Portable vs. Laboratory Instruments in 2025: A Performance Comparison for Research and Diagnostics

This article provides a comprehensive performance comparison between portable and laboratory instruments for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Portable vs. Laboratory Instruments in 2025: A Performance Comparison for Research and Diagnostics

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive performance comparison between portable and laboratory instruments for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational capabilities and limitations of portable devices, details their methodological applications across biomedical and clinical settings, offers troubleshooting and optimization strategies for field deployment, and presents a framework for validation and comparative analysis against traditional lab equipment. The synthesis of these four intents delivers actionable insights for selecting the right tool to enhance efficiency, data integrity, and innovation in scientific research.

Defining the Modern Lab: Capabilities and Trade-offs of Portable vs. Benchtop Systems

In the landscape of scientific research, the line between portable and laboratory-grade instrumentation is increasingly blurred. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, understanding the precise definition and capabilities of "portable" equipment in 2025 is critical for making informed decisions in field analysis, process monitoring, and decentralized laboratories.

A portable analytical instrument is a compact, mobile device designed for on-site detection and measurement of analytes, providing immediate results without the need for sample transportation to a fixed laboratory [1]. By 2025, this definition encompasses devices that are not only physically transportable but also integrated with advanced data connectivity, maintain performance standards approaching those of traditional lab equipment, and are designed for use in diverse—and often harsh—environments by operators with varying skill levels [2] [3] [4].

Defining the 2025 Portable Instrument

The core characteristics of a portable instrument extend beyond mere mobility. The following table summarizes the multi-faceted definition based on current technological and market trends.

Table 1: Core Defining Characteristics of Portable Analytical Instruments in 2025

| Characteristic | 2025 Definition and Standards |

|---|---|

| Physical Attributes | Low weight, small dimensions, and ruggedized design capable of withstanding harsh environments (e.g., high humidity, extreme temperatures, dust) [2]. |

| Performance Metrics | Designed to generate data similar to laboratory-acquired results, though often with moderately higher detection limits and lower sensitivity than stationary counterparts [2]. |

| Operational Infrastructure | Operates on simple infrastructure with a portable energy source (e.g., batteries), minimal or no reagent use, and little to no analytical waste [2]. |

| Data Connectivity | Integrated wireless communication (IoT), cloud data storage, and real-time monitoring capabilities, often with mobile app integration [3] [4]. |

| User Interface (UI) | Emphasis on usability engineering and intuitive design, with software integration for data management and analysis [5] [4]. |

Performance Comparison: Portable vs. Laboratory Instruments

The choice between portable and laboratory-based analysis involves trade-offs. Portable instruments excel in speed, cost-effectiveness for on-site use, and providing immediate decision-making data, while lab instruments remain the gold standard for utmost precision and comprehensive analysis [1].

Table 2: Performance and Operational Comparison: Portable vs. Laboratory Instruments

| Aspect | Portable Instruments | Laboratory Instruments |

|---|---|---|

| Accuracy & Precision | High effectiveness, but may not match the ultimate precision of lab-based equipment [1]. | Higher accuracy and precision in controlled environments [1]. |

| Testing Range & Sensitivity | May have a restricted testing range and higher detection limits [1] [2]. | Comprehensive data from a wider range of tests with superior sensitivity [1]. |

| Analysis Speed & Cost | Immediate results; reduces transportation and lab fees [1]. | Time-consuming process leading to higher costs [1]. |

| Operational Flexibility | Highly versatile for use in remote locations and industrial sites [1]. | Inflexible; requires samples to be sent to a specific location [1]. |

| Data Management | Real-time data streaming, cloud storage, and mobile integration [3] [4]. | Centralized data management on institutional systems, often requiring manual transfer. |

| Key Applications | On-site screening, emergency response, process monitoring, environmental field studies [1] [2]. | Regulatory compliance, method development, research requiring ultimate data comprehensiveness [1]. |

Supporting Experimental Data: A Field Comparison Study

A 2015 field study published in Atmospheric Environment provides a model for the type of validation essential for portable instruments, comparing them against stationary reference instruments for outdoor air exposure assessment [6].

Experimental Protocol:

- Objective: To validate the performance of portable monitors (

micro-aethalometer AE51,DiscMini,Dusttrak DRX) for assessing outdoor air pollution in an urban environment [6]. - Parameters Measured: Black carbon (BC), particle number concentration (N), alveolar lung-deposited surface area (LDSA), mean particle diameter, PM10, PM2.5, and PM1 [6].

- Methodology: The portable monitors were compared against widely used, high-quality stationary instruments (

MAAP,CPC,SMPS,NSAM,GRIMM aerosol spectrometer) collocated in the same field environment. The study assessed agreement using R² values and relative differences between the instrument types [6]. - Key Findings: The results demonstrated a good agreement between most portable and stationary instruments, with R² values mostly >0.80. The relative differences between portable and stationary instruments were mostly <20%, and the variation between different units of the same portable instrument was <10% [6]. This validates portable monitors as effective "indicative instruments" for field exposure assessment studies.

The Scientist's Toolkit for Portable Analysis

Effectively deploying portable instruments requires a suite of supporting tools and reagents. The selection is critical for ensuring data quality and operational efficiency in the field.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Field Analysis

| Item / Solution | Function in Field Analysis |

|---|---|

| Calibration Standards | Essential for ensuring accuracy; portable instruments require regular, on-site calibration to maintain reliability, traceable to reference materials [4]. |

| Sensor/Spectrum Cleaning Kits | Used for maintenance of optical surfaces and sensors to prevent contamination and ensure signal integrity during on-site measurements [2]. |

| Portable Power Solutions | High-capacity batteries or portable power packs are crucial for uninterrupted operation in remote locations lacking reliable electricity [2] [3]. |

| Stabilization & Preservation Reagents | For stabilizing liquid samples (e.g., water, biological fluids) prior to on-site analysis to prevent analyte degradation during transport or short-term storage. |

| Sample Introduction Kits | Disposable, ready-to-use kits for consistent sample handling (e.g., syringes, vials, solid-phase microextraction fibers) to minimize handling errors [4]. |

A Decision Framework for Instrument Selection

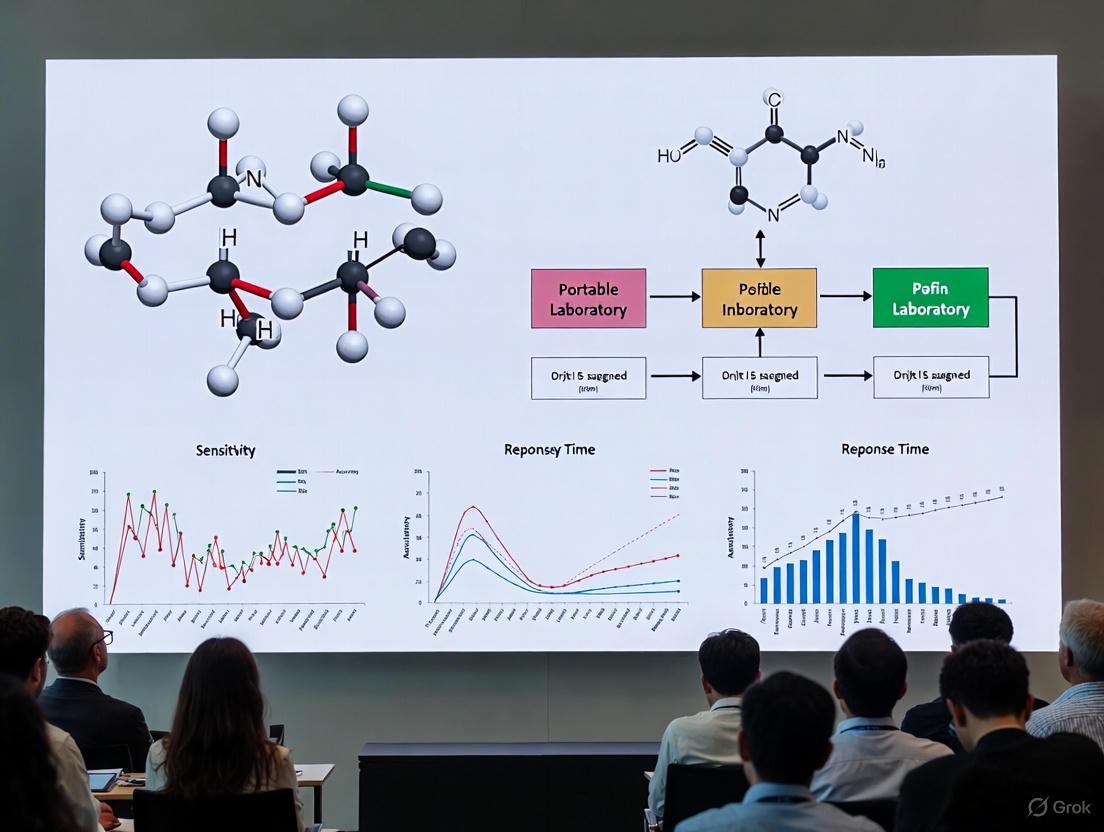

Choosing between portable and laboratory instrumentation is a multi-factorial decision. The following diagram maps out the core decision-making workflow for researchers.

The portable analytical instruments market, valued at over USD 15 billion in 2023 and projected to reach USD 30.62 billion by 2032 (CAGR of 7.98%), is a testament to its growing importance [3]. Key trends shaping its future include the rise of Real-Time Release Testing (RTRT) in pharmaceutical manufacturing, which uses in-process portable methods to reduce batch release times [7], and the critical integration of usability engineering to minimize use errors, a mandatory process for medical device approval that is becoming a best practice across all portable instrument categories [5].

Conclusion: In 2025, a "portable" instrument is defined by a synergy of mobility, connected intelligence, and rugged reliability. While laboratory systems remain indispensable for the most exhaustive analyses, portable instruments have firmly established their role in providing rapid, cost-effective, and decision-grade data at the point of need. For the modern researcher, the choice is no longer a question of superiority but of strategic alignment with the project's specific requirements for speed, precision, and context.

The Analytical Balance: Portable vs. Laboratory Instruments

The choice between portable and laboratory-based instruments is a fundamental consideration in modern research and drug development. This decision often hinges on a careful analysis of key performance metrics: throughput, accuracy, and precision. While portable devices offer the advantage of real-time, on-site analysis, enabling rapid decision-making in the field, lab-based equipment typically provides superior precision and comprehensive data in a controlled environment [1].

The evolution of portable technologies is narrowing this performance gap. Recent advancements include portable molecular diagnostic platforms that deliver high sensitivity and specificity for detecting pathogens like mpox, and low-cost, portable PCR devices that bring powerful molecular biology techniques to resource-limited settings [8] [9]. This guide provides an objective comparison of these analytical alternatives, supported by experimental data and detailed methodologies.

Performance Metrics at a Glance

The following tables summarize the quantitative performance characteristics of portable and laboratory instruments across different application domains.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Diagnostic Platforms for Pathogen Detection

| Metric | Portable Dragonfly Platform (LAMP) | Laboratory qPCR (Gold Standard) |

|---|---|---|

| Application | Mpox virus detection | Mpox virus detection |

| Sensitivity | 94.1% (for MPXV) | Used as reference |

| Specificity | 100% (for MPXV) | Used as reference |

| Time-to-Result | < 40 minutes | Several hours (includes transport) |

| Throughput | Lower; designed for single or few samples | Higher; capable of batch processing |

| Footprint | Portable, compact | Benchtop, requires lab infrastructure |

Source: Clinical validation on 164 samples, including 51 mpox-positive cases [8].

Table 2: Performance and Cost Analysis of Portable vs. Laboratory PCR Systems

| Metric | Portable Low-Cost PCR Device | Conventional Commercial PCR Instrument |

|---|---|---|

| Temperature Accuracy | ± 0.55 °C | Typically higher [9] |

| Heating/Cooling Rate | 1.78 °C/s & 1.52 °C/s | Varies, often faster |

| Footprint & Portability | 210 × 140 × 105 mm³, 670 g, portable | Bulky, stationary |

| Power Source | Power bank | Mains electricity |

| Cost | Low-cost, open-source design | Prohibitively expensive |

| Result Quality | Comparable amplification success | Gold-standard results |

Source: Validation experiments amplifying kelp genes [9].

Table 3: Operational Pros and Cons of Portable vs. Lab-Based Analysis

| Aspect | Portable Analysis | Laboratory Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Throughput | Lower; suited for immediate, on-site tests | Higher; optimized for processing large batches |

| Accuracy & Precision | High and effective for many applications, but may not match lab-level precision [1] | Higher precision due to controlled conditions and advanced equipment [1] |

| Cost & Logistics | More cost-effective; reduces transport and lab fees [1] | Higher costs; involves sample transport, lab fees, and longer timelines [1] |

| Data Comprehensiveness | May have a restricted testing range [1] | Can conduct a wider range of tests for more detailed analysis [1] |

| Operational Environment | Versatile for field use in remote or industrial sites [1] | Limited to a controlled laboratory setting [1] |

Experimental Protocols for Performance Validation

To ensure the reliability of the data presented in the comparisons, rigorous experimental protocols are essential. The following methodologies are derived from the cited research.

Protocol for Clinical Validation of a Portable Molecular Diagnostic Platform

This protocol outlines the procedure used to validate the Dragonfly platform for detecting mpox and other viruses [8].

- Objective: To assess the clinical sensitivity and specificity of the portable Dragonfly platform for detecting orthopoxvirus (OPXV), monkeypox virus (MPXV), varicella-zoster virus (VZV), and herpes simplex virus (HSV) against a gold-standard qPCR workflow.

- Sample Collection: A total of 164 clinical samples were used, including 51 mpox-positive samples. Samples were collected using swabs and placed in an inactivating medium (e.g., COPAN eNAT).

- Nucleic Acid Extraction: The portable, power-free "SmartLid" technology was employed. This method uses a magnetic lid to capture and transfer magnetic beads through lysis-binding, washing, and elution steps. The process was completed in under 5 minutes without the need for centrifuges or pipetting.

- Amplification and Detection: The extracted nucleic acids were added to a lyophilised colourimetric LAMP panel. The isothermal amplification was carried out at a constant temperature (60-65 °C) for less than 35 minutes. Results were determined by a visual colour change from pink (negative) to yellow (positive), facilitated by a pH shift due to DNA amplification.

- Data Analysis: The results from the Dragonfly platform were compared with those from the gold-standard extracted qPCR workflow. Sensitivity and specificity were calculated based on this comparison.

Protocol for Technical Validation of a Portable PCR Device

This protocol describes the methodology for evaluating the performance of a custom, low-cost portable PCR device [9].

- Objective: To validate the thermal performance and functional efficacy of a portable, low-cost PCR device against conventional commercial instruments.

- Thermal Performance Testing: The device's heating block was equipped with a temperature sensor. The system's temperature accuracy and stability were assessed by measuring the heating and cooling rates and the deviation from set-point temperatures during cycling. A piecewise variable coefficient PID algorithm, controlled by an Arduino UNO platform, was used for temperature regulation.

- Functional Testing - DNA Amplification: The practical functionality was tested by amplifying a specific target (kelp genes) using the prototype device. The same reaction was run in a conventional commercial PCR instrument for comparison.

- Result Analysis: The amplification products from both devices were analyzed using standard methods like gel electrophoresis. The success of the amplification and the quality of the results from the portable device were compared to those from the commercial instrument to verify comparable performance.

Workflow and Decision-Making Diagrams

The diagrams below illustrate the experimental workflow for portable device validation and the logical process for selecting between portable and lab-based instruments.

Experimental Workflow for Validating a Portable Molecular Diagnostic Platform [8]

Decision Workflow for Selecting Analytical Instrument Type [1]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The successful implementation of portable analytical methods, particularly in molecular diagnostics, relies on a suite of specialized reagents and materials.

Table 4: Essential Reagents and Materials for Portable Molecular Diagnostics

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| Lyophilised Colourimetric LAMP Mix | A stable, room-temperature master mix containing enzymes, nucleotides, and primers for isothermal amplification, with a pH indicator for visual detection [8]. |

| Magnetic Beads for Nucleic Acid Extraction | Superparamagnetic nanoparticles that bind nucleic acids, enabling their purification and separation from other sample components using a magnet, without power or centrifugation [8]. |

| Sample Collection Kit (Swab & Inactivating Medium) | Used for safe and stable collection and transport of clinical specimens (e.g., from lesions). The medium inactivates the virus to ensure user safety [8]. |

| Portable Isothermal Heat Block | A compact, low-power device that maintains a constant temperature (e.g., 60-65°C) required for LAMP reactions, replacing bulky thermocyclers [8]. |

| Arduino-based Controller | An open-source electronics platform used in low-cost portable instruments (e.g., PCR machines) to precisely control temperature and other hardware functions [9]. |

The comparative analysis of performance metrics reveals a clear, application-dependent rationale for choosing between portable and laboratory instruments. Portable analytical devices have achieved a level of accuracy and precision that makes them viable for a wide range of field-based applications, from clinical diagnostics to environmental monitoring, without sacrificing speed and cost-effectiveness [1] [8].

For researchers and drug development professionals, the optimal strategy is not an exclusive choice but a synergistic one. Leveraging portable devices for rapid, on-site screening and initial assessments, while relying on laboratory instruments for ultimate validation and highly complex analyses, creates a powerful, integrated analytical framework. This approach, guided by a clear understanding of the inherent trade-offs in throughput, accuracy, and precision, maximizes efficiency and data quality throughout the research and development lifecycle.

The choice between portable and laboratory-based analytical instruments is a critical consideration for researchers and drug development professionals. This decision hinges on a fundamental trade-off: the operational flexibility and immediate data access of portable tools versus the supreme accuracy and comprehensive data provided by traditional lab systems. Driven by advances in miniaturization, sensor technology, and connectivity, portable instruments are carving out a significant role in modern laboratories, particularly in the fast-paced pharmaceutical industry which is increasingly embracing the automated, digital "Lab of the Future" [10]. This guide provides an objective performance comparison to help scientists navigate this trade-off, supported by experimental data and detailed protocols.

Fundamental Concepts and Definitions

What is Portable Analysis?

Portable analysis involves the use of compact, mobile devices to detect and measure elements directly on-site [1]. These instruments are designed for fieldwork, providing immediate results without the need for sample transportation to a central lab. Their portability enables real-time analysis and on-the-spot decision-making, which is ideal for remote environments, emergency response, and in-process checks in manufacturing [1] [2].

What is Lab-Based Analysis?

Lab-based analysis involves examining samples within a controlled laboratory environment using advanced, stationary equipment [1]. This setting allows for highly detailed and comprehensive analysis, offering the highest levels of accuracy and precision. The process, however, often involves longer turnaround times due to sample preparation, transport, and queuing [1] [11].

The Emergence of Total Laboratory Automation (TLA)

The concept of the static laboratory is evolving. Total Laboratory Automation (TLA) represents a transformative approach in clinical and analytical laboratories, integrating advanced technologies across pre-analytical, analytical, and post-analytical phases [11]. TLA leverages robotics, conveyor tracks, and sophisticated middleware to streamline workflows, reduce manual intervention, and enhance quality control. This evolution blurs the lines, as future labs may function as distributed networks of smart, connected devices, with portable tools playing a key role [11] [10].

Comparative Analysis: Portable vs. Laboratory Instruments

The decision between portable and lab-based analysis is not about finding a universal "best" option, but rather identifying the right tool for a specific purpose. The table below summarizes the inherent advantages and limitations of each approach.

Table 1: Core Advantages and Limitations of Portable and Laboratory Instruments

| Feature | Portable Instruments | Laboratory Instruments |

|---|---|---|

| Speed & Efficiency | Real-time, immediate results enabling on-the-spot decisions [1] [12]. | Longer turnaround times due to sample transport and processing delays [1]. |

| Operational Costs | Cost-effective for on-site use; reduces transport and lab fees [1] [12]. | Higher operational costs due to equipment, technician time, and transport [1]. |

| Data Accuracy & Precision | Good, but generally lower precision than lab equipment; more susceptible to environmental factors [1] [2]. | Very high accuracy and precision in a controlled environment with advanced equipment [1] [11]. |

| Scope of Analysis | Limited testing range; focused analysis for specific applications [1]. | Comprehensive data; capable of a wider range of tests and more detailed analysis [1]. |

| Flexibility & Use Case | Highly versatile for field use, remote locations, and rapid screening [1] [2]. | Inflexible; requires samples to be brought to a specific, fixed location [1]. |

| Environmental Impact | Greener operations; often reagent-free, less waste, lower energy consumption [2] [12]. | Higher resource consumption; typically uses more reagents and generates more waste [2]. |

Performance Comparison: Experimental Data and Protocols

To move beyond theoretical comparisons, controlled experiments are essential. The following section details a specific study comparing the performance of portable aerosol instruments to a laboratory reference standard.

Experimental Protocol: Evaluating Portable Aerosol Monitors

A study published in Annals of Work Exposures and Health provides a robust methodology for comparing field-portable instruments against a laboratory benchmark [13]. The research aimed to evaluate the performance of portable devices for measuring airborne nanoparticle concentrations and size distributions, which is critical for occupational health assessments in nanotechnology and pharmaceutical settings.

1. Research Objective: To evaluate the performance of portable aerosol instruments (Handheld CPC, PAMS, NanoScan SMPS) by comparing their measurements of particle concentration and size distribution to those from a reference laboratory Scanning Mobility Particle Sizer (SMPS) [13].

2. Materials and Reagents: Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions and Key Materials

| Item Name | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| Sodium Chloride (NaCl) Solution | A 0.2% solution in distilled water was used to generate stable, polydispersed test aerosols via an atomizer [13]. |

| Six-Jet Atomizer | Generates a fine mist of the NaCl solution, creating a consistent source of polydispersed aerosol particles for testing [13]. |

| Diffusion Dryer | Removes moisture from the generated aerosol stream, ensuring dry particle measurements [13]. |

| Kr-85 Aerosol Neutralizer | Conditions the aerosols with a known charge distribution, essential for accurate size classification in the Differential Mobility Analyzer (DMA) [13]. |

| Electrostatic Classifier & DMA | The core of the reference SMPS; classifies polydispersed aerosols into precise, monodispersed sizes based on electrical mobility [13]. |

| 9000-L Testing Chamber | A large, sealed environment for mixing and stabilizing polydispersed aerosols at controlled concentrations before classification [13]. |

| 5-L Sampling Chamber | A smaller chamber where classified monodispersed aerosols are presented to the portable instruments and reference SMPS for simultaneous measurement [13]. |

3. Methodology: The experimental workflow was designed in three key stages, as illustrated below.

Diagram 1: Aerosol Instrument Test Workflow

4. Key Quantitative Results: The performance of the portable instruments was quantified by the deviation of their readings from the reference laboratory SMPS.

Table 3: Performance Comparison of Portable vs. Laboratory Aerosol Instruments [13]

| Instrument Type | Particle Concentration Deviation (Monodispersed Aerosol) | Particle Concentration Deviation (Polydispersed Aerosol) | Particle Size Deviation (Polydispersed Aerosol) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reference Laboratory SMPS | Baseline | Baseline | Baseline |

| NanoScan SMPS (Portable) | Within 13% of reference | Within 10% of reference | ≤ 4% |

| PAMS (Portable) | Within 25% of reference | Within 36% of reference | Within 10% |

| Handheld CPC (Portable) | Within 30% of reference | Data Not Provided | Data Not Provided |

This data clearly demonstrates the inherent performance trade-off. While portable instruments like the NanoScan SMPS can provide remarkably good agreement with lab equipment (within 10-13% for concentration), the laboratory-based SMPS remains the benchmark for ultimate precision. The choice in a real-world setting would depend on whether the application requires the highest possible accuracy (favoring the lab) or the ability to make rapid, on-site decisions with good reliability (favoring the portable tool).

Decision Framework and Future Trends

Selecting the Right Tool for the Need

The following diagram outlines a logical decision pathway to guide researchers in selecting between portable and laboratory instruments.

Diagram 2: Instrument Selection Decision Pathway

The Future Laboratory: Integration and Intelligence

The distinction between portable and laboratory instruments is becoming more fluid. The "Lab of the Future" is envisioned as a highly efficient, intelligent, and connected space [10]. Key trends include:

- AI and Machine Learning: These technologies are being integrated to handle complex datasets from automated systems, providing predictive analytics and decision support, ultimately accelerating discovery cycles [11] [10].

- Collaborative Robotics (Cobots): Cobots like ABB's GoFa are being deployed to automate repetitive, ergonomically challenging tasks such as pipetting and powder dispensing. This enhances reproducibility, frees up scientists for higher-value work, and enables "lights off" automation [14].

- Strategic Partnerships: Companies like ABB, Mettler Toledo, and Agilent are collaborating to create integrated ecosystems of lab automation, making sophisticated robotics more accessible and validated for pharmaceutical workflows [14].

The portability trade-off is a fundamental aspect of modern scientific research. Portable analytical instruments offer unmatched speed, flexibility, and cost-efficiency for on-site analysis, while traditional laboratory systems provide unrivaled accuracy and comprehensiveness. The experimental data confirms that while the performance gap can be narrow in some cases, a measurable difference exists. For researchers and drug development professionals, the optimal strategy is not a binary choice but a pragmatic one: use portable devices for rapid screening and real-time decision-making, and rely on laboratory instruments for definitive, high-precision analysis. As the industry moves toward the connected, automated Lab of the Future, the intelligent integration of both portable and stationary systems will be key to driving efficiency, innovation, and ultimately, better patient outcomes.

The clinical diagnostics landscape is undergoing a transformative shift, moving from centralized laboratory testing to decentralized, immediate point-of-care solutions. This evolution is driven by technological advancement, growing clinical demand for rapid results, and changing healthcare delivery models. Point-of-care testing (POCT) brings laboratory capabilities directly to patients—whether in hospital bedsides, clinics, remote locations, or even homes—enabling real-time clinical decision-making [1] [15]. Meanwhile, traditional laboratory analyzers continue to advance, offering unparalleled precision for complex testing protocols. This creates a critical dichotomy in modern healthcare: the choice between the immediacy of portable instruments and the comprehensive accuracy of centralized laboratory systems [1].

This guide objectively compares the performance of portable versus laboratory instruments within the broader thesis of diagnostic device evolution. We examine quantitative performance data, detailed experimental methodologies, and the technical specifications that define the capabilities and limitations of each approach. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, understanding this evolving landscape is essential for selecting appropriate testing methodologies, developing new diagnostic solutions, and integrating these technologies into next-generation healthcare frameworks where both centralized and decentralized models coexist and complement one another [16].

Market Growth Drivers and Quantitative Trends

The diagnostic market is experiencing significant expansion, with both laboratory and point-of-care segments demonstrating robust growth propelled by distinct yet interconnected factors.

Market Size and Projections

The global point-of-care testing market exemplifies this rapid growth, with its value expected to increase from USD 44.7 billion in 2025 to USD 82 billion by 2034, representing a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 7% [17]. Similarly, the portable laboratory market specifically is projected to reach $1,358.2 million in 2025, maintaining a CAGR of 9.2% through 2033 [18]. This growth substantially outpaces many traditional healthcare sectors, highlighting the accelerating shift toward decentralized testing solutions.

Table 1: Global Market Projections for Diagnostic Testing Segments

| Market Segment | 2024/2025 Market Size | 2033/2034 Projected Market Size | CAGR | Primary Growth Regions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Point-of-Care Testing | USD 44.7 billion (2025) [17] | USD 82 billion (2034) [17] | 7% [17] | North America, Asia-Pacific [17] |

| Portable Laboratory | $1,358.2 million (2025) [18] | - | 9.2% (2025-2033) [18] | North America, Europe, Asia-Pacific [18] |

| STD Diagnostics (U.S.) | USD 5.06 billion (2024) [19] | USD 8.49 billion (2033) [19] | 5.91% [19] | California, Texas, New York, Florida [19] |

Key Growth Catalysts

Several interconnected factors are propelling this market evolution. The rising prevalence of chronic and infectious diseases continues to drive demand for accessible and rapid diagnostic solutions, particularly in developing countries where healthcare infrastructure may be limited [17]. Communicable diseases such as HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, and malaria remain leading causes of death and disability in low-income populations, creating urgent need for deployable testing solutions [17].

Technological advancements represent another critical driver, with innovations in miniaturization, microfluidics, biosensors, and artificial intelligence enabling the development of more accurate, portable, and user-friendly POCT devices [17] [15]. These innovations have transformed complex laboratory processes into compact, automated systems capable of delivering laboratory-grade results in non-laboratory settings [15].

Furthermore, increased research and development investment from both public and private sectors continues to accelerate innovation. For instance, the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) allocated over USD 1.5 billion toward diagnostic technologies, including POCT, reflecting the strategic priority placed on advancing these solutions [17]. This sustained investment is essential for developing diagnostics that are faster, more accurate, and widely available, particularly in underserved regions [17].

Performance Comparison: Portable vs. Laboratory Instruments

Objective performance comparison reveals a nuanced landscape where each testing modality offers distinct advantages depending on clinical context, testing requirements, and operational constraints.

Comparative Analysis of Operational Characteristics

Table 2: Operational Comparison of Portable vs. Laboratory Analysis [1]

| Characteristic | Portable Analysis | Laboratory Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Result Time | Immediate (minutes) | Hours to days |

| Cost Structure | Lower operational cost; reduces sample transport and lab fees | Higher equipment and technician costs |

| Accuracy/Precision | Effective but may not match lab precision in all scenarios [20] [21] | Higher precision in controlled environments |

| Testing Range | Limited menu of available tests | Comprehensive testing capabilities |

| Operational Requirements | Potential for operator error; influenced by field conditions | Standardized processes with trained professionals |

| Flexibility | Highly versatile for various environments and remote locations | Inflexible; requires samples be transported to lab |

| Data Comprehensiveness | Focused results for immediate decision-making | Detailed analysis with expert interpretation |

Experimental Evidence and Performance Data

Clinical studies provide quantitative evidence regarding the performance relationship between portable and laboratory instruments. A 2018 prospective comparison of point-of-care and standard laboratory analyzers for monitoring International Normalized Ratio (INR) in anticoagulated patients demonstrated excellent correlation between the CoaguChek XS Pro POCT device and the Sysmex CS2000i laboratory analyzer (correlation coefficient = 0.973) [20]. However, the study revealed a consistent positive bias in the POCT device, with a mean difference of 0.21 INR, which increased at higher INR values: 0.09 in subtherapeutic range (≤1.9 INR), 0.29 INR in therapeutic range (2.0-3.0 INR), and 0.4 INR in supratherapeutic range (>3.0 INR) [20]. This systematic variation, while not affecting most clinical decisions, highlights the importance of understanding device-specific performance characteristics, particularly at clinically critical thresholds.

Similarly, a large-scale 2022 verification study of POCT blood glucose meters revealed important considerations for portable device performance. The study of 64 Accu-Chek Inform II POCT meters found that 58 (90.6%) met accuracy requirements compared to laboratory biochemical analyzers [21]. However, performance variation was concentration-dependent, with qualification rates declining as glucose concentrations increased, demonstrating how analytical performance can be analyte- and context-specific [21]. The study also identified specific interfering substances, noting that iodophor disinfectant significantly skewed glucose measurements, highlighting the importance of standardized operating procedures for POCT devices [21].

Glucose Meter Validation Workflow

Technological Innovations Shaping Both Segments

Both portable and laboratory diagnostic segments are benefiting from convergent technological trends that are reshaping their capabilities and applications.

Laboratory Analyzer Advancements

Traditional laboratory systems continue to evolve, with automation playing an increasingly central role in enhancing efficiency and reducing human error. Modern laboratory analyzers now routinely handle tasks like barcoding, decapping, sorting, and aliquoting samples, freeing skilled technicians for higher-value activities [16]. The Internet of Medical Things (IoMT) is transforming laboratory connectivity, enabling instruments, robots, and "smart" consumables to communicate seamlessly, creating integrated workflows that enhance both efficiency and traceability [16].

Mass spectrometry technology is becoming more accessible and affordable for clinical laboratories, with the global market expected to grow from approximately USD 6.93 billion in 2023 to USD 8.17 billion by 2025 [16]. This technology enables more accurate analysis for specific clinical applications, particularly in proteomics and metabolic studies, potentially revolutionizing diagnosis and disease management through advancements in personalized medicine [16].

Point-of-Care Technology Innovations

Portable diagnostics are undergoing revolutionary changes driven by miniaturization and connectivity. Complex laboratory equipment is being condensed into compact, handheld devices through innovations in microfluidics and lab-on-a-chip systems that handle minute biological samples within small cartridges [17] [15]. These integrated systems combine sample preparation, reaction, and detection in single units, drastically reducing the time and space needed for diagnostics [17].

Modern POCT increasingly incorporates advanced biosensors and artificial intelligence algorithms to improve diagnostic accuracy and reliability [17]. Biosensors based on nanomaterials or electrochemical detection can identify biomarkers at extremely low concentrations, enhancing sensitivity, while AI-driven interpretation helps reduce human error and supports clinical decision-making [17]. Additionally, connectivity features like Bluetooth and Wi-Fi allow POCT devices to sync with electronic health records or send results directly to clinicians, proving particularly valuable in remote or rural areas where specialist access is limited [17] [16].

Diagnostic Technology Evolution Pathway

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Robust experimental protocols are essential for validating diagnostic device performance and ensuring reliable results across different testing environments.

Protocol 1: Method Comparison Study

Objective: To evaluate the agreement between point-of-care and laboratory instruments for specific analyte testing [20] [21].

Materials and Equipment:

- POCT device (e.g., CoaguChek XS Pro for INR; Accu-Chek Inform II for glucose)

- Reference laboratory analyzer (e.g., Sysmex CS2000i for INR; Hitachi 008AS for glucose)

- Appropriate test strips/cartridges and reagents for both systems

- Patient samples (venous/arterial/capillary blood depending on study design)

- Standardized collection tubes (heparin anticoagulant for glucose studies)

Procedure:

- Collect paired samples from participants (n=200 provides statistical power) [20]

- Perform testing with POCT device immediately according to manufacturer instructions

- Transport second sample to laboratory for analysis with reference method within 30 minutes to minimize glycolysis effects [21]

- Ensure both systems undergo proper quality control procedures before testing

- Document all results blindly to prevent observational bias

Statistical Analysis:

- Utilize Passing-Bablok regression analysis and Bland-Altman plots to assess agreement [20]

- Calculate correlation coefficients, mean differences, and 95% limits of agreement

- Analyze clinical significance by categorizing results according to therapeutic ranges and determining impact on clinical decision-making [20]

Protocol 2: Interference Testing

Objective: To identify potential interferents that affect POCT device performance [21].

Materials and Equipment:

- POCT device and consumables

- Potential interferents (e.g., iodophor, other disinfectants, medications)

- Control samples without interferents

- Dilution equipment for preparing concentration gradients

Procedure:

- Prepare sample with known analyte concentration

- Create dilution series with increasing concentrations of potential interferent (e.g., 1:9, 2:8, 3:7, 4:6, 5:5 ratios of interferent to blood) [21]

- Test each dilution in triplicate using POCT device

- Compare measured results against theoretical calculated values

- Analyze linear relationship across concentration range

Analysis:

- Determine threshold at which interferent significantly affects results

- Calculate percentage variation from expected values

- Establish clinical significance of observed interference

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Diagnostic Device Validation

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Quality Control Solutions | Verify analyzer precision and accuracy; monitor system performance | Daily quality control for POCT glucose meters [21] |

| Heparin Anticoagulant Tubes | Prevent blood coagulation while preserving analytes | Blood gas and glucose comparison studies [21] |

| Standardized Test Strips/Cartridges | React with specific analytes to generate measurable signals | INR testing with CoaguChek XS Pro [20] |

| Interferent Substances | Evaluate test specificity and potential false results | Iodophor interference testing in glucose meters [21] |

| Calibration Standards | Establish reference points for quantitative measurements | Instrument calibration pre-study [21] |

| Disinfectants (e.g., 75% ethanol) | Clean sampling sites without interfering with assays | Preferred over iodophor for glucose testing [21] |

Regulatory Landscape and Quality Considerations

The regulatory environment for diagnostic testing continues to evolve, with significant implications for both portable and laboratory instruments. Recent updates to the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA) regulations that took effect in January 2025 have strengthened standards for point-of-care testing to improve quality outside traditional laboratories [22].

Key regulatory changes include enhanced proficiency testing requirements, particularly for commonly tested analytes like hemoglobin A1C, which is now considered a regulated analyte with specific performance criteria [22]. Additionally, personnel qualifications have been updated, with nursing degrees no longer automatically qualifying as equivalent to biological science degrees for high-complexity testing, though alternative pathways exist [22]. Technical consultant qualifications now place greater emphasis on education and professional experience, requiring specific degrees or equivalent combinations of education and training [22].

These regulatory developments highlight the increasing scrutiny on all testing environments and reflect efforts to ensure that decentralized testing maintains reliability standards comparable to traditional laboratories. For researchers and developers, understanding these regulatory trends is essential for designing validation studies and developing compliant diagnostic solutions.

The diagnostic testing landscape continues to evolve toward a hybrid model that leverages the complementary strengths of both portable and laboratory-based testing modalities. Portable instruments excel in scenarios requiring immediate results, decentralized testing, and operational flexibility, while laboratory systems remain essential for complex testing menus, high-volume processing, and situations demanding the highest possible precision [1].

Future development will likely focus on closing the performance gap between these modalities through technological innovations in biosensors, microfluidics, and artificial intelligence [17] [15]. The integration of digital health platforms with both portable and laboratory systems will enhance data accessibility and support clinical decision-making [17] [16]. Additionally, regulatory standardization will play a crucial role in ensuring consistent quality across diverse testing environments [22].

For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this evolving landscape presents both challenges and opportunities. The key to maximizing diagnostic effectiveness lies in understanding the performance characteristics, limitations, and optimal applications of both portable and laboratory instruments, then strategically deploying them within connected healthcare ecosystems that leverage the unique advantages of each approach to improve patient outcomes across diverse clinical contexts.

Deployment in Practice: Optimizing Workflows with Portable Instrumentation

The field of analytical science is undergoing a significant transformation, marked by a steady shift from centralized, fixed laboratory installations toward decentralized, on-site analysis using portable and compact instruments. This evolution is reshaping how researchers and drug development professionals approach analytical challenges across diverse environments. The traditional model of "grab and lab"—collecting samples for later analysis in a central laboratory—presents inherent limitations, including logistical complexities, potential sample degradation, and significant time delays that can impede critical decision-making processes [1] [23]. In response, technological advancements are yielding a new generation of portable analytical tools that bring the laboratory to the sample, enabling real-time analysis in field, clinical, and industrial settings.

This guide provides an objective, data-driven comparison of portable and laboratory-based analytical instruments, framed within the broader context of performance evaluation research. The core thesis explores whether modern portable devices can deliver the reliability, accuracy, and comprehensiveness required for demanding research and diagnostic applications, or if traditional lab-based systems remain the unequivocal gold standard. By examining current market trends, direct performance comparisons, and detailed experimental protocols, this article aims to equip scientists with the evidence needed to make informed tool-selection decisions based on specific application scenarios, balancing the competing priorities of convenience and analytical rigor.

Market Trends and Technological Drivers

The analytical instrument market demonstrates robust growth and innovation, with distinct trends highlighting the adoption of portable solutions. The global portable diagnostic devices market is poised to grow from USD 70.07 billion in 2024 to USD 127.79 billion by 2032, at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 7.8% [24]. This growth is largely fueled by the proliferation of point-of-care testing (POCT) and home-based testing, which demand compact, user-friendly devices [24]. Concurrently, the broader analytical instrument sector reported strong growth in Q2 2025, driven by sustained demand from the pharmaceutical, environmental, and chemical industries, with liquid chromatography (LC), gas chromatography (GC), and mass spectrometry (MS) sales contributing significantly to revenue growth [25].

A key trend cutting across various analytical techniques is miniaturization without major performance sacrifice. This is evident in the gas chromatography market, where portable and miniaturized GC systems are becoming increasingly reliable for environmental monitoring and on-site forensic investigations [26]. Similarly, the nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy market is witnessing the emergence of benchtop systems, such as Bruker's novel Fourier 80 'Multi-Talent,' which offers multinuclear capabilities (1H and 15 X-nuclei) in a permanent magnet-based benchtop format [27] [28]. A major technological driver across all platforms is the integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and machine learning. AI is enabling hyper-targeted, real-time diagnostics by analyzing complex datasets, such as patient history, physiological parameters, and environmental conditions, thereby improving the accuracy and speed of portable diagnostic platforms [24] [27].

Table 1: Analytical Instrument Market Growth Overview

| Technology Segment | Market Size (2024/2025) | Projected Market Size | CAGR | Key Growth Drivers |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Portable Diagnostic Devices | USD 70.07 billion (2024) [24] | USD 127.79 billion by 2032 [24] | 7.8% [24] | Point-of-care testing, home-based monitoring, chronic disease management [24] |

| Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy | USD 1.68 billion (2025) [27] | USD 2.73 billion by 2034 [27] | 5.54% [27] | Drug discovery, metabolomics, benchtop system adoption, materials science [27] |

| Gas Chromatography (GC) | N/A | Strong growth to 2035 [26] | N/A | Environmental monitoring, portable GC systems, food safety, pharmaceutical QA/QC [26] |

Performance Comparison: Portable vs. Laboratory Instruments

Selecting between portable and laboratory-based instruments requires a nuanced understanding of their performance characteristics. The following tables summarize the general pros and cons of each approach, followed by a comparative analysis of specific analytical techniques.

Table 2: General Pros and Cons of Portable and Laboratory Analysis

| Feature | Portable Analysis | Laboratory Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Advantage | Immediate, on-the-spot results for rapid decision-making [1] | High accuracy and precision in a controlled environment [1] |

| Throughput & Cost | Cost-effective; reduces sample transport and lab fees [1] | Higher costs due to equipment, technician expertise, and transport [1] |

| Data Comprehensiveness | May have a restricted testing range compared to lab equipment [1] | Can conduct a wider range of tests, providing more detailed analysis [1] |

| Operational Factors | Versatile for various field environments; potential for operator error [1] | Processes are standardized and staffed with trained experts [1] |

| Key Limitation | Time-consuming process involving sample transport, leading to decision-making delays [1] | May not match the ultimate precision of lab-based equipment [1] |

Chromatography and Mass Spectrometry

The performance gap between portable and lab-based systems is narrowing in separation sciences. A pioneering "lab-in-a-van" mobile LC-MS platform was deployed for on-site screening of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in environmental samples [23]. This platform, equipped with a compact capillary LC system and a single quadrupole mass spectrometer, demonstrated the ability to quantify 10 prevalent PFAS compounds in extracted soil and natural water samples with a rapid 6.5-minute runtime [23]. However, the study highlighted that sample preparation remains a major challenge in field settings, creating a need for equally compact and automated sample preparation tools to complement portable analyzers [23].

Spectroscopy

Direct performance comparisons in spectroscopy reveal context-dependent outcomes. A 2025 comparative study in Nigeria evaluated a handheld, AI-powered Near-Infrared (NIR) Spectrometer against laboratory-based High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) for detecting substandard and falsified (SF) medicines [29]. The study analyzed 246 drug samples, including analgesics, antimalarials, antibiotics, and antihypertensives.

Table 3: Performance Comparison: Handheld NIR vs. HPLC for Drug Analysis

| Parameter | Handheld NIR Spectrometer | Laboratory-based HPLC |

|---|---|---|

| Analysis Time | ~20 seconds per sample [29] | Hours to days (including transport and preparation) |

| Sample Preparation | Minimal; non-destructive [29] | Extensive; requires destruction of sample |

| Environment | Field-deployable in pharmacies and supply chains [29] | Controlled laboratory setting required |

| Overall Sensitivity | 11% (for all drug categories) [29] | Gold Standard (25% of samples failed HPLC test) [29] |

| Overall Specificity | 74% (for all drug categories) [29] | Gold Standard |

| Sensitivity (Analgesics only) | 37% [29] | Gold Standard |

| Specificity (Analgesics only) | 47% [29] | Gold Standard |

| Key Finding | The device showed low sensitivity, meaning it failed to identify many SF medicines that HPLC detected, making it risky for standalone use in regulatory settings [29]. | The study concluded that improving the sensitivity of portable devices is crucial before they can be relied upon to ensure no SF medicines reach patients [29]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To illustrate the practical implementation and validation of portable analytical methods, two key experiments from the search results are detailed below.

Protocol 1: Field-Based Screening of PFAS using Mobile LC-MS

Objective: To evaluate the performance of a mobile LC-MS platform ("lab-in-a-van") for the on-site screening and quantification of PFAS in environmental samples (soil and water) [23].

Workflow Overview:

Materials:

- Mobile Platform: "Lab-in-a-van" equipped with a compact capillary LC system coupled to a single quadrupole mass spectrometer [23].

- LC System: Compact self-contained capillary LC with full gradient capability and back pressure up to 5000 psi [23].

- Samples: Soil and natural water from potentially contaminated sites.

- Consumables: Standard LC-MS solvents, extraction cartridges for sample preparation.

Methodology:

- Deployment & Site Selection: The mobile laboratory was deployed to multiple sites of interest, covering over 3000 km and visiting 10 locations [23].

- Sample Collection: More than 200 environmental samples (soil, water) were collected on-site [23].

- Sample Preparation: Samples underwent extraction and preparation within the mobile lab. The study noted this as a key challenge, highlighting a need for more integrated, automated preparation tools [23].

- Instrumental Analysis: Prepared samples were analyzed using the portable capillary LC-MS system. The method had a 6.5-minute runtime and was calibrated to quantify 10 specific PFAS compounds [23].

- Data Analysis & Verification: Data were processed on-site. A key strategy was to identify only positive (contaminated) samples, which were then selectively shipped to a centralized commercial laboratory for confirmatory analysis, saving time and cost [23].

Protocol 2: Comparative Analysis of Drug Quality via Handheld NIR vs. HPLC

Objective: To determine the sensitivity and specificity of a handheld AI-powered NIR spectrometer in detecting substandard and falsified (SF) medicines, using HPLC as the reference standard [29].

Workflow Overview:

Materials:

- Portable Device: A patented, AI-powered handheld NIR spectrometer (750-1500 nm) with a cloud-based AI reference library [29].

- Reference Method: High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC).

- Samples: 246 drug samples purchased from randomly selected pharmacies across Nigeria. The samples included four categories: analgesics, antibiotics, antihypertensives, and antimalarials [29].

- NIR Reference Library: The device's company sourced authentic branded drug samples to build and update the spectral reference library prior to the study [29].

Methodology:

- Blinded Sample Acquisition: Enumerators acted as mystery shoppers to purchase a predefined list of 20 branded drugs from randomly selected pharmacies in both urban and rural areas [29].

- Field Testing with NIR: All purchased samples were tested on-site with the handheld NIR spectrometer. The process took approximately 20 seconds per sample. The device compared the spectral signature and intensity of the sample against the reference library, returning a "match" or "non-match" result [29].

- Laboratory Confirmation with HPLC: A representative sub-sample of 246 products was transported to a central laboratory (Hydrochrom Analytical Services Limited, Lagos) for quantitative compositional analysis using HPLC, which served as the gold standard [29].

- Data Analysis: The results from the NIR device were compared against the HPLC results. Sensitivity (ability to correctly identify SF medicines) and specificity (ability to correctly identify non-SF medicines) of the NIR device were calculated for all medicines and for specific drug categories [29].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The experiments cited rely on a range of essential reagents and materials to function. The following table details key items and their functions in portable and laboratory analyses.

Table 4: Key Research Reagents and Materials

| Item | Function in Analysis | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Authentic Drug Standards | Provide reference spectral signatures for comparison; essential for calibrating portable spectrometers and HPLC methods [29]. | Detection of substandard and falsified medicines [29]. |

| LC-MS Grade Solvents | Act as the mobile phase in chromatography; high purity is critical for preventing background noise and instrument damage [23]. | Mobile LC-MS analysis of PFAS [23]. |

| Solid-Phase Extraction (SPE) Cartridges | Isolate, pre-concentrate, and clean up target analytes from complex sample matrices like soil or water before instrumental analysis [23]. | Sample preparation for environmental analysis [23]. |

| Dilute NaCl Eluent | Serves as the mobile phase (eluent) in Ion Chromatography (IC); a low-hazard chemical suitable for portable systems [23]. | Portable IC analysis of nutrients (nitrite, nitrate) in water [23]. |

| Post-column Reagents | React with separated analytes post-column to form a detectable product; used in portable IC for ammonium detection [23]. | Simultaneous determination of ammonium, nitrite, and nitrate [23]. |

| Standard 5 mm NMR Tubes | Hold samples for analysis in NMR spectrometers; standardization ensures compatibility and reproducibility [28]. | Benchtop FT-NMR analysis (e.g., Bruker Fourier 80) [28]. |

The evidence demonstrates that the choice between portable and laboratory-based instruments is not a matter of simple superiority but of strategic alignment with the research or diagnostic scenario. Portable analyzers are unequivocally superior in scenarios demanding immediate results, operational cost-efficiency, and analysis in remote or logistically challenging environments. Their value is proven in rapid screening, on-site triage, and guiding time-sensitive decisions. However, their limitations in sensitivity, specificity, and analytical comprehensiveness must be acknowledged, as seen in the NIR drug study where low sensitivity posed a significant risk [29].

Conversely, laboratory-based systems remain the indispensable choice for applications requiring the highest possible accuracy, precision, and comprehensive data. They are critical for definitive confirmation testing, method development, and analyzing highly complex samples where trace-level detection is paramount.

Therefore, the optimal strategy is often a hybrid one. As demonstrated by the mobile PFAS screening lab, portable devices can be used for rapid, high-throughput on-site screening, while positive or non-conforming samples are sent to a central lab for definitive, gold-standard analysis [23]. This approach maximizes efficiency, minimizes costs, and ensures that the strengths of both paradigms are leveraged effectively. For researchers and drug development professionals, the key is to clearly define the analytical problem—considering required speed, accuracy, and operational context—before matching the appropriate tool to the need.

The paradigm of chemical and biological analysis is undergoing a fundamental shift, moving from centralized laboratories to the point of need. Portable mass spectrometers, DNA sequencers, and analytical instruments are redefining operational workflows across pharmaceuticals, environmental science, and clinical diagnostics. These devices combine miniaturized instrumentation, rugged engineering, and integrated data pipelines to deliver laboratory-grade capabilities in field and point-of-care settings [30]. This transition is driven by technological convergence in sensor miniaturization, ion optics optimization, and embedded data analytics, enabling levels of sensitivity and selectivity previously restricted to centralized labs [30].

This guide provides a performance comparison framework for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals evaluating portable against traditional laboratory instruments. The content is structured within a broader thesis on performance comparison, presenting objective experimental data, detailed methodologies, and standardized validation protocols to inform procurement and operational decisions. As the market for these tools grows—with the portable analytical instruments market valued at $7.6 billion in 2025 and the portable gene sequencer market projected to reach $8.59 billion by 2031—understanding their capabilities and limitations becomes essential for leveraging their full potential in research and development [31] [32].

Performance Comparison: Portable vs. Laboratory Instruments

Selecting the appropriate analytical tool requires balancing performance specifications with operational constraints. The following comparison tables summarize key metrics across instrument categories, providing a baseline for objective evaluation.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Portable and Laboratory Mass Spectrometers

| Performance Metric | Portable Mass Spectrometers | Laboratory Benchtop Systems |

|---|---|---|

| Mass Resolution | Moderate (Varies by technology: Ion Trap, Quadrupole) [30] | High to Very High (e.g., Orbitrap, Magnetic Sector) [30] |

| Analysis Time | Seconds to minutes for on-site analysis [30] | Minutes to hours, including sample transport [30] |

| Typical Sensitivity | Parts-per-billion (ppb) to parts-per-trillion (ppt) for targeted compounds [30] | Parts-per-trillion (ppt) and below [33] |

| Sample Throughput | Lower; optimized for rapid, individual samples [30] | High; automated for batch processing [34] |

| Environmental Ruggedness | Designed for field use (variable temp, humidity, shock) [35] | Requires controlled laboratory conditions [34] |

| Data Complexity | Curated, actionable results; onboard data analysis [30] | Raw, complex data requiring expert interpretation [33] |

| Upfront Cost (USD) | Lower initial investment [32] | High (>$500,000 for high-end systems) [34] |

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Portable and Laboratory DNA Sequencers

| Performance Metric | Portable Sequencers (e.g., Nanopore) | Laboratory NGS Systems |

|---|---|---|

| Read Length | Long reads (up to millions of bases) [36] | Short to long reads (technology-dependent) [31] |

| Sequencing Speed | Real-time data streaming; minutes to hours [36] | Batch processing; requires run completion (hours to days) [31] |

| Accuracy | Moderate (~90-97%); improving with chemistry/software [36] | Very High (>99.9%) [31] |

| Throughput per Run | Lower (e.g., 10-50 Gb for Flongle/GridION) [31] | Very High (hundreds of Gb to Tb) [31] |

| Primary Application | Rapid diagnostics, field surveillance, targeted sequencing [36] | Whole-genome sequencing, large-scale genomic studies [31] |

| Workflow Dependency | Relies on host computer for basecalling, introducing security considerations [37] | Self-contained instrument with integrated computing [37] |

Table 3: Performance Comparison of Portable and Laboratory Gas Analyzers

| Performance Metric | Portable Gas Analyzers | Laboratory Gas Chromatographs |

|---|---|---|

| Measurement Range | Targeted gases (e.g., O2, CO2, CH4, VOCs) [38] | Comprehensive separation of complex mixtures [38] |

| Accuracy/Precision | High for specific sensors (e.g., ±2% for ABB analyzers) [38] | Very High, with certified standard methods [38] |

| Analysis Time | Real-time/continuous monitoring [38] | Minutes to hours per sample [38] |

| Multi-analyte Capability | Limited to configured sensors; FTIR analyzers offer broader detection [38] | Virtually unlimited with method development [38] |

| Key Strengths | Immediate hazard identification, leak detection, personal exposure monitoring [38] | Definitive identification and quantification for regulatory compliance [38] |

Key Insights from Comparative Data

- Operational Agility vs. Ultimate Performance: Portable instruments trade peak performance for operational agility. They provide decision-quality data at the point of need, eliminating delays from sample transport and central lab queuing [30]. This is crucial for time-sensitive applications like infectious disease outbreak response, where portable nanopore sequencers delivered results in less than 24 hours during the Ebola epidemic [37].

- Contextual Data Complexity: Laboratory systems generate vast, complex datasets requiring expert bioinformaticians or chemists. Portable devices increasingly embed onboard chemometric models and adaptive acquisition routines to provide simplified, actionable outputs directly to field operators [30].

- Total Cost of Ownership: While portable instruments have lower acquisition costs, researchers must consider consumables, calibration, and maintenance. Laboratory systems involve significant capital expenditure but offer lower per-sample costs for high-volume applications [32].

Experimental Protocols for Validation Studies

Validating portable instrument performance against laboratory standards requires rigorous, methodical protocols. The following sections detail experimental methodologies cited in industry reports and research.

Protocol for Mass Spectrometer Field Validation

Objective: To validate the analytical performance of a portable mass spectrometer against a laboratory-grade LC-MS/MS system for detecting pharmaceutical contaminants in water samples [30].

Materials and Reagents:

- Portable Mass Spectrometer (e.g., equipped with an Ion Trap or Quadrupole analyzer)

- Laboratory LC-MS/MS System (e.g., Triple Quadrupole system)

- Standard Reference Materials: Certified analyte standards (e.g., carbamazepine, diclofenac)

- Sample Preparation Kit: Including solid-phase extraction (SPE) cartridges, solvents, and filtration units

- Internal Standards: Isotopically labeled versions of target analytes

Methodology:

- Sample Collection and Preparation: Collect 1-liter water samples from various sources (river, effluent). Split each sample: one portion is prepared for portable MS analysis using a simplified dilution and internal standard addition, while the other undergoes full SPE concentration for LC-MS/MS.

- Instrument Calibration: Calibrate both instruments using a series of standard solutions (e.g., 0.1, 1, 10, 100 µg/L). The portable MS uses a direct infusion method, while the LC-MS/MS uses a chromatographic method.

- Analysis: Analyze all samples in triplicate on both instruments. For the portable MS, perform direct analysis with a minimal cleanup step. For LC-MS/MS, execute the full chromatographic separation.

- Data Comparison: Compare the quantitative results (concentration detected) for each analyte across the two platforms. Key validation parameters include:

- Limit of Detection (LOD) and Quantification (LOQ)

- Linear Dynamic Range

- Accuracy (expressed as % recovery of known spikes)

- Precision (Relative Standard Deviation of replicate measurements)

Protocol for Portable Sequencer Accuracy Assessment

Objective: To determine the consensus accuracy and variant-calling performance of a portable sequencer relative to an Illumina system for a bacterial genome [36].

Materials and Reagents:

- Portable Sequencer (e.g., Oxford Nanopore MinION)

- Next-Generation Sequencer (e.g., Illumina MiSeq)

- Genomic DNA Sample: From a well-characterized bacterial strain (e.g., E. coli K-12)

- Library Preparation Kits: Specific to each sequencing platform (e.g., Ligation Sequencing Kit for Nanopore)

- Computing Hardware: Host computer with dedicated GPU for real-time basecalling

Methodology:

- Library Preparation: Prepare sequencing libraries from the same DNA extraction aliquot using the manufacturer's protocols for both the portable and Illumina platforms.

- Sequencing Runs: Sequence the library on both instruments. For the portable device, perform basecalling in real-time and also collect raw signals for subsequent basecalling using different algorithms.

- Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Portable Data: Assemble the long reads into a consensus genome using a tool like Flye. Polish the assembly using Medaka.

- Illumina Data: Map the short reads to the reference genome using BWA-MEM to generate a high-confidence consensus.

- Variant Calling: Identify single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and insertions/deletions (indels) in both assemblies using the Illumina-based consensus as a benchmark.

- Performance Metrics:

- Consensus Accuracy: Calculate the identity percentage of the portable sequencer's assembly when aligned to the reference genome.

- Variant Calling Concordance: Determine the sensitivity (true positive rate) and precision of variant calls from the portable data compared to the Illumina variant set.

Cross-Platform Validation for Gas Analyzers

Objective: To compare the measurement accuracy of a portable FTIR gas analyzer against a laboratory-based Gas Chromatograph-Mass Spectrometer (GC-MS) for identifying volatile organic compounds (VOCs) in air samples [38].

Materials and Reagents:

- Portable FTIR Gas Analyzer (e.g., Gasmet series)

- Laboratory GC-MS System

- Calibration Gas Standards: Certified mixtures of target VOCs (e.g., benzene, toluene, xylene) in nitrogen

- Tedlar Bags or Sorbent Tubes: For air sample collection and storage

Methodology:

- Field Sampling: Collect air samples at a monitoring site using Tedlar bags. Simultaneously, analyze the ambient air directly on-site with the portable FTIR analyzer, recording the concentration readings.

- Laboratory Analysis: Transport the collected bag samples to the laboratory and analyze them using the standard GC-MS method for VOCs.

- Controlled Chamber Test: In a laboratory chamber, generate known concentrations of VOC mixtures. Measure these concentrations simultaneously with the portable FTIR analyzer and by collecting samples for GC-MS analysis.

- Data Validation: Perform linear regression analysis to correlate the concentration values obtained from the portable analyzer with those from the GC-MS for each target compound. Report the coefficient of determination (R²) and the measurement uncertainty for the portable device.

Workflow Visualization

Understanding the operational and data flow of portable instruments is key to integrating them into existing research pipelines. The following diagrams illustrate core workflows.

Portable DNA Sequencer Operational and Data Flow

Diagram 1: Portable DNA Sequencer simplified workflow, highlighting the host machine as a potential vulnerability surface for data security [37].

Portable Mass Spectrometer Analysis Workflow

Diagram 2: Portable Mass Spectrometer analysis workflow, showcasing the streamlined path from sample to result with minimal preparation [30].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Successful deployment of portable analytical tools relies on a suite of supporting reagents and materials. The following table details key components for building a robust field-ready analytical capability.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Portable Instrumentation

| Item Name | Function & Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Certified Standard Reference Materials | Calibration and quantitative accuracy verification for mass spectrometers and gas analyzers [38]. | Traceability to national standards (e.g., NIST) is critical for regulatory compliance. |

| Solid-Phase Extraction (SPE) Cartridges | Rapid sample clean-up and pre-concentration of analytes from complex matrices like water or soil extracts for MS analysis [30]. | Select sorbent chemistry (e.g., C18, HLB) based on target analyte properties. |

| Library Preparation Kits (Sequencing) | Fragment DNA/RNA and attach adapters/ligands required for sequencing on portable platforms (e.g., Nanopore ligation kits) [36]. | Kits are often platform-specific. Throughput and input DNA requirements vary. |

| Flow Cells (Sequencing) | Disposable cartridges containing the sensors for detecting DNA/RNA strands in nanopore sequencers [36]. | A key consumable; shelf-life and storage conditions are important for optimal performance. |

| Calibration Gas Mixtures | Provide known concentrations of target gases to calibrate portable gas analyzers ensuring measurement accuracy [38]. | Stability of mixtures, especially for reactive gases, and compatibility with analyzer technology. |

| Isotopically Labeled Internal Standards | Added to samples for MS analysis to correct for matrix effects and losses during sample preparation, improving quantification [30]. | Ideally, the standard is a chemically identical version of the analyte with different mass. |

| DNA/RNA Preservation Buffers | Stabilize genetic material in field-collected samples to prevent degradation before sequencing [36]. | Essential for maintaining sample integrity during transport from remote locations. |

The systematic comparison of portable mass spectrometers, sequencers, and analyzers demonstrates their transformative role in modern scientific research. While traditional laboratory instruments remain the gold standard for ultimate sensitivity and throughput, portable alternatives provide unparalleled speed, flexibility, and operational agility for a wide range of field and point-of-care applications [35] [31] [38].

The future trajectory of these technologies is clear: continued miniaturization without performance compromise, deeper integration of AI and machine learning for automated data analysis and predictive diagnostics, and the development of more robust and secure systems [34] [30] [39]. The emergence of security concerns, particularly for portable sequencers that rely on external host computers, underscores the need for a zero-trust security approach throughout the analytical workflow [37].

For researchers and drug development professionals, the decision to adopt portable instrumentation must be guided by a clear understanding of application-specific requirements. When the experimental question values speed, location-specific data, and operational flexibility over the absolute highest data precision, portable tools represent a powerful and increasingly capable new generation in the scientific toolkit.

The modern laboratory is undergoing a radical transformation, shifting from isolated, manual operations to connected, intelligent ecosystems. This evolution is primarily driven by the convergence of three powerful technologies: the Internet of Things (IoT), Artificial Intelligence (AI), and Cloud Connectivity. This integration is blurring the traditional lines between portable and laboratory-based instruments, creating a new class of smart analytical tools that offer unprecedented levels of efficiency, data richness, and operational flexibility.

The debate between portable and lab-based analysis is evolving beyond simple comparisons of accuracy versus convenience. While traditional lab analysis provides highly accurate results in a controlled environment, it often involves longer turnaround times and higher costs due to equipment use, technician expertise, and sample transport [1]. Conversely, portable analysis enables on-the-spot decision-making and reduces logistical challenges, particularly in remote areas, though it may sometimes sacrifice the precision of lab-based equipment [1]. The integration of IoT, AI, and cloud technologies is not rendering this debate obsolete but is instead creating a synergistic environment where both modalities can be leveraged for their unique strengths within a unified data framework. This guide objectively compares the performance of these integrated systems, providing researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with the experimental data needed to inform their technology adoption strategies.

Technological Foundations: IoT, AI, and Cloud Connectivity

The Internet of Things (IoT) in the Laboratory

The Internet of Things refers to the network of physical objects—"things"—embedded with sensors, software, and other technologies to connect and exchange data with other devices and systems over the internet [40]. In laboratory environments, IoT manifests as smart, connected devices that continuously collect and transmit operational and experimental data. The number of connected IoT devices is projected to grow 14% in 2025 alone, reaching 21.1 billion globally, a testament to its rapid adoption across sectors including life sciences [41].

Key IoT connectivity technologies relevant to laboratories include:

- Wi-Fi IoT: Comprising 32% of all IoT connections, Wi-Fi remains the largest technology for IoT connectivity, with rising adoption of low-power Wi-Fi for IoT devices utilizing Wi-Fi 6 features [41].

- Bluetooth IoT: Accounting for 24% of connected IoT devices worldwide, Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE) leads battery-powered IoT connectivity [41].

- Cellular IoT (2G, 3G, 4G, 5G): Making up 22% of global IoT connections, cellular IoT is experiencing growth driven by technology shifts including 5G becoming the standard for high-reliability, low-latency use cases [41].

Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning