Single Emitter vs. Multi-Inlet Capillary: Maximizing Ion Transmission for Advanced Mass Spectrometry

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of ion transmission efficiency at the ESI-MS interface, comparing conventional single emitter/single inlet designs against advanced multi-inlet capillary and subambient pressure configurations.

Single Emitter vs. Multi-Inlet Capillary: Maximizing Ion Transmission for Advanced Mass Spectrometry

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of ion transmission efficiency at the ESI-MS interface, comparing conventional single emitter/single inlet designs against advanced multi-inlet capillary and subambient pressure configurations. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, we explore the fundamental principles governing ionization and transmission, detail methodologies for implementing enhanced interface designs, address key optimization challenges, and present validated performance comparisons. The scope covers practical strategies for significantly improving MS sensitivity, which is critical for applications ranging from proteomics to pharmaceutical analysis, ultimately enabling lower detection limits and more robust analytical data.

Ion Transmission Fundamentals: The Bottleneck in ESI-MS Sensitivity

Defining Ion Utilization Efficiency in ESI-MS Interfaces

In electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS), the ultimate sensitivity achievable is not solely determined by the mass analyzer's performance but is profoundly influenced by the efficiency of the processes that occur before ions even reach the high vacuum regions. The ion utilization efficiency of an ESI-MS interface serves as a critical performance metric, fundamentally defining the proportion of analyte molecules in solution that are successfully converted to gas-phase ions and transmitted through the interface to reach the mass spectrometer detector [1]. This parameter encapsulates two distinct but interconnected processes: the ionization efficiency in the ESI source itself, where analyte molecules in solution are converted to gas-phase ions, and the ion transmission efficiency through the ESI-MS interface, which governs how many of these generated ions successfully navigate the path into the mass spectrometer [2] [3].

The research community has increasingly recognized that dramatic sensitivity improvements in ESI-MS are more readily achievable through interface optimization rather than through incremental improvements in mass analyzer technology [1]. This understanding has driven systematic investigations into various interface configurations, particularly in the context of single emitter versus multi-inlet capillary designs, with the goal of quantifying and maximizing the overall ion utilization efficiency. The fundamental challenge in these evaluations has been correlating raw electrical current measurements with actual analyte ions that successfully reach the detector, leading to sophisticated methodologies that differentiate between transmitted gas-phase ions versus charged droplets and solvent clusters [1] [4].

Experimental Approaches for Quantifying Ion Utilization Efficiency

Core Measurement Methodology

Evaluating ion utilization efficiency requires carefully designed experiments that can distinguish between total electric current and meaningful analyte ion signal. The foundational approach involves measuring the total gas-phase ion current transmitted through the interface and correlating it with the observed ion abundance in the corresponding mass spectrum [1] [2]. This methodology typically employs a tandem ion funnel interface where the low-pressure ion funnel can function as a charge collector when connected to a picoammeter [1]. This arrangement allows researchers to differentiate between the total electric current (measured by the picoammeter) and the total ion current or extracted ion current for specific analytes (measured by the mass spectrometer) [1].

A key innovation in these measurements involves electrically isolating the front surface of the ESI interface from the inner wall of the heated inlet capillary, enabling distinction between current losses on these different surfaces [4]. Additionally, spatial profiling of the ES current lost to the front surface has been achieved using linear arrays of miniature electrodes positioned adjacent to the inlet capillary entrance [4]. These technical refinements have provided unprecedented insight into where and how ions are lost during the transmission process.

Interface Configurations for Comparative Studies

Researchers have systematically compared several interface configurations to quantify their relative ion utilization efficiencies:

- Single Emitter/Single Inlet Capillary: This conventional configuration positions a single electrospray emitter approximately 2-3 mm from a single heated inlet capillary [1] [5].

- Single Emitter/Multi-Inlet Capillary: This design utilizes a single emitter but employs multiple inlet capillaries (typically seven arranged in a hexagonal pattern) to increase sampling capacity [1].

- SPIN-MS Interface: The subambient pressure ionization with nanoelectrospray (SPIN) interface removes the conventional sampling inlet capillary entirely by placing the ESI emitter inside the first vacuum chamber of the mass spectrometer (at approximately 19-22 Torr) adjacent to the entrance of an electrodynamic ion funnel [1].

- Emitter Arrays: Multi-emitter configurations (typically 19 emitters) coupled with specialized multi-capillary inlets designed to handle the increased ion production [5].

Standardized Experimental Conditions

To ensure meaningful comparisons across different interface configurations, researchers typically maintain standardized conditions:

- Instrumentation: Experiments often utilize orthogonal time-of-flight (TOF) mass spectrometers with standard interfaces replaced by tandem ion funnel configurations [1] [5].

- Ion Funnel Parameters: The high-pressure ion funnel typically operates with RF peak-to-peak voltages of 300 V at 2.55 MHz with a DC gradient of 19 V/cm, while the low-pressure funnel operates at 100 Vp-p at 730 kHz with a similar DC gradient [1].

- Sample Systems: Studies frequently employ standardized peptide mixtures (angiotensin I, neurotensin, bradykinin, etc.) at concentrations ranging from 100 nM to 1 μM in solvent systems comprising 0.1% formic acid in 10% acetonitrile/water [1] [5].

- Emitter Specifications: NanoESI emitters are typically prepared by chemically etching fused silica capillaries (150 μm O.D., 10 μm I.D.) to create stable ion sources without internal tapering that could lead to clogging [1] [5].

Comparative Analysis of ESI-MS Interface Technologies

Performance Metrics Across Interface Configurations

The systematic evaluation of different ESI-MS interface configurations has revealed significant differences in their ion utilization efficiencies. The table below summarizes key performance characteristics:

Table 1: Comparative Performance of ESI-MS Interface Configurations

| Interface Configuration | Ion Utilization Efficiency | Key Advantages | Limitations/Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single Emitter/Single Inlet Capillary | Baseline for comparison | Simple design, robust operation | Significant ion losses (>80%) from incomplete desolvation and transmission [4] |

| Single Emitter/Multi-Inlet Capillary | Moderate improvement over single inlet | Increased sampling capacity | Limited by global gas dynamic effects of capillary conductance [4] |

| SPIN-MS Interface | Highest reported efficiency | Eliminates inlet capillary constraint; achieves ~50% ionization efficiency [3] | Requires vacuum interlock; more complex implementation [1] |

| Emitter Array with Multi-Capillary Inlet | 9-11 fold sensitivity enhancement [5] | Enables nanoESI benefits at higher LC flow rates; improved S/N ratio | Fabrication complexity; requires specialized ion optics [5] |

Quantitative Transmission and Sensitivity Data

Controlled experiments provide quantitative comparisons of transmission efficiency and sensitivity gains:

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Metrics from Experimental Studies

| Measurement Parameter | Single Emitter/ Single Inlet | Single Emitter/ Multi-Inlet | SPIN Interface | Emitter Array/ Multi-Capillary |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transmitted Ion Current | Baseline | 1.5-2x increase [1] | Significantly higher than capillary inlets [1] | Highest measured current [1] |

| Observed MS Signal Intensity | Baseline | Moderate improvement | Substantial improvement [1] | 9-11 fold increase for peptides [5] |

| LC Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio | Baseline | Not reported | Not reported | ~7-fold improvement [5] |

| Ion Loss Mechanisms | Primarily incomplete desolvation and surface collisions [4] | Similar to single inlet but distributed | Reduced desolvation requirements | Minimized through optimized gas dynamics |

Fundamental Trade-offs in Interface Design

The comparison between single emitter and multi-inlet approaches reveals several fundamental trade-offs:

- Flow Rate Considerations: Single emitter nanoESI operates optimally at very low flow rates (20-100 nL/min) where ionization efficiency is highest, but this conflicts with conventional LC flow rates [5]. Multi-emitter arrays effectively overcome this limitation by distributing higher LC flow rates (e.g., 2 μL/min) across multiple emitters, with each emitter operating in the optimal nanoESI regime [5].

- Gas Dynamic Limitations: Both single and multi-inlet capillaries face inherent gas dynamic constraints related to the conductance limit of the inlet capillaries, which creates a global effect on the shape of the electrospray plume rather than just local sampling effects [4].

- Desolvation Requirements: A critical finding across studies is that significant ion losses (exceeding 80%) can occur after transmission through the inlet due to incomplete desolvation, particularly at higher flow rates (1.0 μL/min) [4]. This highlights that simply transmitting more current does not guarantee improved analyte signal if the transmitted species are not fully desolved ions.

- Positioning Tolerance: SPIN interfaces demonstrate reduced sensitivity to precise emitter positioning compared to atmospheric pressure interfaces, as the vacuum environment minimizes droplet expansion and dispersion [1].

Technical Workflow for Efficiency Evaluation

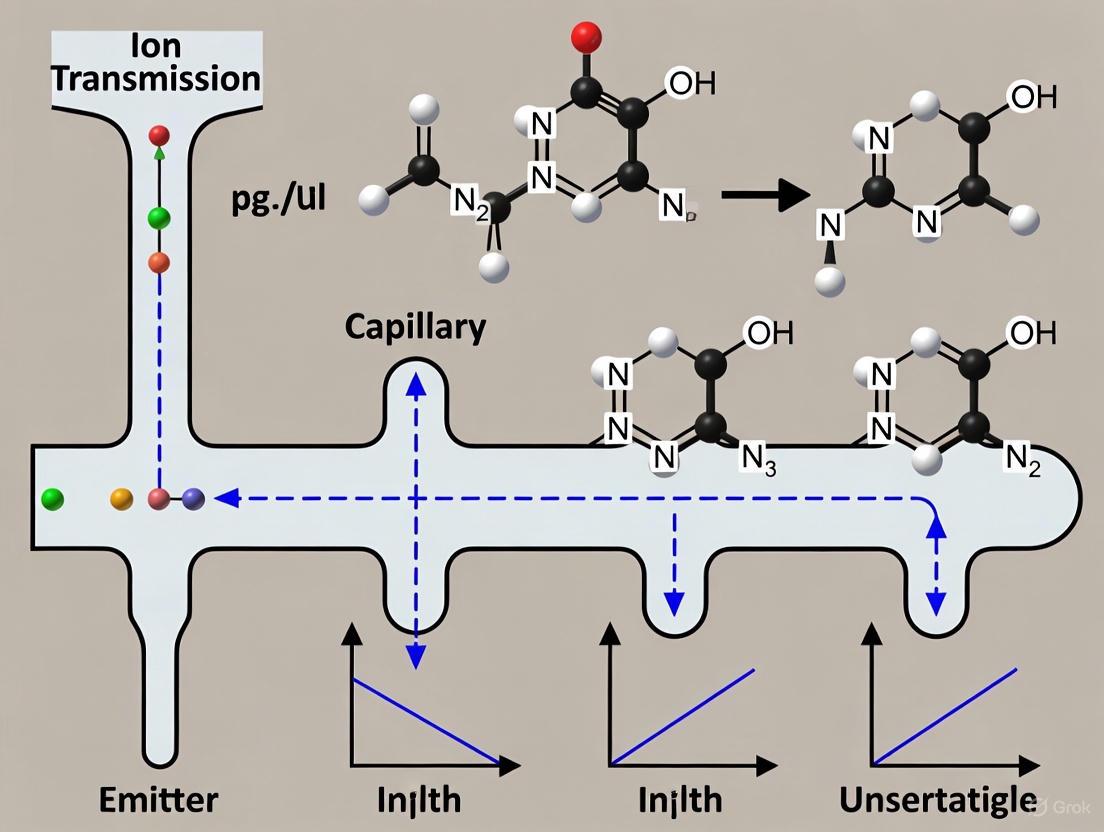

The experimental process for evaluating ion utilization efficiency follows a systematic workflow that can be visualized as follows:

Diagram 1: Workflow for ESI-MS interface efficiency evaluation. This systematic approach enables quantitative comparison of different interface configurations through correlation of electrical current measurements with mass spectral ion abundance.

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful experimentation in ESI-MS interface development requires specific research reagents and specialized materials. The following table details key components used in the cited studies:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for ESI-MS Interface Studies

| Category | Specific Items | Function/Purpose | Experimental Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard Analytic Samples | Angiotensin I, Neurotensin, Bradykinin, Fibrinopeptide A, Substance P [1] [5] | Performance benchmarking; standardized comparison | Typically used at 100 nM - 1 μM concentrations in 0.1% formic acid/10% acetonitrile |

| ESI Emitters | Chemically etched fused silica capillaries (20 μm I.D. × 150 μm O.D.) [5] | Nanoelectrospray ion generation | Etching creates stable emitters without internal tapering to prevent clogging |

| Emitter Arrays | 19-capillary arrays with epoxy sealing [5] | High ion current generation; flow rate distribution | Enables nanoESI benefits at higher LC flow rates (2 μL/min) |

| Mobile Phase Components | Formic acid, Trifluoroacetic acid (TFA), Acetonitrile (ACN) [1] [5] | LC separation; ionization enhancement | 0.1-0.2% acid concentration typical for peptide analysis |

| MS Interface Components | Heated inlet capillaries (430-490 μm I.D.), Tandem ion funnels [1] [5] | Ion transmission and focusing | Multi-capillary inlets designed to match emitter arrays |

| Specialized Gases | Heated CO₂ desolvation gas (~160°C) [1] | Droplet desolvation in SPIN interface | Critical for complete desolvation in subambient pressure environment |

The comprehensive comparison of ESI-MS interface technologies demonstrates that the conventional single emitter/single inlet capillary configuration, while robust and widely implemented, presents significant limitations in ion utilization efficiency due to extensive losses during transmission and desolvation. The emergence of multi-inlet approaches and particularly the SPIN-MS interface represents substantial advancements in maximizing the proportion of analyte ions that successfully reach the mass analyzer.

For researchers and drug development professionals, these findings have practical implications for method development. The SPIN interface configuration demonstrates superior ion utilization efficiency, making it particularly valuable for samples where sensitivity is limiting, such as in trace biomarker detection or pharmaceutical impurity profiling [1] [3]. Conversely, multi-emitter arrays with specialized multi-capillary inlets offer an excellent compromise for high-throughput LC-ESI-MS applications, enabling the sensitivity benefits of nanoESI while maintaining practical flow rates compatible with conventional separation systems [5].

The definitive experimental evidence shows that interface optimization represents one of the most productive avenues for sensitivity enhancement in ESI-MS applications. The systematic methodology for evaluating ion utilization efficiency—correlating transmitted ion current with observed mass spectral abundance—provides a robust framework for future interface innovations and objective performance comparisons across platforms. As ESI-MS continues to evolve toward increasingly demanding applications, these fundamental studies of ionization and transmission efficiency will remain essential for guiding technology development and method optimization in both academic and industrial settings.

In electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS), the interface between the atmospheric pressure ion source and the high-vacuum mass analyzer represents the most critical determinant of overall sensitivity. It is at this junction that the majority of analyte ions are lost before ever reaching the detector [1]. The achievable sensitivity of ESI-MS is largely governed by two fundamental efficiencies: the ionization efficiency in the ESI source itself, and the ion transmission efficiency through the ESI-MS interface [1] [3]. Despite decades of optimization, conventional ESI interfaces typically exhibit significant inefficiencies, with only a small fraction of generated analyte ions successfully traversing the pathway to detection [5].

This guide objectively compares the ion transmission performance of conventional single-emitter ESI sources against emerging multi-emitter and alternative interface technologies. Within the broader context of single emitter versus multi-inlet capillary ion transmission research, we examine quantitative experimental data that reveals substantial differences in ion utilization efficiency across interface configurations. By providing detailed methodologies and comparative performance metrics, this analysis aims to equip researchers with the evidence needed to select optimal ESI interface configurations for specific analytical challenges.

Understanding Ion Loss Mechanisms in ESI-MS Interfaces

The journey of an ion from solution to detector is fraught with potential loss mechanisms. In a conventional nanoESI source, the emitter is typically positioned 1-3 mm from the MS sampling inlet, which is often a flow-restricting heated capillary [1]. Analyte ions generated from charged droplets may be lost due to limited flow capacity through the inlet, incomplete droplet desolvation, or collisions with surfaces during transit through the interface capillary and subsequent apertures [1] [4].

A significant breakthrough in understanding these losses came from studies that quantitatively measured current loss throughout the ESI interface by electrically isolating the front surface of the interface from the inner wall of the heated inlet capillary [4]. This approach enabled researchers to distinguish losses on these two surfaces and revealed that while sampling efficiency into the inlet capillary could exceed 90% at optimal emitter distances (approximately 1 mm), substantial losses (exceeding 80%) occurred after transmission through the inlet due to incomplete desolvation at typical solution flow rates [4].

The phenomenon of ion suppression represents another major source of signal reduction occurring specifically at the ionization stage [6]. This occurs when co-eluting compounds, either from the sample matrix or exogenous sources, interfere with the ionization of target analytes. In ESI, suppression mechanisms include competition for limited charge available on ESI droplets, increased droplet viscosity/surface tension, and the presence of nonvolatile materials that prevent droplets from reaching the critical radius required for gas-phase ion emission [6].

Experimental Approaches for Quantifying Interface Efficiency

Methodologies for Assessing Ion Transmission

Evaluating the performance of ESI-MS interfaces requires specialized methodologies that can differentiate between various loss mechanisms. One effective approach involves measuring the total gas-phase ion current transmitted through the interface and correlating it with the observed ion abundance in the corresponding mass spectrum [1] [3]. In practice, this is accomplished by using a tandem ion funnel interface where the low-pressure ion funnel functions as a charge collector when connected to a picoammeter [1].

The ion utilization efficiency is generally defined as the proportion of analyte molecules in solution that are successfully converted to gas-phase ions and transmitted through the interface to reach the detector [1]. This metric provides a comprehensive assessment of overall interface performance, encompassing both ionization and transmission components. To characterize the nature of the ion cloud, researchers systematically measure both the total transmitted electric current through the high-pressure ion funnel and the total ion current measured at the MS detector across different interface configurations [1].

Key Experimental Parameters

Controlled studies of ESI interface efficiency typically investigate several critical parameters:

- Emitter distance to inlet: Optimal positioning is typically 1-2 mm [4] [5]

- Solution flow rate: NanoESI regimes (nL/min) significantly improve ionization efficiency [1]

- Inlet temperature: Affects desolvation efficiency and subsequent ion transmission [4]

- Ion funnel RF parameters: Voltage and frequency significantly impact transmission [7]

These parameters are systematically varied while measuring transmitted ion currents and spectral intensities to build a comprehensive picture of interface performance under different operational conditions.

Comparative Analysis of ESI-MS Interface Technologies

Interface Configurations and Performance Metrics

Experimental comparisons of ESI-MS interface technologies have revealed substantial differences in ion utilization efficiency. The most studied configurations include conventional single emitter/single inlet designs, multi-inlet approaches, and the subambient pressure ionization with nanoelectrospray (SPIN) interface [1] [3].

The table below summarizes the key performance characteristics of these interface configurations based on experimental data:

Table 1: Comparison of ESI-MS Interface Configurations and Performance Characteristics

| Interface Configuration | Ion Utilization Efficiency | Key Advantages | Limitations | Reported Sensitivity Enhancement |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single Emitter/Single Inlet Capillary | Baseline | Established technology, simple implementation | Significant ion losses, limited desolvation | Reference [1] |

| Single Emitter/Multi-Inlet Capillary | Moderate improvement | Increased sampling capacity | Complex alignment, limited emitter compatibility | Not quantified in available studies [1] |

| SPIN-MS with Single Emitter | High | Reduced losses, placement in first vacuum chamber | Requires vacuum interlock, specialized equipment | Significantly exceeds capillary-based interfaces [1] |

| SPIN-MS with Emitter Array | Highest | Combined benefits of array and SPIN technologies | Maximum complexity, custom fabrication | Greatest overall enhancement [1] |

| Multi-Emitter/Multi-Capillary Inlet | High | Enables nanoESI benefits at higher LC flow rates | Fabrication complexity, precise alignment required | 9-11 fold for peptides vs. single emitter [5] |

Quantitative Performance Data

Controlled experiments provide direct quantitative comparisons between interface technologies. The following table summarizes specific performance metrics reported across multiple studies:

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Metrics for ESI-MS Interface Technologies

| Interface Configuration | Flow Rate (per emitter) | Transmitted Ion Current | Signal Enhancement | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional NanoESI (Reference) | 20 nL/min | Baseline | 1x (reference) | Standard protein analysis [5] |

| 19-Emitter Array with Multi-Capillary Inlet | ~100 nL/min (total 2 μL/min) | Significantly increased | 9-11 fold for peptides from spiked proteins in human plasma digest [5] | High-flow LC-MS with nanoESI-like sensitivity [5] |

| 19-Emitter Array with Redesigned Multi-Capillary Inlet | ~100 nL/min (total 2 μL/min) | Further 60% improvement vs. previous multi-inlet | ~7-fold increase in LC peak signal-to-noise ratio [5] | Capillary LC separations at 2 μL/min [5] |

| SPIN-MS Interface | NanoESI flow rates | Highest measured | Overall ion utilization efficiency exceeds capillary-based interfaces [1] [3] | Ultrasensitive analyses where maximum sensitivity is required [1] |

The Multi-Emitter/Multi-Inlet Approach: Experimental Evidence

The multi-emitter/multi-inlet capillary approach represents a promising strategy for extending the sensitivity benefits of nanoelectrospray to higher flow rate separations. This technology typically involves arrays of chemically etched fused silica emitters (e.g., 19-emitter configurations) coupled with custom-designed multi-capillary inlets arranged in matching patterns [5]. The fundamental principle involves dividing the total LC flow among multiple emitters, thereby reducing the flow rate per emitter to the nanoESI regime (typically 20-100 nL/min per emitter) while maintaining the higher total flow rates required for analytical-scale separations [5].

This approach addresses a fundamental compromise in conventional LC-ESI-MS, where the flow rate is typically optimized for chromatographic performance rather than ionization efficiency. By decoupling these parameters, multi-emitter systems enable operation in the nanoESI regime even at total flow rates of 2 μL/min or higher [5]. The low dead volume of properly constructed emitter arrays preserves chromatographic peak shape and resolution, maintaining separation quality while significantly enhancing sensitivity [5].

Experimental Workflow and Configuration

The experimental implementation of multi-emitter/multi-inlet systems follows a specific workflow:

Diagram 1: Multi-Emitter LC-MS Experimental Workflow

Key components of this system include:

- Chemically etched emitters: Prepared from fused silica capillaries (20 μm i.d. × 150 μm o.d.) using hydrofluoric acid etching, producing emitters without internal tapering that are less prone to clogging [5]

- Emitter arrays: 19-capillary configurations assembled with epoxy sealing in precisely patterned arrays [5]

- Multi-capillary inlets: 19-capillary inlets with 400 μm i.d./500 μm o.d. capillaries with 500 μm center-to-center spacing, heated to 125°C [5]

- Tandem ion funnel interface: Specifically designed to accommodate increased gas load from multiple inlets, with high-pressure funnel (18 Torr) and conventional funnel (1.3 Torr) [5]

Performance Results and Applications

Experimental results demonstrate substantial benefits for the multi-emitter/multi-inlet approach. In analyses of tryptic digests from proteins spiked into human plasma, the 19-emitter array configuration produced an average 11-fold signal increase for peptides compared to a single emitter interface [5]. Perhaps equally importantly, the LC peak signal-to-noise ratio increased approximately 7-fold, significantly enhancing detection capability for low-abundance species in complex matrices [5].

The technique has proven particularly valuable for capillary LC separations operating at flow rates of approximately 2 μL/min, where it maintains the loading capacity and tolerance for dead volume that can be problematic in true nanoLC systems while providing nanoESI-level sensitivity [5]. The preservation of chromatographic performance combined with substantial sensitivity enhancements makes this approach particularly suited for proteomic analyses of complex samples where comprehensive detection is critical.

Alternative Interface Technologies: SPIN-MS and Vacuum Ionization

Subambient Pressure Ionization with Nanoelectrospray (SPIN)

The SPIN-MS interface represents a more fundamental reimagining of the ESI-MS interface by removing the constraint of a sampling inlet capillary entirely. Instead, the ESI emitter is placed directly inside the first vacuum chamber of the mass spectrometer, adjacent to the entrance of an electrodynamic ion funnel [1] [3]. This configuration operates at pressures of 19-22 Torr and positions the emitter approximately 1 mm from the first electrode of the high-pressure ion funnel [1].

In this configuration, the cylindrical outlet surrounding the emitter functions as the electrospray counter electrode, biased 50 V higher than the front plate of the high-pressure ion funnel [1]. Efficient droplet desolvation is accomplished using heated CO₂ gas (~160°C), with an additional CO₂ sheath gas provided around the ESI emitter to ensure electrospray stability and prevent electrical breakdown [1]. This arrangement achieves unprecedented ionization efficiencies, with reports of up to 50% ion utilization efficiency in subambient pressure ionization with nanoelectrospray [3].

Vacuum and Inlet Ionization Methods

Recent innovations have challenged conventional ESI paradigms through techniques collectively known as inlet and vacuum ionization. These methods include matrix-assisted ionization inlet (MAII), solvent-assisted ionization inlet (SAII), and related approaches that utilize the vacuum inherent in mass spectrometers and appropriate matrices to produce gas-phase ions without applied voltage or laser ablation [8].

In MAII, the analyte incorporated in a small molecule matrix is introduced into a heated inlet tube linking atmospheric pressure and the vacuum of the mass spectrometer, producing ESI-like charge states directly from solid-phase samples [8]. Similarly, SAII operates without a solid matrix, instead using solvents to produce abundant ions with charge states nearly identical to ESI [8]. These techniques demonstrate sensitivity comparable to or better than ESI at similar flow rates while offering simplified operation and reduced infrastructure requirements [8].

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Components for ESI Interface Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for ESI Interface Studies

| Component Category | Specific Examples | Function/Purpose | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Emitters | Chemically etched fused silica capillaries (20 μm i.d. × 150 μm o.d.) [5] | Nanoelectrospray generation without internal tapering | Reduced clogging, stable cone-jet mode at 20 nL/min [5] |

| Emitter Arrays | 19-emitter arrays from etched fused silica [5] | Divide total flow to maintain nanoESI regime per emitter | Enables higher total flow rates while preserving nanoESI benefits [5] |

| Ion Funnels | Tandem ion funnel interface [7] [5] | Efficient ion transmission through pressure gradients | Accommodates increased gas load from multi-capillary inlets [7] |

| Multi-Capillary Inlets | 19-capillary inlets (400 μm i.d., 500 μm spacing) [5] | Increased sampling capacity for emitter arrays | Heated to 125°C, matched to emitter array pattern [5] |

| Current Measurement | Picoammeter with ion funnel as charge collector [1] | Quantify transmitted ion current through interface | Enables calculation of ion utilization efficiency [1] |

| Desolvation Systems | Heated CO₂ sheath gas (~160°C) [1] | Enhanced droplet desolvation in SPIN interface | Prevents electrical breakdown, improves ion yield [1] |

The systematic comparison of ESI-MS interface technologies reveals a clear evolution from conventional single-emitter designs toward more sophisticated multi-emitter and alternative pressure configurations. Experimental evidence demonstrates that the multi-emitter/multi-inlet approach provides substantial sensitivity enhancements (7-11 fold for peptides in complex matrices) while maintaining compatibility with analytical-scale LC flow rates [5]. For applications demanding maximum sensitivity, the SPIN-MS interface achieves superior ion utilization efficiency by fundamentally reengineering the pressure environment and ion transmission pathway [1] [3].

These advancements carry significant implications for researchers designing mass spectrometry experiments. The choice of ESI interface configuration should be guided by specific analytical requirements, including necessary flow rates, sample complexity, and detection sensitivity needs. For high-flow LC-MS applications where sensitivity is paramount, multi-emitter arrays with matched multi-capillary inlets offer a compelling balance of performance and practicality. For the most challenging analyses where ultimate sensitivity is required, SPIN and vacuum ionization technologies provide cutting-edge performance, albeit with greater implementation complexity.

As ESI-MS continues to evolve, further innovations in interface design will likely focus on increasing robustness and accessibility of these enhanced ionization and transmission technologies, ultimately expanding the analytical capabilities available to researchers across chemical and biological disciplines.

Core Principles of Electrospray Ionization and Plume Formation

Electrospray Ionization (ESI) is a soft ionization technique that has profoundly transformed mass spectrometry, enabling the analysis of large, noncovalent biological macromolecules directly from liquid samples. The achievable sensitivity in ESI-mass spectrometry (ESI-MS) is not merely a function of the mass analyzer but is largely determined by the efficiency of two critical processes: the initial ionization of molecules into the gas phase at the emitter and the subsequent transmission of these ions through the atmospheric pressure interface into the high vacuum of the mass spectrometer [1]. This guide objectively compares the performance of conventional single emitter/single inlet interfaces against advanced multi-emitter/multi-inlet configurations, framing the discussion within broader research on optimizing ion transmission.

Fundamental Mechanisms of Electrospray Ionization

The electrospray process begins when a high voltage is applied to a liquid exiting a capillary nozzle, dispersing the sample into a fine aerosol of charged droplets [9] [10].

Plume Formation and Ion Generation Mechanisms

The formation of a stable electrospray plume is governed by a balance between electrostatic forces and surface tension. When a critical voltage—the Taylor Cone voltage—is applied, the liquid surface forms a cone with a specific 49.3° angle, from the tip of which a spray of charged droplets is emitted [9]. These primary droplets undergo solvent evaporation and Coulomb fissions, repeatedly splitting into smaller progeny droplets.

The final production of gas-phase ions is explained by two primary models:

Charge Residue Model (CRM): This model proposes that solvent evaporation from charged droplets continues until only a single analyte ion remains, carrying the residual charge of the final droplet [9]. The CRM is considered dominant for large molecules like folded proteins [10].

Ion Evaporation Model (IEM): This mechanism suggests that when droplets reach a sufficiently small size (approximately 20 nm in diameter), the electric field at their surface becomes strong enough to directly desorb solvated ions into the gas phase [9]. The IEM is thought to be more relevant for smaller ions [10].

The following diagram illustrates the complete electrospray ionization process from the Taylor cone formation to the generation of gas-phase ions via these two mechanisms:

Comparative Analysis: Single vs. Multi-Emitter/Multi-Inlet Systems

Ion transmission losses predominantly occur during the transfer from atmospheric pressure to the mass spectrometer's high vacuum region. Different interface designs aim to mitigate these losses.

Experimental Configurations and Methodologies

To objectively compare performance, researchers have systematically evaluated different ESI-MS interface configurations using standardized experimental protocols [1] [5].

Sample Preparation: A standard peptide mixture containing angiotensin I, neurotensin, bradykinin, and kemptide (500 nM each in 2:1 mobile phase A:B) is typically used for direct infusion experiments [5]. For LC-MS analyses, tryptic digests of proteins spiked into human plasma are employed to assess real-world performance [5].

ESI Emitters: Individual and multi-emitters are fabricated from fused silica capillaries (20 μm i.d. × 150 μm o.d.) via chemical etching, which creates emitters without an internal taper to resist clogging [5]. Multi-emitter arrays consist of 19 such capillaries assembled in a hexagonal pattern [5].

Interface Configurations:

- Single Emitter/Single Inlet: A conventional setup with one etched emitter positioned 1-2 mm from a single heated inlet capillary (430-490 μm i.d.) [1] [5].

- Multi-Emitter/Multi-Inlet: Arrays of 7 or 19 emitters coupled with corresponding multi-capillary inlets (400-490 μm i.d. each) with center-to-center spacing of 500 μm to 1.0 mm [1] [5].

- SPIN (Subambient Pressure Ionization with Nanoelectrospray) Interface: The emitter is placed inside the first vacuum chamber (19-22 Torr) adjacent to an electrodynamic ion funnel, eliminating the atmospheric pressure interface bottleneck [1].

Mass Spectrometry Analysis: Experiments are typically conducted using time-of-flight (TOF) mass spectrometers equipped with tandem ion funnel interfaces. The high-pressure ion funnel (operated at 18 Torr) uses RF voltages (170 Vp-p at 1.7 MHz) and DC gradients (17.0 V/cm) to focus ions, while the low-pressure funnel (1.3 Torr) uses lower RF voltages (100 Vp-p at 730 kHz) for further transmission [5].

Efficiency Measurements: The total transmitted gas-phase ion current is measured using the low-pressure ion funnel as a charge collector connected to a picoammeter. This electric current is correlated with the total ion current (TIC) and extracted ion currents (EIC) for specific analytes measured by the mass spectrometer to determine ion utilization efficiency [1].

Quantitative Performance Comparison

The following tables summarize key experimental findings comparing different ESI interface configurations:

Table 1: Ion Transmission Efficiency Across Different Interface Designs

| Interface Configuration | Relative Transmission Efficiency | Overall Ion Utilization Efficiency | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single Emitter/Single Inlet | 1x (baseline) | <5% | Standard configuration, simple operation |

| Multi-Emitter/Multi-Inlet | 7x higher than single inlet [11] | Not reported | Increased ion sampling from larger plume area |

| SPIN Interface | >7x higher than single inlet [1] | >50% [10] | Eliminates inlet capillary losses, enhanced desolvation |

Table 2: Analytical Sensitivity Enhancements in LC-MS Applications

| Performance Metric | Single Emitter | Multi-Emitter Array | Enhancement Factor |

|---|---|---|---|

| Average Peptide Signal Intensity | Baseline | 11-fold increase [5] | 11x |

| LC Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio | Baseline | ~7-fold increase [5] | 7x |

| Operational Flow Rate for LC | Compromised sensitivity at higher flows | Optimal sensitivity at 2 μL/min total flow [5] | Enables high-flow nanoESI benefits |

Technological Mechanisms and Workflow

The superior performance of multi-inlet systems stems from fundamental improvements in ion capture and transmission dynamics, as visualized in the following experimental workflow and ion transmission diagram:

The multi-capillary inlet improves transmission by expanding the effective sampling area, capturing more of the electrospray plume that would otherwise be lost to the surrounding surfaces. When coupled with electrodynamic ion funnels, which use RF fields and DC gradients to efficiently focus and transmit ions through pressure differentials, these systems achieve significantly higher ion utilization [11].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for ESI-MS Interface Studies

| Item | Specification | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Fused Silica Capillaries | 20 μm i.d. × 150 μm o.d. (Polymicro Technologies) | Fabrication of nanoESI emitters for single and multi-emitter arrays [5] |

| Standard Peptide Mixture | Angiotensin I, Neurotensin, Bradykinin, Kemptide (Sigma-Aldrich) | System performance evaluation and calibration [1] [5] |

| Mobile Phase Components | 0.1% Formic Acid, LC-MS Grade Acetonitrile, Purified Water | ESI solvent preparation to enhance conductivity and ionization efficiency [5] |

| Chemical Etching Solution | 49% Hydrofluoric Acid (Fisher Scientific) | Emitter fabrication without internal tapering to prevent clogging [5] |

| Epoxy Resin | Devcon HP250 (Danvers, MA) | Assembly and sealing of multi-emitter arrays [5] |

| Stainless Steel Inlet Capillaries | 400-490 μm i.d., 7.6 cm length | Construction of single and multi-capillary inlets for interface comparisons [1] |

The evolution from single to multi-emitter/multi-inlet ESI interfaces represents a significant advancement in mass spectrometry sensitivity. Quantitative experimental data demonstrates that multi-capillary inlet systems can provide approximately 7-fold higher ion transmission compared to conventional single inlet designs, while multi-emitter arrays coupled with these interfaces enable 11-fold signal enhancements for peptide analyses. The SPIN interface, which moves the ionization process into the first vacuum stage, achieves remarkable ion utilization efficiencies exceeding 50%. These technological improvements directly address the fundamental challenge in ESI-MS: the inefficient transfer of ions from atmospheric pressure to the high vacuum mass analyzer. For researchers and drug development professionals, selecting appropriate interface technology based on specific application requirements—whether conventional single inlets for routine analyses or advanced multi-inlet/SPIN configurations for maximum sensitivity with limited samples—is crucial for optimizing analytical outcomes.

In electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS), the journey from a charged droplet in the liquid phase to a desolvated ion in the gas phase represents the most critical transformation determining the sensitivity and quality of analysis. This process, known as desolvation, presents a formidable challenge: efficiently stripping solvent molecules from analyte ions without causing fragmentation or adduct formation. The efficiency of this process is not merely a function of the ionization source itself, but is profoundly affected by the design of the ESI-MS interface, which governs ion transmission into the mass spectrometer. Within this domain, a key research focus has emerged comparing the performance of single emitter/single inlet capillary designs against multi-inlet capillary and subambient pressure ionization with nanoelectrospray (SPIN) interfaces. The desolvation challenge sits at the intersection of fluid dynamics, electrochemistry, and instrument design, where incremental improvements can translate to significant gains in detection sensitivity for applications ranging from proteomics to drug development.

Ionization Mechanisms and Desolvation Pathways

The transformation of analytes from solvated species in charged droplets to gas-phase ions is described by two predominant, and sometimes competing, theoretical models. Understanding these mechanisms is essential for evaluating how different interface designs address the desolvation challenge.

- The Charged Residue Model (CRM): Originally proposed by Dole et al., this model suggests that a series of solvent evaporation and droplet fission events eventually produces "ultimate droplets" containing a single analyte molecule. The complete evaporation of solvent from this final droplet leaves the analyte holding the residual charge [12]. This mechanism is generally considered dominant for large globular analytes such as native proteins and protein complexes [13] [14].

- The Ion Evaporation Model (IEM): Proposed by Iribarne and Thomson, this mechanism posits that before a droplet reaches the ultimate size, the electric field at its surface becomes sufficiently intense to directly "push" or desorb solute ions into the gas phase [12]. This model is often invoked to explain the ionization of smaller analyte species.

The dominant pathway has significant implications for desolvation. CRM inherently involves the gradual removal of solvent from a confined droplet, while IEM involves the direct ejection of an ion from a liquid interface. Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations have provided atomistic-level insights into these processes. For instance, simulations of nanodisc ionization have revealed two distinct scenarios: an "at-center" process consistent with pure CRM, where the analyte remains in the droplet interior until final solvent evaporation, and an "off-center" process resembling a hybrid CRM/CEM model, where the analyte gradually migrates to the surface and is expelled [14]. The final morphology and solvation state of the gas-phase ion are heavily influenced by which pathway occurs.

Diagram 1: Two primary pathways for gas-phase ion formation from charged droplets during electrospray ionization.

Comparative Analysis of ESI-MS Interface Configurations

The ESI-MS interface, which bridges atmospheric pressure and the high vacuum of the mass analyzer, is a critical battlefield in the desolvation challenge. Its design directly influences how efficiently charged droplets are desolvated and how effectively the resulting gas-phase ions are transmitted without loss. Recent research has systematically evaluated different configurations, with a particular focus on ion utilization efficiency—defined as the proportion of analyte molecules in solution that are successfully converted to transmitted gas-phase ions [1].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of ESI-MS Interface Configurations

| Interface Configuration | Principle of Operation | Key Advantages | Inherent Desolvation Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single Emitter/Single Inlet Capillary [1] [4] | Electrospray plume is sampled by a single heated metallic capillary. | Simplicity and robustness; established methodology. | Significant ion losses on capillary walls; gas dynamic constraints limit sampling; requires high temperatures for complete desolvation. |

| Single Emitter/Multi-Inlet Capillary [1] | Multiple inlet capillaries arranged in a hexagonal pattern sample the spray. | Increased sampling area; higher total ion current transmission. | Potential for increased neutral background; complex alignment; may not proportionally increase analyte ion signal. |

| SPIN (Subambient Pressure Ionization) [1] | Emitter placed directly in the first vacuum stage, adjacent to an ion funnel. | Removes the limiting inlet capillary; high transmission efficiency of the ion funnel. | Requires careful control of vacuum pressure and temperature for desolvation; potential for electrical discharge. |

The performance of these interfaces has been quantitatively evaluated by measuring the total transmitted electrical current and correlating it with the analyte ion current observed in the mass spectrum [1]. These studies reveal that the SPIN-MS interface generally exhibits superior ion utilization efficiency compared to capillary-based inlets. A major factor contributing to this superiority is the more effective desolvation environment. In a standard capillary interface, a significant loss of analyte ions can occur after transmission through the inlet due to incomplete desolvation at common flow rates (e.g., >80% loss at 1.0 μL/min) [4]. The SPIN interface, by operating at a low-pressure environment and often employing a heated desolvation gas, promotes more complete and efficient solvent shedding from ions and charged clusters before they enter the focusing stages of the mass spectrometer [1].

Experimental Protocols for Interface Evaluation

To objectively compare the desolvation efficiency and overall performance of different ESI-MS interfaces, researchers employ standardized experimental protocols centered on current measurement and mass spectrometric detection.

This method provides a direct metric for evaluating interface performance.

- Solution Preparation: A standard peptide mixture (e.g., 1-10 μM each in 0.1% formic acid, 10% acetonitrile) is prepared to ensure a consistent and ionizable analyte stream.

- Interface Setup: The interface to be tested (single capillary, multi-capillary, or SPIN) is installed on a mass spectrometer equipped with a tandem ion funnel interface. The ESI emitter is positioned at the optimal distance (e.g., ~2 mm for capillary inlets, ~1 mm from the first ion funnel electrode for SPIN).

- Current Measurement: The gas-phase ions transmitted through the high-pressure ion funnel are collected using the low-pressure ion funnel as a charge collector, connected to a picoammeter. The average transmitted electric current is recorded.

- Mass Spectrometry Analysis: Simultaneously, mass spectra are acquired (e.g., over a 200-1000 m/z range). The total ion current (TIC) and extracted ion currents (EIC) for specific analytes are recorded.

- Data Correlation and Calculation: The transmitted electric current (a measure of all charged particles) is correlated with the MS-based ion currents (a measure of successfully desolvated analyte ions). The ratio provides a measure of the ion utilization efficiency, allowing for direct comparison between interfaces.

MD simulations offer a theoretical, atomistic view of the final stages of desolvation.

- System Construction: A pre-equilibrated protein or nanodisc is centered in a water box. Water molecules beyond a specified droplet radius (e.g., 2.5-8 nm) are deleted.

- Droplet Charging: Water molecules are randomly replaced with hydronium (H3O+) or sodium (Na+) ions to achieve a net charge near 90% of the droplet's Rayleigh limit.

- Simulation Execution: The system is energy-minimized and equilibrated. Production MD runs are conducted with a temperature ramp (e.g., from 370 K to 450 K) to facilitate solvent evaporation. Solvent molecules that move beyond a specified distance from the droplet center are periodically deleted to mimic evaporation.

- Proton Exchange (for H3O+ simulations): A specialized protocol is used to allow for Grotthuss diffusion of H3O+ and proton transfer to/from protein residues (e.g., Asp, Glu, His), dynamically altering protonation states during evaporation [13].

- Trajectory Analysis: The simulation trajectory is analyzed to determine the final composition of the gaseous ion (including residual water molecules), the pathway of ion formation (CRM, IEM, or hybrid), and the structural changes in the analyte.

Diagram 2: Core workflow for the experimental evaluation of ESI-MS interface ion utilization efficiency.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Essential Materials for ESI Desolvation and Interface Research

| Item / Reagent | Function in Experimental Research |

|---|---|

| Chemically Etched Fused Silica Emitters [1] | To produce stable nanoelectrospray plumes at low flow rates, which is essential for high ionization efficiency and reproducible results. |

| Tandem Ion Funnel Interface [1] | To efficiently focus and transmit ions through regions of intermediate pressure, minimizing losses and enabling accurate current measurements. |

| Standard Peptide Mixture (e.g., Angiotensin I, II) [1] | To provide a consistent and well-characterized model system for comparing ionization and transmission efficiency across different interface platforms. |

| Picoammeter [1] | To accurately measure the small electrical currents (transmitted charge) associated with the ion beam entering the mass spectrometer. |

| CHARMM36 Forcefield & TIP4P/2005 Water Model [13] [14] | The standard molecular models used in MD simulations to realistically simulate the behavior of proteins, lipids, and water during the desolvation process. |

| GROMACS-2022.3 MD Software [13] | A high-performance molecular dynamics package used to run the complex simulations of charged droplet evaporation and ion formation. |

The challenge of transforming charged droplets into pristine gas-phase ions remains a central focus in the advancement of ESI-MS technology. The evidence indicates that no single solution is optimal for all scenarios. While the SPIN-MS interface demonstrates superior ion utilization efficiency by circumventing the limitations of inlet capillaries, capillary-based systems remain prevalent and functionally useful. The choice between interface configurations represents a trade-off between ultimate sensitivity, robustness, and operational complexity. The ongoing research, employing both rigorous experimental current measurements and detailed molecular dynamics simulations, continues to refine our understanding of the fundamental desolvation process. This work, particularly when framed within comparative studies of interface design, provides a critical roadmap for developing next-generation mass spectrometry instrumentation with enhanced sensitivity for researchers and drug development professionals.

How Inlet Capillary Design Governs Ion Sampling

In electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS), the journey of an ion from solution to detection is fraught with potential losses. The design of the atmospheric pressure interface (API), and the inlet capillary in particular, is a critical determinant of the sensitivity and efficiency of this process. The capillary serves as the gateway, governing the initial sampling of ions from the atmospheric pressure ion source into the first vacuum stage of the mass spectrometer. Its configuration directly influences the efficiency of ion transmission, a parameter that is paramount for detecting trace-level analytes in complex mixtures such as those encountered in drug development.

This guide objectively compares the performance of different inlet capillary designs, contextualized within a broader research thesis that investigates single emitter versus multi-inlet configurations. We summarize experimental data and provide detailed methodologies to offer scientists a clear understanding of how capillary design governs ion sampling.

Capillary Design Configurations and Performance Metrics

The pursuit of higher sensitivity in ESI-MS has led to the development of several innovative inlet capillary designs. These designs aim to overcome the fundamental limitation of conventional interfaces: the significant loss of ions before they even reach the mass analyzer.

Prevalent Inlet Capillary Designs

- Single Inlet Capillary: This is the conventional configuration, featuring a single metal or glass capillary (typically 4-8 cm long, with an internal diameter of ~430-490 µm) heated to aid droplet desolvation. The ESI emitter is positioned ~2 mm in front of this inlet [1] [5].

- Multi-Capillary Inlet: This design consists of multiple inlet capillaries arranged in a pattern (e.g., hexagonal or linear) that matches an array of ESI emitters. For example, one configuration used seven capillaries (490 µm i.d.) in a hexagonal pattern, while another used a linear array of nine inlets (490 µm i.d.) spaced 1.0 mm apart [1] [5].

- Subambient Pressure Ionization with Nanoelectrospray (SPIN) Interface: A paradigm-shifting design that removes the inlet capillary constraint altogether. Here, the ESI emitter is placed directly inside the first vacuum chamber (at ~20 Torr), adjacent to the entrance of an electrodynamic ion funnel. This setup eliminates the pressure drop and ion losses associated with a narrow atmospheric pressure orifice [1].

Quantitative Performance Comparison

The following table summarizes key experimental findings that directly compare the ion transmission performance of these different interface configurations.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of ESI-MS Interface Configurations

| Interface Configuration | Key Experimental Findings | Reported Sensitivity Enhancement | Primary Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single Inlet Capillary | Serves as a baseline for comparison. Limited by radial expansion of the gas jet and turbulent ion scattering at the capillary exit [15]. | Baseline | Standard, widely available design. |

| Multi-Capillary Inlet | Enabled higher total ion current transmission from multi-emitter arrays. Coupling a 19-emitter array with a 19-capillary inlet showed significant gains [5]. | ~11-fold average signal increase for peptides from spiked proteins in human plasma digest; ~7-fold increase in LC peak S/N [5]. | Extends nanoESI sensitivity benefits to higher LC flow rates. |

| SPIN Interface | Exhibited greater overall ion utilization efficiency than capillary-based inlets. Highest transmitted ion current measured with a SPIN/emitter array combination [1]. | Highest transmitted ion current measured; greater ion utilization efficiency [1]. | Eliminates inlet capillary losses, superior for coupling with bright ion sources like emitter arrays. |

Experimental Protocols for Ion Transmission Analysis

To generate the comparative data presented above, researchers employ rigorous and reproducible experimental protocols. The core methodology involves measuring the total electric current of ions transmitted through the interface and correlating it with the abundance of specific analyte ions observed in the mass spectrum.

Core Methodology: Ion Utilization Efficiency

The ion utilization efficiency is a key metric defined as the proportion of analyte molecules in solution that are successfully converted to gas-phase ions and transmitted through the MS interface [1]. The general protocol involves:

- Solution Preparation: A standard peptide mixture (e.g., angiotensin I, neurotensin, bradykinin) is prepared in a standard solvent (e.g., 0.1% formic acid in 10% acetonitrile) at known concentrations (e.g., 1 µM and 100 nM for each peptide) [1].

- Ion Current Measurement:

- Transmitted Electric Current: The gas-phase ions transmitted through the high-pressure ion funnel are collected using a picoammeter. This measures the total charge entering the MS vacuum system [1].

- Total Ion Current (TIC) & Extracted Ion Current (EIC): The mass spectrometer records the total ion abundance (TIC) and the abundance for specific analyte ions (EIC) in the mass spectrum.

- Data Correlation: The transmitted electric current is correlated with the observed TIC and EIC. A higher ratio of MS signal to transmitted current indicates a greater proportion of fully desolvated analyte ions versus residual solvent clusters, reflecting higher ion utilization efficiency [1].

Experimental Setup for Interface Comparison

A typical experimental setup for comparing interfaces involves a time-of-flight (TOF) mass spectrometer where the standard interface has been replaced by a tandem ion funnel interface. This allows for the systematic evaluation of different inlet configurations [1] [5].

Diagram: Experimental Workflow for Comparing Inlet Capillary Designs

The Impact of Gas Dynamics on Ion Sampling

The performance of an inlet capillary is not solely defined by its geometry. The behavior of the gas expanding through and exiting the capillary creates a complex aerodynamic environment that profoundly impacts ion trajectories.

Gas Flow Phenomena in the Inlet

Upon exiting the capillary into the vacuum, the gas forms a highly underexpanded supersonic free jet. This jet is characterized by a complex shock structure, including a Mach disk (a strong normal shock) and barrel-shaped oblique shocks [15]. Computational fluid dynamics simulations, particularly Large Eddy Simulation (LES), reveal that this flow is highly turbulent and transient, generating complicated vortical structures [15].

Without effective ion confinement, these shock waves and turbulent vortices utterly scatter ion clouds, leading to massive losses. Studies indicate that incomplete droplet desolvation in the low-temperature "zone of silence" within these shocks can cause ion losses of up to 80% [15].

Ion Focusing Countermeasures

To mitigate these losses, modern API designs incorporate ion focusing devices downstream of the capillary exit:

- Ion Funnel: An efficient device for capturing and focusing scattered ions. It uses radially convergent electrodes with an axial DC gradient to guide ions through a narrow orifice into the next vacuum stage, effectively counteracting turbulent dispersion [1] [15].

- S-Lens: A stacked-ring ion guide that collimates ion clouds by progressively enlarging the gaps between ring electrodes. However, the lack of axial DC propulsion can create deeper pseudopotential traps that may obstruct ion transport in the absence of a steady axial gas flow [15].

The effectiveness of these devices is strongly influenced by the nature of the gas flow from the inlet capillary, underscoring the integral relationship between capillary design and subsequent ion optics.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Ion Sampling Studies

| Item | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| Standard Peptide Mix | A mixture of well-characterized peptides (e.g., Angiotensin I, Neurotensin, Bradykinin) used as a model system to evaluate and compare interface performance under standardized conditions [1] [5]. |

| Chemically Etched Fused Silica Emitters | NanoESI emitters created by chemical etching, providing a non-tapered internal geometry that is less prone to clogging and allows stable operation at low flow rates (e.g., 20 nL/min) [1] [5]. |

| Tandem Ion Funnel Interface | A modified MS interface that replaces the standard skimmer with two consecutive electrodynamic ion funnels operating at different pressures (e.g., 18 Torr and 1.3 Torr) to efficiently capture and transmit ions from high-gas-load inlets like multi-capillary arrays [1] [5]. |

| Picoammeter | An instrument capable of precisely measuring the very small electric currents (on the order of picoamperes) corresponding to the total charge of ions transmitted through the interface [1]. |

The design of the inlet capillary is a principal factor in governing ion sampling efficiency in ESI-MS. Experimental evidence clearly demonstrates that moving beyond the conventional single inlet design can yield substantial gains in sensitivity. Multi-capillary inlets effectively harness the increased ion current produced by multi-emitter arrays, making the benefits of nanoESI accessible to higher-flow-rate LC separations. The SPIN interface, by fundamentally rethinking the pressure regime of ionization, offers a potentially superior pathway for maximizing ion utilization. The optimal choice of inlet design depends on the specific application, but it is undeniable that innovations in this critical region of the mass spectrometer continue to be a primary driver for achieving lower detection limits and more robust analyses.

Advanced Interface Designs: From Multi-Capillary Inlets to Subambient Pressure Sources

Performance Comparison of ESI-MS Interface Configurations

The performance of the single emitter/single inlet capillary interface is best understood when compared directly with advanced alternative designs. The following table summarizes key quantitative comparisons from controlled experimental studies.

Table 1: Quantitative comparison of ESI-MS interface configurations using peptide standards

| Interface Configuration | Sensitivity Improvement (Factor) | Ion Utilization Efficiency | Key Characteristics | Experimental Basis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single Emitter/Single Inlet Capillary | Baseline (1x) | Lower than SPIN interfaces [1] | Conventional heated capillary; ~2-3 mm emitter-to-inlet distance [1] | 1 μM peptide mixture; 490 μm i.d. capillary heated to 120°C [1] |

| Single Emitter/Multi-Inlet Capillary | Not quantified | Lower than SPIN interfaces [1] | Seven inlet capillaries in hexagonal pattern [1] | Same peptide mixture and MS platform as single inlet [1] |

| SPIN-MS (Single Emitter) | >10x [16] | ~50% at 50 nL/min flow rate [16] | Emitter in vacuum (19-22 Torr); heated CO₂ desolvation gas [1] | 9-peptide mixture; emitter adjacent to ion funnel in vacuum [16] |

| SPIN-MS (Emitter Array) | >10x [16] | Highest of configurations tested [1] | 4, 6, or 10 emitters with individualized sheath gas [16] | 9-peptide mixture; 19-emitter array showed 11x signal increase for plasma peptides [5] |

Experimental Protocols for Interface Evaluation

Ion Utilization Efficiency Measurement

The overall performance of an ESI-MS interface is quantitatively evaluated through its ion utilization efficiency—the proportion of analyte molecules in solution converted to gas-phase ions and transmitted through the interface to the detector [1].

Sample Preparation:

- Prepare stock solutions (1 mg/mL) of standard peptides (angiotensin I, angiotensin II, bradykinin, etc.) in 0.1% formic acid in 10% acetonitrile/water [1]

- Create peptide mixture with final concentration of 1 μM for each peptide [16]

- Utilize ESI solvent consisting of 0.1% formic acid in 10% acetonitrile and deionized water [1]

Interface Configurations:

- Single inlet capillary: Use stainless steel capillary (7.6 cm long, 490 μm i.d.) heated to 120°C [1]

- Multi-capillary inlet: Arrange seven capillaries (7.6 cm long, 490 μm i.d.) in hexagonal pattern [1]

- SPIN interface: Position emitter inside first vacuum region (19-22 Torr) adjacent to ion funnel [1]

Measurement Procedure:

- Position ESI emitter on 3-axis translation stage approximately 2 mm from capillary inlet [1]

- Infuse solutions using syringe pump with ESI voltages applied via stainless steel union [1]

- Acquire mass spectra over 200-1000 m/z range in positive ion mode [1]

- Measure transmitted gas-phase ion current using picoammeter connected to ion funnel [1]

- Correlate electric current measurements with observed ion abundance in mass spectra [1]

SPIN-MS Interface Methodology

The Subambient Pressure Ionization with Nanoelectrospray (SPIN) interface fundamentally reimagines ion transmission by eliminating atmospheric pressure introduction.

Key Modifications:

- Place ESI emitter in first vacuum chamber (10-30 Torr) adjacent to electrodynamic ion funnel [16]

- Apply heated CO₂ desolvation gas (~160°C) with controlled flow rate [1]

- Provide additional CO₂ sheath gas around ESI emitter to ensure electrospray stability [1]

- Bias cylindrical outlet (counter electrode) 50V higher than front plate of high-pressure ion funnel [1]

Emitter Fabrication:

- Chemically etch fused silica capillaries (150 μm o.d., 10 μm i.d.) to create tapered emitters [1]

- For emitter arrays: arrange 4, 6, or 10 emitters with individualized coaxial sheath gas capillaries [16]

- Prevent inner wall etching by pumping water through emitter array during HF etching process [16]

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential materials and reagents for ESI-MS interface evaluation

| Item | Specification | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Fused Silica Capillaries | 150 μm o.d., 10 μm i.d. (Polymicro Technologies) [1] | ESI emitter fabrication via chemical etching |

| Standard Peptides | Angiotensin I/II, bradykinin, neurotensin, etc. (Sigma-Aldrich) [1] | Performance standards for sensitivity comparison |

| Solvent System | 0.1% formic acid in 10% acetonitrile/water [1] | ESI solvent for peptide analysis |

| Syringe Pump | Harvard Apparatus Model 22 [1] | Precise solution infusion at nL/min to μL/min rates |

| High Voltage Power Supply | Ultravolt HV-RACK-4-250-00229 [1] | Electrospray voltage application (typically 2-4 kV) |

| Chemical Etching Solution | 49% hydrofluoric acid (Fisher Scientific) [16] | Tapered emitter formation for nanoESI |

Experimental Workflow Visualization

The diagram below illustrates the key experimental workflow for comparing single emitter/single inlet capillary performance against advanced interface configurations.

The single emitter/single inlet capillary interface remains the conventional workhorse of ESI-MS despite its demonstrated limitations in ion transmission efficiency. Quantitative comparisons reveal that advanced configurations—particularly the SPIN interface with multi-emitter arrays—can provide order-of-magnitude sensitivity improvements by fundamentally addressing ion losses at the atmosphere-vacuum boundary. These performance differences are quantitatively measurable using standardized peptide mixtures and controlled current measurement protocols, providing researchers with clear methodological pathways for interface evaluation and selection.

In the field of mass spectrometry and ion beam applications, the efficient transfer of ions from atmospheric pressure to high vacuum represents a fundamental challenge. This process is notoriously inefficient, creating a significant bottleneck for sensitivity and detection limits in analytical applications. The research community has pursued two primary pathways to address this challenge: single-emitter sources that optimize ionization at the point of origin, and multi-capillary inlet systems that expand the sampling area and revolutionize ion transmission efficiency. This guide provides an objective comparison of these approaches, focusing on the transformative impact of multi-capillary inlet design as demonstrated through experimental data and performance metrics.

The fundamental limitation stems from the stark pressure difference between atmospheric pressure (where ionization techniques like electrospray ionization operate) and the high-vacuum environment required for mass analysis. Traditional single-inlet interfaces struggle with fluid dynamics effects that lead to significant ion losses. Multi-capillary inlets address this core problem by dramatically expanding the effective sampling area, thereby capturing a greater proportion of generated ions while maintaining the required pressure differential through distributed gas flow [17] [18].

Fundamental Principles and Theoretical Framework

The Multi-Capillary Operating Principle

Multi-capillary inlet systems function through an array of parallel capillary tubes, typically constructed from stainless steel or other durable materials, which serve as the initial transition stage from atmosphere to vacuum. Unlike single capillary inlets that create a restrictive sampling bottleneck, the multi-capillary approach distributes the gas and ion load across multiple pathways. Each capillary tube in the array acts as a separate conductance limit, allowing the total sampling area to increase proportionally with the number of capillaries while maintaining the pressure gradient necessary for vacuum integrity [17].

The innovation extends beyond mere parallelization. The geometry and arrangement of the capillary array are engineered to optimize the gas dynamics within the interface. As ions travel through the capillaries with the expanding gas stream, they experience collisional focusing effects that help maintain beam coherence. Subsequent stages, typically incorporating electrodynamic ion funnels, then capture this expanded ion stream and focus it efficiently toward the high-vacuum regions [18]. This combination addresses both the sampling efficiency limitation of single inlets and the transmission losses that occur in the intermediate pressure regions.

Comparative Physical Principles

The theoretical advantage of multi-capillary systems becomes evident when examining the fundamental limitations of single inlet designs. Single capillary inlets create a severe sampling restriction because the ionization region typically extends over a much larger area than the inlet orifice can effectively sample. This geometric mismatch results in the majority of generated ions never entering the transfer interface. Furthermore, space charge effects within the confined capillary volume cause ion repulsion and significant losses, particularly at higher ion currents [19].

Multi-capillary inlets address these limitations through several complementary mechanisms. The expanded sampling area captures ions from a larger region of the ionization plume, reducing the geometric mismatch. The distribution of gas flow across multiple capillaries reduces the velocity and turbulence within each individual pathway, minimizing ion dispersion. Additionally, the distributed nature of the system mitigates space charge effects by providing multiple, lower-density pathways rather than a single, high-density bottleneck [18]. These principles collectively explain the dramatic improvements in transmission efficiency observed experimentally.

Experimental Comparisons and Performance Data

Direct Performance Comparison

Controlled experimental evaluations demonstrate the significant advantages of multi-capillary inlet systems over traditional single-capillary designs. The data reveal substantial improvements across multiple performance metrics that directly impact analytical sensitivity and detection capabilities.

Table 1: Quantitative Performance Comparison of Inlet Designs

| Performance Metric | Single Capillary + Ion Funnel | Multi-Capillary + Ion Funnel | Standard Orifice-Skimmer |

|---|---|---|---|

| Relative Transmission Efficiency | 1x (baseline) | 7x higher [18] | 23x lower than multi-capillary [18] |

| Overall Ion Transmission Efficiency | Not reported | ~10% [18] | Significantly lower |

| Overall Detection Efficiency (from solution) | Not reported | 3-4% [18] | Not reported |

| Space Charge Limit | Limited | Up to 40 nA current transmission [19] | More limited |

| Operational Robustness | Standard | More robust ESI operation [18] | Standard |

Experimental Methodologies for Performance Evaluation

The comparative data presented in Table 1 were generated through carefully controlled experimental protocols. A standard methodology for evaluating inlet performance involves:

Interface Construction: Multi-capillary inlets are typically fabricated from an array of thin-wall stainless steel tubes (often seven capillaries) soldered into a central hole of a cylindrical heating block. The heating block facilitates desolvation of charged droplets [18]. Single capillary interfaces use an identical material but with a single orifice of appropriate diameter.

Ionization Source Configuration: Electrospray ionization sources are operated under identical conditions for both inlet types, typically using standard compounds such as reserpine or minoxidil to generate stable ion currents [17] [18]. Solution concentrations are carefully controlled to enable accurate detection efficiency calculations.

Transmission Measurement: Ion currents are measured at multiple points in the vacuum interface using Faraday cups or similar detection methods. Comparison of currents at different stages allows researchers to calculate transmission efficiency through specific components [18].

Mass Spectrometric Validation: Final validation is performed using mass spectrometric detection to confirm that the transmitted ions maintain mass spectral integrity without degradation or additional contamination [19].

Dynamic Range Assessment: Experiments measuring signal response across concentration ranges demonstrate the impact of improved transmission on dynamic range, a critical analytical parameter [18].

Technical Implementation and Optimization

Critical Design Parameters

Successful implementation of multi-capillary inlet technology requires careful optimization of several key parameters that govern overall performance:

Capillary Array Geometry: The number, diameter, and arrangement of capillaries must balance total sampling area with gas load and pressure differential management. Seven-capillary arrays have demonstrated excellent performance while maintaining manageable gas loads [18].

Thermal Management: Precision temperature control of the heated block surrounding the capillary array is crucial for efficient desolvation without promoting thermal degradation of analytes [17] [18].

Material Selection: Stainless steel capillaries provide durability and manufacturing precision, with proper surface treatments to minimize adsorption and catalytic effects [17].

Ion Funnel Integration: The electrodynamic ion funnel following the capillary array must be optimized to capture the expanded ion stream efficiently, typically requiring specific RF and DC field configurations matched to the multi-capillary output [18].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Materials for Multi-Capillary Inlet Experimentation

| Component/Reagent | Function in Experimental Setup | Typical Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Stainless Steel Capillary Tubes | Forms the multi-capillary array structure | Thin-wall, precise internal diameter [18] |

| Heating Block Assembly | Provides controlled thermal desolvation | Cylindrical design with precision temperature control [18] |

| Electrodynamic Ion Funnel | Focuses and transmits ions after capillary stage | RF/DC field capability, pressure-matched [18] |

| Test Analytes (Reserpine, Minoxidil) | Performance evaluation standards | High purity, known ionization characteristics [17] |

| ESI Calibration Solutions | System performance validation | Often includes dodecyltrimethylammonium bromide [17] |

Implications for Drug Development and Analytical Science

The enhanced performance of multi-capillary inlet systems has significant implications for pharmaceutical research and analytical science, particularly in applications where sensitivity limitations restrict progress.

In drug development, the improved ion transmission directly enhances the detection of low-abundance metabolites, potentially identifying toxic species that might otherwise escape detection. This capability aligns with growing interest in advanced toxicity screening approaches, including computational models of drug-induced liver injury that require comprehensive metabolite profiling [20]. The expanded dynamic range also facilitates quantitative analysis across broader concentration ranges without requiring sample dilution or concentration.

For researchers studying complex biological systems, the multi-capillary advantage enables more comprehensive profiling of limited samples. The technology's compatibility with various ionization sources makes it particularly valuable for hyphenated techniques where comprehensive molecular characterization is essential. When integrated with advanced separation techniques, the multi-capillary interface supports the identification of trace components in complex matrices, a common challenge in pharmaceutical impurity profiling and biomarker discovery.

The experimental evidence clearly demonstrates that multi-capillary inlet design represents a substantial advancement over single inlet systems for ion transmission from atmospheric pressure to high vacuum. With demonstrated improvements of 7-fold in transmission efficiency compared to single capillary systems with equivalent ion funnel technology, and 23-fold improvement over traditional orifice-skimmer interfaces, the multi-capillary approach effectively addresses the fundamental sampling limitation that has long constrained analytical sensitivity [18].

Future developments in this field will likely focus on further optimization of capillary array geometries, advanced materials to reduce surface interactions, and more sophisticated integration with subsequent focusing elements. Additionally, the application of these principles to specialized areas such as ion beam deposition and portable instrumentation represents promising research directions. As analytical challenges continue to evolve toward more complex samples and lower detection limits, the expanded sampling area provided by multi-capillary technology establishes a foundation for the next generation of high-sensitivity mass spectrometry applications across pharmaceutical development and biological research.