Simplex vs Design of Experiments (DOE): A Strategic Guide for Pharmaceutical Optimization

This article provides a comparative analysis of Simplex and Design of Experiments (DOE) methodologies for researchers and professionals in drug development.

Simplex vs Design of Experiments (DOE): A Strategic Guide for Pharmaceutical Optimization

Abstract

This article provides a comparative analysis of Simplex and Design of Experiments (DOE) methodologies for researchers and professionals in drug development. It explores the foundational principles of both approaches, detailing their specific applications in process optimization, formulation, and validation. The content offers practical guidance on selecting the appropriate method based on project goals, prior knowledge, and resource constraints, and discusses how these strategies enhance efficiency, robustness, and regulatory compliance in biomedical research.

Understanding the Core Principles: Simplex and DOE in Scientific Research

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent/Equipment | Function in Experimental Context |

|---|---|

| Inline FT-IR Spectrometer | Enables real-time reaction monitoring and conversion calculation in continuous flow systems [1]. |

| Microreactor System | Provides a controlled, automated environment for efficient screening of reaction parameters with high reproducibility [1]. |

| Ethanol Solvent | Used for the extraction of polyphenols and antioxidant compounds from plant material due to high efficacy [2]. |

| Syringe Pumps | Allow precise dosage and control of reactant flow rates in automated experimental setups [1]. |

| Robotic Automation | Facilitates high-throughput studies, enabling the simultaneous evaluation of numerous experimental conditions [3]. |

In the realm of scientific research and process optimization, two methodologies stand out for their systematic approach to experimentation: Design of Experiments (DOE) and the Simplex method. DOE is a branch of applied statistics that deals with planning, conducting, analyzing, and interpreting controlled tests to evaluate the factors that control the value of a parameter or group of parameters [4]. It is a powerful data collection and analysis tool that allows multiple input factors to be manipulated simultaneously to determine their effect on a desired output, thereby identifying important interactions that might otherwise be missed [4] [5].

The core of this analysis contrasts DOE with the "One Factor At a Time" (OFAT) approach, which is inefficient and fails to capture interactions between factors [4] [5]. Beyond OFAT, more advanced optimization algorithms exist, notably the Simplex method. The broader research context pits the model-building, pre-planned framework of DOE against the iterative, model-free search characteristic of the Simplex algorithm [1]. This guide provides an objective comparison of these methodologies, underpinned by experimental data, to inform the choices of researchers and development professionals in drug development and related fields.

Core Principles and Key Methodologies

The Fundamental Framework of Design of Experiments (DOE)

DOE is a systematic approach used by scientists and engineers to study the effects of different inputs on a process and its outputs [5]. Its power lies in its ability to efficiently characterize an experimental space and build a predictive model from a structured set of runs.

Key Concepts: The methodology is built upon several foundational principles established by R.A. Fisher [4] [6]:

- Randomization: The order in which experimental trials are performed is randomized to eliminate the effects of unknown or uncontrolled variables [4].

- Replication: Repetition of a complete experimental treatment, including the setup, to help estimate the true effect of treatments and understand sources of variation [4].

- Blocking: A technique to restrict randomization by grouping experimental units that are similar to one another, thereby reducing known but irrelevant sources of variation [4] [6].

Factorial Designs: A common DOE approach where multiple factors are varied simultaneously across their levels. A full factorial design studies the response of every combination of factors and factor levels [4]. For

nfactors, a 2-level full factorial requires2^nexperimental runs [4]. This allows for the estimation of both main effects and interaction effects between factors.

The Iterative Search of the Simplex Method

The Simplex method, particularly the Nelder-Mead variant, is an iterative optimization algorithm that operates without building an explicit model of the entire response surface [1]. Instead, it uses a geometric shape (a simplex) to navigate the experimental space.

- Core Mechanism: The algorithm starts with an initial simplex defined by

n+1vertices in ann-dimensional factor space. It then iteratively evaluates the response at each vertex, moving away from poor-performing regions and towards the optimum by reflecting, expanding, or contracting the simplex [1] [3]. - Model-Free Approach: A key differentiator from DOE is that the Simplex method does not require a pre-defined model. It uses real-time experimental feedback to guide its search, making it suitable for systems where a predictive model is difficult to establish a priori [1].

- Grid-Compatible Variant: For high-throughput applications common in early bioprocess development, a gridded Simplex variant has been developed. This variant is designed to operate on coarsely gridded data, preprocessing the search space and handling missing data points to rapidly identify optima [3].

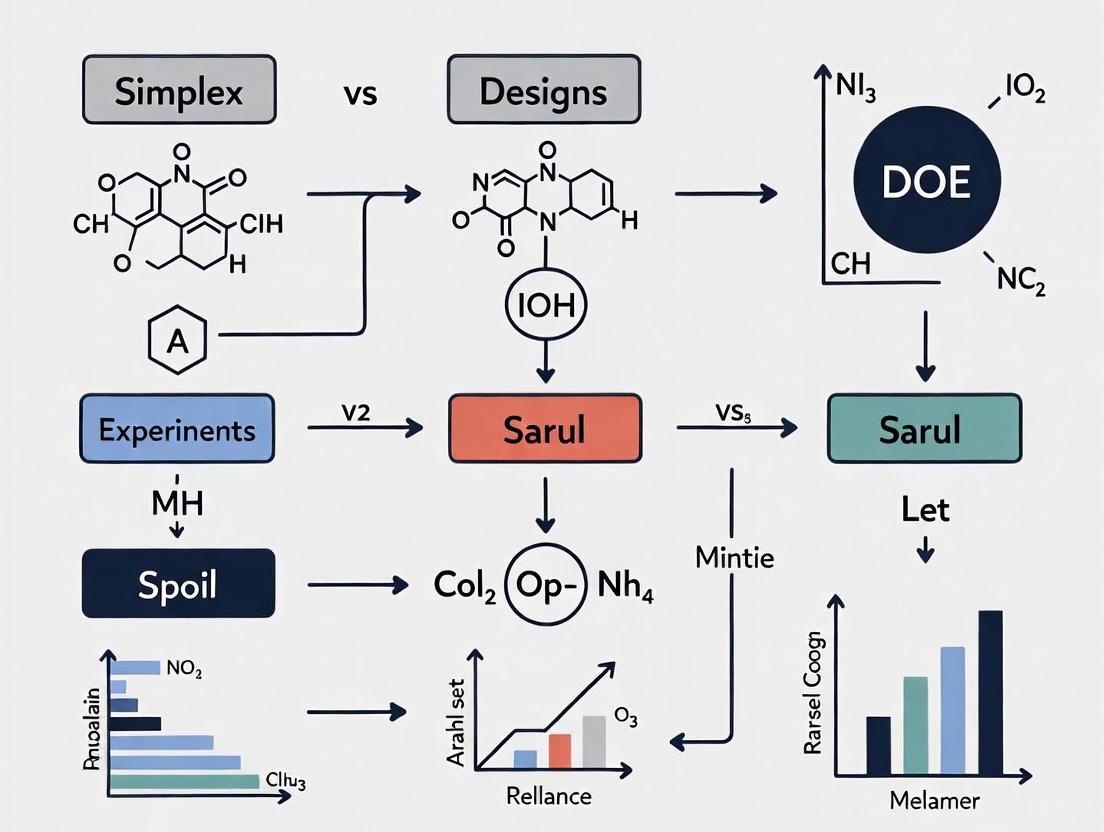

Visualizing the Methodological Workflows

The fundamental difference between the two approaches is their workflow structure: DOE follows a comprehensive plan-build-analyze sequence, while Simplex employs an iterative evaluate-and-adapt cycle.

Comparative Experimental Analysis: DOE vs. Simplex

Performance in Chemical Synthesis Optimization

A direct comparison was conducted in the optimization of an imine synthesis reaction in a microreactor system, with the goal of maximizing product yield. The table below summarizes the performance of a modified Simplex algorithm versus a model-free DOE approach [1].

Table 1: Performance in Imine Synthesis Optimization [1]

| Optimization Method | Key Characteristics | Number of Experiments to Converge | Final Yield Achieved | Ability to React to Process Disturbances |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Design of Experiments (DOE) | Model-based, broad screening of parameter space. | Pre-determined set of runs. | High yield. | Limited; model must be re-built if process changes. |

| Simplex Algorithm | Model-free, iterative real-time optimization. | Fewer experiments required. | High yield (comparable to DOE). | High; can dynamically adjust to disturbances. |

The study concluded that both methods were capable of identifying optimal reaction conditions that maximized product yield [1]. The Simplex algorithm demonstrated a particular advantage in its ability to be modified for real-time response to process disturbances, a valuable feature for industrial applications where fluctuations in raw materials or temperature control can occur [1].

Performance in Multi-Objective Bioprocess Development

The gridded Simplex method was evaluated against a DOE approach in three high-throughput chromatography case studies for early bioprocess development. The goal was multi-objective optimization, simultaneously balancing yield, residual host cell DNA, and host cell protein (HCP) content [3].

Table 2: Multi-Objective Optimization in Bioprocessing [3]

| Optimization Method | Modeling Approach | Success in Locating Pareto Optima | Computational Time | Dependency on Starting Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Design of Experiments (DOE) | Quartic (4th order) regression models with desirability functions. | Low success rate, despite high-order models. | Not Specified | N/A (Pre-planned design) |

| Grid Compatible Simplex | Model-free, used desirability functions directly. | Highly successful in delivering Pareto-optimal conditions. | Sub-minute computations. | Low dependency. |

The study found that the DOE approach, even with complex quartic models, struggled to reliably identify optimal conditions across all responses. In contrast, the Simplex method consistently located operating conditions belonging to the Pareto set (conditions where no objective can be improved without worsening another) and offered a balanced, superior performance [3].

Application in Herbal Formulation Development

A Simplex Lattice Mixture Design, a specific type of DOE for formulations, was used to optimize an antioxidant blend from three plants: celery, coriander, and parsley [2]. This showcases DOE's strength in scenarios where the components are proportions of a mixture.

Table 3: Optimal Formulation for Antioxidant Activity [2]

| Plant Component | Proportion in Optimal Mixture | Key Antioxidant Metric Contributed |

|---|---|---|

| Apium graveolens L. (Celery) | 0.611 (61.1%) | Contributes to overall synergistic blend. |

| Coriandrum sativum L. (Coriander) | 0.289 (28.9%) | High total antioxidant capacity (TAC). |

| Petroselinum crispum M. (Parsley) | 0.100 (10.0%) | High total polyphenol content (TPC). |

| Optimal Blend Result | DPPH: 56.21%, TAC: 72.74 mg AA/g, TPC: 21.98 mg GA/g |

The ANOVA analysis confirmed that the model was statistically significant, with high determination coefficients (R² up to 97%), successfully capturing the synergistic effects of the plant combination to achieve higher antioxidant activity than the individual components [2].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Basic Two-Factor Full Factorial DOE

This protocol outlines the steps for a foundational DOE, as exemplified in the ASQ resources [4].

- Acquire Understanding: Create a process map and consult with subject matter experts to fully understand the inputs and outputs. Determine an appropriate, quantifiable measure for the output response [4].

- Define Factors and Levels: Select the input factors to investigate and determine the extreme but realistic high (

+1) and low (-1) levels for each. For example, Temperature (100°C and 200°C) and Pressure (50 psi and 100 psi) [4]. - Create Design Matrix: Construct a matrix showing all possible combinations of the factor levels. For 2 factors, this requires 4 experimental runs (

2^2). The design matrix with coded units is shown below [4]. - Execute Experiments Randomly: Conduct the experimental runs in a randomized order to eliminate the effect of confounding variables [4].

- Analyze Effects: Calculate the main effect of each factor. For example, the effect of Temperature is the average response at high Temperature minus the average response at low Temperature, across all levels of Pressure:

Effect_Temp = [(Y_3 + Y_4)/2] - [(Y_1 + Y_2)/2][4].

Table 4: 2-Factor Full Factorial Design Matrix [4]

| Experiment # | Input A (Temp.) | Input B (Pressure) | Response (Strength) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | -1 (100°C) | -1 (50 psi) | Y₁ (21 lbs) |

| 2 | -1 (100°C) | +1 (100 psi) | Y₂ (42 lbs) |

| 3 | +1 (200°C) | -1 (50 psi) | Y₃ (51 lbs) |

| 4 | +1 (200°C) | +1 (100 psi) | Y₄ (57 lbs) |

Protocol: Self-Optimizing Simplex in Continuous Flow

This protocol is derived from the work on autonomous optimization of imine synthesis in a microreactor system [1].

- Setup Automated Platform: Assemble a system integrating a microreactor, automated syringe pumps for reagent delivery, a temperature control unit, and real-time analytics (e.g., inline FT-IR spectroscopy). The system must be controlled by software that can execute the optimization algorithm [1].

- Define Objective Function: Program the objective to be optimized (e.g., yield of product

3calculated from the IR band at 1620-1660 cm⁻¹) into the control software [1]. - Initialize Simplex: Define the initial simplex in the factor space (e.g., using residence time and temperature as factors). For

nfactors, this requiresn+1initial experiments [1]. - Run Iterative Optimization: The software controls the iterative loop:

- The system conducts experiments at the current simplex vertices.

- The control software calculates the objective function (yield) for each vertex from the real-time analytical data.

- Based on the values (e.g., worst, best), the algorithm determines and executes the next experiment (reflection, expansion, contraction).

- The simplex moves and shrinks, converging towards the optimal conditions [1].

- Validate Optimum: Once a stopping condition is met (e.g., minimal improvement), run a confirmation experiment at the predicted optimum to validate the result.

Logical Relationship and Selection Criteria

The choice between DOE and Simplex is not a matter of which is universally better, but which is more appropriate for a given research goal and context. The following diagram outlines the decision-making logic.

The systematic comparison of Design of Experiments and the Simplex method reveals a clear, complementary relationship. DOE is the superior tool for initial process understanding and model building, providing a comprehensive map of factor effects and interactions from a pre-planned set of experiments. In contrast, the Simplex method excels at rapid, model-free local optimization, especially in automated systems where it can dynamically respond to changes. The choice for researchers, particularly in drug development, hinges on the primary objective: deep system characterization favors DOE, while efficient convergence to an optimal operating point favors Simplex. As evidenced in bioprocessing and chemical synthesis, the strategic application of each method, and sometimes their hybrid use, can significantly accelerate development and enhance process robustness.

In the rigorous field of scientific research, particularly within drug development and bioprocessing, the Design of Experiments (DOE) provides a structured framework for efficiently acquiring knowledge. Three foundational principles form the bedrock of a sound experimental design: randomization, replication, and blocking [7]. These principles are designed to manage sources of variation, control for bias, and provide a robust estimate of experimental error, thereby ensuring the validity and reliability of the conclusions drawn.

Understanding these principles is also critical for evaluating different experimental approaches. This guide frames the discussion within a broader thesis comparing traditional DOE methodologies with alternative algorithms, such as the Hybrid Experimental Simplex Algorithm (HESA), which has emerged as a valuable tool for identifying bioprocess "sweet spots" [8]. We will objectively compare the application of these core principles in both conventional DOE and the simplex-based approach, providing experimental data and protocols to illustrate their performance in real-world scenarios.

Unpacking the Core Principles

The effective implementation of randomization, replication, and blocking is what separates conclusive experiments from mere data collection.

Randomization

Randomization is the deliberate process of assigning experimental treatments to units through a random mechanism [7]. Its primary role is to eliminate systematic bias and to validate the assumption of independent errors, which is foundational for most statistical analyses.

- Purpose and Function: By randomly allocating treatments, the investigator ensures that any unknown, lurking variables or uncontrolled sources of variation are distributed independently of the treatment effects. This prevents biases, such as those that could occur if treatments were applied in a specific temporal or spatial order. A classic example is confounding, where a drug's effect is indistinguishable from a patient's gender if the drug is given only to males and the placebo only to females [7].

- Consequence of Neglect: Failure to randomize can lead to confounded results, where apparent treatment effects may actually be caused by other, unrecorded factors, rendering the study's conclusions invalid [7].

Replication

Replication refers to the repetition of an experimental treatment under the same conditions. It is fundamentally different from repeated measurements on the same experimental unit.

- Purpose and Function: Replication provides a means of estimating the inherent random error or "noise" in the experimental system. With an estimate of this error, researchers can assess whether observed differences between treatments are statistically significant or likely due to random chance. The precision of the estimated effect of a treatment increases with the number of replications, as the standard error of the mean decreases with increasing sample size (n), following the formula √(s²/n) [7].

- Consequence of Neglect: Without sufficient replication, there is no reliable way to quantify uncertainty. This makes it impossible to determine the precision of estimates or to perform meaningful statistical tests, leaving the researcher unable to judge the practical significance of the findings.

Blocking

Blocking is a technique used to increase the precision of an experiment by accounting for nuisance factors—known sources of variability that are not of primary interest.

- Purpose and Function: A "block" is a group of experimental units that are homogeneous. By grouping similar units together and then randomizing treatments within each block, the variability between blocks can be isolated and removed from the experimental error. Common blocking factors include batches of raw material, different days of experimentation, or demographic characteristics like age and gender in clinical studies [7].

- Consequence of Neglect: If not accounted for through blocking, nuisance factors can contribute significantly to the overall error variance. This inflates the random error, making it more difficult to detect significant treatment effects when they truly exist.

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for applying these three principles in a sequential manner to design a robust experiment.

Case Study: Simplex vs. DOE in Bioprocessing

To test the practical application of these principles, we examine a comparative study between a conventional Response Surface Methodology (RSM) DOE and the Hybrid Experimental Simplex Algorithm (HESA) in a bioprocessing context.

Experimental Protocols

Objective: To identify the operating "sweet spot" for the binding of a green fluorescent protein (GFP) to a weak anion exchange resin [8].

Methodology:

- Factor Selection: Two critical process parameters (CPPs) were identified: pH and salt concentration.

- Experimental Setup: The study was conducted in a 96-well filter plate format, a common high-throughput screening platform. GFP was isolated from Escherichia coli homogenate.

- Response Measurement: The primary response variable was the measured binding capacity of the resin for the GFP.

- Comparison Framework: Both the established HESA and a conventional RSM-based DOE were deployed to explore the factor space and define the sweet spot. The experimental cost, defined by the total number of experimental runs required, was held comparable between the two methods to allow for a fair comparison [8].

Key Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details the essential materials and reagents used in the featured bioprocessing experiment.

| Reagent/Material | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP) | The target molecule of interest, used to study binding efficiency under different conditions [8]. |

| Escherichia coli Homogenate | The source material from which the GFP is isolated, representing a typical complex biological feedstock [8]. |

| Weak Anion Exchange Resin | The chromatographic medium whose binding capacity for GFP is being optimized [8]. |

| 96-Well Filter Plate | A high-throughput platform enabling parallel processing of multiple experimental conditions [8]. |

Performance Comparison and Data

The following table summarizes the quantitative results from the case study, comparing the performance of HESA and a conventional DOE approach.

| Performance Metric | Hybrid Experimental Simplex Algorithm (HESA) | Conventional RSM DOE |

|---|---|---|

| Sweet Spot Definition | Better at delivering valuable information on the size, shape, and location of operating sweet spots [8]. | Provided a less defined characterization of the sweet spot region in comparison [8]. |

| Experimental Cost | Comparable number of experimental runs required [8]. | Comparable number of experimental runs required [8]. |

| Methodology | An adaptive, sequential process that moves towards optimal conditions based on previous results [8]. | A pre-planned, static set of experiments based on a statistical design [7]. |

| Primary Strength | Efficiently scouts a large factor space to find a subset of optimal conditions; well-suited for initial process development [8]. | Provides a comprehensive model of the response surface across the entire design space; ideal for in-depth process understanding [7]. |

The workflow for the HESA, which underpinned its performance in this study, is shown below.

Discussion: Principles in Different Methodological Contexts

The case study data reveals how core DOE principles are applied differently across methodologies. Conventional DOE embeds replication and blocking directly into its pre-planned design to explicitly quantify error and control nuisance factors [7]. Randomization is critical to avoid confounding.

In contrast, the HESA is an adaptive, sequential method. Its strength lies in its efficient movement through the factor space rather than building a comprehensive model of it. While it may not use replication and blocking in the same formalized way as traditional DOE, its iterative nature provides a different form of robustness. The constant generation and testing of new experimental conditions based on previous results allow it to converge on a well-defined sweet spot with comparable experimental effort [8]. This makes HESA a powerful scouting tool, though it may be less suited for generating the detailed, predictive models that RSM-DOE provides. The choice between them hinges on the experimental goal: rapid identification of optimal conditions versus comprehensive process characterization.

In the broader context of research comparing simplex designs with Design of Experiments (DOE) methodologies, three designs frequently serve as fundamental building blocks for experimental campaigns: Full Factorial, Fractional Factorial, and Response Surface Methodology (RSM). These designs represent different approaches to balancing experimental effort with information gain. Full Factorial designs provide comprehensive data on all possible factor combinations but at significant cost when factors are numerous. Fractional Factorial designs offer a practical alternative for screening large numbers of factors with reduced experimental runs by strategically confounding higher-order interactions. Response Surface Methodology represents an advanced sequential approach for modeling complex relationships and locating optimal process conditions, typically building upon information gained from initial factorial experiments. Understanding the capabilities, limitations, and appropriate applications of each design is crucial for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to optimize experimental efficiency and analytical depth in their investigative workflows.

Full Factorial Designs

Fundamental Principles and Applications

Full factorial designs investigate all possible combinations of factors and their levels, enabling researchers to determine both main effects and all orders of interactions between factors [9]. This comprehensive approach ensures that no potential interaction is overlooked, providing a complete picture of the system under investigation [10]. The number of experimental runs required for a full factorial design grows exponentially with the number of factors (2^k for a 2-level design with k factors), making it most suitable for experiments with a limited number of factors (typically 4 or fewer) or when the experimental runs are inexpensive to execute [9] [11].

Full factorial designs are particularly valuable in drug development for formulation optimization, process characterization, and understanding complex interactions between factors such as excipient concentrations, drug particle size, and processing conditions that affect bioavailability, stability, and release profiles [10]. The methodology provides robust data for building predictive models that can accurately forecast system behavior across the entire experimental space.

Experimental Protocol and Design Considerations

Key components of a full factorial experimental protocol:

- Factor Selection: Identify independent variables (factors) to be investigated, classifying them as numerical (e.g., temperature, pressure) or categorical (e.g., material type, production method) [10].

- Level Determination: Establish appropriate low and high levels for each factor based on prior knowledge or preliminary experiments [12].

- Randomization: Randomly assign the order of experimental runs to mitigate the effects of extraneous variables and ensure statistical validity [12] [10].

- Replication: Repeat critical experimental runs to estimate experimental error and improve reliability of effect estimates [12].

- Center Points: Include center points (mid-level values for all factors) to detect curvature in the response surface and estimate experimental error [9] [12] [11].

The following diagram illustrates a typical workflow for planning and executing a full factorial experiment:

Statistical Analysis and Interpretation

Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) serves as the primary statistical tool for analyzing full factorial experiments, determining the significance of main effects and interaction effects on the response variable [10]. ANOVA partitions the total variability in the data into components attributable to each factor and their interactions, enabling researchers to identify the most influential factors and their relationships. Regression analysis complements ANOVA by fitting a mathematical model to the experimental data, relating the response variable to the independent variables and their interactions [10]. This model can predict the response for any factor level combination within the experimental region and facilitate optimization through techniques like response surface analysis.

Fractional Factorial Designs

Fundamental Principles and Applications

Fractional factorial designs (FFDs) represent a strategic subset of full factorial designs that test only a carefully selected fraction of the possible factor combinations [13]. This approach significantly reduces the number of experimental runs required while still providing information about main effects and lower-order interactions [9] [11]. The methodology is grounded in the sparsity-of-effects principle, which assumes that higher-order interactions (typically involving three or more factors) are negligible compared to main effects and two-factor interactions [13]. This rational reduction in experimental effort makes FFDs particularly valuable for screening a large number of factors (typically 5 or more) to identify the most influential ones for further investigation [9] [13].

In pharmaceutical development, FFDs efficiently identify critical process parameters (CPPs) and critical material attributes (CMAs) from a large set of potential factors during early-stage process development [13]. This enables researchers to focus resources on optimizing the most impactful variables in subsequent experimentation. The design notation l^(k-p) indicates a fractional factorial design where l is the number of levels, k is the number of factors, and p determines the fraction size (e.g., 2^(5-2) represents a 1/4 fraction of a two-level, five-factor design requiring only 8 runs instead of 32) [13].

Experimental Protocol and Design Considerations

Key protocol elements for fractional factorial designs:

- Design Resolution Selection: Choose an appropriate design resolution (III, IV, V, or higher) based on the desired ability to separate effects, with higher resolutions providing less confounding between effects [13].

- Generator Selection: Identify which factors will be confounded with interactions of other factors, defining the alias structure of the design [13].

- Alias Structure Evaluation: Examine which effects are confounded with each other and ensure the confounding pattern aligns with experimental assumptions about negligible interactions [9] [13].

- Randomization and Replication: Implement randomization to mitigate bias and include replication where possible to estimate error [10].

Resolution III designs are suitable for screening many factors when assuming two-factor interactions are negligible, while Resolution IV designs confound two-factor interactions with each other but not with main effects, and Resolution V designs allow estimation of all two-factor interactions without confounding with other two-factor interactions [13].

Understanding Aliasing and Resolution

The primary trade-off in fractional factorial designs is aliasing (or confounding), where multiple effects cannot be distinguished from each other [9] [13]. For example, in a Resolution III design, main effects are aliased with two-factor interactions, meaning that if a significant effect is detected, it could be due to either a main effect or its aliased interaction [13]. The following table summarizes key resolution levels and their interpretation:

Table: Fractional Factorial Design Resolution Levels

| Resolution | Ability | Example | Interpretation Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| III | Estimate main effects, but they may be confounded with two-factor interactions [13] | 2^(3-1) with I = ABC [13] | Main effects are clear only if interactions are negligible [13] |

| IV | Estimate main effects unconfounded by two-factor interactions; two-factor interactions may be confounded with each other [13] | 2^(4-1) with I = ABCD [13] | Safe for identifying important main effects [13] |

| V | Estimate main effects and two-factor interactions unconfounded by each other [13] | 2^(5-1) with I = ABCDE [13] | Comprehensive estimation of main effects and two-way interactions [13] |

Response Surface Methodology (RSM)

Fundamental Principles and Applications

Response Surface Methodology (RSM) comprises a collection of statistical and mathematical techniques for modeling and analyzing problems where several independent variables influence a dependent variable or response, with the goal of optimizing this response [14] [15]. Unlike factorial designs that focus primarily on factor screening, RSM aims to characterize the curvature of the response surface near the optimum conditions and identify the factor settings that produce the best possible response [9] [16]. RSM typically employs sequential experimentation, beginning with a first-order design (such as a fractional factorial) to ascend the response surface rapidly, followed by a second-order design to model curvature and locate the optimum precisely [16].

In pharmaceutical applications, RSM optimizes drug formulations for desired dissolution/release profiles, improves tableting processes to control tablet properties, and models lyophilization (freeze-drying) cycles to maximize product quality and process efficiency [14]. The methodology enables researchers to develop robust processes that remain effective despite minor variations in input variables, a critical consideration for regulatory compliance and manufacturing consistency.

Experimental Protocol and Sequential Approach

RSM follows a structured, sequential approach to optimization:

- Screening Experiments: Use fractional factorial designs to identify the most significant factors from a large set of potential variables [14] [16].

- Steepest Ascent/Descent: Conduct a series of experiments along the path of steepest ascent (for maximization) or descent (for minimization) to rapidly move toward the optimal region [16].

- Optimization Experiments: Once near the optimum, perform a response surface design (e.g., Central Composite Design or Box-Behnken) to model curvature and identify precise optimal conditions [9] [16].

The following diagram illustrates this sequential experimentation process:

Common RSM Designs and Analysis

Central Composite Design (CCD) is the most popular RSM design, consisting of a fractional factorial design (2^k-p) augmented with center points and axial (star) points that enable estimation of curvature [9] [11]. The axial points are positioned at a distance α from the center, with the value of α chosen to ensure rotatability (typically α = (2^(k-p))^(1/4) for a full factorial) [15]. Box-Behnken Design offers an alternative to CCD with fewer design points by combining two-level factorial designs with incomplete block designs, though it doesn't contain corner points and is appropriate when extreme factor combinations are impractical or hazardous [9].

RSM analysis involves fitting a second-order polynomial model to the experimental data:

y = β₀ + Σβᵢxᵢ + Σβᵢᵢxᵢ² + Σβᵢⱼxᵢxⱼ + ε

where y is the predicted response, β₀ is the constant term, βᵢ are the linear coefficients, βᵢᵢ are the quadratic coefficients, βᵢⱼ are the interaction coefficients, and ε is the random error [16]. The fitted model is then analyzed using ANOVA to assess significance, and the optimum is located analytically by solving the system of equations obtained by setting the partial derivatives equal to zero, or graphically through contour plots and 3D response surface plots [14] [16].

Comparative Analysis of DOE Designs

Direct Comparison of Key Characteristics

The following table provides a structured comparison of the three experimental designs across multiple dimensions to guide appropriate design selection:

Table: Comprehensive Comparison of Full Factorial, Fractional Factorial, and RSM Designs

| Characteristic | Full Factorial Design | Fractional Factorial Design | Response Surface Methodology (RSM) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Objective | Identify all main effects and interactions [17] [10] | Screen many factors to identify important ones [9] [13] | Model curvature and find optimal conditions [14] [16] |

| Typical DOE Stage | Screening, Refinement, and Iteration [9] | Screening [9] | Optimization [9] |

| Number of Runs | 2^k for 2-level designs [12] [11] | 2^(k-p) for 2-level designs [13] | Varies (e.g., CCD: 2^k + 2k + cp) [15] |

| Interactions Estimated | All interactions [12] [17] | Limited by aliasing structure [13] | Typically up to 2nd order (quadratics + 2FI) [16] |

| Curvature Detection | Limited (only via center points) [9] [11] | Limited (only via center points) [9] | Comprehensive curvature modeling [14] [16] |

| Key Assumptions | All effects including high-order interactions may be important [17] | Sparsity-of-effects (high-order interactions negligible) [13] | Quadratic model adequately approximates the response surface [15] |

| Main Limitations | Run number grows exponentially with factors [9] [10] | Effects are confounded (aliased) [9] [13] | Requires prior knowledge of important factors [16] |

Strategic Selection Guidelines

Choosing the appropriate experimental design depends on the research objectives, resources, and current knowledge about the system:

- Use Full Factorial Designs when the number of factors is small (typically ≤4), resources permit comprehensive testing, and understanding all interactions is critical [9] [10].

- Use Fractional Factorial Designs for screening many factors (typically ≥5) with limited resources, when higher-order interactions are likely negligible, and when follow-up experiments can resolve ambiguities in aliased effects [9] [13].

- Use Response Surface Methodology when the important factors have been identified (typically through prior screening), the goal is optimization rather than screening, and curvature in the response surface is expected near the optimum [9] [16].

These designs often work together sequentially in an experimental campaign: starting with fractional factorial designs to screen numerous factors, followed by full factorial designs to study important factors and their interactions in detail, and culminating with RSM to optimize the critical factors [9] [16].

Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

The following table outlines essential materials and methodological components referenced in the experimental protocols throughout this comparison:

Table: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Methodological Components

| Item | Function/Description | Experimental Role |

|---|---|---|

| Center Points | Experimental runs where all factors are set at their mid-level values [9] [12] | Detects curvature in the response surface and provides pure error estimate [9] [12] |

| Coded Variables | Factors transformed to a common scale (typically -1, 0, +1) [12] [16] | Eliminates scale dependence, improves model computation, and facilitates interpretation [14] |

| Randomization Schedule | A randomly determined sequence for conducting experimental runs [12] | Protects against effects of lurking variables and ensures statistical validity [12] [10] |

| ANOVA Framework | Statistical methodology partitioning variability into components attributable to factors and error [10] | Determines significance of main effects and interactions [10] |

| Regression Model | Mathematical relationship between factors and response variable [10] | Predicts responses for untested factor combinations and facilitates optimization [10] |

| Alias Structure | Table showing which effects are confounded in fractional factorial designs [13] | Guides interpretation of significant effects and planning of follow-up experiments [13] |

Full Factorial, Fractional Factorial, and Response Surface Methodology designs each serve distinct but complementary roles in the experimentalist's toolkit. Full factorial designs provide comprehensive information but at high cost with many factors. Fractional factorial designs offer a practical screening approach when many factors must be investigated with limited resources. Response Surface Methodology enables sophisticated modeling and optimization once critical factors are identified. Within the broader context of simplex versus DOE research, these methodologies demonstrate the power of structured experimental approaches to efficiently extract maximum information from experimental systems. The sequential application of these designs—from screening to optimization—represents a robust framework for efficient process understanding and improvement, particularly valuable in drug development where resource constraints and regulatory requirements demand both efficiency and thoroughness.

In the pursuit of optimal performance across chemical processes and analytical methods, researchers are often faced with a complex landscape of interacting variables. Two powerful strategies for navigating this landscape are the Simplex Method and Design of Experiments (DOE). While DOE is a statistically rigorous approach for mapping and modeling process behavior, the Simplex method is a model-agnostic optimization algorithm that efficiently guides experiments toward optimal conditions by making sequential, intelligent adjustments. This guide provides a detailed, objective comparison of their performance, methodologies, and ideal applications to inform researchers and development professionals.

Simplex vs. DOE: Core Concepts and Strategic Comparison

The table below contrasts the fundamental principles of the Simplex method and Design of Experiments.

| Feature | Simplex Method | Design of Experiments (DOE) |

|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Sequential, model-free search moving along edges of a geometric shape (simplex) toward an optimum [18]. | Structured, model-based approach using statistical principles to study multiple factors simultaneously [19]. |

| Experimental Approach | Iterative; each experiment's outcome dictates the next set of conditions. | Pre-planned; a fixed set of experiments is conducted based on a design matrix before analysis [19]. |

| Model Requirement | Model-agnostic; does not require a pre-defined model of the system. | Relies on building a regression model (e.g., Response Surface Methodology) to describe the system [19] [1]. |

| Primary Strength | High efficiency in converging to a local optimum with fewer initial experiments; adaptable to real-time process disturbances [1]. | Identifies factor interactions and maps the entire experimental space, providing a comprehensive process understanding [19] [1]. |

| Key Limitation | May find local, not global, optima; provides less insight into interaction effects between factors. | Can require a larger number of initial experiments, especially for a large number of factors [19] [1]. |

| Typical Applications | Real-time optimization in continuous-flow chemistry [1]. | Screening key factors and modeling processes in batch systems [1]. |

Experimental Performance Data and Case Studies

Case Study 1: Optimization of an Electroanalytical Method

A study directly compared a Fractional Factorial Design and a Simplex Optimization for developing an in-situ film electrode to detect heavy metals. The performance was judged on multiple analytical parameters simultaneously [20].

Table 1: Performance Comparison in Electroanalytical Optimization

| Optimization Method | Key Factors Optimized | Performance Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Fractional Factorial Design (Screening) | Mass concentrations of Bi(III), Sn(II), Sb(III), accumulation potential, and accumulation time [20]. | Identified the significance of individual factors, narrowing the field of variables for further study [20]. |

| Simplex Optimization | The same five factors were fine-tuned [20]. | Achieved a significant improvement in overall analytical performance (sensitivity, LOQ, linear range, accuracy, precision) compared to both initial experiments and pure film electrodes [20]. |

Case Study 2: Optimization of an Organic Synthesis in Flow

Research comparing a Modified Simplex Algorithm and DOE for optimizing an imine synthesis in a microreactor system highlighted their operational differences [1].

Table 2: Performance in Flow Chemistry Optimization

| Optimization Method | Experimental Workflow | Outcome and Performance |

|---|---|---|

| Modified Simplex Algorithm | Iterative, real-time optimization using inline FT-IR spectroscopy for feedback [1]. | Capable of real-time response to process disturbances (e.g., concentration fluctuations), compensating for them automatically. Efficiently moved toward optimum conditions [1]. |

| Design of Experiments | Pre-planned experimental space screening followed by model building [1]. | Provided a broader understanding of the experimental space and interaction effects between parameters like temperature and residence time [1]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol for a Design of Experiments (Full Factorial)

This protocol is ideal for screening factors and building a predictive model.

- Step 1: Define Inputs and Outputs: Acquire a full understanding of the inputs (factors) and outputs (responses). A process flowchart and consultation with subject matter experts are recommended [19].

- Step 2: Establish Measurement System: Determine an appropriate, variable measure for the output. Ensure the measurement system is stable and repeatable [19].

- Step 3: Create a Design Matrix: For a 2-factor experiment, investigate every combination of high (+1) and low (-1) levels for each factor. The number of experimental runs is 2^n [19].

- Example Matrix:

Experiment # Temp. Level Pressure Level 1 -1 (100°C) -1 (50 psi) 2 -1 (100°C) +1 (100 psi) 3 +1 (200°C) -1 (50 psi) 4 +1 (200°C) +1 (100 psi)

- Example Matrix:

- Step 4: Execute Experiments & Analyze Data: Conduct experiments as per the matrix. Calculate the main effect of each factor by comparing the average output at its high level versus its low level. Interaction effects can be calculated by multiplying the coded levels of the involved factors [19].

Protocol for a Simplex Optimization

This protocol is suited for efficient, sequential convergence to an optimum.

- Step 1: Define Objective Function and Variables: Establish a clear, quantifiable objective function (e.g., yield, purity). Select the independent variables to optimize (e.g., temperature, concentration) [18].

- Step 2: Initialize the Simplex: Start with n+1 experiments (vertices), where n is the number of variables. For 2 variables, this forms a triangle in the experimental space [18].

- Step 3: Evaluate and Iterate: Evaluate the objective function at each vertex. The algorithm then iteratively moves the worst-performing vertex through a series of operations:

- Reflection: Reflect the worst point away from the simplex.

- Expansion: If the new point is better, move further in that direction.

- Contraction: If the new point is worse, move a smaller distance.

- Shrinkage: If no improvement is found, shrink the entire simplex towards the best point [18].

- Step 4: Check for Convergence: The process repeats until the vertices converge upon an optimum or a predetermined termination criterion is met [18].

Workflow Visualization

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Equipment for Optimization Experiments

| Item | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| Acetate Buffer Solution | Serves as a supporting electrolyte to maintain constant pH in electroanalytical methods [20]. |

| Standard Stock Solutions | Used to prepare precise concentrations of analytes (e.g., heavy metals) and film-forming ions (e.g., Bi(III), Sn(II)) [20]. |

| Glassy Carbon Electrode (GCE) | A common working electrode in electroanalysis; its surface requires careful polishing before experiments [20]. |

| Microreactor System (Capillaries) | Provides a controlled, continuous-flow environment for chemical synthesis with efficient heat/mass transfer [1]. |

| Syringe Pumps | Enable precise and continuous dosage of starting materials in flow chemistry applications [1]. |

| Inline FT-IR Spectrometer | Allows for real-time reaction monitoring and immediate feedback for optimization algorithms [1]. |

Key Selection Guidelines

Choosing between Simplex and DOE depends on the project's goal:

- Use the Simplex Method when your goal is to quickly find the best operating conditions with minimal initial experiments, especially in dynamic or continuous processes where real-time adjustment is beneficial [1].

- Use Design of Experiments when your goal is to thoroughly understand the process, identify all critical factors and their interactions, and build a predictive model for future use [19].

For complex projects, a hybrid approach is often most effective: use an initial fractional factorial DOE to screen for significant factors, followed by a Simplex optimization to finely tune those factors toward the optimum [20].

In the field of process optimization, researchers and drug development professionals often face a critical methodological choice: using traditional Design of Experiments (DOE) approaches or employing Simplex-based algorithms. This guide provides an objective comparison of these methodologies, focusing on their application in navigating response surfaces to identify optimal process conditions.

Response Surface Methodology (RSM) is a collection of mathematical and statistical techniques that explores relationships between several explanatory variables and one or more response variables [15]. It employs sequential designed experiments to obtain an optimal response, typically using second-degree polynomial models to approximate these relationships [15]. In contrast, the Simplex method represents a directed approach that navigates the experimental space by moving along the edges of a geometric polytope, reflecting away from unfavorable regions [18] [8].

The core distinction lies in their fundamental approaches: RSM relies on statistical modeling of a predefined experimental space, while Simplex employs a sequential optimization algorithm that geometrically traverses the response surface. This comparison examines their relative performance through experimental data and case studies, particularly in bioprocessing applications.

Table 1: Fundamental Methodological Differences

| Characteristic | Design of Experiments (RSM) | Simplex Method |

|---|---|---|

| Approach | Statistical modeling of predefined space | Geometric traversal of response surface |

| Experimental Design | Pre-planned experiments (e.g., CCD, BBD) | Sequential experiments based on previous results |

| Model Dependency | Relies on polynomial models | Directly uses response values |

| Optimality Guarantees | Model-dependent | Converges to local optimum |

| Computational Overhead | Higher for complex models | Minimal between iterations |

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Response Surface Methodology Framework

RSM operates through a structured sequence of designed experiments. The typical workflow begins with factorial designs to identify significant variables, followed by more complex designs like Central Composite Design (CCD) or Box-Behnken Design (BBD) to estimate second-order polynomial models [21] [15].

CCD extends factorial designs by adding center points and axial (star) points, allowing estimation of both linear and quadratic effects [21]. The key components include:

- Factorial points: Represent all combinations of factor levels

- Center points: Repeated runs at the midpoint to estimate experimental error

- Axial points: Positioned along each factor axis at a distance α from the center to capture curvature

For a quadratic RSM model with dependent variable Y and independent variables Xᵢ and Xⱼ, the standard form is expressed as: Y = β₀ + ∑ᵢ βᵢ Xᵢ + ∑ᵢ ∑ⱼ βᵢⱼ Xᵢ Xⱼ + ε [21]

This model captures main effects (βᵢ), interaction effects (βᵢⱼ), and curvature in the response surface. The coefficients are typically estimated using regression analysis via least squares methods [21].

Simplex Method Framework

The Simplex algorithm operates by progressing step-by-step along the edges of the feasible region defined by constraints [18]. In its experimental implementation, known as the Grid Compatible Simplex Algorithm, the method navigates coarsely gridded data typical of early-stage bioprocess development [3].

The algorithm begins by assigning monotonically increasing integers to the levels of each factor and replacing missing data points with highly unfavorable surrogate points [3]. After defining an initial simplex, the method enters an iterative process where it:

- Suggests test conditions for evaluation

- Converts obtained responses into new test conditions

- Moves away from unfavorable regions toward promising experimental conditions

- Continues until identifying an optimum [3]

For constrained optimization problems in standard form: Minimize cᵀx subject to Ax ≤ b, x ≥ 0 the algorithm introduces slack variables to convert inequality constraints to equalities, then pivots between vertices of the feasible polytope by swapping dependent and independent variables [18].

Diagram 1: Simplex Algorithm Workflow (67 characters)

Comparative Performance Analysis

Case Study: Bioprocess Optimization

In a direct comparison for identifying bioprocess "sweet spots," a novel Hybrid Experimental Simplex Algorithm (HESA) was evaluated against conventional RSM approaches [8]. The study investigated the effect of pH and salt concentration on binding of green fluorescent protein, and examined the impact of salt concentration, pH, and initial feed concentration on binding capacities of a FAb′ [8].

Table 2: Performance Comparison in Bioprocess Optimization

| Metric | Simplex (HESA) | RSM Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Sweet Spot Definition | Better defined operating boundaries | Adequately defined regions |

| Experimental Cost | Comparable to DoE methods | Comparable to HESA |

| Information Return | Superior size, shape, location data | Standard process characterization |

| Implementation Complexity | Lower computational requirements | Higher modeling complexity |

| Boundary Identification | Excellent for operating envelopes | Requires additional validation |

HESA demonstrated particular advantages in delivering valuable information regarding the size, shape, and location of operating "sweet spots" that could be further investigated in follow-up studies [8]. Both methods returned equivalent experimental costs, establishing HESA as a viable alternative for scouting studies in bioprocess development [8].

Multi-Objective Optimization Performance

For problems involving multiple responses, a grid-compatible Simplex variant was extended to multi-objective optimization using the desirability approach [3]. Three high-throughput chromatography case studies were presented, each with three responses (yield, residual host cell DNA content, and host cell protein content) amalgamated through desirability functions [3].

The desirability approach scales multiple responses (yₖ) between 0 and 1 using functions that return individual desirabilities (dₖ). For responses to be maximized: dₖ = [(yₖ - Lₖ)/(Tₖ - Lₖ)]^wₖ for Lₖ ≤ yₖ ≤ Tₖ where Tₖ is the target value, Lₖ is the lower limit, and wₖ are weights determining the relative importance of reaching Tₖ [3]. The overall desirability D is calculated as the geometric mean of individual desirabilities.

In these challenging case studies with strong nonlinear effects, the Simplex approach avoided the deterministic specification of response weights by including them as inputs in the optimization problem [3]. This rendered the approach highly successful in delivering rapidly operating conditions that belonged to the Pareto set and offered superior and balanced performance across all outputs compared to alternatives [3].

Table 3: Multi-Objective Optimization Success Rates

| Optimization Method | Success Rate | Computational Time | Weight Specification | Pareto Optimality |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grid Simplex | High | Sub-minute | Flexible input | Guaranteed |

| DoE with Quartic Models | Low | Significant | Pre-specified | Not guaranteed |

| DoE with Desirability | Moderate | Moderate | Pre-specified | Achieved |

The Simplex method located optima efficiently, with performance relatively independent of starting conditions and requiring sub-minute computations despite its higher-order mathematical functionality compared to DoE techniques [3]. In contrast, despite adopting high-order quartic models, the DoE approach had low success in identifying optimal conditions [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 4: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Optimization Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function in Optimization Studies | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Osmotic Agents | Create concentration gradients for dehydration processes | Maltose, fructose, lactose, FOS in osmotic dehydration [22] |

| Chromatography Resins | Separation and purification of target molecules | Weak anion exchange and strong cation exchange resins [3] |

| Buffer Systems | Maintain precise pH control during experiments | Investigation of pH effects on protein binding [8] |

| Analytical Standards | Quantification of response variables | Host cell protein (HCP) and DNA content analysis [3] |

| Cell Culture Components | Source of biological material for optimization | E. coli homogenate and lysate for protein binding studies [8] |

Methodological Workflows for Experimental Implementation

Diagram 2: Optimization Methodology Selection (52 characters)

RSM Experimental Protocol

- Factor Identification: Clearly define factors that may influence the response, including process parameters and material properties [21]

- Factor Level Selection: Determine the range and levels for each factor to comprehensively understand the factor space [21]

- Experimental Design Selection: Choose appropriate design (CCD, BBD, or factorial) that optimally utilizes resources while providing robust information [21]

- Model Fitting: Use regression analysis to estimate coefficients for the quadratic model Y = β₀ + ∑βᵢXᵢ + ∑∑βᵢⱼXᵢXⱼ + ε [21]

- Model Validation: Employ ANOVA and residual analysis to validate model adequacy [22]

- Optimization: Utilize numerical techniques to identify optimal factor settings [21]

Simplex Experimental Protocol

- Search Space Preprocessing: Assign monotonically increasing integers to factor levels and replace missing data points with unfavorable surrogate values [3]

- Initial Simplex Definition: Select starting point or initial simplex based on preliminary knowledge or space-filling criteria [3]

- Vertex Evaluation: Evaluate experimental conditions defined by coordinates of simplex vertices in input space [3]

- Iterative Refinement: Suggest test conditions based on obtained responses, moving away from unfavorable regions [3]

- Optimality Checking: Monitor improvement in objective function until convergence criteria met [18]

- Validation: Confirm optimal conditions with additional experiments when necessary [8]

For researchers and drug development professionals, the choice between Simplex and RSM approaches depends heavily on specific project requirements. The Hybrid Experimental Simplex Algorithm (HESA) and grid-compatible variants demonstrate distinct advantages for early-stage scouting studies where process boundaries are poorly defined and rapid convergence is valuable [8] [3]. These methods excel in identifying operating "sweet spots" with comparable experimental costs to DoE methodologies while providing superior definition of operating boundaries [8].

RSM remains a powerful approach when comprehensive process characterization is required and when the experimental space is well-defined enough to support statistical modeling [21] [15]. The method provides detailed interaction effects and response surface visualizations that facilitate deep process understanding.

For drug development professionals facing increasing pressure to accelerate process development while maintaining robustness, the strategic integration of both methodologies may offer the optimal approach—using Simplex methods for initial scouting and boundary identification, followed by RSM for detailed characterization of promising regions.

In the pursuit of optimization and process understanding in scientific research and drug development, two distinct methodological philosophies have emerged: model-based approaches, primarily embodied by traditional Design of Experiments (DOE), and model-agnostic approaches, such as the Simplex method. The fundamental distinction lies in their reliance on prior knowledge and assumptions about the system under investigation. Model-based methods leverage statistical models and theoretical understanding to guide efficient experimentation, making them powerful when system behavior is reasonably well-understood [23]. In contrast, model-agnostic methods, including various Simplex techniques and space-filling designs, operate without presupposing a specific model structure, making them robust and effective for exploring complex or poorly understood systems where theoretical understanding is limited [23] [24].

This dichotomy represents a critical trade-off between efficiency and robustness. The choice between these philosophies is not merely technical but strategic, impacting resource allocation, experimental timelines, and the very nature of the knowledge gained. This guide provides an objective comparison of these approaches, supported by experimental data and contextualized for researchers and professionals in drug development and related scientific fields.

Philosophical Foundations and Methodological Principles

Model-Based Design of Experiments (DOE)

Model-based DOE represents the natural evolution of classical statistical designs, building upon theoretical understanding of system behavior to guide experimentation efficiently [23]. The core principle is the use of a predefined statistical model (e.g., a polynomial response surface) to plan experiments that optimally estimate the model's parameters. This approach embodies a deductive reasoning process, where prior knowledge is formally incorporated into the experimental design.

Key methodologies within this philosophy include:

- Response Surface Methodology (RSM): Includes designs like Central Composite Designs (CCD) and Box-Behnken Designs, which assume quadratic response surfaces and excel at estimating main effects, interactions, and quadratic effects [23].

- Factorial Designs: Used for screening studies to identify influential factors from a larger set of potential variables [25].

- Bayesian Optimization: Modern computational approaches that combine surrogate models, typically Gaussian Processes, with acquisition functions that mathematically balance exploration and exploitation [23].

The pharmaceutical industry has increasingly adopted model-based DOE to implement Quality by Design (QbD) principles, where product and process understanding is the key enabler of assuring final product quality [26]. In QbD, the mathematical relationships between Critical Process Parameters (CPPs) and Material Attributes (CMAs) with the Critical Quality Attributes (CQAs) define the design space [26].

Model-Agnostic Simplex Approaches

Model-agnostic methods offer robust alternatives that rely on geometric or logical principles rather than statistical assumptions [23]. These approaches embrace uncertainty and are particularly valuable when system behavior is poorly understood, highly complex, or expected to be non-linear [24]. They operate on an inductive reasoning principle, allowing patterns and relationships to emerge from the data itself.

Key methodologies in this category include:

- Simplex-Based Methods: The Basic Simplex Method uses geometric reflection operations to navigate the response surface, while the Modified Simplex Method incorporates expansion and contraction operations to adapt step sizes based on observed responses [23].

- Space-Filling Designs: Such as Latin Hypercube Sampling, and Maximin and Minimax designs, which focus on geometric spacing to provide efficient coverage of high-dimensional spaces without assuming a specific underlying model [23].

- Adaptive Approaches: These methods start with geometric principles but incorporate observed responses to adjust subsequent experimental locations, creating a bridge between purely model-agnostic and model-based approaches [23].

The model-agnostic philosophy is particularly effective when dealing with systems where underlying relationships are complex or unknown, as it avoids potential bias from incorrect model specification [23] [24].

Conceptual Workflow Comparison

The fundamental difference in how these approaches sequence knowledge-building and model-building can be visualized in their workflows:

Experimental Comparison and Performance Data

Quantitative Performance Metrics

Direct comparative studies in scientific literature reveal context-dependent performance characteristics for both approaches. The table below summarizes quantitative findings from various experimental optimization studies:

Table 1: Experimental Performance Comparison of DOE and Simplex Approaches

| Application Context | Model-Based DOE Performance | Model-Agnostic Simplex Performance | Key Findings | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fed-Batch Bioprocess Optimization (S. cerevisiae) | 30% increase in biomass concentration using model-assisted DOE | Not directly tested in study | mDoE approach significantly reduced required experiments; combined prior knowledge with statistical design | [27] |

| Water/Wastewater Treatment | RSM with CCD: R² = 0.9884 for modeling COD reduction | Limited reported data for simplex | DOE demonstrated high accuracy for modeling complex interactions in environmental systems | [25] |

| Formulation Development (Pharmaceutical) | Superior for establishing design space and meeting QTPP | Effective for complex rheological properties with unknown relationships | Choice depends on response complexity; hybrid approaches often beneficial | [24] [26] |

| General Process Optimization | Excellent efficiency with good theoretical understanding | Superior robustness with limited system knowledge | Simplex excels with complex responses; DOE better for additive responses | [23] [24] |

Case Study: Bioprocess Optimization with Model-Assisted DOE

A detailed case study optimizing a fed-batch process for Saccharomyces cerevisiae demonstrates the power of modern model-based approaches. Researchers implemented a model-assisted DOE (mDoE) approach that combined mathematical process modeling with statistical design principles [27].

Experimental Protocol:

- Objective Definition: Maximize biomass concentration in fed-batch cultivation

- Factor Selection: pH value, feeding rates of glucose (FGlc) and nitrogen source (FN)

- Model Development: Structured mathematical model based on prior knowledge and preliminary experiments

- Monte Carlo Simulation: Parameter probability functions derived from measurement errors

- DoE Design & Evaluation: Computational evaluation of experimental designs using desirability function

- Experimental Validation: Only highest-ranked experiments (2-4) were performed

Results: The mDoE approach achieved a 30% increase in biomass concentration compared to previous experiments while significantly reducing the number of required cultivations [27]. This demonstrates how incorporating mechanistic knowledge into statistical design can enhance efficiency.

Methodological Trade-offs in Practical Applications

Table 2: Methodological Characteristics and Trade-offs

| Characteristic | Model-Based DOE | Model-Agnostic Simplex |

|---|---|---|

| Prior Knowledge Requirement | High - depends on theoretical understanding | Low - operates with minimal assumptions |

| Experimental Efficiency | High - optimal information per experiment | Moderate - may require more experiments |

| Handling of Complex Nonlinearity | Limited by model specification | Excellent - adapts to emergent patterns |

| Resource Requirements | Lower when model is correct | Potentially higher for exploration |

| Risk of Model Misspecification | High - incorrect model leads to bias | Low - no presupposed model form |

| Interpretability of Results | High - clear parameter estimates | Moderate - geometric progression to optimum |

| Implementation Complexity | Higher initial setup | Simpler initial implementation |

Decision Framework for Method Selection

Contextual Selection Criteria

The choice between model-based and model-agnostic approaches should be guided by specific characteristics of the research problem and constraints. The following diagram illustrates key decision factors:

Practical Implementation Guidelines

When to Prefer Model-Based DOE

Model-based approaches are particularly advantageous when:

- Strong theoretical understanding of the system exists [23]

- Resource constraints limit the total number of experiments [23] [24]

- The primary objective is predictive modeling rather than exploration [24]

- Regulatory requirements demand formal design space definition (e.g., pharmaceutical QbD) [26]

- System behavior is expected to be moderately complex and well-captured by statistical models

As one expert notes, "Strong theoretical understanding suggests the use of model-based methods, while limited system knowledge points toward model-agnostic approaches" [23].

When to Prefer Model-Agnostic Simplex

Simplex and related model-agnostic methods excel in these scenarios:

- Limited prior knowledge about system behavior [23]

- Highly complex or non-linear responses are anticipated [24]

- The research objective is primarily exploratory [24]

- Unexpected interactions or behaviors are suspected

- Dealing with novel systems or formulations with unknown characteristics

One practitioner observes this dilemma: "Price might be a very easy response to model (additive contribution of factors), whereas for rheological properties you may encounter some strong non-linearities depending on the ratio of some raw materials in the formulation" [24].

Hybrid Approaches

Contemporary optimization methods increasingly blur traditional categorical boundaries [23]. Hybrid strategies include:

- Starting with space-filling designs for initial exploration, then transitioning to model-based optimization once patterns emerge

- Using model-based approaches to place points in edges/corners/vertices of the experimental space, and augmenting with space-filling points with the remaining budget [24]

- Batch Bayesian Optimization that combines adaptive learning of sequential methods with the efficiency of parallel execution [23]

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Reagents for Experimental Optimization

| Reagent/Material | Function in Optimization Studies | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Agrano strain) | Model organism for bioprocess optimization studies | Fed-batch process optimization [27] |

| Glucose and Nitrogen Sources (Yeast Extract, Soy Peptone) | Nutrient factors in fermentation media optimization | Bioprocess development [27] |

| Ethyl Acetoacetate (EAA) | Substrate for biocatalytic conversion studies | Whole-cell biocatalysis optimization [27] |

| Standard Chemical Reagents | Formulation components for mixture designs | Pharmaceutical formulation development [24] |

| Analytical Standards | Reference materials for response quantification | All application contexts |

Computational Tools and Software

Modern implementation of both philosophies relies on specialized software:

- Statistical Packages (JMP, R, Python/SciPy) for designing and analyzing both model-based and model-agnostic experiments [24]

- Model-Assisted DOE Toolboxes (MATLAB, R implementations) that combine mathematical modeling with experimental design [27]

- Custom Design Platforms for handling complex constraints and multiple factor types [24]

- Specialized Mixture Design Software for formulation optimization problems [23] [24]

The comparison between model-based DOE and model-agnostic Simplex approaches reveals a nuanced landscape where neither philosophy dominates universally. Each approach has distinct strengths that make it suitable for different research contexts within drug development and scientific optimization.

Model-based DOE provides structured efficiency when theoretical understanding exists, enabling rigorous design space definition and predictive modeling—attributes highly valued in regulated environments like pharmaceutical development [26]. Conversely, model-agnostic Simplex methods offer adaptive robustness when exploring novel systems with complex, poorly understood behaviors, preventing premature constraint by incorrect model assumptions [23] [24].

The future of experimental optimization lies in adaptive methodologies that can seamlessly transition between these philosophies based on accumulating knowledge [23]. As one expert predicts: "The future lies in methods that can seamlessly adapt between model-based and model-agnostic approaches while balancing sequential and parallel execution strategies based on practical constraints and accumulated knowledge" [23]. Furthermore, the integration of machine learning techniques with traditional experimental design promises more sophisticated surrogate models and improved handling of complex, constrained systems [23] [28].

For researchers and drug development professionals, the key insight is that methodological philosophy should follow research context—leveraging model-based efficiency when knowledge permits, while employing model-agnostic robustness when confronting the unknown. This pragmatic, context-aware approach to experimental optimization will ultimately accelerate scientific discovery and process development across diverse domains.

Practical Implementation: Applying DOE and Simplex in Drug Development

A Step-by-Step Guide to Executing a DOE Study

The Simplex-DOE Debate in Scientific Research

In the field of scientific research, particularly in drug development, efficiently identifying optimal process conditions is a fundamental challenge. Two methodological approaches offer different pathways: traditional Design of Experiments (DOE) and the Simplex method. DOE is a branch of applied statistics that deals with planning, conducting, analyzing, and interpreting controlled tests to evaluate the factors that control the value of a parameter or group of parameters [29]. It is a systematic, structured approach to experimentation. In contrast, the Hybrid Experimental Simplex Algorithm (HESA) is an iterative, sequential method that uses a decision rule to guide the experimenter toward a region of optimal performance, or a 'sweet spot' [8].

The core of the debate hinges on the trade-off between comprehensive understanding and experimental efficiency. Traditional DOE, especially full factorial designs, studies the response of every combination of factors and factor levels [29]. This provides a complete map of the experimental space, revealing complex interactions between factors. The Simplex method, however, is designed to locate a subset of experimental conditions necessary for the identification of an operating envelope more efficiently, often requiring fewer experimental runs to find a high-performing region [8]. This guide will provide a detailed, step-by-step framework for executing a DOE study, while objectively comparing its performance and outcomes with those achievable via the Simplex methodology.

Principles of Design of Experiments

Before detailing the steps, it is crucial to understand the core principles that underpin a robust DOE:

- Randomization: This refers to the random order in which the trials of an experiment are performed. A randomized sequence helps eliminate the effects of unknown or uncontrolled variables, thereby reducing bias [29].

- Replication: This is the repetition of a complete experimental treatment, including the setup. Replication allows the researcher to obtain an estimate of experimental error and gain a more reliable determination of the effect under investigation [29].

- Blocking: When randomizing a factor is impossible or too costly, blocking lets you restrict randomization by carrying out all trials with one setting of the factor and then all trials with the other setting. This is used to account for nuisance variables that are not of primary interest [29].

An iterative approach is often best. Rather than relying on a single, large experiment, it is more economical and logical to move through stages of experimentation, with each stage providing insight for the next [30].

A Step-by-Step Protocol for Executing a DOE

The following section outlines a generalized, five-step protocol for conducting a DOE. This framework integrates best practices from statistical and research methodology.

Step 1: Define Your Variables and Hypothesis

Objective: Formulate a clear, testable research question and identify all relevant variables.

- Action: Begin by listing your independent (input) and dependent (output) variables [31].

- Example: In a study on protein binding, the independent variables could be pH and Salt Concentration, while the dependent variable could be Binding Capacity [8].

- Action: Identify potential extraneous or confounding variables (e.g., temperature fluctuations, source material batch) and plan how to control them, either experimentally or statistically [31].

- Action: Write a specific, testable hypothesis.

Step 2: Design the Experimental Treatments

Objective: Create a design matrix that defines all the experimental conditions to be tested.

- Action: For each input factor, determine the extreme (but realistic) high and low levels you wish to investigate [29]. These are often coded as +1 and -1 for calculation purposes.

- Action: Select the type of experimental design. For an initial screening study, a full factorial design is common. This involves studying every combination of all factors and all levels [29]. The number of experimental runs can be calculated using the formula 2^n, where n is the number of factors. For a 2-factor experiment, this requires 4 runs [29].

The design matrix for a 2-factor, 2-level full factorial DOE is structured as follows:

Table 1: Design Matrix for a 2-Factor Full Factorial DOE

| Experiment # | Input A (pH) Level | Input B (Salt Concentration) Level |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | -1 | -1 |

| 2 | -1 | +1 |

| 3 | +1 | -1 |

| 4 | +1 | +1 |

Step 3: Assign Subjects and Run the Experiment

Objective: Execute the experiments as per the design matrix while minimizing bias.

- Action: Determine your sample size and how test subjects (e.g., cell culture plates, chemical samples) will be assigned to the treatment groups. Use randomization to assign subjects to groups at random to avoid systematic bias [31].