Sequential Simplex Method: Basic Principles, Modern Applications, and Optimization for Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive guide to the Sequential Simplex Method, a powerful optimization algorithm widely used in scientific and industrial research.

Sequential Simplex Method: Basic Principles, Modern Applications, and Optimization for Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to the Sequential Simplex Method, a powerful optimization algorithm widely used in scientific and industrial research. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it covers foundational principles from its geometric interpretation to advanced methodological implementations. The content explores practical applications in analytical chemistry and process optimization, addresses common troubleshooting scenarios and optimization techniques, and offers a comparative analysis with other optimization strategies. By synthesizing theoretical knowledge with practical insights, this article serves as an essential resource for efficiently optimizing complex experimental processes in biomedical and clinical research.

Understanding the Sequential Simplex Method: Core Concepts and Historical Development

Within the broader context of research on the sequential simplex method's basic principles, a precise understanding of its foundational geometry is paramount. The simplex algorithm, developed by George Dantzig in 1947, is a cornerstone of mathematical optimization for solving linear programming problems [1] [2]. Its efficiency and widespread adoption in fields like business analytics, supply chain management, and economics stem from a clean and powerful geometric intuition [3]. This guide provides an in-depth examination of the simplex method's geometric interpretation and its associated terminology, framing these core concepts for an audience of researchers and drug development professionals who utilize these techniques in complex, data-driven environments.

Core Terminology and Standard Form

To establish a common language for researchers, we begin by defining the essential terminology used in conjunction with the simplex algorithm.

- Linear Program (LP): A mathematical problem concerned with minimizing or maximizing a linear objective function subject to a set of linear constraints [3].

- Objective Function: The linear function, typically written as ( \bm{c}^T\bm{x} ), that is to be optimized [1] [4].

- Constraints: The set of linear inequalities or equations that define the feasible region. The general form is ( A\bm{x} \leq \bm{b} ) and ( \bm{x} \geq 0 ) [1].

- Slack Variable: A variable added to an inequality constraint to transform it into an equality. For a constraint ( \bm{a}i^T \bm{x} \leq bi ), the slack variable ( si ) satisfies ( \bm{a}i^T \bm{x} + si = bi ) and ( s_i \geq 0 ) [1] [2].

- Basic Feasible Solution: A solution that corresponds to a vertex (extreme point) of the feasible polytope [1].

- Pivoting: The algebraic operation of swapping a non-basic variable (entering the basis) with a basic variable (leaving the basis), which corresponds to moving from one vertex to an adjacent vertex [1] [4].

- Simplex Tableau (or Dictionary): A tabular array used to perform the simplex algorithm steps. It organizes the coefficients of the variables and the objective function for efficient pivoting [1] [2] [4].

A crucial step in applying the simplex algorithm is to cast the linear program into a standard form. The algorithm accepts a problem in the form:

[ \begin{aligned} \text{minimize } & \bm{c}^T \bm{x} \ \text{subject to } & A\bm{x} \preceq \bm{b} \ & \bm{x} \succeq \bm{0} \end{aligned} ]

It is important to note that any linear program can be converted to this standard form through the use of slack variables, surplus variables, and by replacing unrestricted variables with the difference of two non-negative variables [1] [4]. For maximization problems, one can simply maximize ( -\bm{c}^T\bm{x} ) instead [3].

Table 1: Methods for Converting to Standard Form

| Component to Convert | Method for Standard Form Conversion |

|---|---|

| Inequality Constraint (( \leq )) | Add a slack variable: ( \bm{a}i^T \bm{x} + si = b_i ) [1] |

| Inequality Constraint (( \geq )) | Subtract a surplus variable and add an artificial variable [1] |

| Unrestricted Variable (( z )) | Replace with ( z = z^+ - z^- ) where ( z^+, z^- \geq 0 ) [1] |

| Maximization Problem | Convert to minimization: maximize ( \bm{c}^T\bm{x} ) = minimize ( (-\bm{c}^T\bm{x}) ) [3] |

Geometric Interpretation of the Simplex Method

The geometric interpretation of the simplex algorithm provides the intuitive foundation upon which its operation is built. This section elucidates the key geometric concepts.

The Feasible Region as a Convex Polytope

The solution space defined by the constraints ( A\bm{x} \leq \bm{b} ) and ( \bm{x} \geq 0 ) forms a geometric object known as a convex polytope [3]. A polytope is the multi-dimensional generalization of a polygon; it is a geometric object with flat sides. In two dimensions, the feasible region is a convex polygon. The property of convexity is critical: for any two points within the shape, the entire line segment connecting them also lies within the shape [3]. Each linear constraint defines a half-space, and the feasible region is the intersection of all these half-spaces, which always results in a convex set [1].

Extreme Points and the Optimal Solution

A fundamental observation that makes the simplex method efficient is that if a linear program has an optimal solution that is bounded and feasible, then that optimum occurs at least at one extreme point (vertex) of the feasible polytope [1] [3]. This reduces an infinite search space (all points in the polytope) to a finite one (the finite number of vertices). The following table summarizes the key geometric and algebraic equivalents:

Table 2: Geometric and Algebraic Equivalents in the Simplex Method

| Geometric Concept | Algebraic Equivalent |

|---|---|

| Feasible Region / Convex Polytope | The set of all vectors ( \bm{x} ) satisfying ( A\bm{x} = \bm{b}, \bm{x} \geq 0 ) [3] |

| Extreme Point (Vertex) | Basic Feasible Solution [1] [3] |

| Edge of the Polytope | A direction of movement from one basic feasible solution to an adjacent one [1] |

| Moving along an Edge | A pivot operation: exchanging a basic variable with a non-basic variable [1] [4] |

The Algorithm as a Vertex-to-Vertex Walk

The simplex algorithm operates by walking along the edges of the polytope from one vertex to an adjacent one. It begins at an initial vertex (often the origin, if feasible) [4]. At the current vertex, the algorithm examines the edges that emanate from it. The second key observation is that if a vertex is not optimal, then there exists at least one edge leading from it to an adjacent vertex such that the objective function value is strictly improved (for a maximization problem) [3]. The algorithm selects such an edge, moves along it to the next vertex, and repeats the process. This continues until no improving edge exists, at which point the current vertex is the optimal solution [1] [3].

The Simplex Algorithm: A Detailed Methodology

This section outlines the experimental or computational protocol for implementing the simplex algorithm, providing a step-by-step methodology that mirrors the geometric intuition with algebraic operations.

Initialization and Feasibility Check

The first step is to formulate the linear program in standard form and check for initial feasibility. For many problems, the origin (( \bm{x} = \bm{0} )) is a feasible starting point. The algorithm checks that ( A\bm{0} \preceq \bm{b} ), which simplifies to ( \bm{b} \succeq \bm{0} ) [4]. If the origin is not feasible, a Phase I simplex algorithm is required to find an initial basic feasible solution, which involves solving an auxiliary linear program [1].

Constructing the Initial Tableau

Once a basic feasible solution is identified, the initial simplex tableau (or dictionary) is constructed. For a problem with n original variables and m constraints, the initial dictionary is an ( (m+1) \times (n+m+1) ) matrix [4]:

[

D = \left[\begin{array}{ccc}

0 & \bar{\bm{c}}^T \

\bm{b} & -\bar{A}

\end{array}\right]

]

where ( \bar{A} = [A \quad Im] ) and ( \bar{\bm{c}}^T = [\bm{c}^T \quad \bm{0}^T] ) [4]. The identity matrix ( Im ) corresponds to the columns of the slack variables added to the constraints.

The Pivoting Operation Protocol

Pivoting is the core mechanism that moves the solution from one vertex to an adjacent one. The following workflow details this operation, which is also visualized in the diagram below.

Diagram 1: Simplex Algorithm Pivoting Workflow

The logical flow of the pivoting operation is as follows:

- Select the Entering Variable: Scan the objective row (the top row of the tableau, ignoring the first element) for the first negative value. The variable corresponding to this column (the pivot column) is the entering variable, as it will enter the basis and become a basic variable [2] [4]. This choice corresponds to selecting an edge along which the objective function will improve.

- Check for Unboundedness: If all entries in the pivot column (excluding the objective row) are non-negative, then the problem is unbounded; the objective function can improve indefinitely along that edge, and the algorithm terminates [4].

- Select the Leaving Variable via the Minimum Ratio Test: If the pivot column has negative entries, the leaving variable is determined by the minimum ratio test. For each row ( i ) (from 1 to m), calculate the ratio ( \frac{-D{i,0}}{D{i,j}} ), where ( j ) is the pivot column index. The row that yields the smallest non-negative ratio is the pivot row. The current basic variable for this row is the leaving variable [2] [4]. This test ensures the solution remains feasible by identifying the first binding constraint along the chosen edge.

- Perform the Pivot Operation: The pivot element is the intersection of the pivot column and pivot row. Execute row operations on the tableau so that the pivot column becomes a negative elementary vector (all zeros except for a -1 in the pivot row) [1] [4]. This algebraic manipulation updates the entire system of equations and the objective function to reflect the new basic feasible solution.

- Check for Optimality: After pivoting, examine the objective row. If there are no more negative entries in the objective row (for a maximization problem presented in this tableau format), the current solution is optimal. Otherwise, return to Step 1 [2].

Termination and Solution Extraction

Upon termination, the optimal solution can be read directly from the final tableau. The variables are found by looking at the columns that form a permuted identity matrix. The variables corresponding to these columns (the basic variables) take the value in the first column of their respective rows. All other (non-basic) variables are zero [2]. The value of the objective function at the optimum is found in the top-left corner of the tableau [4].

The Researcher's Toolkit for Simplex Implementation

For researchers implementing the simplex algorithm, either for theoretical study or application in domains like drug development, the following toolkit is essential.

Table 3: Essential Components for a Simplex Algorithm Solver

| Component / Concept | Function and Role in the Algorithm |

|---|---|

| Matrix Manipulation Library (e.g., NumPy in Python) | Performs the linear algebra operations (row operations, ratio tests) required for the pivoting steps efficiently [4]. |

| Tableau (Dictionary) Data Structure | A matrix (often a 2D array) that tracks the current state of the constraints, slack variables, and objective function [4]. |

| Bland's Rule | An anti-cycling rule that selects the entering and leaving variables based on the smallest index in case of ties during selection. This ensures the algorithm terminates, avoiding infinite loops [4]. |

| Phase I Simplex Method | A protocol to find an initial basic feasible solution when the origin is not feasible. It sets up and solves an auxiliary linear program to initialize the main algorithm [1]. |

| Sensitivity Analysis (Post-Optimality Analysis) | A technique used after finding the optimum to determine how sensitive the solution is to changes in the coefficients ( \bm{c} ), ( A ), or ( \bm{b} ). |

Advanced Context: Interior Point Methods

While the simplex method traverses the exterior of the feasible polytope, a different class of algorithms known as Interior Point Methods (IPMs) was developed. Triggered by Narendra Karmarkar's seminal 1984 paper, IPMs travel through the interior of the feasible region [5]. They have been proven to have polynomial worst-case time complexity and can be more efficient than the simplex method on very large-scale problems, making them an important alternative in modern optimization solvers [5].

The sequential simplex method represents a cornerstone of direct search optimization, enabling the minimization or maximization of objective functions where derivative information is unavailable or unreliable. Within the broader context of sequential simplex method basic principles research, the historical evolution from the fixed-shaped simplex of Spendley, Hext, and Himsworth to the adaptive algorithm of Nelder and Mead marks a critical transition that expanded the practical applicability of these techniques. For researchers and drug development professionals, this evolutionary pathway illustrates how algorithmic adaptability can dramatically enhance optimization performance in complex experimental environments such as response surface methodology, formulation development, and pharmacokinetic modeling.

The fundamental principle underlying simplex-based methods involves using a geometric structure—a simplex—to explore the parameter space. A simplex in n-dimensional space consists of n+1 vertices that form the simplest possible polytope, such as a triangle in two dimensions or a tetrahedron in three dimensions [6]. The sequential progression of the simplex through the parameter space, based solely on function evaluations at its vertices, creates a robust heuristic search strategy that has proven particularly valuable in pharmaceutical applications where experimental noise, discontinuous response surfaces, and resource-intensive function evaluations are common challenges.

Historical Context and Algorithmic Evolution

The Foundational Work of Spendley, Hext, and Himsworth

The genesis of simplex-based optimization methods emerged in 1962 with the seminal work of Spendley, Hext, and Himsworth, who introduced the first simplex-based direct search method [6]. Their approach utilized a regular simplex where all edges maintained equal length throughout the optimization process. This geometric regularity imposed significant constraints on the algorithm's behavior: the simplex could change size through reflection away from the worst vertex or shrinkage toward the best vertex, but its shape remained invariant because the angles between edges were constant throughout all iterations [6].

This fixed-shape characteristic presented both advantages and limitations. The method maintained numerical stability and predictable convergence patterns, but lacked the adaptability to respond to the local topography of the response surface. In drug formulation optimization, for instance, this rigidity could lead to inefficient performance when navigating elongated valleys or ridges in the response surface—common scenarios in pharmaceutical development where factor effects often exhibit different scales and interactions.

Table: Key Characteristics of the Spendley, Hext, and Himsworth Simplex Method

| Feature | Description | Implication for Optimization |

|---|---|---|

| Simplex Geometry | Regular shape with equal edge lengths | Predictable search pattern but limited adaptability |

| Allowed Transformations | Reflection away from worst vertex and shrinkage toward best vertex | Size changes possible but shape remains constant |

| Shape Adaptation | No shape change during optimization | Inefficient for anisotropic response surfaces |

| Convergence Behavior | Methodical but potentially slow for complex surfaces | Reliable but may require many function evaluations |

The Nelder-Mead Enhancement: An Adaptive Simplex

In 1965, John Nelder and Roger Mead published their seminal modification that fundamentally transformed the capabilities of simplex-based optimization [6] [7]. Their critical insight was that allowing the simplex to adapt not only its size but also its shape would enable more efficient navigation of complex response surfaces. Their algorithm could "elongate down long inclined planes, changing direction on encountering a valley at an angle, and contracting in the neighbourhood of a minimum" [6].

This adaptive capability was achieved through two additional transformation operations—expansion and contraction—that worked in concert with reflection to create a more responsive optimization strategy. The Nelder-Mead method could thus dynamically adjust to the local landscape, stretching along favorable directions and contracting transversely to hone in on optimal regions. For drug development researchers, this translated to more efficient optimization of complex multivariate systems such as media formulation, chromatography conditions, and synthesis parameters, where the number of experimental runs directly impacts project timelines and resource allocation.

Table: Comparative Analysis of Simplex Method Evolution

| Characteristic | Spendley, Hext, and Himsworth (1962) | Nelder and Mead (1965) |

|---|---|---|

| Simplex Flexibility | Fixed shape | Adaptive shape and size |

| Transformations | Reflection, shrinkage | Reflection, expansion, contraction, shrinkage |

| Parameter Count | 2 (reflection, shrinkage) | 4 (α-reflection, β-contraction, γ-expansion, δ-shrinkage) |

| Response to Landscape | Uniform regardless of topography | Elongates down inclined planes, contracts near optima |

| Implementation Complexity | Relatively simple | More complex decision logic |

| Performance on Anisotropic Surfaces | Often inefficient | Generally more efficient |

The Nelder-Mead Algorithm: Technical Implementation

Core Algorithmic Structure

The Nelder-Mead algorithm operates through an iterative sequence of transformations applied to a working simplex, with each iteration consisting of several clearly defined steps. The method requires only function evaluations at the simplex vertices, making it particularly valuable for optimizing experimental systems where objective function measurements come from physical experiments rather than computational models [6].

The algorithm begins by ordering the simplex vertices according to their function values:

[ f(x1) \leq f(x2) \leq \cdots \leq f(x_{n+1}) ]

where (x1) represents the best vertex (lowest function value for minimization) and (x{n+1}) represents the worst vertex (highest function value) [7]. The method then calculates the centroid (c) of the best side (all vertices except the worst):

[ c = \frac{1}{n} \sum{j \neq h} xj ]

The subsequent transformation phase employs four possible operations, each controlled by specific coefficients: reflection (α), expansion (γ), contraction (β), and shrinkage (δ) [6]. The standard values for these parameters, as originally proposed by Nelder and Mead, are α=1, γ=2, β=0.5, and δ=0.5 [6] [7].

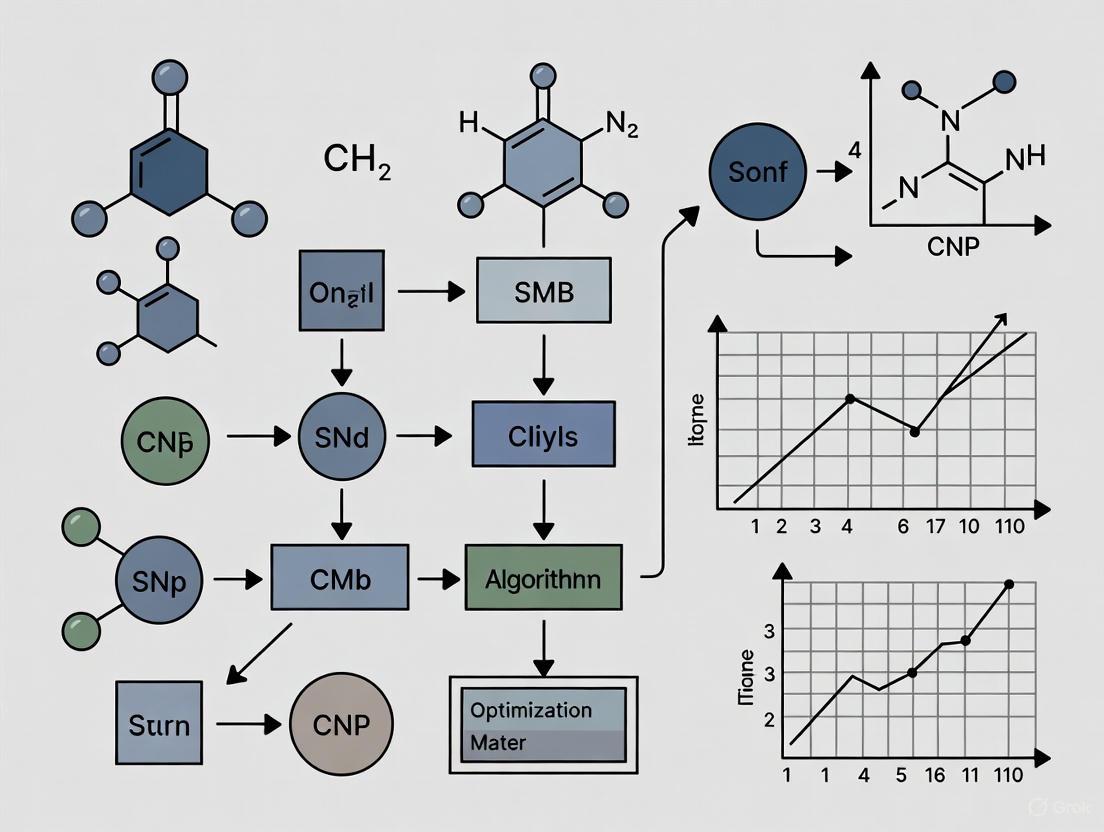

Diagram 1: The Nelder-Mead algorithm workflow showing the logical sequence of operations and decision points during each iteration.

Transformation Operations and Geometric Interpretation

The Nelder-Mead method employs four principal transformation operations that enable the simplex to adapt to the response surface topography:

Reflection: The worst vertex (x{n+1}) is reflected through the centroid of the opposite face to generate point (xr) using (xr = c + α(c - x{n+1})) with α=1 [6] [7]. If the reflected point represents an improvement over the second-worst vertex but not better than the best ((f(x1) ≤ f(xr) < f(x_n))), it replaces the worst vertex.

Expansion: If the reflected point is better than the best vertex ((f(xr) < f(x1))), the algorithm expands further in this promising direction using (xe = c + γ(xr - c)) with γ=2 [7]. If the expanded point improves upon the reflected point ((f(xe) < f(xr))), it is accepted; otherwise, the reflected point is accepted.

Contraction: When the reflected point is not better than the second-worst vertex ((f(xr) ≥ f(xn))), a contraction operation is performed. If (f(xr) < f(x{n+1})), an outside contraction generates (xc = c + β(xr - c)); otherwise, an inside contraction creates (xc = c + β(x{n+1} - c)) with β=0.5 [7]. If the contracted point improves upon the worst vertex, it is accepted.

Shrinkage: If contraction fails to produce a better point, the simplex shrinks toward the best vertex by replacing all vertices except (x1) with (xi = x1 + δ(xi - x_1)) using δ=0.5 [7].

Diagram 2: Geometric interpretation of reflection and expansion operations showing the movement of the simplex in relation to the centroid and worst vertex.

Experimental Methodology and Research Reagents

Implementation Protocols for Pharmaceutical Applications

Implementing the Nelder-Mead algorithm effectively in drug development research requires careful consideration of several methodological aspects. The initial simplex construction significantly influences algorithm performance, with two primary approaches employed:

Right-angled simplex: Constructed using coordinate axes with (xj = x0 + hj ej) for (j = 1, \ldots, n), where (hj) represents the step size in the direction of unit vector (ej) [6]. This approach aligns the simplex with the parameter axes, which may be advantageous when factors have known independent effects.

Regular simplex: All edges have identical length, creating a symmetric starting configuration [6]. This approach provides unbiased initial exploration when little prior information exists about factor interactions.

For pharmaceutical optimization studies, factor scaling proves critical to algorithm performance. Factors should be normalized so that non-zero input values maintain similar orders of magnitude, typically between 1-10, to prevent numerical instabilities and ensure balanced progression across all dimensions [8]. Similarly, feasible solutions should ideally have non-zero entries of comparable magnitude to promote stable convergence.

Termination criteria represent another crucial implementation consideration. Common approaches include testing whether the simplex has become sufficiently small based on vertex dispersion, or whether function values at the vertices have become close enough (for continuous functions) [6]. In experimental optimization, practical constraints such as maximum number of experimental runs or resource limitations often provide additional termination conditions.

Research Reagent Solutions for Experimental Optimization

Table: Essential Methodological Components for Simplex Optimization in Pharmaceutical Research

| Component | Function | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Initial Simplex Design | Provides starting configuration for optimization | Choice between right-angled (axis-aligned) or regular (symmetric) simplex based on prior knowledge of factor effects |

| Factor Scaling Protocol | Normalizes factors to comparable magnitude | Ensures all input values are order 1-10 to prevent numerical dominance of certain factors |

| Feasibility Tolerance | Defines acceptable constraint violation in solutions | Typically set to 10⁻⁶ in floating-point implementations to accommodate numerical precision limits [8] |

| Optimality Tolerance | Determines convergence threshold | Defines when improvements become practically insignificant |

| Perturbation Mechanism | Enhances robustness against numerical issues | Small random additions to RHS or cost coefficients (e.g., uniform in [0, 10⁻⁶]) to prevent degeneracy [8] |

| Function Evaluation Protocol | Measures system response at simplex vertices | For experimental systems, requires careful experimental design and replication strategy |

Comparative Analysis and Research Implications

The evolutionary transition from the Spendley-Hext-Himsworth method to the Nelder-Mead algorithm represents a paradigm shift in optimization strategy, moving from a rigid, predetermined search pattern to an adaptive, responsive approach. This transition has profound implications for pharmaceutical researchers engaged in experimental optimization.

The adaptive capability of the Nelder-Mead method enables more efficient navigation of complex response surfaces commonly encountered in drug development, such as those with elongated ridges, discontinuous regions, or multiple local optima. The method's ability to elongate along favorable directions and contract in the vicinity of optima makes it particularly valuable for resource-intensive experimental optimization where each function evaluation represents significant time and material investment [6].

For the pharmaceutical researcher, practical implementation benefits from incorporating several strategies employed by modern optimization software: problem scaling to normalize factor magnitudes, judicious selection of termination tolerances to balance precision with computational expense, and strategic perturbation to enhance algorithmic robustness [8]. These practical refinements, coupled with the core Nelder-Mead algorithm, create a powerful optimization framework for addressing the multivariate challenges inherent in pharmaceutical development.

The historical progression of simplex methods continues to inform contemporary research in optimization algorithms, demonstrating how fundamental geometric intuition coupled with adaptive mechanisms can yield powerful practical tools for scientific exploration and pharmaceutical development.

This guide details the core operational components—vertices, reflection, expansion, and contraction—of the sequential simplex method, a fundamental algorithm for non-linear optimization. It is crucial to distinguish this method from the similarly named but conceptually different simplex algorithm used in linear programming. The linear programming simplex algorithm, developed by George Dantzig, operates by moving along the edges of a polyhedral feasible region defined by linear constraints to find an optimal solution [1]. In contrast, the sequential simplex method, attributed to Spendley, Hext, Himsworth, and later refined by Nelder and Mead, is a direct search method designed for optimizing non-linear functions where derivatives are unavailable or unreliable [9]. This paper frames the sequential simplex method within broader research on robust, derivative-free optimization principles, highlighting its particular relevance for experimental optimization in scientific fields such as drug development.

Table: Key Differences Between the Two Simplex Methods

| Feature | Sequential Simplex Method (Nelder-Mead) | Simplex Algorithm (Linear Programming) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Use Case | Non-linear optimization without derivatives [9] | Linear Programming problems [1] |

| Underlying Principle | Movement of a geometric simplex across the objective function landscape [9] | Movement between vertices of a feasible region polytope [1] |

| Typical Application | Experimental parameters, reaction yields, computational model tuning | Resource allocation, transportation, scheduling [1] |

Foundational Concepts of the Sequential Simplex Method

The sequential simplex method is applied to the minimization problem formulated as min f(x), where x is a vector of n variables [9]. The algorithm's core structure is a simplex, a geometric object formed by n+1 points (vertices) in n-dimensional space. In two dimensions, a simplex is a triangle; in three dimensions, it is a tetrahedron [9]. This collection of vertices is the algorithm's fundamental toolkit for exploring the parameter space.

Each vertex of the simplex represents a specific set of input parameters, and the algorithm evaluates the objective function f(x) at each vertex. The vertices are then ranked from best to worst based on their function values. For a minimization problem, the ranking is as follows:

x_best: The vertex with the lowest function value (f(x_best)).x_good: The vertex with the second-lowest function value (in a simplex with more than two vertices).x_worst: The vertex with the highest function value (f(x_worst)). This ranking drives the iterative process of transforming the simplex to move away from poor regions and toward the optimum.

Core Operations: Workflow and Logic

The sequential simplex method progresses by iteratively replacing the worst vertex with a new, better point. The choice of which new point to use is determined by a series of geometric operations: reflection, expansion, and contraction. The logical flow between these operations ensures the simplex adapts to the local landscape of the objective function.

Diagram 1: Logical workflow of the sequential simplex method, showing the conditions for reflection, expansion, contraction, and shrinkage.

Reflection Operation

Reflection is the primary and most frequently used operation. It moves the worst vertex directly away from the high-value region of the objective function.

- Objective: To generate a new point

x_rby reflecting the worst vertexx_worstthrough the centroidx_centroidof the remainingnvertices (all vertices exceptx_worst). - Mathematical Formulation:

x_r = x_centroid + α * (x_centroid - x_worst)- Here,

α(alpha) is the reflection coefficient, a positive constant typically set to1[9]. - The centroid is calculated as

x_centroid = (1/n) * Σ x_ifor alli ≠ worst.

- Here,

- Protocol and Acceptance: The objective function

f(x_r)is evaluated. Iff(x_r)is better thanx_goodbut worse thanx_best(i.e.,f(x_best) <= f(x_r) < f(x_good)), the reflection is considered successful.x_worstis replaced byx_r, forming a new simplex for the next iteration.

Expansion Operation

Expansion is triggered when a reflection indicates a strong potential for improvement along a specific direction, suggesting a steep descent.

- Objective: To extend the search further in the promising direction identified by a successful reflection.

- Mathematical Formulation:

x_e = x_centroid + γ * (x_r - x_centroid)- Here,

γ(gamma) is the expansion coefficient, which is greater than 1 and typically2[9].

- Here,

- Protocol and Acceptance: Expansion is attempted only if the reflected point

x_ris better than the current best vertex (f(x_r) < f(x_best)). The function valuef(x_e)is then computed. If the expanded pointx_eyields a better value thanx_r(f(x_e) < f(x_r)), thenx_worstis replaced withx_e. If not, the algorithm falls back to the still-successfulx_r.

Contraction Operation

Contraction is employed when reflection produces a point that is no better than the second-worst vertex, indicating that the simplex may be too large and is overshooting the minimum.

- Objective: To generate a new point closer to the centroid, effectively shrinking the simplex in the direction of the (presumed) optimum.

- Mathematical Formulation: The operation depends on the quality of the reflected point:

- Outside Contraction: If the reflected point

x_ris better thanx_worstbut worse thanx_good(f(x_good) <= f(x_r) < f(x_worst)), an outside contraction is performed:x_c = x_centroid + β * (x_r - x_centroid). - Inside Contraction: If the reflected point

x_ris worse than or equal tox_worst(f(x_r) >= f(x_worst)), an inside contraction is performed:x_c = x_centroid - β * (x_centroid - x_worst). - In both cases,

β(beta) is the contraction coefficient, typically0.5[9].

- Outside Contraction: If the reflected point

- Protocol and Acceptance: After calculating

x_c, the function valuef(x_c)is evaluated. Ifx_cis better thanx_worst(f(x_c) < f(x_worst)), the contraction is deemed successful, andx_worstis replaced withx_c. If the contraction fails (i.e.,x_cis not better), the algorithm proceeds to a shrinkage operation.

Shrinkage Operation

Shrinkage is a global rescue operation used when a contraction step fails to produce a better point, suggesting the current simplex is ineffective.

- Objective: To uniformly reduce the size of the simplex around the best-known vertex

x_best. - Mathematical Formulation: For every vertex

x_iin the simplex (exceptx_best), a new vertex is generated:x_i_new = x_best + σ * (x_i - x_best).- Here,

σ(sigma) is the shrinkage coefficient, typically0.5[9].

- Here,

- Protocol: The objective function is evaluated at all

nnew shrunken vertices. This operation resets the simplex, preserving the direction of the best vertex but on a smaller scale, allowing for a more localized search in the next iteration.

Table: Summary of Core Simplex Operations and Parameters

| Operation | Mathematical Formula | Typical Coefficient Value | Condition for Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reflection | x_r = x_centroid + α*(x_centroid - x_worst) |

α = 1.0 | Standard move to replace worst point. |

| Expansion | x_e = x_centroid + γ*(x_r - x_centroid) |

γ = 2.0 | f(x_r) < f(x_best) |

| Contraction | x_c = x_centroid + β*(x_r - x_centroid) (Outside) |

β = 0.5 | f(x_good) <= f(x_r) < f(x_worst) (Outside) |

x_c = x_centroid - β*(x_centroid - x_worst) (Inside) |

f(x_r) >= f(x_worst) (Inside) |

||

| Shrinkage | x_i_new = x_best + σ*(x_i - x_best) for all i ≠ best |

σ = 0.5 | Contraction has failed. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Experimental Implementation

Implementing the sequential simplex method in an experimental context, such as optimizing a drug formulation or a chemical reaction, requires careful planning and specific tools. The following table outlines the essential "research reagent solutions" for a successful optimization campaign.

Table: Essential Reagents for Sequential Simplex Experimentation

| Item / Concept | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Controllable Input Variables (e.g., pH, Temperature, Concentration) | These parameters form the dimensions of the optimization problem. Each vertex of the simplex is a unique combination of these variables. |

| Objective Function Response (e.g., Yield, Purity, Potency) | The measurable output that the algorithm seeks to optimize (maximize or minimize). It must be quantifiable and sensitive to changes in the input variables. |

| Reflection, Expansion, Contraction Coefficients (α, γ, β) | Numerical parameters that control the behavior and convergence of the algorithm. Using standard values (1, 2, 0.5) is a common starting point. |

| Convergence Criterion (e.g., Δf < ε, Max Iterations) | A predefined stopping rule to halt the optimization, such as a minimal improvement in the objective function or a maximum number of experimental runs. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol

- Initialization: Define the

ninput variables to be optimized and the objective functionf(x)to be measured. Construct the initial regular simplex inndimensions. For example, if starting from a baseline pointP_0, the othernvertices can be defined asP_0 + d * e_i, wheredis a step size ande_iis the unit vector for thei-th dimension [9]. - Iteration Loop:

a. Evaluation and Ranking: Run the experiment for each vertex of the current simplex to obtain the objective function values. Rank the vertices from best (

x_best) to worst (x_worst). b. Calculate Centroid: Compute the centroidx_centroidof all vertices excludingx_worst. c. Apply Logic Flow: Follow the decision logic outlined in Diagram 1. - Perform Reflection to getx_rand evaluatef(x_r). - Iff(x_r) < f(x_best), perform Expansion. - Iff(x_r) >= f(x_good), perform Contraction. - If contraction fails, perform Shrinkage. d. Simplex Update: Replace the appropriate vertex to form the new simplex for the next iteration. - Termination: The process concludes when a convergence criterion is satisfied, such as the difference in objective function values between iterations falling below a tolerance level, or the simplex size becoming sufficiently small. The best vertex

x_bestis reported as the estimated optimum.

The sequential simplex method provides a powerful, intuitive framework for tackling complex optimization problems where gradient information is unavailable. Its core components—the evolving set of vertices and the reflection, expansion, and contraction operations—work in concert to navigate the objective function's landscape efficiently. For researchers in drug development and other applied sciences, mastery of this method offers a structured, empirical path to optimizing processes and formulations, accelerating discovery and improving outcomes. Its robustness and simplicity ensure its continued relevance as a cornerstone of empirical optimization strategies.

Formulating an optimization problem is a critical first step in the application of mathematical programming, serving as the foundation upon which solution algorithms, including the sequential simplex method, are built. Within the context of a broader thesis on sequential simplex method basic principles research, proper problem formulation emerges as a prerequisite for effective algorithm application. The formulation process translates a real-world problem into a structured mathematical framework comprising an objective function, design variables, and constraints [10]. This translation is particularly crucial in scientific and industrial domains such as drug development, where optimal outcomes depend on precisely modeled relationships. A well-formulated problem not only enables the identification of optimal solutions but also ensures that the sequential simplex method and related algorithms operate on a model that faithfully represents the underlying system dynamics, thereby yielding physically meaningful and implementable results.

Core Components of an Optimization Problem

Every optimization problem, regardless of its domain, is built upon three fundamental components. These elements work in concert to create a complete mathematical representation of the problem to be solved.

- Objective Function: This is the mathematical function to be minimized or maximized. It quantifies the performance or cost of a system, providing a scalar measure that the optimizer seeks to improve [10]. In a drug development context, this could represent the minimization of production costs or the maximization of product purity.

- Design Variables: These are the choices that directly influence the value of the objective function [10]. Design variables represent the parameters under the control of the researcher or engineer, such as temperature, concentration, or material selection in a pharmaceutical process.

- Constraints: These are the limits on design variables and other quantities of interest that define feasible solutions [10]. Constraints represent physical, economic, or safety limitations, such as maximum allowable pressure in a reactor or regulatory limits on impurity concentrations.

Table 1: Core Components of an Optimization Problem

| Component | Description | Example from Drug Development |

|---|---|---|

| Objective Function | Mathematical function to be minimized/maximized | Minimize production cost of an active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) |

| Design Variables | Parameters under control of the researcher | Temperature, reaction time, catalyst concentration |

| Constraints | Limits that define feasible solutions | Purity ≥ 99.5%, Total processing time ≤ 24 hours |

The mathematical form of a conventional optimization problem can be expressed as follows. For a minimization problem, we seek to find the value x that satisfies:

Minimize ( f(\mathbf{x}) ), subject to ( gi(\mathbf{x}) \leq 0, \quad i = 1, \ldots, m ), and ( hj(\mathbf{x}) = 0, \quad j = 1, \ldots, p ), where ( \mathbf{x} ) is the vector of design variables, ( f(\mathbf{x}) ) is the objective function, ( gi(\mathbf{x}) ) are inequality constraints, and ( hj(\mathbf{x}) ) are equality constraints [11]. It is important to note that any maximization problem can be converted to a minimization problem by negating the objective function, since ( \max f(\mathbf{x}) ) is equivalent to ( \min -f(\mathbf{x}) ) [11].

A Systematic Methodology for Problem Formulation

Formulating optimization problems effectively requires a structured approach to ensure all critical aspects are captured. The following methodology provides a repeatable process for translating real-world problems into mathematical optimization models.

- Identify the Optimization Goal and Constraints: Begin by clearly defining what needs to be minimized or maximized, and identify all limiting factors. In scientific contexts, this requires deep domain knowledge to distinguish between hard physical constraints and desirable performance targets [10].

- Define Variables and Units: Establish all design variables and assign appropriate units of measurement. As highlighted in optimization guidelines, it is crucial to "decide what the variables are and in what units their values are being measured in" [12] to maintain dimensional consistency throughout the model.

- Develop the Objective Function Formulation: Construct a mathematical function that relates the design variables to the optimization goal. This function must be sensitive to changes in the design variables to provide meaningful direction to optimization algorithms [10].

- Formulate Constraint Equations: Translate all identified limitations into mathematical inequalities or equalities using the defined variables. These constraints collectively define the feasible region within which the optimal solution must reside [12].

- Define the Problem Domain: Specify the domain for all variables, particularly noting any non-negativity requirements or other fundamental limitations. In the standard form required by the simplex method, for instance, "the decision variables, X_i, are nonnegative" [13].

Diagram 1: Optimization Formulation Workflow

The Simplex Method: From Formulation to Standard Form

The simplex method, a fundamental algorithm in linear programming, requires problems to be expressed in a specific standard form. Understanding this requirement is essential for researchers applying optimization techniques to scientific problems. The standard form for the simplex method requires that "the objective function is of maximization type," "the constraints are equations (not inequalities)," "the decision variables, X_i, are nonnegative," and "the right-hand-side constant (resource) of each constraint is non-negative" [13].

To transform a general linear programming problem into standard form for the simplex method, several modification techniques may be employed:

- Converting Inequalities to Equations: Add nonnegative "slack variables" to ≤ constraints or subtract nonnegative "surplus variables" from ≥ constraints. For example, in the constraint ( X1 + X2 \leq 10 ), adding a slack variable ( X3 \geq 0 ) yields the equation ( X1 + X2 + X3 = 10 ) [13].

- Handling Free Variables: Variables that can take on negative values must be expressed as the difference between two nonnegative variables.

- Right-Hand-Side Non-negativity: Any constraint with a negative right-hand-side constant must be multiplied by -1, reversing the inequality direction.

Table 2: Transformation to Simplex Standard Form

| Element | General Form | Standard Form for Simplex | Transformation Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Objective | Minimize ( Z ) | Maximize ( -Z ) | Negate the objective function |

| Inequality Constraints | ( A\mathbf{x} \leq \mathbf{b} ) | ( A\mathbf{x} + \mathbf{s} = \mathbf{b} ) | Add slack variables ( \mathbf{s} \geq 0 ) |

| Variable Bounds | ( x_i ) unrestricted | ( x_i \geq 0 ) | Replace with ( xi = xi^+ - x_i^- ) |

| Negative RHS | ( \cdots \leq -k ) | ( \cdots \geq k ) | Multiply constraint by -1 |

Diagram 2: Transformation to Simplex Standard Form

Experimental Protocols and Case Studies in Formulation

Profit Maximization in Product Sales

Consider a scenario where a company wants to determine the optimal price point to maximize profit, given market research on price-demand relationships. The experimental protocol for this formulation involves:

Experimental Protocol:

- Data Collection: Gather market data on baseline sales (5000 items at $1.50) and demand sensitivity (additional 1000 items per each $0.10 price decrease below $1.50).

- Cost Structure Identification: Determine fixed costs ($2000) and variable costs per item ($0.50).

- Model Formulation:

- Let ( x ) represent the price per item.

- The number of items sold: ( n = 5000 + \frac{1000(1.5 - x)}{0.10} ).

- Profit function: ( P(x) = n \cdot x - 2000 - 0.50n ).

- Simplified: ( P(x) = -10000x^2 + 25000x - 12000 ).

- Optimization: Find the maximum of ( P(x) ) for ( 0 \leq x \leq 1.5 ) using calculus or appropriate algorithms.

Results: The critical point occurs at ( x = 1.25 ) with profit ( P(1.25) = 3625 ), indicating the optimal price is $1.25, yielding a maximum profit of $3625 [12].

Average Cost Minimization in Manufacturing

In pharmaceutical manufacturing, minimizing average production cost per unit is essential for efficiency. The following protocol outlines this formulation:

Experimental Protocol:

- Cost Modeling: Establish a daily average cost function based on production data: ( \overline{C}(q) = 0.0001q^2 - 0.08q + 65 + \frac{5000}{q} ), where ( q > 0 ) represents units produced per day.

- Derivative Analysis: Compute ( \overline{C}'(q) = 0.0002q - 0.08 - \frac{5000}{q^2} ) to find critical points.

- Optimal Production Validation: Solve ( \overline{C}'(q) = 0 ) and verify using the second derivative test: ( \overline{C}''(q) = 0.0002 + \frac{10000}{q^3} > 0 ) for all ( q > 0 ).

Results: The minimum average cost occurs at ( q = 500 ) units, with a minimum cost of $60 per unit [12]. The positive second derivative confirms this is indeed a minimum.

Manufacturing Capacity Optimization

For production facilities, identifying periods of peak operational efficiency is valuable for capacity planning. The experimental approach includes:

Experimental Protocol:

- Data Series Collection: Collect operating rate data over a 365-day period: ( f(t) = 100 + \frac{800t}{t^2 + 90000} ), where ( t ) represents the day.

- Derivative Computation: Calculate ( f'(t) = \frac{-800(t^2 - 90000)}{(t^2 + 90000)^2} ).

- Critical Point Identification: Solve ( f'(t) = 0 ) within the domain ( [0, 365] ).

- Endpoint Comparison: Evaluate ( f(t) ) at critical points and endpoints.

Results: The critical point at ( t = 300 ) days yields an operating rate of ( f(300) = 101.33\% ), compared to ( f(0) = 100\% ) and ( f(365) = 101.308\% ), confirming day 300 as the optimal operating rate [12].

Table 3: Summary of Optimization Case Study Results

| Case Study | Objective Function | Optimal Solution | Optimal Value | Constraints |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Profit Maximization | ( P(x) = -10000x^2 + 25000x - 12000 ) | ( x = 1.25 ) | ( P = 3625 ) | ( 0 \leq x \leq 1.5 ) |

| Cost Minimization | ( \overline{C}(q) = 0.0001q^2 - 0.08q + 65 + \frac{5000}{q} ) | ( q = 500 ) | ( \overline{C} = 60 ) | ( q > 0 ) |

| Capacity Optimization | ( f(t) = 100 + \frac{800t}{t^2 + 90000} ) | ( t = 300 ) | ( f(t) = 101.33 ) | ( 0 \leq t \leq 365 ) |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Implementing optimization methodologies in research environments requires both computational and experimental tools. The following table outlines essential components for establishing optimization capabilities in scientific settings.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Tool/Reagent | Function/Purpose | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Linear Programming Solver | Algorithm implementation for solving linear optimization problems | Executing the simplex method on formulated problems |

| Calculus-Based Analysis Tools | Finding critical points and extrema of continuous functions | Solving unconstrained optimization problems analytically |

| Sensitivity Analysis Framework | Determining solution robustness to parameter changes | Post-optimality analysis in formulated models |

| Slack/Surplus Variables | Mathematical transformation of inequality constraints | Converting problems to standard form for simplex method |

| Computational Modeling Software | Numerical implementation and solution of optimization models | Prototyping and solving complex formulation scenarios |

The formulation of optimization problems represents a critical bridge between real-world challenges and mathematical solution techniques. For researchers applying the sequential simplex method to scientific problems, proper formulation—with clearly defined objectives, design variables, and constraints—ensures that algorithmic solutions yield meaningful, implementable results. The case studies and methodologies presented demonstrate that effective formulation requires both domain expertise and mathematical rigor. As optimization continues to play an increasingly important role in scientific domains including drug development, mastering the principles of problem formulation remains fundamental to research success. Future work in this area will explore multi-objective optimization formulations that address competing goals simultaneously, extending the single-objective framework discussed herein.

The efficiency of the sequential simplex method in optimization, particularly within pharmaceutical development, is critically dependent on the initial simplex configuration. This technical guide explores foundational and advanced strategies for establishing this starting point, framing them within broader research on simplex method principles. Effective initialization dictates the algorithm's convergence rate and ability to locate global optima in complex response surfaces, such as those encountered in drug formulation. This paper provides a comparative analysis of initialization protocols, detailed experimental methodologies, and visualization of the underlying logical workflows to equip researchers with the tools for enhanced experimental efficiency.

In mathematical optimization, the simplex method refers to two distinct concepts: the linear programming simplex algorithm developed by George Dantzig and the geometric simplex-based search method for experimental optimization. This guide focuses on the latter, a powerful heuristic for navigating multi-factor response surfaces. A simplex is a geometric figure defined by (k + 1) vertices in a (k)-dimensional factor space; for two factors, it is a triangle, while for three, it is a tetrahedron [14]. The sequential simplex method operates by moving this shape through the experimental domain based on rules that reject the worst-performing vertex and replace it with a new one.

The initialization strategy—the process of selecting the initial (k+1) experiments—is paramount. The starting simplex's size, orientation, and location in the factor space set the trajectory for all subsequent exploration. An ill-chosen simplex can lead to slow convergence, oscillation, or convergence to a local, rather than global, optimum. Within pharmaceutical product development, where factors like disintegrant concentration and binder concentration are critical, a systematic and efficient initialization protocol preserves valuable resources and accelerates the development timeline [14]. This guide details the core principles and modern advancements in these crucial first steps.

Core Principles and Quantitative Comparison of Initialization Methods

The choice of initialization method is a fundamental first step in designing a simplex optimization. The following table summarizes the key characteristics of the primary strategies.

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Simplex Initialization Methods

| Method Name | Number of Initial Experiments | Factor Space Coverage | Flexibility | Best-Suited Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basic Simplex | (k + 1) | Fixed | Low | Preliminary screening in well-behaved systems |

| Modified Simplex (Nelder-Mead) | (k + 1) | Variable (Adapts via reflection, expansion, contraction) | High | Systems with unknown or complex response landscapes |

| Linear Programming (LP) Phase I | Varies (uses slack/artificial variables) | Focused on constraint feasibility | N/A | Establishing a feasible starting point for constrained LP problems [15] |

The Basic Simplex Method, introduced by Spendley et al., uses a regular simplex (e.g., an equilateral triangle for two factors) that maintains a fixed size and orientation throughout the optimization [14]. Its primary strength is simplicity, but this rigidity can limit its efficiency. In contrast, the Modified Simplex Method (Nelder-Mead) starts with the same number of initial experiments but allows the simplex to change its size and shape through operations like Reflection (R), Expansion (E), and Contraction (Cr, Cw). This adaptability allows it to navigate ridges and curved valleys in the response surface more effectively, making it the preferred choice for most complex, real-world applications like drug formulation [14].

For linear programming problems, initialization is addressed through a Phase I procedure. This involves introducing slack variables to convert inequalities to equations and, if a starting point is not obvious, artificial variables to find an initial feasible solution. The objective in Phase I is to minimize the sum of these artificial variables, driving them to zero to obtain a feasible basis for the original problem [15].

Detailed Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Constructing a Basic Initial Simplex

The following workflow details the steps for establishing a starting simplex for a two-factor (e.g., disintegrant and binder concentration) optimization.

- Define Factor Ranges: Establish the minimum and maximum allowable values for each factor under investigation. This defines the bounded experimental region.

- Select a Starting Vertex (B): Choose a baseline formulation based on prior knowledge or a best guess. This point, often labeled B (Best), becomes one vertex of the initial simplex.

- Calculate Remaining Vertices: The other vertices are generated by systematically varying the factors from the starting point. For a basic, fixed-size simplex, the new vertices (N, W) are calculated by applying a predetermined step size to each factor. The resulting simplex ensures non-degeneracy and a balanced initial exploration.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for a Typical Drug Formulation Simplex Optimization

| Research Reagent / Material | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API) | The primary drug compound whose delivery is being optimized. |

| Disintegrant (e.g., Croscarmellose Sodium) | A reagent that promotes the breakdown of a tablet in the gastrointestinal tract. |

| Binder (e.g., Polyvinylpyrrolidone) | A reagent that provides cohesion, ensuring the powder mixture can be compressed into a tablet. |

| Lubricant (e.g., Magnesium Stearate) | Prevents adhesion of the formulation to the manufacturing equipment. |

| Dissolution Testing Apparatus | The experimental setup used to measure the drug release profile, a key response variable. |

Protocol for the Modified Simplex (Nelder-Mead) Operations

The modified method's power lies in its operational rules, which are applied after the initial simplex is constructed and its responses are measured.

- Rank Vertices: After running the experiments for all (k+1) vertices, rank them from best (B) to worst (W) based on the objective function (e.g., dissolution rate).

- Calculate and Test Reflection (R): Generate the reflected vertex R by moving away from the worst vertex W through the centroid of the remaining vertices. The coordinate for R is calculated as (R = P + (P - W)), where P is the centroid. Test R experimentally.

- If B > R > N: R is accepted, and a new simplex is formed with B, N, and R.

- If R > B: Proceed to Expansion.

- Expansion (E): If R is better than B, the direction is promising, and an expansion is warranted. Calculate E by extending further beyond R, (E = P + \gamma (P - W)), where (\gamma > 1). Test E.

- If E > B: E is accepted, forming a new simplex with B, N, and E.

- If E < B: R is accepted instead.

- Contraction: If R is worse than N, the simplex is likely too large and must contract.

- Exterior Contraction (Cr): If R is better than W (i.e., N > R > W), calculate Cr as (Cr = P + \beta (P - W)), where (0 < \beta < 1). Test Cr. If Cr > W, accept it.

- Interior Contraction (Cw): If R is worse than W (i.e., W > R), perform a stronger interior contraction, (Cw = P - \beta (P - W)). Test Cw. If Cw > W, accept it.

- Termination Check: If no improvement is found through contraction, the algorithm is likely near an optimum. The process terminates when the differences in response between vertices fall below a pre-specified threshold or a maximum number of iterations is reached [14].

Visualization of Simplex Workflows

The following diagrams, generated with Graphviz, illustrate the logical relationships and decision pathways of the core simplex processes.

Workflow of the Modified Simplex Operations

Diagram 1: Modified Simplex Operational Workflow

Logical Pathway for Initial Feasible Solution in LP

Diagram 2: Initialization Pathway for Linear Programming (Phase I)

Advanced Topics and Streamlined Methods

Recent research has focused on overcoming the limitations of traditional two-phase LP approaches. The streamlined artificial variable-free simplex method represents a significant advancement. This method can start from an arbitrary initial basis, whether feasible or infeasible, without explicitly adding artificial variables or artificial constraints [16].

The method operates by implicitly handling infeasibilities. As the algorithm iterates, it follows the same pivoting sequence as the traditional Phase I, but infeasible variables are replaced by their corresponding "invisible" slack variables upon leaving the basis. This approach offers several key advantages:

- Space Efficiency: The simplex tableau is smaller as it lacks columns for artificial variables.

- Pedagogical Clarity: It allows students and researchers to learn feasibility achievement (Phase I) independently from optimality achievement (Phase II).

- Computational Benefit: It eliminates the need for the big-M method or other reformulations, saving iterations and reducing complexity, especially for large-scale problems [16].

A dual version of this method also exists, providing an equally efficient and artificial-constraint-free method for achieving dual feasibility, further enhancing the toolkit available to researchers and practitioners solving complex linear programs [16].

Implementing the Simplex Method: A Step-by-Step Guide and Real-World Applications in Drug Development

The simplex algorithm, developed by George Dantzig in 1947, stands as a cornerstone of linear programming optimization [1] [17]. This algorithm addresses the fundamental challenge of allocating limited resources to maximize benefits or minimize costs, a problem pervasive in operational research, logistics, and pharmaceutical development [17]. Within the context of sequential simplex method basic principles research, understanding its iterative workflow is crucial for both theoretical comprehension and practical implementation. The algorithm's elegance lies in its systematic approach to navigating the vertices of a multidimensional polytope, consistently moving toward an improved objective value with each operation [1] [4]. This technical guide provides a comprehensive examination of the simplex method's procedural workflow, with detailed protocols and visualizations to aid researchers and scientists in its application.

Mathematical Foundation and Standard Form

Core Formulation

The simplex algorithm operates on linear programs expressed in canonical form, which serves as the starting point for the optimization process [1]. This form is characterized by:

- Objective Function: A linear function to be maximized or minimized: maximize cᵀx [1]

- Constraints: A system of linear inequalities: Ax ≤ b [1]

- Non-negativity: All decision variables must be non-negative: x ≥ 0 [1]

In this formulation, c = (c₁, ..., cₙ) represents the coefficients of the objective function, x = (x₁, ..., xₙ) is the vector of decision variables, A is the constraint coefficient matrix, and b = (b₁, ..., bₚ) is the right-hand-side vector of constraints [1].

Conversion to Standard Form

To enable the simplex method's algebraic operations, problems must first be converted to standard form through a series of transformations [1]:

Slack Variables: For each inequality constraint of the form aᵢ₁x₁ + aᵢ₂x₂ + ... + aᵢₙxₙ ≤ bᵢ, introduce a non-negative slack variable sᵢ to convert the inequality to an equation: aᵢ₁x₁ + aᵢ₂x₂ + ... + aᵢₙxₙ + sᵢ = bᵢ [1] [17]. These variables represent unused resources and form an initial basic feasible solution [4].

Surplus Variables: For constraints with ≥ inequalities, subtract a non-negative surplus variable to achieve equality [1].

Unrestricted Variables: For variables without non-negativity constraints, replace them with the difference of two non-negative variables [1].

After transformation, the standard form becomes [1]:

- maximize cᵀx

- subject to Ax = b

- with x ≥ 0

The Core Iterative Workflow

The simplex method progresses through a systematic iterative process, moving from one basic feasible solution to an adjacent one with an improved objective value until optimality is reached or unboundedness is detected [18]. The workflow diagram below illustrates this process.

Initialization and Tableau Construction

The algorithm begins by constructing an initial simplex tableau, which serves as the computational framework for all subsequent operations [4] [18]. The tableau organizes all critical information into a matrix format:

The initial dictionary matrix takes the form [4]:

- D =

[0 cᵀ 0; 0 -Ā b] - Where Ā = [A Iₘ] (the original constraint matrix augmented with identity matrix for slack variables)

- And c̄ = [c 0] (original cost vector extended with zeros for slack variables)

For a problem with n original variables and m constraints, the initial tableau has m+1 rows and n+m+1 columns [4].

Optimality Checking

At the beginning of each iteration, the algorithm checks whether the current solution is optimal by examining the objective row coefficients (excluding the first column) [18]. The termination condition is:

- If all coefficients in the objective row are non-negative, the current solution is optimal, and the algorithm terminates [18].

If any objective coefficient is negative, selecting the corresponding variable to increase may improve the objective value, and the algorithm proceeds to the next step [19].

Entering Variable Selection

When the solution is not optimal, the algorithm selects a non-basic variable to enter the basis (become non-zero). The standard selection rule is:

- Identify the most negative coefficient in the objective row [4] [18].

- The variable corresponding to this column becomes the entering variable [18].

This selection strategy, while not the most computationally efficient, ensures strict improvement in the objective function at each iteration [19]. Advanced implementations may use more sophisticated criteria, but the fundamental principle remains the same.

Ratio Test and Leaving Variable Selection

Once the entering variable (pivot column) is determined, the algorithm identifies which basic variable will leave the basis using the minimum ratio test [4] [18]:

- For each constraint row i, compute the ratio: rᵢ = bᵢ / aᵢₑ where aᵢₑ is the coefficient in the pivot column for row i [4].

- Select the constraint row with the smallest non-negative ratio [18].

- The basic variable corresponding to this row becomes the leaving variable [18].

This minimum ratio test ensures feasibility is maintained by preventing any variable from becoming negative [18]. If all entries in the pivot column are non-positive, the problem is unbounded, and the algorithm terminates [4].

Pivot Operation

The pivot operation transforms the tableau to reflect the new basis [1] [4]. This Gaussian elimination process consists of:

- Pivot Row Normalization: Divide the pivot row by the pivot element to make the pivot element equal to 1 [18].

- Row Operations: For all other rows (including the objective row), subtract an appropriate multiple of the new pivot row to make all other entries in the pivot column equal to zero [18].

The resulting tableau represents the new basic feasible solution with an improved objective value [1]. The algorithm then returns to the optimality check step, continuing this iterative process until termination.

Implementation Protocols and Experimental Framework

Tableau Transformation Diagram

The pivot operation's effect on the tableau structure is visualized below.

Computational Materials and Research Reagents

Successful implementation of the simplex method requires both theoretical understanding and appropriate computational tools. The following table details the essential components for experimental application.

| Component | Specification | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Tableau Structure [4] | Matrix of size (m+1) × (n+m+1) | Primary data structure organizing constraints, objective, and solution values throughout iterations. |

| Slack Variables [1] [17] | Identity matrix appended to constraints | Transform inequalities to equalities; provide initial basic feasible solution. |

| Pivot Selection Rules [4] [18] | Most negative coefficient for entering variable; minimum ratio test for leaving variable | Determine transition between adjacent vertices while maintaining feasibility and improving objective. |

| Tolerances [8] | Feasibility tolerance (~10⁻⁶); optimality tolerance (~10⁻⁶) | Handle floating-point arithmetic limitations; determine satisfactory satisfaction of constraints and optimality. |

| Numerical Scaling [8] | Normalize input values to similar magnitudes (order of 1) | Improve numerical stability and conditioning; prevent computational errors from disparate variable scales. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol

Researchers implementing the simplex method should follow this detailed experimental protocol:

Problem Formulation Protocol:

Standard Form Conversion Protocol:

Initialization Protocol:

Iteration Execution Protocol:

- Check optimality by scanning objective row for negative coefficients [18].

- Select entering variable using the most negative coefficient rule [4] [18].

- Perform minimum ratio test to identify leaving variable [4] [18].

- Execute pivot operation using Gaussian elimination [1] [18].

- Monitor objective value improvement for convergence validation [1].

Termination Protocol:

Industrial Production Case Study

To illustrate the simplex method's practical application, consider a factory manufacturing three products (P1, P2, P3) with the following characteristics [17]:

| Product | Raw Material (kg/unit) | Machine Time (h/unit) | Profit ($/unit) |

|---|---|---|---|

| P1 (x₁) | 6 | 3 | 8.00 |

| P2 (x₂) | 4 | 1.5 | 3.50 |

| P3 (x₃) | 4 | 2 | 6.00 |

Weekly constraints [17]:

- Raw material: 6x₁ + 4x₂ + 4x₃ ≤ 10,000 kg

- Machine time: 3x₁ + 1.5x₂ + 2x₃ ≤ 6,000 hours

- Storage capacity: x₁ + x₂ + x₃ ≤ 3,500 units

Objective: Maximize profit: z = 8x₁ + 3.5x₂ + 6x₃ [17]

The iterative progression of the simplex method for this problem demonstrates the algorithm's quantitative behavior:

| Iteration | Entering Variable | Leaving Variable | Pivot Element | Objective Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | x₁ | e₂ | 6 | 0 |

| 1 | x₃ | e₁ | 0 | 13,333.33 |

| 2 | x₂ | e₃ | 0.67 | 15,166.67 |

| 3 | - | - | - | 16,050.00 |

Advanced Implementation Considerations

Degeneracy and Cycling Prevention

In practical implementations, the simplex method must address potential computational challenges:

- Bland's Rule: To prevent cycling at degenerate vertices, employ Bland's rule, which selects the variable with the smallest index when facing multiple choices for entering or leaving variables [4].

- Perturbation Methods: Modern solvers add small random perturbations to constraint right-hand sides (e.g., bᵢ = bᵢ + ε where ε ∈ [0, 10⁻⁶]) to avoid structural degeneracy [8].

Numerical Stability Enhancements

Industrial-scale simplex implementations incorporate several techniques to ensure robustness:

- Scaling Procedures: Normalize all non-zero input numbers to be of order 1, with feasible solutions having non-zero entries of order 1 [8].

- Tolerance Parameters: Implement feasibility tolerance (allow Ax ≤ b + 10⁻⁶) and optimality tolerance to accommodate floating-point arithmetic limitations [8].

- Matrix Inversion Updates: Use efficient basis update methods rather than complete recomputation to enhance computational efficiency [8].

The simplex method's iterative workflow represents a powerful algorithmic framework for linear optimization problems. Its systematic approach of moving between adjacent vertices, guided by pivot operations and optimality checks, provides both theoretical guarantees and practical effectiveness. For researchers in pharmaceutical development and other optimization-intensive fields, mastering this algorithmic workflow enables solution of complex resource allocation problems that underlie critical decisions in drug formulation, clinical trial design, and manufacturing optimization. The detailed protocols, visualization tools, and implementation guidelines presented in this whitepaper provide a comprehensive reference for applying these techniques within contemporary research environments, establishing a foundation for further innovation in sequential simplex method applications.

In the realm of experimental optimization, particularly within pharmaceutical and process development, researchers constantly face the challenge of efficiently navigating complex experimental spaces to identify ideal operating conditions or "sweet spots." Sequential simplex methods represent a class of optimization algorithms specifically designed for this purpose, enabling systematic experimentation with multiple variables. These methods operate on the fundamental principle of moving through a geometric figure (a simplex) positioned within the experimental response space, iteratively guiding experiments toward optimal conditions by reflecting away from poor performance points. Within this family of approaches, a critical distinction exists between the Basic Simplex Method and various Modified Simplex Algorithms. The Basic Simplex, often called the standard sequential simplex, follows a fixed set of rules for generating new experimental vertices. In contrast, Modified Simplex approaches introduce adaptive rules for expansion, contraction, and boundary handling, granting greater flexibility and efficiency for real-world experimental challenges. This guide provides an in-depth technical comparison of these approaches, framed within the context of broader thesis research on simplex principles, to empower scientists in selecting the most appropriate strategy for their specific experimental objectives.

Theoretical Foundations: Basic Simplex Principles

The Simplex Method, originally developed by George Dantzig in 1947 for linear programming, provides a systematic procedure for testing vertices as possible solutions to optimization problems [20]. In the context of experimental optimization, the algorithm operates on a fundamental geometric principle: for a problem with k variables, the simplex is a geometric figure defined by k+1 vertices in the k-dimensional factor space [20]. Each vertex represents a specific combination of experimental conditions, and the corresponding response or outcome is measured.

The algorithm's procedure can be summarized as follows: It begins by evaluating the initial simplex. The worst-performing vertex is identified and reflected through the centroid of the remaining vertices to generate a new candidate point. This process iteratively moves the simplex across the response surface toward more promising regions. The strength of this approach lies in its systematic elimination of suboptimal regions and its progressive focus on areas likely to contain the optimum. The Basic Simplex Method is particularly valued for its conceptual simplicity, computational efficiency, and guaranteed convergence to a local optimum under appropriate conditions [1] [20].

Table: Core Terminology of Sequential Simplex Methods

| Term | Definition | Experimental Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Vertex | A point defined by a set of coordinates in the factor space | A specific combination of experimental factor levels (e.g., pH, temperature, concentration) |

| Simplex | A geometric figure with k+1 vertices in k dimensions | The current set of experiments being evaluated |

| Response | The measured outcome at a vertex | The experimental result (e.g., yield, purity, activity) used to judge performance |

| Reflection | A geometric operation that generates a new vertex by moving away from the worst response | A calculated new set of conditions predicted to yield better performance |

| Centroid | The center point of all vertices excluding the worst | The average of the better-performing experimental conditions |

The Modified Simplex Framework: Adaptive Optimization for Complex Experiments

Modified Simplex algorithms, often referred to as the "Modified Simplex Method" or sophisticated variants like the Hybrid Experimental Simplex Algorithm (HESA), enhance the basic framework with adaptive rules that dramatically improve performance in practical settings [21]. These modifications address key limitations of the basic approach, particularly its fixed step size and potential inefficiency on response surfaces with ridges or curved optimal regions.

The most significant enhancement in modified approaches is the introduction of expansion and contraction operations. Unlike the basic method that only reflects the worst point, a modified algorithm can expand the simplex in a promising direction if the reflected point shows substantial improvement, effectively accelerating progress toward the optimum [21]. Conversely, if the reflected point remains poor, the simplex contracts, moving the worst point closer to the centroid of the remaining points. This contraction allows the simplex to reduce its size and navigate more carefully when it encounters complex response topography. These dynamic adjustments make the modified simplex particularly powerful for "coarsely gridded data" and for identifying the size, shape, and location of operational "sweet spots" in bioprocess development and other experimental domains [21].

Another critical modification involves handling boundary constraints. Experimental factors invariably have practical limits (e.g., pH cannot be negative, concentration has physical solubility limits). Modified algorithms incorporate sophisticated boundary management strategies that either reject moves that violate constraints or redirect the simplex along the constraint boundary, ensuring all experimental suggestions remain physically realizable.

Figure 1: Modified Simplex Algorithm Decision Workflow - This flowchart illustrates the adaptive decision points (expansion, reflection, contraction) that distinguish modified simplex approaches from the basic method.

Comparative Analysis: Basic vs. Modified Simplex Approaches

The choice between Basic and Modified Simplex methods hinges on understanding their operational characteristics and how they align with specific experimental goals. The following comparative analysis highlights key distinctions that should inform this decision.

Table: Comparative Analysis of Basic vs. Modified Simplex Characteristics

| Characteristic | Basic Simplex Method | Modified Simplex Method |

|---|---|---|

| Step Size | Fixed step size throughout the procedure | Variable step size (reflection, expansion, contraction) |

| Convergence Speed | Generally slower, more experiments required | Faster convergence, particularly on well-behaved surfaces |

| Complex Terrain Navigation | May oscillate or perform poorly on ridges or curved paths | Superior navigation through expansion/contraction |

| Boundary Handling | Limited or simplistic constraint management | Sophisticated boundary management strategies |

| Experimental Efficiency | Lower information return per experiment | Higher information return, better "sweet spot" identification [21] |

| Implementation Complexity | Simpler to implement and understand | More complex algorithm with additional decision rules |

| Optimal Solution Refinement | May not finely converge on exact optimum | Better refinement near optimum due to contraction |