Sequential Simplex Optimization in Chemistry: A Practical Guide for Modern Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive guide to sequential simplex optimization, a cornerstone multivariate method in chemical research and analytical method development.

Sequential Simplex Optimization in Chemistry: A Practical Guide for Modern Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to sequential simplex optimization, a cornerstone multivariate method in chemical research and analytical method development. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles of the simplex method, contrasting it with gradient-based and modern evolutionary approaches. The content delivers practical strategies for implementation, troubleshooting common pitfalls, and optimizing performance in real-world chemical applications such as chromatography and reaction condition screening. Finally, it offers a rigorous framework for validating simplex performance and comparing it with contemporary optimization algorithms, empowering scientists to make informed methodological choices for their specific experimental challenges.

What is Sequential Simplex Optimization? Core Principles for Chemists

What is the core difference between univariate and multivariate optimization?

Univariate optimization involves changing one factor at a time while holding all others constant. This approach is time-consuming, reagent-intensive, and unable to account for interactions between variables, which means it may fail to identify true optimal conditions [1].

Multivariate optimization simultaneously varies all factors to find the best combination, accounting for interactions between variables and leading to more efficient and effective method development. This approach can achieve the highest efficiency of analytical methods in the shortest time period [1].

The following table summarizes the key differences:

| Characteristic | Univariate Optimization | Multivariate Optimization |

|---|---|---|

| Factor Variation | One factor at a time | All factors simultaneously |

| Interaction Effects | Unable to detect | Can identify and quantify |

| Experimental Efficiency | Low (more experiments) | High (fewer experiments) |

| Reagent & Time Cost | High | Low |

| Probability of Finding True Optimum | Lower | Higher |

When should I use the Simplex method instead of the Gradient method?

The choice between these two sequential optimization methods depends on the nature of your objective function and whether you can calculate its partial derivatives [1].

Use the Gradient Method when: Your function has several variables and you can obtain its partial derivatives. This method, also known as the "steepest-ascent" or "steepest-descent" method, uses the gradient vector which points in the direction of the function's steepest increase [1]. It generally offers better reliability and faster convergence to the optimum when derivatives are available [1].

Use the Simplex Method when: Your function has several variables but you cannot obtain its partial derivatives [1]. This direct search method is based on a geometric figure defined by a number of points equal to N+1, where N is the number of factors to optimize. For two factors, the simplex is a triangle; for three factors, it's a tetrahedron [1] [2].

Why is my optimization solver taking a long time or not converging?

Several common issues can cause convergence problems in optimization algorithms:

Poor scaling: If your problem is not adequately centered and scaled, the solver may fail to converge correctly. Ensure each coordinate has roughly the same effect on the objective, with none having excessively large or small scale near a possible solution [3].

Inappropriate stopping criteria: If your tolerance values (e.g.,

TolFunorTolX) are too small, the solver might fail to recognize it has reached a solution. If too large, it may stop far from an optimal point [3].Poor initial point: The starting point significantly impacts convergence. Try starting your optimization from multiple different initial points, particularly if you suspect local minima [3].

Insufficient iterations: Solver may run out of iterations. Try increasing the maximum function evaluation and iteration limits, or restart the solver from its final point to continue searching [3].

Objective function returns NaN or complex values: Optimization solvers require real-valued objective functions. Complex values or NaN returns can cause unexpected results [3].

What should I do if the solution found is not the global optimum?

There is no guarantee a solution is a global minimum unless your problem is continuous and has only one minimum [3]. To search for a global optimum:

Multiple starting points: Repeat the optimization starting from different initial points. If you find the same optimum from various starting locations, you can have greater confidence it's the global optimum [1] [3].

Evolutionary approach: First solve problems with fewer variables, then use these solutions as starting points for more complex problems through appropriate mapping [3].

Simpler initial stages: Use less stringent stopping criteria and simpler objective functions in initial optimization stages to identify promising regions before refining your search [3].

How can I incorporate constraints into my multivariate optimization problem?

For optimization problems with constraints, several effective methods are available:

Lagrange Multipliers: This method incorporates constraints by adding a multiple of the constraint equation to the objective function, then finding the optimum of the resulting Lagrangian function [4]. The Lagrange multiplier (λ) represents the cost of violating the constraint [4].

Transformation Methods: Modify your objective function to return a large positive value at infeasible points, effectively penalizing constraint violations and steering the solver toward feasible regions [3].

For example, to minimize f(x, y) = x² + y² subject to x + y = 1, the Lagrangian would be: L(x, y, λ) = x² + y² - λ(x + y - 1) You would then solve the system of equations derived from setting all partial derivatives to zero [4].

Experimental Protocol: Sequential Simplex Optimization for HPLC Method Development

Based on a study optimizing an HPLC method for losartan potassium determination [5], here is a detailed protocol for implementing sequential simplex optimization:

Initial Experimental Design

- Identify Critical Factors: Select variables significantly influencing your analytical response. In the HPLC example, these typically include mobile phase composition, pH, flow rate, and column temperature [5].

- Define Initial Simplex: Create a geometric figure with k+1 vertexes, where k equals the number of variables. For two factors, this is a triangle; for three, a tetrahedron [2].

- Set Factor Bounds: Establish reasonable ranges for each factor based on preliminary experiments or literature values.

Response Measurement and Vertex Evaluation

- Run Experiments: Conduct experiments at each vertex of the current simplex.

- Measure Responses: Quantify the analytical response (e.g., chromatographic resolution, peak symmetry, sensitivity) for each experimental condition [5].

- Statistical Validation: Ensure measurements meet precision requirements before proceeding (e.g., RSD < 2.0% for replicate measurements) [5].

Simplex Movement and Reflection

- Identify Performance: Label the vertex with the worst response as "W" and the best as "B" [2].

- Calculate Reflection: Reflect the worst vertex through the centroid of the remaining vertices to generate a new candidate point R using the formula: R = P + α(P - W) where P is the centroid point and α is the reflection coefficient (typically 1.0) [2].

Expansion, Contraction, and Termination

- Evaluate New Vertex: Test the reflected point R experimentally.

- Expansion: If R is better than the current best vertex B, further expand the simplex in this promising direction [2].

- Contraction: If R is worse than previous vertices, contract the simplex toward better-performing regions [2].

- Termination Criteria: Continue iterations until the simplex oscillates around an optimum or response improvement falls below a predetermined threshold [1].

Method Validation

- Final Optimization: Once optimal conditions are identified, validate the method according to ICH guidelines, assessing accuracy, precision, selectivity, robustness, and linearity [5].

- Robustness Testing: Verify method performance under slight variations in optimal conditions to ensure practical applicability [5].

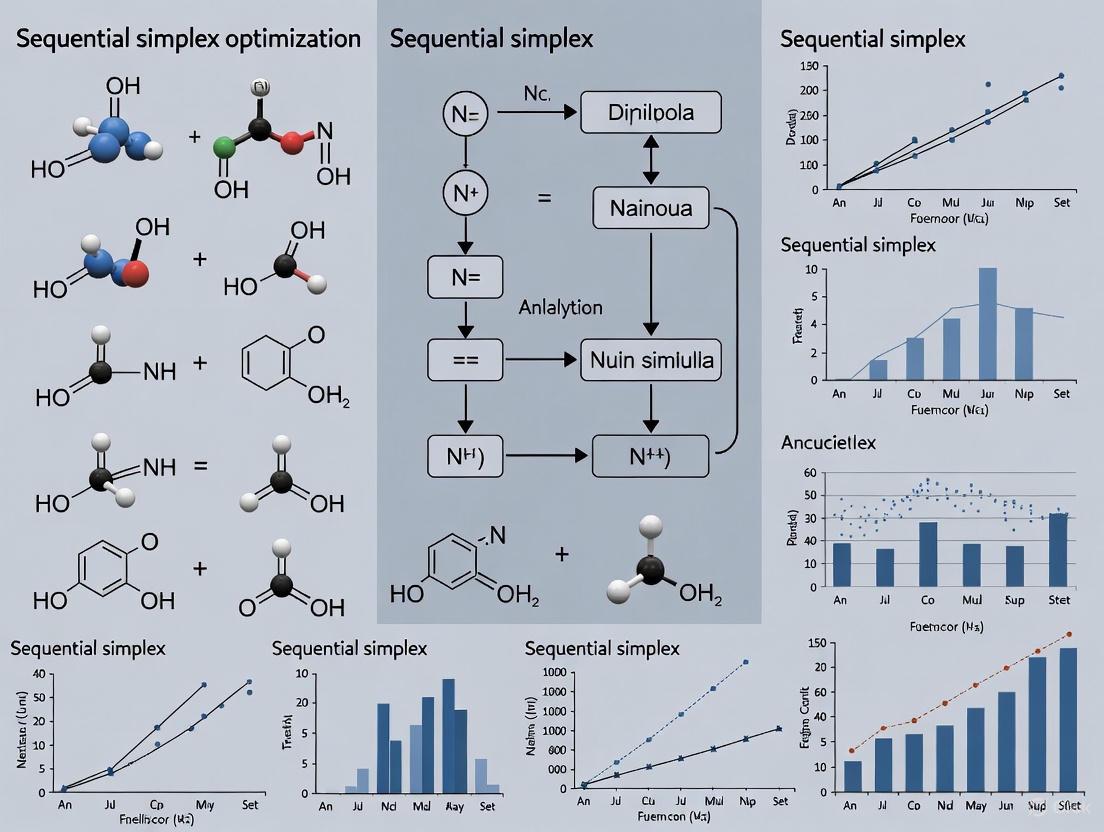

Sequential Simplex Optimization Workflow

Research Reagent Solutions for Multivariate Optimization

The following table details key materials and their functions in multivariate optimization experiments, particularly in pharmaceutical applications:

| Research Reagent | Function in Optimization | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Chemometric Software | Provides algorithms for experimental design, data analysis, and response surface modeling | Simplex optimization, response surface methodology, multivariate data analysis [6] |

| Process Analytical Technology (PAT) | Enables real-time monitoring of critical quality attributes during process optimization | Near-infrared (NIR) spectroscopy, Raman spectroscopy for process understanding [6] |

| Design of Experiments (DoE) | Structured approach for designing experiments to efficiently explore factor relationships | Fractional factorial designs, Doehlert designs, Box-Behnken designs [5] [2] |

| Multivariate Modeling Algorithms | Build predictive models between process parameters and product quality | Partial Least Squares (PLS), Principal Component Analysis (PCA), Artificial Neural Networks (ANN) [6] |

| Quality by Design (QbD) | Systematic approach to development that emphasizes product and process understanding | Defining design space, identifying critical process parameters, establishing control strategies [6] |

How do I handle multiple, conflicting objectives in pharmaceutical optimization?

Many real-world optimization problems involve multiple, often conflicting objectives. In pharmaceutical development, you might need to simultaneously maximize biological activity while optimizing multiple ADMET properties (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, Toxicity) [7].

Multi-Objective Optimization Framework: Define your problem using the standard multi-objective formulation [7]: Minimize f(x) = (f₁(x), ..., fₘ(x))ᵀ Subject to constraints gᵢ(x) ≤ 0 and hⱼ(x) = 0 where x is the potential solution and f₁(x), ..., fₘ(x) are the objectives to be optimized.

Conflict Analysis: Before selecting an optimization method, analyze the conflict relationships between your objectives. When objectives conflict, there may be no single solution that optimizes all objectives simultaneously, but rather a set of Pareto-optimal solutions [7].

Specialized Algorithms: Use multi-objective evolutionary algorithms (MOEAs) such as NSGA-2 or AGE-MOEA, which are particularly effective for high-dimensional optimization problems with multiple conflicting objectives [7].

For anti-breast cancer drug development, researchers have successfully applied multi-objective optimization to balance biological activity (PIC₅₀) with five key ADMET properties, demonstrating the practical value of this approach in pharmaceutical applications [7].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My optimization is stuck, cycling through the same vertices without improving the objective function. What is happening? This is likely cycling, caused by degeneracy where multiple bases represent the same vertex. Implement Bland's Rule: always choose the variable with the smallest index when selecting both the entering and exiting variables to guarantee termination [8].

Q2: The initial solution for my chemical reaction factors is infeasible. How do I start the simplex method? You must first conduct a Phase I analysis [9]. Introduce artificial variables to create a feasible starting point and solve a new auxiliary LP to minimize their sum. Once a feasible solution for the original problem is found, proceed with the standard simplex method (Phase II) [9] [8].

Q3: How do I handle experimental factors (variables) that can be negative in my reaction optimization? The standard simplex method requires non-negative variables. To handle an unrestricted variable ( z1 ), replace it with the difference of two non-negative variables: ( z1 = z1^{+} - z1^{-} ), where ( z1^{+} \geq 0 ) and ( z1^{-} \geq 0 ) [9] [10].

Q4: The algorithm suggests I should move along an unbounded edge. What does this mean for my experiment? An unbounded solution in a practical context like chemistry often indicates a missing constraint [10] [11]. Re-examine your experimental design; there is likely a physical limitation you have not modeled, such as a maximum allowable temperature, pressure, or concentration.

Q5: What is the geometrical interpretation of a pivot operation in factor space? Each pivot operation moves the solution from one vertex (corner point) of the feasible region to an adjacent vertex along an edge, improving the objective function at each step [9] [11] [8]. In a multi-factor space, you are moving from one specific combination of factors to a neighboring, better-performing combination.

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

| Problem | Symptom | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Degenerate Experiment | Objective function does not improve after a pivot; the same solution value is maintained. | Continue pivoting as permitted by Bland's Rule. The algorithm will typically exit the degenerate vertex after a finite number of steps [8]. |

| Numerical Instability | Results are erratic or change significantly with small perturbations in reaction data. | Re-formulate the LP model to avoid poorly scaled constraints. Use software that allows for high-precision computation [8]. |

| Infeasible Formulation | The Phase I procedure cannot find a solution where all constraints are satisfied. | The constraints on your reaction factors may be contradictory. Re-examine the physical limits and requirements you have defined for your system [9]. |

Experimental Protocol: Implementing the Simplex Algorithm for Reaction Optimization

This protocol details the steps to optimize a chemical reaction, such as a catalytic reaction, using the sequential simplex method. The goal is to maximize yield by adjusting factors like temperature, concentration, and pressure.

1. Problem Formulation and Standardization

- Define the Objective: Formally state the goal (e.g., Maximize Yield = ( c1X1 + c2X2 + c3X3 ), where ( X_i ) are factor levels).

- Formulate Constraints: Define all experimental limits as linear inequalities (e.g., ( \text{Temperature} \leq 100^\circ\text{C} ) becomes ( X_1 \leq 100 )) [10].

- Convert to Standard Form:

2. Construct the Initial Simplex Tableau Create the initial matrix (tableau) that represents the linear program. The first row contains the negative coefficients of the objective function, and subsequent rows represent the constraint equations [8].

Initial Tableau Structure:

| Basic | ( X_1 ) | ( X_2 ) | ( X_3 ) | ( S_1 ) | ( S_2 ) | Solution |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ( Z ) | ( -c_1 ) | ( -c_2 ) | ( -c_3 ) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| ( S_1 ) | ( a_{11} ) | ( a_{12} ) | ( a_{13} ) | 1 | 0 | ( b_1 ) |

| ( S_2 ) | ( a_{21} ) | ( a_{22} ) | ( a_{23} ) | 0 | 1 | ( b_2 ) |

3. Iterative Pivoting Procedure Repeat until no more negative values exist in the objective row (for maximization):

- Select Entering Variable: Identify the non-basic variable with the most negative coefficient in the objective row. This variable will enter the basis [8].

- Select Exiting Variable: For the pivot column, compute the ratio of the Solution column to the corresponding positive entries in the pivot column. The basic variable with the smallest non-negative ratio exits the basis [12] [11].

- Perform Pivot Operation: Use row operations to make the pivot element 1 and all other elements in the pivot column 0 [9] [8].

4. Solution Interpretation The final tableau provides the optimal factor levels. The basic variables show the values of the factors at the optimum, and the value of ( Z ) is the maximum achievable yield [11].

Research Reagent & Computational Solutions

| Item Name | Function in Simplex Optimization |

|---|---|

| Slack Variable | Converts a "≤" resource constraint into an equality, representing unused resources [9] [12]. |

| Surplus Variable | Converts a "≥" requirement constraint into an equality, representing excess over the minimum requirement [9]. |

| Artificial Variable | Provides an initial basic feasible solution for Phase I of the simplex algorithm when slack variables are insufficient [9]. |

| Tableau | A matrix representation of the LP problem that is updated during pivoting to track the solution's progress [9] [8]. |

| Bland's Rule | A pivot selection rule that prevents cycling by choosing the variable with the smallest index, ensuring algorithm termination [8]. |

Visualizing the Simplex Walk in 3-Factor Space

The following diagram illustrates the path of the simplex algorithm through a three-dimensional factor space, moving from one vertex to an adjacent one until the optimum is found.

Simplex Algorithm Path in Factor Space

Your FAQs on the Sequential Simplex Method

Q1: What is the fundamental purpose of the reflection, expansion, contraction, and shrinkage operations in the simplex method? These operations are the core mechanics of the Nelder-Mead simplex algorithm, a direct search method used to find a local minimum or maximum of an objective function. They define how the simplex (a geometric shape with n+1 vertices in n dimensions) adapts its shape and position to navigate the parameter space. The algorithm uses these operations to iteratively replace the worst-performing vertex of the simplex, effectively moving the entire simplex towards an optimum without requiring derivative information [13].

Q2: During an experiment, my simplex appears to be stuck in a cycle, not improving the objective function. What is happening and how can I resolve it? This indicates a potential convergence issue. The Nelder-Mead method is a heuristic and can sometimes converge to non-stationary points or struggle with specific function landscapes. To address this:

- Restart the Experiment: A common solution is to re-initialize the simplex, using the current best point as a new starting vertex. This can help the algorithm escape a non-productive region.

- Check Simplex Degeneracy: Ensure that your simplex has not become degenerate (where points are co-linear in 2D or co-planar in 3D). If degeneracy is suspected, re-initialize the simplex around the current best point.

- Review Parameter Scaling: Confirm that all parameters in your chemical system (e.g., temperature, concentration, pH) are on a similar scale. Poorly scaled parameters can distort the simplex and hinder progress.

- Consider a Modified Algorithm: Recent research has proposed variants of the Nelder-Mead method that fix the shape of the simplex to prevent degeneration, which can ensure convergence even for higher-dimensional problems [14].

Q3: How do I know which operation (e.g., Expansion vs. Outside Contraction) to perform in a given iteration? The choice is governed by a set of rules that compare the value of the objective function at the reflected point against the current best, worst, and other vertices. The following workflow outlines the standard decision-making process. While standard parameter values exist (like α=1 for reflection), some modified algorithms compute an optimal value for this parameter at each iteration to accelerate convergence [14] [13].

Q4: My optimization is progressing very slowly in a high-dimensional parameter space (e.g., optimizing 10+ reaction conditions). Is this expected? Yes, this is a known challenge often called the "curse of dimensionality." The convergence performance of the traditional Nelder-Mead method is proportional to the dimension of the problem; lower-dimensional problems converge faster. For complex, high-dimensional optimization problems in drug development (such as optimizing multiple reaction parameters simultaneously), you might consider using a modified simplex method that maintains a fixed, non-degenerate simplex structure or incorporates gradient-based information for faster convergence [14].

Troubleshooting Guide

| Symptom | Potential Cause | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| No improvement over many iterations, objective function value is stagnant. | Simplex has become degenerate or is traversing a flat region of the response surface. | Re-initialize the simplex around the current best vertex. Check for parameter scaling issues. |

| Simplex shrinks repeatedly without converging to an optimum. | The shrinkage operation is being triggered too often, often in a valley or ridge. | Verify the experiment's noise level and increase the convergence tolerance if the experimental error is significant. |

| Oscillation between similar parameter sets. | The algorithm is navigating a poorly conditioned or noisy region near the optimum. | Average the oscillating vertices to find a new center point, or switch to a more robust optimization method. |

| Convergence to a poor local optimum that does not match experimental knowledge. | The initial simplex was placed in the attraction basin of a sub-optimal point. | Restart the optimization from a different, scientifically justified initial guess. |

Experimental Protocol: Sequential Simplex Optimization of a Chemical Reaction

This protocol outlines the steps to optimize a chemical reaction using the Nelder-Mead simplex procedure, based on its application in chromatography and other chemical analyses [15].

1. Define the System and Objective:

- Identify Critical Parameters (Variables): Select the key parameters to optimize (e.g.,

Initial Temperature (T0),Hold Time (t0),Rate of Temperature Change (r)for a chromatography method, orCatalyst Loading,Reaction Temperature, andSolvent Ratiofor a synthesis) [15]. - Formulate the Objective Function: Define a quantitative criterion (Cp) to maximize or minimize. For example, a chromatography optimization might use:

Cp = Nr + (t_R,n - t_max) / t_max, whereNris the number of detected peaks and the second term penalizes long analysis times [15].

2. Initialize the Simplex:

- Start with an initial guess for the first vertex,

x1, based on prior knowledge. - Construct the remaining

nvertices of the simplex by adding a predetermined step size to each parameter in turn. For example:x2 = (x1₁ + δ₁, x1₂, ..., x1_n),x3 = (x1₁, x1₂ + δ₂, ..., x1_n), and so on. This creates a non-degenerate initial simplex [13].

3. Run the Iterative Optimization:

- Step 1: Run Experiments and Evaluate. Perform the experiment (e.g., chromatography run or chemical reaction) for each vertex in the current simplex and calculate the objective function value for each.

- Step 2: Order Vertices. Sort the vertices from best (e.g., highest Cp) to worst (lowest Cp). Label them

x_b(best),x_s(second-worst), andx_w(worst). - Step 3: Calculate Centroid. Calculate the centroid,

x_m, of all vertices except the worst one (x_w). - Step 4: Execute Simplex Operations.

- Reflection: Compute the reflection point

x_r = x_m + α(x_m - x_w), typically with α=1. Evaluatef(x_r)[13]. - Expansion: If

x_ris better thanx_b, compute the expansion pointx_e = x_m + γ(x_r - x_m)with γ=2. Ifx_eis better thanx_r, replacex_wwithx_e; otherwise, usex_r[13]. - Contraction: If

x_ris better thanx_sbut worse thanx_b(outside contraction), tryx_c = x_m + ρ(x_r - x_m)with ρ=0.5. Ifx_ris worse thanx_s(inside contraction), tryx_c = x_m + ρ(x_w - x_m). If the contraction point is better than the worst point, use it [13]. - Shrinkage: If contraction fails, shrink the entire simplex towards the best vertex

x_bby replacing every vertexx_iwithx_b + σ(x_i - x_b), where σ=0.5 [13].

- Reflection: Compute the reflection point

- Step 5: Check Termination Criteria. Repeat from Step 1 until the improvement in the objective function falls below a predefined threshold or a maximum number of iterations is reached.

Research Reagent Solutions & Key Parameters

The table below details the core components involved in setting up a sequential simplex optimization for a chemical process.

| Item / Parameter | Function in the Optimization Process |

|---|---|

| Objective Function (e.g., Cp) | A quantitatively defined criterion that the algorithm aims to maximize or minimize; it mathematically represents the success of an experiment (e.g., peak separation, product yield) [15]. |

| Initial Simplex | The starting set of n+1 experimental conditions (vertices) in an n-parameter space. Its construction is critical as it defines the initial search region [13]. |

| Reflection Parameter (α) | Controls the distance the simplex projects away from the worst point. A value of 1 is standard, but optimal calculation of α can improve convergence [14] [13]. |

| Expansion Parameter (γ) | Allows the simplex to extend further in a promising direction if the reflection point is highly successful. A value of 2 is typically used [13]. |

| Contraction Parameter (ρ) | Reduces the size of the simplex when a reflection is not successful, helping to zero in on an optimum. A value of 0.5 is standard [13]. |

| Shrinkage Parameter (σ) | Governs the reduction of the entire simplex around the best point when all else fails, restarting the search on a finer scale. A value of 0.5 is typical [13]. |

Sequential Simplex Optimization is a practical, multivariate strategy used to improve the performance of a system, process, or product by finding the best combination of experimental variables (factors) to achieve an optimal response [2]. In analytical chemistry, this method is employed to achieve the best possible analytical characteristics, such as better accuracy, higher sensitivity, or lower quantification limits [2]. Unlike univariate optimization (which changes one factor at a time and cannot assess variable interactions), simplex optimization varies all factors simultaneously, providing a more efficient path to the optimum [2] [1]. The method operates by moving a geometric figure (a simplex) through the experimental domain; for k variables, the simplex is defined by k+1 points (e.g., a triangle for two variables) [2]. This guide outlines the core scenarios for applying simplex methods, provides protocols for implementation, and addresses common troubleshooting issues.

Core Scenarios for Selecting the Simplex Method

Ideal Problem Typologies

The simplex method is particularly well-suited for the following situations:

- Optimizing Multiple Variables Simultaneously: It is designed to efficiently handle problems with several factors, making it superior to one-factor-at-a-time approaches [2] [1].

- Systems with Unobtainable Partial Derivatives: The simplex method is a direct search algorithm that does not require calculating derivatives of the objective function. It is therefore the recommended choice when the mathematical model of your system is complex, unknown, or when partial derivatives are difficult or impossible to obtain [1].

- Black-Box or Empirically-Defined Systems: When the relationship between variables and the response is not well-defined by a simple equation, the simplex method can navigate the experimental space based solely on the measured output [16].

- Instrumental Parameter Tuning: It has been successfully applied to optimize parameters for techniques like ICP OES, flow injection analysis, and chromatography [2] [17].

- Automated and Robotic Systems: The characteristics of the simplex method are quite proper for the optimization of automated analytical systems because the algorithm is easily programmable and can run with minimal human intervention [2].

Comparison with Other Optimization Methods

Choosing the right optimization strategy depends on your problem's characteristics. The table below compares simplex to other common methods.

| Method | Best For | Key Advantage | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Simplex Optimization | Functions with unobtainable partial derivatives; Black-box experimental systems [1]. | Does not require complex mathematical-statistical expertise; Easily programmable [2]. | Can converge slowly or get stuck in local optima; Sensitive to initial simplex size [2]. |

| Gradient Method | Functions with several variables and obtainable partial derivatives [1]. | Faster convergence and better reliability when derivatives are available [1]. | Fails when derivatives cannot be calculated [1]. |

| One-Factor-at-a-Time (OFAT) | Simple, quick initial explorations. | Simple to implement and understand [16]. | Ignores variable interactions; can miss the true optimum; inefficient [16]. |

| Bayesian Optimization | Complex, high-cost optimization problems; global optimization [16]. | Sample-efficient; balances exploration and exploitation; good for global optima [16]. | Can be computationally intensive; more complex to implement. |

| Design of Experiments (DoE) | Systematically modeling multi-parameter interactions; building response surfaces [16]. | Explicitly accounts for variable relationships [16]. | Typically requires more data upfront, increasing experimental cost [16]. |

The following workflow can help you decide if the simplex method is appropriate for your experimental needs:

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Standard Operating Procedure: Modified Simplex Optimization

The Modified Simplex method, proposed by Nelder and Mead, improves upon the basic simplex by allowing the geometric figure to expand and contract, leading to a faster and more robust convergence [2].

Step-by-Step Protocol:

Define the System:

- Identify the Response (Y): The measurable output you wish to optimize (e.g., yield, sensitivity, peak resolution).

- Identify the Variables (k): The key factors you can control (e.g., temperature, pH, concentration). Let

kbe the number of variables.

Initialize the Simplex:

- Construct an initial simplex with k+1 experiments (vertices).

- For example, with 2 variables (X1, X2), the simplex is a triangle defined by 3 points:

(X1₁, X2₁),(X1₂, X2₂),(X1₃, X2₃)[2]. - The size of the initial simplex is crucial. Use your experience or preliminary data to choose a size that is large enough to progress efficiently but not so large that it misses detail [2].

Run Experiments and Rank Vertices:

- Perform the experiments at the initial simplex points and measure the response (Y) for each.

- Rank the vertices from Best (B) to Worst (W). For a maximization problem, the point with the highest Y is B; for minimization, the lowest is B.

Iterate the Simplex Algorithm:

- Calculate the Centroid (P₀): Calculate the average of all points except W.

- Reflection: Calculate the Reflected Point (Pᵣ) using

Pᵣ = P₀ + α(P₀ - W), where the reflection coefficient α is typically 1 [2]. Run the experiment at Pᵣ.- If the response at Pᵣ is better than W but not better than B, accept Pᵣ and form a new simplex by replacing W with Pᵣ.

- Expansion: If Pᵣ is better than B, calculate the Expanded Point (Pₑ) using

Pₑ = P₀ + γ(Pᵣ - P₀), where the expansion coefficient γ is typically 2 [2]. Run the experiment at Pₑ.- If Pₑ is better than Pᵣ, accept Pₑ into the new simplex. Otherwise, accept Pᵣ.

- Contraction: If Pᵣ is worse than W (or the second-worst point), the simplex is likely too large and needs to contract.

- Calculate the Contracted Point (P꜀) using

P꜀ = P₀ + ρ(W - P₀), where the contraction coefficient ρ is typically 0.5 [2]. Run the experiment at P꜀. - If P꜀ is better than W, accept P꜀ into the new simplex.

- Calculate the Contracted Point (P꜀) using

- Multiple Contraction: If P꜀ is not better than W, a multiple contraction around the current best point (B) is performed. All other vertices are moved halfway towards B [2].

Termination:

- Repeat Step 4 until the simplex converges on the optimum or a predetermined termination criterion is met. Common criteria include:

- The difference in response between the best and worst vertices falls below a set threshold.

- The simplex size becomes smaller than a defined value.

- A maximum number of iterations is reached.

- Repeat Step 4 until the simplex converges on the optimum or a predetermined termination criterion is met. Common criteria include:

The logic of a single iteration in the Modified Simplex algorithm is summarized below:

Key Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details common materials and their functions in experiments optimized via simplex methods, particularly in analytical chemistry.

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experiment | Example Context |

|---|---|---|

| Pyrogallol Red | Chromogenic agent; forms a colored complex with analytes for detection [17]. | Spectrophotometric determination of periodate and iodate [17]. |

| Immobilized Ferron | Solid-phase sorbent for online preconcentration of metal ions [17]. | Flow Injection-AAS determination of iron [17]. |

| Micellar Solutions | Ordered assemblies of surfactants that can stabilize phosphorescence or act as a mobile phase in chromatography [17]. | Micellar-stabilized room temperature phosphorescence; Micellar liquid chromatography [17]. |

| Solid-Phase Microextraction (SPME) Fiber | A fiber coating that extracts and pre-concentrates analytes from samples directly into analytical instruments [17]. | GC-MS determination of PAHs, PCBs, and phthalates [17]. |

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

FAQ 1: My simplex oscillations and does not converge to a single point. What should I do?

- Problem: This is often caused by a simplex that is too large, causing it to overshoot the optimum repeatedly [2].

- Solution: Implement a size reduction rule. If the contraction point is not successful, perform a multiple contraction, moving all vertices halfway towards the current best vertex. This shrinks the simplex and allows for a finer search in the most promising region [2].

FAQ 2: The algorithm seems to have gotten stuck in a local optimum, not the best overall conditions. How can I escape?

- Problem: The simplex method can converge to local optima, especially in a complex response surface.

- Solution: Restart the optimization from a different initial simplex. This is a standard practice to verify that you have found the global optimum and not a local one [1]. Alternatively, consider hybrid approaches that combine the simplex method with other global optimization techniques to broaden the search [2] [16].

FAQ 3: How do I handle optimization when my response is influenced by noise or experimental error?

- Problem: Experimental noise can cause the ranking of vertices to be unreliable, leading the simplex in the wrong direction.

- Solution: Replicate experiments at the vertices, particularly when responses are close. Using the average response for ranking can improve robustness. Furthermore, newer trends involve using multi-objective optimization or hybrid methods that are more robust to noise [2] [16].

FAQ 4: I need to optimize for multiple responses simultaneously (e.g., high yield and low cost). Can simplex handle this?

- Problem: The standard simplex is designed for a single objective.

- Solution: Use a Multi-Objective Simplex Optimization approach. This often involves combining the multiple responses into a single objective function, for example, by using a Desirability Function, which transforms each response into a desirability value between 0 and 1, and then optimizes the overall composite desirability [17].

Sequential Simplex Optimization (SSO) is an evolutionary operation (EVOP) technique used to optimize a system response by efficiently adjusting several experimental factors simultaneously. In chemistry, it is applied to find the best combination of factor levels—such as temperature, concentration, or pH—to achieve an optimal outcome like maximum yield, sensitivity, or purity [18]. Unlike "classical" optimization methods that first screen for important factors and then model the system, SSO inverts this process: it first finds the optimum combination of factor levels and then models the system in that region [18]. The method is driven by a logical algorithm rather than complex statistical analysis, making it efficient for optimizing a relatively large number of factors in a small number of experiments [18].

Core Concepts: The Simplex Algorithm

The Basic Principle

For an optimization involving k factors, a simplex is a geometric figure defined by k+1 vertices. In two dimensions (two factors), this figure is a triangle; in three dimensions, it is a tetrahedron [19]. This geometric figure moves through the experimental factor space based on a set of rules, rejecting the worst-performing vertex at each step and replacing it with a new, better one. This process continues iteratively until the optimum response is reached [19] [2].

Key Rules for Fixed-Size Simplex Movement

The basic (fixed-size) simplex algorithm operates using four primary rules [19]:

- Rule 1: Rank the vertices. Evaluate the response (e.g., product yield) at each vertex of the current simplex. Rank them from best (

v_b) to worst (v_w). - Rule 2: Reflect the worst vertex. Reject the worst vertex and replace it with its reflection through the centroid (midpoint) of the remaining vertices. The factor levels for the new vertex (

v_n) are calculated as:a_{v_n} = 2 * ( (a_{v_b} + a_{v_s}) / 2 ) - a_{v_w}b_{v_n} = 2 * ( (b_{v_b} + b_{v_s}) / 2 ) - b_{v_w}(for a two-factor optimization, wherev_sis the third vertex) - Rule 3: Handle a new worst response. If the new vertex gives the worst response, do not return to the previous worst vertex. Instead, reject the vertex with the second worst response and calculate a new vertex using Rule 2.

- Rule 4: Address boundary conditions. If the new vertex exceeds a physical or practical boundary (e.g., a concentration limit), assign it the worst response and follow Rule 3.

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow of the simplex optimization procedure.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Terms & Reagents

The following table details key concepts and parameters essential for designing and executing a simplex optimization experiment.

| Term/Component | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| Factors (Variables) | The independent variables being adjusted (e.g., temperature, pH, reactant concentration) [18]. |

| Response | The dependent variable being measured and optimized (e.g., product yield, analytical sensitivity, purity) [18]. |

| Vertex | A specific set of factor levels (an experimental condition) within the simplex [19]. |

| Simplex | The geometric figure formed by the vertices (e.g., a triangle for 2 factors) [19]. |

| Reflection | The primary operation of generating a new vertex by reflecting the worst vertex through the centroid of the others [19]. |

Step Size (s_a, s_b) |

The initial step size chosen for each factor, which determines the size of the initial simplex [19]. |

| Boundary Conditions | User-defined limits on factor levels to ensure experimental feasibility and safety (e.g., pH range, max temperature) [19]. |

Experimental Protocol: A Representative Example

This protocol outlines the steps to optimize a simulated chemical response using a two-factor fixed-size simplex, based on a classic example from analytical chemistry literature [19].

Objective

Find the optimum for the response surface described by:

R = 5.5 + 1.5A + 0.6B - 0.15A² - 0.0254B² - 0.0857AB

where A and B are the two factors to be optimized [19].

Initial Setup and First Simplex

Define Initial Factor Levels and Step Sizes:

- Let the initial vertex be

(a, b) = (0, 0). - Set step sizes

s_a = 1.00ands_b = 1.00[19].

- Let the initial vertex be

Calculate Initial Simplex Vertices:

- Vertex 1:

(a, b) = (0, 0) - Vertex 2:

(a + s_a, b) = (1.00, 0) - Vertex 3:

(a + 0.5s_a, b + 0.87s_b) = (0.50, 0.87)[19]

- Vertex 1:

Run Experiments and Record Responses:

- Conduct one experiment at each vertex and measure the response

R. - The initial responses from the example are shown in the table below.

- Conduct one experiment at each vertex and measure the response

Table: Initial Simplex Vertices and Responses

| Vertex | Factor A | Factor B | Response (R) |

|---|---|---|---|

| v1 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 5.50 |

| v2 | 1.00 | 0.00 | To be calculated |

| v3 | 0.50 | 0.87 | To be calculated |

Iterative Optimization Procedure

- Rank the vertices from the best (highest R) to the worst (lowest R).

- Reflect the worst vertex: Calculate the new vertex

v_nusing Rule 2. For a 2-factor simplex, the formulas are:a_{v_n} = 2 * ( (a_{v_b} + a_{v_s}) / 2 ) - a_{v_w}b_{v_n} = 2 * ( (b_{v_b} + b_{v_s}) / 2 ) - b_{v_w}

- Run the experiment at the new vertex

v_nand measure its response. - Apply Rules 3 and 4 if the new vertex is the worst or exceeds a boundary.

- Form a new simplex by replacing

v_wwithv_n. - Repeat the process until the simplex converges around the optimum (i.e., repeated reflections circle around the same region with no significant improvement in response).

The workflow for this specific mathematical example is visualized below.

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

FAQ 1: Why does my simplex appear to be stuck, oscillating between the same points instead of converging on an optimum?

- Possible Cause #1: The simplex is straddling a ridge on the response surface. The reflection rule causes it to bounce back and forth across the ridge.

- Solution: This is a known limitation of the basic fixed-size simplex. Consider switching to a modified simplex algorithm (e.g., Nelder-Mead), which allows the simplex to change size by expanding in a promising direction or contracting to narrow in on an optimum [2].

- Possible Cause #2: The initial step size is too large. The simplex is jumping over the optimum.

- Solution: Restart the optimization with a smaller initial step size to conduct a more localized, fine-tuning search around the suspected optimum region [2].

FAQ 2: What should I do if my calculated new vertex requires a factor level that is outside a safe or practical operating range (e.g., a pH outside the stable range of my catalyst)?

- Solution: This is directly addressed by Rule 4 of the basic algorithm. Assign a deliberately poor response value (e.g., a yield of zero) to this out-of-bounds vertex. The algorithm will then treat it as the worst vertex and follow Rule 3 on the next iteration, reflecting the second-worst vertex instead. This allows the simplex to move away from the impractical boundary and back into the feasible experimental space [19].

FAQ 3: When should I use sequential simplex optimization instead of a classical approach like Response Surface Methodology (RSM) with Design of Experiments (DoE)?

- Answer: The choice depends on your goal.

- Use SSO when your primary goal is to quickly and efficiently find improved conditions or a local optimum without the need for an extensive initial screening or a detailed model. It is highly efficient for moving a system to an "acceptable" performance threshold with few experiments and is excellent for "fine-tuning" a process [18].

- Use Classical RSM/DoE when you need to build a comprehensive mathematical model of the system to understand the precise relationship and interactions between all factors. This is valuable for fundamental process understanding but typically requires more experiments upfront [20] [18].

FAQ 4: A major criticism is that the simplex can get trapped in a local optimum and miss the global optimum. How can I mitigate this risk?

- Solution: The sequential simplex is excellent at finding a local optimum but is not a global search algorithm. To mitigate this:

- Start from different initial vertices. Run the optimization multiple times from different, widely spaced starting points. If all paths converge to the same optimum, you can be more confident in the result.

- Use a hybrid approach. First, use a broader screening technique (like a Plackett-Burman design) or a global optimization method to identify the general region of the global optimum. Then, use the simplex method to "fine-tune" the factor levels within that promising region [18].

Implementing the Simplex Method: A Step-by-Step Guide for Chemical Applications

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What is the first step in initiating a sequential simplex optimization? The first step involves selecting the key factors (independent variables) you wish to optimize and identifying a single, measurable response (dependent variable) that accurately reflects your system's performance [18]. It is critical to define the boundaries for each factor, establishing the minimum and maximum levels you are willing to test [21].

Q2: How many experiments are required for the initial simplex? The number of initial experiments is always one more than the number of factors you are optimizing. For example, if you are optimizing two factors (e.g., temperature and pH), your initial simplex will be a triangle requiring three experiments. For three factors, it would be a tetrahedron requiring four initial experiments, and so on [22].

Q3: What are common pitfalls when selecting a response? A common mistake is choosing a response that is not sufficiently sensitive to the factors being changed, or one that is difficult to measure reproducibly [21] [18]. The response should be a quantitative measure that changes reliably as factor levels are adjusted.

Q4: What should I do if my initial experiments yield a very poor response? This is a common concern. The simplex method is designed to move away from poor performance. As long as your initial simplex is feasible (i.e., all factor combinations are physically possible and safe to run), the sequential rules will quickly guide the simplex toward improved conditions after the first few steps [22] [18].

Troubleshooting Guide

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| No improvement after reflection | The response surface may be complex, or the simplex is moving along a ridge. | The algorithm will typically correct itself by contracting and changing direction. Ensure you are correctly applying the rules for contraction [21]. |

| Simplex is stuck oscillating between two points | This can occur if the simplex encounters a boundary or if the optimum has been nearly reached. | Apply the standard rule to reject the vertex with the second-worst response instead of the worst to change direction [22]. |

| High variability in response measurements | Excessive experimental noise can confuse the simplex algorithm and lead it in the wrong direction. | Improve the precision of your response measurement. If noise is unavoidable, consider replicating experiments at the vertices to obtain an average response [21]. |

| The simplex suggests an experiment outside feasible boundaries | The reflection step calculated a factor level that is unsafe or impossible to set. | Manually adjust the new vertex to the boundary limit. Some modified procedures have specific rules for dealing with boundary constraints [21]. |

Experimental Protocol: Constructing the Initial Simplex

This protocol outlines the methodology for setting up a two-factor sequential simplex optimization, which forms the foundation for all simplex procedures [22].

1. Define the System

- Factors: Clearly identify your independent variables (e.g., Reaction Temperature, Catalyst Concentration).

- Response: Define a single, quantifiable dependent variable to maximize or minimize (e.g., Product Yield, %).

- Bounds: Establish the operational range for each factor.

2. Establish the Initial Simplex For a two-factor system, the initial simplex is a right triangle. The first vertex (Vertex 1) is your best initial guess or current operating conditions.

- Step 1: Run the experiment at Vertex 1 (V1) and record the response.

- Step 2: Calculate the coordinates for Vertex 2 (V2) and Vertex 3 (V3) based on a predetermined step size. A common approach is to set V2 by adding the step size to Factor 1, and V3 by adding the step size to Factor 2 [22].

- Step 3: Run the experiments at V2 and V3 and record their responses.

The workflow for this setup is summarized in the following diagram:

3. Rank Vertices and Proceed After completing the initial experiments, rank the vertices based on the response:

- B (Best): The vertex with the most desirable response.

- N (Next-to-worst): The vertex with the median response.

- W (Worst): The vertex with the least desirable response [22]. This ranking is used to perform the first reflection and generate the next simplex in the sequence.

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key components involved in setting up and running a simplex optimization, treating the methodology itself as the experimental system.

| Item | Function in Simplex Optimization |

|---|---|

| Factors (Independent Variables) | The process parameters or chemical variables being adjusted (e.g., temperature, pH, concentration) to find their optimal levels [18]. |

| Measured Response | The quantitative output of the system (e.g., yield, purity, signal intensity) that is used to evaluate the performance at each vertex [18]. |

| Step Size | A predetermined value that determines the initial size of the simplex and how far new vertices are from the centroid. It balances the speed of movement with the resolution of the search [22] [21]. |

| Factor Boundaries | The predefined minimum and maximum allowable values for each factor, ensuring all experiments are feasible and safe to conduct [21]. |

| Experimental Domain | The multi-dimensional space defined by the upper and lower bounds of all factors, within which the simplex is constrained to move [22]. |

Quantitative Data for a Two-Factor Simplex

The table below exemplifies how the initial simplex coordinates and resulting response data might be structured.

| Vertex | Factor 1: Temperature (°C) | Factor 2: Catalyst (mol%) | Response: Yield (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| V1 | 50 | 1.0 | 65 |

| V2 | 60 | 1.0 | 78 |

| V3 | 50 | 1.5 | 71 |

In this example, V2 (Best), V3 (Next-to-worst), and V1 (Worst) would be ranked to determine the next step.

What is the sequential simplex method in the context of chemical research? The sequential simplex method is a parameter optimization algorithm that guides experimenters toward optimal conditions by evaluating responses at the vertices of a geometric figure (a simplex) and iteratively moving away from poor results. In chemical research, this replaces inefficient "one-variable-at-a-time" approaches, allowing synchronous optimization of multiple reaction variables like temperature, concentration, and time with minimal human intervention [23]. The method operates on the fundamental principle that by comparing the objective function values at the vertices of the simplex, a direction of improvement can be identified, leading the experimenter toward optimal conditions without requiring gradient calculations [24] [25].

Core Concepts and Terminology

What is a simplex and how is it used? A simplex is a geometric figure with one more vertex than the number of dimensions in the optimization problem. For two variables, it is a triangle; for three variables, a tetrahedron, and so on. Each vertex represents a specific combination of experimental parameters, and its associated response value is measured in the laboratory [24]. The simplex method works by comparing these response values and moving the simplex toward more favorable regions of the response surface through reflection, expansion, and contraction operations.

What are the key moves in the simplex procedure? The basic simplex method employs three primary moves to navigate the experimental space [24]:

- Reflection: Moving away from the worst-performing vertex by reflecting it through the centroid of the remaining vertices.

- Expansion: Extending further in a promising direction if the reflected vertex shows significant improvement.

- Contraction: Reducing step size when reflection does not yield improvement, helping to fine-tune the search.

Table 1: Key Moves in the Sequential Simplex Procedure

| Move Type | Mathematical Operation | When Applied | Effect on Search |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reflection | Project worst vertex through centroid of opposite face | Standard procedure after ranking vertices | Moves simplex away from poor regions |

| Expansion | Extend beyond reflection point | Reflection point is much better than current best | Accelerates progress in promising directions |

| Contraction | Move backward toward centroid | Reflection point offers little or no improvement | Refines search and prevents overshooting |

| Multiple Expansions | Repeated expansion in same direction | Consistently improving direction found | Increases speed but requires degeneracy control |

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Why is my simplex becoming degenerate and how can I fix it? Degeneracy occurs when the simplex becomes excessively flat or elongated, losing its geometric properties and hindering progress. This is often caused by repeated expansions in a single direction or multiple failed contractions [24]. To address this:

- Implement angle constraints within the simplex to maintain proper shape

- Apply translation procedures to reset the simplex when degeneracy is detected

- Use the type B method combined with degeneracy constraints, which has proven more reliable in finding optimum regions [24]

- Perform degeneracy calculations only when the worst vertex has been successfully replaced, improving computational efficiency [24]

Why does my simplex fail to converge to the true optimum? False convergence can result from several experimental and methodological issues [24]:

- Static simplex size: The basic simplex method maintains fixed step sizes, preventing refinement near optima. The modified simplex method (MSM) allows the simplex to adjust its size and shape to the response surface.

- Boundary violations: Experimental constraints often limit parameter ranges. When the simplex moves outside feasible boundaries, implement a correction procedure that moves the vertex back to the boundary rather than assigning it an artificially poor response value.

- Noisy response measurements: Chemical experiments often exhibit variability. The extended simplex method in optiSLang can handle solver noise and even failed designs through a penalty approach [25].

How do I handle experimental constraints and boundaries? Chemical optimization often involves parameters with practical limitations (e.g., temperature ranges, concentration limits). When a vertex falls outside feasible boundaries [24]:

- Avoid the traditional approach of assigning an artificially unfavorable response value

- Implement boundary correction by projecting the vertex back to the feasible region

- This approach increases both the speed and reliability of convergence, particularly for optima located on or near variable boundaries

Table 2: Troubleshooting Common Simplex Optimization Issues

| Problem | Symptoms | Solution Approaches | Prevention Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| Degeneracy | Simplex becomes elongated or flat; slow progress | Translation procedures; Angle constraints; Type B method with degeneracy control | Regular shape checks; Constraint on repetitive expansions |

| Boundary Violation | Vertices suggest impossible experimental conditions | Correct vertex back to boundary rather than penalizing | Define feasible parameter ranges before optimization |

| False Convergence | Simplex cycles between similar points without improvement | Implement failed contraction handling; Use modified simplex method | Allow size adjustment; Combine with other optimization methods |

| Noisy Responses | Inconsistent performance at similar parameter sets | Use penalty approaches; Replicate measurements; Filter noise | Improve experimental control; Use robust optimization algorithms |

Advanced Methodologies and Recent Improvements

What are the Type A and Type B modified simplex methods? The modified simplex method (MSM) represents a significant improvement over the basic simplex method (BSM) by allowing the simplex to dynamically adjust its size and shape to the response surface [24]. Two prominent variations have been developed:

Type A Method: Combines standard MSM with reflection from the next-to-worst vertex and compares the response of the expansion vertex with the reflection vertex rather than the previous best vertex. This allows searching in directions other than the direction of the first failed contraction [24].

Type B Method: Handles expansion and contractions after encountering the first failed contraction differently than Type A. Research indicates that Type B combined with translation of repeated failed contracted simplex and a constraint on degeneracy provides a more reliable approach for finding optimum regions [24].

How can I improve the speed of simplex optimization? Several strategies can increase the convergence speed of simplex optimization [24]:

- Utilize an expansion coefficient between 2.2-2.5 rather than the standard value of 2.0

- Implement controlled repetitive expansion in favorable directions with constraints on both degeneracy and response improvement

- Apply a reflection coefficient of 1.0 and contraction coefficient of 0.5, which have been shown to be nearly optimal for many functions

- Perform degeneracy calculations only when necessary to reduce computational overhead

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is the difference between the simplex algorithm and the downhill simplex method? The simplex algorithm (Dantzig's method) is designed specifically for linear programming problems, operating on linear constraints and objectives [9]. In contrast, the downhill simplex method (Nelder-Mead method) is a non-linear optimization heuristic used for experimental optimization in fields like chemistry, where the response surface may not be linear [25]. The downhill simplex uses a geometric simplex that evolves based on experimental responses, making it suitable for laboratory applications.

How many experiments are typically required for simplex optimization? The number of experiments depends on the number of variables and complexity of the response surface. Generally, the initial simplex requires k+1 experiments for k variables. Each iteration typically requires 1-3 new experiments depending on whether reflection, expansion, or contraction is performed. Research suggests that implementing efficiency improvements can significantly reduce the average number of evaluations required for convergence [24].

When should I terminate a simplex optimization? Convergence should be tested when [25]:

- The simplex becomes sufficiently small (parameter convergence)

- The difference in objective function values between vertices falls below a predetermined tolerance

- The maximum number of iterations has been reached

- In chemical applications, practical considerations such as material availability or time constraints may also dictate termination

Can simplex methods handle constrained optimization in chemical experiments? Yes, modern implementations use penalty approaches to handle constraints [25]. For example, the simplex method in optiSLang can manage constraint optimization by penalizing infeasible designs, making it suitable for chemical experiments with practical limitations on parameters.

Experimental Protocols and Implementation

Standard Protocol for Initializing a Simplex Optimization

- Define optimization goal: Clearly specify the objective function (e.g., yield, purity, cost) and determine whether to maximize or minimize.

- Select process variables: Identify key factors (temperature, pH, concentration, etc.) that influence the response.

- Establish feasible ranges: Define minimum and maximum values for each variable based on experimental constraints.

- Choose initial step sizes: Determine appropriate step sizes for each variable, considering the sensitivity of the response.

- Construct initial simplex: Generate k+1 initial experiments where k is the number of variables, ensuring the simplex has non-zero volume.

- Execute experiments: Perform the initial set of experiments in randomized order to minimize systematic error.

- Rank vertices: Order vertices from best (B) to worst (W) based on response values.

Workflow for a Single Simplex Iteration The following diagram illustrates the logical decision process during one complete iteration of the modified simplex method:

Procedure for Handling Boundary Constraints When a vertex falls outside feasible experimental boundaries [24]:

- Identify which parameter(s) exceed their defined limits

- Calculate the correction factor needed to move the vertex to the boundary

- Adjust all parameters of the vertex proportionally to bring it to the feasible region

- Evaluate the response at this corrected boundary position

- Continue with the standard simplex procedure using this corrected value

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Simplex Optimization

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Modified Simplex Algorithm (Type B) | Core optimization engine with adaptive step size | General chemical reaction optimization |

| Degeneracy Constraint Module | Prevents simplex collapse and maintains geometry | Complex multi-parameter optimization problems |

| Boundary Handling Procedure | Corrects vertices to feasible experimental regions | Constrained optimization with practical limits |

| Convergence Test Module | Determines when optimal conditions are reached | All optimization campaigns |

| Response Surface Mapping | Visualizes relationship between parameters and outcomes | Interpretation and validation of results |

Table 4: Performance Comparison of Simplex Method Variations

| Method | Average Evaluations | Non-Converging Runs (%) | Critical Failures (%) | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basic Simplex (BSM) | 125.3 | 15.2 | 8.7 | Simple, well-behaved systems |

| Modified Simplex (MSM) | 98.7 | 9.8 | 4.3 | Most standard chemical optimizations |

| Type A with Degeneracy Control | 87.4 | 6.1 | 2.2 | Noisy response surfaces |

| Type B with Translation | 76.9 | 3.5 | 0.9 | Complex, constrained problems |

| Super Modified Simplex | 82.1 | 4.8 | 1.7 | High-precision applications |

In chromatographic method development, researchers traditionally follow a "classical" approach: first, they run screening experiments to find important factors, then model how these factors affect the system, and finally determine optimum levels [18]. However, when the primary goal is optimization, an alternative strategy using sequential simplex optimization often proves more efficient [18]. This approach reverses the traditional sequence: it first finds the optimum combination of factor levels, then models how factors affect the system in the region of the optimum, and finally screens for important factors affecting the optimized process [18].

The sequential simplex method is an evolutionary operation (EVOP) technique that can optimize several factors simultaneously without requiring detailed mathematical or statistical analysis after each experiment [18]. For continuously variable factors in chemical systems, this method has proven highly efficient, often delivering improved response after only a few experiments [18]. This guide demonstrates how to implement sequential simplex optimization for chromatographic condition optimization while addressing common troubleshooting challenges.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common HPLC Optimization Issues

Retention Time Problems

| Problem Phenomenon | Possible Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Retention Time Drift/Increasing Retention | Poor temperature control [26], Decreasing flow rate due to leaks or pump issues [27], Incorrect mobile phase composition [26], Poor column equilibration [26] | Use a thermostat column oven [26], Check for system leaks and repair [27] [26], Prepare fresh mobile phase and verify composition [26], Increase column equilibration time [26] |

| Retention Time Decreasing | Loss of stationary phase from harsh pH conditions [27], Mass overload of analyte [27], Volume overload from sample solvent [27], Stationary phase dewetting with highly aqueous mobile phases [27] | Adjust mobile phase to less acidic pH [27], Reduce sample concentration or injection volume [27] [28], Ensure sample solvent matches mobile phase composition [27], Flush column with organic-rich solvent or use more hydrophilic stationary phase [27] |

Peak Shape Abnormalities

| Problem Phenomenon | Possible Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Peak Tailing | Secondary interactions with residual silanol groups [28], Column overloading [28] [26], Column contamination [26], Inadequate mobile phase pH [26] | Switch to end-capped columns [28], Work at pH<3 to protonate silanol groups (if column allows) [28], Reduce injection volume or sample concentration [28] [26], Use mobile phase additives like triethylamine [28] |

| Peak Fronting | Sample overloading [28] [26], Solvent effect (sample solvent stronger than mobile phase) [28] | Reduce injection volume [28] [26], Ensure sample solubility in mobile phase [28], Dilute sample or dissolve in mobile phase [26] |

| Broad Peaks | Mobile phase composition change [26], Low flow rate [26], Column temperature too low [26], Column contamination [26] | Prepare fresh mobile phase [26], Increase flow rate [26], Increase column temperature [26], Replace guard column/column [26] |

Baseline and Pressure Issues

| Problem Phenomenon | Possible Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Baseline Noise or Drift | Contaminated mobile phase [28] [26], Air bubbles in system [28] [26], Detector instability [28], Leaks in pump or injector [28] | Use high-purity solvents and degas mobile phase [28] [26], Flush system to remove air bubbles [26], Perform detector maintenance and calibration [28], Inspect system for leaks and replace worn seals [28] [26] |

| Pressure Fluctuations/High Pressure | Clogged filters or column [28] [26], Mobile phase precipitation [26], Flow rate too high [26], Column temperature too low [26] | Replace and clean filters [28], Backflush column or replace [28] [26], Flush system with strong solvent [26], Reduce flow rate [26], Increase column temperature [26] |

Sequential Simplex Optimization: Experimental Protocol

The sequential simplex method follows an iterative process where experimental results directly guide the selection of subsequent conditions. The workflow below illustrates this optimization process:

Implementation Steps

Step 1: Define Variable Space and Response Metric

- Select critical factors to optimize (e.g., %organic solvent, pH, temperature)

- Define feasible ranges for each factor based on column and instrument specifications

- Establish a single response metric to maximize (e.g., resolution, peak capacity, or signal-to-noise)

Step 2: Establish Initial Simplex

- For k factors, run k+1 initial experiments to form the starting simplex

- Ensure initial vertices span a diverse region of the experimental space

- Record response values for each experimental condition

Step 3: Iterate Toward Optimum

- Identify the vertex with the worst response and reflect it through the centroid of the remaining vertices

- Run the new experiment and evaluate its response

- Continue reflecting the worst vertex until no further improvement occurs

- Apply expansion or contraction rules as needed to navigate the response surface efficiently [18]

Step 4: Verify and Model the Optimum

- Once the optimum region is identified, run confirmation experiments

- Use classical experimental designs (e.g., central composite) to model the response surface near the optimum [18]

- Establish control strategies for maintaining optimal performance

Research Reagent Solutions for Chromatographic Optimization

| Reagent/Category | Function in Optimization | Practical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Organic Solvents(Acetonitrile, Methanol) | Modulate retention and selectivity in reversed-phase chromatography [29] | Acetonitrile offers lower viscosity; methanol is cost-effective. Choose based on analyte solubility and UV cutoff [29]. |

| Aqueous Buffers(Phosphate, Acetate, Formate) | Control pH and ionic strength to manipulate analyte ionization and retention [29] | Phosphate buffers are common for HPLC; formate/acetate are MS-compatible. Maintain pH within column specifications (typically 2-8) [29]. |

| Ion-Pairing Agents(TFA, HFBA) | Improve retention and peak shape for ionic analytes [29] | Useful for acidic/basic compounds but may suppress MS signal. Use at low concentrations (0.05-0.1%) [29]. |

| Stationary Phases(C18, C8, Phenyl, Cyano) | Provide the chromatographic surface governing separation mechanism | C18 for most applications; more polar phases (CN, C1) for highly aqueous conditions [27]. End-capped phases reduce peak tailing [28]. |

FAQs on Chromatographic Optimization

Q1: How does sequential simplex optimization compare to traditional One-Variable-at-a-Time (OVAT) approaches?

Sequential simplex is a multidimensional approach that optimizes all factors simultaneously, making it considerably more efficient than OVAT. It can explain interactions between parameters and typically requires fewer experiments, saving both time and reagents [30]. While OVAT is simpler to implement, it may miss optimal conditions resulting from factor interactions.

Q2: What are the limitations of sequential simplex optimization?

The sequential simplex method generally operates well in the region of a local optimum but may not always find the global optimum, particularly in systems with multiple optima [18]. It works best for continuously variable factors and may struggle with categorical variables. For complex systems, a hybrid approach using classical methods to identify the general region of the global optimum followed by simplex for "fine-tuning" is often effective [18].

Q3: When optimizing mobile phase composition, how do I choose between acetonitrile and methanol?

Acetonitrile is generally preferred for high-throughput systems due to its lower viscosity and lower backpressure, while methanol is more cost-effective for routine analyses [29]. Methanol has a higher UV cutoff than acetonitrile, which may affect baseline noise in UV detection [28]. The choice should be based on the specific separation requirements, detector compatibility, and cost considerations.

Q4: How can I tell if peak tailing is caused by secondary interactions with the stationary phase?

Secondary interactions with residual silanol groups are a common cause of tailing, particularly for basic compounds containing amines or other basic functional groups at pH >3, where both the basic functional groups and silanol groups may be ionized [28]. This can be confirmed by switching to a highly end-capped column or using mobile phase additives like triethylamine that mask silanol groups [28]. Working at low pH (<3, if the column allows) can also minimize this effect by protonating silanol groups [28].

Q5: What is the recommended approach when retention times are consistently decreasing over days or weeks?

Gradual retention time decrease over an extended period may indicate loss of stationary phase due to hydrolysis of siloxane bonds under acidic conditions (pH <2) [27]. To address this, adjust mobile phase conditions to a less acidic pH, use a different, more chemically stable stationary phase, or both [27]. Using a guard column can also help protect the analytical column from harsh mobile phase conditions.

Mobile Phase Optimization: Practical Methodology

Systematic Optimization Approach

Key Optimization Parameters

Solvent Selection Strategy:

- Begin with a water-acetonitrile or water-methanol system for reversed-phase chromatography [29]

- For hydrophilic analytes, use more polar solvents; for hydrophobic compounds, use less polar options [29]

- Consider viscosity effects on backpressure - acetonitrile/water mixtures typically generate lower backpressure than methanol/water [29]

pH Optimization Guidelines:

- Adjust pH to within ±1 unit of the analyte's pKa for ionizable compounds [29]

- Use appropriate buffer systems with capacity near their pKa values [29]

- Stay within the column's recommended pH range (typically 2-8 for silica-based columns) to prevent stationary phase degradation [29]

Temperature Considerations:

- Higher temperatures generally reduce viscosity and backpressure [29]

- Temperature affects retention and selectivity, particularly for ionizable compounds

- Maintain consistent temperature using a column oven for reproducible results [26]

FAQs on Sequential Simplex Optimization

Q1: What is sequential simplex optimization, and why is it useful for screening reaction conditions?

Sequential simplex optimization is an evolutionary operation (EVOP) technique used to optimize a system response, such as chemical yield or purity, as a function of several experimental factors. It is a highly efficient experimental design strategy that can optimize a relatively large number of factors in a small number of experiments. Unlike classical approaches that first screen for important factors and then model the system, the simplex method first seeks the optimum combination of factor levels, providing improved response after only a few experiments without the need for detailed mathematical or statistical analysis [31] [18].

Q2: What are the common challenges when using the simplex method for simultaneous yield and purity optimization?

A primary challenge is handling systems with multiple local optima. The simplex method operates efficiently in the region of a local optimum but may not find the global optimum on its own. For complex reactions with significant by-product formation, this is a key consideration [18]. Furthermore, defining a single chromatographic response function (CRF) or objective function that adequately balances the often-competing goals of high yield and high purity can be difficult. The algorithm's performance is directly tied to how well this function represents the overall process goals [32].

Q3: Our simplex optimization seems to have stalled. What could be the cause, and how can we proceed?

Stalling, where moves become very small with no significant improvement in response, typically indicates the algorithm has found an optimum (which may be local). To proceed:

- Verify the optimum: Perform a small confirmatory experiment to check the response.

- Check for a local optimum: If the performance is unsatisfactory, you may be in a local optimum. Restart the simplex from a different initial set of factor levels to explore other regions of the factor space [18].

- Refine your objective function: Ensure your response function (e.g., combining yield and purity metrics) correctly reflects your process goals [33].

Q4: How can we make the optimization process more efficient and robust?

Implementing an efficient stop criterion is crucial to prevent unnecessary experiments. One advanced method involves the continuous comparison of the actual chromatographic response function with the predicted value [32]. Furthermore, for complex reactions, using inline analytics (like FT-IR) and online analytics (like mass spectrometry) as feedback for the algorithm allows for real-time, model-free autonomous optimization, dramatically speeding up process development [33].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: The algorithm oscillates or performs poorly after a good start.

- Potential Cause: The simplex may be traversing a steep ridge on the response surface.

- Solution: Apply a modified simplex algorithm that includes rules for contraction and expansion. This allows the simplex to change shape and adapt to the response surface topography more effectively, leading to more stable convergence [33].

Problem: The optimization results are inconsistent or difficult to reproduce.

- Potential Cause 1: Poor experimental control or analytical measurement error.

- Solution: Review your experimental setup for consistency in factors like temperature control and reactant mixing. Ensure your analytical methods (e.g., HPLC, FT-IR) are calibrated and provide reproducible data [33].

- Potential Cause 2: The chosen factors have complex interactions that the simplex is struggling to resolve.

- Solution: Once in the general region of the optimum, use a classical experimental design (like a central composite design) to model the system in that local region. This can provide a deeper understanding of factor interactions and verify the optimum found by the simplex [18].

Problem: Optimization fails to achieve the desired purity threshold even when yield is high.