Optimizing Analytical Method Sensitivity: A Comprehensive Guide for Robust Pharmaceutical Analysis

This article provides a systematic guide for researchers and drug development professionals on optimizing sensitivity in analytical methods.

Optimizing Analytical Method Sensitivity: A Comprehensive Guide for Robust Pharmaceutical Analysis

Abstract

This article provides a systematic guide for researchers and drug development professionals on optimizing sensitivity in analytical methods. It covers foundational principles, advanced methodological approaches including Design of Experiments (DoE) and Quality by Design (QbD), practical troubleshooting strategies for common issues, and rigorous validation and comparative techniques. By integrating modern optimization strategies, machine learning, and robust validation frameworks, this resource aims to equip scientists with the knowledge to develop highly sensitive, reliable, and transferable analytical procedures that meet stringent regulatory standards and enhance drug development outcomes.

Core Principles and Strategic Planning for Enhanced Analytical Sensitivity

Core Concepts: Understanding LOD and LOQ

What are the fundamental parameters for defining sensitivity in pharmaceutical analysis?

In pharmaceutical analysis, Limit of Detection (LOD) and Limit of Quantitation (LOQ) are two critical parameters used to define the sensitivity of an analytical method. They describe the smallest concentrations of an analyte that can be reliably detected or quantified, which is essential for detecting low levels of impurities, degradation products, or active ingredients.

- Limit of Detection (LOD) is the lowest concentration of an analyte that can be reliably distinguished from the analytical noise or a blank sample, but not necessarily quantified as an exact value. It is a limit for detection, confirming the analyte's presence or absence [1] [2] [3].

- Limit of Quantitation (LOQ) is the lowest concentration of an analyte that can be quantitatively determined with acceptable precision (repeatability) and accuracy (trueness). It is the limit for reliable quantification [1] [4].

The following table summarizes the key features of LOD and LOQ:

| Parameter | Definition | Primary Use | Key Distinction |

|---|---|---|---|

| LOD (Limit of Detection) | The lowest analyte concentration that can be reliably distinguished from background noise [1] [2]. | Qualitative detection of impurities or contaminants [2]. | Confirms the analyte is present [2]. |

| LOQ (Limit of Quantitation) | The lowest analyte concentration that can be quantified with stated accuracy and precision [1] [4]. | Quantitative determination of impurities or degradation products [2]. | Determines how much of the analyte is present [1]. |

How are LOD and LOQ mathematically determined?

Several established approaches can be used to determine LOD and LOQ. The following table outlines the common methodologies [2] [4] [3].

| Method | LOD Calculation | LOQ Calculation | Best Suited For |

|---|---|---|---|

| Signal-to-Noise Ratio (S/N) | S/N = 3:1 [2] [3] | S/N = 10:1 [2] [4] | Chromatographic methods (e.g., HPLC) with a stable baseline [2]. |

| Standard Deviation of the Blank and Slope | 3.3 × (σ/S) [2] [5] | 10 × (σ/S) [2] [5] | Instrumental methods where a calibration curve is used. σ = SD of response; S = slope of calibration curve [5]. |

| Standard Deviation of the Blank (Clinical/CLSI EP17) | Meanblank + 1.645(SDblank) [1] | LOQ ≥ LOD, defined by precision and bias goals [1] | Clinical laboratory methods, using blank sample replicates. |

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

FAQ: Why are my calculated LOD and LOQ values fluctuating over time?

Unexpected fluctuations in detection limits can be caused by several factors, including deteriorating instrument calibration, changes in environmental conditions (like temperature), contaminated reagents, matrix interferences, and aging detector components [3]. Regular instrument maintenance, calibration, and using high-quality, fresh reagents are essential for stable performance.

FAQ: How often should we revalidate the LOD and LOQ for an established method?

LOD and LOQ should be revalidated during the initial full method validation, after any major instrument changes or repairs, and periodically as part of method monitoring. A good practice is to revalidate them annually for critical methods, or whenever your system suitability or performance qualification data indicates a potential loss of sensitivity [3].

Troubleshooting Guide: Low Sensitivity in HPLC Methods

Problem: The observed detection sensitivity is lower than expected during an HPLC analysis.

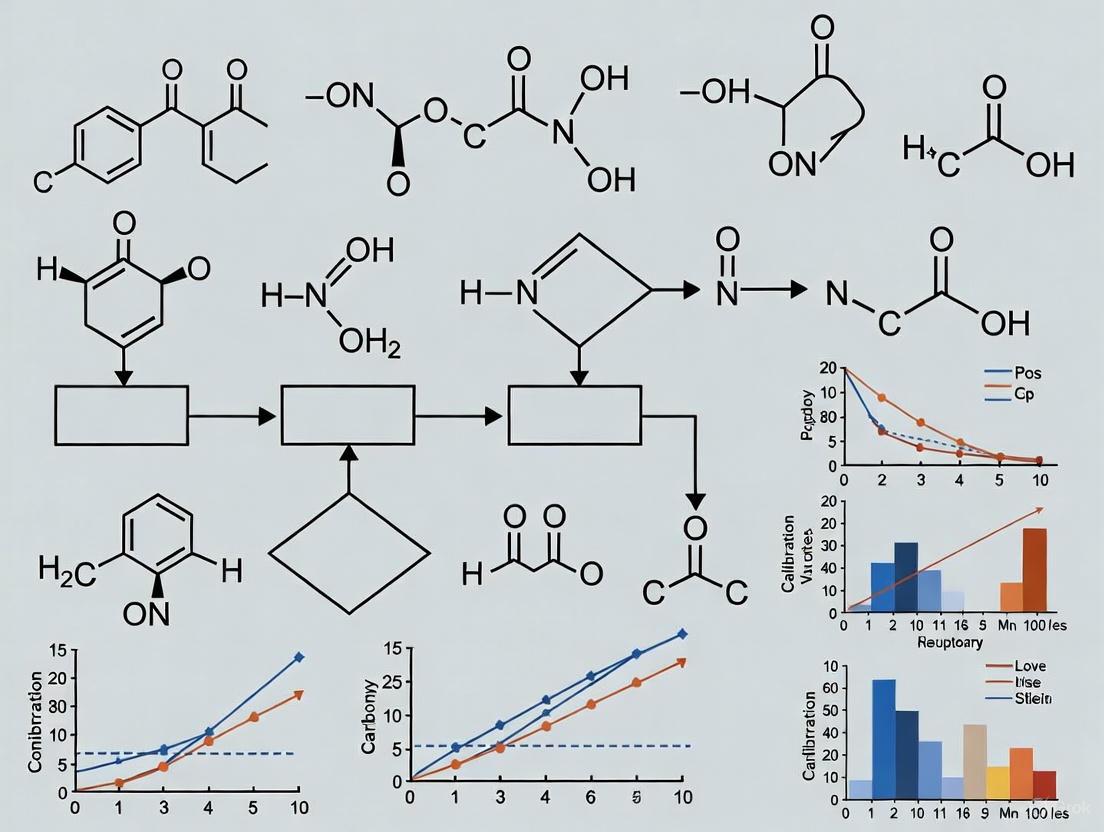

This is a common issue with many potential physical, chemical, and methodological causes. The flowchart below outlines a systematic approach to troubleshooting.

Common Causes and Solutions:

Column-Related Issues:

- Decreased Column Efficiency: Over time, columns can degrade, leading to broader peaks and lower peak height (sensitivity). A decrease in plate number by a factor of four can halve the peak height [6]. Solution: Replace the aging column.

- Incorrect Column Diameter: A larger column diameter than optimal can lead to peak broadening and reduced sensitivity [6]. Solution: Use a column with a smaller internal diameter to increase peak height and sensitivity [7].

- Analyte Adsorption: "Sticky" molecules (like some proteins or nucleotides) can adsorb to surfaces in the flow path, reducing the amount that reaches the detector [6]. Solution: "Prime" the system by making multiple injections of the analyte to saturate adsorption sites before running critical samples [6].

Detector and Signal Issues:

- Lack of Chromophore: If using a UV-Vis detector, the analyte must contain a chromophore (a functional group that absorbs light). Analytes like sugars are weak UV absorbers and will show poor sensitivity [6]. Solution: Consider using a different detection technique (e.g., refractive index or mass spectrometry).

- Low Data Acquisition Rate: If the data acquisition rate is too low, the chromatographic peak will be poorly defined, with fewer data points, leading to an apparent decrease in peak height [6]. Solution: Increase the data acquisition rate to ensure each peak is defined by a sufficient number of data points.

Sample and Methodological Issues:

- Sample Solvent Strength: If the sample is dissolved in a solvent stronger than the initial mobile phase, peak broadening and fronting can occur, reducing sensitivity [7]. Solution: Ensure the sample solvent is compatible with and preferably weaker than the starting mobile phase.

- Sample Loss: Analyte can be lost during preparation steps due to adsorption to vial walls, incomplete extraction, or degradation [3]. Solution: Review and optimize the sample preparation protocol, considering different materials (e.g., low-adsorption vials) or additives.

Method Optimization: Increasing Sensitivity for LOD/LOQ

How can I optimize my HPLC method to achieve a lower LOQ?

If your method is robust but lacks the required sensitivity, consider these optimization strategies:

- Switch from Isocratic to Gradient Elution: Gradient runs often produce sharper, narrower peaks compared to isocratic runs, resulting in higher peak heights and better signal-to-noise ratios [7].

- Optimize Column Parameters:

- Reduce Column Diameter: Moving from a 4.6 mm to a 3 mm internal diameter column can significantly increase peak height and sensitivity while reducing solvent consumption [7].

- Use Smaller Particle Sizes: Columns with smaller particles (e.g., 3 μm vs. 5 μm) can provide higher efficiency and sharper peaks. This can be combined with a shorter column to maintain analysis time and backpressure [7].

- Consider Core-Shell Particles: These particles can provide high efficiency with lower backpressure, leading to narrower peaks and improved sensitivity [7].

- Optimize Sample Preparation: Incorporate a sample concentration step or use derivatization to enhance the analyte's detector response [3].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Determining LOD and LOQ via Calibration Curve in Excel

This method uses the standard deviation of the response and the slope of the calibration curve for a statistically robust determination [5].

Research Reagent Solutions:

| Reagent / Material | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Analyte Standard | The pure substance used to prepare known concentrations for the calibration curve. |

| Blank Solution | The matrix without the analyte, used to measure background signal. |

| Mobile Phase | The solvent system used to elute the analyte in the HPLC system. |

| Microsoft Excel | Software for performing regression analysis and calculations. |

Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Prepare Calibration Standards: Dilute the analyte standard to create a series of solutions with concentrations in the expected low range of LOD/LOQ.

- Analyze and Plot Standard Curve: Inject each standard into your analytical instrument (e.g., HPLC). Plot the resulting data with concentration on the X-axis and the instrument response (e.g., peak area) on the Y-axis [5].

- Perform Regression Analysis: Use the Data Analysis > Regression tool in Excel. Select your concentration data as the "X Range" and your response data as the "Y Range". The tool will generate an output sheet [5].

- Extract Key Parameters: From the regression output, you need:

- Standard Deviation of the Y-Intercept (σ or Syx): This is the "Standard Error" value listed in the regression statistics.

- Slope of the Calibration Curve (S): This is the "X Variable 1 Coefficient" [5].

- Calculate LOD and LOQ: Use the following formulas [2] [5]:

- LOD = 3.3 × (σ / S)

- LOQ = 10 × (σ / S)

Protocol 2: Verification of LOQ using Precision and Accuracy

Once a provisional LOQ is calculated, its reliability must be verified experimentally [1] [4].

Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Prepare Test Samples: Prepare at least five replicates of a sample spiked with the analyte at the calculated LOQ concentration [4].

- Analyze the Samples: Process and analyze all replicates using the validated method.

- Calculate Precision and Accuracy:

- Precision: Calculate the % Coefficient of Variation (%CV) of the measured concentrations of the replicates.

- Accuracy: Calculate the % Relative Error (%RE) by comparing the mean measured concentration to the known (spiked) concentration.

- %RE = [(Mean Measured Concentration - Known Concentration) / Known Concentration] × 100

- Acceptance Criteria: For the LOQ to be valid, the predefined goals for bias and imprecision must be met. A common acceptance criterion in bioanalysis is that both %CV and absolute %RE should be ≤ 20% at the LOQ [4]. If these criteria are not met, the LOQ should be set at a slightly higher concentration and the verification process repeated [1].

Troubleshooting Guides

Poor Analytical Sensitivity and Signal Quality

Problem: Low signal-to-noise ratio, poor detection limits, or unexplained signal suppression during analysis, particularly for ionizable compounds or oligonucleotides.

| Symptom | Potential Root Cause Related to Physicochemical Properties | Troubleshooting Steps | Preventive Measures |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low signal-to-noise in MS detection | Analyte adsorption to surfaces or microparticulates; metal adduct formation (e.g., with Na+, K+) obscuring the target signal [8]. | • Use plastic (non-glass) containers for mobile phases and samples to prevent alkali metal leaching [8].• Flush the LC system with 0.1% formic acid to remove metal ions from the flow path [8].• Incorporate a size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) cleanup step to separate analytes from metal ions [8]. | • Use MS-grade solvents and freshly purified water [8].• Integrate a strategic SEC dimension in 2D-LC methods for complex samples [8]. |

| Irreproducible retention times and peak shape | Incorrectly accounted ionization state of the analyte due to unpredicted pH shifts, altering LogD and interaction with the stationary phase [9]. | • Check and adjust the pH of mobile phases precisely; use buffers with adequate capacity [9].• Experimentally determine the analyte's pKa and LogD at the method's pH [9] [10]. | • During method development, profile LogD across a physiologically relevant pH range (e.g., 1.5-7.4) to understand analyte behavior [9]. |

| Unexpectedly low recovery in sample preparation | Poor solubility or inappropriate LogD at the extraction pH, leading to incomplete dissolution or partitioning [11] [12]. | • Adjust the pH of the extraction solvent to suppress ionization and improve efficiency (for liquid-liquid extraction) [9].• Switch to a different solvent or sorbent more compatible with the analyte's LogD [12]. | • Consult measured solubility and LogP/LogD data early in method development to guide sample prep design [11] [10]. |

| Wavy or unstable UV baseline | Air bubbles in the detector flow cell or a sticky pump check valve, often exacerbated by solvent viscosity changes from method adjustments [8]. | Change one thing at a time [8]: First, flush the flow cell with isopropanol. If the problem persists, then switch to pre-mixed mobile phase to isolate the pump as the cause [8]. | • Plan troubleshooting experiments carefully to avoid unnecessary parts replacement and knowledge loss [8].• Ensure proper mobile phase degassing. |

Inconsistent or Supersaturated Solutions

Problem: Inconsistent sample concentrations due to precipitation or the formation of metastable supersaturated solutions, leading to highly variable analytical results.

| Symptom | Potential Root Cause Related to Physicochemical Properties | Troubleshooting Steps | Preventive Measures |

|---|---|---|---|

| Precipitation in stock or working standards | The compound's solubility product is exceeded, or the solution has become supersaturated and spontaneously crystallizes [11]. | • Warm the solution to re-dissolve precipitate (if the compound is thermally stable), then cool slowly while mixing [11].• Re-prepare the standard in a solvent system where the compound is more soluble (e.g., with a small amount of co-solvent like DMSO) [11]. | • Understand the intrinsic solubility (LogS0) of the compound [11].• Use a dissolution medium with a pH that favors the ionized (more soluble) form of the analyte [9] [10]. |

| Crystallization during an analytical run | The method's mobile phase conditions (pH, organic solvent strength) push a marginally soluble compound out of solution [11]. | • Dilute the sample in the initial mobile phase composition.• Reduce the injection volume to lower the mass load on the column.• Increase the organic modifier percentage in the mobile phase, if compatible with separation. | • During method development, assess the risk of supersaturation, which is more common in molecules with high melting points and numerous H-bond donors/acceptors [11]. |

| Declining peak area over sequential injections | Compound precipitation within the chromatographic system (e.g., in the injector loop, tubing, or column head) [11]. | • Implement a stronger needle wash solvent.• Include a conditioning step with a strong solvent between injections.• Change the column inlet frit or flush the column. | • Characterize the physical form and solubility profile of the analyte during the pre-method development phase [11] [10]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: How do pKa and LogP fundamentally differ, and why does both matter for analytical sensitivity?

A1: pKa and LogP are distinct but interconnected properties. pKa measures the acidity or basicity of a molecule, defining the pH at which half of the molecules are ionized [10]. LogP measures the lipophilicity (fat/water preference) of the unionized form of a molecule [9]. The critical link is that ionization drastically changes lipophilicity. The true lipophilicity at a specific pH is given by LogD, which accounts for all species (ionized and unionized) present [9] [12]. For sensitivity, if an analyte is too lipophilic (high LogD), it may stick to surfaces or have poor elution; if too hydrophilic (low LogD), it may not be retained or extracted efficiently. Knowing pKa allows you to predict and control LogD via pH, thus optimizing recovery and detection [9] [11].

Q2: What is a "good" LogP value for a drug candidate, and does this apply to analytical methods?

A2: For an oral drug candidate, a LogP between 2 and 5 is often considered optimal, balancing solubility in aqueous blood with the ability to cross lipid membranes [9]. However, in analytical chemistry, there is no single "good" value. The ideal LogP/LogD is context-dependent on the method [10]. For a reversed-phase LC method, a moderate LogD at the method pH is typically desired for optimal retention. For a liquid-liquid extraction, a high LogD is targeted for efficient partitioning into the organic phase. The goal is to manipulate the system (e.g., pH) to achieve a favorable LogD for your specific analytical step [9] [12].

Q3: How can pH manipulation be used strategically to improve method performance?

A3: pH is a powerful tool because it directly controls the ionization state of ionizable analytes. You can use it to:

- Maximize Retention in Reversed-Phase LC: For a basic analyte, use a pH at least 2 units above its pKa to keep it unionized, increasing lipophilicity (LogD) and retention.

- Minimize Retention for Early Elution: For the same basic analyte, use a low pH to protonate it (ionize it), reducing LogD and retention time.

- Optimize Extraction Efficiency: In sample prep, adjust the pH to ensure the analyte is in its uncharged form (high LogD) for efficient transfer into an organic solvent [9].

- Enhance Solubility: To prevent precipitation and column clogging, use a pH that keeps the analyte charged and soluble in the aqueous component of the mobile phase [10].

Q4: What are the best practices for developing a robust and sensitive analytical method from a physicochemical perspective?

A4:

- Gather Property Data Early: Use in silico tools or experimental services to determine key properties like pKa, LogP, and intrinsic solubility (LogS0) before method development [10] [12].

- Profile LogD vs. pH: Understand how your analyte's lipophilicity changes across the pH scale, especially in physiologically relevant ranges (e.g., 1.5-7.4) for bioanalytical methods [9].

- Embrace QbD and Risk Assessment: Follow a Quality-by-Design (QbD) approach. Use a risk assessment to systematically evaluate critical method parameters (like pH, solvent strength) on performance and robustness [13].

- Change One Variable at a Time: During troubleshooting and optimization, alter only one parameter at a time to clearly understand its effect [8].

- Plan for Sustainability: Consider the greenness of your method. Strategies like automation, miniaturization, and solvent reduction can improve safety, reduce costs, and lessen environmental impact without sacrificing sensitivity [14].

Relationship Between Physicochemical Properties and BCS Classification

Research on 84 marketed ionizable drugs reveals how measured LogP and intrinsic solubility (LogS0) can predict a drug's Biopharmaceutics Classification System (BCS) category, which is critical for anticipating analytical challenges related to solubility and permeability [11].

| BCS Class | Solubility | Permeability | Typical Clustering on LogP vs. LogS0 Plot | Associated Physicochemical Trends |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class I | High | High | Clustered in a favorable region [11]. | Generally lower LogP and higher LogS0; balanced properties [11]. |

| Class II | Low | High | Clustered in regions of higher LogP and lower LogS0 [11]. | High lipophilicity is the primary driver of low solubility [11]. |

| Class III | High | Low | Clustered separately from Class I and II [11]. | Lower LogP; solubility is high but permeability is limited by other factors [11]. |

| Class IV | Low | Low | Not explicitly clustered in the study [11]. | Challenging properties; often have high melting points and multiple H-bond donors/acceptors [11]. |

Impact of Pooling on PCR Efficiency and Sensitivity

A study on SARS-CoV-2 testing demonstrates how sample pooling, a strategy to increase capacity, directly impacts analytical sensitivity (as measured by Cycle threshold (Ct) shift and % sensitivity), providing a model for understanding how sample matrix and dilution affect detection [15].

| Pool Size | Estimated Ct Shift | Reagent Efficiency | Analytical Sensitivity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (Individual) | 0 | 1x | ~100% (Baseline) |

| 4 | - | Most significant gain [15] | 87.18 - 92.52 [15] |

| 8 | - | No considerable savings beyond this point [15] | - |

| 12 | - | - | 77.09 - 80.87 [15] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Determination of pKa and LogP via Potentiometric Titration

This method is a standard for determining both pKa and LogP simultaneously [10].

1. Principle: The method relies on monitoring the change in pH as acid or base is added to a solution of the compound. For LogP, the compound is partitioned between an aqueous phase and a water-immiscible organic solvent (like octanol) during the titration, and the shift in the titration curve is used to calculate the partition coefficient [10].

2. Materials and Reagents:

- Sirius T3 instrument (or equivalent analytical titrator) [10].

- pH-electrode and reference electrode.

- Magnetic stirrer.

- High-purity water, 0.5 M KCl, 0.1 M HCl (for acid titrations), 0.1 M KOH (for base titrations).

- 1-Octanol (HPLC grade).

- Sample: 2-5 mg of solid compound [10].

3. Procedure: 1. System Preparation: Calibrate the pH electrode according to the instrument's SOP. Ensure all glassware is clean and dry. 2. Aqueous Titration: - Dissolve the sample in a known volume of water and 0.5 M KCl (to maintain constant ionic strength). - Purge the solution with inert gas (e.g., N2) to exclude CO2. - Titrate with either 0.1 M HCl or KOH to generate a titration curve in the aqueous system alone. 3. Biphasic Titration: - Repeat the titration, but now include an equal volume of 1-octanol in the titration vessel. - The compound will partition between the two phases, and the titration curve will shift. 4. Data Acquisition: Monitor the pH change continuously as titrant is added. The instrument software will record the entire titration curve.

4. Data Analysis:

- The pKa is determined from the inflection points of the titration curve [10].

- The LogP is calculated by the instrument's software from the difference between the titration curves in the presence and absence of octanol [10].

- The software can also calculate LogD at pH 7.4 based on the measured pKa and LogP values [10].

Protocol: Measuring LogP using a Robust HPLC-Based Method

This method uses Reverse-Phase High Performance Liquid Chromatography (RP-HPLC) as a faster, more resource-sparing alternative to the shake-flask method [16].

1. Principle: The retention time of a compound on a reverse-phase column correlates with its lipophilicity. By calibrating the column with compounds of known LogP, a relationship is established to determine the LogP of unknown compounds [16].

2. Materials and Reagents:

- HPLC system with a UV detector.

- Reverse-phase C18 column.

- Mobile Phase: Mixtures of a water-miscible organic solvent (e.g., methanol or acetonitrile) and a buffer (e.g., phosphate or acetate).

- Standard compounds with known LogP values (e.g., carbamazepine, ibuprofen) [16].

- Sample solution of the test compound.

3. Procedure: 1. Mobile Phase Calibration: - Run a gradient method (e.g., from 5% to 95% organic modifier) to determine the approximate retention of the analyte. - Choose at least three different isocratic mobile phase conditions (e.g., 60%, 70%, 80% organic) under which the compound elutes with a retention factor (k) between 1 and 10. 2. System Calibration: - Inject each standard compound at each isocratic condition and record their retention times (Tr). Calculate the retention factor (k) for each. - For each standard, plot log k against the % organic modifier. Extrapolate to 0% organic to obtain log kw. 3. Sample Analysis: - Inject the test compound under the same isocratic conditions and calculate its log kw. 4. Establish Correlation: - Plot the known LogP values of the standards against their calculated log kw. Perform linear regression to obtain the equation: LogP = a * log k*w + b.

4. Data Analysis:

- Calculate the log kw for your unknown compound.

- Use the calibration equation to convert this log kw value into a predicted LogP value [16].

Property-Sensitivity Relationship Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship between fundamental physicochemical properties and their combined impact on the critical analytical outcome of sensitivity.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

This table details essential materials and their functions for experiments determining pKa, LogP, and solubility.

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Sirius T3 Instrument | An automated analytical tool for performing potentiometric and spectrophotometric titrations to determine pKa, LogP, and LogD [10]. | Provides comprehensive data; requires specific training and is a significant investment. Suitable for high-throughput labs or dedicated service providers [10]. |

| 1-Octanol | The standard non-polar solvent used in the shake-flask method and potentiometric titrations to model biological membranes [9] [12]. | Must be high-purity to avoid impurities affecting partitioning. The aqueous phase is typically buffered to a specific pH for LogD measurements [9]. |

| Reverse-Phase C18 Column | The stationary phase for HPLC-based LogP determination. Its hydrophobic surface interacts with analytes based on their lipophilicity [16]. | Column chemistry and age can affect retention times. Method requires calibration with known standards for accurate LogP prediction [16]. |

| High-Purity Buffers | Used to control pH in mobile phases, pKa determinations, and solubility studies. Precise pH is critical for accurate and reproducible results [9] [8]. | Buffer capacity must be sufficient for the analyte. Incompatibility with MS detection (e.g., phosphate buffers) must be considered [8]. |

| MS-Grade Solvents & Additives | High-purity solvents and additives (e.g., formic acid) used in LC-MS to minimize background noise and suppress adduct formation [8]. | Essential for achieving high sensitivity in mass spectrometric detection, especially for challenging analytes like oligonucleotides [8]. |

| Non-Glass (Plastic) Containers | Used for storing mobile phases and samples in sensitive MS workflows to prevent leaching of alkali metal ions (Na+, K+) that cause signal suppression and adduct formation [8]. | A simple but critical practice for maintaining optimal MS performance for certain applications [8]. |

Core Principles of QbD in Analytical Method Development

Quality by Design (QbD) is a systematic, science-based, and risk-management approach to analytical and pharmaceutical development. It transitions quality assurance from a reactive model (testing quality into the product) to a proactive one (designing quality into the product from the outset) [17]. For researchers focused on optimizing analytical method sensitivity, QbD provides a structured framework to develop robust, reliable, and fit-for-purpose methods.

The table below summarizes the core components of the QbD framework as defined by ICH guidelines [18].

Table 1: Core Components of the QbD Framework

| QbD Component | Description | Role in Method Development |

|---|---|---|

| Quality Target Product Profile (QTPP) | A prospective summary of the quality characteristics of a drug product. | For method development, this translates to the Analytical Target Profile (ATP), defining the method's intended purpose and required performance. |

| Critical Quality Attributes (CQAs) | Physical, chemical, biological, or microbiological properties that must be controlled within appropriate limits. | These are the key performance indicators of the method, such as accuracy, precision, specificity, and sensitivity (LOQ/LOD). |

| Critical Material Attributes (CMAs) & Critical Process Parameters (CPPs) | Input variables (e.g., reagent purity, column temperature, flow rate) that significantly impact the method's CQAs. | Factors like mobile phase composition, column temperature, or detector settings that are systematically evaluated. |

| Design Space | The multidimensional combination and interaction of input variables demonstrated to provide assurance of quality. | The established, validated ranges for all CMAs and CPPs within which the method performs as intended without requiring re-validation. |

| Control Strategy | A planned set of controls derived from product and process understanding. | A system of procedures and checks to ensure the method remains in a state of control during routine use. |

| Lifecycle Management | Continuous monitoring and improvement of the method throughout its operational life. | Ongoing method verification and performance trending, allowing for updates based on accumulated data. |

The systematic workflow for implementing QbD is a logical, sequential process. The following diagram illustrates the relationship between the core components.

QbD Troubleshooting Guide: Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: How can I use QbD to improve the robustness of my analytical method and reduce variability?

Challenge: Method performance is sensitive to small, deliberate variations in parameters, leading to inconsistent results between analysts, instruments, or laboratories.

Solution: Employ a structured QbD approach to systematically identify and control factors that influence method CQAs.

- Step 1: Define Robustness as a CQA. In your ATP, specify that the method must be robust, meaning it should be unaffected by small, intentional changes in operational parameters.

- Step 2: Identify Potential Risk Factors. Use risk assessment tools (e.g., Fishbone diagrams, FMEA) to identify all method parameters that could impact robustness (e.g., mobile phase pH, column temperature, flow rate, gradient time) [17].

- Step 3: Conduct a Robustness Study Using DoE. Instead of the traditional "one-factor-at-a-time" (OFAT) approach, use a statistically designed experiment (DoE) to efficiently evaluate the simultaneous impact of multiple parameters and their interactions on your CQAs [17] [18].

- Step 4: Establish a Control Strategy. Based on the DoE results, define the acceptable ranges for each critical parameter within the method's design space. Document these as controlled parameters in the method procedure to ensure they are consistently adhered to, thereby minimizing variability.

FAQ 2: My method lacks the required specificity and sensitivity. How can QbD help me optimize it?

Challenge: The method cannot adequately distinguish the analyte from interferences (specificity) or fails to detect and quantify at low enough levels (sensitivity).

Solution: Utilize QbD principles to gain a deeper understanding of the method's operational boundaries and systematically optimize for performance.

- Step 1: Prioritize Specificity and Sensitivity as CQAs. Clearly state the required detection/quantification limits and specificity criteria in your ATP.

- Step 2: Leverage DoE for Optimization. Apply DoE to optimize critical parameters that govern sensitivity and specificity. For a chromatographic method, this could include:

- Factors: Column chemistry (C18 vs. embedded polar group vs. fluorinated) [19], mobile phase composition (organic solvent ratio, buffer type and pH), and detector settings.

- Responses: Signal-to-noise ratio (for sensitivity), resolution from nearest eluting peak (for specificity), and peak asymmetry.

- Step 3: Explore the Design Space. The DoE will help you map a design space where the optimal balance between sensitivity, specificity, and other CQAs (like analysis time) is achieved. This allows you to operate at a "sweet spot" for maximum performance [18].

FAQ 3: How do I effectively identify which method parameters are truly "Critical" (CPPs)?

Challenge: It is difficult and time-consuming to determine which of the many method parameters have a significant impact on the CQAs and therefore need strict control.

Solution: Implement a science- and risk-based screening process.

- Step 1: Initial Risk Assessment. Use prior knowledge (scientific literature, platform methods, vendor data) and risk assessment tools to categorize parameters as High, Medium, or Low risk.

- Step 2: Screening DoE. For parameters deemed high or medium risk, a screening DoE (e.g., a fractional factorial or Plackett-Burman design) can be used. This efficiently screens a large number of factors to identify the few truly critical ones that have a major effect on the CQAs [17].

- Step 3: Focused Development. Focus your development and validation efforts on these confirmed CPPs, saving time and resources while ensuring control is applied where it matters most.

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Developing an LC-MS Method Using a QbD Approach

This protocol outlines the key stages for developing a robust and sensitive Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS) method for small molecule analysis using QbD principles.

Objective: To develop a sensitive, specific, and robust LC-MS method for the quantification of [Analyte Name] in [Matrix Type], achieving an LOQ of ≤1 ng/mL.

Phase 1: Pre-Development and Planning

Define the Analytical Target Profile (ATP): Create a summary of the method's requirements.

- Table 2: Example Analytical Target Profile (ATP)

Attribute Target Intended Purpose Quantification of [Analyte] in human plasma Accuracy 85-115% Precision (%RSD) ≤15% at LOQ, ≤10% for other QCs Specificity No interference from matrix or known metabolites Linearity Range 1 - 500 ng/mL LOQ (Sensitivity) 1 ng/mL (S/N ≥ 10) Robustness Tolerant to small variations in pH (±0.1), flow rate (±0.05 mL/min), and column temperature (±2°C)

- Table 2: Example Analytical Target Profile (ATP)

Identify CQAs: From the ATP, the CQAs are defined as: Accuracy, Precision, Specificity, Sensitivity (LOQ), and Linearity.

Risk Assessment: Conduct an initial risk assessment to identify potential CMAs and CPPs.

- Tool: Fishbone (Ishikawa) Diagram.

- Categories: Instrument, Method, Materials, Environment, Analyst.

- High-Risk Parameters Identified for Screening: Column chemistry (CMA), mobile phase pH (CPP), buffer concentration (CPP), gradient slope (CPP), source temperature (CPP), and flow rate (CPP).

Phase 2: Method Development and Optimization

Screening DoE:

- Objective: Identify the most influential CPPs on CQAs (e.g., Peak Area, S/N Ratio, Resolution).

- Design: A fractional factorial or Plackett-Burman design.

- Factors: Include the high-risk parameters from the risk assessment.

- Execution: Perform experiments as per the design and statistically analyze the results (e.g., using Pareto charts) to identify 2-3 most critical CPPs.

Optimization DoE:

- Objective: Find the optimal operational conditions and define the method's design space.

- Design: A Response Surface Methodology (RSM) design like Central Composite Design (CCD).

- Factors: The 2-3 critical CPPs identified in the screening study (e.g., mobile phase pH, gradient time).

- Responses: Key CQAs (e.g., S/N Ratio, Resolution, Retention Time).

- Execution: Run the experiments, fit a mathematical model to the data, and generate contour plots to visualize the design space.

Phase 3: Design Space Verification and Control Strategy

- Verify the Design Space: Perform confirmatory experiments at the edge of the established design space to verify that the model accurately predicts method performance.

- Formal Method Validation: Perform a full method validation (accuracy, precision, specificity, linearity, range, robustness) according to ICH Q2(R1) within the defined design space [20].

- Document Control Strategy: The final method procedure will specify the controlled settings for the identified CPPs (e.g., "Mobile phase pH must be 3.5 ± 0.1") and the frequency of system suitability tests to ensure ongoing performance.

The following diagram visualizes the experimental design and optimization process.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

The following table lists key materials and solutions commonly used in QbD-driven chromatographic method development.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for QbD Method Development

| Item / Solution | Function / Purpose | QbD Consideration (CMA) |

|---|---|---|

| Chromatographic Columns (e.g., C18, Embedded Polar Group, PFP) | Provides the stationary phase for separation. Different chemistries offer orthogonal selectivity [19]. | LOT-to-LOT variability is a key CMA. Testing from multiple lots during development is recommended for robustness. |

| HPLC/MS Grade Solvents (e.g., Acetonitrile, Methanol, Water) | Serves as the mobile phase components. High purity is critical to minimize background noise and baseline drift. | Purity and UV-cutoff are CMAs. Impurities can affect baseline, sensitivity, and peak shape. |

| Buffer Salts (e.g., Ammonium Formate, Ammonium Acetate, Phosphate Salts) | Modifies mobile phase pH and ionic strength to control analyte ionization, retention, and peak shape. | pH and buffer concentration are critical CPPs/CMAs. They must be precisely prepared and controlled. |

| Additives (e.g., Formic Acid, Trifluoroacetic Acid, Ammonium Hydroxide) | Modifies mobile phase pH to suppress or promote analyte ionization, improving chromatography and MS detection. | Concentration and purity are CMAs. Small variations can significantly impact retention time and MS response. |

| Reference Standards | Highly characterized substance used to confirm identity, potency, and for quantification. | Purity and stability are critical CMAs. Must be stored and handled according to certificate of analysis. |

Identifying Critical Method Parameters and Risk Assessment

Frequently Asked Questions

What are Critical Method Parameters and how do they differ from Critical Quality Attributes?

Critical Method Parameters (CMPs) are the specific variables in an analytical procedure that must be controlled to ensure the method consistently produces valid results. Unlike Critical Quality Attributes (CQAs), which are the measurable properties that define product quality, CMPs directly impact the reliability of the measurement itself. CMPs typically include factors like chromatographic flow rate, column temperature, mobile phase pH, detection wavelength, and injection volume. If these parameters vary beyond established ranges, they can compromise method accuracy, precision, and specificity—even when the product quality itself hasn't changed [21] [22].

Why is a systematic risk assessment crucial for identifying true Critical Method Parameters?

A systematic risk assessment is essential because it provides a science-based justification for focusing validation efforts on parameters that truly impact method performance. Without proper risk assessment, laboratories often waste resources over-controlling minor parameters while missing significant ones. The International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) Q9 guideline emphasizes quality risk management as a fundamental component of pharmaceutical quality systems. A structured approach ensures that method validation targets the most influential factors, enhancing efficiency while maintaining regulatory compliance [21] [23].

What are the most common issues when transferring methods between laboratories?

Method transfer failures typically stem from insufficient robustness testing during initial validation and undocumented parameter sensitivities. Common issues include retention time shifts in chromatography due to subtle mobile phase preparation differences, variability in sample preparation techniques between analysts, equipment disparities between sending and receiving laboratories, and environmental factors not adequately addressed in the original method. These problems can be minimized by applying rigorous risk assessment during method development to identify and control truly critical parameters [24] [22].

How can I determine if a method parameter is truly "critical"?

A parameter is considered critical when small variations within a realistic operating range significantly impact the method's results. This determination should be based on experimental data, typically through Design of Experiments (DOE) studies. The effect size is calculated by comparing the parameter's influence to the product specification tolerance. As a general guideline, parameters causing changes greater than 20% of the specification tolerance are typically classified as critical, those between 11-19% are key operating parameters, and those below 10% are generally not practically significant [21].

What documentation is required to support Critical Method Parameter identification?

Robust documentation should include the risk assessment report, experimental designs (DOE matrices), statistical analysis of parameter effects, justification for classification decisions, and established control strategies. Regulatory agencies expect this documentation to demonstrate a clear "line-of-sight" between CMPs and method CQAs. The documentation should be thorough enough to withstand regulatory scrutiny and support successful technology transfers to other laboratories or manufacturing sites [21] [24].

Troubleshooting Guides

Poor Method Robustness

Symptoms: Inconsistent results between analysts, instruments, or laboratories; method fails system suitability tests during transfer.

| Possible Cause | Investigation Approach | Corrective Actions |

|---|---|---|

| Underspecified method parameters | Conduct robustness testing using DOE to identify influential factors [21] | Modify method to explicitly control sensitive parameters; expand system suitability criteria |

| Inadequate method validation | Review validation data for gaps in robustness testing [22] | Supplement with additional studies focusing on parameter variations |

| Uncontrolled environmental factors | Monitor lab conditions (temperature, humidity) and correlate with method performance | Implement environmental controls; add conditioning steps |

Resolution Protocol:

- Perform a retrospective risk assessment to identify potential uncontrolled parameters

- Design a limited DOE to evaluate the effects of these parameters

- Based on results, revise method procedures to explicitly control influential factors

- Update validation documentation to reflect the enhanced controls

- Implement ongoing monitoring to ensure control effectiveness

Unexpected Specificity Failures

Symptoms: Interfering peaks in chromatograms; inability to separate analytes from impurities; variable baseline.

| Possible Cause | Investigation Approach | Corrective Actions |

|---|---|---|

| Mobile phase composition sensitivity | Methodically vary organic ratio, pH, or buffer concentration [25] | Optimize and narrow acceptable ranges; implement tighter controls |

| Column temperature sensitivity | Evaluate separation at different temperatures | Add column temperature control with specified tolerances |

| Column lot-to-lot variability | Test method with columns from different manufacturers or lots [25] | Specify column manufacturer and quality controls; add system suitability tests |

Resolution Protocol:

- Verify that specificity was properly validated including forced degradation studies

- Systematically vary chromatographic conditions to identify optimal separation parameters

- Assess alternative columns with different selectivity characteristics

- Enhance sample preparation to remove interferents

- Update method with refined conditions and additional system suitability requirements

Inconsistent Precision Performance

Symptoms: High variability in results; failure to meet precision acceptance criteria; unpredictable method behavior.

| Possible Cause | Investigation Approach | Corrective Actions |

|---|---|---|

| Sample preparation variability | Evaluate each preparation step for contribution to variability | Standardize and control critical preparation steps |

| Instrument parameter drift | Monitor key instrument parameters during sequence runs | Implement preventative maintenance; add control checks |

| Insufficient parameter control | Use statistical analysis to identify uncontrolled influential factors [21] | Apply tighter controls to identified critical parameters |

Resolution Protocol:

- Conduct a gage R&R study to quantify different sources of variation

- Identify the largest contributors to variability through statistical analysis

- Implement additional controls for the dominant variation sources

- Establish tighter monitoring for these parameters

- Revise method to include enhanced control procedures

Experimental Protocols

Systematic Approach to Parameter Identification and Ranking

Objective: To identify and rank method parameters based on their criticality through a structured risk assessment and experimental verification process.

Materials and Equipment:

- Standard and sample materials

- Appropriate analytical instrumentation

- DOE software for experimental design and statistical analysis

- Documentation templates for risk assessment and results recording

Procedure:

Define Method Goals and CQAs

- Identify all Critical Quality Attributes the method must measure [21]

- Establish the Analytical Target Profile defining method requirements

- Document the "ideal method" performance characteristics

Initial Risk Assessment

- Brainstorm all potential method parameters using process flow diagrams

- Apply risk ranking based on scientific knowledge and prior experience

- Use risk assessment tools (e.g., FMEA, Fishbone diagrams) to identify high-risk parameters [21]

- Document rationale for parameter prioritization

Experimental Design

- Select key factors identified during risk assessment for experimental verification

- Design a multivariate study (DOE) to efficiently evaluate parameter effects

- Ensure the design space adequately represents normal operational ranges

- Include center points to estimate variability and curvature

Execution and Data Collection

- Conduct experiments according to the designed matrix

- Monitor all responses related to method CQAs

- Ensure proper replication to estimate experimental error

- Document all conditions and results thoroughly

Data Analysis and Parameter Classification

- Analyze data using statistical methods to determine factor significance

- Calculate effect sizes for each parameter relative to specification tolerances

- Classify parameters using established criticality thresholds:

- Critical: Effect size >20% of tolerance

- Key: Effect size 11-19% of tolerance

- Non-critical: Effect size <10% of tolerance [21]

- Document classification decisions with supporting data

Control Strategy Development

- Establish appropriate controls for critical and key parameters

- Define operational ranges for each controlled parameter

- Implement monitoring systems to ensure parameter control

- Develop response plans for out-of-control situations

Workflow Visualization

Quantitative Parameter Assessment Protocol

Objective: To quantitatively assess the impact of method parameters and determine their criticality using statistical measures.

Procedure:

Experimental Design Setup

- Select parameters for evaluation based on initial risk assessment

- Define high and low levels for each parameter representing realistic operational ranges

- Create a resolution IV or higher design to estimate main effects clear of two-factor interactions

- Include center points to estimate pure error and check for curvature

Response Measurement

- Execute the experimental design using appropriate standards and samples

- Measure all relevant responses (retention time, peak area, resolution, etc.)

- Ensure randomization to minimize bias

- Replicate center points to estimate experimental variability

Statistical Analysis

- Analyze data using multiple linear regression

- Calculate scaled estimates (half-effects) for each parameter

- Convert to full effects: Full Effect = Scaled Estimate × 2

- Compute percentage of tolerance: % Tolerance = |Full Effect| / (USL - LSL) × 100

Criticality Classification

- Apply classification criteria based on percentage of tolerance:

| Effect Size (% Tolerance) | Parameter Classification | Control Requirement |

|---|---|---|

| > 20% | Critical | Strict control with narrow operating ranges |

| 11-19% | Key | Moderate control with defined ranges |

| < 10% | Non-critical | General monitoring only |

- Document classification decisions with supporting statistical evidence

- Verify classifications with confirmatory experiments

The Scientist's Toolkit

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent/Material | Function in Parameter Assessment | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Standards | Quantify method accuracy and precision during parameter studies | Use certified reference materials with documented purity [22] |

| Chromatographic Columns | Evaluate separation performance under varied parameters | Test multiple column lots and manufacturers [25] |

| Buffer Components | Assess pH and mobile phase sensitivity | Prepare with tight control of concentration and pH [22] |

| System Suitability Mixtures | Monitor system performance during parameter studies | Contains critical analyte pairs to challenge separation |

| Quality Control Samples | Verify method performance across parameter variations | Representative matrix with known analyte concentrations |

Risk Assessment Tools and Applications

| Assessment Tool | Application in Parameter Identification | Implementation Guidance |

|---|---|---|

| FMEA (Failure Mode and Effects Analysis) | Systematic evaluation of potential parameter failure modes | Use risk priority numbers to prioritize parameters [21] |

| Fishbone Diagrams | Visualize all potential sources of method variability | Brainstorm parameters across people, methods, materials, machines, environment |

| Risk Ranking Matrix | Compare and prioritize parameters based on impact and occurrence | Apply standardized scoring criteria for consistency |

| Process Flow Diagrams | Identify parameters at each method step | Map analytical procedure from sample preparation to data analysis |

| Design of Experiments | Statistically verify parameter criticality | Use fractional factorial designs for screening numerous parameters [21] |

Setting Analytical Target Profiles (ATPs) and Defining Goals for Sensitivity Optimization

An Analytical Target Profile (ATP) is a foundational document in analytical method development that prospectively defines the performance requirements a method must meet to be fit for its intended purpose [26]. For research focused on optimizing analytical sensitivity, the ATP provides critical goals for key attributes such as the Limit of Detection (LOD), accuracy, and precision [26]. Establishing a clear ATP ensures that sensitivity optimization is a systematic and goal-oriented process, aligning method development with the demands of the pharmaceutical product and regulatory standards [26].

This guide addresses frequent challenges and questions you may encounter when defining ATPs and optimizing method sensitivity.

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Q1: How do I define appropriate sensitivity criteria (like LOD) in my ATP for a new method?

Defining sensitivity criteria is a critical first step. The ATP should clearly state the required LOD based on the analyte's clinical or quality relevance.

- Challenge: Setting an LOD that is either too strict (leading to costly and complex method development) or too lenient (risking failure to detect critical impurities).

- Solution:

- Understand the Context: The LOD must be low enough to detect the analyte at a level that is physiologically or toxicologically meaningful. For impurity methods, this is often tied to reporting thresholds stipulated by regulatory bodies.

- Base it on Signal and Noise: A common and practical approach is to determine the LOD based on the signal-to-noise ratio. The LOD is typically the analyte concentration that yields a signal-to-noise ratio of 3:1 [27].

- Use Statistical Methods: Alternatively, you can determine LOD through statistical analysis of the calibration curve or by measuring replicate blank samples. The ATP should specify which approach is used.

Q2: My method meets the LOD in the ATP, but results are inconsistent. What could be wrong?

Meeting the LOD is only one part of sensitivity; the method must also be robust and precise at that level.

- Challenge: High variability in results near the detection limit, leading to unreliable data.

- Solution & Investigation:

- Check Sample Preparation: Inconsistent sample extraction, dilution, or reconstitution can cause high variability. Ensure all steps are highly controlled and automated where possible.

- Review Matrix Effects: The sample matrix (e.g., plasma, formulation excipients) can suppress or enhance the analyte signal. Re-evaluate the method's selectivity and specificity as defined in your ATP. You may need to modify the sample clean-up process (e.g., solid-phase extraction) to better isolate the analyte.

- Verify Instrument Performance: Ensure the analytical instrument (e.g., HPLC detector, mass spectrometer) is performing optimally at low concentrations. Check baseline noise and carryover. System suitability testing is critical here to confirm the system's performance before analysis [26].

Q3: How can I demonstrate that my optimized method is "fit for purpose" as per the ATP?

A method is "fit for purpose" only when all performance characteristics outlined in the ATP are met consistently.

- Challenge: Providing comprehensive evidence that the method meets all ATP criteria beyond just sensitivity.

- Solution:

- Formal Method Validation: Conduct a full validation following ICH guidelines, directly testing against each attribute in the ATP. The table below summarizes key attributes and how they relate to sensitivity and overall fitness [26].

| ATP Attribute | Definition | Role in Sensitivity & Fitness |

|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | Closeness between measured and true value | Ensures quantitative results are reliable at all levels, including near the LOD. |

| Precision | Closeness of repeated measurements | Confirms the method produces consistent results, a key challenge at low concentrations. |

| Selectivity | Ability to measure analyte despite matrix | Directly impacts the signal-to-noise ratio and thus the achievable LOD. |

| Linearity & Range | Method's response is proportional to concentration | The LOD and LOQ define the lower end of the method's working range. |

| LOD/LOQ | Lowest detectable/quantifiable amount | The direct measures of analytical sensitivity. |

| Robustness | Resilience to small method variations | Ensures the optimized sensitivity is maintained during routine use. |

Experimental Protocols for Sensitivity Optimization

The following workflow provides a general framework for developing and optimizing a method with a specific focus on achieving the sensitivity targets in your ATP. This is particularly relevant for techniques like HPLC-UV or LC-MS.

Workflow Diagram: Sensitivity Optimization Path

Protocol 1: Optimizing Sample Preparation for Low-Level Analytes

Objective: To maximize analyte recovery and minimize interference, thereby improving the signal-to-noise ratio for a lower LOD.

Materials:

- Internal Standard: A structurally similar analog to the analyte used to correct for losses during preparation and instrument variability.

- Solid-Phase Extraction (SPE) Cartridges: For selective extraction and clean-up of the analyte from a complex matrix.

- Protein Precipitation Reagents: (e.g., Acetonitrile, Methanol) for removing proteins from biological samples.

- Evaporation System: (e.g., Nitrogen evaporator) to concentrate the sample.

Methodology:

- Spiking: Prepare calibration standards and QC samples by spiking the analyte into the blank matrix (e.g., plasma, buffer).

- Extraction: Test different sample preparation techniques (e.g., protein precipitation vs. SPE vs. liquid-liquid extraction).

- Compare Recovery: Calculate the percentage recovery for each method by comparing the peak response of the extracted sample to a non-extracted standard at the same concentration.

- Assess Matrix Effect: In LC-MS, post-column infuse the analyte and inject extracted blank matrix to check for ion suppression/enhancement zones.

- Concentrate: If needed, incorporate a solvent evaporation step and reconstitute in a smaller volume to pre-concentrate the sample.

Protocol 2: HPLC-UV Method Optimization for Enhanced Detection

Objective: To fine-tune chromatographic conditions and detection parameters to achieve a sharper, taller peak and a lower baseline, directly improving the LOD.

Materials:

- HPLC System: equipped with a UV/VIS or DAD detector.

- Analytical Column: (e.g., C18, 150 x 4.6 mm, 5 µm).

- Mobile Phase Components: High-purity water, organic solvents (Acetonitrile, Methanol), and buffers (e.g., Phosphate, Formate).

Methodology:

- Wavelength Selection: Use a Diode Array Detector (DAD) to identify the wavelength of maximum absorbance (( \lambda_{\text{max}} )) for the analyte.

- Mobile Phase pH and Composition: Systematically vary the pH of the aqueous buffer (± 0.5 pH units) and the percentage of organic solvent to improve peak shape (symmetry) and resolution from other components. A sharper peak gives a higher signal.

- Flow Rate: Test different flow rates (e.g., 0.8 - 1.2 mL/min). A lower flow rate can sometimes improve sensitivity by increasing the analyte's interaction with the detector cell.

- Column Temperature: Evaluate the impact of column temperature (e.g., 25°C - 40°C) on peak broadening.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists essential materials and their functions for developing sensitive analytical methods.

| Item | Function in Sensitivity Optimization |

|---|---|

| High-Purity Solvents & Reagents | Minimize baseline noise and ghost peaks in chromatograms, which is crucial for detecting low-level analytes. |

| Stable Isotope Labeled Internal Standard | Corrects for analyte loss during sample preparation and matrix effects in mass spectrometry, improving accuracy and precision at low concentrations. |

| Specialized SPE Sorbents | Selectively extract and concentrate the analyte from a complex sample matrix, improving the signal-to-noise ratio and reducing ion suppression in LC-MS. |

| Sensitive Detection Kits (e.g., ATP assays) | Kits like luciferase-based ATP bioluminescence assays provide a highly amplified signal for detecting extremely low levels of cellular contamination or biomass [28] [27]. |

| Advanced Analytical Columns | Columns with smaller particle sizes (e.g., sub-2µm) or specialized chemistries can provide superior chromatographic resolution, leading to sharper peaks and higher signal intensity. |

Key Takeaways for Your Research

Integrating sensitivity goals into your Analytical Target Profile (ATP) from the outset provides a clear roadmap for method development. When facing sensitivity challenges, systematically troubleshoot the sample preparation, analytical conditions, and instrument performance. Success is demonstrated not just by achieving a low LOD, but by validating that the entire method is precise, accurate, and robust at that level, ensuring it is truly fit-for-purpose in pharmaceutical development.

Advanced Methodologies and Practical Applications for Sensitivity Optimization

Leveraging Design of Experiments (DoE) for Efficient Parameter Optimization

Troubleshooting Guides

Why is my DoE failing to identify significant factor interactions?

Problem: Your experimental results show no significant factor interactions, or the model's predictive power is poor.

- Cause 1: Incorrect factor level selection. Levels set too close together may not produce detectable effects.

- Solution: Widen the range between low and high factor levels to evoke a measurable change in the response. Ensure levels are as far apart as reasonably possible while remaining within safe operating boundaries [29].

- Cause 2: Inadequate control of lurking variables. Uncontrolled environmental factors can mask true factor effects.

- Solution: Implement rigorous experimental controls. Randomize run order to minimize the impact of uncontrolled variables, and ensure all factors not being tested are kept constant [30] [31].

- Cause 3: Using a screening design when optimization is needed.

- Solution: Employ a multi-stage approach. Start with screening designs (e.g., fractional factorial) to identify vital few factors, then progress to response surface methodology (RSM) designs for optimization [30] [31].

How to address non-reproducible DoE results during validation?

Problem: Optimal conditions identified in DoE fail validation runs or scale-up.

- Cause 1: Insufficient sample size during testing, leading to statistically insignificant results.

- Solution: Scale the number of test units to the failure rate. To validate improvement for an issue with a 10% failure rate, test at least 30 units with zero observed failures for statistical confidence (α=0.05) [32].

- Cause 2: Over-reliance on simulated test conditions that don't reflect real-world variability.

- Solution: Validate tests with real-world conditions. Ensure your test environments accurately simulate actual usage scenarios, not just idealized factory conditions [32].

- Cause 3: Assembly or configuration errors during testing.

- Solution: Implement hyper-vigilance during assembly. Use visual inspection or in-person validation to ensure correct configurations and prevent kitting errors [32].

What to do when facing resource constraints for comprehensive DoE?

Problem: Limited time, materials, or budget prevents running full factorial designs.

- Cause 1: Attempting to study too many factors with inadequate resources.

- Solution: Use fractional factorial or Plackett-Burman designs to efficiently screen many factors with minimal runs [30] [31]. For 5+ factors, consider definitive screening designs that handle large factor numbers with reduced run size [29].

- Cause 2: Failure to leverage sequential experimentation.

- Solution: Implement a structured approach: begin with fractional factorial designs to identify critical factors, then focus resources on optimizing only those significant parameters with more detailed designs [30] [31].

- Cause 3: Not utilizing specialized software for design efficiency.

- Solution: Employ statistical software (Minitab, JMP, Design-Expert, MODDE) that can create optimal designs for constrained resources and automate analysis [31].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Is DoE only suitable for complex analytical methods?

Answer: No. While highly beneficial for complex methods, DoE applies to any method from simple dissolution testing to complex chromatography. The principles of identifying and optimizing factors apply universally. DoE can be particularly valuable for routine methods where small efficiency gains yield significant long-term benefits [30].

How do I select the right factors and levels for my DoE?

Answer: Factor selection requires both process knowledge and practical considerations:

- Brainstorming: Involve cross-functional teams to identify all potential influential variables [31].

- Historical Data: Review prior knowledge and preliminary experiments [30].

- Level Selection: Choose two levels as far apart as reasonable for continuous factors. For categorical factors, select the two most different levels believed to have the largest impact [29].

- Pilot Runs: Conduct small pilot experiments to check feasibility and refine factor ranges before full-scale experimentation [31].

What's the fundamental difference between DoE and one-factor-at-a-time (OFAT) approaches?

Answer: The key difference is that DoE changes multiple factors simultaneously and systematically, enabling detection of interactions between factors. OFAT changes only one factor at a time while holding others constant, making it impossible to identify these crucial interactions that are often key to method robustness and understanding complex systems [30] [31].

How can I ensure my DoE meets regulatory requirements?

Answer: DoE is a cornerstone of Quality by Design (QbD) principles emphasized by regulatory bodies:

- Documentation: Thoroughly document your DoE matrix, statistical analysis, and final optimized method parameters [30].

- Design Space: Use DoE to define and demonstrate your method's "design space"—the multidimensional combination of input variables that provide assurance of quality [30].

- Robustness: Systematically identify factor interactions that affect method robustness, creating methods less susceptible to minor environmental variations [30] [31].

Quantitative Data Tables

Comparison of Common DoE Designs for Parameter Optimization

Table 1: Key characteristics of experimental designs for different optimization stages

| Design Type | Primary Purpose | Factors Typically Handled | Runs Required | Key Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full Factorial | Complete understanding of all effects & interactions | 2-5 factors | 2^k (k=factors) | Identifies all main effects & interactions | Number of runs grows exponentially with factors |

| Fractional Factorial | Screening many factors efficiently | 5+ factors | 2^(k-p) (reduced runs) | Dramatically reduces experiments while identifying vital factors | Confounds (aliases) some interactions |

| Plackett-Burman | Screening very large numbers of factors | 10+ factors | Multiple of 4 | Highly efficient for main effects screening | Cannot study interactions |

| Response Surface Methodology (RSM) | Optimization & finding "sweet spot" | 2-4 critical factors | Varies (e.g., 13-30) | Models curvature & finds optimal conditions | Requires prior knowledge of critical factors |

| Definitive Screening | Screening with curvature detection | 6+ factors | 2k+1 (efficient) | Handles many factors, detects curvature, straightforward analysis | Limited ability to model complex interactions |

Statistical Sampling Guidelines for DoE Validation

Table 2: Recommended sample sizes for validating DoE results based on failure rates

| Observed Failure Rate | Minimum Validation Sample Size | Confidence Level | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1% | 300 units | 95% (α=0.05) | Requires large sample for rare events |

| 5% | 60 units | 95% (α=0.05) | Practical for moderate failure rates |

| 10% | 30 units | 95% (α=0.05) | Common benchmark for validation |

| 15% | 20 units | 95% (α=0.05) | Efficient for higher failure processes |

| 20% | 15 units | 95% (α=0.05) | Rapid validation of improvements |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Screening DoE for Initial Factor Identification

Purpose: Efficiently identify the most influential factors among many potential variables.

Methodology:

- Define Problem: Clearly state the analytical method being optimized and key performance indicators (resolution, peak shape, sensitivity) [30].

- Select Factors: Brainstorm with subject matter experts to identify all potential input variables [31]. Include any variable that could influence method performance [30].

- Choose Design: Select fractional factorial or Plackett-Burman design based on factor number and resource constraints [30].

- Set Levels: For continuous factors, choose low and high levels as far apart as reasonably possible [29].

- Randomize Execution: Run experiments in randomized order to minimize bias from lurking variables [30].

- Analyze Results: Use ANOVA to identify statistically significant factors (typically p<0.05). Focus on factors with largest main effects [31].

Validation: Confirm identified critical factors align with theoretical understanding of the analytical chemistry involved [30].

Protocol 2: Response Surface Methodology for Parameter Optimization

Purpose: Find optimal parameter settings and understand response curvature.

Methodology:

- Input Critical Factors: Use 2-4 factors identified from screening experiments [30].

- Select RSM Design: Choose Central Composite or Box-Behnken design based on factor number and region of interest [30].

- Set Levels: Typically 3-5 levels per factor to model curvature [30].

- Execute Design: Run all experimental points in randomized order [30].

- Model Development: Fit quadratic model to data: Y = β₀ + ΣβᵢXᵢ + ΣβᵢᵢXᵢ² + ΣβᵢⱼXᵢXⱼ

- Optimization: Use contour plots and desirability functions to identify optimal factor settings [30].

- Validation: Perform confirmatory runs at predicted optimal conditions to verify model accuracy [31].

Workflow Visualization

DoE Parameter Optimization Workflow

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential tools for successful DoE implementation in analytical method optimization

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Statistical Software | Minitab, JMP, Design-Expert, MODDE | Experimental design creation, data analysis, visualization | Essential for efficient design generation and complex statistical analysis [31] |

| Automation Systems | Automated liquid handlers, robotic sample processors | Precise factor level adjustment, reduced human error | Critical for high-throughput screening and reproducible factor level implementation |

| Data Management | Electronic Lab Notebooks (ELNs), LIMS | Robust data collection, version control, documentation | Prevents data loss and ensures audit trail for regulatory compliance [31] |

| Analysis Instruments | HPLC, GC-MS, Spectrophotometers | Response measurement with precision and accuracy | Quality of response data directly impacts DoE success and model accuracy |

| Design Templates | 2^k factorial, Central Composite, Box-Behnken | Standardized starting points for common scenarios | Accelerates design phase; especially useful for DoE beginners [30] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the key differences between gradient-based and population-based optimization methods, and when should I choose one over the other?

Gradient-based methods use derivative information for precise, efficient optimization in continuous, differentiable problems. In contrast, population-based metaheuristics use stochastic search strategies, making them suitable for complex, non-convex, or non-differentiable problems where derivative information is unavailable or insufficient [33]. Choose gradient-based methods for data-rich scenarios requiring rapid convergence in smooth parameter spaces. Choose population-based algorithms for problems with multiple local optima, discrete variables, or complex, noisy landscapes [33] [34].

FAQ 2: How can sensitivity analysis improve my optimization process in analytical method development?

Sensitivity analysis systematically evaluates how changes in input parameters affect your model outputs, helping you identify critical parameters and assess model robustness [35]. In optimization, this helps determine the stability of optimal solutions under parameter perturbations, guides parameter tuning in metaheuristic algorithms, and supports scenario analysis [35]. This is particularly valuable for understanding the impact of factors like reactant concentration, pH, and detector wavelength in analytical methods [36].

FAQ 3: My hybrid metaheuristic-ML model is not converging well. What are the primary factors I should investigate?

First, examine your hyperparameter tuning strategy. Many hybrid frameworks use optimizers like Grey Wolf Optimizer (GWO), Whale Optimization Algorithm (WOA), or Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) to dynamically tune ML model hyperparameters [37]. Second, ensure your training dataset is sufficiently large and representative - as a rule of thumb, datasets should ideally comprise at least 30 times more samples than the number of trainable parameters [37]. Finally, consider algorithm selection carefully, as certain optimizers show target-specific performance improvements [37].

FAQ 4: What software tools are available for implementing sensitivity analysis in optimization workflows?

- Spreadsheet-based tools like Microsoft Excel offer Data Tables, Goal Seek, and Scenario Manager for small to medium-scale problems [35].

- Python libraries like SALib provide a wide range of sensitivity analysis methods and integrate well with optimization algorithms [35].

- Specialized software like SimLab (open-source) implements various sampling methods and sensitivity indices, while DAKOTA offers comprehensive optimization and uncertainty quantification toolkit [35].

Troubleshooting Guides

Poor Convergence in Metaheuristic Algorithms

Problem: Your nature-inspired optimization algorithm (PSO, GA, GWO) is converging slowly, stagnating at local optima, or failing to find satisfactory solutions.

Diagnosis and Resolution:

Check Parameter Settings

- Symptoms: Rapid premature convergence or excessive wandering.

- Solution: Adjust population size, iteration limits, and algorithm-specific parameters. For PSO, optimize inertia weight and acceleration coefficients; for GA, fine-tune mutation and crossover rates [34].

Verify Objective Function

- Symptoms: Algorithm progresses but fails to improve solution quality meaningfully.

- Solution: Ensure your objective function correctly captures the problem goals. Check for flat regions or discontinuities that might hinder progress [34].

Address Exploration-Exploitation Balance

- Symptoms: Algorithm consistently gets stuck in suboptimal local solutions.

- Solution: Increase population diversity or incorporate mechanisms like simulated annealing's temporary acceptance of worse solutions to escape local optima [34].

Consider Hybrid Approaches

- Symptoms: Standard algorithms fail to meet performance requirements.

- Solution: Implement hybrid models that combine metaheuristics with machine learning. For example, use GWO to optimize XGBoost hyperparameters, which has demonstrated superior performance in complex prediction tasks [37].

Handling High-Dimensional and Multimodal Problems

Problem: Optimization performance degrades significantly as problem dimensionality increases, or the algorithm fails to locate the global optimum in landscapes with multiple local optima.

Diagnosis and Resolution:

Apply Dimensionality Reduction

- Action: Use feature selection or extraction techniques (PCA, autoencoders) to reduce the search space before optimization [33].

Utilize Advanced Algorithms

Conduct Sensitivity Analysis

Leverage Distributed Computing

- Action: Employ parallel processing frameworks (TensorFlow, PyTorch) to distribute computational load across multiple resources [33].

Sensitivity Analysis Inconclusive or Computationally Expensive

Problem: Sensitivity analysis produces unclear results about parameter importance, or the computational cost is prohibitive for your resources.

Diagnosis and Resolution:

Choose Appropriate Method

- Situation: Need quick screening of influential factors.

- Solution: Use one-at-a-time (OAT) analysis or local methods like differential analysis for initial screening [35].

Situation: Require comprehensive understanding of parameter interactions.

Optimize Experimental Design

- Action: Replace full factorial designs with fractional factorial or space-filling designs like Latin Hypercube Sampling to reduce required runs while maintaining representativeness [39].

Employ Efficient Sampling

- Action: Use advanced sampling techniques such as Latin Hypercube Sampling (LHS) to achieve better spatial distribution uniformity with fewer samples [39].

Apply Sensitivity Visualization

- Action: Visualize results with tornado diagrams for ranking parameter influences or spider plots to understand interaction effects [35].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Essential Computational Tools for Optimization and Sensitivity Analysis

| Tool Name | Type/Category | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| TensorFlow(v2.10+) [33] | Framework/Library | Provides automatic differentiation and distributed training support for gradient-based optimization. |

| PyTorch(v2.1.0+) [33] | Framework/Library | Enables dynamic computation graphs and GPU-accelerated model training for ML-driven optimization. |