Sequential Simplex Optimization: A Practical Guide for Multi-Factor Optimization in Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive guide to Sequential Simplex Optimization, a powerful multivariate chemometric tool for efficiently optimizing multiple factors in complex systems.

Sequential Simplex Optimization: A Practical Guide for Multi-Factor Optimization in Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to Sequential Simplex Optimization, a powerful multivariate chemometric tool for efficiently optimizing multiple factors in complex systems. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it covers foundational principles, from the basic and modified Nelder-Mead algorithms to advanced methodological applications in analytical chemistry and pharmaceutical processes. The scope includes practical strategies for troubleshooting common issues like premature convergence, a comparative analysis with alternative methods such as Interior Point algorithms, and validation techniques to ensure robust, reliable outcomes. By synthesizing theory and real-world case studies, this guide serves as an essential resource for accelerating development cycles and enhancing optimization efficacy in biomedical research.

Understanding Sequential Simplex: Core Principles and Geometric Foundations for Efficient Optimization

Defining Sequential Simplex Optimization and Its Role in Multivariate Analysis

Frequently Asked Questions

What is Sequential Simplex Optimization? Sequential Simplex Optimization, often referred to as the simplex method for function minimization or the Nelder-Mead method, is a direct search algorithm used for optimizing a function of multiple variables without needing to compute derivatives [1]. It is a geometric approach where the "simplex" is a geometric figure formed by a set of n+1 points in an n-dimensional space (e.g., a triangle in 2D, a tetrahedron in 3D) [1] [2]. The method works by iteratively moving this simplex through the experimental domain, reflecting and reshaping it to navigate towards the optimal region [2].

How does it differ from the Simplex Algorithm for Linear Programming? It is crucial to distinguish this method from the similarly named but distinct Simplex Algorithm developed by George Dantzig for Linear Programming problems [3] [4]. Dantzig's algorithm solves linear optimization problems with linear constraints by moving along the edges of a feasible region polytope [3] [5]. In contrast, the Sequential Simplex Method is designed for non-linear, multivariate optimization of empirical functions, commonly used in experimental response surface methodology [1] [2].

What are the advantages of using a sequential approach? The primary advantage is its efficiency in navigating complex experimental landscapes with a minimal number of experiments. Unlike comprehensive but static experimental designs (e.g., Central Composite Designs), the sequential simplex approach uses information from immediately preceding experiments to determine the next best point to evaluate, allowing it to rapidly converge towards an optimum without mapping the entire response surface first [2]. This makes it particularly useful when experiments are time-consuming or expensive.

What is a common stopping criterion for the simplex? A common stopping criterion is when the simplex begins to circulate or "circle" around a potential optimum, with only minor improvements in the response value between iterations [2]. The procedure can also be stopped once the measured response meets the desired performance specifications or when the simplex has shrunk below a pre-defined size, indicating that further refinement is unlikely.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: The Simplex is Oscillating or Circling an Point Without Converging

- Potential Cause: The simplex has become trapped on a "false" ridge in the response surface or is reacting to experimental noise.

- Solution:

- Apply a contraction step: The standard algorithm includes a contraction rule for this scenario, which reduces the size of the simplex to refine the search in the immediate vicinity [1].

- Restart the algorithm: If oscillation persists, halt the procedure and restart with a new, smaller simplex centered on the best point found so far.

- Verify experimental precision: Ensure that your experimental measurement variability (noise) is small relative to the effect sizes you are trying to optimize.

Problem: Convergence is Too Slow

- Potential Cause: The initial simplex size is too small, leading to a slow progression across the experimental domain [2].

- Solution:

- Re-start with a larger simplex: Begin a new sequence of experiments using a larger initial simplex size to cover ground more quickly.

- Use a variable-size simplex method: Implement an advanced version of the algorithm, such as the one developed by Nelder and Mead, which includes rules for expansion and contraction, allowing it to automatically adapt its size and shape to the response landscape [1] [2].

Problem: The Method Fails to Find the Known Global Optimum

- Potential Cause: The sequential simplex is a local search method and can converge to the nearest local optimum, potentially missing a better, global optimum in a different region.

- Solution:

- Run from multiple starting points: Initiate the simplex procedure from several different, widely spaced initial locations within the feasible experimental domain.

- Use in a hybrid strategy: First, use a screening design (e.g., fractional factorial) to identify the most important factors and their approximate optimal ranges. Then, use the sequential simplex for fine-tuning within a promising region [2].

Experimental Protocol: Implementing a Sequential Simplex for Method Optimization

The following protocol outlines the steps for using a sequential simplex to optimize an analytical method, such as the composition of an in-situ film electrode as described in the research [6].

1. Define the System and Response

- Identify Factors: Select the

ncontinuous variables (factors) to be optimized (e.g., mass concentrations of Bi(III), Sn(II), Sb(III), accumulation potential, accumulation time) [6]. - Define the Response: Establish a clear, quantifiable Objective Function to maximize or minimize. This could be a single metric (e.g., sensitivity, peak current) or a composite desirability function combining multiple responses (e.g., balancing low limit of detection with a wide linear concentration range) [6] [2].

2. Establish the Initial Simplex

- Choose a Starting Point (

P_0): Based on prior knowledge or preliminary experiments, select a feasible initial combination of factor levels. - Calculate Other Vertices: The other

nvertices of the initial simplex are typically generated by adding a fixed step size to each factor in turn, starting fromP_0. Fornfactors, this createsn+1initial experiments.

3. Run Experiments and Rank Results

- Execute the experiments corresponding to each vertex of the current simplex.

- Measure the response for each vertex.

- Rank the vertices from Worst (W) to Best (B) based on the measured response.

4. Iterate the Simplex The core iterative process involves four operations: Reflection, Expansion, Contraction, and Shrinkage [1]. The workflow for a single iteration is as follows:

5. Termination

- Continue the iterative process until a stopping criterion is met, such as the simplex size becoming smaller than a predefined threshold or the response improvement falling below a minimal delta.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key materials and parameters used in a referenced sequential simplex optimization study for an electrochemical sensor [6].

| Research Reagent / Parameter | Function / Role in Optimization |

|---|---|

| Bi(III) ions | Component for forming in-situ bismuth-film electrode (BiFE); influences sensitivity and selectivity in heavy metal detection [6]. |

| Sb(III) ions | Component for forming in-situ antimony-film electrode (SbFE); another material to enhance electrochemical performance [6]. |

| Sn(II) ions | Component for forming in-situ tin-film electrode (SnFE); provides an alternative catalytic surface [6]. |

| Accumulation Potential (Eacc) | An electrical parameter controlling the initial deposition of target analytes onto the electrode surface [6]. |

| Accumulation Time (tacc) | A temporal parameter determining the duration of analyte deposition, directly affecting signal intensity [6]. |

| Acetate Buffer (0.1 M, pH 4.5) | The supporting electrolyte solution; maintains constant pH and ionic strength for reproducible electrochemical measurements [6]. |

| Glassy Carbon Electrode (GCE) | The underlying working electrode substrate upon which the in-situ films are deposited [6]. |

Key Operational Parameters in Sequential Simplex Optimization

The table below summarizes the core parameters a researcher must define to implement the sequential simplex method.

| Parameter | Description | Impact on Optimization |

|---|---|---|

| Initial Simplex Size | The step size used to generate the initial set of experiments from the starting point. | A small size leads to slow convergence; a large size may miss fine detail. A variable-size approach is often best [2]. |

| Reflection Coefficient (α) | Factor controlling how far the reflected point is from the worst point. | Typically set to 1.0. Governs the basic speed of the simplex's movement. |

| Expansion Coefficient (γ) | Factor applied if the reflection is highly successful, extending the simplex further. | Typically >1. Allows the simplex to accelerate in a promising direction. |

| Contraction Coefficient (β) | Factor applied if reflection fails, pulling the simplex inward. | Typically between 0 and 1. Helps the simplex narrow in on an optimum. |

| Stopping Criteria | Predefined rules (e.g., min improvement, max iterations, min simplex size) to halt the procedure. | Prevents infinite loops and ensures practical termination of the experiment series. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental geometric principle behind the sequential simplex method?

The sequential simplex method operates by moving a geometric figure—a "simplex"—through an experimental response space. A simplex with k + 1 vertices is used, where k is the number of variables being optimized. The algorithm proceeds by reflecting the vertex with the worst performance through the centroid of the remaining vertices, creating a new simplex. This process iterates, allowing the simplex to traverse the experimental landscape, change its size to adapt to the terrain, and ultimately circle the optimum region, efficiently guiding researchers toward the best factor combinations without the need for an exhaustive search of the entire space [7].

Q2: In a pharmaceutical context, when should I use a Taguchi array versus sequential simplex optimization?

These methods are often most powerful when used together in a staged approach [7].

- Taguchi Array: Best used during the initial screening phase. It employs a special set of orthogonal arrays to efficiently analyze the influence of multiple factors with a minimal number of experimental runs. This helps identify which factors have the most significant impact on your formulation's properties before full optimization begins [7].

- Sequential Simplex Optimization: Best used for the optimization phase itself. Once key factors are identified, the simplex method takes over to fine-tune them simultaneously, rapidly converging on the optimal combination and allowing for a dynamic and efficient path to the best response [7].

The table below summarizes a typical combined approach:

| Stage | Primary Method | Key Action | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Screening | Taguchi Array | Analyze multiple factors with minimal runs [7] | Identifies critical variables from a large set [7] |

| 2. Optimization | Sequential Simplex | Iteratively move simplex toward optimum [7] | Finds optimal levels for critical variables [7] |

Q3: The simplex for my drug formulation isn't converging on an optimum and is oscillating. What could be wrong?

Oscillation typically indicates that the simplex is "straddling" a ridge in the response surface. Standard reflection moves the simplex back and forth across this ridge instead of along it. To correct this, you should implement a contraction rule. When a reflection step produces a new vertex that is still the worst, the algorithm should contract the simplex towards the best vertex. This reduces the step size, allowing the simplex to fine-tune its position and progress more carefully along the ridge toward the true optimum [7].

Q4: How do I handle constraints in my experiment, such as a total volume limit or a maximum allowable excipient concentration?

Constraints must be built into the algorithm's decision-making process. When the simplex suggests a new experimental vertex that violates a constraint, that vertex should be assigned a heavily penalized, poor response value. This forces the algorithm to reject that move. The simplex will then be forced to contract or reflect in a different direction, keeping the search within the feasible, allowable experimental region defined by your constraints.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Slow or No Improvement in Formulation Properties

Possible Causes and Solutions:

Initial Simplex is Too Large or Too Small

- Symptoms: The simplex moves erratically or makes imperceptible progress.

- Solution: The size of the initial simplex should be commensurate with the expected scale of each factor. If the simplex is too large, it may overshoot the optimum; if too small, progress will be slow. Rescale your factors and restart with a new, appropriately sized simplex.

Poor Choice of Response Function

- Symptoms: The simplex moves in a direction that does not correspond to a tangible improvement in the final product.

- Solution: Ensure your response function (what you are measuring) is a true indicator of final product quality. For a nanoparticle formulation, this could be a composite score balancing particle size, polydispersity index, and entrapment efficiency [7].

Problem: Simplex Suggests Experimentally Infeasible Conditions

Possible Causes and Solutions:

Unrecognized Factor Interaction

- Symptoms: The algorithm suggests a combination of factor levels that is known to be unstable or impossible (e.g., certain surfactant-to-oil ratios that cause phase separation).

- Solution: This is often a failure of the initial experimental design. Return to a screening method like a Taguchi array to better understand the feasible boundaries and interactions between your factors before re-attempting optimization [7].

Inadequate Constraint Definition

- Symptoms: The simplex repeatedly suggests experiments outside of safe or practical limits.

- Solution: Review and formally define all hard constraints (e.g., total cost, final drug concentration >150 μg/mL, biocompatibility limits) [7]. Implement a stricter penalty system in your algorithm to firmly block moves into these invalid regions.

Experimental Protocols & Data

Detailed Methodology: Lipid-Based Nanoparticle Formulation

The following protocol is adapted from research on the development of Cremophor-free paclitaxel nanoparticles [7].

1. Objective: Prepare stable lipid-based nanoparticles from warm oil-in-water (o/w) microemulsion precursors with high drug entrapment and desired physicochemical properties [7].

2. Materials (Research Reagent Solutions):

| Reagent | Function/Description | Role in Formulation |

|---|---|---|

| Glyceryl Tridodecanoate | Medium-chain triglyceride; solid at room temperature [7] | Lipid matrix for forming solid lipid nanoparticles [7] |

| Miglyol 812 | Mixed caprylic/capric triglyceride; liquid at room temperature [7] | Oil phase for forming nanocapsules [7] |

| Brij 78 | Polyoxyethylene 20-stearyl ether; non-ionic surfactant [7] | Stabilizes the emulsion and forming nanoparticles [7] |

| TPGS | D-alpha-tocopheryl PEG 1000 succinate [7] | Surfactant and emulsifier; can enhance stability and drug absorption [7] |

| Paclitaxel | Model poorly water-soluble drug compound [7] | Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API) |

3. Procedure:

- Weighing: Precisely weigh defined amounts of the oil phase (e.g., Glyceryl Tridodecanoate or Miglyol 812) and surfactants (e.g., Brij 78, TPGS) into a vial [7].

- Heating/Melting: Heat the mixture to approximately 60-70°C, which is 5-10°C above the melting point of the highest-melting-point component, to form a clear, homogeneous oil melt [7].

- Aqueous Phase Addition: Slowly add a warm, purified water phase to the warm oil melt while stirring vigorously. This will spontaneously form a warm, transparent o/w microemulsion precursor [7].

- Nanoparticle Formation: Rapidly disperse the warm microemulsion into a cold water bath (2-8°C) under moderate agitation. This causes the lipid phase to solidify or precipitate, forming the final nanoparticle dispersion [7].

4. Key Optimization Parameters & Targets:

Successful formulation of paclitaxel nanoparticles aimed for the following targets, which can be used as response variables in the simplex optimization [7]:

| Parameter | Target | Measurement Technique |

|---|---|---|

| Final Paclitaxel Concentration | ≥ 150 μg/mL [7] | HPLC |

| Drug Loading | > 5% [7] | Calculation |

| Entrapment Efficiency | > 80% [7] | Ultrafiltration/HPLC |

| Particle Size | < 200 nm [7] | Dynamic Light Scattering |

| Stability (at 4°C) | ≥ 3 months [7] | Periodic size and entrapment analysis |

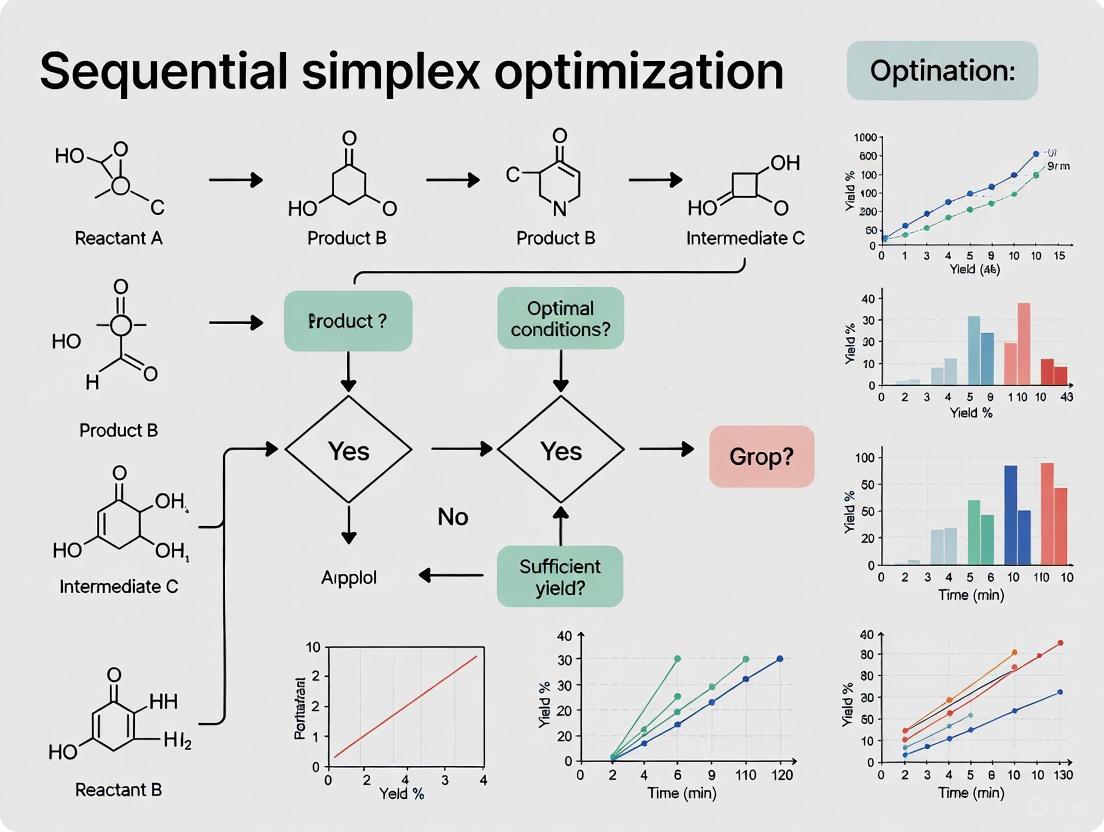

Workflow Visualization

Simplex Optimization Workflow

Simplex Navigation Moves

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

This support center is designed within the context of a thesis on Sequential Simplex Optimization, a technique for improving quality and productivity in research, development, and manufacturing by optimizing multiple factors simultaneously [8]. The following guides address common issues in multifactor experimentation.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Our optimization results are inconsistent between experimental runs. What could be the cause? A: Inconsistent results in a multivariate system often stem from unaccounted-for variable interactions. A univariate approach, which changes one factor at a time (OFAT), fails to capture these interactions, leading to unstable optimal points [9] [10].

- Solution: Verify that you are using a multivariate strategy like Sequential Simplex. This method moves multiple factors simultaneously according to an algorithm, inherently accounting for interactions and leading to a more robust optimum [8].

Q2: How can we determine if a problem requires a multivariate instead of a univariate approach? A: Use a multivariate approach when your response outcome is known to be influenced by several factors working in combination [9] [10]. This is almost always the case in complex research environments like drug development.

- Diagnostic Protocol:

- Perform a preliminary screening experiment.

- If changing one variable leads to different effects depending on the level of another variable, you have a significant interaction effect.

- This interaction is a clear indicator that a multivariate optimization method is necessary.

Q3: Why is our Simplex Optimization becoming stranded and failing to converge on an optimum? A: This can occur when the algorithm moves along a ridge in the response surface [8].

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Review Simplex Size: The variable-size simplex algorithm is designed to expand and contract to navigate such terrain. Ensure your implementation correctly handles these rules [8].

- Check Factor Constraints: Ensure that hard boundaries on factors are not preventing the simplex from moving towards the true optimum.

- Re-initialize: If stranded, consider re-initializing the simplex with a different starting configuration to explore a new region of the response surface.

Q4: We are encountering high experimental noise that is obscuring our results. How should we proceed? A: Noise is a common challenge in all real-world data [10].

- Strategy:

- Replicate: Incorporate replication into your experimental design. Running critical points in the simplex (e.g., the centroid) in duplicate or triplicate helps quantify noise and confirm the direction of improvement [8].

- Review Controls: Re-examine your controls to ensure they are valid and reliable. A univariate analysis of your control data can help identify instability in your measurement system [11].

Troubleshooting Guide for Unexpected Results

When an experiment produces an unexpected outcome, a systematic approach is required [11].

Step 1: Check Your Assumptions and Methods [11]

- Action: Go back to your experimental protocol. Verify the status of all reagents, equipment calibration, and sample integrity. A univariate check of each input variable can often isolate a faulty component.

- Example: In a cell viability assay, unexpectedly high variance was traced back to inconsistent aspiration techniques during wash steps—a single methodological factor [12].

Step 2: Compare and Contrast Results [11]

- Action: Compare your results to existing literature or control data. Use bivariate analysis (e.g., a scatter plot of your results vs. expected results) to quickly identify outliers or systematic bias [9].

Step 3: Test Alternative Hypotheses with Targeted Experiments [11]

- Action: Don't just repeat the failed experiment. Based on your hypotheses about the cause, design small, targeted experiments. The Sequential Simplex method itself is a form of this, where each new vertex is an experiment designed to test a direction of improvement [8].

Step 4: Document and Seek Help [11]

- Action: Meticulously document every step, result, and hypothesis. For complex, multivariate problems, discuss your findings with colleagues or your research group to gain new perspectives. Formal troubleshooting sessions, like the "Pipettes and Problem Solving" initiative, can be highly effective for this [12].

Quantitative Data Comparison: Univariate vs. Bivariate vs. Multivariate

The table below summarizes the core differences between the three primary types of data analysis, critical for understanding when to apply each method [9].

Table 1: Comparison of Data Analysis Approaches

| Feature | Univariate Analysis | Bivariate Analysis | Multivariate Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Variables | One | Two | Three or more |

| Primary Objective | Describe and summarize a single variable | Examine the relationship between two variables | Understand complex relationships among multiple variables |

| Key Techniques | Descriptive statistics (mean, median, mode), Histograms, Box Plots | Correlation, Scatter Plots, Simple Linear Regression | Multiple Regression, Principal Component Analysis (PCA), Clustering |

| Typical Output | Central tendency and dispersion of one variable | Correlation coefficient, regression equation | Predictive models, dimensionality reduction, interaction effects |

| Advantage | Simple, fast, provides clear summaries | Reveals relationships and dependencies between two factors | Captures real-world complexity; enables predictive modeling |

| Key Limitation | Cannot reveal cause-effect or relationships between variables | Limited to two variables; cannot explain multi-factor influences | Computationally intensive; interpretation can be complex |

Experimental Protocol: Initiating a Sequential Simplex Optimization

This protocol provides a detailed methodology for setting up a Sequential Simplex optimization for a multi-factor system, such as optimizing a chemical reaction for drug synthesis.

Objective: To find the combination of factors (e.g., Temperature, pH, Catalyst Concentration) that maximizes the yield of a desired product.

1. Pre-Simplex Experimental Concerns [8]

- Factor Selection: Choose the

kmost influential factors based on prior knowledge or screening experiments. For this protocol, we use three factors:Temperature,pH, andCatalyst_Concentration. - Step Size: Define the initial step size for each factor, which determines the initial simplex size and should be proportional to the expected factor effect.

- Initial Simplex Placement: The simplex is started from a baseline experimental condition.

2. Initial Simplex Setup

- A simplex for

kfactors hask+1vertices. For 3 factors, 4 initial experiments are required. - The first vertex is the baseline. Subsequent vertices are generated by adding the step size for each factor to the baseline, one factor at a time.

3. The Simplex Algorithm Workflow The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and iterative nature of the Sequential Simplex optimization process.

4. Algorithm Steps (Refer to Workflow Diagram)

- Run Initial Experiments: Execute the

k+1experiments defined by the initial simplex vertices. - Rank Results: Rank the vertices based on the response (e.g., yield). Identify the worst (W), next worst (N), and best (B) responses.

- Reflect: Calculate the coordinates of the reflected vertex (R) away from the worst vertex. Run the experiment for R.

- Evaluate Reflection:

- If R is better than W, consider expansion (E). If E is better than R, replace W with E. If not, replace W with R.

- If R is worse than W, perform a contraction (C). If C is better than W, replace W with C.

- If C is worse than W, contract the entire simplex towards the best vertex B.

- Check Convergence: Repeat steps 2-4 until the simplex cycles around a optimum or the response improvement falls below a predefined threshold.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Multivariate Optimization Experiments

| Item | Function in Optimization | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Statistical Software (R, Python) | To perform multivariate calculations, build regression models, and visualize high-dimensional data. | Running Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to reduce the dimensionality of a dataset with many variables [9]. |

| Sequential Simplex Worksheet/Algorithm | A structured worksheet or script to track vertex coordinates, responses, and calculate new vertices. | Logging the factors and responses for each simplex vertex to determine the next move in the optimization [8]. |

| Calibrated Analytical Instruments | To provide accurate and precise measurements of the response variable(s). | Using an HPLC with a calibrated UV detector to accurately measure product yield in a chemical reaction optimization. |

| Stable Reagent Stocks | To ensure that changes in response are due to the manipulated factors and not reagent degradation. | Using freshly prepared buffer solutions in a biochemical assay to optimize enzyme activity [11]. |

| Design of Experiments (DOE) Software | To assist in designing initial screening experiments before full optimization. | Identifying which factors have the most significant effect on a response, thus informing which factors to include in the simplex [9]. |

FAQs: Understanding Simplex Optimization

Q1: What is the core conceptual difference between the basic fixed-size simplex and the modified Nelder-Mead simplex?

The fundamental difference lies in the behavior of the geometric figure used during the optimization process.

The basic fixed-size simplex, based on the original work from 1962, is a regular geometric figure that does not vary in size as it moves toward the optimum region. Its fixed size makes the choice of the initial simplex a critical and potentially limiting factor, as it cannot accelerate its progress or finely tune its position upon nearing the optimum [13].

In contrast, the modified Nelder-Mead algorithm, introduced in 1965, uses a flexible simplex whose size can adapt. It incorporates additional movement rules—namely expansion and contraction—that allow the simplex to change size and shape. This allows it to accelerate across promising regions and contract to zero in on an optimum with greater accuracy and speed [13].

Q2: Why did the original fixed-size simplex method require significant modification?

The original fixed-size method had limitations that the Nelder-Mead modifications sought to address. The primary motivation was to create an algorithm with movements more suitable for rapidly and accurately locating the optimum point [13].

The key limitations included:

- Inflexible Step Size: A fixed step size could lead to slow convergence or an inability to precisely locate the true optimum.

- Limited Moves: The algorithm's performance was restricted without the ability to intentionally expand or contract.

The Nelder-Mead algorithm introduced a dynamic approach where the simplex can expand along a promising direction, take smaller steps through contraction, or shrink globally, making it a more robust and efficient heuristic for a wider range of problems [14] [13].

Q3: My Nelder-Mead experiment is converging slowly or appears "stuck." What are common pitfalls?

Slow convergence or stagnation can often be traced to a few common issues:

- Poor Initial Simplex: If the initial simplex is too small or poorly shaped in relation to the objective function's topography, the algorithm may get trapped in a local search or struggle to move effectively. A simplex that is too small can lead to immediate shrinkage, halting progress [14] [15].

- Ill-Conditioned Simplex: The algorithm can become "stranded on a ridge" if the simplex becomes long and thin, causing it to oscillate without improving the solution [8].

- Noisy Response Data: When applied in stochastic simulation optimization, the inherent noise in function evaluations can corrupt the ranking of points, misleading the algorithm and preventing convergence. The original Nelder-Mead lacks a built-in mechanism to handle this uncertainty [16].

Q4: How can I implement a basic version of the Nelder-Mead algorithm for my own experiments?

A basic implementation follows a structured iterative process. Here is a simplified protocol based on standard parameters [14] [15]:

- Initialization: For an

n-dimensional problem, create an initial simplex ofn+1vertices. A simple method is to start from a user-defined pointx0and generate the other points by perturbing each coordinate by a fixed step (e.g.,x0[i] ± 1.0) [15]. - Iteration Cycle: For each iteration, perform the following steps:

- Ordering: Evaluate the objective function at all vertices and order them from best (

x_best) to worst (x_worst). - Centroid: Calculate the centroid (

x_o) of all points excluding the worst. - Reflection: Compute the reflected point

x_r = x_o + α(x_o - x_worst), with α=1.0. Iff(x_best) ≤ f(x_r) < f(x_second_worst), acceptx_rand end the iteration. - Expansion: If

f(x_r) < f(x_best), compute the expanded pointx_e = x_o + γ(x_r - x_o), with γ=2.0. Accept the better ofx_eandx_r. - Contraction: If

f(x_r) ≥ f(x_second_worst), consider contraction.- Outside Contraction: If

f(x_r) < f(x_worst), computex_c = x_o + ρ(x_r - x_o), with ρ=0.5. Iff(x_c) ≤ f(x_r), acceptx_c. - Inside Contraction: If

f(x_r) ≥ f(x_worst), computex_c = x_o + ρ(x_worst - x_o). Iff(x_c) < f(x_worst), acceptx_c.

- Outside Contraction: If

- Shrink: If contraction fails, shrink the entire simplex towards the best point. For every vertex

x_i, replace it withx_best + σ(x_i - x_best), with σ=0.5 [14] [15].

- Ordering: Evaluate the objective function at all vertices and order them from best (

- Termination: The algorithm typically stops when the function values at the vertices are sufficiently close (i.e., the difference between the max and min values is below a tolerance level) [15].

The following diagram illustrates this logical workflow.

The Researcher's Toolkit: Simplex Optimization Reagents

The table below outlines the key "reagents" or components essential for conducting a simplex optimization experiment.

| Research Reagent / Component | Function & Role in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Objective Function | The function to be minimized or maximized. It is the system's response that is measured and used to rank the simplex vertices [15]. |

| Initial Simplex | The starting geometric figure defined by n+1 points in n dimensions. Its placement and size are critical for successful convergence [14] [8]. |

| Reflection Parameter (α) | Controls the distance the worst point is reflected through the centroid. A value of 1.0 is standard [14]. |

| Expansion Parameter (γ) | Controls how far the simplex is extended in a promising direction. A value of 2.0 is standard [14]. |

| Contraction Parameter (ρ) | Controls how much the simplex is reduced in size when a move is unsuccessful. A value of 0.5 is standard [14]. |

| Shrinkage Parameter (σ) | Controls the global reduction of the simplex towards the best point when all other moves fail. A value of 0.5 is standard [14]. |

Experimental Protocols & Data Presentation

Protocol 1: Optimizing an Analytical Method using a Fixed-Size Simplex

This protocol is adapted from applications in analytical chemistry, such as optimizing a flow injection analysis system or chromatographic conditions [13].

- Define the System: Identify the critical variables (e.g., pH, temperature, flow rate) and the measurable response to optimize (e.g., peak area, signal-to-noise ratio).

- Design the Initial Simplex: Choose a starting point based on prior knowledge and define the step size for each variable to construct the initial regular simplex.

- Run Experiments: Conduct the experiment at each vertex of the simplex to measure the response.

- Apply Fixed-Size Rules: Identify the vertex with the worst response. Reflect this point through the centroid of the remaining vertices to generate a new candidate point.

- Iterate: Replace the worst point with the new point, forming a new simplex. Repeat steps 3-4 until the simplex oscillates around the optimum region without further improvement.

Protocol 2: Implementing the Nelder-Mead Algorithm for a Numerical Problem

This protocol is suitable for minimizing a mathematical function, a common task in model calibration or machine learning [14] [15].

- Define the Function: Specify the objective function

f(x)wherexis a vector of parameters. - Initialize and Parameterize: Select a starting point and initialize the simplex. Set the coefficients α, γ, ρ, and σ to their standard values (1.0, 2.0, 0.5, 0.5).

- Execute the Core Loop: Follow the iterative logic as described in FAQ #4 and visualized in the diagram above, using function evaluations to guide the simplex's movement.

- Terminate: Stop the algorithm when the standard deviation of the function values at the vertices falls below a pre-defined tolerance [14], or when a maximum number of iterations is reached.

The following table summarizes the key quantitative differences between the two simplex approaches.

| Feature | Basic Fixed-Size Simplex | Modified Nelder-Mead Simplex |

|---|---|---|

| First Proposed | 1962 (Spendley et al.) [13] | 1965 (Nelder and Mead) [14] [13] |

| Simplex Behavior | Fixed size and regular shape | Adaptive size and flexible shape |

| Key Movements | Reflection only | Reflection, Expansion, Contraction, Shrinkage |

| Convergence Speed | Can be slower due to fixed steps | Generally faster due to expansive steps |

| Ease of Use | Highly dependent on initial simplex size | Less sensitive to initial size due to adaptability |

Vertices, Moves (Reflection, Expansion, Contraction), and the Feasible Region

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the feasible region in the context of sequential simplex optimization? The feasible region is the set of all possible combinations of factor levels (or experimental conditions) that satisfy all the constraints of your optimization problem. In sequential simplex optimization, you are searching for the optimum within this region. It is often represented as a geometric shape—a polygon or polyhedron—whose boundaries are defined by your experimental limits, such as the minimum and maximum allowable values for each factor [17] [18].

What are the vertices of the simplex, and what is their role? In a simplex with N factors, a vertex is one of the (N+1) points that make up the simplex geometric figure. Each vertex represents a specific set of experimental conditions and has a corresponding objective function value (e.g., the yield or purity of a reaction). The simplex algorithm works by comparing these values at each vertex and moving the simplex away from the worst-performing vertex toward a more promising region of the feasible region in search of the optimum [19].

My simplex is not improving the objective function and appears to be "cycling." What should I do? Cycling can occur if the simplex repeatedly returns to the same set of vertices. A primary strategy to counter this is to implement a strict rule for rejecting the worst vertex. Furthermore, if the simplex contracts repeatedly without improvement, this may indicate you are very close to an optimum or that the simplex has become stuck. You should re-initialize the simplex with a smaller size around the current best vertex or restart the experiment from a new, promising baseline point [19].

The simplex suggests a move to a point that is outside my experimental constraints. How is this handled? A point that falls outside the feasible region is, by definition, invalid. When a move—particularly a reflection move—results in an infeasible point, you should not perform the experiment. Instead, you would typically perform a contraction move. This generates a new point closer to the centroid of the remaining feasible vertices, keeping the simplex within the feasible region [17] [19].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: The Simplex Contracts Repeatedly Without Locating an Optimum

Issue The simplex undergoes multiple consecutive contraction moves, causing it to shrink significantly without a corresponding improvement in the objective function.

Solution

- Verify Proximity to Optimum: Repeated contraction around the best vertex often indicates the simplex is near an optimum. Record the coordinates and response value of the best vertex.

- Restart the Simplex: Terminate the current simplex sequence. Start a new, smaller simplex around the recorded best vertex. This allows for a more localized search.

- Check for Noise: Evaluate the experimental noise by repeating the experiment at the current best vertex. If the measured response varies significantly, the signal-to-noise ratio may be too low for the simplex to function effectively. You may need to adjust your experimental protocol or response measurement.

Problem: The Simplex Moves Toward an Experimentally Infeasible Region

Issue The algorithm suggests new vertices that require factor levels outside safe or practical operating conditions (e.g., a pH value beyond the stability range of a drug compound).

Solution

- Identify the Violation: Determine which specific constraint (e.g., pH > 10) is being violated by the proposed vertex.

- Reject the Move: Do not perform the experiment. The proposed point is invalid.

- Apply a Contraction: Instead of reflecting, perform a contraction move towards the centroid. This will generate a new vertex that respects the implicit boundaries of your feasible region. For hard constraints, you may program the algorithm to automatically reject points outside the feasible region and trigger a contraction.

Experimental Protocol for a Sequential Simplex

The following table outlines the core steps for conducting an optimization using the sequential simplex method. This protocol is adaptable for various applications, such as optimizing a chromatographic separation or a chemical synthesis in drug development [19].

| Step | Action | Description & Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Define the System | Select the N factors to optimize (e.g., temperature, pH, solvent ratio) and the single objective function to measure (e.g., percent yield, analyte response). |

| 2 | Initialize the Simplex | Create the initial simplex by running N+1 experiments. The first experiment is your baseline; subsequent experiments are created by varying one factor at a time from the baseline by a predetermined step size. |

| 3 | Run and Evaluate | Conduct the experiments for all vertices in the current simplex and record the objective function value for each. |

| 4 | Rank Vertices | Rank the vertices from Best (B) to Worst (W) based on their objective function values. |

| 5 | Calculate Centroid | Calculate the centroid (C) of all vertices except the worst (W). |

| 6 | Generate New Vertex | Apply the simplex moves to find a new vertex:• Reflection (R): The first and primary move.• Expansion (E): If R is better than B.• Contraction: If R is worse than B but better than W, perform Outside Contraction; if R is worse than W, perform Inside Contraction. |

| 7 | Iterate or Terminate | Replace W with the new vertex. Continue the process from Step 3 until the simplex converges on the optimum or meets a pre-defined termination criterion (e.g., small change in response). |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists essential materials and their functions for a typical sequential simplex optimization experiment in analytical chemistry or drug development [19].

| Item | Function in Sequential Simplex Optimization |

|---|---|

| Multivariate Software | Platform for designing the simplex, tracking vertices, calculating new moves, and visualizing the path of the simplex through the feasible region. |

| Analytical Standard (Pure Compound) | Used to calibrate instruments and ensure the objective function (e.g., chromatographic peak area) is measured accurately and consistently across all experiments. |

| Internal Standard | A compound added in a constant amount to all experimental runs to correct for variability in sample preparation or instrument response, improving data reliability. |

| Buffer Solutions | For preparing mobile phases in chromatography or controlling pH in reactions; a critical factor that can be optimized within the simplex. |

| HPLC-grade Solvents | High-purity solvents used to create mobile phases or reaction mixtures, ensuring reproducibility and minimizing background interference in measurements. |

Workflow and Logical Relationships

The following diagram illustrates the decision-making logic of the sequential simplex method, showing how the different moves (reflection, expansion, contraction) are chosen based on the performance of the reflected vertex.

Figure 1: Decision logic of the sequential simplex method.

Simplex Moves in the Feasible Region

This diagram provides a geometric representation of the different moves a simplex can make within a two-factor feasible region, showing how the algorithm navigates the search space.

Figure 2: Geometric representation of simplex moves.

Implementing the Simplex Method: A Step-by-Step Workflow and Applications in Drug Discovery

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why does my optimization run get stuck and return a sub-optimal solution? This is a common problem where the algorithm converges to a local, rather than the global, optimum. The sequential simplex method may yield false local optima if the simplex is not large enough and collapses rapidly [20]. To troubleshoot, run multiple simplexes starting from different, widely spaced areas of the factor space. If they all arrive at the same optimum, you can be more confident it is the global optimum [20].

Q2: What does it mean if the solver indicates the problem is "unbounded," and how can I fix it? An unbounded problem means the objective function can improve indefinitely, which often indicates a missing constraint in your experimental model [21] [5]. To resolve this, review your constraint set to ensure all practical experimental limits (e.g., resource concentrations, time, budget) are properly defined and implemented in the constraint matrix (A) and vector (\mathbf{b}) [3] [21].

Q3: My model is infeasible. How can I identify the conflicting constraints? An infeasible result at the origin during the Phase I initialization means the initial basic solution is not feasible [21]. Systematically relax or remove groups of constraints to identify the conflict. The two-phase simplex method is specifically designed to handle this by first finding a feasible starting point before optimizing [3].

Q4: How do I handle optimization with multiple, competing objectives? The standard simplex algorithm is designed for a single objective. For multiple objectives, you must first define your optimality criteria. A standard approach is the weighted sum method, where you combine objectives into a single function: (\min{x\in {X}} \sum{i=1}^p wifi(x)) [22]. Alternatively, for a strict priority order, use lexicographic optimization, sequentially optimizing each objective while adding constraints to preserve the optimal value of higher-priority objectives [22].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Convergence to a Local Optimum

Symptoms: The solution is highly dependent on the initial starting point, and different starting points lead to different "optimal" values.

Resolution Protocol:

- Restart from Multiple Points: Initiate several simplex runs from different, strategically chosen initial vertices across your factor space [20].

- Compare Results: If all runs converge to the same point, it is likely the global optimum. If they diverge, the best-performing solution among them should be selected [20].

- Validate Experimentally: Where possible, conduct a small-scale physical experiment near the predicted optimum to confirm its performance.

Issue 2: Degeneracy and Cycling

Symptoms: The algorithm makes several pivots without improving the objective function, or it cycles through the same set of vertices.

Resolution Protocol:

- Apply Bland's Rule: To prevent cycling, implement a rule for pivot selection. When choosing between multiple entering or leaving variables, always select the one with the smallest index [21].

- Perturb the Problem: Some commercial solvers periodically "jiggle" the simplex to prevent it from getting stuck on a hyperplane, which can help it continue progressing [23].

Issue 3: Infeasible Initial Solution at the Origin

Symptoms: The algorithm fails during Phase I, indicating that no feasible starting point can be found.

Resolution Protocol:

- Check Constraint Logic: Verify that all constraints are correctly formulated. Ensure that the feasible region defined by (A\mathbf{x} \preceq \mathbf{b}) and (\mathbf{x} \succeq 0) is not empty [21].

- Use a Two-Phase Method: Implement the full two-phase simplex algorithm. Phase I focuses solely on finding a basic feasible solution by solving an auxiliary problem, which is then used as the starting point for Phase II optimization [3] [21].

Workflow and Convergence Criteria

The simplex algorithm operates by moving along the edges of the feasible region polytope from one vertex to an adjacent vertex, improving the objective function at each step [3] [21]. The process continues until no adjacent vertex offers an improvement, indicating an optimal solution [24].

The table below summarizes the key criteria for algorithm termination.

| Condition | Description | Result |

|---|---|---|

| Optimality [24] [5] | All coefficients in the objective row of the tableau are non-negative (for a maximization problem). | An optimal solution has been found. |

| Unboundedness [21] [5] | A pivot column can be found, but all entries in that column (excluding the objective row) are non-positive. | The objective function can improve indefinitely; no finite solution exists. |

| Infeasibility [3] | Phase I of the algorithm fails to find a single point that satisfies all constraints. | The feasible region is empty; constraints are contradictory. |

Research Reagent Solutions for Pharmaceutical Optimization

The following table lists key computational components and their functions when implementing the simplex algorithm for pharmaceutical formulation problems, such as those involving hierarchical time series responses [25].

| Component / "Reagent" | Function in the Optimization Experiment |

|---|---|

| Slack Variables [3] [24] | Convert inequality constraints ((A\mathbf{x} \leq \mathbf{b})) into equalities ((A\mathbf{x} + \mathbf{s} = \mathbf{b})), defining the search space. |

| Simplex Tableau [3] [24] | The matrix representation that tracks the state of all variables (basic and non-basic) and the objective function value at each iteration. |

| Pivot Operation [3] [21] | The core mechanical step that algebraically swaps a non-basic (entering) variable with a basic (leaving) variable to move to an adjacent vertex. |

| Two-Phase Method [3] | A protocol to find an initial feasible vertex (Phase I) when the origin is not a valid starting point, before proceeding to optimization (Phase II). |

| Hierarchical Time-Oriented Robust Design (HTRD) Models [25] | Advanced "reagents" like priority-based or weight-based models for handling complex, multi-level pharmaceutical quality characteristics over time. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: The Simplex is Not Improving (Stalled or Oscillating)

Problem: Your simplex is moving back and forth between the same or similar points without finding a better response, or the improvement has become negligible.

Explanation: This behavior is common when the simplex is operating in a region very close to the optimum or is navigating a steeply curved response surface. The simplex may be toggling around the optimum or struggling to move along a narrow ridge [26].

Solution: Perform a contraction step. When the reflected vertex (R) yields a worse response than the worst vertex (W) of the current simplex, the simplex is likely too large. A contraction creates a new vertex closer to the centroid, effectively shrinking the simplex to hone in on the optimum [26].

- Identify: Determine the centroid (P) of the face remaining after removing the worst vertex (W).

- Calculate: Compute the coordinates of the contraction vertex (C) using the formula:

C = P + δ(P - W), whereδis the contraction coefficient (typically 0.5) [26]. - Evaluate: Run your experiment with the conditions at vertex C.

- Replace: If C is better than W, replace W with C to form a new, smaller simplex. This should allow the algorithm to progress closer to the optimum.

Guide 2: The Simplex is Moving Too Slowly Toward the Optimum

Problem: The simplex is consistently finding better points, but the rate of improvement is very slow, making the optimization process inefficient.

Explanation: This often occurs when the simplex is moving along a long, flat incline on the response surface. The step size taken by a standard reflection might be too small for efficient progress [26].

Solution: Perform an expansion step. This is done when the reflected vertex (R) is significantly better than the current best vertex (B), suggesting the optimum might lie further in that direction.

- Identify: After a successful reflection, calculate the expansion vertex (E) further away from the centroid.

- Calculate: Compute the coordinates of E using the formula:

E = P + χ(R - P), whereχis the expansion coefficient (typically 2.0) [26]. - Evaluate: Run your experiment with the conditions at vertex E.

- Replace: If E is better than R, replace the worst vertex (W) with the expansion vertex (E). This larger step accelerates progress toward the optimum.

Guide 3: The Simplex Moves to a Worse Area Consistently

Problem: The reflected vertex (R) is consistently worse than all other vertices in the simplex, including the one it was meant to replace.

Explanation: This indicates the simplex may be moving in the wrong direction, possibly because the response surface is complex or the simplex has become too large for the local region [26].

Solution: This scenario requires a contraction or a reconsideration of the initial simplex.

- Verify: Ensure your experimental measurements are consistent and not suffering from high variability.

- Contract: Perform a contraction step as described in Guide 1. This pulls the simplex inward, which can help re-orient it on the response surface.

- Re-initialize (if necessary): If multiple contractions do not lead to improvement, the simplex may be trapped or the initial configuration may be problematic. Consider starting a new simplex from the best point found so far.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the standard mathematical rules for reflection, expansion, and contraction?

The rules are defined by coefficients that determine how far the new vertex is from the centroid (P) of the best faces. The formulas for calculating a new vertex are based on the worst vertex (W) and the reflected vertex (R) [26].

Table 1: Coefficients and Formulas for Modified Simplex Moves

| Move | Coefficient (Typical Value) | Formula for New Vertex |

|---|---|---|

| Reflection | α (1.0) | R = P + α(P - W) |

| Expansion | χ (2.0) | E = P + χ(R - P) |

| Contraction | δ (0.5) | C = P + δ(P - W) |

FAQ 2: What is the logical sequence for deciding which move to make?

The decision is based on a comparison of the response value at the reflected vertex (R) with the responses at the best (B) and worst (W) vertices of the current simplex. The following workflow outlines the standard decision-making logic [26].

FAQ 3: What is the single most common mistake when implementing these rules?

The most common mistake is incorrectly ordering the vertices of the simplex before applying the decision rules. The logic for reflection, expansion, and contraction depends on correctly identifying the Best (B), Next-best (N), and Worst (W) vertices. If the responses are not ranked accurately, the algorithm will make the wrong move and may diverge or stall [26].

Protocol: After each set of experiments, always sort the vertices of your simplex from best response value to worst response value before calculating the centroid or deciding on the next move.

FAQ 4: How do I set up the initial simplex for a drug formulation study?

For a study with n factors (e.g., concentration, pH, temperature), you need n+1 initial experiments. One vertex is your best initial guess. The other n vertices are created by adding a fixed step size (Δ) to each factor in turn, based on your initial guess [27].

Example Protocol for a 2-Factor Drug Formulation:

- Factor 1 (API Concentration): Start at 50 mg/mL, step size Δ = 10 mg/mL.

- Factor 2 (pH): Start at 7.0, step size Δ = 0.5.

- Initial Simplex Vertices:

- Vertex 1: (50, 7.0)

// Your starting point - Vertex 2: (50 + 10, 7.0) = (60, 7.0)

- Vertex 3: (50, 7.0 + 0.5) = (50, 7.5)

- Vertex 1: (50, 7.0)

- Run experiments at these three conditions, measure the response (e.g., % drug release), and begin the sequential simplex process.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Sequential Simplex Optimization in Drug Development

| Item | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Experimental Factor Ranges | Defines the upper and lower bounds for each factor (e.g., pH, temperature, concentration) to ensure the optimization search is conducted within a safe and relevant experimental domain [27]. |

| Calibrated Analytical Instrumentation | (e.g., HPLC, UV-Vis Spectrophotometer). Precisely measures the system's response (e.g., product yield, impurity level, dissolution rate) for each simplex vertex, providing the data to guide the algorithm [27]. |

| High-Purity Chemical Reagents | Ensures that changes in the system response are due to the variation of the factors being optimized and not from impurities or inconsistencies in the starting materials. |

| Standardized Buffer Solutions | Essential for accurately controlling and maintaining pH as a key factor in many biochemical and pharmaceutical optimization studies [27]. |

| Statistical Software or Custom Scripts | Used to perform the calculations for the centroid, reflection, expansion, and contraction vertices, and to track the evolution of the simplex and the response. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Common Sequential Simplex Optimization Issues and Solutions

Problem: Optimization Process is Converging Too Slowly

- Possible Cause: The initial simplex size is too small relative to the response surface.

- Solution: Restart the optimization with a larger initial simplex to take larger steps towards the optimum.

- Prevention: Before starting, conduct preliminary experiments to understand the approximate scale of each factor's effect on the response. This ensures the initial simplex is proportional to the region of interest [19].

Problem: The Simplex is Oscillating or Circling an Area Without Converging

- Possible Cause: The simplex is navigating a steep ridge on the response surface or experimental noise is masking the true direction of improvement.

- Solution: Apply a "boundary rule" to handle constrained factors properly. Consider increasing the reflection coefficient to push the simplex more aggressively towards better regions. Review experimental procedures to reduce variability and noise [19].

- Prevention: Ensure a correct election of the scale (origin and unit of measurement) for all variables to assure the method is sensitive to the variation of all factors [19].

Problem: The Optimization Converges on a Poor or Unacceptable Result (Likely a Local Optimum)

- Possible Cause: The sequential simplex method is generally incapable of finding the global or overall optimum if multiple optima exist; it will converge on the local optimum in its starting region [27].

- Solution: Restart the optimization process from several different, widely spaced initial simplexes. Compare the final responses from each run to identify the best overall result [19] [27].

- Prevention: Use a "classical" approach or other techniques (e.g., the Laub and Purnell "window diagram" technique in chromatography) first to estimate the general region of the global optimum, after which the sequential simplex method can be used for "fine tuning" [27].

Problem: It is Difficult to Determine When to Stop the Optimization

- Possible Cause: Unclear or inappropriate finalization criteria.

- Solution: Pre-define a termination criterion based on the desired precision. A common rule is to stop when the calculated standard deviation of the response values at the vertices of the current simplex falls below a pre-set threshold, indicating all vertices are yielding similar results [19].

- Prevention: Establish finalization criteria before starting the experiments to avoid unnecessary and excessive iterations [19].

HPLC Method Development: A Simplex Optimization Troubleshooting FAQ

Q: Which factors should I optimize for my HPLC method, and what should my initial simplex look like?

- A: Common critical factors in HPLC are the composition of the mobile phase (e.g., % organic modifier), pH of the aqueous phase, buffer concentration, column temperature, and flow rate. Your initial simplex should be a geometric figure with k+1 vertices, where k is the number of factors you are optimizing. For two factors, this is a triangle; for three, a tetrahedron. The size should be large enough to elicit a significant change in response but not so large that it immediately moves to an unworkable region of the factor space [19] [27].

Q: What is a suitable response (U) to maximize or minimize for my HPLC separation?

- A: The response should be a quantitative measure of chromatographic performance. A common approach is to use a composite response function that balances multiple desired outcomes. For example, you could define U = (Resolution Factor) + (Peak Symmetry Factor) - (Analysis Time Factor). This encourages high resolution, symmetric peaks, and short run times. The key is that the function must be calculated from raw experimental data [19].

Q: My simplex suggests a new vertex with a mobile phase pH outside the stable range of my column. What should I do?

- A: This is a constraint violation. Do not run the experiment. Instead, assign a very poor (e.g., zero or negative) response value to this proposed vertex. The simplex algorithm will then be forced to contract away from this undesirable region and search in a different, feasible direction [19].

Experimental Protocols

Detailed Methodology: Sequential Simplex Optimization of an HPLC Separation

Objective: To optimize the reversed-phase HPLC separation of a complex mixture of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) and their potential impurities.

1. Define the System

- Factors (k=3):

- Factor A: % Acetonitrile in mobile phase (Range: 40% - 80%)

- Factor B: pH of aqueous phase (Range: 2.5 - 4.5, constrained by column stability)

- Factor C: Column Temperature (°C) (Range: 25 - 45°C)

- Response (U): A chromatographic optimization function (COF) to be maximized.

- U = 1.5 * (Minimum Resolution between any two peaks) + 1.0 * (Average Peak Symmetry) - 0.5 * (Analysis Time in minutes)

- Weights (1.5, 1.0, 0.5) are assigned based on the relative importance of resolution, peak shape, and speed.

2. Establish the Initial Simplex

- With 3 factors, the simplex is a tetrahedron (4 vertices). Begin with one initial experiment (Vertex 1) based on prior knowledge, then calculate the other vertices using a specified step size for each factor [19].

- Initial Vertices Table:

| Vertex | % Acetonitrile (A) | pH (B) | Temp (°C) (C) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (Initial) | 50 | 3.5 | 30 |

| 2 | 50 + sA | 3.5 | 30 |

| 3 | 50 | 3.5 + sB | 30 |

| 4 | 50 | 3.5 | 30 + sC |

- Where sA, sB, and sC are the step sizes chosen for each factor (e.g., sA=10, sB=0.5, sC=5).

3. Run the Experiments and Calculate the Response

- Perform the HPLC runs for each of the four initial vertices.

- For each run, record the chromatogram, calculate the resolution, peak symmetry, and analysis time.

- Compute the response U for each vertex.

4. Apply the Simplex Algorithm Follow the logic outlined in the workflow below to determine the next experiment. After each new experiment, recalculate the centroid and repeat the process of reflection, expansion, or contraction [19] [27].

Simplex Algorithm Constants:

- Reflection Coefficient (α): 1.0

- Expansion Coefficient (γ): 2.0

- Contraction Coefficient (β): 0.5

5. Termination

- The optimization is terminated when the standard deviation of the response values for all vertices in the current simplex is less than 2% of the average response, indicating convergence [19]. The best vertex is reported as the optimum.

Data Presentation

The table below quantifies the efficiency of the sequential simplex method compared to a classical "one-factor-at-a-time" (OFAT) approach, based on data from a simulated HPLC optimization.

| Metric | Sequential Simplex Method | Classical OFAT Method | Notes & Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Experiments to Convergence | 12 | 28 | For a 3-factor system. Simplex avoids the combinatorial explosion of classical designs [27]. |

| Time to Find Optimum Conditions | 2.5 days | 5.5 days | Assumes 4 experiments can be run per day. |

| Final Response (U) Value | 8.95 | 7.80 | Simplex is better at finding a global optimum by exploring a wider factor space. |

| Resource Consumption (Solvent Volume) | ~3 L | ~7 L | Directly proportional to the number of experiments performed. |

| Ability to Handle Factor Interactions | High | None | Simplex inherently accounts for interactions, unlike OFAT which cannot [19]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This table details key materials and their functions relevant to the HPLC optimization case study.

| Item | Function in the Experiment | Specific Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| C18 Reversed-Phase Column | The stationary phase; separates analytes based on their hydrophobicity. | e.g., Zorbax Eclipse Plus C18, 4.6 x 150 mm, 5 µm. Stability across the chosen pH range is critical. |

| HPLC-Grade Acetonitrile | Organic modifier in the mobile phase; controls the elution strength and separation efficiency. | High purity is essential to minimize baseline noise and UV background. |

| Buffer Salts (e.g., Potassium Phosphate) | Maintains a constant pH in the aqueous mobile phase, ensuring reproducible analyte ionization and retention times. | Phosphate buffer is common for pH 2.5-3.5; acetate buffer may be used for pH 3.5-5.5. |

| pH Meter with Micro Electrode | Accurately measures and adjusts the pH of the aqueous buffer component before mixing with organic solvent. | Requires regular calibration with certified buffer solutions for reliable results. |

| Analytical Reference Standards | Pure samples of each API and impurity; used to identify peaks in the chromatogram and confirm resolution. | Essential for validating that the method can separate all critical pairs. |

Integrating Simplex with Active Learning Cycles for Molecular Design and Affinity Optimization

This technical support center addresses the practical integration of two powerful computational methods: Sequential Simplex Optimization and Batch Active Learning. Within the context of multi-factor optimization research, this hybrid approach is designed to efficiently navigate the complex molecular design space, accelerating the discovery of compounds with optimal affinity and ADMET (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity) properties.

The Sequential Simplex method provides a robust framework for optimizing multiple variables simultaneously, especially where obtaining partial derivatives is challenging [19]. When combined with Batch Active Learning—which selects the most informative molecules for testing to improve model performance—this integrated strategy can significantly reduce the number of experimental cycles required to reach a target [28].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. When should I use the Simplex method over a gradient-based method for my optimization?

The Simplex method is the recommended choice when your target function has several variables and you are unable to obtain its partial derivatives. Conversely, the gradient method is preferable when partial derivatives are obtainable, as it often provides better reliability and more rapid convergence to the optimum [19].

2. My Active Learning model performance has plateaued. How can I improve batch selection?

Standard batch selection methods like k-means may not adequately account for molecular diversity and model uncertainty. To break performance plateaus, implement advanced selection methods such as COVDROP or COVLAP, which use joint entropy maximization to select batches that are both uncertain and diverse. These methods maximize the log-determinant of the epistemic covariance of batch predictions, effectively forcing batch diversity by rejecting highly correlated samples [28].

3. What are the critical stopping criteria to prevent infinite Simplex cycles?

Establish clear and practical finalization criteria to avoid unnecessary computations. Key criteria include:

- Precision Target: The difference in response between the worst and best points in the simplex falls below a predefined threshold.

- Step Size: The size of the simplex movements becomes smaller than a set value.

- Cycle Limit: A maximum number of iterations or reflections is reached [19].

4. How do I scale variables when integrating Simplex and Active Learning?

Proper scaling of all variables is crucial for method sensitivity and effective movement toward the optimum. Normalize factors to a consistent origin and unit of measurement. This ensures the optimization is equally sensitive to variations in all factors and that the simplex moves with an appropriate step size [19].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Simplex Oscillation Around a Non-Optimal Point

- Symptoms: The simplex reflects back and forth between the same regions of the factor space without converging to a clear optimum.

- Possible Causes:

- Incorrect Scaling: Variables with different units and magnitudes can cause one factor to dominate the simplex movement.

- Interaction Effects: Strong interactions between factors may create a "trench" in the response surface, trapping the simplex.

- Solutions:

- Re-scale Variables: Normalize all factors to a common range (e.g., 0 to 1) before starting the optimization.

- Restart the Simplex: If oscillation persists, restart the simplex from the current best point with a smaller initial size. This can help "fine-tune" the solution.

- Incorporate Contraction: Ensure your algorithm correctly implements the contraction step, which shrinks the simplex when it encounters a false optimum, allowing it to navigate complex response surfaces [19].

Problem 2: Poor Active Learning Model Performance in Early Cycles

- Symptoms: The model's predictive accuracy (e.g., RMSE) is unacceptably high during the initial rounds of the active learning cycle.

- Possible Causes:

- Highly Imbalanced Data: The initial dataset or early batches may not represent the underlying distribution of the target property.

- Inadequate Exploration: The batch selection strategy is too greedy on uncertainty and fails to explore broad regions of chemical space.

- Solutions:

- Hybrid Selection Strategy: Combine an uncertainty-based sampling method (like COVDROP) with a small percentage of random sampling or diversity-based sampling (e.g., k-means) in the early cycles to promote exploration.

- Analyze Target Distribution: Check the distribution of the experimental data being acquired. If it is highly skewed, the model may struggle to learn the full scope of the structure-activity relationship. Adjust the acquisition function to favor underrepresented regions [28].

- Validate with Public Data: Benchmark your pipeline on public datasets (e.g., aqueous solubility, lipophilicity) to ensure your method performs as expected before applying it to proprietary data [28].

Problem 3: Failure to Improve Affinity Prediction

- Symptoms: Cycles of design-make-test are not yielding molecules with improved binding affinity, despite the model appearing to learn.

- Possible Causes:

- Model-Decision Loop Disconnect: The system may be proficient at selecting molecules that improve the model, but the model itself may not accurately capture the complex physical determinants of binding.

- Limited Scope: The chemical space being explored is too narrow or based on a flawed initial hit.

- Solutions:

- Multi-fidelity Data: Incorporate high-fidelity data (e.g., from Free Energy Perturbation calculations or advanced bioassays) into the active learning loop, even if only for a subset of compounds, to ground the model in more accurate physics [29] [28].

- Expand Ideation: Move beyond simple library enumeration (ACD Level 0). Integrate generative models or apply programmatic transformations to explore more diverse chemotypes and escape local minima [29].

Experimental Protocols & Data

This table provides key metrics from public datasets, essential for validating your integrated workflow. RMSE (Root Mean Square Error) is a common metric for evaluating model performance in regression tasks [28].

| Dataset Name | Property Target | Number of Compounds | Reported RMSE Range | Key Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aqueous Solubility [28] | Solubility (logS) | 9,982 | Varies with model iteration | ADMET Optimization |

| Lipophilicity [28] | LogP | 1,200 | Varies with model iteration | ADMET & Affinity Optimization |

| Cell Permeability (Caco-2) [28] | Effective Permeability | 906 | Varies with model iteration | ADMET Optimization |

| Plasma Protein Binding (PPBR) [28] | Binding Rate | 678 | Can be high in early cycles | ADMET Optimization |

| Hydration Free Energy (HFE) [28] | HFE | 500 | Varies with model iteration | Binding Affinity Prediction |

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

This table lists key computational tools and datasets that function as essential "reagents" for conducting experiments in this field.

| Item Name | Function / Purpose | Specification / Version |

|---|---|---|

| DeepChem Library [28] | Provides foundational deep learning models (e.g., Graph Neural Networks) for molecular property prediction. | Version compatible with active learning extensions. |

| COVDROP Method [28] | A batch active learning selection method that uses Monte Carlo Dropout to estimate uncertainty and maximize joint entropy for diverse batch selection. | Custom implementation as described in the source. |

| BAIT Method [28] | An alternative batch active learning method that uses Fisher information for sample selection. Useful for comparative benchmarking. | As per Ash et al. (2021). |

| Public ADMET Datasets [28] | Curated data for properties like solubility, lipophilicity, and permeability for model training and validation. | Specific datasets from ChEMBL, Wang et al., Sorkun et al. |

| Simplex Optimization Algorithm [19] | The core routine for navigating the multi-parameter space without needing gradient information. | Custom code implementing Nelder-Mead logic. |

Protocol 1: Setting Up an Integrated Simplex-Active Learning Cycle

This protocol outlines the steps for a single, integrated cycle. The accompanying diagram visualizes this workflow.

Workflow: Integrated Optimization Cycle

- Initialize: Begin with an initial dataset of molecules with measured properties. Define the Simplex parameters (e.g., initial step size, reflection/contraction coefficients) and the Active Learning batch size.

- Model Training: Train a deep learning model (e.g., a Graph Neural Network) on the current dataset to predict the target property (e.g., binding affinity).

- Active Learning Batch Selection: From a large virtual library of candidate molecules, use the COVDROP or COVLAP method to select a diverse and informative batch. This batch is chosen to maximize the reduction in model uncertainty.

- Simplex Optimization: Use the Simplex algorithm to generate and rank new candidate molecules. The predictive model from Step 2 acts as the surrogate "response function" for the Simplex. The Simplex's goal is to find the factor combination (molecular features) that maximizes or minimizes the predicted property.

- Experimentation: Synthesize and test the top candidates identified by the integrated workflow in wet-lab experiments to obtain ground-truth data.

- Data Integration: Add the new experimental results to the training dataset.

- Convergence Check: Evaluate if the stopping criteria (e.g., performance target, maximum cycles, minimal improvement) have been met.

- Iterate: If not converged, return to Step 2 for the next cycle.

Protocol 2: Simplex Optimization of a Two-Factor System

This protocol details the steps of the Simplex method for a simple two-factor system, which forms the core of the optimization engine. The diagram below illustrates the process.

Workflow: Simplex Operations

- Initialization: Start with a simplex of N+1 points. For two factors (F1, F2), this is a triangle. Run experiments to evaluate the response (e.g., binding affinity) at each point [19].

- Ranking: Rank the points from Best (B, highest response) to Worst (W, lowest response).

- Reflection: Calculate the centroid (C) of all points except W. Reflect W through C to generate a new point R. The response at R is evaluated [19].

- Decision Logic:

- If R is better than B, consider Expansion to explore further.

- If R is worse than B but better than N, Accept R and form a new simplex with B, N, R.

- If R is worse than N, perform Contraction to generate a point between C and W or between C and R.

- If the contracted point is not an improvement, Reduce the entire simplex towards B.

- Iteration: Repeat steps 2-4 until the convergence criteria are met [19].

Understanding Sequential Simplex Optimization

Sequential Simplex Optimization is a multivariate method used to find the optimal combination of factor levels that produces the best response in a system. Unlike classical "one-factor-at-a-time" approaches, it efficiently handles multiple interacting variables simultaneously with a relatively small number of experiments [27] [13].

The method works by moving a geometric figure (a simplex) through the experimental factor space. For k factors, the simplex has k+1 vertices. Each vertex represents a unique set of experimental conditions. The algorithm iteratively replaces the worst-performing vertex with a new, reflected one, guiding the simplex toward the optimal region [13].

Key Advantages:

- Efficiency: Finds improved conditions in fewer experiments compared to traditional methods [27].

- Simplicity: Does not require complex mathematical or statistical analysis to guide the experimental process [27] [13].

- Practicality: Ideal for optimizing systems with several continuously variable factors, such as instrument parameters or chemical reaction conditions [13].

A Step-by-Step Experimental Protocol