvation processes at the ion source [41] [24]. The consequences are dire: a suppressed or enhanced analyte signal, reduced sensitivity, poor precision, and inaccurate quantification [24] [39]. Evidence suggests that ion suppression is more pronounced in ESI than in Atmospheric Pressure Chemical Ionization (APCI) because the ionization process in ESI occurs in the condensed phase before droplets enter the gas phase, making it more vulnerable to competing species [24].

The Strategic Imperative of Sample Cleanup

The primary goal of advanced sample preparation is to remove these interfering matrix components. A well-designed cleanup protocol directly enhances ionization efficiency by reducing the "noise" of the chemical background, thereby allowing the "signal" of the analyte's ionization to proceed unimpeded. This is not an optional refinement but a necessity for methods analyzing complex matrices like plasma, urine, or tissue homogenates, where the chemical background is rich and variable [38]. By implementing techniques like SPE and PPT, researchers can directly mitigate the risk of ion suppression, turning an unpredictable analysis into a controlled and reliable one.

Core Sample Preparation Techniques

Solid-Phase Extraction (SPE)

SPE is a highly versatile and selective sample preparation technique that utilizes a solid sorbent to isolate and concentrate analytes from a liquid sample. Its principle is based on the partitioning of compounds between a solid and a liquid phase, where analytes are retained on the sorbent based on specific chemical interactions and then eluted using a solvent that disrupts those interactions [42].

Experimental Protocol: A Generic SPE Procedure

The typical SPE procedure consists of five critical steps [42]:

- Sorbent Activation/Conditioning: The sorbent bed is treated with a strong solvent (e.g., methanol) to solvate the functional groups, followed by a weak solvent (e.g., water or buffer) that mimics the sample matrix. This prepares the sorbent surface for optimal analyte retention.

- Sample Loading: The prepared sample is passed through the cartridge. Analytes of interest are retained on the sorbent while some matrix interferences flow through.

- Washing: A wash solvent with weak elution strength is applied to remove weakly adsorbed matrix components without displacing the analytes. This is a key step for reducing ion suppression.

- Elution: The analytes are desorbed from the sorbent and collected using a small volume of a strong, volatile solvent that has a greater affinity for the analytes.

- Sample Reconstitution: The eluate is often evaporated to dryness and the residue is reconstituted in a solvent compatible with the LC-MS starting mobile phase, serving to concentrate the sample and improve sensitivity.

Sorbent Chemistry and Selection

The selectivity of SPE is governed by the chemistry of the sorbent. Choosing the correct sorbent is paramount for success. The table below summarizes common sorbent types and their applications.