Simplex Optimization in Liquid Chromatography: A Modern Guide for Method Development in Pharmaceutical Analysis

This article provides a comprehensive examination of the Simplex optimization method for developing and refining Liquid Chromatography (LC) methods, a critical process in pharmaceutical and biomedical research.

Simplex Optimization in Liquid Chromatography: A Modern Guide for Method Development in Pharmaceutical Analysis

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive examination of the Simplex optimization method for developing and refining Liquid Chromatography (LC) methods, a critical process in pharmaceutical and biomedical research. It covers foundational principles, including how the sequential Simplex algorithm efficiently navigates the multi-parameter space of LC conditions. The guide details practical implementation strategies for separating complex mixtures, from natural products to pharmaceuticals, and addresses common troubleshooting scenarios. Furthermore, it positions Simplex within the modern analytical landscape by comparing its performance against advanced alternatives like Bayesian Optimization and Reinforcement Learning. Designed for researchers and lab professionals, this resource offers actionable insights to accelerate method development while ensuring robust, high-quality separations.

Simplex Optimization Fundamentals: Mastering Core Principles for Efficient LC Method Scouting

Historical Context and Fundamental Principles

The sequential simplex procedure emerged as a efficient optimization method for liquid chromatography (LC) parameters, providing a systematic approach to method development that significantly reduced the time and resources required to achieve optimal separations. The foundational work on simplex optimization was established by Spendley, Hext, and Himsworth in 1962 [1], creating a mathematical framework for experimental optimization that would later be adapted for chromatographic applications. This method represents a cornerstone in the broader thesis research on liquid chromatography parameter optimization, demonstrating how algorithmic approaches can enhance analytical precision and efficiency.

Chromatography itself operates on the principle of separating mixture components based on their differential interactions with two phases: a stationary phase (fixed material) and a mobile phase (moving fluid) [2]. As the mobile phase carries the sample through the stationary phase, each component moves at distinct speeds determined by properties like molecular size, charge, or affinity, ultimately resulting in separation [2]. The sequential simplex method brought mathematical rigor to optimizing the numerous variables governing these interactions.

The fundamental principle of sequential simplex optimization involves navigating the experimental parameter space through a geometric construct called a "simplex" – a multidimensional shape with n+1 vertices in an n-dimensional factor space. The procedure follows a logical sequence of experiments where the worst-performing vertex is successively replaced by its reflection through the centroid of the remaining vertices, steadily moving the simplex toward optimum conditions. This approach proved particularly valuable in chromatography, where multiple interacting parameters such as mobile phase composition, temperature, and flow rate collectively influence separation quality, making one-factor-at-a-time optimization strategies inefficient and potentially misleading.

Application Notes: Implementation in Liquid Chromatography

Key Optimization Parameters in Liquid Chromatography

The sequential simplex method has been successfully applied to optimize numerous critical parameters in high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), which directly impact separation efficiency, resolution, and analysis time. Mobile phase composition stands as the most frequently optimized parameter, particularly in reversed-phase HPLC, where the proportions of organic modifiers (e.g., methanol, acetonitrile, 2-propanol) in aqueous buffers profoundly affect analyte retention and selectivity [3] [4]. Even early applications demonstrated that simplex optimization could efficiently identify optimal ternary or quaternary mobile phase mixtures that would be impractical to locate through exhaustive trial-and-error experimentation [1] [3].

Flow rate and column temperature represent additional critical parameters amenable to simplex optimization. Several studies have systematically optimized these factors to achieve balances between analysis time, resolution, and back-pressure constraints [5] [6]. In preparative liquid chromatography, where production rate and yield become paramount, simplex optimization has identified conditions that dramatically enhance throughput while maintaining acceptable separation quality [5]. The method has proven particularly valuable when multiple parameters require simultaneous optimization, as the simplex algorithm efficiently navigates the complex response surfaces generated by interacting factors.

Table 1: HPLC Parameters Optimized via Sequential Simplex Procedure

| Parameter Category | Specific Parameters | Chromatographic Impact | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mobile Phase | Organic modifier percentage, pH, buffer concentration | Retention factor (k), selectivity (α), resolution (Rs) | Separation of benzodiazepines [7] |

| Flow Dynamics | Flow rate, gradient profile, gradient time | Analysis time, back pressure, peak capacity | Biogenic amines in fish [4] |

| Column Conditions | Column temperature | Retention, efficiency (N), selectivity | Capsaicinoid compounds [6] |

| Performance Metrics | Production rate, yield, purity | Throughput, cost-effectiveness | Preparative LC [5] |

Chromatographic Response Functions

A critical component of successful simplex optimization in chromatography is the definition of an appropriate chromatographic response function (CRF) that mathematically quantifies separation quality. The CRF serves as the objective function that the simplex algorithm seeks to maximize or minimize, numerically representing the "goodness" of a chromatographic separation. Research has demonstrated that effective CRFs typically incorporate multiple separation characteristics, including resolution between critical peak pairs, total analysis time, peak symmetry, and sensitivity [1] [4].

Early implementations used relatively simple CRFs that weighted resolution between adjacent peaks, while later developments incorporated more sophisticated functions that balanced separation quality with analysis time [1] [3]. For example, some applications employed an overall desirability function that combined multiple response metrics into a single value, enabling the simultaneous optimization of seemingly competing objectives such as maximum resolution and minimum analysis time [3]. The development of effective CRFs represented a significant advancement in chromatographic optimization, as it enabled the automation of method development through computer-controlled HPLC systems that could conduct experiments without operator intervention [8].

Experimental Protocols

Sequential Simplex Optimization Protocol for HPLC Method Development

Purpose: To systematically optimize multiple HPLC parameters using the modified sequential simplex algorithm for the separation of complex mixtures.

Materials and Equipment:

- HPLC system with programmable pumps, column thermostat, and detector

- Chromatography data system software

- Analytical column appropriate for the application

- HPLC-grade solvents and reagents

- Standard mixture of analytes of interest

Procedure:

Factor Selection and Boundary Definition:

- Select 2-4 critical parameters to optimize (e.g., %organic solvent, flow rate, temperature, gradient time)

- Define practical boundaries for each parameter based on column specifications, instrument capabilities, and chemical constraints

Initial Simplex Construction:

- Establish an initial simplex with n+1 vertices (where n = number of factors)

- For two factors, this creates a triangle; for three factors, a tetrahedron

- Calculate factor levels for each vertex using standard simplex initialization algorithms

Chromatographic Response Function Definition:

- Develop a CRF that quantitatively measures chromatographic performance

- Example CRF:

CRF = ΣRs + k'min - (tmax - tmin) - wmaxwhere:- ΣRs = sum of resolutions between adjacent peaks

- k'min = minimum acceptable retention factor

- tmax, tmin = maximum and minimum retention times

- wmax = maximum peak width

Sequential Experimentation:

- Run experiments at each vertex of the initial simplex

- Calculate CRF value for each chromatogram

- Identify vertex with worst CRF value

- Reflect worst vertex through centroid of remaining vertices to generate new vertex

- Run experiment at new vertex conditions

- Continue process according to simplex rules (reflection, expansion, contraction)

Termination:

- Continue iterations until simplex converges on optimum

- Apply stop criterion based on continuous comparison of attained CRF with predicted optimum or when further improvements become negligible [1]

- Verify optimal conditions with replicate injections

Troubleshooting Notes:

- If simplex cycles without convergence, consider redefining factor boundaries or CRF

- If unexpected chromatographic behavior occurs, check for parameter interactions not captured in CRF

- For complex mixtures, incorporate peak tracking algorithms based on spectral characteristics [1]

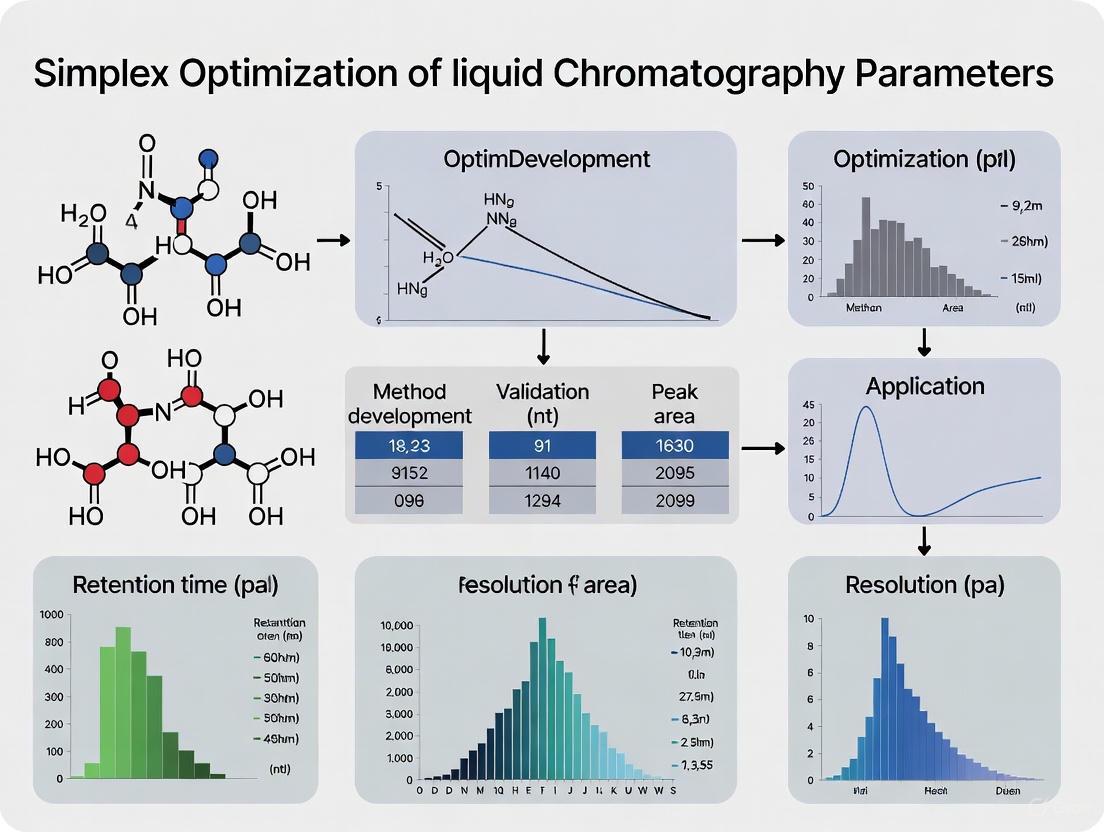

Diagram 1: Sequential Simplex Optimization Workflow for HPLC Method Development

Protocol for Biogenic Amine Separation Using Simplex-Optimized Conditions

Purpose: To separate and quantify biogenic amines in fish samples using ion-exchange HPLC with conditions optimized via the simplex procedure [4].

Optimized Materials:

- Ion-exchange column (e.g., cation-exchange)

- Mobile phase A: Aqueous buffer

- Mobile phase B: 2-propanol with buffer

- Fluorescence or UV detection

- Standard solutions of biogenic amines

Simplex-Optimized Conditions [4]:

- Organic Modifier: 12.7% 2-propanol in mobile phase

- Gradient Program: Specific curve optimized via simplex

- Flow Rate: 1.0 mL/min (constant)

- Column Temperature: 35°C

- Detection: Fluorescence with appropriate excitation/emission wavelengths

Chromatographic Procedure:

- Prepare mobile phases according to optimized proportions

- Equilibrate column with starting mobile phase composition for ≥30 minutes

- Set gradient program to simplex-optimized profile

- Inject 20 μL of extracted fish sample or standard

- Monitor separation over 16-minute runtime

- Quantify amines based on peak areas relative to standards

Validation Parameters:

- Linear range: 0.5-50 mg/L for most amines

- Detection limits: 0.06 mg/L for histamine to 0.22 mg/L for tryptamine

- Retention time RSD: <12% for all amines

Advanced Applications and Case Studies

Representative Case Studies in Pharmaceutical and Food Analysis

The sequential simplex method has demonstrated particular utility in pharmaceutical analysis, where complex mixtures of structurally similar compounds present significant separation challenges. In one notable application, researchers developed an HPLC method for benzodiazepines using the modified simplex procedure to optimize the separation of multiple psychotherapeutic compounds [7]. The optimization focused on mobile phase composition and gradient profile, ultimately achieving baseline separation of these structurally similar molecules with significantly improved resolution compared to initial conditions. This application highlighted the method's ability to navigate complex factor spaces where traditional one-variable-at-a-time optimization would likely miss the global optimum.

In food science, the simplex procedure enabled the development of a rapid method for biogenic amine analysis in fish samples [4]. By optimizing the proportion of 2-propanol in the mobile phase and specific gradient profile steps, researchers reduced analysis time from 25 to 16 minutes while maintaining resolution for nine biogenic amines. This acceleration in analysis time significantly enhanced laboratory throughput while providing the necessary separation power for accurate quantification of food spoilage markers. The method demonstrated excellent linearity (R² > 0.99 for most amines) and detection limits suitable for monitoring regulatory compliance [4].

Table 2: Historical Applications of Sequential Simplex in Chromatography

| Application Domain | Analytes | Optimized Parameters | Key Outcomes | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pharmaceutical Analysis | Benzodiazepines | Mobile phase composition, gradient profile | Baseline separation of structurally similar compounds | [7] |

| Food Safety | Biogenic amines in fish | 2-propanol percentage, gradient curve | 9-minute reduction in analysis time (25 to 16 min) | [4] |

| Natural Products | Capsaicinoids in chili | Solvent composition, flow rate, temperature | Enhanced resolution and reliability for quality control | [6] |

| Preparative LC | Binary mixtures | Flow velocity, sample size, column length | Maximized production rate and yield | [5] |

Integration with Advanced Detection and Peak Tracking Technologies

A significant advancement in sequential simplex applications came with its integration to multichannel detection systems, which addressed the critical challenge of peak tracking during method optimization [1]. As chromatographic conditions change throughout the simplex procedure, retention times shift, making it difficult to consistently identify the same analyte across different experiments. Researchers developed innovative solutions to this problem by leveraging spectral data from diode array detectors to create peak homogeneity tests and algorithms for assigning peak elution order based on area ratios at multiple wavelengths [1].

This integration represented a substantial step forward in automation capability, as it enabled unattended optimization of complex separations without requiring manual peak identification at each vertex. The approach utilized the wavelength sensitivity of chromatographic peak maxima to verify peak purity and identity, essentially creating a fingerprint for each analyte that remained consistent even as retention times shifted with changing mobile phase composition [1]. This technological synergy between simplex optimization algorithms and advanced detection capabilities significantly expanded the method's applicability to complex real-world samples where peak tracking presents a major challenge.

Research Reagent Solutions

The implementation of sequential simplex optimization in chromatography requires specific materials and reagents that enable precise parameter control and sensitive detection. The following table details essential research reagents and their functions in simplex-optimized chromatographic methods.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Simplex-Optimized Chromatography

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| C18 Stationary Phases | Reverse-phase separation medium | Most common; particle size (1.7-5μm) affects efficiency and pressure [2] |

| Protein A Affinity Resins | Capture antibodies in MCC | Critical for MAb capture; resin utilization improved by 80% with MCC [9] |

| Acetonitrile & Methanol | Organic mobile phase modifiers | Different selectivity; acetonitrile offers lower viscosity [3] |

| Ion-Pairing Reagents | Modify retention of ionic analytes | e.g., TFA for proteins; alkyl sulfonates for bases [4] |

| Buffers (phosphate, acetate) | Control mobile phase pH | Critical for ionizable compounds; typically 10-100 mM [4] |

| Multi-Column Systems (BioSMB) | Continuous chromatography | Enables sequential loading; increases resin utilization [9] |

Contemporary Relevance and Technological Evolution

While the fundamental sequential simplex algorithm remains largely unchanged since its early applications in chromatography, its implementation has evolved significantly through integration with modern instrumentation and data systems. Contemporary chromatography data systems often include built-in optimization modules that incorporate simplex algorithms alongside other optimization strategies, making the method more accessible to practicing chromatographers [2]. These systems frequently include automated peak tracking capabilities that address one of the most challenging aspects of chromatographic optimization – maintaining consistent peak identity as conditions change.

The sequential simplex method continues to provide value in specific application niches, particularly when dealing with a limited number of critical parameters that require optimization. Its historical success has paved the way for more sophisticated optimization approaches, including overlapping resolution mapping (ORM) and computer-aided method development systems that leverage extensive databases of chromatographic parameters [3]. Furthermore, the emergence of multi-column chromatography (MCC) systems represents a different manifestation of the "simplex" concept, where multiple columns are operated in sequence or parallel to enhance throughput and resin utilization in preparative applications [9]. These modern systems can achieve up to 80% reduction in resin volumes and costs while maintaining separation efficiency, demonstrating how the fundamental principles of systematic optimization continue to influence chromatographic practice.

Liquid Chromatography (LC) method development requires the simultaneous optimization of multiple, often interacting, parameters to achieve robust and high-performance separations. Key parameters such as the gradient profile, column temperature, and mobile phase flow rate form a complex optimization landscape where a change in one variable can significantly impact the effects of others. Traditional univariate optimization methods, which vary one parameter at a time, are not only time-consuming but also risk missing the true optimum due to these parameter interactions [10]. Simplex optimization is a powerful multivariate strategy designed to efficiently navigate this complexity. It is an iterative algorithm that systematically adjusts all parameters at once to find the optimal conditions, making it particularly valuable for researchers and drug development professionals aiming to maximize critical outcomes such as resolution, peak capacity, and analysis speed [11] [12].

The fundamental principle of simplex optimization is based on a geometric concept. For an optimization problem with n variables, the simplex is a geometric figure defined by n+1 points in the n-dimensional parameter space [12]. In a typical LC application involving gradient, temperature, and flow rate (n=3), the simplex would be a tetrahedron. The algorithm proceeds by running experiments at the conditions defined by each vertex, evaluating the response (e.g., a resolution function), and then intelligently moving the vertex with the worst performance through the opposite face of the simplex to a new point. This process of reflection, expansion, and contraction is repeated, causing the simplex to "walk" across the response surface towards the optimum conditions [11]. Unlike methods that require calculating derivatives, the simplex method is a direct search algorithm, making it robust and applicable to a wide range of experimental challenges without needing a precise mathematical model of the system [10].

Key Parameters and Their Interactions

The separation quality in Liquid Chromatography is governed by the interplay of several critical operational parameters. Understanding these parameters and their interactions is the first step in defining the optimization problem.

- Gradient Profile: In reversed-phase LC, this typically refers to the time-dependent program for increasing the percentage of the organic modifier (e.g., acetonitrile or methanol) in the mobile phase. The gradient slope (the rate of change), initial and final compositions directly control retention and is a primary driver of peak capacity and resolution [13]. The linear solvent strength (LSS) theory provides a model for understanding and predicting retention times as a function of gradient conditions [13].

- Column Temperature: This parameter affects the viscosity of the mobile phase and the thermodynamics of analyte partitioning between the mobile and stationary phases. Increasing temperature typically reduces retention and can improve efficiency by enhancing analyte diffusion coefficients. Its interaction with the gradient profile is significant, as temperature can modulate the effective solvent strength experienced by the analytes.

- Flow Rate: This determines the linear velocity of the mobile phase through the column. According to van Deemter theory, flow rate has a direct and non-linear impact on chromatographic efficiency (plate height). It also affects the backpressure of the system and the total runtime of the analysis.

The following table summarizes these key parameters, their typical effects, and their primary interactions.

Table 1: Key LC Parameters for Simplex Optimization and Their Interactions

| Parameter | Typical Effect on Separation | Interaction with Other Parameters |

|---|---|---|

| Gradient Profile | Primarily controls retention and peak capacity. A steeper gradient reduces runtime but may compromise resolution [13]. | Interacts with temperature; a higher temperature can mimic the effect of a stronger eluent. Interacts with flow rate to determine the effective gradient volume delivered to the column. |

| Column Temperature | Impacts efficiency and retention. Higher temperatures often sharpen peaks and shorten analysis time. | Interacts with the gradient profile; the optimal temperature program is dependent on the chosen gradient conditions and vice-versa. |

| Flow Rate | Affects efficiency (plate height) and system backpressure. Higher flow rates reduce runtime but can lower efficiency. | Interacts with the gradient profile; the product of flow rate and gradient time determines the total volume of mobile phase used, influencing the effective gradient steepness. |

Experimental Protocols for Simplex Optimization

Defining the Optimization Problem and Pre-experimental Setup

Objective: To develop an optimized LC method for the separation of a complex mixture of psychotherapeutic benzodiazepines by simultaneously adjusting gradient time, column temperature, and flow rate to maximize the calculated resolution factor (Rs) [7].

Materials and Equipment:

- HPLC System: A binary or quaternary pump system capable of delivering precise gradients, a thermostatted column compartment, and a UV-Vis or DAD detector.

- Chromatography Column: A suitable reversed-phase C18 column (e.g., 150 mm x 4.6 mm, 5 µm).

- Chemicals and Reagents: HPLC-grade water, acetonitrile (or methanol), and analytical standards of the target benzodiazepines.

- Software: Instrument control and data acquisition software. A platform capable of running an automated sequence or custom script to facilitate the simplex algorithm (e.g., via Python or a dedicated instrument control library) is ideal.

Pre-optimization Steps:

- Scouting Runs: Perform initial isocratic and gradient runs to determine the approximate elution window of the sample mixture. This helps in defining a reasonable starting point and range for the gradient.

- Define the Response Function (RF): The success of each experiment must be quantified by a single numerical value. A common response function for chromatographic optimization is a resolution factor that penalizes peak overlap. An example function is:

( RF = \sum \ln(Rsi) )

where ( Rsi ) is the resolution between adjacent peak pairs

i. This function aims to maximize the overall resolution, with a minimum acceptable value (e.g., Rs > 1.5) for all critical peak pairs. - Set Variable Boundaries: Establish safe operating limits for each parameter to prevent column or instrument damage.

- Gradient Time (tG): 5 to 60 minutes

- Column Temperature (T): 25 to 60 °C

- Flow Rate (F): 0.8 to 1.5 mL/min

Implementing the Modified Simplex Workflow

The following protocol outlines the steps for a modified simplex procedure, which incorporates expansion and contraction operations for faster and more robust convergence compared to the basic simplex method [11] [12].

Table 2: Simplex Operations and Their Conditions

| Operation | Mathematical Expression | When to Apply |

|---|---|---|

| Reflection | ( xr = \bar{x} + \alpha(\bar{x} - xw) ) | Standard step after initial evaluation. |

| Expansion | ( xe = \bar{x} + \gamma(xr - \bar{x}) ) | If ( RF(x_r) ) is the best response so far. |

| Contraction | ( xc = \bar{x} + \beta(xw - \bar{x}) ) | If ( RF(xr) ) is worse than ( RF(xs) ) (the second-worst response). |

| Total Contraction | Shrink all vertices towards the best vertex ( x_b ). | If ( RF(xr) ) is worse than ( RF(xw) ). |

Legend: ( \bar{x} ): Centroid of all vertices except the worst (x_w). Typical coefficients: ( \alpha = 1.0, \gamma = 2.0, \beta = 0.5 ).

The logical workflow for implementing this protocol is visualized in the following diagram.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Initialization: Generate the initial simplex. For three parameters (n=3), four (n+1) initial experimental conditions (vertices) are required. A common approach is to choose one vertex as the best-known conditions from pre-scouting and generate the others by small perturbations of each parameter from this base point [12].

- Evaluation and Ranking: Run the chromatographic experiments at the conditions specified by each vertex of the simplex. Calculate the Response Function (RF) for each chromatogram. Rank the vertices from best (highest RF) to worst (lowest RF).

- Simplex Transformation:

a. Calculate Centroid: Compute the centroid

x̄of all vertices excluding the worst vertexx_w. b. Reflection: Generate a new vertexx_rby reflectingx_wthrough the centroid. Run the experiment and calculateRF(x_r). c. Decision Logic: * IfRF(x_r)is better thanRF(x_b), an expansion is triggered. Calculate and test an expanded vertexx_e. Ifx_eis better thanx_r, replacex_wwithx_e; otherwise, replacex_wwithx_r. * IfRF(x_r)is worse thanx_bbut better thanx_s, it is an improvement. Replacex_wwithx_r. * IfRF(x_r)is worse thanx_s, a contraction is performed. Calculate and testx_c. Ifx_cis better thanx_w, replacex_wwithx_c. * If the contracted pointx_cis not an improvement, a total contraction is performed, where the entire simplex is shrunk towards the best vertexx_b. - Convergence Check: After each iteration, check if the algorithm has converged. A common criterion is that the standard deviation of the response function values across the simplex vertices falls below a pre-defined threshold (e.g., 2-5% of the mean response), indicating that no further significant improvement is likely [12].

- Termination: The process terminates when the convergence criterion is met. The vertex with the best response function is reported as the optimal set of conditions.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details the essential materials and solutions required to execute the simplex optimization protocol described above.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions and Materials for LC Simplex Optimization

| Item | Function / Role in Optimization |

|---|---|

| HPLC-grade Water | The aqueous component of the mobile phase; serves as the weak solvent in reversed-phase chromatography. Must be high purity to minimize baseline noise and ghost peaks. |

| HPLC-grade Acetonitrile/Methanol | The organic modifier component of the mobile phase; serves as the strong solvent. Its composition is varied during the gradient to elute analytes from the stationary phase. |

| Analytical Reference Standards | Pure samples of the target analytes (e.g., specific benzodiazepines). Essential for identifying peaks in the chromatogram and accurately calculating the resolution response function [7]. |

| Phosphate or Formate Buffers | Used to control the pH of the aqueous mobile phase, which can critically impact the ionization state and retention of ionizable analytes, thereby affecting selectivity. |

| C18 Reversed-Phase Column | The stationary phase where chromatographic separation occurs. The choice of column dimensions (length, internal diameter, particle size) and ligand chemistry is fundamental to the separation mechanism. |

In the field of liquid chromatography (LC) method development, researchers and pharmaceutical scientists continually face the challenge of optimizing multiple interdependent parameters to achieve optimal separations. The sequential simplex method represents a powerful multivariable optimization strategy that enables systematic navigation of complex parameter spaces to identify conditions that maximize chromatographic performance. Unlike one-variable-at-a-time approaches, which risk missing optimal conditions due to parameter interactions, simplex optimization simultaneously adjusts all variables according to a defined set of movement rules. This approach has demonstrated significant utility across various chromatographic applications, including the analysis of capsaicinoid compounds in Thai capsicum fruits, the separation of heavy metal complexes, and the purification of biopharmaceuticals [6] [14] [15].

The fundamental principle of simplex optimization relies on a geometric construct known as a simplex—a polytope of (n + 1) vertices in (n)-dimensional space, where each vertex represents a unique combination of experimental parameters [12]. Through iterative application of movement rules, the simplex progressively navigates the parameter space, discarding unfavorable conditions and moving toward regions that improve the chromatographic response. This article provides a comprehensive examination of the movement mechanics—reflection, expansion, and contraction—that govern this sophisticated optimization technique, with specific application to LC parameter optimization for drug development professionals.

Fundamental Movement Rules of the Simplex Algorithm

Mathematical Foundation and Core Principles

The simplex algorithm operates on the principle of iterative improvement, where a simplex—comprising (n+1) experimental points in (n)-dimensional parameter space—evolves toward an optimum through defined geometric transformations [12]. Each vertex of the simplex represents a unique combination of chromatographic parameters, such as mobile phase composition, flow rate, column temperature, or gradient conditions, with the associated chromatographic response quantified by a Chromatographic Response Function (CRF). This CRF typically incorporates critical separation metrics including the number of peaks, resolution between adjacent peaks, total analysis time, and retention factors relative to a minimum threshold [14] [1] [16].

The algorithm begins by evaluating the CRF at each vertex of the initial simplex, identifying the worst-performing vertex ((X_w)) which yields the least favorable chromatographic response. This vertex is subsequently discarded and replaced through a series of geometric operations, each governed by specific coefficients that determine the size and direction of movement within the parameter space. The primary movement rules—reflection, expansion, and contraction—are mathematically defined as follows [12]:

- Reflection: (Xr = Xc + \alpha(Xc - Xw)), where (\alpha > 0) is the reflection coefficient

- Expansion: (Xe = Xc + \gamma(Xr - Xc)), where (\gamma > 1) is the expansion coefficient

- Contraction: (Xt = Xc + \beta(Xw - Xc)), where (0 < \beta < 1) is the contraction coefficient

In these equations, (Xc) represents the centroid of the remaining vertices after excluding (Xw), calculated as the average coordinates of all vertices except (X_w). The standard Nelder-Mead simplex algorithm typically employs coefficient values of (\alpha = 1), (\gamma = 2), and (\beta = 0.5) [12].

Decision Logic for Movement Operations

The simplex algorithm follows a precise decision pathway when navigating the parameter space. After calculating the reflected point ((X_r)), the algorithm evaluates the chromatographic response at this new position and compares it against responses at other simplex vertices to determine the appropriate subsequent operation. The standard decision logic for these movement operations follows a well-defined pathway, illustrated in Figure 1 and detailed below:

Reflection Operation: The algorithm first computes the reflection vertex ((Xr)) and its corresponding response ((Rr)). If (Rr) is superior to the second-worst response ((Rs)) but inferior to the best response ((Rb)), the reflection is accepted, and (Xw) is replaced with (X_r) to form a new simplex for the next iteration [12].

Expansion Operation: If the reflection produces a response ((Rr)) superior to the current best response ((Rb)), the algorithm performs an expansion to (Xe) and evaluates the response ((Re)). If (Re > Rr), the expansion is accepted, replacing (Xw) with (Xe); otherwise, (X_r) is accepted. This operation allows for accelerated progress toward promising regions of the parameter space [12].

Contraction Operations: When reflection yields a response ((Rr)) worse than (Rs), contraction is initiated. The algorithm distinguishes between two scenarios: if (Rr) is better than (Rw) but worse than (Rs), "outside contraction" is performed toward (Xr); if (Rr) is worse than or equal to (Rw), "inside contraction" is performed away from (Xw). If the contracted point ((Xt)) yields an improved response over (X_w), the contraction is accepted; otherwise, a reduction operation is performed [12].

The algorithm terminates when the responses at all vertices fall below a predefined convergence threshold or when a maximum number of iterations is reached. For chromatographic applications, an efficient stopping criterion often involves continuous comparison between attained and predicted CRF values [1].

Experimental Protocols for Simplex Optimization in Liquid Chromatography

Protocol 1: Implementing Simplex Optimization for Isocratic HPLC Separation

This protocol outlines the systematic optimization of an isocratic high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) method using the sequential simplex algorithm, suitable for pharmaceutical analysis where resolution of multiple components must be balanced with analysis time.

Required Materials and Reagents:

- HPLC System: Binary or quaternary pump with auto-sampler and tunable UV/Vis or DAD detector

- Chromatographic Column: Appropriate stationary phase (e.g., C18, C8, phenyl)

- Mobile Phase Components: HPLC-grade solvents (acetonitrile, methanol), water, and buffer salts

- Standard Solutions: Target analytes dissolved in suitable solvent

- Software: Chromato-graphic data system capable of calculating resolution, peak asymmetry, and retention times

Table 1: Research Reagent Solutions for Simplex Optimization in HPLC

| Reagent/Material | Function in Optimization | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Acetonitrile (HPLC-grade) | Organic modifier in mobile phase to adjust retention | 28.6% in mobile phase for heavy metal PAR chelates [14] |

| Tetrabutylammonium bromide (TBABr) | Ion-pairing reagent to modify selectivity | 5.2 mmol/L for metal chelate separation [14] |

| Acetate buffer | pH control for retention and selectivity optimization | 3.0 mmol/L at pH 6.0 [14] |

| C18 chromatographic column | Stationary phase for reverse-phase separation | Standard column for capsaicinoid analysis [6] |

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Define Optimization Parameters and Ranges: Select critical chromatographic variables to optimize based on preliminary experiments. Typical parameters include:

- Organic modifier concentration (% acetonitrile or methanol): ±10-20% range

- Buffer concentration: ±2-5 mM range

- Buffer pH: ±0.5-1.0 unit range

- Flow rate: ±0.1-0.5 mL/min range

- Column temperature: ±5-10°C range

Establish Chromatographic Response Function (CRF): Define a CRF that incorporates key separation metrics. A typical function may include [14] [16]:

- Number of detected peaks

- Resolution between critical peak pairs

- Total analysis time

- Retention factors of first and last peaks

Example CRF: ( CRF = \sum Rs + (N{peaks} \times weighting) - (t{last} - t{first}) )

Initialize Simplex: For (n) parameters, create an initial simplex of (n+1) experiments. The first vertex represents baseline conditions, with subsequent vertices generated by varying one parameter at a time by a predetermined step size.

Execute Sequential Optimization:

- Run experiments for each vertex of the current simplex

- Calculate CRF values for each vertex

- Identify worst vertex ((Xw)) and compute centroid ((Xc)) of remaining vertices

- Apply reflection, expansion, or contraction based on decision rules

- Replace (X_w) with new vertex to form new simplex

Monitor Convergence: Continue iterations until the difference in CRF values between the best and worst vertices falls below a predetermined threshold (e.g., <5% variation) or until no further improvement is observed after multiple iterations.

Validate Optimum: Confirm the predicted optimum conditions with replicate injections to verify method robustness and reproducibility.

Protocol 2: Simplex Optimization of Gradient Elution Parameters

This protocol specifically addresses the optimization of gradient elution parameters, particularly valuable for complex samples where isocratic conditions fail to provide adequate resolution within a reasonable analysis time.

Required Materials and Reagents:

- HPLC System with gradient capability and precise mixing

- Columns and Mobile Phases as in Protocol 1

- Standard Mixture representing sample complexity

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Define Gradient Parameters: Select gradient-related variables for optimization:

- Initial organic solvent concentration (%B)

- Final organic solvent concentration (%B)

- Gradient time ((t_G))

- Gradient shape (linear, curved)

- Equilibration time

Establish Time-Weighted CRF: Create a response function that balances resolution requirements with analysis time constraints, incorporating both resolution factors and a maximum acceptable analysis time [16].

Implement Simplex Operations: Follow the same iterative process as Protocol 1, applying reflection, expansion, and contraction rules to navigate the gradient parameter space.

Address Mobile Phase Compatibility: Ensure that the optimized gradient conditions maintain compatibility with detection systems, particularly when using mass spectrometry.

Verify Method Transferability: Assess the robustness of optimized gradient conditions across different instruments and columns to ensure practical utility.

Application Case Studies in Pharmaceutical Analysis

Case Study 1: Optimization of Capsaicinoid Compound Separation

Research on the determination of capsaicinoid compounds in Thai capsicum fruits demonstrates the practical application of sequential simplex optimization in food and pharmaceutical analysis. The study focused on optimizing HPLC parameters including solvent composition, flow rate, and column temperature to achieve rapid analysis with optimal separation. Using the simplex method, researchers systematically navigated this three-dimensional parameter space, significantly enhancing the reliability of analytical techniques for pharmaceutical applications [6].

The optimization process resulted in a robust method capable of efficiently separating structurally similar capsaicinoids, which are relevant for both culinary and pharmaceutical applications due to their bioactive properties. This case highlights how simplex optimization can balance multiple competing objectives in chromatographic method development, particularly when analyzing natural product extracts with complex matrices.

Case Study 2: Heavy Metal Analysis via Ion-Pair Reversed-Phase HPLC

A compelling example of simplex optimization in analytical chemistry involves the IP-RPHPLC analysis of Co(II), Ni(II), and Cr(III) as PAR chelates. Researchers employed a sequential simplex algorithm to optimize three experimental parameters: acetonitrile concentration (28.6%), acetate buffer concentration (3.0 mmol/L at pH 6.0), and tetrabutylammonium bromide concentration (5.2 mmol/L) [14].

Table 2: Optimized Conditions for Heavy Metal PAR Chelate Separation

| Parameter | Initial Range | Optimized Value |

|---|---|---|

| Acetonitrile (%) | 20-40% | 28.6% |

| Acetate buffer (mmol/L) | 1-5 mmol/L | 3.0 mmol/L |

| TBABr (mmol/L) | 1-7 mmol/L | 5.2 mmol/L |

| Elution order | N/A | Co(II)PAR, Cr(III)PAR, Ni(II)PAR |

| Analysis time | N/A | 15 minutes |

The optimization process achieved complete resolution of the three metal chelates with an analysis time of 15 minutes, requiring only 19 experiments to reach the optimum conditions. This case study demonstrates the efficiency of the simplex approach in rapidly converging on optimal conditions while managing multiple interacting parameters [14].

Visualization of Simplex Movement Logic

The following diagram illustrates the decision pathway and movement operations of the sequential simplex algorithm in navigating a two-dimensional parameter space, with specific application to chromatographic optimization.

Figure 1: Decision Logic of Sequential Simplex Algorithm

This flowchart illustrates the complete decision pathway for the sequential simplex algorithm, showing how the method evaluates chromatographic responses at each vertex and determines appropriate movement operations to efficiently navigate the parameter space toward optimal separation conditions.

Advanced Considerations for Chromatographic Optimization

Integration with Multichannel Detection

Modern HPLC systems often incorporate multichannel detection, such as diode array detectors (DAD), which provide additional dimensionality to chromatographic data. The integration of simplex optimization with multichannel detection enables more sophisticated assessment of separation quality through peak homogeneity tests and algorithms for assigning peak elution order based on spectral characteristics [1]. This approach is particularly valuable in pharmaceutical analysis where impurity profiling requires both chromatographic resolution and spectral confirmation of peak identity.

The combination of simplex optimization and multichannel detection creates a powerful framework for method development that simultaneously addresses multiple objectives: resolution of critical peak pairs, verification of peak purity, and minimization of analysis time. This integrated approach represents a significant advancement over traditional univariate optimization strategies, particularly for complex samples with co-elution risks or unknown components.

Challenges and Practical Implementation Strategies

While simplex optimization offers significant advantages for chromatographic method development, several practical challenges merit consideration:

Local Optima: The algorithm may converge to local rather than global optima, particularly for complex samples with multimodal response surfaces. Implementation strategies to address this limitation include multi-start approaches with different initial simplex configurations or incorporation of global optimization techniques during initial exploration phases [12].

Experimental Noise: Chromatographic responses inherently contain some degree of variability due to system fluctuations, preparation errors, or detection limitations. Robust implementation requires either replication at critical vertices or application of noise-tolerant simplex variants that incorporate response uncertainty into movement decisions [12].

Constraint Management: Chromatographic parameters often have practical constraints (e.g., pressure limits, solubility boundaries, pH stability ranges). Effective implementation requires incorporating constraint handling mechanisms, such as penalty functions or projection methods, to ensure optimized conditions remain practically feasible [17].

For drug development professionals, the sequential simplex method provides a structured, efficient approach to navigating the complex parameter spaces inherent in liquid chromatography. By understanding and applying the movement mechanics detailed in this article, scientists can develop more robust, efficient analytical methods that accelerate pharmaceutical development while maintaining regulatory compliance.

In the realm of analytical chemistry, particularly in high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), the optimization of separation parameters represents a critical step in method development. Chromatographic Response Functions (CRFs) serve as mathematical criteria that quantitatively assess the quality of a chromatographic separation, transforming complex chromatographic data into a single numerical value that can guide optimization procedures [18] [19]. Within the context of simplex optimization of liquid chromatography parameters, CRFs provide the essential objective function that the algorithm seeks to maximize or minimize, thereby enabling systematic and efficient method development without relying solely on analyst intuition [20] [21].

The development and application of CRFs have evolved significantly to address separation problems of varying complexity, from simple one-dimensional (1D) separations to comprehensive two-dimensional (2D) chromatography [18]. The fundamental challenge in chromatographic optimization lies in the numerous interdependent physical and chemical parameters that affect separation power, including solvent composition, flow rate, column temperature, stationary phase chemistry, and gradient programs [18] [22]. CRFs address this challenge by providing a standardized metric to compare the effectiveness of different chromatographic conditions, balancing critical analytical performance characteristics such as resolution, analysis time, precision, and accuracy [21].

For researchers and drug development professionals, the selection of an appropriate CRF is paramount, as it must align with the specific analytical goals—whether targeted analysis of specific compounds or untargeted characterization of complex mixtures [22]. The integration of CRFs with formal optimization strategies, such as simplex algorithms, represents a powerful synergy that accelerates method development while ensuring robust, transferable methods suitable for regulatory environments [20] [6].

Mathematical Formulations of CRFs

The mathematical foundation of Chromatographic Response Functions varies considerably based on the specific separation objectives and the chromatographic technique employed. Different CRFs emphasize different aspects of separation quality, and understanding their mathematical formulations is essential for selecting the most appropriate function for a given application.

In thin layer chromatography (TLC), CRFs primarily focus on the equal distribution of spots across the separation range. The Multispot Response Function (MRF), developed by De Spiegeleer et al., quantifies how uniformly retention factors (R_F) are distributed between upper (U) and lower (L) limits [19]:

where n is the number of compounds, and RF values are sorted in non-descending order. This function yields values between 0 and 1, with 1 representing ideal equal spacing [19]. Similarly, the Retention Distance (RD) function is sensitive to the minimal distance between spots:

where the product is taken from i=0 to n, with RF0 = 0 and RF(n+1) = 1 [19].

In contrast, high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) typically employs CRFs derived from peak characteristics such as width, retention time, and symmetry [19]. These functions often incorporate the fundamental resolution equation, which expresses separation as the product of three contributions [22]:

where N is the column efficiency (theoretical plate number), α is the selectivity factor, and k is the retention factor. This equation demonstrates that the only means to adjust separation is by modifying parameters affecting efficiency, selectivity, or retention [22].

A comprehensive comparison study of CRFs has revealed that functions which increase monotonically with the number of observed peaks generally perform better in guiding optimization searches, particularly when the number of sample compounds is not known beforehand [23]. Furthermore, CRFs based on the discrimination factor or peak-to-valley ratio can better handle peak asymmetry than those based solely on Snyder resolution (R_s), though this advantage diminishes with increasing noise levels [23].

Table 1: Classification and Characteristics of Common Chromatographic Response Functions

| CRF Type | Mathematical Form | Primary Application | Key Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multispot Response Function (MRF) | MRF = [(U - hRF_n)(hRF_1 - L) Π(hRF_i+1 - hRF_i)] / [((U - L)/(n + 1))^(n+1)] |

TLC | Values between 0-1; ideal for equal-spread assessment | Limited to TLC applications |

| Retention Distance (R_D) | R_D = [(n+1)^(n+1) Π(RF_(i+1) - RF_i)]^(1/n) |

TLC | Sensitive to minimal distance between spots | Requires well-separated spots for accurate assessment |

| Separation Response (D) | D = √[Σ(RF_i - (i-1)/(n-1))] |

TLC | Measures deviation from ideal spot distribution | Less effective when spots are not separated |

| Performance Index (I_p) | I_p = √[Σ(ΔhRF_i - ΔhRF_t)^2 / (n(n+1))] |

TLC/HPLC | Comprehensive performance assessment | Requires predetermined target separation |

| Resolution-Based CRFs | R_s = (√N/4) × (α - 1) × (k/(1 + k)) |

HPLC | Direct relation to fundamental separation parameters | Assumes symmetric peaks; performance decreases with peak asymmetry |

Experimental Protocol: Simplex Optimization of HPLC Parameters for Capsaicinoid Analysis

Background and Objective

This protocol outlines the application of simplex optimization utilizing a chromatographic response function to develop an HPLC method for the determination of capsaicinoid compounds in Capsicum fruits [20] [6]. The sequential simplex method provides a systematic approach for optimizing multiple chromatographic parameters simultaneously to achieve efficient separation within a minimal analysis time [20].

Materials and Equipment

- HPLC System: Liquid chromatograph equipped with UV-Vis detector

- Chromatographic Column: C-8 column (15 cm length × 4.6 mm diameter)

- Chemical Standards: Pure capsaicinoid compounds (e.g., capsaicin, dihydrocapsaicin)

- Mobile Phase: HPLC-grade methanol and water

- Samples: Capsicum fruit extracts

- Data Analysis System: Computer with simplex optimization software

Step-by-Step Procedure

Initial Parameter Selection:

- Begin with literature-based initial conditions for mobile phase composition, flow rate, and column temperature

- Establish a starting simplex with parameter combinations that cover a reasonable experimental domain

CRF Definition and Calculation:

- Define a CRF that incorporates critical separation metrics, typically including resolution between critical pairs, total analysis time, and peak symmetry

- After each chromatographic run, calculate the CRF value to quantitatively assess separation quality

Simplex Optimization Steps:

- Run experiments using the parameter combinations defined by the current simplex vertices

- Calculate CRF values for each vertex and identify the worst-performing combination

- Reflect the worst vertex through the centroid of the remaining vertices to generate a new test point

- Perform a new chromatographic run with the reflected parameters and calculate the new CRF

- Based on the new CRF value, decide whether to accept the new point, expand further, or contract the simplex according to standard simplex rules

- Continue iterations until the CRF reaches a satisfactory value or successive iterations yield no significant improvement (convergence criterion)

Method Validation:

- Once optimal conditions are identified, validate the method for precision, accuracy, linearity, limit of detection (LOD), and limit of quantification (LOQ)

- Apply the optimized method to actual Capsicum samples to confirm performance with real matrices

Expected Outcomes

Using this protocol, researchers can typically achieve complete separation of major capsaicinoid compounds in approximately 11 minutes with optimized parameters including a flow rate of 1.15 mL min⁻¹, column temperature of 43.5°C, and mobile phase composition of 63.7% methanol in water [20]. The simplex-optimized method should demonstrate enhanced resolution, reduced analysis time, and improved reproducibility compared to non-optimized approaches.

Workflow Visualization: Simplex Optimization in Liquid Chromatography

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for implementing simplex optimization of liquid chromatographic parameters using a chromatographic response function as the objective function:

Research Reagent Solutions for Chromatographic Optimization

Successful implementation of chromatographic optimization requires specific reagents and materials that ensure reproducibility, sensitivity, and compatibility with the analytical system. The following table details essential research reagent solutions for method development in pharmaceutical and natural product analysis:

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Chromatographic Method Development and Optimization

| Reagent/Material | Specification | Function in Optimization | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| C-8 Chromatographic Column | 15 cm length × 4.6 mm diameter | Stationary phase providing separation mechanism based on hydrophobic interactions | Capsaicinoid separation [20] [6] |

| Methanol (HPLC Grade) | LC-MS grade, high purity | Organic modifier in reversed-phase mobile phase; affects retention and selectivity | Mobile phase component for capsaicinoid analysis [20] |

| Water (HPLC Grade) | Distilled, LC-MS grade | Aqueous component of mobile phase; dissolution medium for samples | Mobile phase component for capsaicinoid analysis [20] |

| Formic Acid | LC-MS grade, high purity | Mobile phase additive to control pH and improve ionization efficiency in MS detection | Enhancing ionization in LC-MS analysis [24] |

| Ammonium Formate | LC-MS grade, high purity | Buffer salt for maintaining consistent mobile phase pH; affects retention and selectivity | Buffer component in LC-MS methods [24] |

| Reference Standards | Certified purity (>95%) | Quantitative calibration and peak identification | Capsaicin, dihydrocapsaicin for method development [20] |

Advanced Applications and Future Perspectives

The application of CRFs extends beyond conventional one-dimensional liquid chromatography to more advanced separation techniques. In comprehensive two-dimensional liquid chromatography (LC×LC), optimization becomes considerably more complex due to the numerous interdependent parameters affecting both separation dimensions [18] [22]. The optimization strategy for a 2D chromatographic method requires simultaneous consideration of numerous physical and chemical parameters that affect the separation power of the entire methodology [18]. In such cases, CRFs must balance multiple objectives, including peak capacity in both dimensions, analysis time, solvent consumption, and compatibility with detection systems such as mass spectrometry [22].

Emerging trends in the field include the integration of machine learning and chemometric approaches with traditional optimization strategies [22]. These computer-aided workflows can facilitate and/or automate method development by simultaneously optimizing the large number of parameters involved in modern chromatographic systems [22]. For untargeted analyses, where the goal is to characterize the entire sample rather than specific target analytes, CRFs that maximize peak capacity or the number of observed peaks have shown particular utility [22] [23].

The future of chromatographic optimization likely lies in closed-loop automated systems where in-line monitoring coupled with intelligent algorithms continuously adjusts separation parameters to maintain optimal performance despite variations in sample matrices or system conditions [22]. Furthermore, as analytical challenges continue to evolve with increasing sample complexity in pharmaceutical and biological applications, the development of more sophisticated CRFs that incorporate spectral information or predictive models based on molecular structure will enhance our ability to achieve optimal separations with minimal analyst intervention [23].

For researchers engaged in simplex optimization of liquid chromatographic parameters, the strategic selection and application of chromatographic response functions remains fundamental to developing robust, efficient, and transferable analytical methods that meet the rigorous demands of modern drug development and quality control.

In the field of analytical chemistry, particularly in high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) method development, researchers continually seek efficient optimization strategies to achieve robust separation methods. Among various optimization approaches, the simplex method stands out for its distinctive advantages in simplicity, experimental efficiency, and rapid convergence during initial method scouting. This application note details the practical implementation of simplex optimization within liquid chromatography, providing researchers with structured protocols, quantitative performance data, and visual guides to facilitate method development. The content is framed within a broader research thesis on simplex optimization of liquid chromatography parameters, offering both theoretical foundations and practical applications relevant to scientists and drug development professionals engaged in analytical method development.

Key Principles of Simplex Optimization

Simplex optimization represents a class of direct search methods that efficiently navigate the experimental parameter space to locate optimal conditions. Unlike univariate approaches that optimize one factor at a time while holding others constant, simplex methods vary all parameters simultaneously, enabling identification of potential factor interactions and reducing the total number of experiments required [25]. The method operates by constructing a geometric figure (a simplex) defined by n+1 points in an n-dimensional factor space, with each point representing a specific combination of factor levels.

Two primary variants find application in chromatographic method development: the fixed-size simplex and the variable-size (or modified) simplex. The latter incorporates expansion and contraction rules that allow the simplex to adapt its size based on local topography of the response surface, accelerating convergence toward the optimum [1]. For functions with several variables where partial derivatives are unobtainable, the simplex method represents the best optimization option among sequential methods [25].

Quantitative Performance Data

The effectiveness of simplex optimization in chromatographic applications is demonstrated through multiple case studies reporting significant improvements in separation efficiency and analysis time. The following table summarizes key performance metrics from published applications:

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Simplex Optimization in HPLC Method Development

| Application Domain | Key Parameters Optimized | Performance Improvement | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phenolic acids separation in wastewater | Linear gradient stages, furnace temperature | Analysis time reduced from 69 to 40 minutes | [26] |

| Capsaicinoid compounds determination | Mobile phase composition, flow rate, column temperature | Achieved separation in 11 minutes with 63.7% methanol at 43.5°C | [27] |

| Neutral organic solutes separation | Mobile phase composition in constrained mixture space | Achieved optimal separation using overall desirability function | [3] |

| Artificial Neural Network optimization for gamma-ray spectrometry | Learning rate, momentum, epochs, hidden nodes | Significantly faster convergence compared to trial-and-error approach | [28] |

Beyond these specific applications, simplex optimization has demonstrated value in scenarios where traditional optimization approaches prove inadequate. For instance, in the optimization of artificial neural networks applied to gamma-ray spectrometry, the simplex method achieved significantly faster convergence compared to conventional "trial and error" approaches, which often exhibit slow convergence due to parameter interdependencies [28].

Experimental Protocols

Sequential Simplex Optimization for HPLC Method Development

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for HPLC Method Development

| Reagent/Material | Function in Optimization | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| C18 Reverse-Phase Column | Stationary phase for compound separation | Phenolic acids, basic pharmaceuticals |

| Methanol, Acetonitrile, 2-Propanol | Organic modifiers for mobile phase | Neutral organic solutes, capsaicinoids |

| Buffer Solutions (various pH) | Mobile phase component controlling ionization | Basic pharmaceuticals, phenolic acids |

| Reference Standards (Target Analytes) | System performance assessment | Capsaicinoids, phenolic acids, pharmaceuticals |

Protocol 1: Initial Scouting Phase

Define Factors and Responses: Select critical chromatographic parameters to optimize (typically 2-4 factors), such as mobile phase composition, gradient profile, flow rate, or column temperature. Define a chromatographic response function (CRF) that quantifies separation quality, incorporating factors such as resolution, analysis time, and peak symmetry [26] [1].

Establish Factor Boundaries: Set practical constraints for each factor based on instrumental capabilities and methodological requirements (e.g., methanol content in mobile phase: 50-80%, temperature: 20-50°C, flow rate: 0.8-1.5 mL/min) [27].

Construct Initial Simplex: Design n+1 initial experiments for n factors. For a 2-factor optimization, this requires 3 initial experiments arranged in a triangular pattern within the factor space [25] [1].

Run Experiments and Evaluate Responses: Execute chromatographic runs for each vertex of the initial simplex. Calculate the CRF for each experiment.

Protocol 2: Iterative Optimization Phase

Identify Response Extremes: After each set of experiments, identify the vertex with the worst CRF (least desirable response).

Reflect Worst Point: Generate a new vertex by reflecting the worst point through the centroid of the remaining points.

Evaluate New Vertex: Run the experiment corresponding to the new vertex and calculate its CRF.

Apply Expansion/Contraction Rules:

Implement Termination Criteria: Continue iterations until the simplex circles in a small region or the response meets predefined criteria. A recommended stop criterion involves continuous comparison of the attained chromatographic response function with that predicted [1].

For complex separations with multiple competing objectives, implement an overall desirability function that incorporates both chromatographic response function and total analysis time [3]. This approach is particularly valuable when developing methods that must balance separation quality with throughput requirements.

Workflow and Decision Pathways

The following diagram illustrates the complete sequential simplex optimization workflow with decision pathways for reflection, expansion, and contraction operations:

Diagram 1: Sequential Simplex Optimization Workflow

Technical Discussion

Advantages Over Alternative Methods

The simplex method offers distinct advantages that make it particularly suitable for initial method scouting in chromatographic development:

Simplicity of Implementation: The algorithm requires no complex mathematical operations or derivative calculations, making it accessible to researchers without advanced mathematical background [25]. Most modern chromatographic data systems can implement simplex protocols with minimal programming effort.

Experimental Efficiency: By simultaneously varying all factors, simplex methods typically converge to optimal conditions with fewer experiments compared to univariate approaches. This reduces solvent consumption, instrument time, and analyst effort [26] [25].

Robustness to Noisy Responses: Unlike gradient-based methods that can be misled by experimental variability, the simplex approach relies on comparative rankings of responses rather than precise numerical values, making it tolerant to typical analytical variation.

Adaptability to Constraints: Practical chromatographic optimization often involves constrained factor spaces (e.g., mobile phase component percentages must sum to 100%). The sequential simplex can be effectively implemented in such constrained spaces through appropriate boundary handling mechanisms [3].

Practical Considerations for Implementation

Successful application of simplex optimization requires attention to several practical aspects:

Scale Selection: Proper scaling of factors is critical to ensure the simplex is not distorted. Factors should be normalized or transformed to comparable ranges to prevent one parameter from dominating the search [25].

Initial Simplex Design: The size and orientation of the initial simplex significantly impact performance. A relatively large simplex is preferable for initial scouting to promote rapid exploration of the factor space.

Response Function Design: The chromatographic response function should comprehensively capture separation quality. A well-designed CRF typically incorporates resolution metrics, analysis time, and peak symmetry weighted according to methodological priorities [26] [1].

Simplex optimization provides chromatographers with a powerful tool for efficient method development, particularly during the initial scouting phase where rapid convergence to promising regions of the factor space is essential. The method's simplicity, experimental efficiency, and robust performance make it particularly valuable for researchers developing liquid chromatographic methods for pharmaceutical applications. By implementing the protocols and considerations outlined in this application note, scientists can systematically leverage simplex optimization to accelerate method development while maintaining scientific rigor.

From Theory to Practice: Implementing Simplex Optimization for Complex Pharmaceutical and Natural Product Separations

Simplex optimization is a powerful experimental design strategy used for method development and parameter optimization in liquid chromatography (LC). Unlike traditional one-factor-at-a-time (OFAT) approaches, the simplex method systematically varies multiple parameters simultaneously to rapidly converge toward optimum conditions [20]. This efficiency makes it particularly valuable for optimizing critical LC parameters such as mobile phase composition, column temperature, and flow rate, which significantly influence chromatographic performance including resolution, peak symmetry, and analysis time [20] [29].

This application note provides a detailed, practical workflow for designing an initial simplex and planning the experimental sequence, framed within the broader context of LC parameter optimization for drug development and analytical research. The protocols are designed to be implemented by researchers and scientists to improve the robustness and efficiency of their chromatographic method development.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Materials and Reagents

The following table details key reagents, materials, and instrumental components essential for executing simplex optimization of liquid chromatographic parameters.

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Simplex Optimization in Liquid Chromatography

| Item Name | Function/Application | Critical Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| C-8 Reverse Phase Column | Stationary phase for chromatographic separation of analytes [20] | 15 cm length, 4.6 mm internal diameter [20] |

| HPLC-Grade Methanol | Organic modifier in mobile phase; critical parameter for optimization [20] | High purity to minimize baseline noise and ghost peaks |

| Ultrapure Water | Aqueous component of mobile phase | 18.2 MΩ·cm resistivity |

| Analytical Reference Standards | Target analytes for method development and optimization | Capsaicinoid compounds or other relevant analytes of interest [20] |

| UV/Vis Detector | Detection of eluted analytes | Set to appropriate wavelength for target compounds |

| Chromatographic Data System | Data acquisition, peak integration, and calculation of response functions | Capable of recording at high data acquisition rates |

Core Experimental Protocol

Defining the Optimization Objective and Chromatographic Response Function (CRF)

The first critical step is to define a quantitative Chromatographic Response Function (CRF) that mathematically represents a successful separation. The CRF should incorporate multiple performance criteria into a single value to be maximized.

- Identify Critical Resolution Goals: Determine the minimum required resolution (e.g., Rs > 1.5) between the most critical peak pair [20].

- Formulate the CRF: A typical CRF might combine factors for analysis time, resolution, and peak symmetry. An example function is:

CRF = Σ(Resolution) + (Penalty for long retention times) + (Peak Symmetry Factor) - Validate the CRF: Ensure the function adequately reflects separation quality by testing with a few preliminary chromatographic runs.

Selecting Factors and Defining the Simplex Boundaries

Choose the independent LC variables (factors) to be optimized and define their operational boundaries based on instrument capabilities and method requirements.

- Factor Selection: Common factors for reversed-phase LC include:

- Set Boundaries: Define the minimum and maximum value for each selected factor to create a constrained experimental domain.

Constructing the Initial Simplex

The initial simplex is a geometric figure with n+1 vertices, where n is the number of factors being optimized. For a two-factor optimization, the simplex is a triangle.

- Establish the Starting Vertex: This is often the current or best-known method conditions. For example:

- Factor A (%Methanol): 60%

- Factor B (Flow Rate): 1.0 mL/min

- Factor C (Temperature): 35 °C

- Calculate Remaining Vertices: The other vertices are calculated based on the step size for each factor. The table below provides an example set of initial vertices for a two-factor simplex optimizing %Methanol and Temperature.

Table 2: Example Experimental Vertices for a Two-Factor Simplex Optimization

| Vertex Name | % Methanol | Temperature (°C) | CRF Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| W (Worst) | 60.0 | 35.0 | 4.2 |

| N (Next Best) | 63.7 | 43.5 | To be determined |

| B (Best) | 65.0 | 40.0 | 7.8 |

Executing the Experimental Sequence and Simplex Evolution

The workflow for running experiments and evolving the simplex is a sequential, iterative process. The following diagram visualizes the logical flow and decision points of this sequence.

Diagram 1: Simplex Optimization Experimental Workflow

The experimental sequence, visualized in Diagram 1, follows these steps:

- Run Initial Experiments: Perform the LC analysis at each vertex of the initial simplex (Table 2) in random order to minimize systematic error.

- Calculate and Rank: Calculate the CRF for each vertex and rank them from best (B) to worst (W).

- Generate New Vertex:

- Reflection: Reflect the worst vertex (W) through the centroid of the remaining vertices to generate a new vertex (R). The centroid is the average coordinates of all vertices except W.

- Evaluate R: Run the experiment at R and calculate its CRF.

- Decision Logic:

- If R is the new Best, perform Expansion to create vertex E further along the same direction. Replace W with E.

- If R is better than W but not the best, replace W with R.

- If R is worse than W, perform Contraction to create a new vertex C between the centroid and W. Replace W with C.

- Check Convergence: The optimization is terminated when the simplex has converged on an optimum. Criteria for convergence include:

- The standard deviation of the CRF values for all vertices falls below a pre-defined threshold (e.g., < 2%).

- The simplex size becomes smaller than a specified value.

- A predetermined number of experiments have been conducted.

This protocol provides a structured, step-by-step workflow for applying simplex optimization to liquid chromatography parameters. By systematically exploring the multi-dimensional parameter space, researchers can efficiently identify optimal chromatographic conditions, saving time and resources compared to univariate approaches. The outlined procedure—from defining a robust CRF to executing the iterative experimental sequence—ensures a scientifically rigorous path to a robust analytical method, directly supporting critical activities in drug development and scientific research.

In the development of therapeutic oligonucleotides, purification is a critical step to ensure the removal of failure sequences and impurities, guaranteeing the safety and efficacy of the final product [30] [31]. Anion exchange chromatography (AEX) and Ion-Pair Reversed-Phase HPLC (IP-RP-HPLC) are two dominant techniques for achieving high-purity separations [32] [31]. This application note details a structured approach, framed within the context of simplex optimization research, for developing and scaling up gradient elution methods for the purification of a model 20-mer oligonucleotide.

The sequential simplex method is a powerful optimization technique that uses a geometric algorithm to systematically vary multiple chromatographic parameters simultaneously to find the optimal response, such as a chromatographic function balancing resolution and analysis time [20] [6]. While this case study focuses on the practical outcomes, the experimental design and optimization philosophy are grounded in this rigorous chemometric approach.

Experimental Design and Workflow

The optimization and scale-up process follows a logical progression from initial analytical separation to preparative purification, as outlined in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Overall workflow for oligonucleotide purification method development and scale-up. The process begins with an analytical separation using a standard HFIP-based method and transitions to a more practical TEAA-based method before scaling up to preparative purification [33].

Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

Successful purification relies on the selection of appropriate stationary phases and mobile phases. Key materials used in this study are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Essential Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

| Item | Function/Description | Example/Supplier |

|---|---|---|

| XBridge Oligonucleotide BEH C18 Column | Batch-tested C18 stationary phase specially selected for reproducible oligonucleotide separation under ion-pairing conditions [33]. | Waters (p/n: 186003953 for 4.6 x 50 mm) [33] |

| WorkBeads 40Q AEX Resin | Strong anion exchange resin (45-µm bead) with high dynamic binding capacity, suitable for process-scale purification [30]. | Bio-Works [30] |

| Triethylamine/Hexafluoroisopropanol (TEA/HFIP) | Gold-standard ion-pairing mobile phase for analytical LC-MS, providing excellent peak shapes [33]. | - |

| Triethylammonium Acetate (TEAA) | Volatile, HFIP-alternative ion-pairing reagent; reduces cost and hazard for preparative scale, easily removed post-purification [33]. | - |

| Hexylammonium Acetate (HAA) | Alternative ion-pairing reagent with longer alkyl chain; can enhance retention but may be less volatile [33]. | - |

| Crude 20-mer Oligonucleotide | Model compound for method development and scale-up (Sequence: 5’-G-C-C-T-C-A-G-T-C-T-G-C-T-T-C-C-A-C-C-T-3’) [33]. | Oligo Factory [33] |

Method Optimization and Scale-up

Initial Analytical Method and Mobile Phase Optimization

The initial separation of the 20-mer oligonucleotide was achieved using a UPLC system with a TEA/HFIP mobile phase and a column temperature of 60°C to eliminate secondary structure [33]. While this provides excellent analytical performance, HFIP is costly and hazardous for large-scale use.

To address this, a new method was developed using 100 mM triethylammonium acetate (TEAA) at pH 7.0 as the aqueous mobile phase and acetonitrile as the organic modifier. This volatile buffer system is more suitable for preparative work as it is safer and can be easily removed via lyophilization after fraction collection [33]. The column temperature was also reduced to 25°C for practical preparative operation.

Gradient Elution Optimization for AEX Purification

In AEX, the gradient profile is critical for separating oligonucleotides based on their charge, which correlates with length. Figure 2 illustrates the key steps and critical parameters for developing an AEX purification method.