Precision vs Reproducibility in Analytical Methods: A Guide for Robust Scientific Research

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive guide to understanding and applying the critical concepts of precision and reproducibility in analytical method validation.

Precision vs Reproducibility in Analytical Methods: A Guide for Robust Scientific Research

Abstract

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive guide to understanding and applying the critical concepts of precision and reproducibility in analytical method validation. It explores the foundational definitions, practical methodologies, and regulatory frameworks, before addressing common troubleshooting scenarios and the formal process of method validation and transfer. By clarifying the distinct roles of repeatability, intermediate precision, and reproducibility, the content aims to equip professionals with the knowledge to enhance data reliability, ensure regulatory compliance, and address the pervasive challenge of irreproducibility in scientific research.

Precision and Reproducibility Defined: Laying the Groundwork for Reliable Data

In the fields of analytical chemistry, pharmaceutical development, and clinical laboratory science, precision is a fundamental parameter of data quality, formally defined as the "closeness of agreement between independent test or measurement results obtained under specified conditions" [1]. This concept is distinct from accuracy, which denotes closeness to a true value; precision relates specifically to the dispersion of repeated measurements [1]. Understanding and quantifying precision is essential for researchers and scientists who must ensure the reliability of their analytical methods, particularly in regulated environments like drug development where method validation is mandatory [2].

The "specified conditions" under which measurements are obtained critically determine the type of precision being evaluated, leading to three primary classifications: repeatability, intermediate precision, and reproducibility [1]. These categories represent a hierarchy of variability, with repeatability showing the smallest dispersion under identical conditions and reproducibility exhibiting the largest across different laboratories [3] [1]. This guide systematically compares these precision types through their experimental protocols, quantitative performance data, and practical applications in analytical science.

Hierarchical Levels of Precision

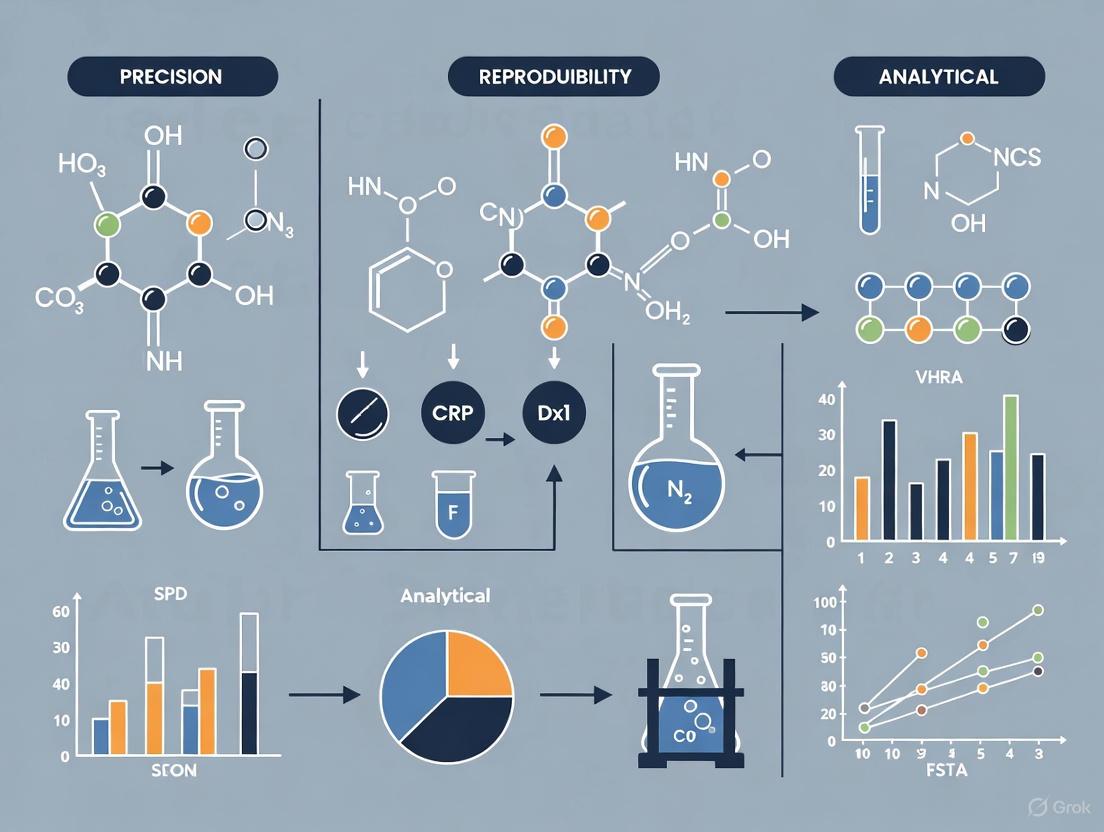

Precision is not a single characteristic but a hierarchy that encompasses different levels of variability depending on changing conditions. The diagram below illustrates this relationship, showing how variability increases from repeatability to reproducibility.

Repeatability

Repeatability represents the highest level of precision, measuring variability under identical conditions where the same procedure, operators, equipment, and location are used over a short time period [3] [1]. Also known as intra-assay precision, it demonstrates the best-case scenario for method consistency, typically yielding the smallest standard deviation or relative standard deviation (RSD) among precision measures [2] [3].

Intermediate Precision

Intermediate precision measures consistency within a single laboratory under varying internal conditions that may change over longer timeframes (days or months), including different analysts, instruments, reagent batches, or columns [4] [2] [3]. This parameter assesses how well a method withstands normal operational variations expected in day-to-day laboratory practice [4]. The term "ruggedness" was previously used but has been largely superseded by intermediate precision in current guidelines [2].

Reproducibility

Reproducibility represents the broadest measure, evaluating precision between different laboratories in collaborative studies [4] [2] [3]. Also called "between-lab reproducibility," it assesses method transferability and global application suitability [4] [3]. Reproducibility yields the largest variability measure due to incorporating the most diverse factors, including different locations, equipment, calibrants, and environmental conditions [1].

Quantitative Comparison of Precision Types

The table below summarizes key characteristics and typical experimental outcomes for the three precision categories, illustrating how variability increases as conditions become less controlled.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Precision Types in Analytical Method Validation

| Feature | Repeatability | Intermediate Precision | Reproducibility |

|---|---|---|---|

| Testing Environment | Same lab, short period | Same lab, extended period | Different laboratories |

| Key Variables | None (identical conditions) | Analyst, day, instrument, reagents, columns | Lab location, equipment, analysts, environmental conditions |

| Experimental Design | Minimum 9 determinations over 3 concentration levels; or 6 at 100% [2] | Different analysts prepare/analyze replicates using different systems over multiple days [2] | Collaborative studies between multiple laboratories using identical methods [4] [2] |

| Statistical Reporting | % RSD [2] | % RSD, statistical comparison of means (e.g., Student's t-test) [2] | Standard deviation, % RSD, confidence interval [2] |

| Typical Variability | Lowest | Moderate | Highest |

| Primary Application | Establish optimal performance under controlled conditions | Verify robustness for routine laboratory use | Demonstrate method transferability and global applicability |

Experimental Protocols for Precision Assessment

Standardized Experimental Workflow

The following diagram outlines a generalized experimental workflow for precision studies, with specific variations for each precision type detailed in subsequent sections.

Protocol for Repeatability Determination

- Sample Preparation: Prepare a minimum of nine determinations covering the specified range of the procedure (three concentration levels, three repetitions each) or a minimum of six determinations at 100% of the test concentration [2].

- Analysis Conditions: All measurements must be performed by the same analyst using the same instrument, reagents, and equipment within a short time frame (typically one day or one analytical run) [3] [1].

- Statistical Analysis: Calculate the standard deviation and relative standard deviation (% RSD) of the measurements. The % RSD represents the primary metric for repeatability [2].

Protocol for Intermediate Precision

- Experimental Design: Implement a structured design that systematically varies key factors including different analysts, instruments, and days [2]. The study should extend over a period of at least several months to incorporate normal laboratory variations [3].

- Sample Analysis: Two or more analysts independently prepare and analyze replicate sample preparations using different HPLC systems or instruments where applicable [2]. Each analyst should prepare their own standards and solutions.

- Statistical Evaluation: Calculate % RSD for the combined data. Compare mean values between analysts using statistical tests (e.g., Student's t-test) to determine if significant differences exist [2].

Protocol for Reproducibility

- Collaborative Study: Organize an inter-laboratory study involving multiple laboratories (typically at least three to five) following the same standardized analytical method [4] [2].

- Standardized Materials: Distribute identical test samples and reference standards to all participating laboratories to minimize material-based variability.

- Data Analysis: Collect results from all participants and calculate the overall standard deviation, % RSD, and confidence intervals. The between-laboratory variance represents reproducibility [2].

Research Reagent Solutions for Precision Studies

Table 2: Essential Materials and Reagents for Precision Experiments

| Item | Function in Precision Studies | Considerations for Precision |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Standards | Provide known concentration for accuracy assessment and calibration | High purity and well-characterized identity essential; certified reference materials preferred [2] |

| Chromatographic Columns | Separation component in HPLC/UPLC methods | Different batches/lots tested in intermediate precision; specific type may be specified in method [4] [2] |

| Reagents & Solvents | Mobile phase preparation, sample extraction | Different batches/lots tested in intermediate precision; grade and supplier should be specified [2] [3] |

| QC Materials | Monitor system performance and stability | Should mimic patient samples; used in precision and accuracy monitoring [5] [1] |

| Calibrators | Establish relationship between instrument response and analyte concentration | Different sets used by different analysts in intermediate precision studies [2] [3] |

Impact of Precision on Data Interpretation and Clinical Decision-Making

Understanding precision hierarchy has practical implications for interpreting laboratory data and making clinical or regulatory decisions. As variability increases from repeatability to reproducibility, so does the uncertainty associated with individual measurements [1]. This progression directly impacts how researchers establish acceptance criteria and how clinicians interpret serial measurements from patients.

Under repeatability conditions, bias (if present) is most evident as imprecision is minimized. In contrast, under reproducibility conditions, bias behaves more like a random variable and contributes significantly to the observed variation [1]. This explains why reproducibility standard deviation is always larger than intermediate precision, which in turn exceeds repeatability standard deviation. For researchers developing analytical methods, this hierarchy underscores the importance of validating methods under conditions mirroring their ultimate application environment—single laboratory use requires intermediate precision assessment, while methods intended for multiple sites necessitate reproducibility studies [4] [2].

In clinical applications, biological variation inherent to human metabolism often exceeds analytical variation, particularly with modern precise methods [1]. However, understanding analytical precision remains essential for distinguishing true biological changes from measurement noise, especially when monitoring disease progression or treatment response through serial measurements. Proper evaluation of both biological and analytical variation components is fundamental to personalized laboratory medicine [1].

In the realm of analytical chemistry and pharmaceutical quality control, the validation of a method is critical to ensure the generation of reliable, consistent, and accurate data [4]. Precision, defined as the "closeness of agreement between replicate measurements on the same or similar objects," is a cornerstone of this validation [6]. However, precision is not a single, monolithic concept; it is evaluated at three distinct levels—repeatability, intermediate precision, and reproducibility—each accounting for different sources of variability [3] [2]. This guide deconstructs these levels, providing a structured comparison and detailed experimental methodologies to empower researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals in assessing analytical method performance.

#

| Precision Level | Testing Environment | Key Variables Assessed | Typical Expression of Results | Primary Goal |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Repeatability [3] | Same lab, short period [3] | Same procedure, operators, system, and conditions [3] | Standard deviation (SD), % Relative Standard Deviation (%RSD) [2] | Measure the smallest possible variation under optimal conditions [3] |

| Intermediate Precision [4] | Same lab, extended period (e.g., months) [3] | Different analysts, instruments, days, reagent/column batches [3] [4] | Standard deviation (SD), %RSD, statistical comparison of means (e.g., Student's t-test) [2] | Assess method stability under typical day-to-day lab variations [4] |

| Reproducibility [4] | Different laboratories [3] [4] | Different locations, equipment, and analysts [4] [6] | Standard deviation (SD), %RSD, confidence interval [2] | Demonstrate method transferability and global robustness [4] |

#

Experimental Protocol for Repeatability

- Objective: To determine the ability of a method to generate consistent results over a short time interval under identical conditions (intra-assay precision) [2].

- Sample Preparation: A homogeneous sample is prepared at the target concentration (100%) or at a minimum of three concentration levels covering the specified range of the procedure [2].

- Analysis: Under repeatability conditions, a minimum of six determinations at 100% concentration, or a minimum of nine determinations across three concentration levels (three replicates each), are performed [2]. All analyses must be conducted by the same analyst, using the same instrument, same reagents, and under the same operating conditions over a short period, typically one day or one sequence [3].

- Data Analysis: The standard deviation (SD) and relative standard deviation (%RSD) of the results are calculated. Repeatability is expected to show the smallest possible variation [3] [2].

Experimental Protocol for Intermediate Precision

- Objective: To evaluate the within-laboratory variation due to random events that occur during routine operation, such as different days, different analysts, or different equipment [2].

- Experimental Design: A designed experiment is used so that the effects of individual variables can be monitored [2]. A common approach involves two analysts independently preparing and analyzing replicate sample preparations.

- Analysis: Each analyst uses their own standards and solutions, and may use a different HPLC system or instrument for the analysis. These experiments are conducted over an extended period, such as several weeks or months [3] [2].

- Data Analysis: The SD and %RSD for the entire dataset are calculated to express intermediate precision. Furthermore, the percent difference in the mean values between the two analysts' results is calculated and can be subjected to statistical testing (e.g., a Student's t-test) to determine if there is a significant difference between the means obtained by different analysts [2].

Experimental Protocol for Reproducibility

- Objective: To assess the precision between measurement results obtained in different laboratories, often as part of collaborative inter-laboratory studies [3] [4].

- Experimental Design: Multiple laboratories (often two or more) are provided with the same analytical method and the same homogeneous test samples [2].

- Analysis: Each laboratory prepares its own standards and solutions and uses its own equipment and analysts to perform the analysis according to the written procedure. The laboratories involved are typically different from those involved in the intermediate precision studies [2].

- Data Analysis: The SD, %RSD, and confidence intervals for the results from all laboratories are calculated. The percent difference in the mean values between the laboratories is also reported and must be within pre-defined specifications [2].

#

#

When conducting experiments to validate precision, attention to reagents and consumables is paramount. Inconsistencies in these materials can introduce unintended variability and compromise results [7].

| Item Category | Specific Example | Critical Function | Considerations for Precision |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chromatographic Reagents | HPLC-grade solvents & columns | Create the separation medium for analysis | Use the same brand and grade; monitor column performance over time [3] [2]. |

| Reference Standards | Drug substance certified reference material (CRM) | Serves as the benchmark for accuracy and calibration | Source from certified suppliers; document purity and lot number [2]. |

| Sample Preparation Consumables | Low-retention pipette tips | Ensure accurate and precise liquid handling | Use the same type of tips to minimize volume variation; avoid mixing lots mid-study [7]. |

| Mobile Phase Additives | High-purity buffers (e.g., phosphate, formate) | Modify the mobile phase to achieve desired separation | Prepare consistently (e.g., pH, molarity); verify pH before use [7]. |

| Quality Control Materials | In-house quality control (QC) sample | Monitors system performance and data reliability | Use a homogeneous, stable sample representative of the analyte [2]. |

Reproducibility is a critical benchmark in analytical science, confirming that a method can produce consistent results when the same protocol is tested across different laboratories, by different analysts, using different equipment [8] [9]. This article compares reproducibility with the related concept of precision and provides a detailed guide for designing and executing a multi-laboratory study to assess it.

Precision vs. Reproducibility: A Foundational Comparison

In analytical chemistry and laboratory medicine, precision and reproducibility are distinct but related performance characteristics. Precision, often quantified as repeatability, refers to the closeness of agreement between independent test results obtained under the same conditions—same laboratory, same analyst, same instrument, and a short interval of time [8] [9]. In contrast, reproducibility is assessed under changed conditions, specifically across different laboratories [8].

The following table summarizes the key differences:

| Feature | Precision (Repeatability) | Reproducibility |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Closeness of agreement between independent results under the same conditions [9]. | Closeness of agreement between results from different laboratories using the same method [8]. |

| Testing Conditions | Same lab, same analyst, same instrument, short time frame. | Different labs, different analysts, different instruments [8]. |

| Primary Goal | Measure the random error or "noise" of a method within one lab. | Confirm the method's robustness and transferability between labs. |

| Quantified by | Standard Deviation or % Coefficient of Variation (%CV). | Inter-laboratory Standard Deviation or %CV. |

This relationship is part of a broader framework for understanding different types of reproducibility, as outlined in statistical literature. One model classifies reproducibility into five types (A-E), where reproducibility across different labs is classified as Type D [8]:

Reproducibility Type D: Experimental conclusions are reproducible if new data from a new study carried out by a different team of scientists in a different laboratory, using the same method of experiment design and analysis, lead to the same conclusion [8].

Reproducibility Type D Workflow

Designing a Reproducibility Study: Core Experimental Protocol

A well-designed comparison of methods experiment is the standard approach for assessing reproducibility and estimating systematic error [5]. The following workflow outlines the key stages of this experiment.

Reproducibility Study Workflow

Phase 1: Planning and Design

- Define Goals and Acceptance Criteria: Before beginning, establish numerical goals for acceptable performance (e.g., maximum allowable bias). This ensures objective conclusions [10]. The goals should be based on the intended use of the method and clinically relevant decision points [5].

- Select Participating Laboratories: A minimum of 40 different patient specimens is recommended, carefully selected to cover the entire working range of the method and represent the expected spectrum of sample matrices [5].

- Select and Prepare Patient Specimens: Specimens should be stable and analyzed by the test and comparative methods within a short time frame (e.g., two hours) to prevent degradation from causing observed differences [5]. The experiment should be conducted over a minimum of 5 days to account for day-to-day variability [5].

Phase 2: Sample Analysis

- Analysis in Multiple Labs: Each participating laboratory analyzes the same set of patient specimens using the standardized method protocol.

- Replicate Measurements: While each specimen is often analyzed singly by the test and comparative methods, there are advantages to making duplicate measurements. Duplicates provide a check on the validity of individual measurements and help identify sample mix-ups or transposition errors [5]. If using replicates, calculations can be based on the average of the replicate results to reduce error in bias estimation [10].

Phase 3: Data Analysis and Statistical Evaluation

The collected data is analyzed to estimate systematic error and quantify reproducibility.

- Graphical Analysis: The first step is to graph the data. A difference plot (Bland-Altman plot) is a fundamental tool, displaying the difference between the test and reference results (y-axis) versus the reference result (x-axis) [5]. This visual inspection helps identify patterns, potential outliers, and the nature of systematic errors.

- Statistical Calculations: For data covering a wide analytical range, linear regression analysis is used to model the relationship between the test and reference methods. This provides the regression line's slope (indicating proportional error) and y-intercept (indicating constant error) [5]. The systematic error at a critical medical decision concentration (Xc) can then be calculated as SE = (a + b*Xc) - Xc, where 'a' is the intercept and 'b' is the slope [5].

- Quantifying Reproducibility: The intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC) is a key statistic for assessing reproducibility between raters or laboratories. In one study of a physical measurement technique, ICC values for inter-rater reproducibility ranged from 0.67 to 0.79, which were considered "good or moderate" [11].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

A successful reproducibility study requires carefully selected materials and reagents to ensure consistency and validity.

| Item Category | Specific Examples | Critical Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Standards | USP/EP Reference Standards; Certified Pure Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API) [9] | Provides an unbiased benchmark with known properties to calibrate instruments and validate the accuracy of the method. |

| Patient Specimens | Human serum/plasma; Tissue homogenates; 40+ unique samples covering the analytical range [5] | Serves as the real-world test matrix for comparing method performance across laboratories. |

| Analytical Instruments | HPLC Systems; Mass Spectrometers; Clinical Chemistry Analyzers [9] | The platform on which the analytical method is performed; must be properly calibrated and maintained. |

| Validated Reagents | Specific Antibodies (for ELISA); HPLC-grade Solvents; New Reagent Lots [10] [12] | Key components that drive the analytical reaction; their quality and consistency are paramount to reproducible results. |

| Data Analysis Software | Statistical packages (R, Python); Validation Manager Software [13] [10] | Enables consistent statistical analysis, graphing (e.g., difference plots), and calculation of parameters like bias and ICC. |

Interpreting Results and Establishing Method Robustness

Interpreting the data from a reproducibility study requires evaluating both statistical and clinical significance. A observed bias might be statistically significant but must also be assessed for its impact on medical or scientific decision-making [12]. Would the difference between two results lead to a different action, or is the outcome the same from a clinical perspective?

Establishing that a method is reproducible provides a foundation for scalable manufacturing and global market access in the pharmaceutical industry. A reproducible formulation and analytical method can be confidently transferred from a research and development lab to a large-scale commercial manufacturing facility in a different location, ensuring product consistency for patients [9].

| Feature | Precision | Reproducibility |

|---|---|---|

| Core Definition | Closeness of agreement between multiple test results obtained under specified conditions [14] [15]. | Degree of agreement between measurements of the same quantity made by different people, in different laboratories, or with different experimental setups [14] [3] [16]. |

| Scope of Variability | Measures random error and scatter under varying conditions within a single laboratory [14]. | Measures the influence of systematic differences between laboratories, operators, and equipment [14]. |

| Experimental Conditions | Assessed under a range of conditions, from identical (repeatability) to within-lab variations (intermediate precision) [14] [15]. | Assessed under distinctly different conditions, typically involving different laboratories [14] [3]. |

| Primary Context | Within-laboratory consistency [3]. | Between-laboratory consistency, often assessed during method transfer or standardization [14] [15] [3]. |

| Key Question | "How close are our results to each other under various conditions in our lab?" | "Can another lab, using our method, obtain the same results we do?" [14] |

| Typical Statistical Measure | Standard Deviation (SD) and Relative Standard Deviation (RSD) [14] [15]. | Standard Deviation calculated from results across multiple laboratories [14]. |

| Hierarchy / Relationship | An overarching term that includes repeatability (minimal variability) and intermediate precision (more variability) [14] [15]. | Considered the highest level of precision, representing the broadest set of influencing factors [14] [3]. |

Experimental Protocols for Assessment

The following standardized methodologies are used to quantify precision and reproducibility, as outlined in guidelines such as ICH Q2(R1) [14] [15].

Protocol for Precision (Repeatability and Intermediate Precision)

- Objective: To determine the random error of the analytical method under within-laboratory conditions.

- Sample Preparation: Analyze a minimum of 6 determinations at 100% of the test concentration. Alternatively, use a minimum of 9 determinations over 3 different concentration levels (e.g., 3 concentrations with 3 replicates each) to cover the specified range [14] [15].

- Procedure:

- For Repeatability: A single analyst performs all determinations using the same equipment, reagents, and method within a short period (e.g., one day) [14] [3].

- For Intermediate Precision: The same procedure is repeated by different analysts, on different days, and/or using different instruments within the same laboratory [14] [15].

- Data Analysis: Calculate the standard deviation (SD) and relative standard deviation (RSD) for the set of measurements. The RSD of intermediate precision is typically larger than that of repeatability due to the incorporation of more sources of variation [14].

Protocol for Reproducibility

- Objective: To demonstrate that the analytical method yields consistent results when transferred to and used by different laboratories.

- Sample Preparation: A homogenous sample with a known or specified concentration is distributed to multiple participating laboratories.

- Procedure: Each laboratory follows the same, fully detailed analytical procedure. The study should involve at least two different laboratories, each with its own analysts, equipment, and environmental conditions [14] [3].

- Data Analysis: Collect the results from all participating laboratories. Calculate the overall standard deviation and RSD across all laboratories to quantify the method's reproducibility [14].

Relationships and Workflows

The following diagram illustrates the hierarchical relationship between the different measures of method reliability, from the most controlled to the broadest conditions.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Materials for Method Validation

This table details key reagents and materials required for executing the validation experiments described above.

{Table: Essential Research Reagents and Materials}

| Item | Function in Validation |

|---|---|

| Reference Standard (Analyte) | A purified substance used to prepare samples of known concentration for accuracy, linearity, and precision studies [15]. |

| Blank Matrix | The sample material without the analyte, used to demonstrate the method's specificity by proving no interference occurs [15]. |

| System Suitability Test (SST) Solutions | Reference solutions used to verify that the chromatographic system (or other instrumentation) is performing adequately before and during the analysis [15]. |

| Calibration Standards | A series of solutions with known concentrations of the analyte, used to establish the linearity and range of the method [15]. |

| Quality Control (QC) Samples | Samples prepared at low, medium, and high concentrations within the method's range, used to assess accuracy and precision during the validation runs [15]. |

In the rigorous world of analytical science, particularly within pharmaceutical development, the validation of methods is a cornerstone for generating reliable and meaningful data. Among the various performance characteristics evaluated, accuracy and trueness hold a position of critical importance, forming a direct link between experimental results and reality. As per the International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) guideline Q2(R1), accuracy is formally defined as "the closeness of agreement between the value which is accepted either as a a conventional true value or an accepted reference value and the value found," a concept sometimes also referred to as trueness [17].

This article explores the central role of accuracy within the broader context of method validation, objectively comparing it with the related, yet distinct, characteristic of precision. Framed within an ongoing scientific discourse on analytical method precision versus reproducibility research, this guide provides researchers and drug development professionals with a clear understanding of the protocols for demonstrating accuracy, how to interpret the data, and why it is a non-negotiable component of any "fit-for-purpose" analytical method [18].

Accuracy vs. Precision: The Fundamental Relationship

While often mentioned together, accuracy and precision describe different aspects of method performance. A clear understanding of this relationship is fundamental to method validation.

- Accuracy refers to the closeness of a measured value to a true or accepted reference value. It is a measure of correctness, often expressed as percent recovery [18] [2].

- Precision, on the other hand, expresses the closeness of agreement (degree of scatter) between a series of measurements obtained from multiple sampling of the same homogeneous sample. It is a measure of reproducibility under prescribed conditions [2].

A method can be precise (yielding consistent, repeatable results) without being accurate (all results are consistently wrong). Conversely, a method can be accurate on average without being precise, if results are scattered widely around the true value. The ideal method is both accurate and precise. This relationship is hierarchically structured within precision itself, which is commonly broken down into three measures [4] [2]:

- Repeatability (intra-assay precision): Results under the same operating conditions over a short interval of time.

- Intermediate Precision: Results within the same laboratory but with variations like different days, analysts, or equipment.

- Reproducibility: Results between different laboratories, as in collaborative studies.

The following diagram illustrates the core logical relationship between these key validation parameters, positioning accuracy and trueness within the broader validation framework:

Experimental Protocols for Assessing Accuracy

The demonstration of accuracy is not a one-size-fits-all process; its experimental design varies significantly depending on the type of analytical procedure (e.g., assay, impurity testing, dissolution).

Accuracy for Assay Methods

For the assay of drug substances or products, accuracy is typically assessed by analyzing samples of known concentration and calculating the percentage of recovery [17].

- Drug Substance: Accuracy is studied using a pure reference standard. Solutions are prepared at a minimum of three concentration levels (e.g., 80%, 100%, 120% of the test concentration), with triplicate preparations at each level. The calculated amount found is compared against the amount added [17] [2].

- Drug Product: Accuracy can be performed in two ways: by analyzing the drug product itself at different sample quantities corresponding to the accuracy levels, or by spiking a known amount of the Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API) into the placebo blend. The percentage recovery is then calculated, with acceptance criteria typically set between 98.0% and 102.0% [17].

Accuracy for Related Substances (Impurities)

Quantifying impurities with accuracy presents a unique challenge due to their low levels. The ICH guideline recommends studying accuracy from the reporting level (often the Limit of Quantitation - LOQ) to 120% of the specification level, with a minimum of three concentration levels and triplicate preparations at each level [17].

- Procedure: Known impurities are spiked into the drug substance or product (or a mixture of API and placebo). The accuracy solutions, for example, could be prepared at LOQ, 100% of the specification, and 120% of the specification.

- Calculation: The recovery of each impurity is calculated. The experimental design must ensure it covers both the release and shelf-life specification limits for the impurities [17].

Accuracy for Dissolution Testing

The demonstration of accuracy for dissolution methods ensures that the analytical procedure can correctly quantify the amount of drug released from the dosage form across the specified range.

- Immediate-Release (IR) Products: Accuracy is studied between ±20% over the specified range. For a specification of NLT 80% (Q), this would mean studying concentrations from 60% to 100% of the label claim. It is often recommended to extend this to 130% to cover potential super-potent units [17].

- Controlled-/Delayed-Release Products: The accuracy range should cover from the LOQ (practically replacing 0%) up to 110% or 130% of the label claim to encompass the entire release profile [17].

- Acceptance Criteria: Recovery for dissolution methods is generally wider than for assay, typically between 95.0% and 105.0% [17].

Data Presentation: Comparing Accuracy Across Method Types

The following table summarizes the key experimental parameters and acceptance criteria for assessing accuracy in different types of analytical methods, providing a clear, side-by-side comparison.

Table 1: Summary of Accuracy Experimental Protocols and Acceptance Criteria

| Method Type | Recommended Levels | Number of Replicates | Typical Acceptance Criteria (% Recovery) | Key Experimental Approach |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assay (Drug Substance/Product) | 80%, 100%, 120% of test conc. | Minimum 9 determinations (3 at each level) | 98.0 - 102.0 | Analysis of known purity standard or spiking API into placebo. |

| Related Substances (Impurities) | LOQ, 100%, 120% of specification | Minimum 9 determinations (3 at each level) | Varies by impurity level | Spiking known impurities into drug substance/product. |

| Dissolution Testing | ±20% over specified range (e.g., 60%-130%) | Triplicate preparations at each level | 95.0 - 105.0 | Using drug product or spiking API into dissolution medium/placebo. |

The workflow for planning and executing a method validation study, with accuracy as a central component, can be visualized as a sequential process. This ensures that the method's performance is thoroughly evaluated against predefined quality requirements.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The reliable execution of accuracy studies and method validation in general depends on the use of high-quality, well-characterized materials. The following table details key reagents and their critical functions.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Analytical Method Validation

| Reagent / Material | Function in Validation | Criticality for Accuracy |

|---|---|---|

| Certified Reference Standard | Serves as the accepted reference value for the analyte, providing the "conventional true value." | High. The entire accuracy study is dependent on the purity and certification of this material. |

| Placebo Formulation | Mimics the drug product matrix without the active ingredient. | High (for drug product). Used to assess specificity and to prepare spiked samples for recovery studies. |

| Known Impurity Standards | Pure substances of identified impurities used for spiking studies. | High (for impurity methods). Essential for determining the accuracy of impurity quantification. |

| High-Purity Solvents & Reagents | Used for preparation of mobile phases, standard and sample solutions. | Medium. Impurities can introduce interference and bias, affecting accuracy and specificity. |

| Characterized API (Drug Substance) | The active ingredient used for preparing accuracy samples and for system suitability. | High. The quality and stability of the API directly impact the results of recovery studies. |

Accuracy and trueness are not merely checkboxes in a method validation protocol; they are the critical link that ensures analytical data reflects the true quality of a drug substance or product. A method that lacks accuracy can lead to incorrect decisions, potentially compromising patient safety and product efficacy. While precision ensures that a method is reliable and consistent, accuracy confirms that it is also correct. In the broader thesis of precision versus reproducibility research, accuracy stands as the foundational parameter that gives meaning to all subsequent measurements. A method cannot be truly reproducible if it is not first accurate and precise within a single laboratory. Therefore, a rigorous, well-designed accuracy study, following established protocols and using appropriate reagents, remains a non-negotiable first step in demonstrating that an analytical method is truly fit-for-purpose.

In pharmaceutical development and biomedical research, the concepts of analytical method precision and reproducibility are foundational to research integrity. While related, they represent distinct layers of reliability: precision ensures that a method can consistently generate the same results under varying conditions within a single laboratory, while reproducibility confirms that different laboratories can achieve equivalent results using the same method [4]. This distinction is not merely academic; it forms the bedrock upon which drug approval, clinical decisions, and ultimately, public trust in science are built.

The scientific community currently faces a significant challenge known as the "replication crisis." A groundbreaking project in Brazil, involving a coalition of more than 50 research teams, recently surveyed a swathe of biomedical studies to double-check their findings, with dismaying results [19]. This follows earlier, alarming reports from industry: Bayer HealthCare found that only about 7% of target identification projects were fully reproducible, and an internal survey revealed that only 20-25% of projects had published data that aligned with in-house findings [20]. Similarly, Amgen scientists reported in 2012 that 89% of hematology and oncology results could not be replicated [20]. These failures directly impact public trust and the translational potential of research, underscoring the critical need for robust analytical methods.

Defining the Concepts: Precision vs. Reproducibility

A Comparative Framework

The following table outlines the core differences between intermediate precision and reproducibility, two key validation parameters often conflated but which serve unique purposes in the method validation lifecycle [4].

| Feature | Intermediate Precision | Reproducibility |

|---|---|---|

| Testing Environment | Same laboratory | Different laboratories |

| Primary Variables | Analyst, day, instrument | Lab location, equipment, analyst |

| Goal | Assess method stability under normal laboratory variations | Assess method transferability and global robustness |

| Routine Use | Yes, standard part of method validation | Not always; often part of collaborative inter-laboratory studies |

The Relationship in Practice

The following diagram illustrates the hierarchical relationship between precision (including its repeatability and intermediate precision components) and reproducibility within the overall framework of an analytical method's reliability.

As shown, intermediate precision measures the variability of analytical results when the same method is applied within the same laboratory but under different conditions, such as different analysts, instruments, or days [4]. Its purpose is to evaluate how consistent a method is under the typical day-to-day variations that occur in a single lab. For example, if one analyst runs a test today and another runs it two days later using different equipment, consistent results demonstrate good intermediate precision [4].

In contrast, reproducibility assesses the consistency of a method across different laboratories, representing the broadest evaluation of variability [4] [2]. It is often a part of inter-laboratory studies or collaborative trials and is critical for global drug development and regulatory submission. A method is considered reproducible if two different labs, using the same protocol on the same sample, can report similar results [4]. The term "ruggedness," which is falling out of favor with the ICH, is largely addressed under the concept of intermediate precision [2].

Experimental Protocols for Assessing Precision and Reproducibility

Standardized Method Validation Protocols

Regulatory guidelines, such as those from the International Council for Harmonisation (ICH), provide frameworks for validating analytical methods. The protocols for precision and reproducibility are well-established, though their implementation is evolving towards a more lifecycle-focused approach as seen in ICH Q14 [21] [22].

Protocol for Intermediate Precision [2]:

- Objective: To quantify the impact of within-laboratory variations on the analytical result.

- Experimental Design: An experimental design (e.g., involving two analysts) is used so that the effects of individual variables (analyst, instrument, day) can be monitored.

- Procedure: Two analysts independently prepare and analyze replicate sample preparations. Each analyst uses their own standards, solutions, and a different HPLC system.

- Data Analysis: The percentage difference in the mean values between the two analysts' results is calculated. This data is often subjected to statistical tests (e.g., a Student's t-test) to determine if there is a significant difference in the mean values obtained. Results are typically reported as the percent Relative Standard Deviation (%RSD).

Protocol for Reproducibility [2]:

- Objective: To demonstrate the method's performance across different laboratories.

- Experimental Design: A collaborative study is designed involving analysts from at least two different laboratories.

- Procedure: Each participating lab follows the same, detailed analytical procedure. Analysts prepare their own standards and solutions and use different equipment.

- Data Analysis: The standard deviation, relative standard deviation (%RSD), and confidence interval are calculated from the combined data from all laboratories. The percentage difference in the mean values between the labs must be within pre-defined specifications. Statistical analysis is used to determine if any significant differences exist between the labs' results.

Advanced and Risk-Based Approaches

Modern method development increasingly relies on Design of Experiments (DoE) and Quality-by-Design (QbD) principles [21] [23]. Instead of testing one variable at a time, DoE uses a structured matrix to efficiently study the simultaneous impact of multiple factors (e.g., pH, temperature, column type, analyst) on method performance [23]. This approach, aligned with ICH Q8 and Q9, provides a more robust understanding of the method's design space—the range of conditions within which it remains valid—thus enhancing both intermediate precision and the likelihood of successful reproducibility [21] [23].

Furthermore, the concept of lifecycle management (ICH Q12) is gaining traction. This involves continuous verification of critical method attributes linked to bias and precision throughout the method's life, moving beyond a one-time validation event [21] [22]. Novel methodologies are being developed to estimate analytical method variability directly from data generated during the routine execution of the method, enabling ongoing performance verification [22].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Materials

The following table details essential materials and their functions in conducting robust analytical method validation, particularly for chromatographic methods.

| Tool/Reagent | Primary Function in Validation |

|---|---|

| Reference Standards | Well-characterized materials used as a benchmark for determining the accuracy, precision, and linearity of an analytical method. Their stability is critical [23]. |

| High-Quality Reagents & Solvents | Ensure consistency in sample and mobile phase preparation, minimizing baseline noise and variability that can affect precision, LOD, and LOQ. |

| Certified Chromatographic Columns | Provide reproducible separation performance. Different columns (lots or brands) may be tested during robustness and intermediate precision studies. |

| Mass Spectrometry (MS) Detectors | Provide unequivocal peak purity information, exact mass, and structural data, overcoming limitations of UV detection and greatly enhancing method specificity [2]. |

| Photodiode-Array (PDA) Detectors | Collect full spectra across a peak to evaluate peak purity and identify potential co-elution, which is critical for demonstrating method specificity [2]. |

| Cloud-Based LIMS (Laboratory Information Management System) | Enables real-time data sharing and integrity across global sites, supporting collaborative reproducibility studies and adhering to ALCOA+ principles for data governance [21]. |

Quantitative Data: The Scale of the Reproducibility Challenge

The following table summarizes findings from major reproducibility initiatives, highlighting the pervasive nature of this issue in biomedical research.

| Study / Initiative | Field / Focus | Reproducibility Failure Rate | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bayer HealthCare [20] | Preclinical Target Identification | 93% (Only 7% fully reproducible) | Internal findings aligned with published data in only 20-25% of projects; 65% had inconsistencies leading to termination. |

| Amgen [20] | Hematology & Oncology | 89% | Could not replicate the vast majority of published findings. |

| Brazilian Reproducibility Initiative [19] [20] | Brazilian Biomedical Science | 74% (Reported in preprint) | An unprecedented broad-scale effort, prompting calls for systemic reform. |

| Center for Open Science [20] | Preclinical Cancer Studies | 54% | A conservative estimate, as many scheduled studies were excluded and all replications required author assistance. |

| Stroke Preclinical Assessment Network [20] | Stroke Interventions | 83% | Only one of six tested potential interventions showed robust effects in multiple relevant stroke models. |

Consequences for Research Integrity and Public Trust

The failure to ensure reproducible and precise analytical methods has a cascading effect that extends far beyond the laboratory walls.

Erosion of Public Trust

When scientific findings are later retracted or fail to translate into real-world applications, public confidence in science erodes. This creates a vacuum that can be filled by misinformation. Industries with vested interests, such as tobacco and e-cigarettes, have historically exploited such vulnerabilities by manipulating science, funding misleading studies, and spreading disinformation to shape public discourse and delay policy action [24].

Economic and Ethical Costs

Irreproducible research represents a massive waste of public and private funding. Billions of dollars are spent pursuing false leads or re-investigating flawed findings, diverting resources from promising avenues. This directly impacts drug development, increasing costs and delaying the delivery of new therapies to patients [21] [20]. Furthermore, political interference, where political appointees override peer-review processes to cancel grants, further threatens scientific independence and integrity, demonstrating the fragility of the research ecosystem [24].

Systemic Pressures and Threats

The current research environment often prioritizes the quantity and novelty of publications over robust, repeatable science. This pressure, combined with:

- The rise of predatory journals that prioritize profit over rigorous peer review [24].

- Limited funding and career pressures, especially for early-career researchers [24].

- Insufficient training in rigorous analytical practices and conflict of interest [24].

creates a perfect storm that perpetuates the replication crisis.

Pathways to Solutions: Strengthening Scientific Integrity

Addressing this crisis requires a multi-faceted, systemic shift. Proposed solutions include:

- Mandatory Detailed Reporting: As suggested in reader responses to the replication crisis, journals could mandate a "Failure Analysis" section in supporting information, where authors detail critical parameters, tricks, and failure rates, providing invaluable context for replication [20].

- Independent Replication Supplements: A cornerstone experiment could be independently replicated by an external lab in an anonymized, randomized manner, with the report included as part of the manuscript submission [20].

- Increased Funding for Replication: Allocating a more significant portion of research budgets (e.g., 10% as a start) specifically for replication efforts, far exceeding the proposed 0.1% of the NIH budget [20].

- Cultural and Educational Shifts: Integrating advocacy for robust science, training on predatory publishing, and rewards for transparency into career development pathways for scientists [24]. Adopting a lifecycle approach to analytical methods, as envisioned in ICH Q14 and USP <1220>, ensures continuous method verification and improvement [21] [22].

The journey toward restoring unwavering trust in scientific findings begins with a steadfast commitment to the fundamental principles of analytical validation. By rigorously distinguishing between precision and reproducibility, implementing robust, risk-based experimental protocols, and fostering a culture that prioritizes transparency and verification, the scientific community can fortify its integrity and ensure that its work remains a reliable guide for future innovation and public health.

Implementing Precision and Reproducibility Testing in Your Laboratory Workflow

In the rigorous framework of analytical method validation, precision is a cornerstone, fundamentally describing the closeness of agreement between independent test results obtained under stipulated conditions [14]. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding and accurately determining the most fundamental layer of precision—repeatability, also known as intra-assay precision—is a critical first step in assuring method reliability. This measure of performance under identical, within-run conditions provides the baseline against which all other, more variable precision parameters are compared [25] [14].

While the broader thesis of analytical validation encompasses reproducibility (the precision between different laboratories) and intermediate precision (variations within a single laboratory over time), the repeatability study represents the controlled core of this hierarchy [26] [14]. It answers a deceptively simple question: What is the innate random error of my method when everything is kept as constant as humanly and technically possible? This guide provides a detailed, data-driven comparison of the components essential for designing and executing a robust intra-assay precision study, complete with experimental protocols and acceptance criteria, to serve as a definitive resource for the scientific community.

Precision Fundamentals: Defining the Spectrum of Measurement Variation

Precision in analytical chemistry is stratified into distinct levels, each evaluating different sources of random variation. The following diagram illustrates the hierarchy and scope of these key terms, from the most controlled to the broadest condition.

The diagram above shows that repeatability (intra-assay precision) constitutes the foundation, measuring variation under identical conditions within a single assay run [27] [14]. Intermediate precision introduces variables like different days, analysts, or instruments within the same laboratory, while reproducibility assesses the method's performance across different laboratories, representing the broadest measure of precision [26] [14]. It is crucial to distinguish precision from trueness (also known as accuracy); a method can be precise (all results are close together) without being true (all results are systematically offset from the true value), and vice versa [14].

Core Experimental Protocol for Intra-Assay Precision

A well-designed repeatability study is not a matter of chance but follows established, standardized protocols to ensure the results are meaningful and defensible.

Standardized Guidelines and Execution

The Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) EP05-A2 guideline provides a formal protocol for a thorough precision evaluation, which can be adapted specifically for the intra-assay (repeatability) component [25]. For a focused verification of repeatability, the less resource-intensive CLSI EP15-A2 protocol is often employed [25].

Typical Experimental Execution:

- Analytical Run: A single analytical run is performed.

- Replicates: A minimum of 6 to 9 replicate determinations of the same sample are conducted.

- Conditions: All determinations are performed under identical conditions: the same analyst, the same instrument, the same location, and within a short period of time (typically one run) [28] [14].

- Sample: The sample should be a homogeneous, stable material, such as a quality control pool, a processed patient sample, or a standard solution, analyzed at 100% of the test concentration [25] [14].

Data Calculation and Analysis

The results from the replicate analyses are used to calculate the standard deviation (SD) and the coefficient of variation (CV), which is the primary metric for reporting repeatability.

Key Formulas:

- Standard Deviation (SD): ( s = \sqrt{\frac{\sum(xi - \bar{x})^2}{n-1}} ) where ( xi ) is an individual result, ( \bar{x} ) is the mean of all results, and ( n ) is the number of replicates [25].

- Coefficient of Variation (CV%): ( CV = \frac{s}{\bar{x}} \times 100 ) [28] [25]. The CV expresses the relative standard deviation as a percentage of the mean, allowing for comparison across different concentrations and assays.

The following workflow details the steps from experimental setup to final result interpretation.

Quantitative Data and Acceptance Criteria

Establishing pre-defined acceptance criteria is mandatory for judging the success of a repeatability study. The following table summarizes common benchmarks and data from a practical example.

Table 1: Intra-Assay Precision Acceptance Criteria and Example Data

| Parameter | Typical Acceptance Criterion | Example Calculation (from 40 cortisol samples) |

|---|---|---|

| Intra-Assay CV | < 10% is generally acceptable [28]. For chromatographic assays, pharmacopoeias may specify stricter limits based on injections [14]. | Average Intra-Assay CV = 5.1% (calculated from individual duplicate CVs) [28]. |

| Inter-Assay CV | < 15% is generally acceptable [28]. This is a benchmark for intermediate precision, not repeatability. | Not Applicable (This is an intra-assay study) |

| Number of Replicates | Minimum of 6-9 determinations for a robust estimate [14]. | Each of the 40 samples was measured in duplicate (n=2) [28]. |

The example data in the table, drawn from a real-world immunoassay, shows performance well within the typical acceptance limit, indicating excellent repeatability [28]. It is critical to note that these criteria can vary based on the analytical technique, the analyte's concentration, and specific regulatory requirements. For instance, the pharmaceutical industry often follows ICH Q2(R1) guidelines, which mandate a minimum of 9 determinations (e.g., across 3 concentrations with 3 replicates each) or 6 determinations at 100% of the test concentration [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Executing a precise repeatability study requires high-quality materials and instruments. The following table details key research reagent solutions and their critical functions in the process.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Intra-Assay Precision Studies

| Item | Function / Importance |

|---|---|

| Homogeneous Sample | A stable, homogenous QC material, patient pool, or standard solution is fundamental. Any heterogeneity in the sample will artificially inflate the measured imprecision, invalidating the results [25]. |

| Calibrated Pipettes | Properly maintained and calibrated pipettes are non-negotiable for accurate liquid handling. Poor pipetting technique is a frequent source of poor intra-assay CVs [28]. |

| Quality Control (QC) Materials | While used for monitoring the assay, different QC levels can themselves be used as the test samples for precision studies. They provide known concentrations for assessing precision across the assay's range [25]. |

| Standardized Reagents | Using a single lot of reagents (calibrators, antibodies, buffers) throughout the entire intra-assay study is essential to prevent reagent variability from confounding the repeatability measurement. |

| Benzonase / Anti-Clumping Agents | Especially critical for viscous samples like saliva or cell lysates, these agents help homogenize samples, ensuring consistent aliquoting and pipetting, which leads to improved CVs [28] [26]. |

A meticulously designed intra-assay precision study is not merely a regulatory checkbox but a fundamental scientific practice that establishes the baseline performance of an analytical method. By adhering to standardized protocols like CLSI EP15-A2, utilizing appropriate homogeneous samples and calibrated equipment, and applying strict acceptance criteria (typically a CV of <10%), researchers can generate reliable and defensible data on method repeatability. This robust foundation of intra-assay precision is the essential first step in a comprehensive method validation hierarchy, ultimately supporting the development of safe, effective, and high-quality pharmaceuticals and diagnostic tools.

In the rigorous world of pharmaceutical development and quality control, demonstrating the reliability of analytical methods is not just good science—it is a regulatory requirement. Among the validation parameters, precision stands as a critical measure of method reliability, but it manifests differently across controlled and real-world conditions. This guide focuses specifically on intermediate precision, a fundamental tier of precision that quantifies the variability inherent to normal laboratory operations when an analytical procedure is performed over an extended period by different analysts using different instruments [29] [14].

Understanding intermediate precision is essential because it bridges the gap between the ideal conditions of repeatability and the broad variability of reproducibility. While repeatability captures the smallest possible variation under identical, short-term conditions, and reproducibility reflects the precision between different laboratories, intermediate precision represents the realistic "within-lab" variability [3] [30]. It answers a practical question: How much can results vary when the same method is used routinely within our laboratory, accounting for inevitable changes like different staff, equipment, and days? This assessment is typically expressed statistically as a relative standard deviation (RSD%), providing a normalized measure of scatter that accounts for random errors introduced by these operational variables [29] [2].

Precision Tier Comparison: Repeatability, Intermediate Precision, and Reproducibility

To fully grasp the role of intermediate precision, it must be contextualized within the hierarchy of precision measures. The following table provides a clear, comparative overview of these three key tiers.

Table 1: Comparison of the Three Tiers of Analytical Method Precision

| Feature | Repeatability | Intermediate Precision | Reproducibility |

|---|---|---|---|

| Definition | Closeness of results under identical conditions over a short time [3] [14] | Closeness of results within a single laboratory under varying routine conditions [29] | Precision between measurement results obtained in different laboratories [3] [2] |

| Alternative Names | Intra-assay precision [14] | Within-laboratory reproducibility, Inter-assay precision [29] | Between-lab reproducibility [3] |

| Key Variations Included | None; same analyst, instrument, and day [14] | Different analysts, days, instruments, reagent batches, and columns [29] [3] | Different laboratories, analysts, equipment, and environmental conditions [14] [2] |

| Primary Scope | Best-case scenario, inherent method noise [3] | Realistic internal lab variability [30] | Broadest variability, method transferability [2] |

| Typical RSD | Lowest | Higher than repeatability [29] | Highest |

The relationship between these concepts can be visualized as a progression of increasing variability, as shown in the following workflow.

Core Experimental Protocol for Assessing Intermediate Precision

The evaluation of intermediate precision is not a single, fixed experiment but a structured process designed to capture the sources of variability expected during the method's routine use. The goal is to quantify the combined impact of multiple changing factors within the laboratory environment.

Experimental Design and Data Collection

The International Conference on Harmonisation (ICH) Q2(R1) guideline suggests two primary approaches for designing an intermediate precision study [29]:

- Individual Factor Variation: Systematically altering one factor at a time (e.g., two analysts on two different days, each using a different instrument).

- Matrix Approach (Kojima Design): A more efficient design that combines all potential variations—such as different analysts, days, and instruments—into a single, holistic experiment comprising, for example, six runs that cover all aspects together [29] [14].

A typical dataset for such a study involves multiple measurements (e.g., 6 replicates) for each unique combination of conditions. The collected data is then aggregated to calculate the overall intermediate precision.

Table 2: Example Data Structure from an Intermediate Precision Study on Drug Content [29]

| Day | Analyst | Instrument | Measurement 1 (mg) | Measurement 2 (mg) | Measurement 3 (mg) | Mean (mg) | SD (mg) | RSD (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Analyst 1 | Instrument 1 | 1.44 | 1.46 | 1.45 | 1.46 | 0.019 | 1.29 |

| 2 | Analyst 2 | Instrument 1 | 1.49 | 1.48 | 1.49 | 1.48 | 0.008 | 0.55 |

| Overall (n=12) | 1.47 | 0.020 | 1.38 |

Calculation and Statistical Analysis

The core of intermediate precision is its standard deviation, which accounts for variance within and between the different experimental conditions.

- Formula: The intermediate precision standard deviation (σIP) can be calculated using the formula: σIP = √(σ²within + σ²between) [30]. Here, σ²within is the variance within each set of conditions (e.g., the variance of Analyst 1's results), and σ²between is the variance introduced by the changing factors themselves (e.g., the variance between the mean results of Analyst 1 and Analyst 2).

- Result Expression: The final result is most commonly reported as the Relative Standard Deviation (RSD%) or Coefficient of Variation, which is calculated as (σIP / Overall Mean) × 100% [29] [2]. This normalized value allows for easy comparison across different methods and concentration levels.

- Data Interpretation: As seen in Table 2, even if individual analysts are precise, a consistent difference between them (bias) or a significant instrument effect will lead to a larger overall RSD% for intermediate precision compared to any single analyst's repeatability RSD% [29]. Statistical analysis using variance components can further decompose the total variability into portions attributable to the analyst, day, instrument, and random error [31].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Conducting a robust intermediate precision study requires more than a good design; it relies on high-quality materials and well-characterized instruments. The following table details key resources essential for these experiments.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions and Materials for Precision Studies

| Item | Function in Intermediate Precision Assessment |

|---|---|

| Reference Standard | A highly pure and well-characterized substance used to prepare calibration standards and evaluate the method's accuracy and linearity across the intended range [2]. |

| Chromatographic Column | A critical component in HPLC methods; using columns from different batches is recommended during validation to assess the method's robustness to this variation [29] [3]. |

| Reagent Batches | Different lots of solvents, buffers, and other chemicals are used to ensure the method's performance is not adversely affected by normal variability in supply materials [3]. |

| Calibrated Instruments | Analytical balances, pH meters, and the main instruments (e.g., HPLC, GC) themselves must be properly qualified and calibrated. Using different instruments of the same model is part of the validation [29] [32]. |

A thorough assessment of intermediate precision is indispensable for demonstrating that an analytical method is fit for its intended purpose in a real-world laboratory setting. By intentionally incorporating and quantifying the effects of variations in analyst, instrument, and day, scientists and drug development professionals can build a strong case for the method's robustness. This not only ensures the generation of reliable data for quality control and regulatory submissions but also provides confidence in the consistency of the analytical results throughout the method's lifecycle. In the broader thesis of analytical validation, intermediate precision stands as the crucial link that proves a method can deliver consistent performance not just under ideal conditions, but under the normal, variable conditions of daily laboratory practice.

Reproducibility is a cornerstone of the scientific method, yet achieving consistent results across different laboratories remains a significant challenge. Inter-laboratory collaborative trials are a powerful tool to assess and ensure the reliability of analytical methods, differentiating between internal precision (the closeness of agreement between independent test results under stipulated conditions) and reproducibility (the ability to obtain the same results when the analysis is performed in different laboratories, by different analysts, using different equipment) [33]. This guide compares protocols from recent, successful reproducibility studies, providing a structured framework for researchers and drug development professionals to plan their own collaborative trials.

Key Concepts: Precision vs. Reproducibility

Understanding the distinction between precision and reproducibility is critical for designing a robust collaborative study.

- Precision: This refers to the consistency of results within a single laboratory. It is measured by the closeness of agreement between multiple test results on the same sample, obtained under the same controlled conditions. High precision indicates low internal variability and is the foundation for reliable method performance [33].

- Reproducibility: This is a more rigorous test, assessing the consistency of results between different laboratories. It measures the ability of different analysts, using different equipment and locations, to replicate the findings of an original study using the same standardized method. Reproducibility is the ultimate validation of a method's robustness and real-world applicability [33] [34].

Comparative Analysis of Reproducibility Studies

The following table summarizes the design and outcomes of several inter-laboratory studies, highlighting the approaches used to ensure reproducibility.

Table 1: Comparison of Recent Inter-Laboratory Reproducibility Studies

| Study Focus & Reference | Participating Laboratories | Key Standardized Elements | Primary Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plant-Microbiome Research [34] [35] | 5 international labs | Fabricated ecosystems (EcoFAB 2.0), synthetic bacterial communities (SynComs), seeds, filters, and a detailed written/video protocol. | Consistent, inoculum-dependent changes in plant phenotype, root exudate composition, and final bacterial community structure were observed across all labs. |

| Biocytometry Workflow [36] | 10 primarily undergraduate institutions (PUIs) | Reagents, standardized protocols (written and video), and sample types were provided by the industry partner, Sampling Human. | Data generated by undergraduate students was statistically comparable to that produced by PhD-level scientists, demonstrating the workflow's reproducibility. |

| Toxicogenomics Datasets [37] | 3 test centres (TCs) | A standard operating procedure (SOP) for cell culture, chemical exposure, RNA extraction, and microarray analysis. | A common subset of responsive genes was identified by all laboratories, supporting the robustness of toxicogenomics for regulatory assessment. |

| Generic Drug Reverse Engineering [33] | (Theoretical framework for multi-site development) | Formulation "recipe" (API & excipients), analytical methods, and manufacturing process (via Quality by Design principles). | Ensures that a generic drug product is a mirror image of the innovator product, enabling regulatory approval via bioequivalence. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Collaborative Trials

Drawing from the successful studies above, here are detailed methodologies for key aspects of inter-laboratory testing.

Protocol for a Multi-Laboratory Plant-Microbiome Study

This protocol is adapted from the EcoFAB study, which achieved high reproducibility across five labs [34].

Objective: To test the replicability of synthetic community (SynCom) assembly, plant phenotypic responses, and root exudate composition using standardized fabricated ecosystems.

Materials:

- Fabricated Ecosystems (EcoFAB 2.0 devices): Sterile, controlled habitats distributed from a central lab [34].

- Seeds: Batch-matched seeds of the model grass Brachypodium distachyon from a single source.

- Synthetic Microbial Communities (SynComs): Cryopreserved stocks of defined bacterial strains (e.g., a 17-member SynCom and a 16-member variant lacking a key colonizer) sourced from a public biobank like DSMZ [34].

- Growth Medium: A standardized, sterile nutrient medium.

Methodology:

- Setup and Planting: All laboratories prepare EcoFAB devices under sterile conditions. Surface-sterilized seeds are germinated and aseptically transferred into the devices containing the standardized growth medium [34].

- Inoculation: At a specified growth stage (e.g., upon root establishment), devices are inoculated with either:

- The full SynCom.

- A variant SynCom (e.g., missing a key strain).

- A sterile mock inoculant as a control [34].

- Plant Growth: Plants are grown in controlled environmental chambers with standardized light, temperature, and humidity conditions as defined in the shared protocol.

- Sample Collection: At the endpoint of the experiment, all labs collect:

- Plant biomass (shoot and root) for phenotypic analysis.

- Root samples for microbial community analysis via 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing.

- Filtered growth media for metabolomic analysis via LC-MS/MS [34].

- Centralized Analysis: To minimize analytical variation, all samples for 'omics analyses (sequencing, metabolomics) are sent to a single, designated laboratory for processing [34].

- Data Integration: The organizing laboratory compiles and analyzes all phenotypic and molecular data to assess inter-laboratory consistency.

Protocol for Beta-Testing an Analytical Workflow with Multiple Institutions

This protocol is modeled on the collaboration between Sampling Human and multiple undergraduate institutions [36].

Objective: To assess the reproducibility and user-friendliness of a new biocytometry workflow for single-cell analysis across users with varying expertise.

Materials:

- Testing Kits: Pre-packaged kits containing all necessary reagents, such as DOT bioparticles for detecting specific cell surface markers [36].

- Standardized Protocols: Detailed written instructions accompanied by video tutorials demonstrating each step of the workflow.

- Reference Samples: Blind test samples with known characteristics (e.g., defined concentrations of target cells) for participants to analyze.

Methodology:

- Training and Onboarding: The lead company or lab holds virtual meetings with all participating faculty and students to review the protocol, required equipment (e.g., plate readers), and data acquisition settings [36].

- Experimental Execution: Each participating institution follows the standardized protocols to process the provided samples using their own locally available equipment.

- Troubleshooting Support: A central communication channel (e.g., dedicated email, forum) is established for participants to report technical challenges and receive support.

- Data Submission: Participants submit their raw data (e.g., plate reader outputs) to the lead organization for centralized, uniform analysis.

- Statistical Comparison: The lead organization performs a blinded analysis, comparing the data generated by the participants against benchmark data generated by expert PhD-level scientists using statistical methods like two-way ANOVA to check for significant differences in detectability between user groups [36].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Materials for Reproducibility

The success of a collaborative trial hinges on the careful selection and standardization of materials. The table below lists key reagents and solutions used in the featured studies.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Reproducibility Studies

| Item | Function in the Experiment | Example from Search Results |

|---|---|---|

| Synthetic Microbial Community (SynCom) | A defined mixture of microbial strains used to limit complexity while retaining functional diversity, enabling the study of community assembly and host-microbe interactions. | A 17-member bacterial community from a grass rhizosphere, available via a public biobank (DSMZ) [34]. |

| Diagnostics on Target (DOT) Bioparticles | Functional particles used in biocytometry workflows to target and report the presence of specific cell types based on surface markers, enabling single-cell analysis. | Bioparticles targeting EpCAM-positive cells among a background of EpCAM-negative cells [36]. |

| Fabricated Ecosystem (EcoFAB) | A sterile, standardized laboratory habitat that controls biotic and abiotic factors, providing a replicable environment for studying microbiome interactions. | The EcoFAB 2.0 device used for growing the model grass Brachypodium distachyon under gnotobiotic conditions [34]. |

| Standardized Growth Medium | A chemically defined medium that provides consistent nutritional and environmental conditions, eliminating variability from natural or complex substrates. | Murashige and Skoog (MS) medium used in the plant-microbiome study [34]. |

Workflow Visualization for Study Planning

The following diagram illustrates the logical sequence and decision points for planning a successful inter-laboratory reproducibility study.

Planning a Reproducibility Study

The experimental phase of a collaborative trial follows a structured path from setup to analysis, as shown below.

Standardized Experimental Workflow