Specific vs. Non-Specific Protein Quantification by UV-Vis: A Guide for Accurate Analysis in Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on selecting and applying UV-Vis spectroscopy methods for protein quantification.

Specific vs. Non-Specific Protein Quantification by UV-Vis: A Guide for Accurate Analysis in Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on selecting and applying UV-Vis spectroscopy methods for protein quantification. It covers the foundational principles of specific and non-specific assays, detailed methodologies including BCA, Bradford, and direct UV absorbance, and practical troubleshooting for common interferences. A comparative validation of techniques is presented to guide method selection for diverse applications, from HBOC characterization to biopharmaceutical quality control, ensuring accurate and reliable protein concentration data.

Protein Quantification Fundamentals: Understanding Specificity, Interference, and the Beer-Lambert Law

Core Principles of UV-Vis Spectrometry and the Beer-Lambert Law

Theoretical Foundation

UV-Vis spectrometry is a fundamental analytical technique used to measure the absorption of ultraviolet and visible light by a substance. When light passes through a sample, photons can be absorbed by molecules, promoting electrons to higher energy states. The extent of this absorption provides quantitative information about the sample's concentration and qualitative insights into its molecular properties [1].

The relationship between light absorption and sample properties is mathematically described by the Beer-Lambert Law (also known as Beer's Law). This principle states that the absorbance of light by a solution is directly proportional to the concentration of the absorbing species and the path length the light travels through the sample [2] [3]. The fundamental equation is expressed as:

A = εcl

Where:

- A is the absorbance (unitless)

- ε is the molar absorptivity or molar extinction coefficient (M⁻¹cm⁻¹)

- c is the concentration of the absorbing species (M)

- l is the path length of light through the sample (cm) [3] [1]

The relationship between transmittance and absorbance is logarithmic, defined as:

A = log₁₀(I₀/I)

Where I₀ is the incident light intensity and I is the transmitted light intensity [2] [3]. This logarithmic relationship means that absorbance increases as transmittance decreases, as shown in the table below [2]:

| Absorbance | Transmittance |

|---|---|

| 0 | 100% |

| 1 | 10% |

| 2 | 1% |

| 3 | 0.1% |

| 4 | 0.01% |

| 5 | 0.001% |

The molar absorption coefficient (ε) is a substance-specific property that measures how strongly a compound absorbs light at a particular wavelength. Higher values indicate stronger absorption capabilities [2].

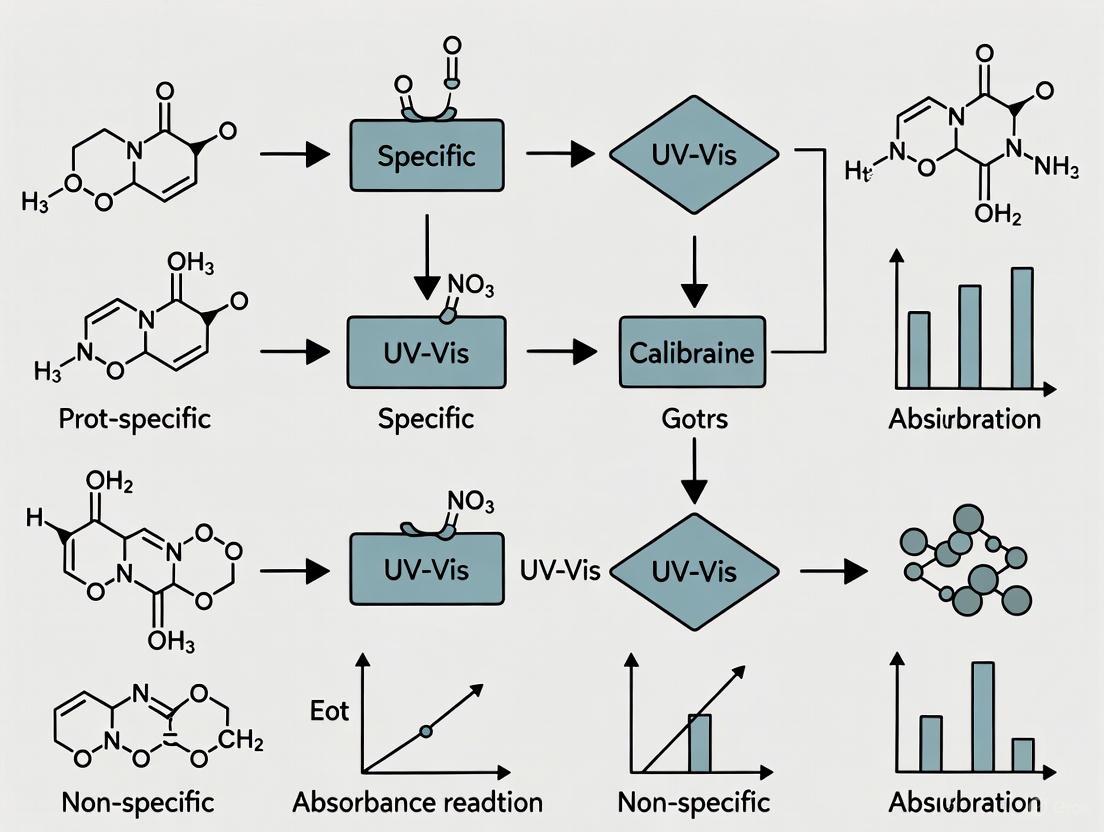

Visual representation of the Beer-Lambert Law principle, showing how light attenuation through a sample relates to concentration and path length.

Protein Quantification Methods: Specific vs. Non-Specific

In protein analysis, UV-Vis spectrometry methods can be categorized as specific or non-specific based on their mechanism of detection and susceptibility to interference.

Direct UV Absorbance Methods

The most direct application of UV-Vis spectrometry for protein quantification utilizes the intrinsic absorbance properties of aromatic amino acids. Proteins absorb UV light primarily at 280 nm due to the presence of tryptophan, tyrosine, and phenylalanine residues. These aromatic amino acids act as intrinsic chromophores, with conjugated double bonds that absorb UV light [4] [1]. The far-UV method (205 nm) measures peptide bond absorption and is less affected by protein amino acid composition [5].

Advantages of direct UV methods include speed, simplicity, non-destructiveness, and no requirement for additional reagents [4] [1]. Limitations include interference from compounds absorbing at similar wavelengths (particularly nucleic acids), dependence on protein aromatic amino acid content, and limited dynamic range [4] [1].

Colorimetric Protein Assays

Colorimetric methods rely on chemical reactions that produce colored complexes proportional to protein concentration:

- BCA (Bicinchoninic Acid) Method: Under alkaline conditions, peptide bonds reduce Cu²⁺ to Cu⁺, which chelates with BCA to form a purple complex measurable at 562 nm [4] [6].

- Bradford (Coomassie Brilliant Blue) Method: The dye shifts from cationic (red) to anionic (blue) form when bound to proteins, particularly basic amino acids (lysine, arginine), with maximum absorption at 595 nm [4].

- Lowry Method: Combines the Biuret reaction (copper binding to peptide bonds) with the Folin-Ciocalteau reagent reaction with tyrosine and tryptophan residues [5].

Comparative Experimental Data

Method Performance Across Different Sample Types

Experimental comparisons reveal significant variations in performance between quantification methods depending on sample composition:

Table 1: Comparison of protein concentration results (μg/μL) for snake venoms using different quantification methods [7]

| Method | Naja ashei (Elapids) | Agkistrodon contortrix (Viperids) |

|---|---|---|

| BCA | 289.27 | 201.38 |

| Bradford | 314.60 | 184.70 |

| 2-D Quant Kit | 180.10 | 184.90 |

| Qubit | 125.67 | 172.33 |

| NanoDrop (Direct UV) | 852.00 | 230.40 |

Table 2: Advantages and limitations of major protein quantification methods [4] [1] [5]

| Method | Mechanism | Detection Range | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct UV (280 nm) | Aromatic amino acid absorption | ~0.1-100 mg/mL | Fast, non-destructive, no reagents | Nucleic acid interference, variable extinction coefficients |

| BCA | Cu²⁺ reduction by peptide bonds | 20-2000 μg/mL | High sensitivity, compatible with detergents | Affected by reducing agents, chelators |

| Bradford | Protein-dye binding | 1-100 μg/mL | Rapid, simple protocol | Variable response to different proteins, detergent interference |

| Lowry | Biuret reaction + Folin-Ciocalteau | 1-100 μg/mL | High sensitivity, precision | Multiple steps, reagent instability |

The data demonstrates that method selection critically depends on sample composition. For example, Naja ashei venom shows dramatically different measured concentrations across methods (125.67-852.00 μg/mL), while Agkistrodon contortrix venom results are more consistent (172.33-230.40 μg/mL) [7]. This variability stems from differences in venom protein composition between species, highlighting the importance of matching method to sample characteristics.

Hemoglobin Quantification Study

A 2024 systematic comparison of UV-Vis spectroscopy methods for hemoglobin (Hb) quantification identified the sodium lauryl sulfate Hb (SLS-Hb) method as optimal due to its specificity, ease of use, cost-effectiveness, and safety compared to cyanmethemoglobin-based methods [6]. The study emphasized that method selection is often driven by tradition rather than thorough assessment, potentially compromising accuracy in HBOC (hemoglobin-based oxygen carriers) characterization.

Experimental Protocols

Direct UV Absorption at 280 nm

Principle: Measures intrinsic UV absorption of aromatic amino acids in proteins [1].

Procedure:

- Turn on UV-Vis spectrophotometer and allow lamp to warm up for 15-30 minutes

- Prepare appropriate buffer blank matching sample solvent

- Zero instrument with blank at 280 nm

- Dilute protein sample to fall within linear absorbance range (0.1-1.0 AU)

- Measure sample absorbance at 280 nm

- Calculate concentration using Beer-Lambert Law: c = A/(ε·l)

Critical Considerations:

- Use quartz cuvettes for UV measurements [1]

- Ensure absorbance values remain in linear range (<1.0 AU)

- Apply correction for nucleic acid contamination when necessary [5]

- Use appropriate molar extinction coefficient for target protein

BCA Assay Protocol

Principle: Peptide bonds reduce Cu²⁺ to Cu⁺ under alkaline conditions, forming purple complex with bicinchoninic acid [4] [6].

Procedure:

- Prepare BCA working reagent (50:1 ratio of Reagent A:B)

- Add 25 μL standard or unknown protein samples to microplate wells

- Add 200 μL BCA working reagent to each well

- Mix plate thoroughly on plate shaker for 30 seconds

- Incubate at 37°C for 30 minutes

- Measure absorbance at 562 nm using plate reader

- Generate standard curve and calculate unknown concentrations

Modifications for Different Samples:

- For membrane proteins: Include detergents compatible with assay [4]

- For samples with reducing agents: Use alternative methods or remove interferents

General workflow for protein concentration analysis using UV-Vis spectrometry, applicable to both direct and colorimetric methods.

Limitations and Practical Considerations

Beer-Lambert Law Deviations

The Beer-Lambert Law operates under several assumptions that may not hold in practical applications:

Chemical Deviations:

- High Concentration Effects: At elevated concentrations (>0.01 M), intermolecular distances decrease, altering absorption properties through molecular interactions [8] [9]

- Chemical Equilibria: Sample dissociation, association, or pH-dependent changes affect absorption characteristics [8]

- Solvent Effects: Refractive index changes with concentration violate the law's assumptions at high concentrations [9]

Instrumental Deviations:

- Stray Light: Imperfect monochromators allow non-absorbed wavelengths to reach detector [8]

- Polychromatic Light: Use of bandwidths exceeding absorption peak width violates monochromatic light assumption [8]

- Fluorescence: Emitted light from samples increases apparent transmission [8]

Optical Effects:

- Light Scattering: Particulate matter or turbid samples scatter rather than absorb light [8]

- Reflection Losses: Significant at cuvette interfaces, particularly with high refractive index materials [9]

- Interference Effects: Wave nature of light causes interference patterns in thin films [9]

Protein-Specific Considerations

The accuracy of protein quantification depends heavily on sample composition and properties:

Amino Acid Composition: Proteins with atypical aromatic amino acid content yield inaccurate results with direct UV methods [1] [5].

Buffer Compatibility: Common buffer components (detergents, reducing agents, chelators) interfere with colorimetric assays [4] [5].

Protein Conformation: Denaturation or aggregation alters absorption characteristics and reagent accessibility [5].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key reagents and materials for protein quantification by UV-Vis spectrometry

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Quartz Cuvettes | Sample holder for UV measurements | Transparent down to 190 nm; required for direct UV methods [1] |

| BCA Assay Kit | Colorimetric protein quantification | Includes BCA reagents, copper solution, protein standards [6] |

| Bradford Reagent | Coomassie dye-based quantification | Compatible with most salts; incompatible with detergents [4] [7] |

| UV-Transparent Buffers | Sample dissolution and dilution | PBS, Tris-HCl, bicarbonate; avoid UV-absorbing additives [1] |

| Protein Standards | Calibration curve generation | BSA commonly used; match standard to sample when possible [5] |

| Microplate Readers | High-throughput absorbance measurement | Enable multiple sample processing; 96-well and 384-well formats [6] |

UV-Vis spectrometry, grounded in the Beer-Lambert Law, provides versatile approaches for protein quantification, with each method offering distinct advantages for specific applications. Direct UV methods excel for pure protein samples where extinction coefficients are known, while colorimetric assays like BCA and Bradford offer enhanced sensitivity for complex mixtures. Method selection must consider the trade-offs between specificity, sensitivity, and susceptibility to interference. Researchers should validate their chosen method with appropriate standards and be mindful of the Beer-Lambert Law's limitations, particularly with complex biological samples. The continuing development of instrumentation and reagent kits enhances the precision and reliability of these fundamental analytical techniques in both research and development settings.

Defining Specific vs. Non-Specific Protein Quantification Methods

Accurate protein quantification is a cornerstone of biochemical research, molecular biology, and biopharmaceutical development. The ability to precisely determine protein concentration is essential for experiments ranging from enzyme kinetics and drug binding studies to quality control of therapeutic proteins [1] [10]. Protein quantification methods can be broadly categorized into two groups based on their mechanism: specific methods and non-specific methods. Specific quantification methods determine the concentration of a particular protein of interest within a mixture, often by leveraging unique structural or binding characteristics. In contrast, non-specific methods measure the total protein content in a sample without distinguishing between different protein types [11] [12]. The fundamental distinction lies in what is being measured: specific methods identify a target protein based on specific amino acids or immunoaffinity, while non-specific methods respond to general protein properties like peptide bonds or overall composition.

Understanding this dichotomy is crucial for researchers selecting the appropriate analytical technique. The choice between specific and non-specific quantification impacts the accuracy, reliability, and interpretation of experimental results, particularly in complex biological matrices where multiple proteins coexist [13]. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of these methodologies, focusing on their principles, applications, and performance characteristics to inform method selection in research and development settings.

Principles of Specific Protein Quantification

Specific protein quantification methods target unique molecular features that allow them to distinguish a particular protein from others in a mixture. These techniques are indispensable when researchers need to measure a specific protein's concentration amid a complex background of other proteins, such as in cell lysates, serum, or purification fractions.

UV Absorbance at 280 nm (A280)

The A280 method represents a widely used specific quantification approach that leverages the innate ultraviolet absorption properties of aromatic amino acids. This technique is based on the Beer-Lambert law (A = εcl, where A is absorbance, ε is the molar absorptivity, c is concentration, and l is path length) and depends on the presence of tryptophan and tyrosine residues in the target protein [1] [14]. These aromatic side chains absorb UV light intensely at 280 nm, enabling direct concentration measurement without additional reagents. The molar absorptivity (ε) at 280 nm can be accurately predicted from a protein's amino acid sequence, making this method particularly valuable for purified proteins [14].

The specificity of A280 quantification arises from the varying content of aromatic amino acids in different proteins. Since the extinction coefficient is sequence-dependent, this method effectively provides a specific measurement for a given protein with a known amino acid composition [1] [15]. However, this specificity also represents a limitation, as proteins lacking tryptophan or tyrosine cannot be quantified using standard A280 measurements. For such proteins, alternative specific methods like A205 absorbance (which measures peptide bonds) may be employed [14].

Immunoassay-Based Methods

Immunoassays, particularly Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assays (ELISA), represent another category of specific protein quantification. These methods utilize the high specificity of antibody-antigen interactions to selectively capture and quantify a target protein [10]. In a typical sandwich ELISA, the protein of interest is captured between a surface-immobilized primary antibody and a secondary antibody conjugated to a detection enzyme. This setup provides exceptional specificity, enabling measurement of specific proteins even in highly complex mixtures like blood plasma or cell lysates [10].

The specificity of immunoassays stems from the molecular recognition properties of antibodies, which can be engineered to distinguish subtle differences in protein structure, including post-translational modifications, isoforms, and conformers [11]. This high degree of specificity makes immunoassays particularly valuable in diagnostic applications and biopharmaceutical development where particular protein variants must be quantified amid a background of similar molecules.

Principles of Non-Specific Protein Quantification

Non-specific protein quantification methods measure total protein content in a sample without distinguishing between different protein types. These approaches target chemical features common to most proteins, making them suitable for applications where overall protein concentration rather than specific protein identity is of interest.

Colorimetric Assay Methods

Colorimetric assays represent the most commonly used non-specific quantification approaches, relying on chemical reactions that produce a color change proportional to total protein concentration.

Bradford Assay: The Bradford method utilizes the binding of Coomassie Brilliant Blue G-250 dye to basic and aromatic amino acid residues (primarily arginine, tryptophan, tyrosine, histidine, and phenylalanine) [12] [10]. When the dye binds to protein, it undergoes a metachromatic shift from its cationic red form (λmax = 470 nm) to an anionic blue form (λmax = 595 nm). The amount of blue complex formed is proportional to protein concentration and measured spectrophotometrically. While rapid and simple, the Bradford assay shows significant protein-to-protein variation due to differential dye binding based on amino acid composition [12] [15].

Bicinchoninic Acid (BCA) Assay: The BCA method involves a two-step reaction where proteins first reduce Cu²⁺ to Cu⁺ under alkaline conditions (biuret reaction), followed by Cu⁺ complexation with BCA to form a purple-colored complex (λmax = 562 nm) [13] [10]. This assay responds primarily to the peptide backbone and certain side chains (cysteine, tyrosine, tryptophan), offering greater consistency across different proteins than the Bradford method. The BCA assay is temperature-dependent, with higher incubation temperatures increasing reactivity toward peptide bonds and reducing protein-to-protein variation [12].

Lowry Assay: The Lowry method combines the biuret reaction with the Folin-Ciocalteu reaction, where reduced copper-amide complexes further reduce phosphomolybdate-phosphotungstate reagents to produce a blue color (λmax = 750 nm) [12]. This assay detects tyrosine, tryptophan, cysteine, and peptide bonds, but has been largely superseded by the more robust BCA method due to interference issues and procedural complexity.

Fluorescence-Based Methods

Fluorescence assays provide non-specific quantification through the use of fluorescent dyes that interact with protein components. These methods include amine derivatization using dyes like o-phthalaldehyde (OPA) or fluorescamine, which react with primary amines (N-terminus and lysine side chains), and detergent-based probes like NanoOrange that exhibit enhanced fluorescence at protein-detergent interfaces [12]. Fluorescence methods typically offer improved sensitivity and broader dynamic range compared to colorimetric assays but may require specialized instrumentation and are susceptible to interference from fluorescent compounds [13].

Comparative Analysis of Method Performance

Understanding the relative strengths and limitations of specific versus non-specific protein quantification methods enables informed selection for particular applications. The following comparative analysis examines key performance characteristics across method categories.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Specific vs. Non-Specific Protein Quantification Methods

| Method | Principle | Specificity | Sensitivity | Dynamic Range | Key Interfering Substances |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A280 (Specific) | UV absorbance of aromatic amino acids [1] | Protein-specific (sequence-dependent) [14] | 0.1-1 mg/mL [10] | ~1.0-100 μg/mL (with dilution) [1] | Nucleic acids, detergents, phenols [10] |

| ELISA (Specific) | Antibody-antigen binding [10] | High (epitope-dependent) | pg/mL-ng/mL [10] | ~4-5 orders of magnitude [10] | Cross-reactive antigens |

| Bradford (Non-specific) | Coomassie dye binding to basic/aromatic residues [12] | Total protein (varies by composition) [15] | 1-20 μg/mL [10] | 1-1500 μg/mL [10] | Detergents (SDS, Triton), alkaline buffers [10] |

| BCA (Non-specific) | Copper reduction & BCA chelation [13] | Total protein (varies by composition) | 0.5-20 μg/mL [10] | 20-2000 μg/mL [10] | Reducing agents, metal chelators [10] |

| Lowry (Non-specific) | Copper reduction & Folin-Ciocalteu reaction [12] | Total protein (varies by composition) | 1-100 μg/mL | 5-500 μg/mL | Detergents, reducing agents, sugars [12] |

Table 2: Applicability and Practical Considerations for Protein Quantification Methods

| Method | Sample Volume | Time Required | Cost Considerations | Best Suited Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A280 | 1-50 μL (microvolume) [15] | <5 minutes [10] | Low (no reagents) [1] | Purified proteins, in-process monitoring [1] |

| ELISA | 50-100 μL | 2-6 hours [10] | High (antibodies, reagents) [10] | Complex mixtures, specific target quantification [10] |

| Bradford | 10-1000 μL | <10 minutes [10] | Low-moderate [15] | Quick estimates, non-denatured proteins [12] |

| BCA | 10-1000 μL | 45 minutes-1 hour [15] | Low-moderate [15] | Detergent-containing samples, general purpose [13] |

| Lowry | 100-1000 μL | 30-60 minutes | Low-moderate | Historical comparisons, research applications |

The data reveal fundamental trade-offs between specificity, sensitivity, and practical considerations. Specific methods like A280 and ELISA provide targeted quantification but may require purified samples or specialized reagents. Non-specific methods offer broader applicability for total protein measurement but exhibit variable responses across different proteins [12]. The Bradford assay, for instance, shows strong dependence on basic amino acid content, potentially underestimating concentrations for proteins with low arginine or lysine content [12]. Similarly, the BCA assay responds variably to different protein compositions, though high-temperature incubation can reduce this variability [12].

Experimental Protocols for Key Methods

A280 Specific Quantification Protocol

Principle: Direct UV absorbance measurement of aromatic amino acids (tryptophan, tyrosine) at 280 nm based on the Beer-Lambert law [1].

Materials and Reagents:

- UV-transparent cuvettes (quartz) or microvolume spectrophotometer

- Protein sample in appropriate buffer

- Reference buffer (matching sample buffer composition)

- Purified protein standard of known concentration (for verification)

Procedure:

- Equilibrate spectrophotometer and set detection wavelength to 280 nm.

- Blank the instrument using reference buffer.

- For fixed-pathlength measurements (typically 1 cm), ensure sample absorbance falls within the instrument's linear range (0.1-1.0 AU). For concentrated samples, dilute with reference buffer to achieve appropriate absorbance.

- For variable-pathlength systems (e.g., SoloVPE), the instrument automatically adjusts pathlength to maintain optimal absorbance [16].

- Measure sample absorbance at 280 nm.

- Calculate concentration using the Beer-Lambert law: c = A/(ε×l), where ε is the molar extinction coefficient and l is pathlength.

Critical Considerations:

- Ensure the protein contains tryptophan or tyrosine residues for accurate quantification.

- Correct for light scattering if necessary, particularly for turbid samples.

- Verify buffer compatibility; many common buffers (e.g., Tris, imidazole) absorb at 280 nm and may interfere [1].

- For variable-pathlength systems, slope spectroscopy (A/l = εc) eliminates dilution requirements and associated errors [16].

BCA Non-Specific Quantification Protocol

Principle: Two-step reaction involving copper reduction by proteins under alkaline conditions followed by color development with bicinchoninic acid [13] [10].

Materials and Reagents:

- BCA working reagent (50:1 ratio of BCA reagent to 4% CuSO₄)

- Protein standards (BSA typically 0-2000 μg/mL)

- Sample tubes or microplate

- Water bath or incubator (37°C or 60°C)

- Spectrophotometer or plate reader capable of reading 562 nm

Procedure:

- Prepare protein standards in the same buffer as unknown samples.

- Add aliquots of standards and unknowns to tubes or microplate wells.

- Add BCA working reagent (typically 1:8 sample:reagent ratio).

- Mix thoroughly and incubate at 37°C for 30 minutes or 60°C for 15 minutes.

- Cool samples to room temperature and measure absorbance at 562 nm.

- Generate standard curve and interpolate unknown concentrations.

Critical Considerations:

- Incubation temperature affects sensitivity and protein-to-protein variation.

- Compatible with detergents but interfered by reducing agents (DTT, β-mercaptoethanol) and metal chelators (EDTA) [13].

- For dilute samples, use the microplate format with enhanced incubation at 60°C for improved sensitivity [12].

Diagram 1: Method selection framework for protein quantification approaches.

Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

Successful protein quantification requires appropriate selection of reagents and materials tailored to the chosen method. The following table outlines essential solutions and their functions in protein quantification workflows.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Protein Quantification

| Reagent/Material | Function | Method Applicability | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quartz Cuvettes | Sample holder for UV measurements | A280 | UV-transparent; required for wavelengths <300 nm [1] |

| BCA Working Reagent | Color development through copper chelation | BCA | Fresh preparation recommended; composition affects sensitivity [13] |

| Coomassie Brilliant Blue G-250 | Protein-binding dye | Bradford | Distinct from R250 used in gel staining [15] |

| Protein Standards (BSA) | Calibration reference | All quantitative methods | Match protein type to unknowns when possible [13] |

| Microplate Readers | Absorbance/fluorescence measurement | BCA, Bradford, ELISA | Enable high-throughput analysis [13] |

| Variable Pathlength Systems | Automated pathlength adjustment | A280 | Eliminate dilution requirements; enhance accuracy [16] |

The distinction between specific and non-specific protein quantification methods represents a fundamental consideration in experimental design across biological research and biopharmaceutical development. Specific methods like A280 absorbance and ELISA provide targeted measurement of particular proteins, leveraging unique structural features or antibody recognition for selective quantification. These approaches are indispensable when the concentration of a specific protein, rather than total protein content, is physiologically or functionally relevant.

Non-specific methods including Bradford, BCA, and Lowry assays offer practical solutions for total protein quantification, responding to general protein characteristics like peptide bonds or particular amino acid side chains. While these methods provide valuable information about overall protein content, their variable response to different protein compositions necessitates careful interpretation and appropriate standard selection.

Method selection should be guided by the specific research question, sample characteristics, and required performance parameters. For purified protein analysis, A280 quantification offers rapid, non-destructive measurement with minimal sample consumption. In complex mixtures requiring target-specific measurement, immunoassays provide the necessary specificity despite greater complexity and cost. For general laboratory applications where total protein content is sufficient, colorimetric assays like BCA and Bradford balance practicality with adequate performance for most applications. Understanding the principles, capabilities, and limitations of each method enables researchers to select the optimal approach for their specific protein quantification needs.

The Critical Role of Aromatic Amino Acids and Protein Composition

The accurate determination of protein concentration is a fundamental requirement in biochemical, pharmaceutical, and biomedical research. However, the diverse physicochemical properties of proteins and the complexity of biological samples present significant analytical challenges. Protein quantification methods can be broadly categorized into specific techniques that rely on the unique aromatic amino acid composition of proteins and nonspecific techniques that measure general protein properties or reactions. Specific methods, such as UV absorbance at 280 nm (A280) and aromatic amino acid analysis (AAAA), exploit the characteristic UV absorption of tryptophan, tyrosine, and phenylalanine residues. These methods provide absolute quantification but require knowledge of the protein's aromatic amino acid composition. In contrast, nonspecific methods like colorimetric assays (Bradford, BCA) measure protein content through dye-binding or chemical reduction reactions, which are highly dependent on the amino acid composition of standard proteins used for calibration and are susceptible to interference from complex matrices [17] [18].

The composition of aromatic amino acids in a protein directly influences the selection and performance of quantification methods. Proteins with challenging properties, chemical modifications, or those in complex matrices like air particulate matter and pollen extracts further complicate accurate quantification [17]. This guide objectively compares the performance of specific and nonspecific protein quantification methods, providing experimental data and protocols to inform method selection for research and development applications.

Comparative Performance of Protein Quantification Methods

Quantitative Comparison of Method Performance

Table 1: Performance characteristics of different protein quantification methods

| Method | Principle | Detection Range | Precision & Recovery | Matrix Effects | Sample Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A280 (Direct UV) | Specific absorption of aromatic amino acids [17] | Varies with aromatic content; extended range with variable pathlength (0.005-15 mm) [16] | High accuracy when extinction coefficient is known; ~2% instrumental error [16] | Susceptible to interfering UV-absorbing compounds [17] | 10-300 μL (for variable pathlength) [16] |

| Aromatic Amino Acid Analysis (AAAA) | Quantification of Phe and Tyr after hydrolysis [17] [19] | Wide range after hydrolysis; LOD improved with fluorescence detection [17] | 97% recovery for Phe and Tyr; 98% ± 2% (Phe) and 88% ± 4% (Tyr) for BSA CRM [19] | Robust to complex matrices; hydrolysis required [17] | Requires hydrolysis (1h with 8M HBr at 150°C) [19] |

| Bradford Assay | Nonspecific dye binding to basic and aromatic residues [17] [20] | Limited linear range; superior to A280 but surpassed by TCE fluorescence [20] | Protein-dependent response; affected by Arg, Lys, His, Trp, Tyr, Phe content [17] | Highly susceptible to interference from detergents and chemicals [17] | Small volumes (2-5 μL typically used) [20] |

| BCA Assay | Nonspecific copper reduction by proteins [17] | Standard range | Protein-dependent response; affected by Cys, Cystine, Met, Tyr, Trp [17] | Susceptible to interfering reducing agents [17] | Standard volumes |

| TCE Fluorescence | Specific UV-induced modification of Trp and Tyr residues [20] | 10.5-200 μg (100μL assay); 8.7-100 μg (20μL assay) [20] | Superior sensitivity vs. A280; extends beyond Bradford linear range [20] | Specific to Trp/Tyr content; minimal chemical interference [20] | 10-100 μL; compatible with downstream SDS-PAGE [20] |

| qNMR of Aromatic AAs | Quantitative NMR of Phe and Tyr after hydrolysis [19] | Limited by NMR sensitivity | 97% recovery for His, Phe, Tyr at ~1 mM [19] | Minimal interference due to clean aromatic region [19] | Requires hydrolysis and specialized NMR equipment |

Advanced and Emerging Techniques

Table 2: Advanced methodologies for protein quantification

| Technique | Principle | Throughput & Applications | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Label-Free LC-MS | LC separation with MS detection of tryptic peptides [21] [22] | High-throughput; discovery proteomics [21] | No isotope labeling required; unlimited sample number [21] | Complex data analysis; requires advanced instrumentation [22] |

| LC-UV (220 nm) | Peptide bond absorption at 220 nm [17] | Medium-throughput; complex samples | Eliminates many interfering substances via separation [17] | Many substances absorb at 220 nm; protein-to-protein variability [17] |

| Raman Spectroscopy | Inelastic scattering providing molecular fingerprints [23] | Real-time bioprocess monitoring | Non-destructive; rich molecular information [23] | Cost and technical implementation hurdles [23] |

| Variable Pathlength UV | Slope spectroscopy using multiple pathlengths [16] | High-throughput biopharmaceutical processing | Eliminates dilution requirements; rapid results (minutes) [16] | Specialized equipment required |

Experimental Protocols for Key Methodologies

2,2,2-Trichloroethanol (TCE) Fluorescence Assay

The TCE fluorescence method represents a specific quantification technique that exploits the photochemical modification of aromatic amino acids. The protocol below enables highly sensitive protein quantification with visualization capabilities [20].

Reagents and Solutions:

- 2,2,2-trichloroethanol (TCE) stock solution: 0.56% (v/v) TCE in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for standard assay

- TCE Ultra Reagent: 5% (v/v) TCE in PBS for low-volume assay

- Protein standards: Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) in PBS (0-20 μg/μL)

- Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS): 137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 10 mM Na₂HPO₄, 1.8 mM KH₂PO₄

Standard Assay Protocol (100 μL):

- Combine 10 μL of protein sample with 90 μL of TCE reagent (0.56% v/v final concentration)

- Incubate mixture under a 15 W UV lamp for 15 minutes

- Measure fluorescence with excitation at 310 nm and emission at 450 nm

- Generate standard curve using BSA standards (0-20 μg/μL)

Low-Volume Assay Protocol (20 μL):

- Combine 10 μL of protein sample with 10 μL of TCE Ultra Reagent (5% v/v final concentration)

- Incubate under UV light for 0-15 minutes while monitoring fluorescence

- Measure fluorescence (excitation 310 nm, emission 450 nm)

- Use remaining sample for SDS-PAGE by dilution with 2X Laemmli Sample Buffer

Key Optimization Parameters:

- Optimal TCE concentration: 0.5% (v/v) final assay concentration

- Optimal UV-exposure time: 15 minutes

- Linear range: 10.5-200 μg (100 μL assay); 8.7-100 μg (20 μL assay)

- Post-assay visualization: Direct fluorescence visualization on UV transilluminator after SDS-PAGE

Aromatic Amino Acid Analysis (AAAA) with Fluorescence Detection

AAAA represents a gold-standard specific method that quantifies proteins based on their phenylalanine and tyrosine content after acid hydrolysis, providing robust quantification even for complex samples [17] [19].

Reagents and Equipment:

- Hydrolysis acid: 8 M hydrobromic acid (HBr) or 6 M hydrochloric acid (HCl)

- Reducing agent: Cysteine hydrochloride

- Internal standards: Terephthalic acid or sulfoisophthalic acid

- Mobile phase: Reversed-phase HPLC solvents

- HPLC system with fluorescence detection

Hydrolysis Protocol:

- Transfer protein sample to hydrolysis vial

- Add 8 M HBr containing 0.1% phenol as a protective agent

- Seal vial under vacuum or nitrogen atmosphere

- Heat at 150°C for 1 hour (HBr) or 6 M HCl at 107°C for 24 hours

- Cool and evaporate acid under vacuum

- Reconstitute hydrolysate in appropriate buffer for analysis

Liquid Chromatography with Fluorescence Detection:

- Column: Reversed-phase C18 column (e.g., 100 × 4.6 mm, 2.7 μm)

- Mobile phase A: 10 mM sodium phosphate, pH 7.0

- Mobile phase B: Methanol

- Gradient: 0-60% B over 5 minutes

- Fluorescence detection: Excitation 210 nm, Emission 305 nm

- Quantification: Peak areas of Phe and Tyr compared to internal standard

Quantification Calculations:

- Protein concentration = (moles Phe + moles Tyr) × MW protein / number of aromatic residues per protein

- Recovery: Typically 97% for standard amino acids; 98% ± 2% for Phe and 88% ± 4% for Tyr in BSA certified reference material

Variable Pathlength UV Spectroscopy (Slope Spectroscopy)

This advanced specific method enables accurate A280 measurements without sample dilution by leveraging variable pathlength technology, particularly valuable for concentrated biopharmaceutical products [16].

Instrumentation and Reagents:

- Solo VPE system or equivalent variable pathlength spectrophotometer

- Quartz sample cups (large, small, micro sizes)

- Protein sample without dilution

- Reference buffer matching sample composition

Protocol:

- Place sample in appropriate cup based on expected concentration

- Instrument automatically selects optimal pathlength range (0.005-15 mm)

- System collects 5-10 absorbance measurements at different pathlengths

- Software plots linear regression of absorbance versus pathlength

- Slope value (m) is used to calculate concentration: c = m/α, where α is molar absorption coefficient

Key Advantages:

- Eliminates dilution-related errors (~2% instrumental error only)

- Rapid analysis (<1 minute per sample)

- Handles concentrated samples (up to 300 mg/mL)

- No baseline correction required when buffer absorbance is pathlength-independent

Visualizing Protein Quantification Methodologies

Specific vs. Nonspecific Quantification Pathways

TCE Fluorescence Assay Workflow

Aromatic Amino Acid Analysis (AAAA) Workflow

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key reagents and materials for protein quantification experiments

| Reagent/Material | Function & Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| 2,2,2-Trichloroethanol (TCE) | Fluorescent labeling of tryptophan and tyrosine residues [20] | UV-induced covalent modification; enables sensitive detection (8.7-200 μg range) [20] |

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) | Standard reference protein for calibration curves [17] [20] | Widely available; consistent aromatic amino acid composition; used in AAAA validation [19] |

| Coomassie Blue G-250 | Dye for Bradford colorimetric assay [17] [20] | Binds basic (Arg, Lys) and aromatic amino acids; susceptible to detergent interference [17] |

| Bicinchoninic Acid (BCA) | Copper reduction detection in BCA assay [17] | Detects Cu+ ions produced by protein reduction; affected by Cys, Tyr, Trp content [17] |

| Hydrobromic Acid (HBr) | Protein hydrolysis for AAAA [19] | Enables rapid hydrolysis (1h at 150°C); preserves aromatic amino acids [19] |

| Deuterated Solvents | NMR analysis for qNMR quantification [19] | Enables quantitative NMR of aromatic amino acids after hydrolysis [19] |

| Internal Standards (e.g., terephthalic acid) | qNMR quantification reference [19] | Provides compound-independent calibration for absolute quantification [19] |

The selection between specific and nonspecific protein quantification methods represents a critical decision point in experimental design, with significant implications for data accuracy and reliability. Specific methods leveraging aromatic amino acid composition—particularly AAAA with fluorescence detection, TCE fluorescence, and advanced A280 with variable pathlength technology—provide superior accuracy and robustness for complex samples. These methods enable absolute quantification traceable to fundamental chemical properties, with AAAA demonstrating remarkable resilience to matrix effects in challenging environmental and biological samples [17].

Nonspecific methods including colorimetric assays offer practical convenience and sensitivity for controlled applications with known protein composition but demonstrate significant vulnerability to matrix interference and protein-to-protein variability. The experimental data presented in this comparison underscores the necessity of method matching to specific application requirements, with aromatic amino acid-based methods providing the foundation for reliable quantification in drug development and complex biomedical research.

For researchers navigating the critical role of aromatic amino acids and protein composition in quantification assays, the emerging methodologies of TCE fluorescence and variable pathlength spectroscopy present particularly valuable tools that balance sensitivity, specificity, and practical implementation for 21st-century protein science.

Accurate protein quantification is foundational to biomedical research and drug development. However, the choice between specific and non-specific ultraviolet-visible (UV-Vis) spectroscopy methods is critically influenced by common laboratory substances that can interfere with measurements, potentially compromising data reliability. This guide objectively compares the performance of various protein quantification assays in the presence of nucleic acids, detergents, and buffer components, providing a framework for selecting the optimal method.

Mechanisms of Interference in UV-Vis-Based Protein Assays

Protein quantification assays function on distinct chemical principles, making them differentially susceptible to interference. Understanding these mechanisms is the first step in mitigating analytical error.

Direct UV Absorbance at 280 nm: This method relies on the innate absorbance of aromatic amino acids (tryptophan and tyrosine) in the protein backbone [24] [25]. Its primary weakness is a lack of specificity; any substance that absorbs light around 280 nm will cause a positive interference, leading to overestimation of protein concentration. Key interferents include nucleic acids (which absorb strongly at 260 nm, with significant scatter into the 280 nm range) and specific buffer components like Tris-hydrochloride and reducing agents (e.g., DTT), whose oxidized forms also absorb at this wavelength [24] [25].

Colorimetric Assays (Bradford, BCA): These methods use a color change reaction that is subsequently measured by UV-Vis spectroscopy.

- The Bradford Assay depends on the binding of Coomassie dye primarily to basic (arginine) and aromatic residues in proteins [24]. The formation of this protein-dye complex can be disrupted by ionic and non-ionic detergents at certain concentrations, which may cause the dye to precipitate [24] [25]. The assay also exhibits significant protein-to-protein variation due to its dependence on amino acid composition.

- The Bicinchoninic Acid (BCA) Assay involves a two-step process: the reduction of Cu²⁺ to Cu⁺ by the protein backbone (biuret reaction), followed by the chelation of Cu⁺ by BCA to form a purple-colored complex [25]. While more tolerant of detergents than the Bradford assay, the BCA method is susceptible to interference from any substance that also reduces copper, including reducing agents like DTT and β-mercaptoethanol [25]. Chelating agents such as EDTA can also interfere by binding the copper ions required for the reaction.

The relationships between these core mechanisms and their primary interferents are visualized below.

Quantitative Comparison of Interference Effects

The following tables synthesize experimental data on the susceptibility of major protein quantification methods to specific interfering substances, providing a clear basis for comparison.

Table 1: Susceptibility of Protein Assays to Common Interferings Substances

| Interfering Substance | A280 (Direct UV) | Bradford Assay | BCA Assay | SLS-Hb (Hb-Specific) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nucleic Acids | High Interference (Absorb at ~260 nm) [24] [25] | Generally Compatible [24] | Generally Compatible [24] | Specific for hemoglobin, avoids interference [6] |

| Detergents | Varies by type and concentration | High Interference (e.g., SDS causes precipitation) [24] [25] | Low Interference (Tolerant of many detergents) [25] | Tolerant due to SLS detergent base [6] |

| Reducing Agents (DTT, BME) | High Interference (Oxidized forms absorb at 280 nm) [25] | Low Interference (Stable in reducing conditions) [25] | High Interference (Reduce Cu²⁺ independently) [25] | Not specifically reported |

| Chaotropic Salts | Can affect baseline absorbance | Can interfere with dye binding | Can interfere with copper reduction | Used in the method itself (enhances specificity) [6] |

| Chelators (EDTA) | Generally Compatible | Generally Compatible | High Interference (Chelates copper ions) [25] | Generally Compatible |

Table 2: Key Performance Characteristics of Quantification Methods

| Method | Chemical Basis | Key Advantage | Key Disadvantage | Optimal Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A280 (Direct UV) | Aromatic amino acids [25] | Quick; no special reagents [25] | Non-specific; many interferents [25] | Pure protein solutions, no contaminants |

| Bradford Assay | Shift upon binding basic/aromatic residues [24] [25] | Fast, stable, compatible with reducing agents [25] | Protein-to-protein variation; interfered by detergents [24] [25] | Quick screens of non-denatured proteins |

| BCA Assay | Cu²⁺ reduction by protein backbone [25] | Tolerant of detergents; more uniform protein response [25] | Slow; interfered by reducing agents and chelators [25] | Samples containing detergents |

| SLS-Hb | Hb-specific in SLS buffer [6] | High specificity for hemoglobin; safe and cost-effective [6] | Applicable only to hemoglobin-based samples [6] | Characterization of hemoglobin-based oxygen carriers (HBOCs) |

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Key Assays

To ensure reproducibility and highlight best practices for mitigating interference, detailed protocols for three core assays are provided below.

Bicinchoninic Acid (BCA) Assay Protocol

The BCA assay is known for its tolerance to detergents, making it suitable for many sample types, though it is sensitive to reducing agents [25].

- Standard Curve Preparation: Prepare a series of dilutions from a standard protein stock (e.g., Bovine Serum Albumin) in the same buffer as your unknown samples to create a concentration series covering 0–1.5 mg/mL [6].

- Sample Preparation: Dilute unknown protein samples to an estimated concentration that falls within the standard curve's range. Use triplicates for accuracy [6].

- Working Reagent Preparation: Combine BCA Reagent A and BCA Reagent B in a 50:1 ratio to create the BCA working reagent [6].

- Reaction:

- Absorbance Measurement: Using a plate reader, measure the absorbance of each well at 562 nm [6].

- Data Analysis: Generate a standard curve by plotting the average absorbance of the standards against their known concentrations. Use the linear equation from this curve to calculate the concentration of the unknown samples.

Bradford Assay Protocol

The Bradford assay is prized for its speed and compatibility with reducing agents, but is incompatible with many detergents [25].

- Standard Curve Preparation: Prepare standard protein dilutions (e.g., BSA or Bovine γ-Globulin) in a compatible buffer. A range of 0–1 mg/mL is typical [6].

- Sample Preparation: Dilute unknown samples appropriately. Use triplicates.

- Reagent Preparation: Allow the Coomassie Plus reagent to equilibrate to room temperature for at least 30 minutes before use [6].

- Reaction:

- Pipette 10 µL of each standard and unknown into a 96-well plate.

- Add 300 µL of Coomassie Plus reagent to each well.

- Cover the plate, mix, and incubate at room temperature for 10 minutes [6].

- Absorbance Measurement: Measure the absorbance at 595 nm using a plate reader [6].

- Data Analysis: Create a standard curve from the absorbance of the standards and calculate the unknown concentrations. Note that the standard curve may be non-linear at higher concentrations.

Direct UV Absorbance at 280 nm Protocol

This method is best reserved for purified protein samples where contaminating interferents are absent [25].

- Blank Measurement: Using a UV-Vis spectrophotometer, blank with the appropriate buffer solution that the protein is dissolved in. This is critical for accurate background subtraction [25].

- Spectrum Measurement:

- For microvolume systems (e.g., NanoDrop), place a 1-2 µL droplet of the purified protein sample on the pedestal and obtain a full UV-Vis spectrum, typically from 220 to 320 nm [26].

- For cuvette-based systems, load the sample into a quartz cuvette and measure.

- Concentration Calculation: The instrument software will typically calculate concentration based on the absorbance at 280 nm (A280), the pathlength, and the input extinction coefficient. The extinction coefficient is protein-specific and must be known beforehand [25]. A scan of the spectrum allows for assessment of purity; a pure protein sample typically shows a peak at ~280 nm, while nucleic acid contamination is indicated by a elevated peak at ~260 nm.

The workflow for selecting and executing an appropriate quantification assay, from sample preparation to data interpretation, is summarized below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Successful and reproducible protein quantification requires more than just a protocol. The following table details key reagents and materials, along with their critical functions and considerations.

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Protein Quantification

| Item | Function/Role in Quantification | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Standard Protein (BSA or BGG) | Creates a standard curve for colorimetric assays to interpolate unknown sample concentrations. | Protein-to-protein variation in colorimetric assays means the standard should be matched to the sample protein if possible [25]. |

| Coomassie Brilliant Blue G-250 | The active dye in the Bradford assay; binds proteins causing a spectral shift [24]. | Susceptible to precipitation in the presence of detergents; modified commercial kits offer better compatibility [24]. |

| Bicinchoninic Acid (BCA) & Cu²⁺ | The key reagents in the BCA assay. Cu²⁺ is reduced by proteins, and BCA chelates the resulting Cu⁺ [25]. | The assay is sensitive to chelators (e.g., EDTA) which bind Cu²⁺, and reducing agents which reduce Cu²⁺ independently [25]. |

| Sodium Lauryl Sulfate (SLS) | A detergent used in Hb-specific methods to create a uniform, stable complex for accurate spectrophotometric measurement [6]. | Its use in a dedicated kit enhances specificity and tolerability for hemoglobin-based samples [6]. |

| Chaotropic Salts (e.g., Guanidine HCl) | Disrupt cell structures, inactivate nucleases, and facilitate binding of nucleic acids to silica in purification kits [27]. | Essential for nucleic acid removal prior to A280 measurement to prevent interference [27]. |

| Microplate Reader | Instrument for high-throughput absorbance measurement in 96-well plate formats for BCA and Bradford assays [6]. | Enables rapid, multiplexed analysis of many samples and replicates, improving efficiency and statistical power. |

| UV-Vis Spectrophotometer | Instrument for measuring absorbance of samples at specific wavelengths (e.g., 280 nm, 562 nm, 595 nm) [28]. | Modern systems (e.g., NanoDrop) require only 1-2 µL of sample, conserving valuable material [26] [28]. |

In conclusion, the pervasive challenge of interference from nucleic acids, detergents, and buffers in protein quantification demands a strategic and informed approach. The data and protocols presented herein demonstrate that there is no universal "best" method, but rather an optimal choice dictated by sample composition and analytical requirements. For non-specific total protein analysis, the BCA assay offers robust performance in the presence of detergents, while the Bradford assay is preferable with reducing agents. For purified systems, direct A280 measurement provides a rapid solution. Crucially, in the development of complex biologics such as HBOCs, specific methods like SLS-Hb are indispensable for obtaining accurate and reliable quantitative data, ensuring both product efficacy and safety.

In both biomedical research and drug development, the accurate quantification of protein concentration is not merely a preliminary step but a foundational one. The reliability of virtually all subsequent data, from enzymatic studies to the validation of drug targets, hinges on the precision of this initial measurement [10]. The choice between specific and non-specific quantification methods carries profound implications for research accuracy, experimental reproducibility, and ultimately, the success or failure of therapeutic development programs [29].

This guide provides an objective comparison of mainstream protein quantification techniques, framing them within the context of this specific versus non-specific dichotomy. It synthesizes experimental data to illustrate how method selection influences outcomes in critical areas like the characterization of Hemoglobin-Based Oxygen Carriers (HBOCs) and the development of biopharmaceuticals, offering detailed protocols to support rigorous laboratory practice.

Classification of Protein Quantification Methods

Protein quantification methods can be fundamentally categorized based on what they measure. Non-specific methods determine total protein content by reacting with general chemical motifs, such as peptide bonds or specific amino acid side chains common to many proteins. In contrast, specific methods rely on unique, high-affinity interactions, such as antibody-antigen binding, to quantify a particular protein of interest within a complex mixture [29].

The diagram below illustrates the logical decision pathway for selecting an appropriate quantification method based on key experimental parameters.

Comparative Analysis of Key Protein Quantification Methods

Non-Specific Methods: Principles and Trade-offs

Non-specific methods are prized for their speed, low cost, and general applicability for measuring total protein content, but they are susceptible to interference from common buffer components [10] [25].

Ultraviolet-Visible (UV-Vis) Spectroscopy (Absorbance at 280 nm)

- Principle: This technique leverages the intrinsic absorbance of ultraviolet light (at 280 nm) by the aromatic amino acids tryptophan and tyrosine in a protein's sequence. The concentration is calculated using the Beer-Lambert law (A = εcl) [1] [30].

- Experimental Protocol:

- Blank the spectrophotometer with the protein's buffer solution.

- Measure the absorbance of the purified protein solution at 280 nm.

- Calculate concentration using the formula: c = A / (ε × l), where

cis concentration,Ais absorbance,εis the protein's molar extinction coefficient, andlis the path length of the cuvette [30].

Bicinchoninic Acid (BCA) Assay

- Principle: A two-step colorimetric reaction. First, proteins reduce Cu²⁺ to Cu⁺ under alkaline conditions (biuret reaction). Second, BCA chelates the Cu⁺ ions to form a purple complex with strong absorbance at 562 nm [10] [31].

- Experimental Protocol:

- Prepare a series of standard protein solutions (e.g., BSA) of known concentration.

- Mix the BCA working reagent (50 parts Reagent A with 1 part Reagent B) with standards and unknown samples in a microplate [29].

- Incubate at 37°C for 30 minutes [10] [29].

- Measure absorbance at 562 nm and determine sample concentration from the standard curve [10].

Bradford Assay

- Principle: This is a single-step assay where the Coomassie Brilliant Blue G-250 dye binds primarily to basic (arginine, lysine) and aromatic amino acids in proteins. This binding causes a shift in the dye's absorbance maximum from 470 nm (red) to 595 nm (blue) [10] [25].

- Experimental Protocol:

Specific Methods: The Power of Immunological Recognition

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

- Principle: ELISA uses the high specificity of antibodies to capture and detect a target protein. In a common "sandwich" format, a capture antibody is immobilized on a plate. The sample is added, and the target protein binds. A second, enzyme-conjugated detection antibody is then added. After adding a substrate, the resulting color change, proportional to the target protein concentration, is measured [10].

- Experimental Protocol:

- Coat a microplate with a capture antibody specific to the target protein and block to prevent non-specific binding.

- Add samples and standards, incubate, and wash.

- Add an enzyme-linked detection antibody, incubate, and wash.

- Add a substrate solution and measure the resulting absorbance. Concentration is determined from a standard curve [10].

The following table synthesizes experimental data from the literature, providing a direct comparison of the key performance characteristics of each method [10] [29] [31].

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Common Protein Quantification Assays

| Method | Principle | Dynamic Range | Sensitivity | Key Interfering Substances | Assay Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UV-Vis (A280) | Aromatic amino acid absorbance [1] | ~0.1 - 1 mg/mL (limited) [10] | Low (< 1 µg/mL problematic) [10] | Nucleic acids, detergents, phenols [10] [25] | ~5 minutes [10] |

| BCA Assay | Cu²⁺ reduction by protein/BCA chelation [10] | 20 - 2000 µg/mL [10] | Moderate (20 µg/mL) [10] | Reducing agents (DTT, β-Me), metal chelators (EDTA) [10] [31] | ~45 minutes [31] |

| Bradford Assay | Coomassie dye binding to basic/aromatic residues [10] | Varies with standard | Moderate | Detergents (SDS, Triton), alkaline buffers [10] [25] | < 10 minutes [10] |

| ELISA | Antibody-antigen specificity [10] | Varies with target | High (pg/mL range) [10] | Minimal due to antibody specificity [10] | Several hours [10] |

Table 2: Suitability for Different Sample Types and Workflows

| Method | Best For | Compatible With Detergents? | Sample Consumption | Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UV-Vis (A280) | Purified proteins, quick checks [1] | Low compatibility [10] | Very low (1-2 µL) [1] | Low (no reagents) [1] |

| BCA Assay | Samples with detergents, general lab use [10] [25] | Good compatibility [10] [25] | Moderate (25 µL in microplate) [29] | Low to Moderate [31] |

| Bradford Assay | Quick, high-throughput screens without detergents [10] | Poor compatibility [10] [25] | Low (10 µL in microplate) [29] | Low [31] |

| ELISA | Quantifying specific proteins in complex mixtures (serum, lysate) [10] | High compatibility [10] | Moderate | High (antibodies, reagents) [10] |

Case Study: Method Selection in Hemoglobin-Based Oxygen Carrier (HBOC) Development

The critical impact of method choice is powerfully illustrated in the development of HBOCs, where accurately measuring hemoglobin (Hb) content, encapsulation efficiency, and free Hb is essential for both efficacy and safety [29].

A 2024 comparative study evaluated UV-Vis-based methods for quantifying Hb extracted from bovine red blood cells. The research compared non-specific methods (BCA, Bradford, Abs280) with Hb-specific methods (Cyanmethemoglobin, SLS-Hb) [29].

- Key Experimental Findings:

- The study identified the SLS-Hb method as the preferred choice due to its specificity, ease of use, cost-effectiveness, and safety compared to cyanmethemoglobin-based methods [29].

- It highlighted a crucial pitfall: using a non-specific method like BCA or Bradford for HBOC characterization without confirming the absence of other proteins (e.g., from the RBC membrane) can lead to significant inaccuracies in calculating encapsulation efficiency and yield [29].

- An overestimation of free Hb could halt the development of a viable product, while an underestimation could allow a toxic product with high levels of free Hb to advance, posing serious clinical risks [29].

This case underscores the necessity of aligning the method's specificity with the scientific question, especially in a regulated development environment.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful protein quantification requires more than just a protocol. The following table lists key reagents and materials, along with their critical functions in ensuring accurate results.

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Protein Quantification

| Item | Function & Importance |

|---|---|

| Standard Protein (e.g., BSA, IgG) | Serves as the reference for generating a calibration curve. The choice of standard should closely match the composition of the sample protein for non-specific assays [10] [25]. |

| High-Purity Buffers & Water | Used for diluting standards and samples. Impurities can absorb light at critical wavelengths, leading to high background and inaccurate readings [1]. |

| Compatible Microplates & Cuvettes | Sample holders must be appropriate for the wavelength. Quartz is required for UV measurements, while specialized plastic is used for visible range assays [30]. |

| Detector-Compatible Reagents (BCA, Dye) | The core chemistries of the assays (e.g., BCA working reagent, Coomassie dye) must be formulated for use with standard laboratory spectrophotometers and plate readers [10] [29]. |

| Wash & Blocking Buffers (for ELISA) | Critical for removing unbound material and preventing non-specific antibody binding, which reduces background noise and improves assay sensitivity and specificity [10]. |

The selection of a protein quantification method is a consequential decision that directly impacts data integrity in drug development and research. No single method is universally superior; the optimal choice is dictated by the experimental context.

- For purified proteins of known sequence and extinction coefficient, UV-Vis at 280 nm offers a rapid, non-destructive option [1].

- For general total protein estimation in complex buffers, the BCA assay often provides a robust balance of compatibility and sensitivity [10] [25].

- For high-throughput screening where speed is critical and detergents are absent, the Bradford assay is highly efficient [10].

- For quantifying a specific protein within a complex biological matrix like serum or cell lysate, ELISA is the definitive choice due to its unparalleled specificity and sensitivity [10].

A growing trend in the field is the use of orthogonal methods—using two different quantification principles to validate results, particularly for critical applications like lot release of biologics [1]. Furthermore, emerging technologies like Microfluidic Diffusional Sizing (MDS) and RF biosensors offer promising, calibration-free alternatives for determining both concentration and affinity simultaneously, potentially overcoming key limitations of traditional assays [10] [11]. By understanding the principles, advantages, and limitations of each technique, scientists can make informed choices that enhance the accuracy, reproducibility, and success of their research and development efforts.

Methodologies in Practice: Protocols for BCA, Bradford, Direct UV, and Emerging Techniques

Accurate protein quantification is a cornerstone of biological research and biopharmaceutical development, forming the critical link between sample processing and data interpretation. Within the context of specific versus non-specific protein quantification methods, the Bicinchoninic Acid (BCA) Assay occupies a crucial position as a robust, colorimetric method that balances practical convenience with reliable performance across diverse sample types. Unlike specific methods like ELISA that target unique protein epitopes through antibody recognition, the BCA assay belongs to the category of non-specific methods that measure total protein content based on general chemical properties common to most proteins [32]. This non-specific approach provides distinct advantages for preliminary protein screening, total protein concentration assessment in complex mixtures, and situations where antibody development for specific detection would be impractical or cost-prohibitive.

The fundamental strength of the BCA assay lies in its unique chemical mechanism that leverages the reducing power of peptide bonds and specific amino acid residues, creating a detection system that is both sensitive and remarkably tolerant to substances that typically interfere with other colorimetric methods, particularly detergents commonly used in protein extraction and solubilization [12] [33]. This detergent compatibility makes the BCA assay indispensable for workflows involving membrane proteins, cellular lysates, and other challenging sample types where complete protein solubilization requires disruptive agents that would compromise other quantification methods.

Mechanistic Principles of the BCA Assay

The BCA assay operates through a two-step, temperature-dependent chemical reaction that converts protein presence into a measurable colorimetric signal. Understanding this mechanism is essential for appreciating both the strengths and limitations of this method compared to alternative protein quantification approaches.

The Biuret Reduction Step

In the initial reaction phase, proteins act as reducing agents in an alkaline environment (pH 11.25), facilitating the reduction of cupric ions (Cu²⁺) to cuprous ions (Cu⁺). This process, known as the biuret reaction, primarily occurs through the coordination of copper ions with peptide bonds that form coordination complexes under alkaline conditions [12] [34]. The reduction efficiency depends on two key factors: the number of peptide bonds present and the concentration of specific amino acid residues including cysteine, tyrosine, and tryptophan, which possess particularly strong reducing capabilities in alkaline environments [35] [25]. This dual pathway for copper reduction contributes to the method's broader protein-to-protein consistency compared to assays like Bradford, which relies heavily on specific amino acid interactions.

BCA Chelation and Color Development

The second stage involves the highly specific chelation of the newly reduced cuprous ions (Cu⁺) by two molecules of bicinchoninic acid (BCA), forming a stable, purple-colored complex [33] [35]. This BCA-Cu⁺ complex exhibits strong light absorption at 562 nm, with the intensity of this purple color being directly proportional to the protein concentration in the sample [34]. The reaction is not a true endpoint assay, as color development continues slowly over time, but reaches sufficient stability following incubation to allow reproducible measurement across multiple samples [35].

The following diagram illustrates the complete BCA assay mechanism:

Figure 1: BCA Assay Reaction Mechanism. The two-step process shows protein-mediated copper reduction followed by BCA-chelate formation resulting in measurable color development.

Experimental Protocol and Methodology

The BCA assay protocol follows a systematic approach to ensure accurate and reproducible protein quantification. The following section outlines the standard procedure adapted for microplate format, which enables high-throughput processing of multiple samples simultaneously [35].

Reagent and Standard Preparation

Working Reagent Preparation: The BCA working reagent is prepared immediately before use by combining Reagent A (containing sodium carbonate, sodium bicarbonate, bicinchoninic acid, and sodium tartrate in an alkaline medium) with Reagent B (containing copper sulfate) at a 50:1 ratio (50 mL Reagent A + 1 mL Reagent B) [35]. The mixed reagent is stable for approximately one week when stored properly.

Protein Standard Preparation: Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) serves as the reference protein for creating a standard curve. Prepare a dilution series covering the expected concentration range of unknown samples, typically from 25 μg/mL to 2000 μg/mL [35]. Precise standard preparation is critical for assay accuracy, as all unknown sample concentrations will be extrapolated from this standard curve.

Table 1: Example BSA Standard Preparation for Microplate BCA Assay

| Tube | Homogenization Buffer (μL) | BSA Stock (μL) | Final Concentration (μg/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | 0 | 100 stock | 2000 |

| B | 42 | 125 stock | 1500 |

| C | 110 | 110 stock | 1000 |

| D | 60 | 60 of B | 750 |

| E | 110 | 110 of C | 500 |

| F | 110 | 110 of E | 250 |

| G | 110 | 110 of F | 125 |

| H | 135 | 35 of G | 25 |

| I | 135 | 0 | 0 |

Sample Preparation and Assay Procedure

Sample Preparation: Unknown experimental samples typically require dilution (often 10-fold) in an appropriate buffer such as 1% homogenization buffer to fall within the detection range of the standard curve [35]. For tissues or cells, initial homogenization in detergent-containing buffer (e.g., 1% Triton X-100) followed by centrifugation is necessary to obtain clear supernatants for analysis.

Assay Procedure:

- Plate Setup: Transfer 25 μL of each standard and prepared unknown sample to appropriate wells of a 96-well microtiter plate, in duplicate or triplicate.

- Reagent Addition: Add 200 μL of pre-mixed BCA working reagent to each well containing standard or sample.

- Incubation: Cover the plate and incubate at 37°C for 30 minutes in the dark. The incubation time and temperature directly impact color development; consistent conditions are essential for reproducibility.

- Absorbance Measurement: Following incubation, check for and remove any bubbles that may interfere with reading. Measure the absorbance of each well at 562 nm using a plate reader [35].

Data Analysis and Calculation

Standard Curve Generation: Plot the average absorbance values for each BSA standard against their known concentrations. The relationship typically follows a near-linear pattern, particularly in the mid-range of concentrations, though a polynomial trend line may provide better fit across the entire range [35].

Concentration Calculation: Using the standard curve equation, calculate the protein concentration of unknown samples based on their measured absorbance values. Apply appropriate dilution factors to determine the original sample concentration, typically expressed as μg/μL or mg/mL.

The complete workflow is summarized below:

Figure 2: BCA Assay Workflow. The complete experimental procedure from reagent preparation to concentration calculation.

Compatibility with Detergents: Comparative Analysis

A defining characteristic of the BCA assay is its exceptional tolerance to detergents commonly used in protein extraction and solubilization, setting it apart from many other protein quantification methods. This compatibility makes it particularly valuable for research involving membrane proteins and cellular lysates where detergents are essential for protein solubility.

Mechanism of Detergent Tolerance

The BCA assay's detergent resistance stems from its two-step reaction mechanism. Unlike the Bradford assay, where detergents compete with the dye for binding sites on proteins, the BCA copper reduction reaction occurs effectively even in the presence of various detergents [32] [33]. The alkaline conditions of the assay (pH ~11.25) contribute to this tolerance by maintaining protein-detergeant complexes in solution without interfering with the copper reduction process. This compatibility extends to both ionic and non-ionic detergents, though at varying concentration thresholds.

Comparative Detergent Compatibility

When compared to alternative protein quantification methods, the BCA assay demonstrates superior performance in detergent-containing samples:

Table 2: Detergent Compatibility Across Protein Quantification Methods

| Method | Principle | Detergent Compatibility | Key Limitations with Detergents |

|---|---|---|---|

| BCA Assay | Copper reduction & BCA chelation | High tolerance to a wide range of detergents [33] | Sensitive to copper chelators (EDTA) and reducing agents |

| Bradford Assay | Coomassie dye binding to basic & aromatic residues | Low tolerance; detergents interfere with dye binding [32] [33] | Significant interference from ionic and non-ionic detergents |

| Lowry Assay | Copper reduction & Folin-Ciocalteu reaction | Moderate tolerance | Detergents can cause precipitate formation [12] |

| UV Absorbance (A280) | Aromatic amino acid absorption | Variable interference | Detergents may absorb at 280 nm, creating background interference |

| Fluorescence-Based | Fluorescent dye binding | Sensitive to detergents and high salt concentrations [12] | Quantum yield affected by detergent concentration |

This detergent compatibility is particularly crucial when working with transmembrane proteins, which require solubilization from lipid membranes for accurate quantification. Research has demonstrated that conventional methods like Bradford significantly underestimate membrane protein concentration due to limited dye accessibility to hydrophobic regions, whereas the BCA assay provides more reliable quantification in such challenging samples [32].

Comparative Performance with Alternative Methods

Understanding how the BCA assay performs relative to other protein quantification methods enables researchers to select the most appropriate technique for their specific application. The following comparative analysis highlights key performance metrics across multiple dimensions.

Quantitative Method Comparison

Direct comparison of protein quantification methods reveals distinct performance characteristics that guide method selection:

Table 3: Comprehensive Comparison of Protein Quantification Methods

| Assay Method | Detection Mechanism | Detection Range (μg/mL) | Sensitivity | Compatible with Detergents | Assay Time | Key Interfering Substances |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BCA | Copper reduction & BCA chelation | 20-2000 [34] | Moderate (25-2000 μg/mL) [33] | Yes [33] | ~30-120 min [33] [35] | Reducing agents, copper chelators (EDTA) [12] [34] |

| Bradford | Coomassie dye binding | 1-100 [25] | High (1-20 μg/mL) [33] | No [32] [33] | 5-10 min [33] | Detergents, alkaline conditions [32] [12] |

| Lowry | Copper reduction & Folin-Ciocalteu | 1-100 [12] | High | Moderate | ~30-60 min | Detergents, potassium ions, reducing agents [12] |

| UV A280 | Aromatic amino acid absorption | 100-1000 | Low | Variable | Immediate | Nucleic acids, alcohols, buffer ions [34] [25] |

| Qubit | Fluorescent dye binding | 0.25-5 | Very High | No [7] | ~10-15 min | Detergents, high salt [12] |

Application-Specific Performance

The optimal choice of protein quantification method depends heavily on the specific research context and sample characteristics:

Membrane Protein Studies: For transmembrane proteins like Na,K-ATPase (NKA), the BCA assay demonstrates superior performance compared to Bradford, Lowry, and direct UV methods. Research shows conventional methods significantly overestimate concentrations of specific transmembrane proteins compared to ELISA, with variation in resulting data being consistently lower when reactions are prepared based on BCA-determined concentrations [32].

Venom Proteomics: Studies on snake venoms from different species (Viperids vs. Elapids) reveal method-dependent variation in protein quantification. While multiple methods produced similar results for Viperid venoms (Agkistrodon contortrix), significant method-dependent variation was observed for Elapid venoms (Naja ashei), highlighting how protein composition affects quantification accuracy across methods [7].

High-Throughput Applications: The BCA assay adapts well to microplate formats, enabling processing of numerous samples simultaneously. Although requiring longer incubation times than Bradford assays, its broader dynamic range and detergent compatibility make it preferable for automated high-throughput applications, particularly when using robotic liquid handling systems [33].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of the BCA assay requires specific reagents and materials optimized for protein quantification. The following table outlines essential components and their functions within the assay system.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for BCA Assay

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| BCA Assay Kit | Complete reagent system for protein quantification | Typically contains BCA Reagent A and Copper Reagent B [35] |

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) | Protein standard for calibration curve | High purity, fatty acid-free recommended [35] |

| Microplate Reader | Absorbance measurement at 562 nm | Capable of reading 96-well or 384-well plates |

| Triton X-100 | Non-ionic detergent for membrane protein extraction | Used in homogenization buffers (typically 0.1-1%) [35] |