Mimetic Analogs for Bioinorganic Sorbent Preparation: From Laccase-like MOFs to Clinical Applications

This article explores the cutting-edge field of mimetic analogs for developing advanced bioinorganic sorbents, focusing on their foundational principles, synthesis methodologies, and transformative applications in biomedical research and drug development.

Mimetic Analogs for Bioinorganic Sorbent Preparation: From Laccase-like MOFs to Clinical Applications

Abstract

This article explores the cutting-edge field of mimetic analogs for developing advanced bioinorganic sorbents, focusing on their foundational principles, synthesis methodologies, and transformative applications in biomedical research and drug development. We provide a comprehensive examination of key materials including metal-organic frameworks (MOFs), laccase-mimetic polyoxometalates (POMs), and green-synthesized nanoparticles, detailing their unique sorption mechanisms and performance characteristics. The content addresses critical optimization strategies for enhancing stability and selectivity while presenting rigorous validation frameworks against conventional materials. Designed for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes current advancements and future trajectories for these innovative materials in clinical sample preparation, biomarker isolation, and therapeutic agent development.

Bioinorganic Mimetics Unveiled: Principles and Material Foundations

Defining Bioinorganic Sorbents and Their Mimetic Analogs

Bioinorganic sorbents represent a class of advanced materials that combine biological molecules with inorganic supports to create systems with specific recognition and high binding affinity for target analytes. These hybrid materials are engineered to address complex separation and sensing challenges, particularly in the presence of interfering compounds found in real-world samples such as biological fluids, food products, and environmental samples [1]. The core innovation in these systems lies in their molecular imprinting capability, where a template molecule shapes complementary binding cavities within a polymeric or protein-based matrix, resulting in remarkable molecular recognition properties [1].

Mimetic analogs, also referred to as biomimetic analogs, are synthetic or natural compounds that structurally or functionally resemble a target molecule of interest. These analogs serve as safer substitutes for hazardous, expensive, or unstable compounds during the development and optimization of bioinorganic sorbents [1]. For instance, in mycotoxin detection, mimetic analogs of zearalenone (such as coumarin and its derivatives) can be employed during the imprinting process to create specific binding sites without handling the toxic parent compound. The strategic use of these analogs enables researchers to pre-evaluate substitution possibilities and optimize template molecule concentrations through computational chemistry methods like molecular docking and molecular dynamics before proceeding with full sorbent development [1].

Key Applications and Performance Data

Bioinorganic sorbents modified with imprinted proteins demonstrate versatile application across environmental monitoring, food safety, and pharmaceutical development. Their capability for specific molecular recognition makes them particularly valuable for extracting target compounds from complex matrices.

Table 1: Sorption Capacity of Bioinorganic Sorbents for Various Target Molecules

| Target Compound | Sorbent Type | Matrix | Sorption Capacity (Q) | Imprinting Factor (IF) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zearalenone | SiO₂ with imprinted protein | Wheat extract | 4.79 mg/g | 2.45 |

| Coumarin | SiO₂ with imprinted protein | Model solution | 2.0 mg/g | - |

| 5,7-Dimethoxycoumarin | SiO₂ with imprinted protein | Model solution | 2.2 mg/g | - |

| 4-Hydroxycoumarin | SiO₂ with imprinted protein | Model solution | 1.2 mg/g | - |

| Quercetin | SiO₂ with imprinted protein | Model solution | 0.8 mg/g | - |

| Pb(II) ions | Porphyrin-silica hybrid | Water | 187.36 mg/g | - |

| Cu(II) ions | Porphyrin-silica hybrid | Water | 125.16 mg/g | - |

| Cd(II) ions | Porphyrin-silica hybrid | Water | 82.44 mg/g | - |

| Zn(II) ions | Porphyrin-silica hybrid | Water | 56.23 mg/g | - |

The data reveals that bioinorganic sorbents exhibit significant variability in binding capacity depending on the target molecule, with the highest affinity observed for zearalenone in wheat extract [1]. The imprinting factor of 2.45 indicates that the molecularly imprinted sorbent possesses more than twice the binding capacity compared to non-imprinted control materials, demonstrating the effectiveness of the imprinting process. For metal ion removal, porphyrin-based sorbents show a distinct selectivity pattern (Pb>Cu>Cd>Zn) attributable to differences in metal ion size and the energy requirements for incorporation into the porphyrin macrocyclic cavity [2].

Beyond the specific compounds listed, the application spectrum of advanced sorbents continues to expand. Hydrogel-based sorbents effectively extract analytes from complex matrices like biological samples by excluding high-molecular-weight compounds through their cross-linked polymeric networks while permitting small analyte molecules to enter their cavities [3]. Similarly, metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) have gained prominence as sorbents in sample preparation techniques due to their high specific surface area, tunable pore size, and extensive modification possibilities [4].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Preparation of Bioinorganic Sorbent Modified with Imprinted Proteins

This protocol details the synthesis of a specific bioinorganic sorbent based on silicon dioxide particles modified with imprinted bovine serum albumin (BSA) using mimetic analogs of zearalenone [1].

Materials and Equipment

- Inorganic support: Silicon dioxide (SiO₂) particles

- Template protein: Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA)

- Mimetic analogs: Coumarin, 4-hydroxycoumarin, quercetin, 5,7-dimethoxycoumarin

- Cross-linking agent: Glutaraldehyde

- Buffers: Phosphate buffer saline (PBS), acetate buffer

- Equipment: Orbital shaker, centrifuge, vacuum filtration system, spectrophotometer

Procedure

Step 1: Computational Pre-screening of Mimetic Analogs

- Perform molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulations to pre-evaluate the possibility of substituting zearalenone with mimetic analogs

- Determine optimal template molecule concentrations for the imprinting process

Step 2: Surface Modification of SiO₂ Particles

- Activate SiO₂ particles with 0.1M HCl for 1 hour at room temperature with continuous shaking

- Wash particles with deionized water until neutral pH is achieved

- Dry activated particles at 60°C for 12 hours

Step 3: Protein Imprinting with Mimetic Analogs

- Prepare template solution by dissolving BSA (1-5 mg/mL) in PBS buffer (pH 7.4)

- Add selected mimetic analog (coumarin, 4-hydroxycoumarin, quercetin, or 5,7-dimethoxycoumarin) at predetermined concentrations

- Incubate template mixture with modified SiO₂ particles for 2 hours at 25°C with gentle shaking

Step 4: Cross-linking and Cavity Stabilization

- Add glutaraldehyde solution (0.5% v/v) to the protein-particle mixture

- Incubate for 4 hours at 4°C to facilitate cross-linking

- Centrifuge at 5000 × g for 10 minutes and collect the sorbent

Step 5: Template Removal

- Wash sorbent repeatedly with acetate buffer (pH 4.0) containing 0.1% SDS

- Continue washing until no protein or mimetic analog is detected in the supernatant (verify by UV-Vis spectroscopy)

- Rinse with deionized water and freeze-dry the final bioinorganic sorbent

Step 6: Quality Control

- Determine sorption capacity using model solutions of template molecules

- Validate specificity and imprinting factor (IF) against control sorbents

Protocol 2: Sorption Studies and Solid-Phase Extraction

This protocol describes the evaluation of sorption capacity and application of the prepared bioinorganic sorbent for solid-phase extraction [1].

Materials and Equipment

- Sorbent: Bioinorganic sorbent prepared in Protocol 1

- Target analytes: Zearalenone, coumarin derivatives, quercetin

- Matrix samples: Wheat extract, model solutions

- Equipment: HPLC system with fluorescence detector, vacuum manifold, SPE cartridges

Procedure

Step 1: Sorption Isotherm Studies

- Prepare standard solutions of target analytes at concentrations ranging from 0.1 to 100 mg/L

- Add fixed amount of sorbent (10 mg) to each solution

- Incubate for 2 hours at 25°C with continuous shaking

- Centrifuge and analyze supernatant concentration by HPLC

- Calculate sorption capacity (Q) using the formula: Q = (C₀ - Cₑ) × V/m, where C₀ and Cₑ are initial and equilibrium concentrations, V is solution volume, and m is sorbent mass

- Fit data to Langmuir and Freundlich isotherm models

Step 2: Solid-Phase Extraction Procedure

- Pack SPE cartridges with 50 mg of bioinorganic sorbent

- Condition with 3 mL methanol followed by 3 mL deionized water

- Load sample (wheat extract or model solution) at controlled flow rate of 1 mL/min

- Wash with 3 mL deionized water to remove interferents

- Elute target analytes with 2 mL methanol:acetic acid (9:1 v/v)

- Evaporate eluent under nitrogen stream and reconstitute in mobile phase for HPLC analysis

Step 3: HPLC Analysis

- Column: C18 reverse-phase column (150 × 4.6 mm, 5 μm)

- Mobile phase: Acetonitrile:water with 0.1% formic acid (gradient elution)

- Flow rate: 1.0 mL/min

- Detection: Fluorescence detection (λex = 270 nm, λem = 460 nm for zearalenone)

- Injection volume: 20 μL

Step 4: Method Validation

- Determine linearity, limit of detection (LOD), limit of quantification (LOQ)

- Calculate precision (intra-day and inter-day RSD) and accuracy (recovery %)

- Assess selectivity against structurally similar compounds

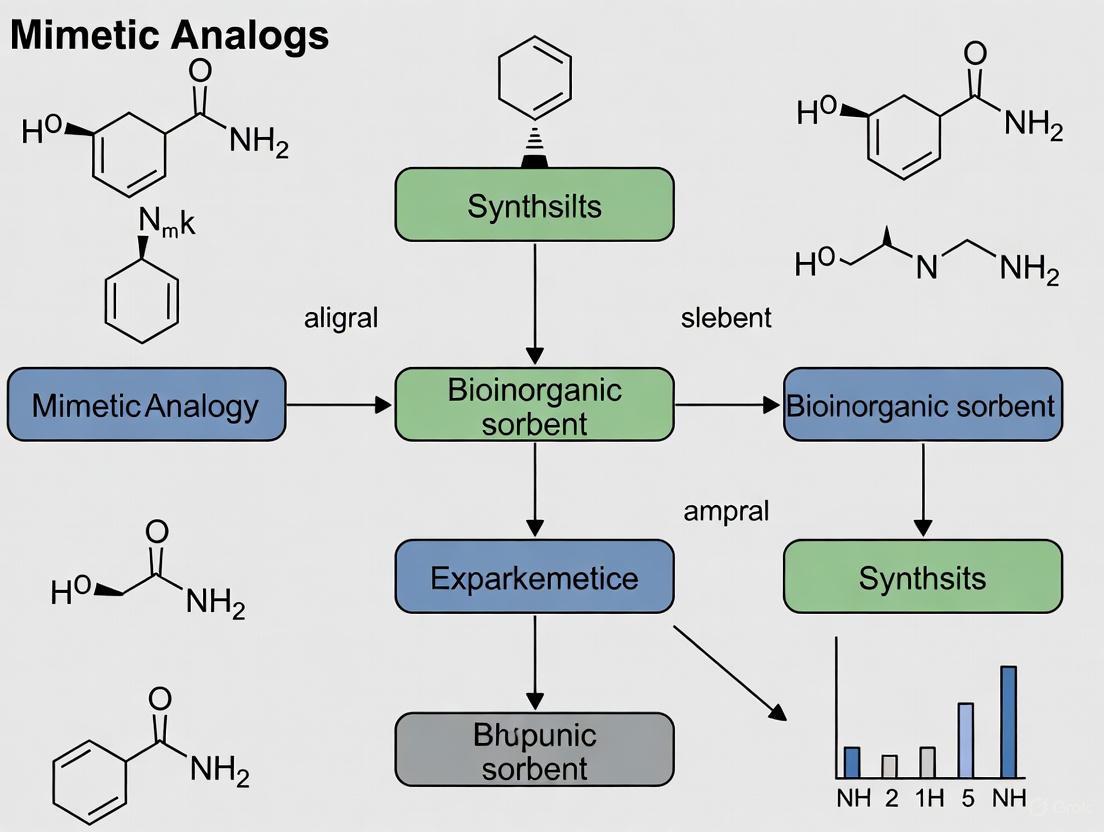

Signaling Pathways and Workflow Visualization

Sorbent Development and Application Workflow

Molecular Recognition Mechanism

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Bioinorganic Sorbent Development

| Reagent/Material | Function/Purpose | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Silicon Dioxide (SiO₂) Particles | Inorganic support material with high surface area and mechanical stability | Base matrix for sorbent preparation [1] |

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) | Template protein for molecular imprinting | Creates specific binding cavities during imprinting process [1] |

| Coumarin Derivatives | Mimetic analogs of target compounds (e.g., zearalenone) | Safer alternatives for optimization of imprinting conditions [1] |

| Glutaraldehyde | Cross-linking agent for protein stabilization | Fixes imprinted structure and enhances sorbent durability [1] |

| Porphyrins and Metalloporphyrins | Complexing agents for metal ion coordination | Selective sorption of heavy metal ions [2] |

| Hydrogel Polymers | Three-dimensional network for analyte entrapment | Extraction of analytes from complex matrices [3] |

| Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) | Porous sorbents with tunable properties | Sample preparation and preconcentration of analytes [4] |

| Modified Zeolites | Mineral sorbents for ion exchange | Heavy metal removal from aqueous solutions [5] |

| Synthetic Cationites (Puromet MTS9300/9301) | High-capacity ion exchange resins | Monitoring heavy metal pollution in surface waters [5] |

The selection of appropriate research reagents is critical for developing effective bioinorganic sorbents. The inorganic support material, typically silicon dioxide particles, provides mechanical stability and high surface area for functionalization [1]. The template protein (e.g., BSA) and mimetic analogs work in concert to create specific recognition sites, while cross-linking agents like glutaraldehyde preserve the structural integrity of these sites during operational use. For metal ion sorption applications, porphyrin-based compounds offer exceptional coordination capabilities, with their tetrapyrrole structure providing strong binding affinity for various metal ions [2]. The integration of these components through careful optimization creates sorbent materials with tailored selectivity for specific analytical or remediation applications.

Metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) are crystalline porous materials composed of metal ions or clusters coordinated with organic linkers to form one-, two-, or three-dimensional structures [6] [7]. Their exceptional porosity, tunable chemistry, and structural diversity make them outstanding platforms for sorption applications. The structure-property relationships in MOFs directly govern their sorption behavior, with parameters such as surface area, pore size, chemical functionality, and framework flexibility dictating interactions with target analytes. Within the context of developing mimetic analogs for bioinorganic sorbent preparation, MOFs offer a unique bridge between inorganic materials and biological systems. By incorporating biomimetic design principles or biological building blocks, researchers can create selective sorbents that mimic natural recognition processes for advanced separation and sensing applications [8].

Fundamental MOF Engineering Strategies for Enhanced Sorption

The sorption performance of MOFs can be systematically enhanced through targeted structural modifications that optimize host-guest interactions. These engineering strategies manipulate the framework's chemical and physical properties to improve capacity, selectivity, and stability.

Chemical Functionalization Strategies

Chemical modification of MOF constituents represents a powerful approach for tuning sorption properties. The selection of metal centers and organic ligands directly influences the framework's affinity for specific analytes.

Metal Center Modulation: Open metal sites (OMSs) function as strong adsorption centers by providing localized, high-energy binding sites. These coordinatively unsaturated sites are generated by removing terminal solvent molecules from metal clusters, creating areas of enhanced Lewis acidity that strongly interact with polarizable molecules like CO₂ and water vapor [6]. Different metal centers within isostructural frameworks significantly impact sorption performance; for instance, in MIL-101 variants, Al and Sc versions exhibit superior CO₂ uptake compared to Cr, Mn, Fe, Ti, or V analogs due to more favorable local electronic environments [9].

Ligand Engineering: Organic ligands can be functionalized with specific chemical groups that enhance analyte-framework interactions through various mechanisms:

- Amino groups (-NH₂) improve CO₂ capture through acid-base interactions and hydrogen bonding [6].

- Hydroxyl groups (-OH) provide hydrogen bond donors for enhanced water sorption [10].

- Biofunctional ligands incorporating amino acids, nucleobases, or other biological molecules introduce chiral environments, multiple coordination modes, and biocompatibility for selective molecular recognition [8].

Table 1: MOF Engineering Strategies and Their Impact on Sorption Properties

| Engineering Strategy | Specific Modification | Impact on Sorption Properties | Example MOFs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metal Center Selection | Introduction of open metal sites | Creates strong adsorption centers for polar molecules; enhances Lewis acid-base interactions | MOF-74, HKUST-1 [6] |

| Ligand Functionalization | Amino group incorporation | Enhances CO₂ capture via acid-base interactions | UiO-66-NH₂ [6] |

| Ligand Extension | Longer aromatic ligands | Increases pore volume and promotes π-CO₂ interactions; enhances capacity | Extended MIL-101 [9] |

| Biomimetic Design | Amino acids, nucleobases | Provides chiral environments, multiple functional groups, biocompatibility | Bio-MOFs [8] |

| Pore Size Control | Ligand length adjustment, interpenetration | Enables size-selective sorption; molecular sieving | ZIF-8 [6] |

| Composite Formation | Incorporation of nanostructures | Enhances sensitivity, selectivity, and stability | MOF-nanoparticle composites [7] |

Structural and Morphological Control

Beyond chemical composition, the three-dimensional architecture of MOFs profoundly influences mass transport and accessibility to internal surfaces.

Pore Size Engineering: Varying the length and geometry of organic linkers enables precise control over pore aperture dimensions. This allows for size-selective sorption through molecular sieving effects, where only molecules below a specific critical diameter can access the internal pore volume [6]. Additionally, framework interpenetration can be strategically employed to create narrow channels and enhanced selectivity, though this often reduces overall capacity [6].

Hierarchical Pore Structures: Creating multimodal pore size distributions incorporating both microporous and mesoporous domains optimizes sorption kinetics and capacity. Mesopores facilitate rapid molecular diffusion to active sites, while micropores provide high surface area for substantial uptake [6].

Quantitative Structure-Property Relationships in MOF Sorption

The relationship between MOF structural parameters and sorption performance can be quantified through systematic analysis, providing design principles for targeted applications.

Water Sorption Properties

Water adsorption in MOFs exhibits complex behaviors governed by framework hydrophilicity, pore size, and hydrogen-bonding environments. A comprehensive study of >200 MOFs revealed seven distinct isotherm types, with S-shaped isotherms being particularly desirable for atmospheric water harvesting applications due to their steep uptake within narrow relative humidity windows [10].

Table 2: Structural Properties Governing Water Adsorption Behavior in MOFs

| Structural Parameter | Impact on Water Adsorption | Optimal Values for AWH | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heat of Adsorption (HoA) | Determines regeneration energy; controls isotherm shape | ~40-60 kJ/mol (moderate) | MOFs with HoA <40 kJ/mol show low uptake; >60 kJ/mol requires high regeneration temp [10] |

| Pore Size | Governs capillary condensation pressure; affects isotherm steepness | >10 Å for sharp transitions | Larger pores promote sharper uptake steps due to cooperative filling [10] |

| Adsorption Site Uniformity | Influences step pressure and isotherm shape | High uniformity for low RH operation | More homogeneous sites yield lower step pressures [10] |

| Channel Dimensionality | Affects water cluster formation and transport | 3D for rapid kinetics | Higher dimensionality facilitates faster adsorption/desorption [10] |

| Functional Groups | Controls initial water nucleation | -OH, -COOH for low-RH uptake | MOF-801 with -OH groups initiates adsorption at low RH [10] |

The step pressure (relative humidity where steep uptake occurs) is critically influenced by both the uniformity of adsorption sites and pore chemistry. MOFs with more homogeneous binding sites exhibit lower step pressures, making them suitable for water harvesting in arid environments [10].

CO₂ Sorption Performance

CO₂ capture performance in MOFs depends on a balance between physisorption strength and specific chemical interactions. In MIL-101 systems, longer aromatic ligands generally enhance CO₂ uptake by increasing pore volume and promoting π-CO₂ interactions, while compact ligands favor stronger local affinity but lower overall capacity [9]. Spatial density mapping reveals preferential CO₂ adsorption sites near tetrahedral cavities and metal nodes, with the local chemical environment significantly influencing binding strength [9].

Experimental Protocols for MOF-Based Sorption Studies

Protocol: Biomimetic MOF Synthesis for Selective Sorption

Principle: This protocol describes the preparation of amino acid-functionalized bio-MOFs for selective sorption applications, particularly valuable for chiral separations or biomolecule capture [8].

Materials:

- Metal salts (e.g., Zn(NO₃)₂·6H₂O, Cu(BF₄)₂)

- Amino acid ligands (e.g., histidine, methionine, cysteine)

- Solvents: N,N-Dimethylformamide (DMF), methanol, deionized water

- Modulators: acetic acid, benzoic acid

Procedure:

- Precursor Preparation: Dissolve metal salt (0.5 mmol) and amino acid (1.0 mmol) in 20 mL of DMF/water mixture (3:1 v/v) in a scintillation vial.

- Modulator Addition: Add 0.5 mL of acetic acid as a modulator to control crystallization kinetics.

- Solvothermal Reaction: Seal the vial and heat at 85°C for 24 hours in an oven.

- Product Recovery: Cool the vial to room temperature naturally. Collect crystals by vacuum filtration.

- Activation: Wash crystals with DMF (3 × 10 mL) and methanol (3 × 10 mL), then activate under vacuum at 100°C for 6 hours.

- Characterization: Confirm structure by PXRD, analyze porosity by N₂ sorption at 77K, and verify functionalization by FT-IR spectroscopy.

Quality Control: PXRD pattern should match simulated pattern from single-crystal data. BET surface area typically ranges from 500-2000 m²/g depending on the amino acid ligand.

Protocol: Sorption Isotherm Measurement Using Gravimetric Analysis

Principle: This protocol details the measurement of water vapor sorption isotherms for MOF materials, critical for evaluating their performance in atmospheric water harvesting applications [10].

Materials:

- Activated MOF sample (≥50 mg)

- Humidity-controlled chamber

- High-precision microbalance (sensitivity ≤ 0.1 μg)

- Temperature control system (±0.1°C)

- Dry N₂ gas, water vapor source

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Weigh empty sample pan. Add activated MOF sample (20-50 mg) and record exact mass.

- System Conditioning: Place sample in sorption analyzer and degas at 100°C under vacuum until constant mass is achieved (typically 6-12 hours).

- Isotherm Measurement: Set temperature to 25°C. Begin measurements at 0% relative pressure (P/P₀), incrementally increasing P/P₀ in steps of 0.05.

- Equilibration Criteria: At each pressure point, monitor mass change until equilibrium is reached (dm/dt < 0.01% per minute for 10 consecutive minutes).

- Data Collection: Record equilibrium mass at each P/P₀ point. Continue measurements up to P/P₀ = 0.95.

- Desorption Branch: Reverse the process by systematically decreasing P/P₀ to complete the hysteresis loop.

Data Analysis: Plot uptake (mg/g or mmol/g) versus relative pressure (P/P₀). Classify isotherm shape according to IUPAC classification. Calculate deliverable capacity as the difference between uptake at P/P₀ = 0.8 and P/P₀ = 0.2 for water harvesting applications.

Biomimetic and Bioinorganic Applications

The integration of biological components with MOF structures creates hybrid materials with enhanced molecular recognition capabilities for specialized sorption applications.

Bioaffinity-Based MOFs for Analytical Separations

Bio-MOFs incorporating biological ligands exhibit unique selectivity profiles valuable for challenging separations:

- Amino acid-functionalized MOFs: Histidine-containing MOFs demonstrate enantioselectivity for chiral alcohols, with extraction efficiencies of 76% for the R-enantiomer of 1-phenylethanol [8].

- Nucleobase-incorporated frameworks: Adenine-containing MOFs selectively capture specific pharmaceuticals from complex matrices through complementary hydrogen bonding [8].

- Carbohydrate-decorated MOFs: Glucose-functionalized ZIF-8 shows enhanced selectivity for glycopeptides through multivalent interactions [8].

Biomimetic Sensing Platforms

MOFs functionalized with biological recognition elements enable highly selective detection systems:

- Aptamer-MOF conjugates: DNA aptamers grafted onto MOF surfaces provide specific binding pockets for small molecules, proteins, and cells, translating molecular recognition into measurable optical or electrochemical signals [7].

- Antibody-immobilized MOFs: Antibodies attached to MOF surfaces through carbodiimide chemistry enable capture and detection of specific antigens in complex biological samples [8].

- Enzyme-mimetic MOFs: MOFs with peroxidase-like activity (e.g., ZIF-67, MIL-53) catalyze colorimetric reactions for biomarker detection, functioning as robust alternatives to natural enzymes in ELISA-like assays [7].

Visualization of MOF Sorption Relationships

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for MOF-Based Sorption Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Purpose | Application Examples | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metal Salts (Zn²⁺, Cu²⁺, Cr³⁺, Zr⁴⁺) | Provide metal nodes for framework construction | Zn(NO₃)₂ for ZIF synthesis; ZrCl₄ for UiO series | Oxidation state determines coordination geometry; impacts stability [6] |

| Organic Linkers (carboxylic acids, azoles) | Bridge metal nodes to form framework structure | Terephthalic acid (MIL series); 2-methylimidazole (ZIF-8) | Length dictates pore size; functionality governs interactions [9] |

| Amino Acid Ligands (histidine, cysteine) | Introduce chirality, biocompatibility, specific interactions | Histidine for chiral separations; cysteine for metal capture [8] | Multiple coordination modes; inherent chirality enables enantioselectivity [8] |

| Modulators (acetic acid, benzoic acid) | Control crystallization kinetics and crystal size | Acetic acid for UiO-66; benzoic acid for HKUST-1 | Concentration affects defect density and surface area [8] |

| Solvents (DMF, DEF, water) | Medium for solvothermal synthesis | DMF for most solvothermal reactions; water for green synthesis | Polarity affects solubility; boiling point determines reaction temperature [6] |

| Activation Agents (methanol, acetone) | Remove solvent from pores during activation | Methanol for solvent exchange; supercritical CO₂ | Low surface tension minimizes framework collapse [10] |

The structure-property relationships governing sorption in MOFs provide a robust foundation for designing advanced materials with tailored performance. Through strategic engineering of metal nodes, organic linkers, pore architecture, and biomimetic functionalities, researchers can precisely control host-guest interactions to optimize capacity, selectivity, and kinetics for specific sorption applications. The integration of biological recognition elements with synthetic framework structures is particularly promising for developing next-generation mimetic analogs that bridge the gap between inorganic materials and biological systems. As computational screening methods advance and our understanding of structure-property relationships deepens, the rational design of MOF-based sorbents will continue to evolve, enabling sophisticated solutions to complex separation challenges in environmental remediation, analytical chemistry, and biomedical applications.

Polyoxometalates (POMs) are a class of nanosized, soluble molecular metal-oxo clusters with well-defined structures, typically composed of early transition metals such as molybdenum (Mo), tungsten (W), vanadium (V), and niobium (Nb) in their highest oxidation states [11] [12]. Their structural framework consists of an array of corner-sharing and edge-sharing pseudo-octahedral MO6 units [11]. These inorganic compounds have attracted significant scientific interest due to their remarkable redox properties, chemical stability, and catalytic versatility. A particularly emerging application lies in their ability to mimic the function of natural laccase enzymes [11] [12]. Natural laccases are multi-copper oxidases that catalyze the one-electron oxidation of a broad range of phenolic substrates while reducing oxygen to water [13]. While highly effective, natural laccases suffer from inherent instability, difficult recovery, and high costs, which limit their practical applications [14]. Laccase-mimetic POMs offer a robust, cost-effective alternative, capable of operating under harsh conditions of temperature, pressure, and pH where natural enzymes would denature [11]. Their exploration is providing key insights for the degradation of emergent water contaminants and the development of advanced bioinorganic sorbents [11].

Mechanism of Action and Functional Analogy

The enzyme-like functionality of POMs stems from a functional analogy with natural laccases, primarily their ability to use oxygen as an electron acceptor [11]. The following diagram illustrates the core catalytic analogy between natural laccases and laccase-mimetic POMs.

Comparative Catalytic Pathways of Laccases and POMs

The core reaction involves a one-electron oxidation of the substrate (e.g., a phenolic endocrine disruptor) by the POM, which itself is reduced. The reduced POM is subsequently re-oxidized by molecular oxygen (O₂), completing the catalytic cycle with water as the sole by-product [11] [12]. This redox cycling makes the process clean and environmentally friendly. For instance, in the oxidation of the mustard gas simulant 2-chloroethyl ethyl sulfide (CEES), specific POM structures like {Mo₇₂V₃₀} interact with oxidants like H₂O₂ to generate active peroxo species (e.g., peroxomolybdenum and peroxovanadium) that attack the sulfur atom of CEES, selectively converting it into a non-toxic sulfoxide [15]. The metal composition within the POM structure is critical; studies on nanopolyoxometalate clusters have shown a distinct activity order of V > Cr > Fe > Mo for CEES oxidation, underscoring the importance of the choice of transition metal in designing effective laccase mimics [15].

Quantitative Performance Data of Representative POMs

The catalytic efficiency of laccase-mimetic POMs has been quantitatively demonstrated in the degradation of various pollutants. The table below summarizes key performance metrics for selected POM structures against different substrates.

Table 1: Catalytic Performance of Selected Laccase-Mimetic POMs

| POM Structure | Target Substrate | Experimental Conditions | Key Performance Metrics | Reference / Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CoPMo₆O₂₁ (Cs₄[Co(H₂O)₄][PMo₆O₂₁(PABA)₃]₂) | CEES (Mustard gas simulant) | 12 min reaction time, H₂O₂ oxidant | 98.8% Conversion, 99.0% selectivity to non-toxic CEESO | [15] |

| {Mo₇₂V₃₀} (Na₈K₁₄(VO)₂[K₁₀⊂{Mo(Mo)₅O₂₁(H₂O)₃(SO₄)}₁₂{(VO)₃₀(H₂O)₂₀]) | CEES (Mustard gas simulant) | 10 min reaction time, ~20°C, H₂O₂:CEES (1:1) | 99.45% Conversion; Kinetic constant (k) = 0.56 min⁻¹ | [15] |

| {Mo₇₂Cr₃₀} | CEES (Mustard gas simulant) | 1 min reaction time, ~20°C | 51.42% Conversion; Kinetic constant (k) = 0.53 min⁻¹ | [15] |

| Polyoxovanadates (Example) | Phenolic Endocrine Disruptors (e.g., Bisphenol A) | Not specified in detail | Effective degradation highlighted as a key example | [11] [12] |

| Carboxylic acid-modified POMs (Co, Mn, Ni, Zn) | Methyl Phenyl Sulfide (Model substrate) | 20 min reaction time, H₂O₂ oxidant | Up to 98% Selectivity to sulfoxide (CoPMo₆O₂₁) | [15] |

The data reveals that certain POMs achieve near-complete contaminant conversion with high selectivity for less harmful products. The kinetic constants further provide a quantitative basis for comparing the intrinsic activity of different POM structures, which is vital for selecting materials for specific decontamination applications.

Application Notes: Degradation of Endocrine Disruptors

A primary application driving the development of laccase-mimetic POMs is the remediation of endocrine disrupting compounds (EDCs) from water bodies [11] [12]. EDCs, such as bisphenol A (BPA), phthalates, and various pesticides, are notorious for their persistence, low degradability, and ability to interfere with hormonal systems in vertebrates and invertebrates even at low doses [11] [12]. POMs offer a potent catalytic solution for their breakdown. The protocol leverages the POM's ability to catalyze the oxidative degradation of these phenolic pollutants. The process is efficient because POMs can directly catalyze the same substrates as laccases but are more cost-effective and robust for large-scale production and application in potentially harsh environmental conditions [11] [12]. The workflow for this application is methodical, from POM selection to post-treatment analysis, as outlined below.

EDC Degradation Workflow Using POMs

Detailed Experimental Protocol: POM-Mediated Degradation of Phenolic Contaminants

Objective: To quantitatively assess the efficiency of a selected Polyoxometalate (POM) in degrading a model phenolic endocrine disruptor (e.g, Bisphenol A) in an aqueous solution.

Materials:

- Catalyst: Selected POM (e.g., a polyoxovanadate cluster, {Mo₇₂V₃₀}, or CoPMo₆O₂₁).

- Substrate: Stock solution of the target contaminant (e.g., 1 mM Bisphenol A in purified water or a suitable organic solvent like methanol, with final solvent concentration <1% v/v).

- Buffer: Appropriate buffer solution (e.g., 50 mM sodium acetate buffer, pH 4.5-5.0, to mimic laccase optimum conditions, unless testing pH stability).

- Oxidant: (If required) Hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂) solution of known concentration.

- Equipment: Thermostated shaking incubator, HPLC system with UV/Vis or PDA detector, analytical column (e.g., C18 reverse-phase), and standard glassware.

Procedure:

- Reaction Setup: In a series of glass vials, prepare the reaction mixtures containing:

- 980 µL of buffer solution.

- 10 µL of the contaminant stock solution (Final concentration: 10 µM).

- 10 µL of a concentrated POM aqueous stock solution (Final POM concentration: e.g., 0.1-1.0 mg/mL).

- Control 1: Replace POM solution with 10 µL of water (to account for any abiotic degradation).

- Control 2: Include POM but exclude the oxidant (if H₂O₂ is used), or vice versa, to establish the necessity of each component.

- Initiation and Incubation: Cap the vials and place them in a thermostated shaking incubator pre-set to the desired temperature (e.g., 25°C or 30°C). Start the reaction by adding the oxidant (if applicable) and maintain constant agitation (e.g., 150 rpm).

- Sampling: At predetermined time intervals (e.g., 0, 5, 15, 30, 60, 120 min), withdraw aliquots (e.g., 100 µL) from the reaction vial.

- Reaction Quenching: Immediately mix the aliquot with an equal volume of a quenching agent (e.g., methanol or acetonitrile) to stop the reaction. Optionally, filter the quenched sample through a 0.22 µm syringe filter to remove any particulate matter before analysis.

- Analysis: Analyze the quenched samples using HPLC to quantify the remaining concentration of the parent contaminant. Calculate the degradation percentage and pseudo-first-order rate constants based on the decline in contaminant concentration over time.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The experimental work on laccase-mimetic POMs relies on a specific set of reagents and materials. The following table catalogues the essential components of a research toolkit for this field.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for Investigating Laccase-Mimetic POMs

| Reagent/Material | Function and Role in Research | Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| POM Catalysts | The core catalytic element that mimics laccase activity. | e.g., {Mo₇₂V₃₀}, {Mo₇₂Cr₃₀}, CoPMo₆O₂₁, Polyoxovanadates. Synthesis can be optimized using modern in situ techniques [16]. |

| Target Contaminants | Substrates for evaluating catalytic performance and efficiency. | Phenolic EDCs (Bisphenol A), thioethers (CEES as a vesicant simulant), synthetic dyes, organic sulfides [11] [15]. |

| Oxygen Source / Oxidant | Terminal electron acceptor required for the catalytic cycle. | Molecular oxygen (via aeration) or hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂). The choice affects the reaction mechanism and rate [11] [15]. |

| Buffer Solutions | Maintain constant pH, a critical parameter for catalytic activity and stability. | Sodium acetate buffer (for acidic pH), phosphate buffers. Stability under harsh conditions is a key POM advantage [11]. |

| Characterization Tools | For structural analysis and verification of catalytic mechanisms. | X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) to monitor metal valence states [15]; UV-Vis spectroscopy to detect intermediates [15]. |

| Analytical Chromatography | To separate, identify, and quantify reaction substrates and products. | High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) is standard for tracking degradation kinetics and product formation [15]. |

Laccase-mimetic POMs represent a convergent point of bioinorganic chemistry and materials science, offering a pathway to robust, cost-effective, and highly functional analogs of natural enzymes. Their demonstrated efficacy in degrading resilient environmental contaminants like endocrine disruptors and chemical warfare agent simulants underscores their potential for integration into advanced sorbent and filtration systems [11] [15]. Future research will likely focus on the rational design of POMs with optimized copper-mimetic active sites [14], their incorporation into larger composite materials and frameworks for enhanced stability and reusability [15] [17], and the expansion of their application into biosensing and therapeutic areas [18] [17]. The continued exploration of these versatile inorganic clusters is poised to make significant contributions to the development of sophisticated mimetic analogs for bioinorganic sorbent preparation and beyond.

Green-Synthesized Metal Nanoparticles as Bioinspired Sorbents

The development of bioinspired sorbents represents a frontier in separation science, offering sustainable alternatives to conventional materials. Within this domain, green-synthesized metal nanoparticles (G-MNPs) have emerged as particularly promising building blocks for advanced sorbent systems. These nanoparticles are produced through environmentally benign, cost-effective biological pathways utilizing plant extracts, microorganisms, or biomolecules rather than toxic chemicals [19] [20]. This green synthesis approach aligns with the principles of green chemistry and sustainable technology, minimizing hazardous waste while producing nanoparticles with excellent biocompatibility and surface functionality [21].

The bioinspired nature of G-MNPs stems from their synthesis mechanisms, which often mimic natural mineralization processes. Biological entities contain a diverse array of phytochemicals, enzymes, and proteins that serve dual roles as reducing agents and stabilizing capping ligands during nanoparticle formation [19] [22]. This biological capping imparts functional groups that enhance sorption capabilities and provides a platform for further modification using mimetic analogs—synthetic molecules designed to mimic biological recognition elements [23]. When integrated into composite sorbents, these bioinspired nanoparticles create systems with superior selectivity, capacity, and regenerability for target analytes.

This document provides comprehensive application notes and experimental protocols for leveraging G-MNPs as bioinspired sorbents within research frameworks focused on mimetic analog development for bioinorganic sorbent preparation. It addresses the full workflow from nanoparticle synthesis and characterization to sorbent fabrication and performance evaluation, with particular emphasis on standardized methodologies essential for research reproducibility and translational development.

Synthesis Protocols for Green Metal Nanoparticles

Plant-Mediated Synthesis

Plant-mediated synthesis represents the most widely utilized approach for G-MNP production due to its simplicity, scalability, and rich diversity of phytochemicals [19] [22].

Protocol: Silver Nanoparticle Synthesis Using Citrus Peel Extract

- Reagents Required: Fresh citrus peels (orange, lemon, or lime), silver nitrate (AgNO₃) solution (1-10 mM), deionized water, ethanol (70% v/v).

- Equipment Needed: Blender, filtration setup (cheesecloth and Whatman No. 1 filter paper), magnetic stirrer with hotplate, ultraviolet-visible (UV-Vis) spectrophotometer, temperature-controlled incubator.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Plant Extract Preparation:

- Wash 100 g of fresh citrus peels thoroughly with deionized water to remove surface contaminants.

- Macerate the peels using a blender with 200 mL of deionized water or ethanol.

- Heat the mixture at 60°C for 15-20 minutes with continuous stirring at 500 rpm to enhance phytochemical extraction.

- Filter the resulting extract through cheesecloth followed by Whatman No. 1 filter paper to obtain a clear solution.

- Store the extract at 4°C for a maximum of one week [24].

Nanoparticle Synthesis:

- Combine the citrus peel extract with 1 mM AgNO₃ solution in a 1:9 ratio (extract:AgNO₃) in a glass vessel.

- Incubate the reaction mixture at 25-30°C for 2-24 hours with continuous stirring at 300 rpm.

- Monitor the synthesis progression through visual color change (colorless to yellowish-brown) and UV-Vis spectral analysis (400-450 nm peak) [19] [22].

- Recover nanoparticles by centrifugation at 12,000 rpm for 20 minutes, followed by washing with deionized water three times to remove unreacted components.

- Resuspend the purified nanoparticles in deionized water and store at 4°C for further use [19].

Critical Parameters: Extract concentration, metal salt concentration, reaction temperature, pH (optimize between 5-9), and reaction time significantly influence nanoparticle size, morphology, and stability [19]. Standardization of these parameters is essential for batch-to-batch reproducibility.

Microorganism-Assisted Synthesis

Microbial synthesis employs bacteria, fungi, or algae for intracellular or extracellular nanoparticle production through enzymatic reduction [19] [22].

Protocol: Fungal-Mediated Gold Nanoparticle Synthesis

- Reagents: Fungal strain (e.g., Aspergillus fumigatus), chloroauric acid (HAuCl₄) solution (1 mM), culture medium (Potato Dextrose Agar/Broth), deionized water.

- Equipment: Autoclave, laminar flow hood, orbital shaker incubator, centrifugation equipment.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Biomass Preparation:

- Cultivate the fungal strain in appropriate liquid medium at 28°C for 72-96 hours in an orbital shaker at 150 rpm.

- Harvest the biomass by filtration through Whatman filter paper and wash thoroughly with sterile deionized water to remove media components [22].

- Resuspend approximately 10 g of wet biomass in 100 mL of deionized water.

Nanoparticle Synthesis:

- Add 1 mM HAuCl₄ solution to the biomass suspension to achieve a final concentration of 0.5 mM.

- Incubate the mixture at 28°C for 24-72 hours with continuous shaking at 120 rpm.

- Monitor synthesis through color change (pale yellow to purple) and UV-Vis analysis (520-550 nm peak).

- For extracellular synthesis, filter the mixture to separate biomass, then recover nanoparticles from the filtrate by centrifugation at 15,000 rpm for 30 minutes.

- For intracellular synthesis, disrupt the biomass using sonication or enzymatic treatment before nanoparticle recovery [19] [22].

Critical Parameters: Microbial strain selection, culture age, metal salt concentration, incubation conditions (temperature, pH, agitation), and biomass processing method significantly impact nanoparticle characteristics.

Characterization Techniques for G-MNPs

Comprehensive characterization is essential to correlate G-MNP properties with sorbent performance. The following table summarizes key characterization techniques and their applications:

Table 1: Characterization Techniques for Green-Synthesized Metal Nanoparticles

| Technique | Information Obtained | Experimental Parameters | Significance for Sorbent Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| UV-Vis Spectroscopy | Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) peak, stability, preliminary size assessment | Wavelength range: 300-800 nm; resolution: 1 nm | SPR indicates formation; peak shift indicates aggregation or functionalization [20] |

| Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) | Size, size distribution, shape, morphology | Acceleration voltage: 80-200 kV; sample preparation: grid coating | Size/shape directly influences surface area and active sites [20] |

| Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) | Surface morphology, topography, elemental composition | Acceleration voltage: 5-30 kV; coating: gold/carbon | Reveals surface texture and porosity for analyte interaction [25] [20] |

| Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) | Functional groups, biomolecular capping, stabilization mechanisms | Wavelength range: 400-4000 cm⁻¹; resolution: 4 cm⁻¹ | Identifies surface chemistry for modification and analyte binding [25] [20] |

| X-ray Diffraction (XRD) | Crystalline structure, phase identification, crystallite size | Radiation: Cu Kα; 2θ range: 20-80° | Crystal structure affects chemical stability and reactivity [20] |

| X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) | Elemental composition, oxidation states, surface chemistry | Source: Al Kα; pass energy: 20-100 eV | Quantifies elemental makeup and oxidation states for sorption mechanisms [20] |

| Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) | Hydrodynamic size, size distribution, colloidal stability | Measurement angle: 173°; temperature control: ±0.1°C | Determines stability in suspension for composite formation [19] |

Sorbent Fabrication and Functionalization Protocols

Composite Sorbent Fabrication

Integrating G-MNPs into robust, usable sorbent formats is crucial for practical applications. The following protocol details the fabrication of chitosan-based composite sorbents incorporating G-MNPs:

Protocol: Fabrication of Chitosan/Fe@PDA Sorbent Beads

- Reagents: Chitosan (CS, high molecular weight), Fe(NO₃)₃ standard solution, 3-hydroxytyramine hydrochloride (dopamine), lysine, Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.5), glutaraldehyde solution (25%), dishwasher solution (surfactant-based) [25].

- Equipment: Ultrasonic bath, magnetic stirrer, centrifugation equipment, pH meter, syringe pump (optional).

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Polydopamine Nanoparticle (PDA NP) Synthesis:

- Dissolve 10 mM dopamine and 10 mM lysine in 50 mL of Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.5).

- Stir vigorously for 3 days at room temperature under ambient conditions to facilitate polymerization and NP formation.

- Recover PDA NPs by centrifugation at 10,000 rpm for 20 minutes.

- Wash the pellet three times with ultrapure water to remove salts and residual monomers, redispersing after each wash [25].

Chitosan-Iron Mixture Preparation:

- Disperse 2 g of chitosan powder in 50 mL of 1000 mg L⁻¹ Fe(NO₃)₃ solution using ultrasonication for 30 minutes to achieve a homogeneous blend (CS/Fe) [25].

Composite Formation and Bead Generation:

- Blend the prepared PDA NPs with the CS/Fe mixture using ultrasonication to achieve homogeneity.

- Prepare a crosslinking solution by mixing 5 mL of 25% glutaraldehyde, 5 mL of dishwasher solution (acts as surfactant to prevent aggregation), and 40 mL of ultrapure water.

- Add the CS/Fe/PDA mixture dropwise into the crosslinking solution using a syringe pump to form spherical beads.

- Allow the beads to cure in the crosslinking solution for 2 hours with gentle agitation.

- Wash the resulting CS/Fe@PDA beads thoroughly with ultrapure water and store in a moist environment at 4°C [25].

Critical Parameters: Chitosan molecular weight and concentration, Fe³⁺ concentration, PDA NP to chitosan ratio, crosslinking density, bead size uniformity.

Functionalization with Mimetic Analogs

Surface functionalization with mimetic analogs enhances sorbent selectivity toward specific target analytes.

Protocol: G-MNP Functionalization with Molecular Imprints

- Reagents: G-MNPs, target analyte (template molecule), functional monomer (e.g., methacrylic acid), crosslinker (e.g., ethylene glycol dimethacrylate), initiator (e.g., azobisisobutyronitrile - AIBN), appropriate solvent.

- Equipment: Nitrogen purge system, thermostatic water bath, rotary evaporator.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Pre-Complex Formation:

- Dissolve the template molecule and functional monomer in a suitable solvent at optimal molar ratio (typically 1:3 to 1:6 template:monomer).

- Allow pre-complexation to occur for 30-60 minutes with continuous stirring.

Polymerization:

- Add the G-MNP suspension to the pre-complex solution and disperse using ultrasonication.

- Add crosslinker (3-5 fold molar excess relative to monomer) and initiator (1% w/w relative to monomers).

- Purge the reaction mixture with nitrogen gas for 10 minutes to remove oxygen.

- Incubate at 60°C for 12-24 hours with continuous stirring to complete the polymerization.

Template Removal:

- Recover the functionalized nanoparticles by centrifugation.

- Extract the template molecule using Soxhlet extraction or repeated washing with appropriate solvent mixtures (e.g., methanol:acetic acid, 9:1 v/v).

- Verify complete template removal by analytical techniques (e.g., HPLC, UV-Vis).

- Dry the resulting molecularly imprinted G-MNPs under vacuum at 40°C [23].

Critical Parameters: Template-monomer interaction strength, template:monomer:crosslinker ratio, polymerization conditions, completeness of template extraction.

Sorbent Performance Evaluation

Quantitative Evaluation of Sorption Performance

Rigorous testing under controlled conditions is necessary to quantify sorbent efficacy. The following parameters should be systematically evaluated:

Table 2: Key Performance Metrics for G-MNP-Based Sorbents

| Performance Metric | Calculation Method | Typical Values for G-MNP Sorbents | Influencing Factors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sorption Capacity (Qe) | Qe = (C0 - Ce)V/m | Varies by target: e.g., 50-200 mg/g for antibiotics [25] | Surface area, active sites, affinity, temperature |

| Removal Efficiency (R) | R(%) = (C0 - Ce)/C0 × 100% | 70-95% for various contaminants [25] [24] | Sorbent dose, initial concentration, contact time |

| Distribution Coefficient (Kd) | Kd = (C0 - Ce)/Ce × V/m | 10²-10⁴ L/g for metal ions [24] | Selectivity, surface chemistry, solution pH |

| Selectivity Coefficient (α) | α = Kd(target)/Kd(competitor) | 2-10 for imprinted sorbents [23] | Mimetic analog design, functionalization efficiency |

| Regeneration Efficiency | Rreg(%) = Qe(regenerated)/Qe(fresh) × 100% | >80% after 5-7 cycles [25] | Sorbent stability, elution protocol |

Application Protocol: Tetracycline Antibiotic Extraction

Protocol: Solid-Phase Extraction of Tetracyclines Using CS/Fe@PDA Beads

- Reagents: CS/Fe@PDA sorbent beads, tetracycline standard solutions, methanol, acetonitrile, oxalic acid, honey/pharmaceutical samples, ultrapure water.

- Equipment: HPLC system with UV detector, vortex mixer, vacuum manifold, pH meter.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Sample Preparation:

- For honey samples: Dilute 1.0 g honey to 10 mL with ultrapure water and filter through a 0.45 μm nylon filter.

- For ointments: Dilute with ultrapure water to appropriate concentration.

- Spike samples with tetracycline standards as needed [25].

Extraction Procedure:

- Condition 0.1 g of CS/Fe@PDA beads with 3 mL methanol followed by 3 mL ultrapure water.

- Load 3 mL of sample solution (without pH adjustment) onto the sorbent.

- Vortex the mixture for 1 minute to facilitate adsorption.

- Transfer beads to a fresh tube using a filter mesh [25].

Elution and Analysis:

- Add 3 mL of elution solvent (acetonitrile:methanol:10 mM oxalic acid, 20:10:70, pH 4.0) to the beads.

- Vortex for 1 minute to desorb tetracyclines.

- Analyze the eluate using HPLC with UV detection at 355 nm.

- Separate using a C18 column with isocratic elution at 1.0 mL/min flow rate [25].

Performance Metrics: This method demonstrates linear range of 450-2000 μg L⁻¹, detection limits of 142-303 μg L⁻¹ for various tetracyclines, and maintains accuracy through ≥7 extraction-regeneration cycles [25].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for G-MNP Sorbent Development

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function | Notes for Researchers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metal Salts | AgNO3, HAuCl4, Fe(NO3)3, CuSO4, ZnCl2 | Precursors for nanoparticle synthesis | Purity affects reproducibility; prepare fresh solutions [19] [25] |

| Biological Sources | Citrus peels, plant leaves, microbial cultures (bacteria/fungi) | Provide reducing/capping agents for green synthesis | Standardize source, growth conditions, and extraction [19] [24] |

| Polymer Matrices | Chitosan, alginate, polydopamine, cellulose | Form composite sorbents; provide structural support | Biodegradable polymers enhance environmental profile [25] [24] |

| Crosslinkers | Glutaraldehyde, epichlorohydrin, genipin | Stabilize composite structures; enhance mechanical strength | Glutaraldehyde offers efficiency; explore less toxic alternatives [25] |

| Functional Monomers | Methacrylic acid, vinylpyridine, acrylamide | Create recognition sites in molecular imprinting | Choose based on template molecule chemistry [23] |

| Elution Solvents | Methanol:acetic acid, acetonitrile:acid mixtures | Desorb target analytes for sorbent regeneration | Optimize for complete recovery without sorbent damage [25] |

Experimental Workflows and Signaling Pathways

The following diagrams visualize key experimental workflows and functional relationships in G-MNP sorbent development.

Diagram 1: G-MNP Sorbent Fabrication Workflow

Diagram 2: Bioinspired Sorbent Mechanism of Action

Troubleshooting and Optimization Guidelines

Common challenges in G-MNP sorbent development and recommended solutions:

- Aggregation of Nanoparticles: Optimize capping agent concentration during synthesis; implement physical dispersion methods (sonication); incorporate stabilizers in composite formulation [19].

- Inconsistent Sorption Performance: Standardize biological source materials; control nanoparticle size distribution through synthesis parameter optimization; ensure uniform functionalization [19] [21].

- Low Selectivity in Complex Matrices: Enhance mimetic analog design; incorporate pre-cleaning steps in extraction protocols; optimize loading conditions (pH, ionic strength) [25] [23].

- Sorbent Degradation During Regeneration: Optimize crosslinking density; implement gentler elution protocols; monitor sorbent integrity through multiple cycles [25].

Green-synthesized metal nanoparticles represent a transformative class of bioinspired materials with significant potential as advanced sorbents in separation science. Their eco-friendly synthesis, biocompatible nature, and tunable surface chemistry make them ideal platforms for developing selective sorption systems, particularly when functionalized with mimetic analogs. The protocols and application notes provided herein establish a framework for standardized research in this emerging field, enabling the development of next-generation sorbents with enhanced selectivity, capacity, and sustainability profiles for pharmaceutical, environmental, and analytical applications.

In the development of advanced bioinorganic sorbents, particularly those employing mimetic analogs, a thorough understanding of the fundamental sorption mechanisms is paramount. These mechanisms—coordination, hydrophobic, and electrostatic interactions—collectively govern the affinity, selectivity, and capacity of sorbents for their target molecules [1]. The strategic application of these principles is exemplified in the preparation of sorbents based on imprinted proteins, where template molecules (mimetic analogs) create specific binding cavities within a protein matrix, such as bovine serum albumin, which is then immobilized on an inorganic support like silicon dioxide [1]. This document details the experimental protocols and analytical methods for investigating these core mechanisms, providing a practical framework for researchers designing selective sorption materials for applications in drug development, environmental monitoring, and analytical chemistry.

Experimental Protocols for Investigating Sorption Mechanisms

Protocol for Batch Sorption Experiments

Objective: To quantify the sorption capacity (Q, mg/g) of a bioinorganic sorbent for a target analyte (e.g., a mycotoxin or pharmaceutical) and determine the underlying sorption mechanism through isotherm and kinetic analysis [1] [26].

Materials:

- Sorbent: Bioinorganic sorbent (e.g., SiO₂ particles modified with an imprinted protein).

- Analyte Solution: Standard solution of the target molecule (e.g., zearalenone, coumarin, diclofenac sodium, venlafaxine) prepared in an appropriate buffer or solvent.

- Equipment: Orbital shaker, centrifuge, analytical instrumentation (e.g., HPLC, HPLC-MS/MS).

Procedure:

- Preparation: Precisely weigh multiple portions of the sorbent (e.g., 10.0 mg) into a series of glass vials.

- Sorption: To each vial, add a fixed volume (e.g., 10.0 mL) of the analyte solution at varying initial concentrations (

C₀). Run experiments in triplicate. - Equilibration: Seal the vials and agitate them on an orbital shaker at a constant temperature (e.g., 25°C) until equilibrium is reached (typically 24 hours, as established by kinetic studies).

- Separation: Centrifuge the vials and carefully separate the supernatant from the solid sorbent.

- Analysis: Quantify the equilibrium concentration (

Cₑ) of the analyte in the supernatant using a calibrated analytical method like HPLC. - Calculation: Calculate the amount of analyte sorbed at equilibrium (

Qₑ, mg/g) using the formula:Qₑ = (C₀ - Cₑ) * V / mwhereVis the solution volume (L), andmis the sorbent mass (g) [26].

Protocol for Isotherm Modeling and Mechanism Elucidation

Objective: To fit experimental sorption data to mathematical models, identifying the dominant sorption mechanism and quantifying sorption capacity.

Procedure:

- Data Compilation: For each initial concentration

C₀, record the calculatedQₑand measuredCₑ. - Model Fitting: Plot

QₑagainstCₑand fit the data to established isotherm models using non-linear regression:- Langmuir Model: Assumes monolayer sorption onto a surface with a finite number of identical sites. The linear form is:

Cₑ / Qₑ = 1 / (Qₘₐₓ * K_L) + Cₑ / QₘₐₓwhereQₘₐₓis the maximum sorption capacity (mg/g) andK_Lis the Langmuir constant (L/mg) related to affinity [26]. - Freundlich Model: An empirical model for heterogeneous surfaces. The linear form is:

log Qₑ = log K_F + (1/n) * log CₑwhereK_Fis the Freundlich constant ((mg/g)/(mg/L)ⁿ) and1/nis the heterogeneity factor.

- Langmuir Model: Assumes monolayer sorption onto a surface with a finite number of identical sites. The linear form is:

- Mechanism Inference: The best-fit model indicates the primary sorption mechanism. A good fit to the Langmuir model suggests specific, monolayer sorption, often driven by coordination or strong electrostatic interactions at defined sites. A good fit to the Freundlich model suggests multilayer sorption on a heterogeneous surface, where hydrophobic interactions are often significant [26].

Table 1: Quantifying Sorption Performance of a Bioinorganic Sorbent for Various Analytes [1]

| Target Analyte | Sorption Capacity, Q (mg/g) | Imprinting Factor (IF) | Primary Interaction Mechanism Inferred |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5,7-Dimethoxycoumarin | 2.2 | Data Not Provided | Hydrophobic, Coordination |

| Coumarin | 2.0 | Data Not Provided | Hydrophobic |

| 4-Hydroxycoumarin | 1.2 | Data Not Provided | Electrostatic, Coordination |

| Quercetin | 0.8 | Data Not Provided | Coordination, Electrostatic |

| Zearalenone (ZEA) | 4.79 | 2.45 | Hydrophobic, Coordination |

Protocol for Spectroscopic and Computational Validation

Objective: To provide molecular-level evidence for the sorption mechanisms proposed by isotherm models.

A. Fourier-Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy:

- Preparation: Analyze the pristine sorbent, the sorbent after analyte loading, and the pure analyte.

- Analysis: Compare the spectra. A shift or change in intensity of functional groups (e.g., -OH, -NH, C=O) on the sorbent after sorption indicates involvement in coordination. The appearance of new peaks or shifts in the analyte's fingerprint region confirms its successful binding [26].

B. X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS):

- Preparation: Analyze the sorbent before and after analyte sorption.

- Analysis: Monitor the binding energies of key elemental peaks (e.g., O 1s, N 1s). A shift in these peaks confirms a change in the chemical environment of these atoms, providing direct evidence for coordination between the sorbent's functional groups and the analyte [26].

C. Density Functional Theory (DFT) Calculations:

- Modeling: Construct molecular models of the sorbent's active site (e.g., the imprinted cavity) and the analyte.

- Simulation: Optimize the geometry of the sorbent-analyte complex and calculate the binding energy.

- Analysis: Analyze the electron density distribution, electrostatic potential maps, and orbital interactions. A strong binding energy and clear electron sharing/donation indicate coordination. Non-covalent interactions and the orientation of the analyte in the cavity can visualize hydrophobic and electrostatic interactions [26].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Bioinorganic Sorbent Research

| Reagent/Material | Function and Application in Research |

|---|---|

| Silicon Dioxide (SiO₂) Particles | Inorganic support matrix; provides a high-surface-area, rigid platform for functionalization with imprinted proteins or other organic phases [1]. |

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) | A model template protein used in the bioimprinting process to create specific molecular recognition cavities for target analytes [1]. |

| Mimetic Analogs | Safe, structurally similar molecules used during the imprinting process to create cavities that selectively bind the target toxin or pharmaceutical [1]. |

| Cross-linking Agents | Chemicals that stabilize the three-dimensional structure of the imprinted protein, locking the binding cavities in place after template removal. |

| High-Performance Liquid Chromatography | Core analytical technique for quantifying analyte concentrations in solution before and after sorption experiments to determine sorption capacity [1]. |

| Molecular Docking Software | Computational tool used to screen and select optimal mimetic analogs by predicting their binding affinity and orientation within the template protein [1]. |

Sorption Mechanism Workflow and Decision Framework

The following diagram illustrates the integrated experimental and computational workflow for developing a mimetic-based sorbent and elucidating its sorption mechanisms.

Sorbent Development and Mechanism Analysis Workflow

A multidisciplinary approach, combining rigorous batch sorption experiments with advanced spectroscopic characterization and computational modeling, is essential for deconvoluting the complex interplay of coordination, hydrophobic, and electrostatic interactions in bioinorganic sorbents. The protocols outlined herein provide a standardized framework for researchers to quantitatively assess these mechanisms, thereby enabling the rational design of highly selective and efficient sorbents using mimetic analogs. This foundational work is critical for advancing applications in sensitive diagnostics, targeted drug delivery, and environmental remediation.

Synthesis and Biomedical Implementation of Mimetic Sorbents

Advanced Fabrication Techniques for MOF-based Sorbents

The transition of metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) from laboratory-scale powders to practical, engineered sorbents represents a critical challenge in materials science. While MOFs possess exceptional intrinsic properties—including surface areas exceeding 7,000 m²/g, tunable pore architectures, and structural diversity—their inherent powdery form presents significant limitations for real-world applications [27]. These limitations include low packing density, handling difficulties, heat and mass transfer inefficiencies, and mechanical instability, which collectively hinder their integration into functional devices and systems [27]. Advanced fabrication techniques that transform MOF powders into structured forms while preserving their functional properties are therefore essential for unlocking their full potential in applications ranging from carbon capture and water harvesting to drug development and clinical analysis.

The pursuit of mimetic analogs in bioinorganic sorbent preparation further amplifies this challenge, requiring fabrication approaches that can replicate the sophisticated functionality of biological systems within engineered materials. This article details the current landscape of MOF shaping methodologies, provides structured comparative data, and presents detailed experimental protocols to guide researchers in selecting and implementing appropriate fabrication strategies for their specific application requirements.

Shaping MOFs into application-oriented forms such as monoliths, pellets, fibers, coatings, and membranes significantly enhances their mechanical stability, ease of handling, and integration potential [27]. The ideal shaping method must achieve multiple objectives: easy processability with enhanced structural rigidity, increased mass loading with reduced transfer resistance, high volumetric sorption capacity with robust durability, and enhanced thermal conductivity for fast regeneration [27]. The selection of an appropriate technique involves careful consideration of trade-offs between mechanical stability, porosity preservation, scalability, and application-specific requirements.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Primary MOF Shaping Techniques

| Shaping Method | Typical Forms | Key Advantages | Key Limitations | Mechanical Stability | Porosity Preservation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Granulation/Pelletization | Pellets, granules | High packing density, excellent handling, scalable | Potential pore blockage, may require binders | High | Moderate to High |

| Extrusion | Monoliths, structured forms | Custom geometries, good mechanical strength | Requires binders/additives, complex setup | Very High | Moderate |

| In-situ Growth | Coatings, membranes | Strong substrate adhesion, uniform layers | Limited to compatible substrates, scalability challenges | Moderate (dependent on substrate) | High |

| Electrospinning | Fibers, mats | High surface-area-to-volume ratio, flexibility | Fiber continuity challenges, parameter sensitivity | Moderate | High |

| 3D Printing | Custom architectures | Design flexibility, complex structures | Resolution limitations, post-processing often needed | Moderate to High | Moderate |

The selection of shaping strategy directly influences critical performance parameters. Monoliths and pellets, typically created through granulation or extrusion, provide high mechanical stability and are ideal for packed-bed applications such as gas storage columns or water harvesting devices [27]. Coatings and membranes, often achieved through in-situ growth or deposition methods, enable efficient mass transfer and are particularly valuable for separation applications and sensor development [27]. More advanced forms such as fibers and 3D-printed structures offer unique benefits for specialized applications including wearable technologies and implantable devices where flexibility and custom geometries are essential.

Detailed Fabrication Protocols

Granulation and Pelletization

Granulation represents one of the most established methods for producing mechanically robust MOF forms suitable for industrial applications. This technique transforms MOF powders into dense, regularly shaped particles that exhibit improved fluid dynamics, reduced pressure drop in flow systems, and enhanced handling properties.

Protocol: Binder-Assisted Granulation of ZIF-8

- Objective: To produce mechanically stable ZIF-8 granules with preserved porosity for sorption applications.

Materials:

- ZIF-8 powder (2.0 g)

- Polyvinyl alcohol (PVA, 5 wt% aqueous solution, 0.4 g solid equivalent)

- Deionized water

- Stainless-steel mold (10 mm diameter)

- Hydraulic press

- Drying oven

- Porosity analyzer (BET surface area measurement)

Procedure:

- Powder Preparation: Pre-dry ZIF-8 powder at 150°C under vacuum for 12 hours to remove adsorbed moisture.

- Binder Integration: Gradually add PVA solution to ZIF-8 powder while mixing in a mortar and pestle. Continue mixing until a homogeneous, damp mixture forms.

- Granule Formation: Transfer the mixture to a sieve with appropriate mesh size (typically 300-500 μm) and apply gentle pressure to extrude nascent granules.

- Compaction: For pellets, load the mixture into a stainless-steel mold and compress at 500-1000 bar for 5 minutes using a hydraulic press.

- Curing: Gradually heat the formed granules/pellets to 120°C over 4 hours and maintain for 12 hours to ensure binder cross-linking.

- Activation: Condition the final products under vacuum at 200°C for 24 hours to remove residual solvents and activate the pore structure.

Quality Control: Evaluate successful fabrication through mechanical testing (crush strength > 2 N per pellet), nitrogen physisorption (BET surface area > 1000 m²/g), and scanning electron microscopy to assess structural integrity.

In-situ Growth on Substrates

In-situ growth enables the direct formation of MOF coatings on various substrates, creating strong interfacial bonds and uniform layers ideal for membrane applications, sensor development, and catalytic systems.

Protocol: UiO-66 Coating on Glass Substrates

- Objective: To deposit a continuous, adherent UiO-66 film on functionalized glass substrates.

Materials:

- Glass substrates (pre-cleaned)

- (3-Aminopropyl)triethoxysilane (APTES, 2% v/v in ethanol)

- Zirconium chloride (ZrCl₄, 0.1 M in DMF)

- 1,4-Benzenedicarboxylic acid (BDC, 0.1 M in DMF)

- N,N-Dimethylformamide (DMF)

- Acetic acid (modulator)

- Solvothermal reactor

Procedure:

- Substrate Functionalization:

- Immerse glass substrates in APTES solution for 2 hours at room temperature.

- Rinse thoroughly with ethanol and cure at 110°C for 1 hour to form amine-terminated surfaces.

- Precursor Solution Preparation:

- Dissolve ZrCl₄ (0.1 M) and BDC (0.1 M) in DMF.

- Add acetic acid (3.5% v/v) as a crystallization modulator.

- Film Growth:

- Place functionalized substrates vertically in the reaction solution.

- Heat at 120°C for 24 hours under static conditions in a sealed solvothermal reactor.

- Post-treatment:

- Carefully remove substrates and rinse with fresh DMF to remove weakly adsorbed crystals.

- Activate by solvent exchange with methanol (3 times over 24 hours) and dry under vacuum at 150°C for 6 hours.

- Substrate Functionalization:

Quality Control: Assess coating quality through optical microscopy (continuity), X-ray diffraction (crystallinity), and nitrogen adsorption (porosity). Adhesion can be tested using standard tape tests.

Composite Integration Strategies

The integration of nanoparticles within MOF matrices creates composite materials with enhanced functionality, particularly valuable for catalytic applications and advanced sensing platforms.

Protocol: "Ship-in-Bottle" Nanoparticle Encapsulation in NU-1000

- Objective: To encapsulate gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) within the pores of NU-1000 for catalytic applications.

Materials:

- Pre-synthesized NU-1000 crystals

- Carboxy-phenylacetylene (PA) linker

- Gold(I) triethylphosphine precursor (Au(I)PEt₃⁺)

- Sodium borohydride (NaBH₄, 0.1 M in ethanol)

- Anhydrous dimethylformamide (DMF)

- Argon atmosphere glovebox

Procedure:

- MOF Functionalization:

- Suspend NU-1000 crystals (500 mg) in PA solution (50 mM in DMF).

- React for 12 hours at 60°C with stirring to coordinate PA to the Zr clusters.

- Metal Precursor Loading:

- Add Au(I)PEt₃⁺ solution (10 mM in DMF) to the functionalized MOF.

- Incubate for 6 hours at room temperature to allow gold precursor coordination to acetylene groups.

- Reduction to Nanoparticles:

- Add excess NaBH₄ solution dropwise with vigorous stirring.

- Continue stirring for 2 hours until color changes from yellow to dark brown, indicating AuNP formation.

- Purification:

- Centrifuge and wash multiple times with DMF and ethanol.

- Dry under vacuum at 100°C for 12 hours.

- MOF Functionalization:

Quality Control: Confirm successful encapsulation through TEM imaging (nanoparticle size and distribution), XPS analysis (oxidation state), and catalytic testing using standard reactions such as 4-nitrophenol reduction [28].

Diagram 1: MOF Sorbent Fabrication Workflow. This flowchart outlines the decision process and key steps for different shaping pathways, highlighting critical stages including binder integration, in-situ growth, and composite formation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of MOF fabrication protocols requires careful selection of materials and reagents tailored to specific application requirements. The following table details essential components for MOF-based sorbent development.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for MOF Sorbent Fabrication

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Fabrication | Application Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metal Precursors | ZrCl₄, Zn(NO₃)₂, Cu(OAc)₂, FeCl₃ | Framework node formation | Determines coordination geometry, stability, and functionality |

| Organic Linkers | 1,4-Benzenedicarboxylic acid (BDC), 2-Methylimidazole, Biphenyl-4,4'-dicarboxylic acid (BPDC) | Framework connector and pore definition | Controls pore size, surface chemistry, and functionality |

| Solvent Systems | DMF, DEF, water, ethanol, methanol | Reaction medium for synthesis | Influences crystallization kinetics and morphology |

| Modulators | Acetic acid, benzoic acid, hydrochloric acid | Controls crystal growth and defect engineering | Regulates crystal size and morphology; creates defects |

| Binding Agents | Polyvinyl alcohol (PVA), methylcellulose, graphene oxide | Enhances mechanical integrity in shaped forms | Must balance mechanical strength with porosity preservation |

| Reducing Agents | Sodium borohydride (NaBH₄), hydrogen gas | Converts metal precursors to nanoparticles in composites | Controls nanoparticle size and distribution within MOF pores |

| Functionalization Agents | APTES, thiol compounds, polyethyleneimine | Imparts specific surface chemistry for enhanced selectivity | Enables covalent attachment to substrates or introduction of specific binding sites |

Advanced Fabrication Strategies for Enhanced Performance

MOF-on-MOF Heterostructures

The creation of hierarchical MOF-on-MOF structures represents a cutting-edge approach to engineering materials with enhanced functionality. This strategy involves the epitaxial growth of one MOF on another, creating core-shell architectures that combine the properties of both frameworks while minimizing detrimental interactions between functional components. Research has demonstrated that MOF-on-MOF heterostructures can significantly improve quantum yields (up to 40.0% compared to 10.2% for multivariate MOFs) by strategically separating fluorophores that would otherwise quench each other's emission when in close proximity [29].

Protocol: UiO-67-based MOF-on-MOF Core-Shell Structure

- Objective: To grow a shell MOF (Zr-AzoBDC or Zr-StilBDC) on pre-formed UiO-67 cores.

- Materials:

- Pre-synthesized UiO-67 crystals (core)

- Shell MOF precursors (appropriate metal salt and organic linker)

- Structure-directing surfactants (e.g., cetyltrimethylammonium bromide)

- Solvothermal reactor

- Procedure:

- Core Activation: Pre-treat UiO-67 cores under vacuum at 150°C for 6 hours.

- Shell Precursor Preparation: Dissolve shell MOF precursors and surfactant in appropriate solvent.

- Heterostructure Growth: Suspend core MOFs in shell precursor solution and conduct solvothermal treatment at optimized temperature and time.

- Purification: Centrifuge and wash thoroughly to remove unreacted precursors.

- Applications: Enhanced luminescence materials, cascade catalysis, and selective separation systems [29].

Green and Scalable Fabrication Approaches

As MOF technologies advance toward commercial application, environmentally benign and scalable fabrication methods become increasingly important. Recent advances have demonstrated promising approaches including mechanochemical synthesis (solvent-free grinding), continuous-flow reactors, and supercritical fluid processing [30]. These methods reduce or eliminate hazardous solvent use while enabling higher production throughput and improved consistency compared to traditional batch solvothermal methods.

Diagram 2: MOF Shaping Method-Performance Relationship Map. This diagram visualizes how different shaping approaches influence critical performance parameters, highlighting the inherent trade-offs in sorbent design.