Maximizing Ionization Efficiency in Small Molecule Analysis: Strategies for Enhanced Sensitivity and Accuracy in Mass Spectrometry

This article provides a comprehensive overview of ionization efficiency, a critical factor determining the sensitivity and accuracy of small molecule analysis in mass spectrometry.

Maximizing Ionization Efficiency in Small Molecule Analysis: Strategies for Enhanced Sensitivity and Accuracy in Mass Spectrometry

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of ionization efficiency, a critical factor determining the sensitivity and accuracy of small molecule analysis in mass spectrometry. Covering foundational principles, advanced methodologies, common challenges, and validation techniques, it explores innovative materials like black phosphorus and covalent organic frameworks as next-generation matrices. It details strategies to overcome pervasive issues like ion suppression and discusses emerging trends such as post-ionization and machine learning. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, this review serves as a strategic guide for optimizing analytical workflows in biomedical research, clinical diagnostics, and pharmaceutical development.

The Fundamentals of Ionization: Unraveling the Core Principles for Small Molecules

Defining Ionization Efficiency and Its Impact on Detection Limits

Ionization efficiency is a fundamental parameter in mass spectrometry (MS), defined as the ability of a technique to effectively convert analyte molecules into gaseous ions that can be detected and analyzed [1]. This efficiency is a critical performance determinant for MS instruments, particularly in the analysis of small molecules, as it directly governs the number of ions available for detection [1]. Higher ionization efficiency results in a greater number of analyte ions being generated, which subsequently improves the signal-to-noise ratio and lowers the method's detection limits [1]. The choice of ionization technique—such as electron ionization (EI) versus electrospray ionization (ESI)—significantly impacts the ionization efficiency for a particular analyte, influenced by factors including analyte polarity, molecular structure, and the presence of specific functional groups [1].

Quantitative Relationship Between Ionization Efficiency and Detection Limits

The core relationship between ionization efficiency and detection limits is direct and pivotal. Ionization efficiency is a key factor determining the sensitivity and detection limits of a mass spectrometry method [1]. When ionization efficiency is high, a larger proportion of the neutral analyte molecules are converted into charged ions. This increased population of ions leads to a stronger analytical signal. The impact on the signal-to-noise ratio is profound: a stronger signal relative to the background noise allows for more confident detection and quantification of analytes present at very low concentrations. Consequently, methods with high ionization efficiency can achieve lower detection limits, enabling scientists to detect trace-level compounds that would otherwise remain unseen [1].

Table 1: Factors Influencing Ionization Efficiency and Their Impact on Detection

| Factor | Impact on Ionization Efficiency | Consequence for Detection Limits |

|---|---|---|

| Analyte Polarity | Polar compounds typically show higher efficiency in electrospray ionization (ESI). | Lower detection limits achievable for polar molecules in ESI-MS. |

| Molecular Structure | Presence of ionizable functional groups (e.g., -COOH, -NH₂) enhances efficiency. | Detection limits vary significantly across chemical classes based on structure. |

| Ionization Technique | "Soft" techniques like ESI often yield higher efficiency for intact molecules than "hard" techniques like EI. | Technique selection is critical for achieving optimal detection limits for a given analyte. |

| Source Conditions | Parameters like voltage, temperature, and gas flow rates can be optimized to maximize efficiency [1]. | Proper optimization directly improves sensitivity and lowers detection limits. |

| Eluent Composition | Solvent pH, buffer concentration, and organic modifier affect ionization yield [2]. | Consistency in mobile phase is essential for stable detection limits. |

Experimental Protocols for Measuring and Studying Ionization Efficiency

Relative Ionization Efficiency Measurement via Flow Injection

A common approach for determining ionization efficiency involves flow injection analysis to calculate a relative logIE value [3].

Protocol Steps:

- Solution Preparation: Prepare a series of six dilutions (e.g., 1-, 1.25-, 1.67-, 2-, 2.5-, and 5-fold) of the analyte stock solution and an anchor compound (e.g., tetraethylammonium for positive mode; benzoic acid for negative mode) using the relevant LC eluent [3].

- Flow Injection Analysis: Inject the diluted solutions (e.g., 10 µL injection volume) directly into the MS via a flow injection at a constant flow rate (e.g., 0.2 mL/min), bypassing any chromatographic column [3].

- Data Acquisition: Record the responses (peak intensities) for the [M+H]⁺ (or [M-H]⁻) ions of both the analyte and the anchor compound in full-scan MS mode. If in-source fragmentation occurs, sum the intensities of the fragment ion peaks with the molecular ion peak [3].

- Calculation of Relative Ionization Efficiency (RIE): For each compound, perform a linear regression of the signal intensity versus concentration within the linear dynamic range. The RIE of analyte M₁ relative to anchor compound M₂ is calculated using the formula:

RIE(M₁/M₂) = [slope(M₁) * Isotopic Contribution(M₁)] / [slope(M₂) * Isotopic Contribution(M₂)][3].

- Establishing the logIE Scale: Convert the RIE to a logarithmic scale (logIE) for easier comparison, anchored to the known logIE value of the reference compound:

logIE(M₁) = log RIE(M₁/M₂) + logIE(anchor)[3].

Investigating Positional Isomers in Phosphatidylcholines

Specialized protocols are required to study subtle effects on ionization efficiency, such as those caused by structural isomerism.

Protocol Steps:

- Synthesis and Purification: Chemically synthesize the target positional isomers (e.g., PC(22:6/16:0) and PC(16:0/22:6)). Purify the synthesized standards using techniques like recycling preparative HPLC to achieve high isomeric purity (>99%) [4].

- Absolute Quantification of Standards: Employ quantitative NMR (qNMR) for accurate concentration determination of the stock standard solutions, using a certified internal standard (e.g., 1,4-bis(trimethylsilyl)benzene-d₄) to avoid errors from potential degradation during solvent evaporation [4].

- LC-MS/MS Analysis: Analyze the accurately quantified standards using reversed-phase LC-MS/MS. The mobile phase typically consists of water and acetonitrile, both with additives like ammonium formate, using a gradient elution [4].

- Data Comparison: Compare the MS response (peak area) of the two isomers when injected at identical known concentrations. A higher signal for one isomer under the same conditions demonstrates its higher ionization efficiency [4].

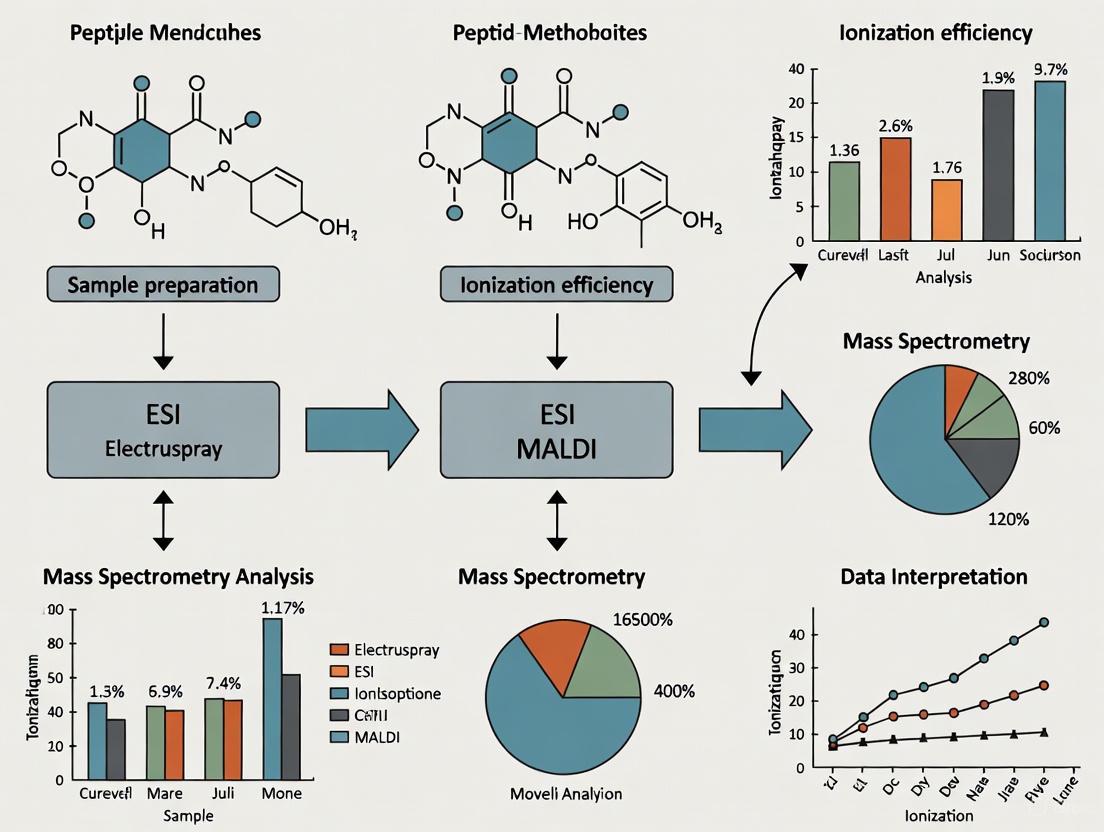

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for measuring relative ionization efficiency using flow injection-MS.

Factors Affecting Ionization Efficiency and Experimental Optimization

Molecular Properties and Structural Effects

The intrinsic properties of the analyte molecule are primary determinants of its ionization efficiency.

Chemical Structure and Functional Groups: The presence of readily ionizable functional groups (e.g., amines, carboxylic acids) fundamentally enhances efficiency. Furthermore, specific structural features can have pronounced effects. For instance, in electrospray ionization, the polarity of a molecule is a major driver of its ionization efficiency [2]. A striking example is found in phosphatidylcholine (PC) positional isomers. Research has demonstrated that PC(22:6/16:0) exhibits a higher ionization efficiency compared to its isomer PC(16:0/22:6), proving that the position of a docosahexaenoic acid chain on the glycerol backbone directly impacts the ionization yield [4].

Ion Suppression and Competition: Ionization efficiency is not an absolute property measured in isolation. In complex mixtures, analytes compete for charge during the ionization process. This phenomenon, known as ion suppression, occurs when the ionization of one analyte is hindered by the presence of another, often more efficiently ionizing, compound [5]. The degree of suppression is influenced by factors like relative concentration and affinity for charge.

Instrumental and Operational Parameters

Instrumental settings and the chemical environment can be optimized to maximize ionization efficiency.

Ionization Source Geometry and Flow Rate: The design of the ESI source and the flow rate of the liquid introduced into it are critical. Operating at ultra-low flow rates (e.g., in the tens of nL/min range) significantly enhances ionization efficiency and reduces ion suppression. This is because lower flow rates produce smaller initial droplets, which have a higher surface-to-volume ratio, leading to more efficient desolvation and ion release [5]. Studies have shown that ion suppression can become practically negligible at flow rates around 20 nL/min [5].

Eluent Composition: The composition of the mobile phase strongly influences ionization yield. Parameters such as pH, the presence of volatile buffers (e.g., ammonium formate), and the type and proportion of organic modifier (e.g., acetonitrile, methanol) can alter the analyte's protonation/deprotonation state and the droplet's surface tension, thereby affecting ionization efficiency [2] [3].

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Ionization Efficiency Studies

| Reagent / Solution | Function in Experiment | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Anchor Compounds | Provides a reference point for measuring relative ionization efficiency (RIE). | Tetraethylammonium (ESI+), Benzoic Acid (ESI-) [3]. |

| qNMR Internal Standard | Enables absolute quantification of synthesized standard concentrations without reliance on gravimetry. | 1,4-bis(trimethylsilyl)benzene-d₄ (BTMSB-d₄) [4]. |

| Volatile Buffers | Modifies eluent pH and ionic strength without causing source contamination or ion suppression. | Ammonium Formate, Ammonium Acetate, Formic Acid [6] [4]. |

| Isotopically Labeled Standards | Used for standard addition or internal standardization to correct for matrix effects and signal variability. | Not explicitly listed, but is a cornerstone of quantitative MS. |

| Synthetic Isomer Standards | Allows for direct experimental comparison of ionization efficiencies between specific structural variants. | Synthesized PC(22:6/16:0) and PC(16:0/22:6) [4]. |

Advanced Applications: Machine Learning and High-Throughput Screening

Predicting Efficiency with Machine Learning

A major challenge in non-targeted analysis is the quantification of compounds without authentic standards. Machine learning (ML) has emerged as a powerful tool to address this by predicting ionization efficiency (IE) based on molecular structure.

Model Training and Application: ML models, such as extreme gradient boosting (xgBoost), are trained on datasets containing known logIE values and numerical descriptors of chemical structure (e.g., PaDEL descriptors) [2]. The trained model can then predict the logIE of an unknown compound based solely on its structural features. This predicted IE value allows researchers to estimate the compound's concentration directly from the MS signal intensity, bypassing the need for a physical standard [3]. This approach has been validated, showing the ability to predict compound response with a mean error of approximately 2.0–2.2 times in scientific studies [3].

Active Learning for Enhanced Prediction: A significant limitation of ML models is that their predictive accuracy drops for chemicals that are structurally dissimilar to those in the training set. Active learning (AL) is a strategic iterative process that improves model performance. It identifies the most "informative" data points (i.e., chemicals from the under-represented chemical space) to be measured next [2]. By experimentally determining the IE of these selected compounds and adding them to the training data, the model's applicability domain is expanded efficiently. This process has been shown to significantly reduce prediction errors and improve quantification accuracy in real-world applications, such as quantifying natural products in complex extracts [2].

Figure 2: Active learning cycle for improving machine learning models that predict ionization efficiency.

Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization Mass Spectrometry (MALDI-MS) is a powerful analytical technique renowned for its high-throughput capability and broad molecular coverage. However, its effectiveness, particularly for small molecule analysis, is critically challenged by two interconnected phenomena: background interference (or matrix effects) and the low-mass barrier. Background interference refers to the suppression of analyte ionization due to the complex chemical environment of the sample, which can lead to significant quantitative inaccuracies. The low-mass barrier describes the inherent difficulty in detecting low molecular weight compounds (typically below m/z 500) due to intense and overlapping signals from the MALDI matrix itself. Within the broader thesis of optimizing ionization efficiency for small molecule analysis, overcoming these hurdles is paramount for achieving precise, reproducible, and quantitatively reliable data. This guide details the mechanistic origins of these challenges and presents advanced, validated experimental protocols designed to mitigate them.

The Fundamental Challenges in Detail

Background Interference and Ion Suppression

Background interference in MALDI-MS arises from the complex, heterogeneous nature of biological samples. This "matrix effect" is not to be confused with the chemical matrix, but rather refers to the suppression of analyte ionization by co-localized compounds in the tissue. These can include salts, cell debris, lipids, and other endogenous molecules that compete for the available charge during the ionization process [7] [8]. The consequence is a non-linear relationship between the actual analyte concentration and the detected signal intensity, severely hampering precise quantitation. This effect is spatially variable; for instance, in brain tissue, the distinct chemical compositions of gray matter (densely packed neurons) and white matter (myelinated axons) create regions with vastly different ionization efficiencies, making it difficult to compare analyte levels across different anatomical structures directly [8].

The Low-Mass Barrier for Small Molecules

The analysis of small polar metabolites—such as those involved in the TCA cycle, glycolysis, and amino acid metabolism (m/z < 500)—faces a distinct set of challenges. Their low molecular weight places them directly in the spectral region dominated by matrix-related ions, leading to poor detection sensitivity and coverage [9]. Furthermore, these metabolites are highly water-soluble, making them prone to delocalization during sample preparation washes, which distorts their native spatial distribution [9]. Their intrinsic poor ionization efficiencies compared to larger, more abundant biomolecules like lipids further exacerbate the problem, as they are easily suppressed in complex mixtures [9].

Table 1: Core Challenges in MALDI-MS for Small Molecule Analysis

| Challenge | Primary Cause | Impact on Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Background Interference / Matrix Effects | Co-localized compounds (salts, lipids, debris) in the sample suppressing analyte ionization [8]. | Reduces quantitative accuracy; causes spatial variability in signal intensity [8]. |

| Low-Mass Barrier | Intense spectral peaks from the MALDI matrix itself cluttering the low m/z region [9]. | Obscures detection of small analytes (m/z < 500); limits sensitivity and metabolome coverage [9]. |

| Analyte Delocalization | Solubility of small polar metabolites in aqueous/organic solvents used during sample preparation [9]. | Compromises spatial integrity; molecular images do not reflect true biological localization. |

Advanced Experimental Protocols for Mitigation

Protocol: A Basic Hexane Wash for Enhanced Polar Metabolite Imaging

This optimized solvent pretreatment method significantly improves the sensitivity and coverage of polar and stable isotope-labeled (SIL) metabolites by reducing ion suppression from lipids and proteins [9].

Detailed Methodology:

- Tissue Sectioning: Prepare 12 μm thick fresh frozen tissue sections from the target organ (e.g., kidney, liver, brain, heart) and thaw-mount onto ITO-coated glass slides or PEN membrane slides for subsequent validation. Vacuum-desiccate for 20 minutes [9].

- Wash Solution Preparation: Prepare the "basic hexane" solution immediately before use to minimize phase separation. The mixture is 997 μL of hexane, 1 μL of 28% aqueous ammonia (0.1%), and 2 μL of chloroform (0.2%). The chloroform acts as a cosolvent to ensure even distribution of the basic modifier in the organic solvent [9].

- Wash Procedure: Pipette 100 μL of the freshly prepared basic hexane solution onto the tissue section. After 5 seconds of exposure, incline the slide to remove the solvent. Repeat this process five times for a total solvent volume of 500 μL, ensuring even tissue coverage [9].

- Post-Wash Desiccation: Place the slide in a vacuum desiccator for 20 minutes to ensure complete drying [9].

- Matrix Application: Apply the matrix, (1-naphthyl)ethylenediamine dihydrochloride (NEDC), at a concentration of 7 mg/mL in a solvent mixture of 70:25:5 MeOH/ACN/H₂O (v/v/v). Use an automated sprayer (e.g., SunCollect MALDI sprayer) for homogeneous coverage [9].

Spatial Validation via LMD-LC-MS/MS: A critical concern with any wash protocol is analyte delocalization. To spatially validate the results:

- Collect consecutive tissue sections mounted on PEN membrane slides and apply the basic hexane wash.

- Use a Laser Microdissection (LMD) system to excise specific regions of interest (e.g., cortex, medulla in kidney) based on the MALDI-MSI images.

- Perform LC-MS/MS metabolomic analysis on the excised tissues to quantify metabolites.

- Statistically compare the regional intensities from LMD-LC-MS/MS with those extracted from the MALDI-MSI data to confirm spatial fidelity [9].

This method has been shown to improve sensitivity for a broad range of polar metabolites by several-fold across multiple mouse organ tissues [9].

Protocol: Standard Addition Method for Quantitative Neurotransmitter Imaging

This protocol uses a homogeneous spraying technique for standards to account for spatial matrix effects, enabling accurate quantification of neurotransmitters in complex and heterogeneous tissues like the brain [8].

Detailed Methodology:

- Tissue Preparation: Cut 12 μm thick sagittal brain tissue sections and mount them centrally on ITO slides with sufficient distance between sections to prevent cross-contamination [8].

- Spraying Internal Standard for Normalization:

- Prepare stock solutions of stable isotope-labeled (SIL) internal standards (e.g., DA-d₄, 3-MT-d₃, NE-d₆) in 50% MeOH.

- Use a robotic sprayer (e.g., TM-sprayer, HTX Technologies) with calibrated parameters (nozzle temp: 90°C, flow rate: 70 μL/min, velocity: 1100 mm/min, pressure: 6 psi, track spacing: 2.0 mm) to homogeneously apply the SIL standards over all tissue sections in six passes. This achieves a consistent concentration (e.g., 7.2 pmol/mg tissue) across the entire sample for signal normalization [8].

- Spraying Calibration Standards (Two Methods):

- Method A (Native Calibrants): Cover all but one tissue section with a coverslip. Spray a series of known concentrations of the native target analytes (e.g., DA, NE, 3-MT) onto the single exposed section. Repeat for consecutive sections with different standard concentrations [8].

- Method B (SIL Calibrants): A more advanced approach uses a second set of SIL analogues (e.g., DA-¹³C₆) as calibration standards, which are sprayed homogenously over the entire tissue section. The endogenous native analytes are then quantified against this calibration curve [8].

- Matrix Application: Apply a derivatizing MALDI matrix, FMP-10 (4.4 mM in 70% acetonitrile), using the robotic sprayer (20 passes) [8].

- Data Acquisition and Quantification:

- Acquire MALDI-MSI data in positive ion mode.

- Extract signal intensities for the analytes and their corresponding internal standards from specific regions (e.g., striatum).

- For Method A, plot the normalized signal intensity against the amount of standard added for each consecutive section. The endogenous concentration is determined by the x-intercept of the resulting calibration curve, which typically shows strong linearity (R² > 0.99) [8].

This standard addition approach has demonstrated results comparable to those obtained by HPLC-ECD, confirming its quantitative accuracy [8].

Diagram 1: Integrated workflow for quantitative MALDI-MSI of small molecules.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

The following table lists key materials and their specific functions in addressing the challenges discussed in this guide.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Advanced MALDI-MS

| Reagent / Material | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|

| NEDC Matrix | (1-naphthyl)ethylenediamine dihydrochloride; a matrix particularly effective for imaging small polar metabolites in the low-mass range (m/z < 500) [9]. |

| Basic Hexane Wash | A solvent pretreatment (Hexane + 0.1% NH₄OH + 0.2% CHCl₃) that reduces ion suppression from lipids and proteins, enhancing sensitivity for polar metabolites [9]. |

| Stable Isotope-Labeled (SIL) Analogs | Deuterated or ¹³C-labeled versions of target analytes. Used as internal standards for signal normalization and for creating calibration curves to correct for matrix effects [8]. |

| FMP-10 Matrix | A derivatizing matrix used for the sensitive detection and quantification of neurotransmitters like dopamine and norepinephrine in positive ion mode [8]. |

| ITO-Coated Glass Slides | Provide a conductive surface necessary for MALDI-MS analysis while allowing for optical microscopy on the same slide [10]. |

| PEN Membrane Slides | Used for Laser Microdissection (LMD) to excise regions of interest for downstream LC-MS/MS validation of spatial distributions [9]. |

| Robotic Sprayer | (e.g., TM-Sprayer). Enables homogeneous, quantitative, and reproducible application of matrices, standards, and solvents, which is critical for reliable quantification [8]. |

Background interference and the low-mass barrier represent significant, yet surmountable, obstacles in the path of achieving high-fidelity small molecule analysis using MALDI-MS. The root of these challenges lies in the complex interplay of ionization efficiency and the sample's chemical environment. As detailed in this guide, the solutions are not merely incremental adjustments but fundamental shifts in methodology. The adoption of robust solvent washes, such as the basic hexane method, directly combats ion suppression. Furthermore, the implementation of quantitative frameworks based on the standard addition method with homogeneously sprayed SIL standards is a decisive step toward overcoming spatial matrix effects for true quantitation. When combined with spatial validation techniques like LMD-LC-MS/MS, these protocols provide a comprehensive strategy to unlock the full potential of MALDI-MS, transforming it from a qualitative mapping tool into a robust platform for spatially resolved, quantitative small molecule analysis.

The SALDI Revolution: Inorganic Nanomaterials as Alternative Matrices

Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization Mass Spectrometry (MALDI-MS) is a cornerstone soft ionization technique for biomolecular analysis. However, its effectiveness drastically diminishes for small molecules (typically <900 Da) due to substantial background noise generated by the organic matrices themselves in the low-mass region. This interference has historically prevented MALDI-MS from realizing its potential in critical areas such as metabolomics, environmental monitoring, and pharmaceutical development [11] [12]. Surface-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization Mass Spectrometry (SALDI-MS) was developed to address this fundamental limitation. By replacing the organic matrix with inorganic nanomaterials of high physical and chemical stability, SALDI-MS effectively suppresses background noise, enabling the direct detection of small molecules [11] [13]. Despite this advantage, a key challenge remained: early SALDI substrates could not match the ionization efficiency of conventional MALDI, often resulting in lower sensitivity. The ongoing "SALDI revolution" is therefore centered on the rational design and engineering of advanced inorganic nanomaterials to not only eliminate background interference but also to significantly enhance ionization efficiency, thereby unlocking high-sensitivity analysis of small molecules in complex samples [11] [12].

Fundamental Mechanisms: How Nanomaterials Drive Ionization

The performance of a SALDI substrate hinges on its dual role as an analyte carrier and an energy receptor that absorbs laser energy and transfers it to analyte molecules for desorption and ionization [11]. Nanomaterials excel in this role due to their high surface area and tunable photophysical properties. The primary mechanisms behind their efficiency are localized surface plasmon resonance and efficient energy transfer.

Localized Surface Plasmon Resonance (LSPR) and "Hot Spots"

Plasmonic metallic nanoparticles (e.g., gold, silver) exhibit a unique phenomenon known as Localized Surface Plasmon Resonance (LSPR). When these nanoparticles are exposed to incident laser light, their local free electrons collectively oscillate. Upon relaxation, these excited electrons undergo ultrafast processes like electron-electron scattering, generating a substantial amount of heat, which is crucial for analyte desorption [11]. Concurrently, electrons above the Fermi level become "hot electrons" with excellent mobility, which can transfer to the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital of an adsorbed analyte molecule, promoting ionization [11]. The LSPR effect can be dramatically amplified by creating nanogaps between nanoparticles. When gaps are decreased, the local electromagnetic field experiences an exponential enhancement due to coupling between adjacent nanoparticles, creating regions known as "hot spots" [11] [14]. These hot spots provide more electrons and energy to boost laser desorption/ionization (LDI) efficiency. This principle has been leveraged in various nanostructure designs, including silica@gold core–shell materials with a nanogap-rich shell (SiO2@Au NGS), where the gap size is precisely controlled during synthesis to maximize the local electromagnetic field [14].

Energy Transfer and Desorption Processes

The process of LDI in SALDI-MS involves a complex interplay of energy absorption and transfer. The inorganic substrate must efficiently absorb the laser pulse's photon energy. In plasmonic nanoparticles, this is achieved via LSPR. The absorbed energy is then rapidly converted into thermal energy (heat) at the nanoparticle's surface, facilitating the rapid heating and desorption of the analyte molecules. This surface-generated heat plays a crucial role in activating analyte molecules to dissociate their bonds in the gas phase. Simultaneously, the charge transfer between the substrate and the analyte—such as the transfer of hot electrons—directly facilitates the ionization of the desorbed molecules, leading to the formation of ions like [M+H]+ or [M-H]- [11]. The synergy between efficient thermal desorption and charge-transfer ionization is key to achieving high LDI efficiency with inorganic nanomaterials.

Table 1: Key Ionization Mechanisms in SALDI-MS Using Nanomaterials

| Mechanism | Physical Process | Key Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Localized Surface Plasmon Resonance (LSPR) | Collective oscillation of free electrons in metal nanoparticles upon laser irradiation. | Enhanced electromagnetic field, generating heat and hot electrons. |

| Electromagnetic Field Enhancement | Coupling of electromagnetic fields in nanogaps ("hot spots") between nanoparticles. | Exponential signal amplification at the gaps between nanostructures. |

| Thermal Desorption | Ultrafast relaxation of excited electrons via electron-phonon coupling, generating heat. | Rapid heating and phase transition of analytes from solid to gas phase. |

| Hot Electron Transfer | Migration of excited "hot electrons" to the analyte's molecular orbitals. | Promotion of analyte ionization (e.g., formation of [M-H]- ions). |

A Guide to SALDI-Active Nanomaterials and Their Performance

The selection of the nanomaterial is critical for SALDI performance. Recent advancements have led to the development of a diverse array of substrates with tailored properties.

Plasmonic Metal Nanostructures

Noble metals like gold and silver are among the most widely studied SALDI materials due to their strong LSPR effects. A key advancement has been the move from simple nanoparticles to engineered nanostructures with controlled gaps. For instance, gold nanoshells with nanogaps (SiO2@Au NGS) have demonstrated superior performance. In one study, controlling the gold shell thickness to 17.2 nm resulted in the highest absorbance and optimal SALDI capability for analyzing amino acids, sugars, and flavonoids [14]. The limit of detection (LOD) for small molecules can reach the attomole range, with high reproducibility and salt tolerance [14]. Another strategy involves creating uniform films of gold nanoparticle (AuNP) arrays where the interstitial gaps are tuned by adjusting the ionic strength during electrostatic assembly. This method allows for the systematic investigation of the LSPR effect on LDI and has shown remarkable efficiency in detecting small biomolecules and dyes, as well as sulfonamides in complex lake water samples [11].

Carbon-Based and Two-Dimensional Materials

Carbon-based materials, including graphene, graphene oxide (GO), and carbon nanotubes, are popular SALDI substrates due to their high surface area, strong UV absorption, and chemical stability. Their enhancement mechanism is often attributed to efficient energy absorption and charge transfer rather than LSPR. Functionalization can further enhance their performance and selectivity. For example, boronic acid-functionalized 2D boron nanosheets (2DBs) and GO-VPBA have been developed for the selective enrichment and detection of cis-diol-containing compounds like sugars and nucleosides. The GO-VPBA matrix improved detection limits for guanosine by about 115-fold and 131-fold compared to conventional GO and the organic matrix DHB, respectively [12].

Hybrid and Functionalized Nanomaterials

Combining different materials into hybrid structures can create synergistic effects. A notable example is p-AAB/MXene, where p-aminoazobenzene (p-AAB), a molecule with excellent energy absorption capability, is used to modify multilayer Ti3C2TX (MXene) [15]. This modification significantly improves the laser absorption of the original material, making it an effective SALDI matrix. Furthermore, p-AAB/MXene also functions as a powerful adsorbent, enabling the enrichment of target pollutants like p-phenylenediamine-quinones (PPDQs) and diamide insecticides (DAIs) from beverages and PM2.5 before direct SALDI-TOF MS analysis, achieving limits of detection at the ng mL-1 level [15].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Selected SALDI Nanomaterials for Small Molecule Analysis

| Nanomaterial | Example Analytes | Limit of Detection (LOD) | Key Advantage | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gold Nanoshells (SiO2@Au NGS) | Amino acids, Sugars, Flavonoids | Low attomole range (e.g., 150 amol for GSH [12]) | Tunable plasmonic properties; high salt tolerance | Metabolic profiling [14] |

| Tuned AuNP Arrays | Stearic acid, Glutathione, Crystal violet | Not specified (high sensitivity demonstrated) | Adjustable nanogaps for optimized LSPR | Detection of sulfonamide in lake water [11] |

| Functionalized GO (GO-VPBA) | Adenosine, Guanosine, Galactose | Guanosine: 0.63 pmol mL⁻¹ | Selective enrichment via boronic acid chemistry | Analysis of nucleosides in urine [12] |

| p-AAB/MXene | PPDQs, DAIs (pesticides) | ng mL⁻¹ level | Dual function: adsorbent & matrix; rapid screening | Pollutants in beverages & PM2.5 [15] |

| Covalent Organic Frameworks (COFs) | PFOS, cis-Diol compounds | PFOS: 0.5 ng mL⁻¹ [12] | Large surface area; designable pores | Detection of PFOS in zebrafish tissues [12] |

Experimental Protocols: From Substrate Preparation to MS Analysis

This section provides detailed methodologies for key experiments cited in this review, enabling researchers to replicate and build upon these advanced SALDI techniques.

Protocol 1: Preparing Plasmonic AuNP Arrays with Tunable Gaps

This "bottom-up" method creates uniform gold nanoparticle substrates with controllable LSPR coupling [11].

- Substrate Functionalization: Begin with a clean, one-side-polished silicon wafer. Treat the wafer with oxygen plasma or a piranha solution (a mixture of concentrated sulfuric acid and hydrogen peroxide) to create a hydroxyl-rich surface. Then, vapor-deposit or immerse the wafer in a solution of 3-aminopropyltriethoxysilane (APTES) to form a positively charged amine-terminated monolayer.

- Gold Nanoparticle (AuNP) Synthesis: Synthesize negatively charged, citrate-capped AuNPs (e.g., ~15 nm diameter) using the standard Turkevich method (reducing chloroauric acid with sodium citrate).

- Gap Tuning via Ionic Strength: Adjust the LSPR-coupled gap between AuNPs by controlling the ionic strength of the AuNP solution. Add specific concentrations of sodium chloride (NaCl) to the AuNP solution to partially screen the electrostatic repulsion between particles.

- Electrostatic Assembly: Immerse the APTES-functionalized silicon substrate (positively charged) into the NaCl-mixed AuNP solution (negatively charged) for a set period (e.g., 2 hours). The AuNPs will electrostatically assemble onto the silicon surface.

- Washing and Drying: Gently rinse the assembled substrate with deionized water and dry under a stream of nitrogen gas. Characterization via scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and UV-Vis spectroscopy should confirm the uniformity and density of the AuNP array.

Protocol 2: Synthesizing Silica@Gold Nanogap Shells (SiO2@Au NGS)

This protocol yields core-shell nanostructures with abundant plasmonic hot spots [14].

- Silica Core Synthesis: Prepare monodisperse silica nanoparticles (e.g., ~100 nm) via the Stöber process. Mix tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS) with ethanol and catalyze with ammonium hydroxide at 60°C for 1 hour, then stir at 25°C for 19 hours. Wash the resulting silica NPs with ethanol via centrifugation.

- Surface Amination: Amino-functionalize the silica NPs by stirring with (3-aminopropyl)trimethoxysilane (APTS) and a catalytic amount of NH4OH for 12 hours. Wash several times with ethanol.

- Seed Immobilization: Mix the aminated silica NPs with a pre-synthesized colloidal solution of small AuNP seeds (e.g., ~2-3 nm, synthesized with tetrakis(hydroxymethyl)phosphonium chloride). Stir overnight to allow electrostatic attachment of Au seeds to the silica surface. Wash with water to remove excess seeds.

- Seed-Mediated Growth: To grow the gold nanoshell, disperse the seed-immobilized silica NPs in an aqueous polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) solution. Under constant stirring, simultaneously add specific volumes of a gold precursor (e.g., 50 mM HAuCl4) and a reducing agent (e.g., 100 mM ascorbic acid) at fixed time intervals. The final concentration of the gold precursor (e.g., 0.5 to 2.0 mM) controls the ultimate shell thickness and nanogap size.

- Purification: Wash the final SiO2@Au NGS product with deionized water and redisperse in ethanol for storage and further use.

General SALDI-TOF MS Analysis Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the standard procedure for analyzing samples using a prepared SALDI substrate.

Diagram 1: Standard SALDI-TOF MS Analysis Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of SALDI-MS relies on a suite of essential materials and reagents. The following table details key components for the featured experiments.

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for SALDI-MS Research

| Item | Function in SALDI-MS | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Silicon Wafer | Provides a flat, rigid substrate for nanomaterial assembly. | Base substrate for APTES functionalization and AuNP array assembly [11]. |

| APTES ((3-Aminopropyl)triethoxysilane) | Forms a positively charged monolayer on silicon for electrostatic nanoparticle binding. | Functionalizing silicon wafers to attract negatively charged AuNPs [11] [14]. |

| Chloroauric Acid (HAuCl₄) | Gold precursor for synthesizing gold nanoparticles and nanostructures. | Synthesis of AuNP seeds and growth of gold nanoshells on silica cores [14]. |

| Tetraethyl Orthosilicate (TEOS) | Precursor for synthesizing monodisperse silica nanoparticles (SiO₂). | Creating silica core nanoparticles via the Stöber process [14]. |

| Sodium Citrate / Ascorbic Acid | Reducing agents for synthesizing and growing metal nanoparticles. | Sodium citrate for AuNP synthesis; ascorbic acid for seed-mediated growth of gold shells [11] [14]. |

| Polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) | A stabilizing agent that controls nanoparticle growth and prevents aggregation. | Used during the gold shell growth process to stabilize the nanostructures [14]. |

| MXene (Ti₃C₂Tₓ) | A 2D material serving as a base substrate with high surface area and modifiability. | Used as a backbone for modification with p-AAB to create a dual-function adsorbent/matrix [15]. |

| p-Aminoazobenzene (p-AAB) | A chromophore with high laser energy absorption. | Modifying MXene to enhance its laser absorption capability for improved LDI efficiency [15]. |

| Covalent Organic Frameworks (COFs) | Porous polymers for selective enrichment of analytes based on size and chemistry. | Enriching perfluorooctanesulfonic acid (PFOS) from complex tissue samples prior to SALDI-MS [12]. |

Application in Pharmaceutical Research and Beyond

The unique advantages of SALDI-MS have led to its adoption in diverse fields, with pharmaceutical research being a primary beneficiary.

Drug Discovery and Development

SALDI-MS is revolutionizing early-stage drug discovery. Its label-free nature makes it ideal for high-throughput screening (HTS) of compound libraries against therapeutic targets like enzymes and receptors. Techniques like Self-Assembled Monolayer Desorption Ionization (SAMDI) use functionalized target plates to immobilize enzymes or other biomolecules. The activity of potential drug candidates can be assessed directly on the chip by monitoring substrate conversion or inhibitor binding via SALDI-MS, eliminating the need for fluorescent labels and reducing false positives [13]. Furthermore, SALDI-based mass spectrometry imaging (MSI) is invaluable in later stages, providing spatial-chemical information about drug distribution, metabolism, and potential toxicity within tissues, thereby offering a more complete picture of the drug's response [13].

Environmental and Food Safety Monitoring

The ability to detect trace-level small molecules in complex matrices makes SALDI-MS a powerful tool for environmental and food safety. The p-AAB/MXene platform, for instance, has been successfully applied to rapidly screen for emerging environmental pollutants, such as p-phenylenediamine-quinones (PPDQs) in beverages and diamide insecticides (DAIs) in PM2.5 particulates with LODs at the ng mL⁻¹ level [15]. Similarly, functionalized nanomaterials enable the sensitive and selective detection of pesticide residues, mycotoxins, and heavy metals in food products, facilitating on-site and rapid monitoring [12] [16].

Clinical Diagnostics and Biomarker Discovery

In the clinical realm, SALDI-MS is used for profiling small-molecule metabolites, lipids, and other biomarkers in biofluids like blood, urine, and plasma. The detection of glutathione (GSH) at attomole levels using AuNP/ZnO nanorod substrates highlights the technique's potential for monitoring redox status and oxidative stress, which are implicated in various diseases [12]. The high sensitivity and specificity afforded by advanced SALDI substrates open new avenues for non-invasive disease diagnosis and metabolic monitoring.

The SALDI revolution, powered by inorganic nanomaterials, has definitively overcome the critical limitation of MALDI-MS for small-molecule analysis. By eliminating matrix interference and leveraging nanomaterial-enhanced ionization mechanisms like LSPR, SALDI-MS now delivers the high sensitivity, reproducibility, and specificity required for modern analytical challenges. The rational design of nanostructures—from tuned AuNP arrays and gold nanoshells to functionalized 2D materials and hybrid composites—has been instrumental in this progress. The technique has already proven its immense value in pharmaceutical research, environmental monitoring, and clinical diagnostics. Looking forward, the integration of SALDI-MS with other technologies, such as microfluidics for automated sample handling and artificial intelligence for spectral data analysis and pattern recognition, will further streamline workflows and enhance analytical power [13] [17]. The continued development of multifunctional "lab-on-a-chip" SALDI platforms that combine enrichment, separation, and detection promises to make high-sensitivity, high-throughput small-molecule analysis more accessible and routine than ever before.

The integration of two-dimensional (2D) materials into mass spectrometry represents a paradigm shift in small molecule analysis. This whitepaper details how the unique properties of 2D materials—specifically, their widely tunable bandgaps and exceptionally high surface areas—directly address critical challenges in ionization efficiency. These materials, including graphene, black phosphorus (BP), and transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDs), mitigate matrix interference and enhance sensitivity by leveraging their tunable optoelectronic properties and substantial surface-to-volume ratios. Framed within the context of ionization efficiency for small molecule research, this document provides a technical guide on the fundamental principles, experimental protocols, and future directions of 2D material-assisted laser desorption/ionization mass spectrometry (LDI-MS), serving as a resource for researchers and drug development professionals.

The advent of two-dimensional (2D) materials has dramatically transformed the landscape of modern electronics and sensing technologies [18] [19]. These materials, characterized by their atomically thin layers and strong in-plane covalent bonds, possess a suite of exceptional physical and chemical properties. For researchers focused on small molecule analysis, such as metabolites and pharmaceuticals, two properties are particularly transformative: bandgap tunability and high surface-to-volume ratio [20] [21]. These properties make 2D materials ideal for improving ionization efficiency in techniques like matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization mass spectrometry (MALDI-MS).

Traditional organic matrices used in MALDI-MS, such as α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid (CHCA), often generate significant background signals in the low-mass region (<1000 Da), severely limiting their utility for small molecule detection [20]. The exploration of 2D materials as alternative matrices has emerged as a powerful solution to these challenges. Their large surface area enables efficient analyte adsorption, while their tunable electronic band structures allow for optimized energy absorption and charge transfer upon laser irradiation [20] [21]. This article provides an in-depth examination of these core properties, their role in enhancing ionization efficiency, and detailed methodologies for their application in analytical research.

Core Property 1: Bandgap Tunability

Fundamentals and Mechanisms

The bandgap, a fundamental semiconductor property, is the energy difference between the valence and conduction bands. It critically determines a material's optical absorption and electronic behavior. Unlike conventional semiconductors with fixed bandgaps, 2D materials exhibit highly tunable bandgaps, achievable through several sophisticated methods [22]:

- Number of Layers: Quantum confinement effects cause the bandgap to vary with material thickness. For instance, black phosphorus (BP) transitions from a bulk bandgap of 0.3 eV to a monolayer bandgap of ~2.0 eV [20] [22]. Similarly, semiconducting TMDs like MoS₂ show significant bandgap changes from bulk to single-layer forms [22].

- External Electric Fields: The application of an electric field can induce strong bandgap modifications via the Stark effect, with tunability an order of magnitude greater than in bulk materials [22].

- Strain Engineering: Applying tensile or compressive biaxial strain can continuously reduce or increase the bandgap of materials like MoS₂ and WS₂ [22].

- Alloying and Heterostructuring: Creating heterostructures by stacking different 2D materials or forming ternary alloys (e.g., Mo₁₋ₓWₓS₂) allows for precise bandgap engineering and the creation of tailored electronic band alignments [18] [22].

Impact on Ionization Efficiency

In LDI-MS, the matrix must efficiently absorb laser energy and transfer it to the analyte. A material with a bandgap that aligns well with the laser photon energy enables superior energy absorption and charge transfer, directly boosting ionization efficiency [20].

Black phosphorus serves as a premier example. Its bandgap can be tuned across a wide range (0.3 eV to 2.0 eV), which corresponds to an optical absorption spectrum that spans from the terahertz to the visible region [20] [22]. This broad tunability allows BP to be optimized for use with different laser wavelengths, maximizing energy absorption and facilitating efficient analyte desorption and ionization [20]. The linearly polarized light emission from monolayer and few-layer BP further enhances its potential for controlled energy transfer [20].

Table 1: Bandgap Tunability in Select 2D Materials and Implications for Ionization

| Material | Tuning Mechanism | Bandgap Range | Relevance to Ionization Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|

| Black Phosphorus (BP) | Layer Number | 0.3 eV (bulk) to 2.0 eV (monolayer) [20] [22] | Enables optimization for a wide range of laser photon energies. |

| Transition Metal Dichalcogenides (TMDs) | Layer Number, Alloying | 1.0 eV to 2.0 eV (e.g., MoS₂, WS₂) [22] | Provides semiconducting properties suitable for UV laser absorption. |

| Graphene Derivatives | Chemical Doping, Functionalization | Near 0 eV to ~4.0 eV [23] | Functionalization can open a bandgap, tailoring charge transfer capabilities. |

Diagram 1: Pathways from bandgap tuning to ionization efficiency.

Core Property 2: High Surface Area

Quantifying the Surface Area

Two-dimensional materials possess an intrinsically high specific surface area because their entire structure is exposed to the environment. For example, black phosphorus has a reported specific surface area greater than 2630 m²/g [20], while graphene's theoretical value reaches 2630 m²/g [21]. This exceptional surface area is a direct consequence of their atomically thin, sheet-like morphology.

This property is crucial for sensor applications, as it allows for extensive interaction with target analytes [19]. In the context of ionization, a high surface area provides a vast platform for the adsorption of small molecule analytes. The wrinkled, nearly transparent flake-like structure of graphene and other 2D materials, as visualized via transmission electron microscopy, further enhances this adsorptive capacity [21].

Role in Analyte Adsorption and Ionization

The high surface area of 2D materials directly enhances ionization efficiency in two key ways:

- Increased Analyte Loading: The large surface allows a greater number of analyte molecules to be immobilized in close proximity to the matrix, increasing the number of molecules available for ionization per unit area [20] [21].

- Efficient Energy Transfer: When a laser irradiates the 2D matrix, the energy is absorbed by the material and rapidly transferred to the adsorbed analyte molecules. The short diffusion distance and intimate contact between the matrix and analytes facilitate efficient desorption and ionization, minimizing analyte fragmentation [21].

The combination of these factors means that 2D materials can act as superior energy receptors. The graphene matrix, for instance, functions as a substrate to trap analytes and transfer energy upon laser irradiation, allowing analytes to be readily desorbed/ionized while eliminating the interference of intrinsic matrix ions that plague conventional organic matrices [21].

Experimental Protocols: 2D Materials in LDI-MS

This section outlines detailed methodologies for employing 2D materials as matrices in LDI-MS, focusing on graphene and black phosphorus.

Graphene Matrix Preparation and Analysis

The following protocol is adapted from the pioneering work using graphene as a MALDI matrix [21].

Materials:

- Graphene (prepared from chemical reduction of graphene oxide)

- Trifluoroacetic acid (TFA), α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid (CHCA) - for comparison

- Analytes: Amino acids (Glutamic acid, Histidine, Tryptophan), polyamines, anticancer drugs, nucleosides, steroids (Cholesterol, Squalene)

- Ethanol, acetonitrile (HPLC grade)

Matrix Preparation:

- Disperse 1 mg of graphene in 1 mL of ethanol.

- Sonicate the suspension for 3 minutes to achieve a homogeneous dispersion.

- Pipette 1 µL of the graphene suspension onto the MALDI sample target.

- Allow it to air-dry at room temperature for 5-10 minutes to form a thin, uniform matrix layer.

Sample Preparation:

- Prepare analyte stock solutions (e.g., 10 mM) in water or ethanol, depending on solubility.

- Pipette 0.5 µL of the analyte solution onto the pre-formed graphene matrix layer.

- Allow the sample spot to air-dry for 5-10 minutes before loading into the mass spectrometer.

Solid-Phase Extraction (SPE) Coupled with MALDI-MS:

- Rinse 2 mg of graphene with acetonitrile and water.

- Suspend the graphene in 0.3 mL of 50% (vol/vol) methanol and sonicate for 3 minutes.

- Pipette 10 µL of the graphene suspension into 100 µL of a dilute analyte solution.

- Sonicate the mixture for 10 minutes to promote analyte adsorption.

- Centrifuge at 13,000 rpm for 10 minutes and remove the supernatant.

- Resuspend the analyte-enriched graphene pellet in 5 µL of methanol/water (1:1, v/v).

- Pipette ~1 µL of the final suspension onto the sample target for MALDI-TOF MS analysis.

Mass Spectrometry Acquisition:

- Instrument: MALDI-TOF mass spectrometer (e.g., Voyager DE STR).

- Ion Mode: Positive reflection mode.

- Laser: N₂ laser (337 nm).

- Acquisition Parameters: Acceleration voltage at 20 kV; delayed extraction time of 190 ns.

- Spectrum: Acquire as an average of 100 laser shots.

Black Phosphorus (BP) Matrix Preparation and Analysis

BP's unique properties make it a highly effective LDI matrix, particularly for small molecules [20].

Materials:

- Bulk BP crystals or BP nanomaterials (e.g., BP Quantum Dots).

- Analytes: Metabolites, pharmaceuticals, glucose, etc.

- Solvents: Ethanol, water, isopropanol.

Synthesis of BP Nanomaterials (Top-Down Exfoliation):

- Ultrasonic Liquid-Phase Exfoliation: Place bulk BP crystals in an appropriate solvent (e.g., N-cyclohexyl-2-pyrrolidone). Sonicate the mixture using a probe ultrasonicator for several hours under an inert atmosphere to prevent oxidation. Centrifuge to remove unexfoliated bulk material and collect the supernatant containing BP nanosheets or quantum dots [20].

- Solvothermal Treatment: A method that combines high temperature and pressure to exfoliate bulk BP into quantum dots [20].

- High-Energy Ball Milling: Use mechanical force to grind bulk BP into smaller quantum dots [20].

Matrix and Sample Preparation:

- Prepare a suspension of BP nanomaterials (e.g., 1 mg/mL) in a solvent like ethanol or isopropanol with brief sonication.

- Deposit 1-2 µL of the BP suspension onto the MS target and allow to dry.

- Spot 0.5-1 µL of the analyte solution onto the BP layer and let it co-crystallize/dry.

MS Analysis and Mechanism:

- The analysis follows a similar setup to the graphene protocol (LDI-TOF MS).

- The ionization mechanism in BP-assisted LDI-MS (BALDI-MS) is proposed to be similar to other surface-assisted LDI (SALDI) processes. The BP substrate absorbs laser energy, inducing rapid heating that leads to the desorption and ionization of the adsorbed analytes. BP's high carrier mobility (predicted between 1000 and 26,000 cm² V⁻¹ s⁻¹) facilitates efficient charge transfer, which is critical for ionization [20].

Diagram 2: Experimental workflow for 2D matrix preparation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials and Reagents for 2D Material-Assisted LDI-MS

| Item Name | Function/Brief Explanation | Example Context |

|---|---|---|

| Graphene Matrix | Traps analytes and transfers laser energy efficiently; eliminates matrix ion interference in low-mass region [21]. | Analysis of amino acids, polyamines, steroids [21]. |

| Black Phosphorus (BP) Matrix | Offers thickness-dependent bandgap for tunable light absorption; high carrier mobility enhances charge transfer [20]. | Detection of endogenous aldehydes, pharmaceuticals, and metabolites [20]. |

| BP Quantum Dots (BPQDs) | Zero-dimensional BP with high surface-area-to-volume ratio; useful for fluorescence sensing and optoelectronic applications [20]. | Potentially used as a highly sensitive matrix for small molecule ionization. |

| Transition Metal Dichalcogenide (TMD) MX₂ | Semiconducting properties (e.g., MoS₂, WS₂) with bandgaps in visible range; suitable for UV laser absorption [18] [19]. | Emerging as alternative matrices; also used in photovoltaic and sensing applications [23]. |

| MXenes (Mn₊₁XₙTₓ) | Metallic conductivity and hydrophilic nature; large specific surface area enhances sensing capabilities [19]. | Used in composites for flexible sensor technology; potential for LDI-MS. |

| Ultrasonic Liquid-Phase Exfoliation | A top-down approach to produce high-quality nanosheets and quantum dots from bulk crystals [20]. | Standard synthesis method for BPQDs and other 2D nanomaterials for matrix use. |

The unique properties of 2D materials, namely their tunable bandgaps and high specific surface areas, provide a powerful foundation for enhancing ionization efficiency in the analysis of small molecules. These materials directly address the limitations of conventional MALDI matrices by reducing background interference, improving reproducibility, and increasing salt tolerance [20] [21].

Future research will focus on bridging the gap between laboratory proof-of-concept and high-volume manufacturing. Key challenges include improving the scalable synthesis of defect-free 2D films and understanding long-term interface stability [23] [24]. Emerging trends, such as the use of machine learning to optimize synthesis parameters and predictive modeling of material properties, will be crucial [25]. Furthermore, developing multifunctional heterostructures that combine defect passivation, moisture blocking, and graded band alignment in a single stack holds immense promise [23]. As metrology and standardization efforts by organizations like the International Roadmap for Devices and Systems (IRDS) advance, the broader adoption of 2D materials in next-generation analytical platforms for drug development and clinical diagnostics is assured [24].

In mass spectrometry (MS), the ionization process serves as the critical first step, converting neutral molecules into gas-phase ions that can be separated and detected based on their mass-to-charge ratio. The selection of an appropriate ionization technique directly determines the success of an experiment, impacting sensitivity, reproducibility, and the quality of the resulting data [26]. For researchers focused on small molecule analysis, particularly in drug development, understanding the comparative mechanisms, advantages, and limitations of the major ionization techniques is essential for methodological design.

This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of three fundamental ionization approaches: Electrospray Ionization (ESI), Atmospheric Pressure Chemical Ionization (APCI), and Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization (MALDI), including its derivative Surface-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization (SALDI). The operational principles of each technique will be explored alongside practical guidance for their application in small molecule research, with a specific emphasis on ionization efficiency within the context of analytical method development.

Core Principles and Mechanisms

Electrospray Ionization (ESI)

Electrospray Ionization is a soft ionization technique that operates at atmospheric pressure and is exceptionally well-suited for the analysis of polar molecules and large biomolecules. In the ESI process, a sample solution is sprayed through a charged capillary needle to which a high voltage (typically several kilovolts) is applied, creating a fine mist of charged droplets. As the solvent evaporates, Coulombic repulsion forces within the shrinking droplets overcome surface tension, leading to droplet fission and ultimately the release of gas-phase analyte ions [27]. A key characteristic of ESI is its tendency to produce multiply charged ions for species containing multiple protonation sites, such as proteins and peptides. This charge multiplicity effectively reduces the mass-to-charge ratio ((m/z)), enabling the analysis of high molecular weight compounds on instruments with limited (m/z) ranges [27] [28].

The primary strength of ESI lies in its compatibility with liquid chromatography (LC-MS), making it the cornerstone technique for the analysis of complex mixtures in proteomics, metabolomics, and pharmaceutical applications [27]. However, ESI is highly susceptible to ion suppression effects, where the presence of co-eluting compounds (such as salts, buffers, or other analytes) can interfere with the efficient ionization of the target molecule, thereby reducing sensitivity [26] [27]. This technique generally requires samples to be in solution and is less effective for analyzing non-polar compounds.

Atmospheric Pressure Chemical Ionization (APCI)

Atmospheric Pressure Chemical Ionization represents a gas-phase ionization technique that shares operational similarities with ESI but employs a fundamentally different ionization mechanism. In APCI, the sample solution is first nebulized and vaporized in a heated chamber (typically at temperatures of 350-500°C) to create a gaseous aerosol. Subsequently, a corona discharge needle creates a plasma of solvent reagent ions. These reagent ions then undergo gas-phase chemical reactions with the vaporized analyte molecules, most commonly through proton transfer (producing [M+H]⁺ or [M-H]⁻ ions) or charge exchange reactions [26] [27].

APCI demonstrates particular efficacy for the analysis of less polar, semi-volatile, and thermally stable small molecules that ionize poorly by ESI [26] [27]. It generally exhibits greater tolerance to higher buffer concentrations compared to ESI and is less prone to ion suppression effects from matrix components. However, the requirement for thermal vaporization renders APCI unsuitable for the analysis of large, thermally labile biomolecules such as proteins, which may decompose under the applied heat [27].

MALDI and SALDI

Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization operates on a different principle from the aforementioned techniques. In MALDI, the analyte is co-crystallized with a large molar excess of a small, UV-absorbing organic matrix compound (e.g., 2,5-dihydroxybenzoic acid). When irradiated with a pulsed laser (typically a nitrogen laser at 337 nm), the matrix efficiently absorbs the laser energy, leading to rapid thermal heating and desorption of both the matrix and analyte. The analyte is then ionized through proton transfer reactions in the expanding plume of desorbed material [27] [28]. MALDI typically generates predominantly singly charged ions, simplifying spectral interpretation, especially for complex mixtures [28]. Its strengths include high sensitivity, rapid analysis speed, compatibility with solid samples, and minimal sample consumption.

Surface-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization represents a matrix-free evolution of MALDI that addresses its key limitation for small molecule analysis: spectral interference from low-mass matrix ions. SALDI utilizes nanostructured metallic surfaces or inorganic nanoparticles (e.g., gold, silver, or silicon) to assist in the laser desorption/ionization process [29] [14]. These nanomaterials absorb laser energy and facilitate charge transfer to the analyte without producing the interfering chemical noise associated with organic matrices. This makes SALDI particularly valuable for analyzing small molecules (typically < 1000 Da), as it provides clean, interpretable spectra in the low-mass region [29].

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Ionization Techniques

| Feature | ESI | APCI | MALDI | SALDI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ionization Phase | Liquid solution/Liquid-gas interface | Gas phase | Solid phase | Solid phase |

| Primary Mechanism | Charged droplet evaporation/charge residue | Chemical ionization via reagent ions | Proton transfer in desorbed plume | Energy/charge transfer from nanostructures |

| Typical Charge States | Multiple charges common | Single charge dominant | Single charge dominant | Single charge dominant |

| Sample Introduction | Liquid flow | Liquid flow or vaporized | Solid-state co-crystal | Solid-state mixture with nanoparticles |

| Energy Source | High electric field | Heat + Corona discharge | Pulsed UV Laser | Pulsed UV Laser |

Comparative Performance and Analytical Figures of Merit

The selection of an ionization technique for a specific analytical challenge requires a clear understanding of their respective performance characteristics. The following section provides a comparative analysis based on key analytical figures of merit.

Table 2: Comparative Performance for Small Molecule Analysis

| Characteristic | ESI | APCI | MALDI | SALDI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ionization Efficiency for Polar Molecules | Excellent | Good | Good | Good |

| Ionization Efficiency for Non-Polar Molecules | Poor | Excellent | Moderate | Moderate |

| Mass Range | High (due to multiple charging) | Medium (for small molecules) | Very High | Very High |

| Susceptibility to Matrix Effects | High | Moderate | Low (but matrix interference present) | Very Low |

| Tolerance to Salts/Buffers | Low | Moderate | Low (conventional) | High |

| Analytical Reproducibility | Good | Good | Moderate to Poor | Good (with optimized substrates) |

| Quantitative Capability | Strong | Strong | Challenging (historically) | Promising |

| Throughput Potential | Good (tied to LC) | Good (tied to LC) | Very High | Very High |

| Compatibility with LC-MS | Excellent | Excellent | Limited | Limited |

The data in Table 2 highlights the complementary nature of these techniques. ESI excels for polar analytes and is the workhorse for LC-MS-based quantitative analysis, though it suffers from high susceptibility to ion suppression in complex matrices [26] [27]. APCI effectively bridges the gap for less polar, thermally stable small molecules and offers more robust performance with samples containing higher buffer concentrations [27].

While MALDI offers high throughput and sensitivity, its traditional drawbacks for small molecule analysis include poor reproducibility due to heterogeneous crystal formation and severe spectral interference from the organic matrix in the low-mass region [29] [30]. SALDI directly addresses the interference issue. For instance, using gold nanoshells with nanogap-rich structures (SiO₂@Au NGS) as a SALDI substrate has demonstrated efficient detection of amino acids, sugars, and flavonoids with high sensitivity, reproducibility, and salt tolerance [29] [14]. This positions SALDI as a powerful alternative for direct small molecule analysis where a clean background in the low-mass range is critical.

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

ESI Method for Small Molecule Analysis

A typical ESI-MS protocol for small molecules involves the following steps:

- Sample Preparation: Dissolve the target analyte in a volatile solvent compatible with MS, such as methanol, acetonitrile, or water, often with a modifier (0.1% formic acid or ammonium acetate) to promote ionization. The final concentration should be in a suitable range (e.g., pM to µM) for the instrument's sensitivity.

- Instrument Setup: Connect the LC system to the mass spectrometer. Set the ESI source parameters, which typically include:

- Capillary Voltage: 2.5 - 4.0 kV (positive mode) or 2.0 - 3.5 kV (negative mode).

- Source Temperature: 100 - 150°C.

- Desolvation Gas (N₂) Flow: 300 - 800 L/hour.

- Cone Voltage: 10 - 50 V (optimized for the analyte to balance sensitivity and fragmentation).

- Data Acquisition: Introduce the sample via direct infusion or, preferably, LC separation. For LC-ESI-MS, a flow rate of 0.1 - 0.5 mL/min is common. Acquire data in full-scan or selected ion monitoring (SIM) mode for quantification.

SALDI Protocol Using Gold Nanoshells with Nanogaps

The following detailed protocol is adapted from recent research on using SiO₂@Au NGS for small molecule analysis [29] [14]:

- Synthesis of SiO₂@Au NGS:

- Silica Core Synthesis: Prepare silica nanoparticles (NPs) via the Stöber process. Mix tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS, 1.6 mL) with ethanol (40 mL), then add an ammonium hydroxide solution (3-5.5 mL) as a catalyst. Stir vigorously for 1 hour at 60°C, then continue for 19 hours at 25°C. Wash the resulting silica NPs several times with ethanol via centrifugation.

- Surface Amination: Modify the silica NP surface with amino groups by stirring with (3-aminopropyl) trimethoxysilane (APTS, 15.5 μL) and NH₄OH (10 μL) for 12 hours. Wash with ethanol.

- Gold Seed Immobilization: Mix the aminated silica NPs (2 mg) with a colloidal solution of small gold nanoparticle seeds (10 mL) and allow to incubate overnight. Wash with deionized water.

- Gold Shell Growth: Disperse the seed-immobilized silica NPs (SiO₂@Au, 10 mg) in an aqueous polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) solution. Under constant stirring, simultaneously add aliquots of a 50 mM gold(III) chloride solution and a 100 mM ascorbic acid solution at 5-minute intervals. Repeat the additions to achieve the desired final Au³⁺ concentration (e.g., 0.5 to 2.0 mM) to control the gold shell thickness. The optimal shell thickness was found to be approximately 17.2 nm for maximum absorbance and SALDI efficiency [14].

- Sample Preparation for SALDI-MS:

- Prepare stock solutions of small molecule analytes (e.g., amino acids, sugars, pharmaceuticals) at a concentration of 100 µM in a suitable solvent like water or acetonitrile.

- Mix the SiO₂@Au NGS suspension with the analyte solution at a defined ratio (e.g., 1:1 v/v).

- Spot 1-2 µL of the mixture onto a standard MALDI target plate and allow it to dry at room temperature, forming a homogeneous layer.

- SALDI-TOF MS Data Acquisition:

- Load the target plate into the mass spectrometer vacuum chamber.

- Set the laser energy to a threshold level that provides sufficient signal intensity with minimal fragmentation (soft ionization). This is typically slightly above the ablation threshold.

- Acquire mass spectra in reflection positive or negative ion mode, accumulating signals from 50-200 laser shots per spot.

- Calibrate the mass axis using a standard calibrant appropriate for the mass range of interest.

SALDI Workflow with Nanoshells

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

The successful implementation of the ionization techniques discussed relies on a suite of specialized reagents and materials.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Item | Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| ESI:Electrospray Capillaries (Fused Silica) | Conduit for applying high voltage and generating charged droplets. | All ESI-MS applications. |

| ESI/APCI:Volatile Buffers & Modifiers (e.g., Formic Acid, Ammonium Acetate) | Adjust pH and promote protonation/deprotonation of analytes in solution. | Enhancing ionization efficiency in LC-ESI/APCI-MS. |

| MALDI:Organic Matrices (e.g., DHB, CHCA, SA) | Absorb laser energy and facilitate soft desorption/ionization of the analyte. | Protein, peptide, and polymer analysis by MALDI-TOF. |

| SALDI:Gold Nanoshells (SiO₂@Au NGS) | Nanostructured substrate for laser energy absorption; eliminates matrix interference. | Sensitive analysis of small molecules (e.g., amino acids, drugs). |

| SALDI/MALDI:MALDI Target Plates (Stainless Steel, ITO-coated glass) | Sample presentation platform for laser irradiation under vacuum. | All MALDI and SALDI experiments; ITO-coated plates are for imaging. |

| APCI:Corona Discharge Needles | Generates a stable plasma for the creation of reagent ions. | All APCI-MS applications. |

| General:High-Purity Solvents (MS-grade) | Dissolve and introduce samples with minimal background contamination. | Sample preparation for ESI, APCI, and matrix/sample solutions for MALDI/SALDI. |

The selection of an ionization technique for small molecule analysis is not a one-size-fits-all decision but a strategic choice based on the physicochemical properties of the analyte, the complexity of the sample matrix, and the specific analytical objectives. ESI remains the dominant technique for polar molecules and liquid chromatography-coupled workflows, while APCI provides a robust alternative for less polar and semi-volatile compounds. MALDI offers unparalleled speed and simplicity for solid samples and high-throughput applications.

However, for the analysis of small molecules where sensitivity and a clean spectral background are paramount, SALDI using advanced nanomaterials like gold nanoshells with nanogaps presents a powerful and increasingly reliable option. By overcoming the traditional limitations of MALDI related to matrix interference, SALDI opens new avenues for efficient, reproducible, and sensitive detection of low molecular weight compounds in drug development and related research fields. The ongoing development of novel substrates and the refinement of methodologies promise to further establish SALDI's role in the mass spectrometry toolkit.

Advanced Materials and Workflows: Boosting Sensitivity in Real-World Applications

Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization Mass Spectrometry (MALDI-MS) has emerged as a powerful tool for the rapid, sensitive, and high-throughput analysis of diverse analytes in drug development and clinical research [20]. However, when applied to the detection of low molecular weight substances (<1000 Da)—such as metabolites, pharmaceuticals, and endogenous compounds—conventional organic matrices reveal significant limitations [20]. Traditional UV-absorbing organic matrices like α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid (CHCA) and sinapinic acid (SA) generate substantial background interference in the low-mass region due to matrix-related adducts and fragments, effectively suppressing the target analyte signals [20]. This fundamental constraint has prompted the exploration of novel matrix materials capable of minimizing such interference while maintaining high ionization efficiency.

Advanced photo-responsive and thermally stable nanomaterials offer a promising solution to challenges such as low-mass ion suppression and the "sweet spot" effect prevalent in conventional MALDI-MS [20]. Within this landscape, black phosphorus (BP) has emerged as a particularly promising next-generation matrix, first demonstrated by He et al. for detecting endogenous aldehydes by leveraging BP's unique optoelectronic and physicochemical properties [20] [31]. This technical guide examines the fundamental properties, synthesis methodologies, and experimental applications of BP matrices, contextualized within the broader research objective of enhancing ionization efficiency for small molecule analysis.

Fundamental Properties of Black Phosphorus as an Ideal LDI Matrix

An ideal LDI matrix requires efficient energy absorption, high chemical and thermal stability, and effective charge transfer capabilities to facilitate analyte desorption and ionization [20]. Black phosphorus possesses several intrinsic properties that render it exceptionally suitable for this application.

Structural and Electronic Characteristics

Black phosphorus exhibits a puckered honeycomb lattice structure in an orthorhombic crystalline arrangement (space group Cmca) [20]. This structure is characterized by atomic distances of 3.6 Å and 3.8 Å between the nearest and next-nearest layers, respectively [20]. A critical property for its function as a matrix is its thickness-dependent bandgap, which tunably ranges from approximately 0.3 eV for bulk material to 2.0 eV for a monolayer [20]. This wide, tunable bandgap allows for optimal light absorption across various laser wavelengths used in LDI-MS systems.

The electronic properties of BP are equally remarkable, featuring high carrier mobility predicted between 1000 and 26,000 cm² V⁻¹ s⁻¹ [20]. This exceptional charge transport capability facilitates efficient energy and charge transfer during the laser desorption/ionization process, directly enhancing ionization efficiency for target analytes.

Comparative Physicochemical Properties

The table below summarizes key properties of BP that contribute to its performance as an LDI matrix, compared to other 2D materials.

Table 1: Key Properties of Black Phosphorus Relevant to LDI-MS Performance

| Property | Value/Range | Significance for LDI-MS |

|---|---|---|

| Bandgap | 0.3 - 2.0 eV (tunable with thickness) | Enables broad laser wavelength absorption and efficient energy transfer [20] |

| Carrier Mobility | 1,000 - 26,000 cm² V⁻¹ s⁻¹ | Facilitates rapid charge transfer, enhancing analyte ionization [20] |

| Specific Surface Area | >2630 m²/g | Provides abundant surface for analyte adsorption and interaction [20] |

| Thermal Stability | 400 - 550 °C | Withstands localized laser heating without decomposition [20] |

| Light Transmittance | 79.9 - 81.2 % | Optimizes laser energy utilization [20] |

Synthesis and Functionalization of Black Phosphorus Matrices

The synthesis of BP for LDI-MS applications primarily follows top-down and bottom-up approaches, with recent advances emphasizing green chemistry principles and enhanced functionality.

Top-Down Synthesis Approaches

Top-down methods begin with bulk BP and exfoliate it into thinner layers or nanostructures. Liquid-phase exfoliation is a common technique that disperses bulk BP in appropriate solvents via sonication or shear forces to produce few-layer nanosheets or quantum dots [32]. This method can yield BP quantum dots (BPQDs) with dimensions typically under 10 nm, which have demonstrated excellent performance in LDI-MS due to their high surface-area-to-volume ratio and edge-rich structure [20].

Mechanochemical synthesis has emerged as a particularly promising green alternative. This solvent-free approach utilizes high-energy planetary ball milling to directly transform red phosphorus into BP nanoparticles under an inert atmosphere [33]. The process can achieve gram-scale yields of high-quality BP within hours, characterized by pronounced B₂g and A₂g vibrational peaks at 435 cm⁻¹ and 463 cm⁻¹, respectively, in Raman spectroscopy, confirming successful allotropic conversion [33].

Diagram 1: Mechanochemical BP Synthesis

Bottom-Up and Hybrid Approaches

Bottom-up techniques construct BP nanostructures from atomic or molecular precursors. Solvothermal treatment represents one such method, producing BPQDs through high-temperature and high-pressure reactions in sealed vessels [20]. Chemical vapor transport (CVT) represents another traditional approach for growing high-quality BP crystals, though it involves high temperatures, extended reaction times (over 18 hours), and often utilizes heavy-metal iodides, making it less suitable for scalable production [33].

Recent innovations focus on hybrid nanomaterial creation. For instance, BP can be functionalized with polymers like polyglycerol (PG) to create BP-PG nanohybrids that offer enhanced stability and functionality [33]. This "grafting-from" polymerization approach can be integrated into mechanochemical synthesis, producing hydrophilic hybrids that maintain BP's reducing capabilities while improving dispersibility in aqueous solutions [33].

Experimental Protocols for BP-Assisted LDI-MS

BP Matrix Preparation for Small Molecule Analysis

Protocol 1: BP-Nanomaterial Matrix for Biofluid Analysis [31]

- BP Synthesis: Prepare BP nanosheets or quantum dots through liquid-phase exfoliation of bulk BP in appropriate solvents (e.g., N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone) via probe sonication followed by centrifugation to isolate the desired size fraction.