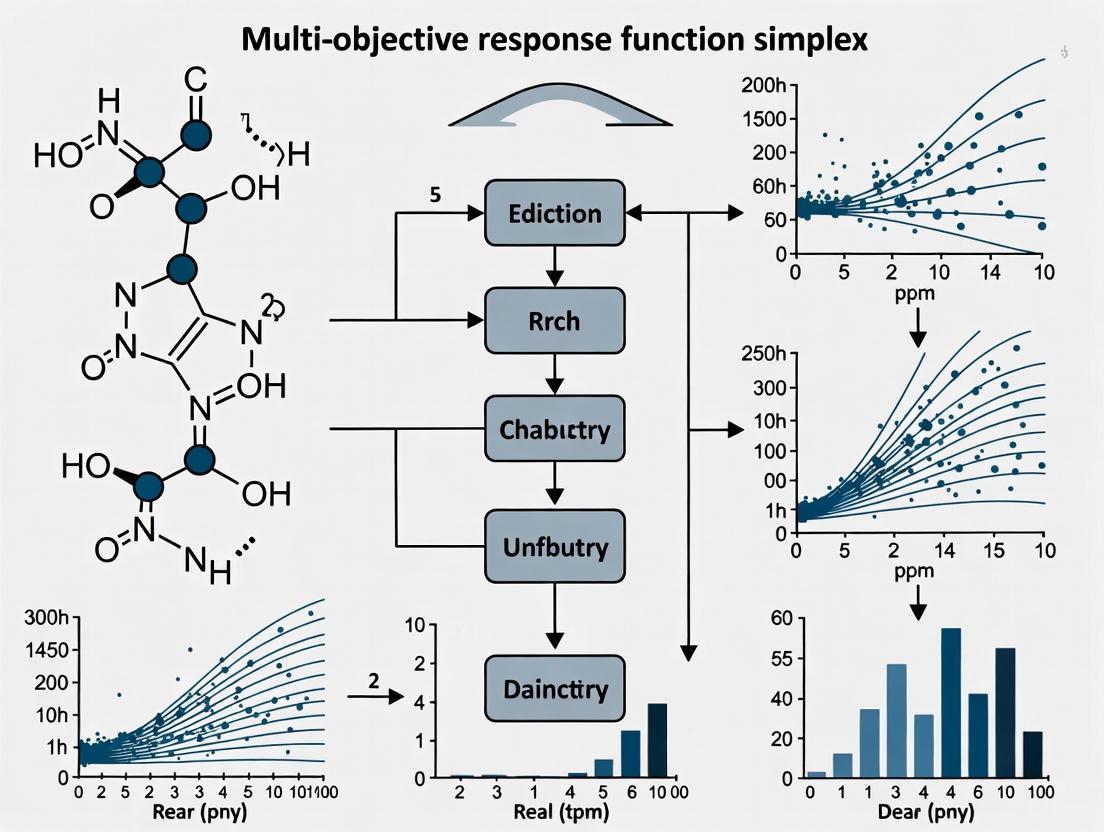

Multi-Objective Response Function Simplex: A Computational Framework for Efficient Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of the Simplex-based framework for multi-objective optimization, with a focused application on response functions in drug discovery.

Multi-Objective Response Function Simplex: A Computational Framework for Efficient Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of the Simplex-based framework for multi-objective optimization, with a focused application on response functions in drug discovery. It covers foundational principles, from the mathematical basis of Multi-Objective Linear Programming (MOLP) solved via the Simplex method to advanced hybrid and surrogate-assisted models. The content details practical methodologies for implementing these techniques to balance conflicting objectives in molecular optimization, such as efficacy, toxicity, and solubility. It further addresses common computational challenges and offers troubleshooting strategies, supported by a comparative analysis of the framework's performance against other state-of-the-art algorithms. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes cutting-edge research to demonstrate how Simplex-based optimization can enhance efficiency and success rates in the design of novel therapeutic compounds.

Core Principles: From Single-Objective Simplex to Multi-Objective Problem Solving

The simplex algorithm, developed by George Dantzig in 1947, represents one of the most significant advancements in mathematical optimization and remains a fundamental technique for solving linear programming problems [1] [2]. This method provides a systematic approach for traversing the vertices of a feasible region polyhedron to find the optimal solution to linear programming problems by iteratively improving the objective function value [3]. The algorithm's name derives from the concept of a simplex, suggested by T. S. Motzkin, though it actually operates on simplicial cones that become proper simplices with an additional constraint [1].

Dantzig's pioneering work emerged from his efforts to mechanize planning processes for the US Army Air Force during World War II, when he realized that most military "ground rules" could be translated into a linear objective function requiring maximization [1]. His key insight was recognizing that one of the unsolved problems from his professor Jerzy Neyman's class—which Dantzig had mistaken as homework—was applicable to finding an algorithm for linear programs [1]. This evolutionary development over approximately one year revolutionized optimization techniques and continues to underpin modern optimization approaches, including multi-objective response function research in pharmaceutical development.

In the context of multi-objective response function simplex research, the simplex algorithm provides the mathematical foundation for navigating complex parameter spaces to identify optimal experimental conditions, particularly valuable in drug development where multiple competing objectives must be balanced simultaneously [4].

Theoretical Foundation

Problem Formulation

The simplex algorithm operates on linear programs in the canonical form:

- Maximize $c^Tx$

- Subject to $Ax ≤ b$ and $x ≥ 0$

where $c = (c₁, …, cₙ)$ represents the coefficients of the objective function, $x = (x₁, …, xₙ)$ represents the decision variables, $A$ is a constraint coefficient matrix, and $b = (b₁, …, bₚ)$ represents the constraint bounds [1].

The algorithm exploits key geometrical properties of linear programming problems. The feasible region defined by all values of $x$ satisfying $Ax ≤ b$ and $xᵢ ≥ 0$ forms a convex polytope [1]. Crucially, if the objective function has a maximum value on the feasible region, then it attains this value at least one of the extreme points (vertices) of this polytope [1]. Furthermore, if an extreme point is not optimal, there exists an edge containing that point along which the objective function increases, guiding the algorithm toward better solutions [5].

Table 1: Linear Programming Standard Form Components

| Component | Description | Role in Algorithm |

|---|---|---|

| Objective Function | $c^Tx$: Linear function to maximize or minimize | Determines direction of optimization |

| Decision Variables | $x = (x₁, …, xₙ)$: Quantities to be determined | Solution components adjusted iteratively |

| Constraints | $Ax ≤ b$: Linear inequalities defining feasible region | Forms polytope boundary for solution space |

| Non-negativity Constraints | $x ≥ 0$: Lower bounds on variables | Ensures practical, implementable solutions |

Standard Form Transformation

To apply the simplex method, problems must first be transformed into standard form through three key operations [1]:

Handling lower bounds: For variables with lower bounds other than zero, new variables are introduced representing the difference between the variable and its bound. For example, given $x₁ ≥ 5$, a new variable $y₁ = x₁ - 5$ is introduced with $y₁ ≥ 0$, then $x₁$ is eliminated by substitution.

Inequality conversion: For each remaining inequality constraint, slack variables are introduced to convert inequalities to equalities. For $x₂ + 2x₃ ≤ 3$, we write $x₂ + 2x₃ + s₁ = 3$ with $s₁ ≥ 0$. For constraints with ≥, surplus variables are subtracted.

Unrestricted variables: Each unrestricted variable is replaced by the difference of two restricted variables. If $z₁$ is unrestricted, we set $z₁ = z₁⁺ - z₁⁻$ with $z₁⁺, z₁⁻ ≥ 0$.

After transformation, the feasible region is expressed as $Ax = b$ with $xᵢ ≥ 0$ for all variables, and we assume the rank of $A$ equals the number of rows, ensuring no redundant constraints [1].

Computational Methodology

Simplex Tableau and Pivot Operations

The simplex algorithm utilizes a tableau representation to organize computations systematically. A linear program in standard form can be represented as:

The first row defines the objective function, while remaining rows specify constraints [1]. Through a series of row operations, this tableau can be transformed into canonical form relative to a specific basis:

Here, $z_B$ represents the objective function value at the current basic feasible solution, and the relative cost coefficients $c̄𝐷ᵀ$ indicate the rate of change of the objective function with respect to nonbasic variables [1].

The geometrical operation of moving between adjacent basic feasible solutions is implemented computationally through pivot operations [1]. Each pivot involves:

- Selecting a nonzero pivot element in a nonbasic column

- Multiplying the pivot row by its reciprocal to convert the pivot element to 1

- Adding multiples of the pivot row to other rows to eliminate other entries in the pivot column

- Converting the pivot column to correspond to an identity matrix column

This process effectively exchanges a basic and nonbasic variable, moving the solution to an adjacent vertex of the polytope [1].

Algorithmic Steps

The simplex method follows a systematic procedure [2]:

- Set up the problem: Write the objective function and inequality constraints.

- Convert inequalities to equations: Introduce slack variables for each inequality.

- Construct initial simplex tableau: Write the objective function as the bottom row.

- Identify pivot column: Select the most negative entry in the bottom row (for maximization).

- Calculate quotients: Divide the far right column by the pivot column entries; select the row with the smallest nonnegative quotient.

- Perform pivoting: Make the pivot element 1 and all other elements in the pivot column 0.

- Check optimality: If no negative entries remain in the bottom row, the solution is optimal; otherwise return to step 4.

- Interpret results: Read solution variables from columns with 1 and 0s; all other variables are zero.

Simplex Algorithm Workflow: The systematic process for solving linear programming problems using the simplex method, illustrating the iterative nature of pivot operations and optimality checking.

Application in Multi-Objective Response Function Research

Hybrid Experimental Simplex Algorithm (HESA)

The Hybrid Experimental Simplex Algorithm (HESA) represents an advanced adaptation of the classical simplex method specifically designed for identifying "sweet spots" in experimental domains, particularly valuable in bioprocess development [4]. HESA extends the established simplex method to efficiently locate subsets of experimental conditions necessary for identifying operating envelopes, making it especially suitable for coarsely gridded data commonly encountered in pharmaceutical research.

In comparative studies with conventional Design of Experiments (DoE) methodologies, HESA has demonstrated superior capability in delivering valuable information regarding the size, shape, and location of operating "sweet spots" that can be further investigated and optimized in subsequent studies [4]. Notably, HESA achieves this with comparable experimental costs to traditional DoE methods, establishing it as a viable and valuable alternative for scouting studies in bioprocess development.

Feature-Based Optimization in Microwave and Antenna Design

Recent advancements have demonstrated the application of simplex-based methodologies for globalized optimization of complex systems through operating parameter handling. This approach reformulates optimization problems in terms of system operating parameters (e.g., center frequencies, power split ratios) rather than complete response characteristics, significantly regularizing the objective function landscape [6] [7].

The methodology employs simplex-based regression models constructed using low-fidelity simulations, enabling efficient global exploration of the parameter space [7]. This global search is complemented by local gradient-based tuning utilizing high-fidelity models, with sensitivity updates restricted to principal directions to reduce computational expense without sacrificing solution quality [7].

Table 2: Simplex Algorithm Variants for Multi-Objective Optimization

| Algorithm Variant | Key Features | Application Context | Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Classical Simplex | Vertex-to-vertex traversal, pivot operations | General linear programming problems | Guaranteed convergence, systematic approach |

| HESA | Adapted for coarsely gridded data, sweet spot identification | Bioprocess development, scouting studies | Better defines operating boundaries vs. traditional DoE |

| Simplex Surrogates | Regression models, operating parameter space exploration | Microwave/antenna design, computational models | Global search capability, reduced computational cost |

| Dual-Resolution Methods | Variable-fidelity models, restricted sensitivity updates | EM-driven design, expensive function evaluations | Remarkable computational efficiency (≤80 high-fidelity simulations) |

Experimental Protocols and Implementation

Protocol: Standard Simplex Method Implementation

Purpose: To solve linear programming maximization problems using the simplex method [2].

Materials and Computational Resources:

- Linear programming problem in standard form

- Matrix manipulation software (Python NumPy, MATLAB, or equivalent)

- Simplex tableau implementation framework

Procedure:

- Problem Formulation:

- Express the objective function as $c^Tx$ to be maximized

- Formulate all constraints in the form $Ax ≤ b$ with $x ≥ 0$

Standard Form Conversion:

- Introduce slack variables for each inequality constraint

- For each constraint $aᵢ₁x₁ + ... + aᵢₙxₙ ≤ bᵢ$, add slack variable $sᵢ ≥ 0$ to create equality

- Express the objective function in terms of all variables (decision and slack)

Initial Tableau Construction:

- Create the augmented matrix combining constraint coefficients and constants

- Add the objective function row with negated coefficients

- Format as:

[1, -cᵀ, 0; 0, A, b]

Iteration Phase:

- Pivot Column Selection: Identify the most negative entry in the objective function row

- Pivot Row Selection: For each row, compute θ = bᵢ/aᵢₖ (where aᵢₖ > 0); select row with minimal θ

- Pivot Operation:

- Normalize the pivot row by dividing by the pivot element

- For all other rows, including the objective row: subtract appropriate multiple of pivot row to zero out the pivot column

- Repeat until no negative entries remain in the objective function row

Solution Extraction:

- Identify columns that form an identity matrix

- Variables corresponding to identity columns equal the corresponding b values

- All other variables equal zero

- Optimal objective value appears in the upper-right corner of the tableau

Validation:

- Verify all constraints are satisfied

- Confirm no further improvement possible by checking reduced costs (objective row coefficients)

- Validate solution feasibility ($x ≥ 0$)

Protocol: Hybrid Experimental Simplex Algorithm (HESA)

Purpose: To identify operational "sweet spots" in experimental domains using augmented simplex methodology [4].

Materials:

- Experimental system with multiple input variables and response outputs

- Laboratory equipment for high-throughput experimentation (e.g., 96-well filter plate format)

- Response measurement instrumentation

Procedure:

- Experimental Domain Definition:

- Identify critical process parameters (CPPs) and their feasible ranges

- Define quality target product profile (QTPP) and critical quality attributes (CQAs)

- Establish experimental constraints based on prior knowledge

Initial Experimental Design:

- Select sparse, space-filling design across the parameter space

- Execute experiments in randomized order to minimize bias

- Measure all relevant responses for each experimental condition

Simplex Progression:

- Construct initial simplex in parameter space using most promising experimental results

- Implement modified simplex rules to navigate toward optimal regions

- Incorporate reflection, expansion, and contraction operations adapted for experimental variability

Response Surface Mapping:

- Iteratively refine experimental focus toward promising regions

- Balance exploration of new regions with exploitation of known good regions

- Continue until satisfactory operational envelope is identified

Verification and Validation:

- Confirm sweet spot boundaries with additional experiments

- Validate operational robustness within identified regions

- Compare results with conventional DoE approaches if applicable

HESA Methodology: The Hybrid Experimental Simplex Algorithm process for identifying operational sweet spots in experimental domains, showing the iterative nature of experimental design and refinement.

Research Reagent Solutions and Computational Tools

Table 3: Essential Research Materials and Computational Tools for Simplex Algorithm Implementation

| Category | Specific Tool/Resource | Function/Purpose | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Computational Frameworks | MATLAB Optimization Toolbox | Matrix operations, tableau implementation | General linear programming problems |

| Python SciPy/NumPy | Algorithm implementation, numerical computations | Custom simplex implementation | |

| Commercial Solvers (Gurobi, CPLEX) | Large-scale problem solving | Industrial-scale optimization | |

| Experimental Platforms | 96-well filter plate systems | High-throughput experimentation | HESA implementation in bioprocessing |

| Automated liquid handling systems | Precise reagent dispensing | Experimental reproducibility | |

| Multi-parameter analytical instruments | Response measurement | Quality attribute quantification | |

| Specialized Methodologies | Dual-fidelity EM simulations | Variable-resolution modeling | Microwave/antenna optimization [6] [7] |

| Principal direction sensitivity analysis | Restricted gradient computation | Computational efficiency in tuning | |

| Simplex-based regression surrogates | Operating parameter prediction | Global design optimization |

Advanced Applications and Future Directions

The simplex algorithm continues to evolve beyond its traditional linear programming domain, finding novel applications in complex optimization scenarios. Modern implementations have demonstrated remarkable efficiency in globalized parameter tuning, with applications in microwave and antenna design requiring fewer than eighty high-fidelity simulations on average to identify optimal designs [7]. This represents a significant advancement over conventional approaches, particularly nature-inspired metaheuristics that typically require thousands of objective function evaluations.

In pharmaceutical contexts, simplex-based methodologies enable efficient exploration of complex experimental spaces where multiple objectives must be balanced, such as binding efficiency, purity, yield, and cost [4]. The ability to identify operational sweet spots with comparable experimental costs to traditional DoE methods while providing better definition of operating boundaries positions simplex variants as valuable tools for bioprocess development.

Future research directions include increased integration of simplex methodologies with machine learning approaches, enhanced handling of stochastic systems, and development of hybrid techniques combining the systematic approach of simplex with global exploration capabilities of population-based methods. These advancements will further solidify the role of simplex-based algorithms in multi-objective response function research across scientific and engineering disciplines.

Defining Multi-Objective Optimization Problems (MOPs) in Science

In scientific and engineering disciplines, decision-making often requires balancing several competing criteria. Multi-Objective Optimization Problems (MOPs) are mathematical frameworks concerned with optimizing more than one objective function simultaneously [8]. Applications are diverse, ranging from minimizing cost while maximizing comfort in product design, to maximizing drug potency while minimizing side effects and synthesis costs in pharmaceutical development [8] [9]. The fundamental challenge of MOPs is that objectives typically conflict; no single solution exists that optimizes all objectives at once. Instead, solvers seek a set of trade-off solutions known as the Pareto front [8] [9]. A solution is considered Pareto optimal, or non-dominated, if no objective can be improved without worsening at least one other objective [8]. This makes the Pareto front the set of all potentially optimal compromises from which a decision-maker can choose.

Table 1: Key Terminology in Multi-Objective Optimization

| Term | Mathematical/Symbolic Definition | Explanation | |

|---|---|---|---|

| MOP Formulation | min_x (f₁(x), f₂(x), ..., f_k(x)) where x ∈ X [8] |

Finding the vector x of decision variables that minimizes a vector of k objective functions. |

|

| Pareto Dominance | For two solutions x₁ and x₂, x₁ dominates x₂ if:1. ∀i: f_i(x₁) ≤ f_i(x₂)2. ∃j: f_j(x₁) < f_j(x₂) [8] [9] |

Solution x₁ is at least as good as x₂ in all objectives and strictly better in at least one. |

|

| Pareto Optimal Set | `X* = {x ∈ X | ¬∃ x' ∈ X: x' dominates x}` [8] | The set of all decision vectors that are not dominated by any other feasible vector. |

| Pareto Front | { (f₁(x), f₂(x), ..., f_k(x)) | x ∈ X* } [8] |

The image of the Pareto optimal set in the objective space, representing the set of optimal trade-offs. | |

| Ideal Objective Vector | z^ideal = (inf f₁(x*), ..., inf f_k(x*)) for x* ∈ X* [8] |

A vector containing the best achievable value for each objective, often unattainable. |

Diagram 1: The mapping from the decision space to the objective space, showing the relationship between feasible solutions, the Pareto optimal set, and the Pareto front. The ideal and nadir vectors bound the front.

Mathematical Frameworks and Solution Methodologies

Solving MOPs requires specialized methodologies to handle the partial order induced by multiple objectives. Solution approaches can be broadly categorized into a priori, a posteriori, and interactive methods, depending on when the decision-maker provides preference information [9]. A posteriori methods, which first approximate the entire Pareto front before decision-making, are common and enable a thorough exploration of trade-offs. Core to these methods are scalarization techniques, which transform a MOP into a set of single-objective problems. The two primary scalarization methods are the Weighted Sum method and the ε-Constraint method [10] [11].

Table 2: Comparison of Primary MOP Scalarization Methods

| Method | Mathematical Formulation | Key Parameters | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weighted Sum | min Σ (wₘ * fₘ(x)) where Σ wₘ = 1 [10] [11] |

Weight factors wₘ for each objective m. |

Simple, intuitive, uses standard SOO solvers. | Cannot find Pareto-optimal solutions on non-convex parts of the front [11]. Requires objective scaling [11]. |

| ε-Constraint | min fᵢ(x) subject to fₘ(x) ≤ εₘ for all m ≠ i [10] |

Upper bounds εₘ for all but one objective. |

Can find solutions on non-convex fronts. Provides direct control over objective bounds [11]. | Requires appropriate selection of ε values, which can be challenging [10]. |

For problems with complex, non-linear, or computationally expensive models (e.g., those relying on finite-element simulation or wet-lab experiments), evolutionary algorithms and other metaheuristics are highly effective. Algorithms such as the Non-dominated Sorting Genetic Algorithm II (NSGA-II) and the Strength Pareto Evolutionary Algorithm 2 (SPEA2) use a population-based approach to approximate the Pareto front in a single run [9]. Furthermore, surrogate modeling is often employed to reduce computational cost by replacing expensive function evaluations with approximate, data-driven models [12] [13].

Application Protocol: Bioprocess Development using the Desirability Approach and Simplex Optimization

This protocol details an a posteriori method for multi-objective optimization in early-stage bioprocess development, specifically for purifying biological products using chromatography. It integrates the Desirability Approach for objective aggregation with a Grid-Compatible Simplex algorithm for efficient experimental navigation [12].

Background and Principle

In high-throughput (HT) bioprocess development, scientists must rapidly identify optimal operating conditions that balance multiple, conflicting product quality and yield objectives. The desirability function (d_k) scales individual responses (e.g., yield, impurity levels) to a [0, 1] interval, where 1 is most desirable. The overall, multi-objective performance is then measured by the total desirability (D), which is the geometric mean of the individual desirabilities [12]. This approach guarantees that the optimum found is a member of the Pareto set [12]. The Simplex algorithm efficiently guides the experimental search for high-desirability conditions within a pre-defined grid of possible experiments.

Reagents and Equipment

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

| Item Name | Function/Description | Example/Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Chromatography Resin | Stationary phase for separating the target product from impurities. | Example: Anion-exchange resin. |

| Elution Buffers | Mobile phase used to displace bound molecules from the resin. | Varying pH and salt concentration as design factors. |

| Host Cell Protein (HCP) Assay Kit | Quantifies residual HCP, a key impurity to be minimized. | ELISA-based kit. |

| Residual DNA Assay Kit | Quantifies residual host cell DNA, an impurity to be minimized. | Fluorometric or qPCR-based kit. |

| Product Concentration Assay | Quantifies the yield of the target biological product. | HPLC, UV-Vis, or activity assay. |

| High-Throughput Screening System | Automated platform for preparing and testing many experimental conditions. | Robotic liquid handler and microplate reader. |

Step-by-Step Procedure

Problem Formulation and Experimental Grid Setup:

- Define Objectives: Identify 3 key responses:

y₁ = Product Yield(to be maximized),y₂ = Host Cell Protein (HCP)(to be minimized), andy₃ = Residual DNA(to be minimized). - Define Factors: Select the input variables to be optimized (e.g.,

Factor A: Elution pH,Factor B: Salt Concentration). - Define Grid: Create a discrete grid of factor level combinations to be tested. Assign monotonically increasing integers to each factor level [12].

- Define Objectives: Identify 3 key responses:

Configure Desirability Functions:

- For each response, define the desirability function parameters based on product quality requirements and regulatory guidelines [12]:

- For Yield (

y₁, maximize): Set a lower limitL₁(e.g., 0%) and a targetT₁(e.g., 100%). - For HCP (

y₂, minimize): Set a targetT₂(e.g., detection limit) and an upper limitU₂(e.g., regulatory acceptable level). - For DNA (

y₃, minimize): Set a targetT₃and an upper limitU₃.

- For Yield (

- Optional but recommended for decision-making: Instead of pre-defining fixed weights (

w_k), include them as inputs in the optimization problem to explore the impact of different weightings on the final solution [12].

- For each response, define the desirability function parameters based on product quality requirements and regulatory guidelines [12]:

Execute Grid-Compatible Simplex Optimization:

- Preprocessing: The search space is preprocessed, and any missing data points in the grid are replaced with highly unfavorable surrogate values [12].

- Initial Simplex: Define a starting point or initial simplex within the experimental grid.

- Iterative Search:

- The conditions defined by the vertices of the current simplex are evaluated (or their pre-run data is retrieved).

- The total desirability

Dis calculated for each vertex. - Based on a deterministic update strategy, the algorithm suggests a new test condition (a new vertex) to evaluate.

- This process repeats, with the simplex moving away from unfavorable areas and focusing on promising conditions.

- Termination: The algorithm terminates when it can no longer find a new vertex that improves the total desirability, indicating a local optimum has been found [12].

Validation and Analysis:

- The optimal conditions identified by the Simplex search are validated.

- Analyze the results to understand the trade-offs between yield and impurity clearance. The solution provided will be a Pareto-optimal point.

Diagram 2: Experimental workflow for multi-objective optimization using the desirability approach and the grid-compatible Simplex algorithm.

Advanced Applications and Considerations

The principles of MOPs extend to numerous scientific fields. In antenna design, engineers face trade-offs between bandwidth, gain, physical size, and efficiency. Modern approaches use multi-resolution electromagnetic simulations, where initial global searches are performed with fast, low-fidelity models, followed by local tuning with high-fidelity models for final verification [13]. In drug discovery, MOPs formally structure the search for compounds that maximize therapeutic potency while minimizing toxicity (side effects) and synthesis costs [9]. A key challenge in these domains is the computational expense of evaluations, driving the development of surrogate-assisted and evolutionary algorithms.

When deploying these methodologies, researchers must consider several factors. The choice between a priori, a posteriori, and interactive methods depends on the decision-making context and the availability of preference information [9]. For algorithms, the No Free Lunch theorem implies that no single optimizer is best for all problems; the choice must be fit-for-purpose. Finally, rigorous statistical assessment of results, especially when using stochastic optimizers like evolutionary algorithms, is crucial for drawing meaningful scientific conclusions [9].

The Challenge of Conflicting Objectives in Drug Molecule Design

The discovery and development of new therapeutic agents inherently involve balancing multiple, often competing, objectives. The traditional "one drug, one target" paradigm is increasingly giving way to a more holistic approach, rational polypharmacology, which aims to design drugs that intentionally interact with multiple specific molecular targets to achieve synergistic therapeutic effects for complex diseases [14]. This shift acknowledges that diseases like cancer, neurodegenerative disorders, and metabolic syndromes involve dysregulation of multiple genes, proteins, and pathways [14]. However, this approach introduces significant design challenges, as optimizing for one property (e.g., potency against a primary target) can negatively impact others (e.g., selectivity, solubility, or metabolic stability) [14]. Navigating this complex optimization landscape requires sophisticated strategies that can simultaneously balance numerous, conflicting objectives to identify candidate molecules with the best overall profile.

Theoretical Framework: Multi-Objective Response Functions and Desirability

The Desirability Approach for Response Amalgamation

A powerful methodology for handling multiple objectives is the desirability function approach, which provides a mathematical framework for combining multiple responses into a single, composite objective function [12]. In this approach, individual responses (e.g., yield, purity, potency) are transformed into individual desirability values (d_k) that range from 0 (completely undesirable) to 1 (fully desirable) [12].

The transformation differs based on whether a response needs to be maximized or minimized. For responses to be maximized (Equation 1), the function increases linearly or non-linearly from a lower limit (Lk) to a target value (Tk). For responses to be minimized (Equation 2), the function decreases from an upper limit (Uk) to the target (Tk) [12]. The shape of these functions is controlled by weights (w_k), which determine the relative importance of reaching the target value [12].

The overall, composite desirability (D) is then calculated as the geometric mean of the individual desirabilities (Equation 3) [12]. This composite value serves as the single objective function for optimization, with values closer to 1 representing more favorable overall performance across all considered responses.

Key Advantages of the Desirability Framework

- Pareto Optimal Solutions: The desirability approach yields solutions that belong to the Pareto set, meaning no single objective can be improved without worsening at least one other objective [12]. This prevents the selection of solutions that are inferior to alternatives across all responses.

- Explicit Weight Specification: By requiring explicit definition of weights for each response, the method forces deliberate consideration of the relative importance of each objective [12].

- Constraint Incorporation: The lower and upper limits (Lk and Uk) effectively function as performance constraints on individual responses, defining the admissible region of operation [12].

Table 1: Parameters for the Desirability Function Approach

| Parameter | Symbol | Description | Considerations for Drug Design |

|---|---|---|---|

| Target Value | T_k | Ideal value for response k | Based on therapeutic requirements (e.g., IC50 < 100 nM) |

| Lower Limit | L_k | Minimum acceptable value for responses to be maximized | Defined by minimal efficacy or quality thresholds |

| Upper Limit | U_k | Maximum acceptable value for responses to be minimized | Determined by toxicity or safety limits |

| Weight | w_k | Relative importance of reaching T_k | Expert-driven; determines optimization priority |

Experimental Protocol: Simplex Optimization with Multi-Objective Desirability

Grid-Compatible Simplex Method

The grid-compatible Simplex algorithm is an empirical, self-directing optimization strategy particularly suited for challenging early development investigations with limited data [12]. This method efficiently navigates the experimental space by iteratively moving away from unfavorable conditions and focusing on more promising regions until an optimum is identified [12]. Unlike traditional design of experiments (DoE) approaches that require extensive upfront modeling, the Simplex method operates through real-time experimental evaluation and suggestion of new test conditions [12].

Protocol: Deployment of Grid-Compatible Simplex for Multi-Objective Drug Design Optimization

Preprocessing of Search Space

- Assign monotonically increasing integers to the levels of each experimental factor (e.g., pH, temperature, concentration ratios)

- Replace any missing data points with highly unfavorable surrogate values to ensure algorithm functionality [12]

- Define the boundaries of the experimental domain based on practical constraints

Definition of Starting Conditions

Iterative Optimization Loop

- Suggest new test conditions for evaluation based on previous results

- Convert obtained responses into new test conditions using Simplex operations (reflection, expansion, contraction) [12]

- Calculate the composite desirability (D) for each experimental condition using Equations 1-3

- Continue iteration until convergence criteria are met (e.g., no significant improvement in D after multiple steps)

Verification and Validation

- Confirm optimal conditions through replicate experiments

- Validate model predictions across the optimal region [12]

Workflow Visualization

Diagram 1: Simplex Optimization Workflow. This diagram illustrates the iterative process of the grid-compatible Simplex method for multi-objective optimization.

Advanced Integration: Machine Learning with Active Learning Cycles

Generative AI with Nested Active Learning

Recent advances integrate generative models with active learning frameworks to address the limitations of traditional optimization in exploring vast chemical spaces [15]. These systems employ a structured pipeline where a variational autoencoder (VAE) is combined with nested active learning cycles to iteratively refine molecular generation toward desired multi-objective profiles [15].

Protocol: Generative AI with Active Learning for Multi-Objective Drug Design

Data Representation and Initial Training

Inner Active Learning Cycle (Chemical Optimization)

- Sample the VAE to generate new molecules

- Evaluate generated molecules for drug-likeness, synthetic accessibility, and similarity to training set using chemoinformatic predictors [15]

- Transfer molecules meeting threshold criteria to a temporal-specific set

- Use this set to fine-tune the VAE, prioritizing molecules with desired properties [15]

Outer Active Learning Cycle (Affinity Optimization)

Candidate Selection and Validation

- Apply stringent filtration processes to identify promising candidates

- Utilize intensive molecular modeling simulations (e.g., PELE) for in-depth evaluation of binding interactions [15]

- Select top candidates for synthesis and experimental validation

Integrated Workflow Visualization

Diagram 2: Generative AI with Nested Active Learning. This diagram shows the integrated workflow combining generative models with nested active learning cycles for multi-objective molecular optimization.

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Multi-Objective Drug Optimization

| Category | Specific Tool/Resource | Function in Multi-Objective Optimization | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Databases | ChEMBL | Provides bioactivity data for QSAR modeling and training set construction | Target engagement prediction, baseline activity assessment [14] |

| DrugBank | Comprehensive drug-target interaction data for polypharmacology assessment | Multi-target profiling, off-target effect prediction [14] | |

| TTD (Therapeutic Target Database) | Information on known therapeutic targets and associated drugs | Target selection, pathway analysis for complex diseases [14] | |

| Molecular Descriptors | ECFP Fingerprints | Circular fingerprints for molecular similarity and machine learning features | Chemical space navigation, similarity assessment [14] |

| Molecular Graph Representations | Graph-based encodings preserving structural topology | GNN-based multi-target prediction [14] | |

| Protein Structure Resources | PDB (Protein Data Bank) | Experimentally determined 3D structures for molecular docking | Structure-based design, binding site analysis [14] |

| Computational Oracles | Molecular Docking Programs | Physics-based binding affinity prediction | Primary optimization objective, target engagement [15] |

| Synthetic Accessibility Predictors | Estimation of synthetic feasibility | Constraint optimization, practical compound prioritization [15] | |

| Optimization Frameworks | Grid-Compatible Simplex Algorithm | Empirical optimization of multiple responses via desirability functions | Experimental parameter optimization in early development [12] |

| Variational Autoencoders (VAE) | Deep learning architecture for molecular generation with structured latent space | Chemical space exploration, novel scaffold generation [15] |

Case Studies and Applications

Application to Chromatography Process Development

In high-throughput chromatography case studies, the grid-compatible Simplex method successfully optimized three responses simultaneously: yield, residual host cell DNA content, and host cell protein content [12]. These responses exhibited strong nonlinear effects within the studied experimental spaces, making them challenging for traditional DoE approaches [12]. By applying the desirability approach with the Simplex method, researchers rapidly identified operating conditions that offered superior and balanced performance across all outputs compared to alternatives [12]. The method demonstrated relative independence from starting conditions and required sub-minute computations despite its higher-order mathematical functionality compared to DoE techniques [12].

Application to Kinase Inhibitor Design

In a recent application of the integrated generative AI with active learning framework, researchers targeted CDK2 and KRAS - two challenging oncology targets with different chemical space characteristics [15]. For CDK2, which has a densely populated patent space, the workflow successfully generated diverse, drug-like molecules with excellent docking scores and predicted synthetic accessibility [15]. From 10 selected molecules synthesized, 8 showed in vitro activity against CDK2, with one compound reaching nanomolar potency [15]. For KRAS, a target with sparsely populated chemical space, the approach identified 4 molecules with predicted activity, demonstrating the method's effectiveness across different target landscapes [15].

The challenge of conflicting objectives in drug molecule design represents a fundamental complexity in modern therapeutic development. By employing multi-objective optimization frameworks - particularly the desirability function approach combined with Simplex methods and emerging machine learning techniques - researchers can systematically navigate these trade-offs to identify optimal compromise solutions. The protocols and methodologies outlined here provide a structured approach for integrating multiple, often competing objectives into a unified optimization strategy, ultimately accelerating the discovery of effective therapeutic agents with balanced property profiles. As these computational approaches continue to evolve and integrate with experimental validation, they promise to significantly enhance our ability to design sophisticated multi-target therapeutics for complex diseases.

Foundational Simplex Techniques for Multi-Objective Linear Fractional Programming (MOLFP)

Multi-Objective Linear Fractional Programming (FIMOLFP) represents a significant challenge in optimization theory, particularly relevant to pharmaceutical and bioprocess development where goals frequently manifest as ratios of two different objectives, such as cost-effectiveness or efficiency ratios [16]. In real-world scenarios such as financial decision-making and production planning, objectives can often be better expressed as a ratio of two linear functions rather than single linear objectives [16]. The fundamental MOLFP problem can be formulated with multiple objective functions, each being a linear fractional function, where the goal is to find solutions that simultaneously optimize all objectives within a feasible region defined by linear constraints [17].

The simplex algorithm, originally developed by George Dantzig for single-objective linear programming, provides a systematic approach to traverse the vertices of the polyhedron containing feasible solutions [1] [3]. In mathematical terms, a MOLFP problem can be formulated as follows [17]:

- Maximize ( z1 = \frac{c1x + \alpha1}{d1x + \beta1}, z2 = \frac{c2x + \alpha2}{d2x + \beta2}, \ldots, zp = \frac{cpx + \alphap}{dpx + \beta_p} )

- Subject to: ( x \in S = {x \in R^n | Ax \leq b, x \geq 0}, b \in R^m )

- where ( ck, dk \in R^n, A \in R^{m \times n} ) and ( \alphak, \betak \in R ), for ( k = 1, \ldots, p ) and ( \forall k, x \in S: dkx + \betak > 0 )

A key characteristic of MOLFP problems is that there typically does not exist a single solution that simultaneously optimizes all objective functions [8]. Instead, attention focuses on Pareto optimal solutions – solutions that cannot be improved in any objective without degrading at least one other objective [8]. The set of all Pareto optimal solutions constitutes the Pareto front, which represents the trade-offs between conflicting objectives that decision-makers must evaluate [8].

Table 1: Comparison of Multi-Objective Optimization Problem Types

| Problem Type | Mathematical Form | Solution Approach | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| MOLFP | Multiple ratios of linear functions | Weighted sum, desirability, simplex | Financial ratios, efficiency optimization |

| MOLP | Multiple linear functions | Goal programming, simplex | Resource allocation, production planning |

| Nonlinear MOO | Multiple nonlinear functions | Nature-inspired algorithms | Engineering design, complex systems |

Core Methodological Approaches

Scalarization Techniques for MOLFP

Scalarization approaches transform multi-objective problems into single-objective formulations, enabling the application of modified simplex methods. The weighted sum method represents one of the most widely used scalarization techniques, where objective functions are aggregated according to preferences of the decision maker [17]. However, this aggregation leads to a fractional function where the linear numerator and denominator of each objective function become polynomials, creating a challenging optimization problem that is "much more removed from convex programming than other multiratio problems" [17].

The desirability function approach provides an alternative methodology that merges multiple responses into a total desirability index (D) [12]. This approach scales individual responses between 0 and 1 using transformation functions:

- For responses to be maximized: ( dk = \begin{cases} 1 & yk > Tk \ \left(\frac{yk - Lk}{Tk - Lk}\right)^{wk} & Lk \leq yk \leq Tk \ 0 & yk < L_k \end{cases} )

- For responses to be minimized: ( dk = \begin{cases} 1 & yk < Tk \ \left(\frac{yk - Uk}{Tk - Uk}\right)^{wk} & Tk \leq yk \leq Uk \ 0 & yk > U_k \end{cases} )

- The overall desirability: ( D = \sqrt[K]{\prod{k=1}^K dk} )

where ( Tk ), ( Uk ), and ( Lk ) represent target, upper, and lower values respectively, and ( wk ) denotes weights determining the relative importance of reaching ( T_k ) [12]. A critical advantage of the desirability approach is its ability to deliver optima belonging to the Pareto set, preventing selection of a solution worse than an alternative in all responses [12].

Computational Framework and Simplex Adaptations

Recent computational advances have led to techniques that optimize the weighted sum of linear fractional objective functions by strategically searching the solution space [17]. The fundamental idea involves dividing the non-dominated region into sub-regions and analyzing each to determine which can be discarded if the maximum weighted sum lies elsewhere [17]. This process creates a search tree that efficiently narrows the solution space while identifying weight indifference regions where different weight vectors lead to the same non-dominated solution [17].

The grid-compatible simplex algorithm variant enables experimental deployment to coarsely gridded data typical of early-stage bioprocess development [12]. This approach preprocesses the gridded search space by assigning monotonically increasing integers to factor levels and replaces missing data points with highly unfavorable surrogate values [12]. The method proceeds iteratively, suggesting test conditions for evaluation and converting obtained responses into new test conditions until identifying an optimum [12].

Figure 1: Computational Workflow for MOLFP Problems

Experimental Protocols and Implementation

Protocol 1: Desirability-Based Scalarization for Bioprocess Optimization

Purpose: To optimize multiple conflicting responses in bioprocess development using desirability functions coupled with grid-compatible simplex methods.

Materials and Reagents:

- Experimental system with controllable input variables

- Analytical methods for response quantification

- Computational implementation of desirability functions

Procedure:

- Define Objective Functions: Identify key responses (e.g., yield, impurity levels, cost) and classify each as to be maximized or minimized.

- Establish Constraints: Set lower (( Lk )) and upper (( Uk )) limits for each response based on regulatory requirements or operational constraints.

- Set Target Values: Define target values (( T_k )) representing ideal performance for each response.

- Assign Weights: Specify weights (( w_k )) determining the relative importance of each response.

- Compute Individual Desirabilities: For each experimental condition, calculate individual desirability values (( d_k )) using appropriate transformation functions.

- Calculate Overall Desirability: Compute the overall desirability index (D) as the geometric mean of individual desirabilities.

- Grid-Compatible Simplex Optimization: Implement the simplex algorithm to maximize D by iteratively moving toward more favorable experimental conditions.

Applications: This approach has demonstrated particular success in high-throughput chromatography case studies with three responses (yield, residual host cell DNA content, and host cell protein content), effectively identifying operating conditions belonging to the Pareto set [12].

Protocol 2: Weighted Sum Optimization for MOLFP

Purpose: To solve MOLFP problems by converting them to single-objective problems through weighted sum aggregation.

Materials:

- Computational environment capable of linear programming

- Algorithm for solving linear fractional programs

Procedure:

- Problem Formulation: Express the MOLFP problem with p linear fractional objective functions and linear constraints.

- Weight Selection: Choose a weight vector ( \lambda = (\lambda1, \lambda2, ..., \lambdap) ) where ( \lambdai > 0 ) and ( \sum \lambda_i = 1 ).

- Create Composite Objective: Form the weighted sum of objective functions: ( \max \sum{k=1}^p \lambdak \frac{ckx + \alphak}{dkx + \betak} ).

- Region Division: Divide the feasible region into sub-regions and compute ideal points for each region.

- Region Elimination: Discard regions where the weighted sum of the ideal point is worse than achievable values in other regions.

- Iterative Refinement: Repeat the division and elimination process until remaining regions are sufficiently small.

- Solution Extraction: Identify the optimal solution from the remaining regions.

Applications: This technique has demonstrated computational efficiency in solving MOLFP problems, with performance tests indicating its superiority over existing approaches for various problem sizes [17].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of MOLFP Solution Methods

| Method | Problem Size (Variables × Objectives) | Computational Efficiency | Solution Quality | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weighted Sum with Region Elimination | 20 × 3 | High | Pareto Optimal | Systematic region discarding reduces computation |

| Desirability with Grid Simplex | 6 × 3 | Medium-High | Pareto Optimal | Handles experimental noise effectively |

| Fuzzy Interval Center Approximation | 15 × 2 | Medium | Efficient Solutions | Handles parameter uncertainty |

| Traditional Goal Programming | 20 × 3 | Low-Medium | Satisficing Solutions | Well-established, intuitive |

Technical Specifications and Computational Tools

Research Reagent Solutions for Optimization Experiments

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for MOLFP Implementation

| Tool Category | Specific Implementation | Function in MOLFP | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Linear Programming Solvers | Simplex algorithm implementations | Solving transformed LP subproblems | All MOLFP applications |

| Desirability Functions | Custom software modules | Scalarizing multiple responses | Bioprocess optimization, chromatography |

| Grid Management | Space discretization tools | Handling experimental design spaces | High-throughput screening |

| Weight Sensitivity Analysis | Parametric programming | Exploring trade-off surfaces | Decision support systems |

| Pareto Front Visualization | Multi-dimensional plotting | Presenting solution alternatives | Final decision making |

Advanced Computational Techniques

Recent algorithmic advances include a technique that divides the non-dominated region in the approximate "middle" into two sub-regions and analyzes each to discard regions that cannot contain the optimal solution [17]. This process builds a search tree where regions can be eliminated when the value of the weighted sum of their ideal point is worse than values achievable in other regions [17]. The computational burden primarily involves computing ideal points for each created region, requiring solution of a linear programming problem for each objective function [17].

For challenging problems with strong nonlinear effects, the grid-compatible simplex method has demonstrated remarkable efficiency, requiring "sub-minute computations despite its higher order mathematical functionality compared to DoE techniques" [12]. This efficiency persists even with complex data trends across multiple responses, making it particularly suitable for early bioprocess development studies [12].

Figure 2: Region Elimination Process for Efficient MOLFP Solution

Applications in Pharmaceutical Development

MOLFP techniques have demonstrated significant utility in pharmaceutical development, particularly in high-throughput bioprocess optimization. Case studies in chromatography optimization have successfully applied desirability-based simplex methods to simultaneously optimize yield, residual host cell DNA content, and host cell protein content [12]. These applications successfully identified operating conditions belonging to the Pareto set while offering "superior and balanced performance across all outputs compared to alternatives" [12].

The grid-compatible simplex method has proven particularly valuable in early development stages where high-throughput studies are routinely implemented to identify attractive process conditions for further investigation [12]. In these applications, the method consistently identified optima rapidly despite challenging response surfaces with strong nonlinear effects [12].

A key advantage in pharmaceutical contexts is the method's ability to avoid deterministic specification of response weights by including them as inputs in the optimization problem, thereby facilitating the decision-making process [12]. This approach empowers decision-makers by accounting for uncertainty in weight definition while efficiently exploring the trade-off space between competing objectives.

Foundational simplex techniques for Multi-Objective Linear Fractional Programming provide powerful methodological frameworks for addressing complex optimization problems with multiple competing objectives expressed as ratios. The integration of scalarization methods, particularly desirability functions and weighted sum approaches, with adapted simplex algorithms enables effective navigation of complex solution spaces to identify Pareto-optimal solutions.

These methodologies demonstrate particular value in pharmaceutical and bioprocess development contexts, where multiple quality and efficiency metrics must be balanced simultaneously. The computational efficiency of modern implementations, coupled with their ability to handle real-world experimental constraints, positions these techniques as essential components of the optimization toolkit for researchers and drug development professionals facing multi-objective decision challenges.

In many scientific and engineering domains, including drug discovery, decision-makers are faced with the challenge of optimizing multiple, often conflicting, objectives simultaneously. Multi-objective optimization provides a mathematical framework for addressing these challenges, with Pareto optimality serving as a fundamental concept for identifying solutions where no objective can be improved without worsening another [8]. This article details the core principles of Pareto optimality, solution sets, and trade-off analysis, framed within the context of multi-objective response function simplex research for pharmaceutical applications.

The Pareto front—the set of all Pareto optimal solutions—provides a comprehensive view of the trade-offs between competing objectives, enabling informed decision-making without presupposing subjective preferences [8]. For researchers in drug development, where balancing efficacy, safety, and synthesizability is paramount, these concepts are particularly valuable for navigating complex design spaces [18] [19].

Core Concepts and Definitions

Pareto Optimality and Dominance

In multi-objective optimization, a solution is considered Pareto optimal if no objective can be improved without degrading at least one other objective [8]. Formally, for a minimization problem with ( k ) objective functions ( f1(x), f2(x), \ldots, f_k(x) ), a solution ( x^* \in X ) is Pareto optimal if there does not exist another solution ( x \in X ) such that:

- ( fi(x) \leq fi(x^*) ) for all ( i \in {1, \dots, k} ), and

- ( fj(x) < fj(x^*) ) for at least one index ( j ) [8].

The corresponding objective vector ( f(x^*) ) is called non-dominated [20]. The set of all Pareto optimal solutions constitutes the Pareto optimal set, and the image of this set in the objective function space is the Pareto front [21].

Solution Sets in Multi-Objective Optimization

- Nondominated Set: Given a set of solutions, the non-dominated solution set contains all solutions not dominated by any other member of the set [21].

- Supported vs. Unsupported Solutions: Supported non-dominated points are those not dominated by any convex combination of other solutions, whereas unsupported points are dominated by such combinations but remain non-dominated within the discrete solution set [20].

- m-Minimal Solutions: An element ( \bar{x} \in S ) is an m-minimal solution if there exists no other ( x \in S ) such that ( F(x) \leq^m F(\bar{x}) ) and ( F(x) \neq F(\bar{x}) ), where ( \leq^m ) is a set order relation based on the Minkowski difference [22].

Trade-off Analysis

Trade-off analysis involves quantifying the compromises between competing objectives. The ideal objective vector ( z^{ideal} ) and nadir objective vector ( z^{nadir} ) provide lower and upper bounds, respectively, for the values of objective functions in the Pareto optimal set, helping to contextualize the range of possible trade-offs [8]. Quantitative measures like the Integrated Preference Functional (IPF) evaluate how well a set of solutions represents the Pareto set by calculating the expected utility over a range of preference parameters [20].

Application in Drug Discovery and Development

Multi-Objective Challenges in Drug Design

Drug discovery requires balancing numerous properties, including biological activity (e.g., binding affinity to protein targets), pharmacokinetics (e.g., solubility, metabolic stability), safety (e.g., low toxicity), and synthesizability (e.g., synthetic accessibility score) [18] [19]. These objectives are often conflicting; for example, increasing molecular complexity to improve binding affinity may reduce synthetic accessibility or worsen drug-likeness.

Pareto Optimization Methods

Recent advances employ Pareto-based algorithms to navigate this complex design space:

- Pareto Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS): Methods like PMMG and ParetoDrug use MCTS to explore the chemical space and identify molecules on the Pareto front. These approaches balance exploration and exploitation through schemes like ParetoPUCT, efficiently generating novel compounds satisfying multiple property constraints [18] [19].

- Genetic Algorithms: SMILES-GA utilizes genetic algorithms to mutate and cross SMILES string representations, evolving populations of molecules toward the Pareto front [18].

- Reinforcement Learning: REINVENT applies reinforcement learning to fine-tune generative models, though it has often been limited to optimizing only a few properties simultaneously [18].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Multi-Objective Molecular Generation Algorithms

| Method | Hypervolume (HV) | Success Rate (SR) | Diversity (Div) | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PMMG | 0.569 ± 0.054 | 51.65% ± 0.78% | 0.930 ± 0.005 | MCTS with Pareto front search, handles 7+ objectives |

| SMILES-GA | 0.184 ± 0.021 | 3.02% ± 0.12% | - | Genetic algorithm with SMILES representation |

| SMILES-LSTM | - | - | - | Long Short-Term Memory neural networks |

| MARS | - | - | - | Graph neural networks with MCMC sampling |

| Graph-MCTS | - | - | - | Graph-based Monte Carlo Tree Search |

Table 2: Key Molecular Properties in Multi-Objective Drug Design

| Property | Description | Target/Optimization Goal | Typical Range/Scale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Docking Score | Predictive binding affinity to target protein | Maximize (higher = stronger binding) | Negative value of binding energy |

| QED | Quantitative Estimate of Drug-likeness | Maximize | [0, 1] |

| SA Score | Synthetic Accessibility score | Minimize (lower = easier to synthesize) | - |

| LogP | Lipophilicity (partition coefficient) | Within optimal range | -0.4 to +5.6 (Ghose filter) |

| Toxicity | Predicted adverse effects | Minimize | Varies by metric |

| Solubility | Ability to dissolve in aqueous solution | Maximize | [0, 100] for permeability |

Benefit-Risk Trade-off Analysis in Clinical Development

In clinical decision-making, benefit-risk assessment applies similar trade-off analysis principles. Quantitative approaches include:

- Incremental Net Benefit: Computes the weighted difference between benefits and risks, incorporating preference weights [23].

- Benefit-Risk Ratio: Compares the probability of benefit to the probability of harm [23].

- Individual Patient Benefit-Risk Profiles: Models that predict each patient's specific benefit and risk based on their characteristics, enabling personalized therapeutic decisions [24].

Table 3: Quantitative Benefit-Risk Assessment Methods

| Method | Formula/Approach | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Numbers Needed to Treat (NNT) | NNT = 1 / (Event rate in control - Event rate in treatment) | Cardiovascular trials, antithrombotic agents [23] |

| Benefit-Risk Ratio | Ratio of probability of benefit to probability of harm | Vorapaxar in patients with myocardial infarction [23] |

| Incremental Net Benefit | INB = λ × (Benefit difference) - (Risk difference) | Weighted benefit-risk assessment [23] |

| Individual Benefit-Risk | Multivariate regression predicting individual outcomes | Personalized vorapaxar recommendations [24] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Pareto Monte Carlo Tree Search for Molecular Generation

Purpose: To generate novel drug-like molecules with multiple optimized properties using Pareto-based MCTS.

Materials:

- Pretrained RNN or autoregressive generative model (e.g., trained on SMILES strings)

- Property prediction models (docking, QED, SA Score, etc.)

- Chemical database for initial training (e.g., BindingDB [19])

Methodology:

- Tree Initialization: Begin with a root node representing an empty molecular structure.

- Selection: Traverse the tree using a selection policy (e.g., Upper Confidence Bound) that balances exploration of new branches and exploitation of promising paths.

- Expansion: Add new child nodes by extending the molecular structure (e.g., adding atoms or fragments) using the pretrained generative model for guidance.

- Simulation: Roll out the molecular construction to completion, generating a full SMILES string.

- Evaluation: Compute all relevant objective functions for the generated molecule (e.g., docking score, QED, SA Score).

- Backpropagation: Update node statistics in the traversal path based on the multi-objective evaluation.

- Pareto Front Maintenance: Maintain a global pool of non-dominated solutions, updating it with new candidates that are not dominated by existing solutions [18] [19].

Validation:

- Calculate performance metrics: Hypervolume Indicator, Success Rate, and Diversity [18].

- Compare generated molecules to known active compounds for target proteins.

- Verify synthetic accessibility and drug-likeness thresholds.

Protocol 2: SIMPLEX Optimization with Multi-Objective Response Functions

Purpose: To optimize analytical flow techniques (e.g., Flow Injection Analysis) using SIMPLEX method with multi-objective response functions.

Materials:

- Flow-injection analysis system with adjustable parameters (e.g., tube diameters, injection volume, flow rates)

- Standard solutions for calibration

- Detection instrumentation (e.g., spectrophotometer)

Methodology:

- Parameter Selection: Identify key variables to optimize (e.g., reaction time, reagent volume, flow rate).

- Response Function Formulation: Define a multi-objective response function that combines normalized objectives: [ RF = \sum{i} wi \cdot Ri - \sum{j} wj \cdot Rj^* ] where ( Ri ) are desirable characteristics (e.g., sensitivity) normalized via ( R = \frac{R{exp} - R{min}}{R{max} - R{min}} ), and ( Rj^* ) are undesirable characteristics (e.g., analysis time) normalized via ( R^* = 1 - \frac{R{exp} - R{min}}{R{max} - R{min}} ) [25].

- Initial SIMPLEX Formation: Create an initial geometric simplex with ( n+1 ) vertices for ( n ) parameters.

- Iterative Optimization: a. Evaluate response function at each vertex. b. Identify worst-performing vertex and reflect it through the centroid of the opposite face. c. Apply parameter threshold constraints to avoid impractical conditions. d. Continue reflection, expansion, or contraction steps until convergence [25].

- Validation: Verify optimal conditions through univariant or factorial studies around the identified optimum.

Protocol 3: Tchebycheff Scalarization for Evaluating Solution Sets

Purpose: To evaluate and compare sets of non-dominated solutions using Tchebycheff utility functions.

Materials:

- Set of candidate non-dominated solutions

- Weighted Tchebycheff function: ( u(z) = \max{i} { wi |zi - zi^{ideal}| } ) [20]

Methodology:

- Weight Set Partitioning:

- For each pair of non-dominated points ( z^a ) and ( z^b ), find the break-even weight vector ( w^{ab} ) where ( u(z^a) = u(z^b) ) [20].

- Partition the weight space into regions where each solution is optimal.

- Integrated Preference Functional (IPF) Calculation:

- For each weight region ( Wa ) where solution ( z^a ) is optimal, compute: [ IPFa = \int{Wa} u(z^a(w)) f(w) dw ] where ( f(w) ) is the probability density function over weights [20].

- Aggregate ( IPF_a ) across all solutions to evaluate the solution set's overall quality.

- Expected Utility Calculation:

- Compute the expected utility for individual solutions over the entire parameter space to assess their robustness to preference uncertainties [20].

Visualization of Workflows

Pareto MCTS Molecular Generation Workflow

SIMPLEX Multi-Objective Optimization Procedure

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 4: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Multi-Objective Optimization

| Item | Type | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| BindingDB | Database | Public database of protein-ligand binding affinities for training and validation [19] |

| smina | Software Tool | Docking software for calculating binding affinity between molecules and target proteins [19] |

| SMILES Representation | Data Format | String-based molecular representation enabling genetic operations and machine learning [18] |

| Recurrent Neural Network (RNN) | Computational Model | Generative model for molecular structure prediction using SMILES strings [18] |

| Tchebycheff Utility Function | Mathematical Function | Scalarization approach for evaluating solutions under multiple objectives [20] |

| Hypervolume Indicator | Metric | Measures volume of objective space dominated by a solution set, quantifying performance [18] |

| Weight Set Partitioning | Algorithm | Divides preference parameter space for IPF calculation and solution evaluation [20] |

From Theory to Practice: Implementing Simplex and Hybrid Frameworks for Drug Discovery

The integration of the Simplex algorithm with Game Theory and Taylor Series approximations represents a sophisticated methodological framework for addressing complex multi-objective optimization problems. This hybrid approach is particularly relevant in pharmaceutical development, where researchers must simultaneously optimize numerous conflicting objectives such as drug efficacy, toxicity, cost, and manufacturability. By leveraging the strategic decision-making capabilities of Game Theory with the local approximation power of Taylor Series, this enhanced Simplex framework provides a robust mechanism for navigating high-dimensional response surfaces. The following application notes and protocols detail the implementation, validation, and practical application of this hybrid methodology within the context of multi-objective response function simplex research for drug development.

Multi-objective optimization presents significant challenges in drug development, where researchers must balance competing criteria such as potency, selectivity, metabolic stability, and synthetic complexity. Traditional Simplex methods, while efficient for single-objective optimization, encounter limitations in these complex landscapes. The integration of Game Theory principles, specifically Nash Equilibrium concepts, enables the identification of compromise solutions where no single objective can be improved without degrading another [26]. Simultaneously, Taylor Series approximations facilitate efficient local landscape exploration, reducing computational requirements while maintaining solution quality.

This hybrid framework operates through a coordinated interaction between three computational paradigms: the directional optimization of Nelder-Mead Simplex, the strategic balancing of Game Theory, and the local approximation capabilities of Taylor Series expansions. When applied to pharmaceutical development, this approach enables systematic navigation of complex chemical space while explicitly addressing the trade-offs between critical development parameters.

Theoretical Foundation and Algorithmic Integration

Game Theory Integration for Multi-Objective Balancing

The incorporation of Game Theory transforms the multi-objective optimization problem into a strategic game where each objective function becomes a "player" seeking to optimize its outcome [26]. In this framework:

- Players: Represent individual objective functions (e.g., efficacy, toxicity, cost)

- Strategies: Correspond to adjustments in decision variables (e.g., chemical structure modifications, process parameters)

- Payoffs: Reflect improvements in respective objective functions

The algorithm seeks Nash Equilibrium solutions where no player can unilaterally improve their position, mathematically defined as:

This equilibrium state represents a Pareto-optimal solution where all objectives are balanced appropriately [26]. For drug development applications, this ensures that improvements in one attribute (e.g., potency) do not disproportionately compromise other critical attributes (e.g., safety profile).

Taylor Series Expansion for Local Response Surface Modeling

Taylor Series approximations provide a mathematical foundation for predicting objective function behavior within the neighborhood of current simplex vertices. For a multi-objective response function F(x) = [f₁(x), f₂(x), ..., fₖ(x)], the second-order Taylor expansion around a point x₀ is:

Where J(x₀) is the Jacobian matrix of first derivatives and H(x₀) is the Hessian matrix of second derivatives. This approximation enables the algorithm to predict objective function values without expensive re-evaluation, significantly reducing computational requirements during local search phases.

Integrated Hybrid Algorithm Workflow

The complete hybrid algorithm integrates these components through a structured workflow that balances exploration and exploitation while maintaining computational efficiency. The following Graphviz diagram illustrates this integrated workflow:

Application Notes for Pharmaceutical Development

Multi-Objective Optimization in Lead Compound Identification

The hybrid algorithm demonstrates particular utility in lead compound identification and optimization, where multiple pharmacological and physicochemical properties must be balanced simultaneously. The following table summarizes key objectives and their relative weighting factors determined through Game Theory analysis:

Table 1: Multi-Objective Optimization Parameters in Lead Compound Identification

| Objective Function | Pharmaceutical Significance | Target Range | Weighting Factor | Game Theory Player |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Binding Affinity (pIC₅₀) | Primary efficacy indicator | >7.0 | 0.25 | Efficacy Player |

| Selectivity Index | Safety parameter against related targets | >100-fold | 0.20 | Safety Player |

| Metabolic Stability (t₁/₂) | Pharmacokinetic optimization | >60 min | 0.15 | PK Player |

| CYP Inhibition | Drug-drug interaction potential | IC₅₀ > 10 µM | 0.15 | DDI Player |

| Aqueous Solubility | Formulation development | >100 µg/mL | 0.10 | Developability Player |

| Synthetic Complexity | Cost and manufacturability | <8 steps | 0.10 | Cost Player |

| Predicted Clearance | In vivo performance | <20 mL/min/kg | 0.05 | PK Player |

Implementation of the hybrid algorithm for this application follows a structured protocol that integrates computational predictions with experimental validation:

Experimental Protocol for Lead Optimization Cycle

Protocol Title: Hybrid Algorithm-Driven Lead Optimization for Enhanced Drug Properties

Objective: Systematically improve lead compound profiles through iterative application of the hybrid Simplex-Game Theory-Taylor Series algorithm.

Materials and Reagents:

- Compound library with structural diversity

- High-throughput screening assays for primary and secondary pharmacology

- ADME-Tox screening platforms (e.g., microsomal stability, CYP inhibition)

- Physicochemical property assessment tools (e.g., solubility measurement)

- Cheminformatics software for structural analysis

Procedure:

Initial Simplex Design (Week 1)

- Select 10-15 initial compounds representing chemical space diversity

- Determine baseline values for all objective functions in Table 1

- Establish simplex vertices in multi-dimensional objective space

Game Theory Weight Assignment (Week 1)

- Convene project team including medicinal chemistry, pharmacology, and DMPK experts

- Assign initial weighting factors through Delphi method consensus building

- Establish Nash Equilibrium targets for objective trade-offs

Iterative Optimization Cycle (Weeks 2-8)

- Perform Taylor Series approximation to predict compound performance

- Apply Game Theory to identify optimal direction in chemical space

- Generate new compound designs based on algorithmic recommendations

- Synthesize 5-10 proposed compounds per iteration

- Evaluate all objective functions for new compounds

- Update simplex vertices based on performance data

Convergence Assessment (Week 9)

- Monitor algorithm convergence using Minkowski distance metric

- Confirm Pareto-optimality of solution candidates

- Select 2-3 lead candidates for advanced profiling

Validation Metrics:

- Algorithm convergence within 6-8 iterations

- Improvement in at least 4 objective functions without degradation in others

- Experimental confirmation of predicted compound properties

Computational Implementation and Signaling Pathways

Algorithmic Decision Pathway

The hybrid algorithm employs a sophisticated decision pathway that integrates the three methodological components. The following Graphviz diagram illustrates the signaling and decision logic within a single optimization iteration:

Research Reagent Solutions for Implementation

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Hybrid Algorithm Implementation

| Reagent/Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function in Protocol | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Optimization Algorithms | Custom MATLAB/Python implementation, NLopt library | Core algorithmic operations | Must support constrained multi-objective optimization |

| Cheminformatics Platforms | RDKit, OpenBabel, Schrodinger Suite | Compound structure representation and manipulation | Enables chemical space navigation and property prediction |

| Biological Screening Assays | HTRF binding assays, fluorescence-based enzyme assays | Objective function quantification | High-throughput implementation critical for rapid iteration |

| ADME-Tox Profiling | Hepatocyte stability assays, Caco-2 permeability, hERG screening | Safety and PK objective functions | Miniaturized formats enable higher throughput |

| Physicochemical Assessment | HPLC solubility measurement, logP determination | Developability objectives | Automated systems improve throughput and reproducibility |

| Data Management | KNIME pipelines, custom databases | Objective function data integration | Critical for algorithm input and historical trend analysis |

| Visualization Tools | Spotfire, Tableau, Matplotlib | Results interpretation and decision support | Enables team understanding of multi-dimensional optimization |

Advanced Protocols for Specific Applications

Protocol for Formulation Optimization

Protocol Title: Multi-Objective Formulation Development Using Hybrid Algorithm

Application Context: Optimization of drug formulation parameters to balance stability, bioavailability, manufacturability, and cost.

Experimental Design:

Define Decision Variables

- Excipient ratios (e.g., filler:binder:disintegrant)

- Processing parameters (e.g., compression force, moisture content)

- Particle engineering parameters

Establish Objective Functions

- Stability profile (degradation rate)

- Dissolution performance (Q-value at critical timepoints)

- Powder flow properties

- Tablet hardness and friability

- Raw material and manufacturing cost

Implement Hybrid Algorithm

- Initial simplex spanning formulation space

- Game Theory weighting based on product requirements

- Taylor Series modeling of excipient interaction effects

Validation Approach: Confirm optimal formulations exhibit predicted balance of properties through accelerated stability studies and pilot-scale manufacturing.

Protocol for Clinical Dose Optimization

Protocol Title: Hybrid Algorithm for Clinical Dose Regimen Optimization

Application Context: Determination of optimal dosing regimens balancing efficacy, safety, and convenience.

Methodology:

Population Pharmacokinetic/Pharmacodynamic Modeling

- Develop structural PK/PD models from Phase I/II data

- Identify key parameters as decision variables

Multi-Objective Framework

- Efficacy: Target attainment probability

- Safety: Adverse event incidence

- Convenience: Dosing frequency, formulation burden

Algorithm Implementation

- Simplex exploration of dosing parameter space

- Game Theory negotiation between clinical objectives

- Taylor Series approximation of exposure-response relationships