Specificity in Chromatographic Methods: A Comprehensive Guide for Robust Pharmaceutical Analysis

This article provides a thorough exploration of specificity testing for chromatographic methods, a critical parameter in pharmaceutical analysis and therapeutic drug monitoring.

Specificity in Chromatographic Methods: A Comprehensive Guide for Robust Pharmaceutical Analysis

Abstract

This article provides a thorough exploration of specificity testing for chromatographic methods, a critical parameter in pharmaceutical analysis and therapeutic drug monitoring. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it covers the foundational principles of specificity, including its definition and regulatory importance. The content details methodological approaches for achieving selective separations using modern LC-MS, HPLC-UV, and hyphenated techniques, alongside practical strategies for troubleshooting and optimizing methods to overcome interference from impurities, metabolites, and matrix components. Finally, it outlines the rigorous validation requirements per ICH, USP, and FDA guidelines, ensuring methods are fit-for-purpose in quality control and clinical applications, ultimately contributing to safer and more effective drug therapies.

The Critical Role of Specificity: Foundational Principles and Regulatory Imperatives

Defining Specificity and Selectivity in Chromatographic Separation

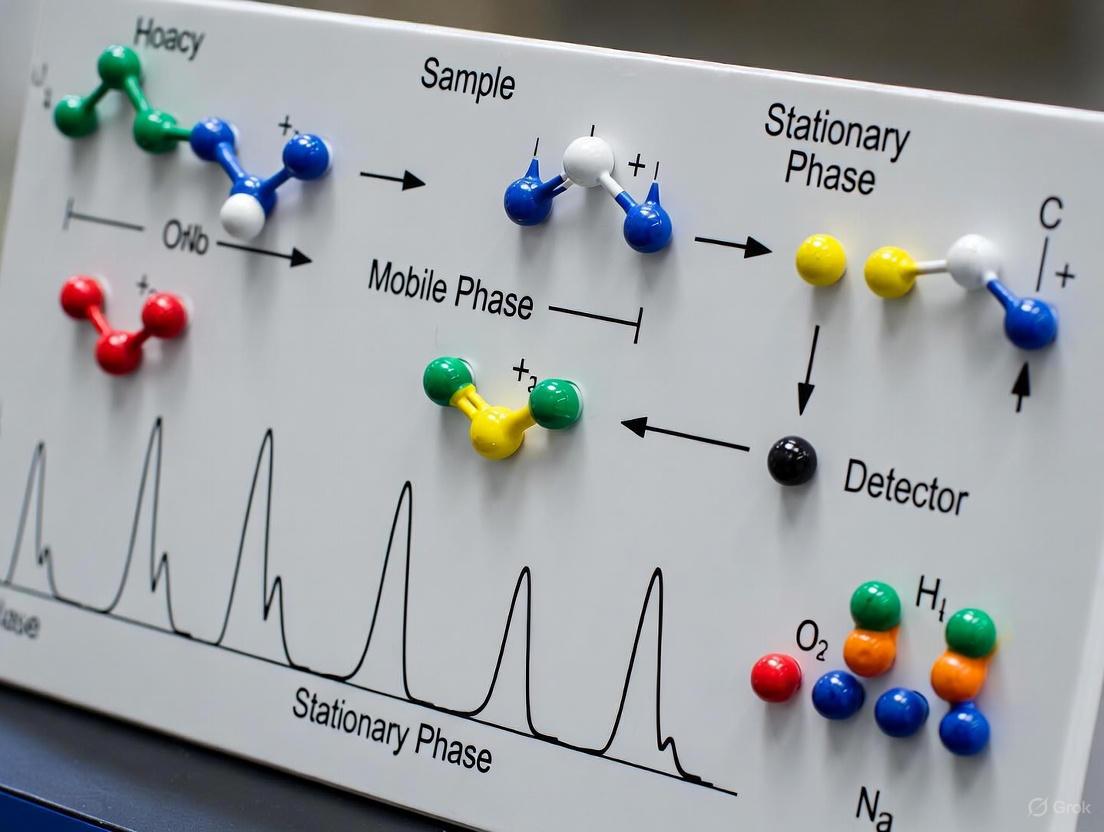

In the rigorous world of pharmaceutical analysis, the terms specificity and selectivity define the ability of a chromatographic method to accurately measure the analyte of interest in the presence of potential interferents. While sometimes used interchangeably, a crucial distinction exists: selectivity refers to the ability to distinguish and quantify multiple analytes in a mixture based on their differential migration rates, a consequence of their varying interactions with the stationary and mobile phases [1]. Specificity, often considered the ultimate degree of selectivity, is the ability to unequivocally assess the analyte in the presence of components such as impurities, degradants, or matrix elements that are expected to be present [2]. The fundamental principle underlying all chromatographic separation is the differential partitioning of compounds between a stationary phase and a mobile phase [1]. The extent of this partitioning, influenced by the physiochemical properties of the analyte, the stationary phase, and the mobile phase, determines the retention time and, ultimately, the success of the separation [1]. For drug development professionals, demonstrating method specificity is a critical regulatory requirement, ensuring that potency and purity assessments are reliable and that stability-indicating methods are truly stability-indicating.

Factors Governing Selectivity and Specificity

Achieving a selective separation is the first and most critical step in developing a specific method. This process is governed by a trio of interdependent factors.

- Stationary Phase Chemistry: The choice of stationary phase is the most powerful tool for manipulating selectivity. Interactions between the analyte and the stationary phase can include hydrophobic (dispersive) forces, dipole-dipole interactions, ionic bonding, and hydrogen bonding [3]. The trend in 2025 continues towards highly specialized phases. For small molecule reversed-phase liquid chromatography (RPLC), new columns featuring advanced particle bonding and inert hardware are enhancing peak shapes and providing alternative selectivity [4]. A significant development is the growth of biocompatible or bioinert columns with passivated hardware, which prevent the adsorption of metal-sensitive analytes like phosphorylated compounds, thereby improving analyte recovery and method specificity [4]. The introduction of phases like the phenyl-hexyl and biphenyl columns provides enhanced π–π interactions, which are particularly beneficial for separating structural isomers [4].

- Mobile Phase Composition: The mobile phase acts as a competing agent, eluting analytes from the stationary phase. In Reversed-Phase HPLC, changes in the organic solvent ratio (e.g., acetonitrile or methanol) directly impact retention and selectivity [1]. The use of gradient elution, where the mobile phase composition changes during the run, is essential for separating complex mixtures with components of widely varying polarity [1]. Additives such as acids, salts, or ion-pairing reagents can further fine-tune selectivity, particularly for ionizable compounds, by modifying their interaction with the stationary phase.

- Physical Parameters (Temperature and Flow Rate): Temperature influences the kinetics and thermodynamics of the separation process. Increasing the temperature typically reduces retention times and can improve peak shape by lowering mobile phase viscosity. In Gas Chromatography (GC), temperature control is even more critical, as elution order is primarily determined by boiling point, with secondary influences from stationary phase interactions such as Van der Waals forces, dipole-dipole interactions, and hydrogen bonding [5]. The flow rate of the mobile phase determines how long analytes are in contact with the stationary phase, affecting both the separation efficiency and the analysis time.

The relationship between these factors and the resulting chromatographic resolution is summarized in the workflow below.

Experimental Protocols for Demonstration

Protocol 1: Establishing Specificity via Forced Degradation

Forced degradation studies are a cornerstone of specificity validation for stability-indicating methods in pharmaceutical analysis.

- Objective: To demonstrate that the analytical method can accurately quantify the active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) and clearly separate it from its degradation products, even under stressed conditions.

- Materials: HPLC/UHPLC system with diode array detector (DAD); C18 column (e.g., 100 x 2.1 mm, 1.7 µm); reference standards of the API and known impurities; mobile phase components (e.g., water and acetonitrile, both with 0.1% formic acid).

- Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Expose the API solution to various stress conditions: acid hydrolysis (e.g., 0.1M HCl, 60°C, 1h), base hydrolysis (e.g., 0.1M NaOH, 60°C, 1h), oxidative stress (e.g., 3% H₂O₂, room temperature, 1h), and thermal stress (e.g., 80°C, 24h). Use a control sample of the unstressed API.

- Chromatographic Analysis: Inject the control and stressed samples. Employ a gradient elution, for example, from 5% to 95% acetonitrile over 10 minutes, with a flow rate of 0.4 mL/min. Column temperature should be maintained at 40°C. Detection is typically performed at 220-280 nm using a DAD.

- Data Analysis: Compare the chromatograms of the stressed samples to the control. The method is considered specific if the API peak is resolved from all degradation peaks (resolution, Rs > 1.5) and its purity is confirmed by the DAD (peak purity index > 0.999). The analyte recovery for the main peak in the presence of degradants should be 98-102%.

Protocol 2: Evaluating Selectivity for Isomeric Separations

This protocol uses GC-MRR, a highly specific technique, to separate and identify compounds that are challenging to resolve by conventional detectors.

- Objective: To achieve baseline separation and unambiguous identification of structural isomers and isotopologues in a complex mixture.

- Materials: Gas chromatograph coupled with a Molecular Rotational Resonance (MRR) spectrometer; capillary GC column (e.g., SLB-5ms, 30 m x 0.25 mm, 0.25 µm); standard mixtures of isomers (e.g., bromonitrobenzene or bromobutane isomers); high-purity helium or hydrogen carrier gas.

- Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare a standard mixture containing the target isomers in a suitable solvent (e.g., acetonitrile). The concentration should be appropriate for the detector's sensitivity.

- Chromatographic and Spectroscopic Analysis: Inject the sample (e.g., 1 µL) in split mode (e.g., 50:1). Use a temperature ramp (e.g., 40°C to 280°C at 10°C/min). The GC effluent is introduced into the MRR spectrometer, which uses a supersonic jet to cool analytes to ~2 K, simplifying their rotational spectra and enhancing signal strength [6].

- Data Analysis: The MRR detector measures the unique rotational transition frequencies of each molecule as it elutes from the GC. Because these frequencies are exquisitely sensitive to the three-dimensional mass distribution of the molecule, each isomer produces a distinct, fingerprint-like spectrum, allowing for unequivocal identification even of co-eluting compounds [6]. The signal is used to generate a highly specific chromatogram.

Comparative Performance Data

The following tables summarize quantitative data and key characteristics of different chromatographic approaches, highlighting their contributions to selectivity and specificity.

Table 1: Comparative Limits of Detection (LOD) for GC Detectors

| Analyte Class | GC-TCD | GC-MS | GC-MRR (with supersonic jet) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohols (e.g., Ethanol) | ~ nanograms | ~ picograms | ~ nanograms [6] |

| Halogenated Compounds | ~ nanograms | ~ picograms | ~ nanograms [6] |

| Nitrogen Heterocyclics (e.g., Pyridine) | ~ nanograms | ~ picograms | ~ nanograms [6] |

| Key Differentiator | Universal, less sensitive | Highly sensitive, can struggle with isomers | Unparalleled specificity for isomers/isotopologues [6] |

Table 2: Selectivity of Common HPLC Stationary Phases

| Stationary Phase | Primary Interactions | Ideal Application | 2025 Product Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| C18 | Hydrophobic | General purpose, non-polar to moderately polar small molecules | Raptor C8 (for faster analysis vs. C18) [4] |

| Phenyl-Hexyl | Hydrophobic, π-π | Separation of aromatic compounds, isomers | Halo 90 Å PCS Phenyl-Hexyl [4] |

| Biphenyl | Hydrophobic, π-π, dipole | Metabolomics, polar aromatics, isomers | Aurashell Biphenyl [4] |

| F5 (Pentafluorophenyl) | Dipole-dipole, π-π, hydrophobic | Complex mixtures with diverse functional groups | Raptor Inert HPLC Columns (with FluoroPhenyl) [4] |

| HILIC | Hydrophilic interaction, hydrogen bonding | Very polar, hydrophilic compounds | Raptor Inert HILIC-Si [4] |

Technological Advancements and Future Trends

The landscape of chromatographic separation is being reshaped by several key technological trends that are pushing the boundaries of selectivity and specificity.

- Artificial Intelligence and Automation: AI is increasingly used to automate method development. Machine learning algorithms can process large datasets to predict optimal chromatographic conditions (e.g., mobile phase composition, gradient profile, and column type), significantly reducing the time and resource investment required to achieve a selective separation [7] [8].

- Advanced Detection and Hyphenation: As demonstrated in the experimental protocol, coupling high-resolution separation with information-rich detectors is a powerful path to supreme specificity. Techniques like GC-MRR and LC-MS are at the forefront [6]. The market is also seeing growth in multi-dimensional chromatography (e.g., 2D-LC), which dramatically increases peak capacity and resolving power for incredibly complex samples like biologics and vaccines [1] [8].

- Miniaturization and Sustainability: There is a strong drive towards smaller, more efficient instrumentation. This includes using columns with smaller inner diameters and sub-2µm particles for UHPLC, which provide better resolution, higher sensitivity, and significantly reduced solvent consumption [7] [1]. This aligns with the principles of green analytical chemistry, a major trend in 2025 focused on reducing the environmental impact of laboratory operations [7] [8].

- Increased Inertness and Biocompatibility: The trend towards fully inert hardware is no longer a niche requirement but a standard expectation for methods involving metal-sensitive analytes, such as phosphorothioated oligonucleotides, certain APIs, and phosphorylated compounds in metabolomics. This hardware prevents analyte adsorption and degradation, ensuring accurate quantification and robust method performance [4].

The following diagram illustrates how these modern technologies are integrated into a workflow to achieve the highest level of analytical specificity.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Advanced Chromatography

| Item | Function | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| Halo Inert Column [4] | Reversed-phase column with passivated hardware to prevent metal-analyte interaction. | Critical for sensitive analysis of phosphorylated compounds, chelating PFAS, and metal-sensitive biomolecules. |

| Evosphere C18/AR Column [4] | RPLC column with monodisperse particles and C18/aromatic ligands. | Enables oligonucleotide separation without ion-pairing reagents, simplifying MS detection. |

| YMC Accura BioPro IEX Guard [4] | Bioinert guard cartridge made of polymethacrylate. | Protects analytical columns in IEX separations of biomolecules (proteins, antibodies, oligonucleotides); ensures high recovery. |

| Molecular Rotational Resonance (MRR) Spectrometer [6] | GC detector that measures unique rotational transitions for 3D structural fingerprinting. | Provides unparalleled specificity for identifying isomers, isotopologues, and co-eluting compounds without standards. |

| Supersonic Jet Expansion Module [6] | Cools GC effluents to ~2 K for MRR analysis. | Reduces rotational energy levels of molecules, dramatically enhancing MRR signal strength and sensitivity. |

In the realm of analytical chemistry, particularly for researchers and drug development professionals, the validity of experimental data is the cornerstone upon which safety and efficacy decisions are built. Among the various parameters of method validation, specificity stands apart as a fundamental, non-negotiable requirement. It is the quality that guarantees an analytical method is measuring the intended analyte, and nothing but the intended analyte, within a complex sample matrix. Without demonstrated specificity, claims regarding accuracy, precision, and reliability are fundamentally compromised. This guide explores the critical role of specificity by comparing chromatographic techniques and detailing the experimental protocols essential for its verification.

What is Specificity and Why is it Paramount?

In chromatographic analysis, specificity refers to the ability of the method to unequivocally separate and measure the target compound without interference from other components such as impurities, degradants, or the sample matrix itself [9]. Think of it as a highly trained detective who can accurately identify a single suspect in a crowded room.

Its non-negotiable status stems from three key areas:

- Ensures Analytical Accuracy: A highly specific method prevents overestimation or underestimation of the target analyte, providing confidence that the reported concentration reflects reality [9].

- Meets Stringent Regulatory Requirements: Regulatory bodies like the FDA mandate that methods used for quality control of pharmaceuticals and dietary supplements must be "accurate, precise, and specific for their intended purpose" [10]. A method lacking proven specificity will not meet Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) standards.

- Underpins Product Safety and Efficacy: In pharmaceuticals, an underspecific method might fail to detect a harmful degradant. In natural products chemistry, it could lead to incorrect quantification of active constituents, resulting in an under-potent or over-potent product [10].

Comparative Analysis of Chromatographic Techniques for Specificity

The choice of chromatographic column and hardware directly influences the specificity achievable for a given application. The following table summarizes recent innovations and their performance in addressing common specificity challenges.

Table 1: Comparison of Modern Chromatography Columns for Enhancing Specificity

| Column/Technology | Stationary Phase/Mode | Key Feature | Impact on Specificity & Analyte Suitability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Halo Inert [4] | Reversed-Phase (RPLC) | Inert (metal-free) hardware | Prevents adsorption; improves peak shape & recovery for phosphorylated & metal-sensitive compounds. |

| Raptor Inert HPLC [4] | RPLC (C18, Biphenyl, HILIC) | Inert hardware with SPPs | Improves chromatographic response for metal-sensitive polar compounds; reduces metal interaction. |

| Aurashell Biphenyl [4] | RPLC (Biphenyl) | π–π, dipole, steric mechanisms | Provides alternative selectivity; superior for separating isomers and hydrophilic aromatics. |

| Evosphere C18/AR [4] | Reversed-Phase | C18 & Aromatic ligands | Separates oligonucleotides without ion-pairing reagents; enhances specificity for complex biomolecules. |

| Ascentis Express BIOshell [4] | RPLC (C18) | Positively Charged Surface | Enhances peak shapes for basic compounds & peptides; offers alternative selectivity for complex mixtures. |

| Micropillar Array Columns [7] | Various | Lithographically engineered, uniform flow path | Enables high-precision, reproducible separation of thousands of samples (e.g., in multiomics). |

Essential Experimental Protocols for Demonstrating Specificity

Verifying specificity is a procedural exercise. The International Conference on Harmonisation (ICH) and FDA guidelines provide a framework, with the following protocols being central to demonstration.

Forced Degradation Studies

Forced degradation involves intentionally stressing a sample (e.g., with heat, light, acid, base, oxidant) to generate degradants. A specific method must be able to resolve the main analyte peak from all potential degradation products.

Detailed Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare a solution of the drug substance or product. Subject aliquots to various stress conditions: acidic (e.g., 0.1M HCl), basic (e.g., 0.1M NaOH), oxidative (e.g., 3% H₂O₂), thermal (e.g., 70°C), and photolytic (e.g., UV light). Use an unstressed sample as a control.

- Chromatographic Analysis: Inject the stressed samples and the control into the chromatographic system.

- Data Analysis: Examine the chromatogram for the appearance of new peaks (degradants). The method must demonstrate that the analyte peak is pure and resolved from all degradant peaks, typically with a resolution (Rs) value greater than 1.5. The mass balance (sum of all peaks) should be assessed to account for the degraded analyte.

Spike Recovery Experiments

This tests whether other components in the sample matrix interfere with the quantification of the analyte.

Detailed Protocol:

- Sample Preparation:

- Unspiked Sample: Analyze the actual sample to determine the initial concentration of the analyte.

- Spiked Sample: Add a known amount of a pure reference standard of the target analyte to the sample matrix. The spike level should be relevant to the expected concentration, often at 80%, 100%, and 120% of the label claim [10].

- Chromatographic Analysis: Analyze both the spiked and unspiked samples using the developed method.

- Data Analysis: Calculate the percentage recovery using the formula: Recovery (%) = [(Found in spiked sample - Found in unspiked sample) / Amount Added] × 100% A recovery value of 98-102% typically indicates the absence of significant matrix interference and demonstrates good method specificity and accuracy [10].

Analysis of Blank and Placebo Formulations

This simple but critical test confirms that the excipients in a drug product do not produce a signal that co-elutes with the analyte.

Detailed Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare a blank (the solvent only) and a placebo (a mixture of all excipients without the active ingredient).

- Chromatographic Analysis: Inject the blank, placebo, and the active sample.

- Data Analysis: The chromatogram at the retention time of the analyte in the blank and placebo should show no peaks (or a negligible peak compared to the active). This proves the signal is specific to the API.

Visualizing the Specificity Testing Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the logical sequence and decision points in a comprehensive specificity validation protocol.

Diagram 1: Specificity validation workflow.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

The following table details key reagents and materials crucial for conducting robust specificity experiments.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Specificity Testing

| Item | Function in Specificity Testing |

|---|---|

| High-Purity Reference Standard | Serves as the definitive benchmark for the target analyte's identity, retention time, and for creating the calibration curve. Purity must be verified [10]. |

| Placebo Formulation | A mixture of all inactive ingredients (excipients) used to confirm that no component co-elutes with or obscures the analyte peak. |

| Chromatography Column with Alternative Selectivity | A column with a different stationary phase (e.g., biphenyl, cyano) is used during method development to prove that separation from impurities is not accidental but robust. |

| Mass Spectrometry Detector | Provides definitive structural identification of the analyte and any potential interfering peaks, serving as the ultimate orthogonality test for specificity. |

| Inert HPLC Hardware | Columns and guards with passivated, metal-free fluid paths prevent analyte loss and peak tailing for metal-sensitive compounds, ensuring accurate quantification [4]. |

The Future of Specificity: AI and Advanced Materials

The pursuit of uncompromising specificity continues to drive innovation. The integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI) is beginning to automate method development and optimize system performance, potentially identifying optimal conditions for specific separations faster than traditional approaches [7]. Furthermore, the trend towards inert hardware is becoming standard for challenging analytes, ensuring that specificity is not undermined by surface interactions [7] [4]. As laboratories face increasing throughput demands, new column technologies like micropillar arrays and microfluidic chips promise to deliver high specificity and precision at an unprecedented scale [7].

In conclusion, specificity is the bedrock of reliable chromatographic analysis. It is not a mere box-ticking exercise but a rigorous, evidence-based demonstration that a method is fit for its purpose. By leveraging modern column technologies, adhering to robust experimental protocols, and embracing emerging tools like AI, scientists can ensure their methods possess the non-negotiable specificity required to advance drug development and ensure public safety.

In the pharmaceutical industry, the validation of analytical procedures is not just a best practice but a legal requirement for the regulated stability testing of drug substances (DS) and drug products (DP) [11]. The core objective of validation is to demonstrate that an analytical procedure is suitable for its intended purpose [11]. Among the various validation parameters, specificity is fundamental. It is defined as the ability of a method to assess unequivocally the analyte in the presence of components that may be expected to be present, such as impurities, degradation products, and matrix components [11]. For chromatographic methods, this translates to the physical separation of the active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) from other components like process impurities, degradants, or excipients [11]. Demonstrating specificity provides confidence that the analytical method is accurately measuring what it claims to measure, which is critical for ensuring drug quality, safety, and efficacy.

The regulatory landscape for specificity is shaped by major guidelines from the International Council for Harmonisation (ICH), the United States Pharmacopeia (USP), and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). In March 2024, the FDA issued the finalized "Q2(R2) Validation of Analytical Procedures" guidance, providing a general framework for the principles of analytical procedure validation [12]. This document, along with ICH Q2(R1) and USP general chapter <1225>, forms the cornerstone of regulatory expectations. Understanding the nuanced requirements and methodologies for demonstrating specificity is essential for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals to ensure regulatory compliance and the reliability of their analytical data.

Comparative Analysis of ICH, USP, and FDA Guidelines

The following table provides a structured comparison of the specificity requirements as outlined by the ICH, USP, and FDA. These guidelines are highly aligned but are applied in slightly different contexts.

Table 1: Key Regulatory Guidelines for Specificity in Chromatographic Methods

| Aspect | ICH Q2(R1) | USP General Chapter <1225> | FDA (as per Q2(R2)) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Definition | The ability to assess unequivocally the analyte in the presence of components that may be expected to be present. [11] | The ability of a method to measure the analyte accurately in the presence of interference. [11] | Provides a framework for validation principles, incorporating ICH Q2(R2). [12] |

| Primary Application | A harmonized guideline for drug registration applications in the EU, Japan, and the USA. [11] | Applies to compendial procedures used in testing articles for USP-NF. [11] | Required for analytical procedures used in quality assessments submitted to the agency. [11] [12] |

| Required Demonstration | Separation of the API from impurities and degradants. Use of forced degradation studies. [11] | Physical separation of the APIs from other components such as process impurities, degradants, or excipients. [11] | Relies on the principles outlined in ICH Q2(R2) for regulatory submissions. [12] |

| Typical Methodology | - Forced degradation studies.- Peak purity assessment (PDA/MS).- Comparison with a reference standard. [11] | - Analysis of placebo.- Forced degradation.- Use of an "orthogonal" procedure. [11] | - Science and risk-based approaches.- Phase-appropriate validation. [11] |

| Key Outputs | Chromatograms demonstrating resolution, peak purity data. [11] | Chromatograms demonstrating no interference from blank and placebo, and resolution from known impurities. [11] | Validation data included in regulatory filings (e.g., IND, NDA). [11] |

Experimental Protocols for Specificity Testing

A robust specificity study for a stability-indicating chromatographic method involves a multi-faceted experimental approach. The following workflow and detailed protocols outline the key steps.

Sample Preparation and Analysis

The foundation of specificity testing is the analysis of a comprehensive set of samples to rule out interference.

- Sample Set Preparation:

- Diluent/Blank: The solvent used to prepare the sample.

- Placebo: A mock drug product containing all excipients in the formulation without the API. For a drug substance, this may be a sample of process intermediates.

- Reference Standard: A highly characterized sample of the analyte(s) of known purity and concentration.

- Spiked Mixture ("Cocktail"): The API spiked with known impurities and degradation products available as reference materials. This solution is also valuable for system suitability testing (SST) [11].

- Chromatographic Analysis:

- All samples are analyzed using the proposed chromatographic method (e.g., reversed-phase HPLC with UV detection).

- The chromatograms are overlaid and examined for any interference at the retention times of the analyte peaks. The method is specific if the blank and placebo show no peaks co-eluting with the API or known impurities [11].

Forced Degradation Studies

Forced degradation (or stress testing) is critical for demonstrating that the method can separate degradation products from the main API.

- Protocol:

- Expose the drug substance or drug product to harsh conditions beyond those used for accelerated stability studies. Typical conditions include:

- Acidic and Basic Hydrolysis: Treatment with 0.1-1M HCl or NaOH at elevated temperatures (e.g., 40-80°C) for several hours or days.

- Oxidative Degradation: Treatment with hydrogen peroxide (e.g., 0.1-3%) at room or elevated temperature.

- Thermal Degradation: Solid and/or solution state exposure to high temperatures (e.g., 70-105°C).

- Photolytic Degradation: Exposure to UV and/or visible light as per ICH Q1B guidelines.

- The goal is to achieve approximately 5-20% degradation of the main compound to generate meaningful levels of degradants [11].

- Expose the drug substance or drug product to harsh conditions beyond those used for accelerated stability studies. Typical conditions include:

- Data Analysis:

- Analyze the stressed samples and demonstrate that the analyte peak is free from co-eluting peaks. This is initially assessed by the resolution between the API peak and the nearest degradant peak.

- The method should be able to detect the degradants formed above the reporting threshold [11].

Peak Purity Assessment

Peak purity evaluation is a powerful technique to confirm that an analyte chromatographic peak is attributable to a single component, even if it is not fully resolved from other peaks.

- Methodology:

- Utilize a Photo-Diode Array (PDA) Detector or Mass Spectrometry (MS).

- The PDA detector collects UV spectra across the entire chromatographic peak (at the peak apex, up-slope, and down-slope).

- Procedure:

- During the analysis of stressed samples and the spiked mixture, the PDA software compares the UV spectra at different points of the peak.

- A peak purity index is calculated. A value above a threshold (typically >990 or 995) indicates a spectrally pure peak, suggesting no co-elution [11].

- MS detection provides even more definitive proof by confirming a single mass ion for the eluting peak.

Orthogonal Method Verification

In complex cases, or to provide additional confirmation, specificity can be verified using a secondary, orthogonal method with a different separation mechanism.

- Protocol:

- Analyze key samples (e.g., the forced degradation sample) using a second, validated chromatographic method.

- This second method should have a different selectivity. For example, if the primary method is Reversed-Phase HPLC (RPLC), an orthogonal method could be a different RPLC method with a different column chemistry (e.g., HILIC, Ion-Pairing Chromatography, or a different pH) [11].

- Evaluation:

- The results from the orthogonal method should confirm the impurity profile and potency results obtained from the primary method, providing strong evidence for the method's specificity [11].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

The following table details key materials required for conducting comprehensive specificity tests for chromatographic methods.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Specificity Testing

| Item | Function / Purpose |

|---|---|

| High-Purity Reference Standard (API) | Serves as the benchmark for identifying the analyte's retention time and for assessing accuracy and linearity. Essential for peak identification [11]. |

| Authentic Impurity and Degradant Standards | Used to prepare spiked "cocktail" solutions to confirm the method can resolve the API from all known related substances. Critical for determining Relative Response Factors (RRF) [11]. |

| Placebo Formulation | A mixture of all non-active ingredients (excipients) in the drug product. Used to demonstrate that excipient peaks do not interfere with the analyte or impurity peaks [11]. |

| Photo-Diode Array (PDA) Detector | An advanced UV detector that collects full spectra across a peak. It is the primary tool for confirming peak purity and detecting potential co-elution [11]. |

| Mass Spectrometry (MS) Detector | Used for hyphenated techniques (e.g., LC-MS) to provide definitive identification of unknown peaks and confirm the molecular weight of analytes and degradants [11]. |

| Chromatography Data System (CDS) Software | Specialized software for controlling the HPLC system, acquiring data, and performing calculations for peak purity, resolution, and system suitability [11]. |

Case Study & Experimental Data Comparison

To illustrate the practical application of these protocols, consider a case study for validating a stability-indicating HPLC method for a small-molecule drug product. The following table summarizes hypothetical, but typical, experimental data generated from a specificity study.

Table 3: Sample Specificity Test Results for a Drug Product HPLC Method

| Sample | Retention Time of API (min) | Resolution from Nearest Peak | Peak Purity Index (PDA) | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diluent Blank | N/A | N/A | N/A | Pass: No peaks observed at the retention time of the API or known impurities. |

| Placebo | N/A | N/A | N/A | Pass: No interfering peaks from excipients. |

| API Reference Standard | 10.2 | N/A | 999.5 | Pass: Peak is spectrally pure. |

| API + Impurities Cocktail | 10.2 | > 2.0 from all impurities | 999.1 | Pass: All components are baseline resolved; API peak is pure. |

| Acid-Stressed Sample | 10.2 | 1.9 from Degradant A | 998.8 | Pass/Conditional Pass. Resolution is slightly below 2.0 but peak purity confirms no co-elution. May require method optimization. |

| Oxidized Sample | 10.2 | > 2.5 from all degradants | 999.3 | Pass: Well-separated degradants and pure API peak. |

Interpretation of Results: The data in Table 3 demonstrates that the method is specific for the analysis of the API. The absence of interference from the blank and placebo, combined with the baseline resolution from known impurities and the high peak purity indices in the forced degradation samples, provides strong evidence that the method is stability-indicating. The one resolution value of 1.9 might be flagged for monitoring during method maintenance but is considered acceptable when supported by a passing peak purity result.

In chromatographic analysis, achieving accurate quantification is fundamentally challenged by interference from metabolites, impurities, and the sample matrix. These factors can cause significant signal suppression or enhancement, leading to the misrepresentation of data, particularly in complex biological samples. Understanding and mitigating these effects through appropriate choice of chromatographic techniques and methodological adjustments is crucial for reliable results in drug development and metabolomics.

The following table summarizes the core interference challenges and the comparative performance of Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) and Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS) in addressing them.

| Challenge | Impact on Analysis | GC-MS Performance | LC-MS Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Matrix Effects | Co-eluting compounds cause ion suppression/enhancement, affecting accuracy and precision [13]. | Observed signal suppression/enhancement; for example, amino acids can be significantly affected, with effects reduced at higher concentrations or with optimized liner geometry [14]. | A major concern; caused by compounds co-eluting with the analyte interfering with the ionization process [13]. |

| Metabolite Interference | Similar chemical properties and incomplete separation lead to misidentification and inaccurate quantification [14]. | Matrix effects for carbohydrates and organic acids typically do not exceed a factor of ~2 in signal change [14]. | Can be addressed by optimizing chromatographic separation to prevent analyte co-elution with interfering metabolites [13]. |

| Endogenous Impurities (e.g., HbF) | Interferes with the accurate measurement of target analytes like HbA1c, leading to clinically significant deviations [15]. | HPLC-based methods demonstrated resilience, with no clinically significant deviation even at high (35%) HbF levels [15]. | Immunoassay and enzymatic methods showed clinically significant deviation at HbF levels above 10% [15]. |

| Co-eluting Impurities | Prevents baseline separation, essential for accurate quantification of individual compounds in a mixture [14] [16]. | Complex samples often show similar retention or incomplete separation of compounds [14]. | Modifying chromatographic conditions (e.g., mobile phase, column) can avoid co-elution, though this can be time-consuming [13]. |

Experimental Protocols for Investigating Interference

Protocol for Assessing Matrix Effects in GC-MS Profiling

This protocol, derived from a study on metabolite profiling, outlines a method to evaluate sample-dependent matrix effects [14].

- Objective: To systematically study the complex interactions and matrix effects between common constituents of biological samples during GC-MS analysis.

- Sample Preparation: Model compound mixtures of different compositions are used to simulate the complexity of biological samples. These mixtures contain representatives from various chemical classes (e.g., sugars, organic acids, amino acids) at concentrations differing by several orders of magnitude. A frequently applied derivatization protocol, such as trimethylsilylation, is then subjected to the samples [14].

- Chromatographic Analysis:

- Technique: Gas Chromatography coupled to Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS).

- Key Variable: The study investigates the impact of injection-liner geometry on the observed matrix effects [14].

- Data Analysis: Matrix effects are quantified as the factor of signal suppression or enhancement for target compounds (e.g., carbohydrates, organic acids, amino acids) when analyzed in a mixture versus in a pure form. The recovery of target compounds at different concentration levels within the dynamic range is assessed [14].

Protocol for Detecting and Correcting Matrix Effects in Quantitative LC-MS

This protocol provides a framework for a simple recovery-based method to detect and correct for matrix effects in LC-MS, as demonstrated in an assay for creatinine in urine [13].

- Objective: To detect and compensate for matrix effects in routine quantitative LC-MS analysis without requiring complex procedures or stable isotope-labeled internal standards.

- Sample Preparation: The sample matrix (e.g., human urine) is prepared, often by filtration or a simple clean-up step. For the standard addition method, the sample is divided into several aliquots, and the target analyte is spiked at different concentration levels into these aliquots [13].

- Chromatographic Analysis:

- Technique: Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS).

- Column: A Cogent Diamond-Hydride column (150 mm × 2.1 mm, 4-μm) [13].

- Mobile Phase: A gradient elution with mobile phase A (deionized water with 0.1% formic acid) and mobile phase B (acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid) [13].

- MS Detection: Multiple Reaction Monitoring (MRM) mode on a triple quadrupole mass spectrometer is used for specific and sensitive detection [13].

- Data Analysis:

- Matrix Effect Detection: The recovery of the analyte is calculated. A deviation from 100% recovery indicates the presence of matrix effects [13].

- Correction via Standard Addition: The signal response from the spiked aliquots is used to construct a standard addition curve. The absolute value of the x-intercept of this curve gives the original concentration of the analyte in the unspiked sample, effectively correcting for the matrix effect [13].

- Correction via Co-eluting Internal Standard: A structural analogue of the analyte that co-elutes with it is used as an internal standard. Its similar behavior allows it to experience the same matrix effects, enabling a correction [13].

Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists key reagents and materials essential for conducting the described experiments and mitigating interference challenges.

| Item Name | Function/Application | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Internal Standards (SIL-IS) | The most well-recognized technique to correct for matrix effects; co-elutes with the analyte and has nearly identical chemical properties [13]. | Considered the gold-standard method for rectifying matrix effects in quantitative LC-MS and GC-MS bioanalysis [13]. |

| Structural Analogue Internal Standard | A co-eluting compound with a structure similar to the analyte; a less expensive alternative to SIL-IS for correcting matrix effects [13]. | Used as an internal standard in LC-MS when SIL-IS are commercially unavailable or too expensive [13]. |

| Trimethylsilylation Derivatization Reagents | A chemical derivatization protocol used to make metabolites volatile and thermally stable for GC-MS analysis [14]. | Frequently applied in GC-MS metabolite profiling of complex biological samples [14]. |

| Chiral Stationary Phases | A chromatographic material designed to separate enantiomers, which often exhibit heterogeneous adsorption sites [16]. | Used in HPLC for separating chiral compounds, such as drugs; understanding their surface heterogeneity is key to optimizing separations [16]. |

| C18 Chromatography Column | A common reversed-phase stationary phase for separating non-polar to moderately polar compounds [13]. | Used in LC-MS method development; its surface heterogeneity can influence peak shape and contribute to matrix effects [16] [13]. |

| Formic Acid (Mobile Phase Additive) | An additive in the LC mobile phase to improve ionization efficiency and chromatographic peak shape [13]. | Used in the described LC-MS creatinine assay to facilitate protonation of the analyte in positive ion mode [13]. |

Strategic Workflows for Mitigation

The following diagrams illustrate the logical workflows for the two main experimental strategies discussed for tackling interference.

Diagram 1: Workflow for GC-MS Matrix Effect Investigation. This chart outlines the process of using model mixtures and derivatization to study and mitigate interference in GC-MS.

Diagram 2: Workflow for LC-MS Matrix Effect Correction. This chart shows the standard addition method used to detect and correct for ionization interference in LC-MS analysis.

The Fundamental Link Between Specificity, Patient Safety, and Drug Efficacy

In the field of drug development, the specificity of analytical methods forms the fundamental bridge between product quality, patient safety, and therapeutic efficacy. For biopharmaceuticals—complex molecules including recombinant proteins, monoclonal antibodies (mAbs), and cell-based therapies—this relationship is particularly crucial [17]. These products are characterized by high molecular weight, complex structures, and inherent heterogeneity, making them susceptible to variations that can impact safety and efficacy [17]. Unlike small-molecule drugs, biopharmaceuticals require sophisticated analytical techniques for comprehensive characterization due to their susceptibility to degradation and immunogenic responses [17].

Chromatographic methods serve as indispensable tools for ensuring the structural and functional integrity of these therapeutic agents. The global biopharmaceutical market, valued at approximately USD 452 billion in 2024 and projected to reach USD 484 billion by 2025, underscores the economic and therapeutic importance of these products [17]. As patents for originator biologics expire, the growing biosimilars market further emphasizes the need for robust analytical frameworks to demonstrate similarity in safety, purity, and potency without clinically meaningful differences [17]. This review objectively compares the performance of key chromatographic techniques in specificity testing, providing experimental data and methodologies essential for researchers and drug development professionals.

Comparative Analysis of Chromatographic Techniques

The selection of appropriate chromatographic techniques is paramount for addressing specific analytical challenges throughout the biopharmaceutical development lifecycle. Each method offers distinct advantages and limitations for characterizing therapeutic proteins, nucleic acids, and complex formulations.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Major Chromatographic Techniques in Biopharmaceutical Analysis

| Technique | Analytical Specificity | Throughput | Sensitivity | Quantitative Capability | Primary Applications in Biopharmaceuticals |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HPLC/UHPLC | High | Medium-High | Moderate-High | Excellent | Purity analysis, potency testing, stability indicating methods [18] [19] |

| LC-MS | Very High | Medium | High | Excellent | Structural elucidation, metabolite identification, biomarker discovery [20] [19] |

| HPTLC | Medium | High | Moderate | Good (with densitometry) | Herbal drug fingerprinting, purity assessment, reaction monitoring [18] [21] |

| GC-MS | High | Low-Medium | High | Excellent | Analysis of volatile compounds, residual solvents [19] |

| 2D-LC | Very High | Low | High | Excellent | Complex mixture analysis, biosimilar characterization [19] |

Table 2: Applicability of Techniques to Different Biopharmaceutical Product Types

| Product Type | Recommended Primary Techniques | Orthogonal Techniques | Key Analytical Targets |

|---|---|---|---|

| Monoclonal Antibodies | HPLC, LC-MS, CE-SDS | HIC, SEC, IEX | Aggregation, glycosylation, charge variants [17] |

| Gene Therapies | LC-MS, IEC, SEC | PCR, CE | Capsid content, impurity profiling, vector integrity |

| Herbal Formulations | HPTLC, HPLC | LC-MS, NMR | Authentication, adulteration detection, biomarker quantification [22] [18] |

| Recombinant Proteins | RP-HPLC, LC-MS, SEC | CD, IEX | Purity, molecular weight, post-translational modifications [17] |

| Biosimilars | 2D-LC, LC-MS, CE | BLI, SPR | Comprehensive similarity assessment [17] |

Advanced Chromatographic Methodologies and Applications

High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) and Ultra-HPLC

HPLC and UHPLC remain cornerstone techniques for biopharmaceutical analysis due to their robust quantitative capabilities and versatility. Recent innovations in column chemistry have significantly enhanced performance for specific applications. The 2025 market has seen introductions of columns with improved pH stability (operational range from pH 1-12), enhanced peak shapes for basic compounds, and specialized phases for challenging separations [4]. The Halo 90 Å PCS Phenyl-Hexyl column, for instance, provides alternative selectivity to C18 phases with enhanced peak shape and loading capacity for basic compounds, while the Halo 120 Å Elevate C18 column offers exceptional high pH- and high-temperature stability [4].

A critical trend involves the adoption of inert hardware to prevent adsorption of metal-sensitive analytes like phosphorylated compounds and certain peptides [4]. Technologies such as the Halo Inert column create a metal-free barrier between the sample and stainless-steel components, enhancing peak shape and improving analyte recovery [4]. These advancements directly impact patient safety by enabling more accurate quantification of potentially immunogenic impurities and aggregates.

Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS)

LC-MS has emerged as a transformative technology in biopharmaceutical analysis, combining superior separation capabilities with powerful structural elucidation [20] [19]. The integration of novel ultra-high-pressure techniques with highly efficient columns has enhanced the study of complex and less abundant bio-transformed metabolites [20]. LC-MS facilitates the investigation of complex biological systems, aiding in the identification of disease mechanisms and the rapid discovery of new therapeutic agents [20].

Key advancements in LC-MS instrumentation include the development of more efficient ionization sources (ESI, APCI, APPI), high-resolution mass analyzers (Orbitrap, Q-TOF, IT-Orbitrap), and improved ion optics that enable detection at picogram and femtogram levels [20] [19]. These developments are particularly valuable for biosimilar characterization, where demonstrating analytical similarity to reference products requires exceptional method specificity and sensitivity [17]. LC-MS-based multi-attribute methods (MAMs) provide comprehensive monitoring of critical quality attributes (CQAs) such as post-translational modifications, oxidation, deamidation, and glycosylation patterns that directly impact drug efficacy and immunogenicity [17].

High-Performance Thin-Layer Chromatography (HPTLC)

Despite the prominence of HPLC and LC-MS, HPTLC maintains relevance in specific applications, particularly herbal medicine analysis [18] [21]. Modern HPTLC systems offer automation, reproducibility, and accurate quantification through computer-controlled instrumentation and automation based on the full capabilities of conventional TLC [21]. Advanced systems like the CAMAG HP-TLC Visualisation Analyser incorporate high-resolution cameras, multi-spectral detection (UV, visible, fluorescence), and sophisticated software for quantitative evaluations and digital fingerprinting of complex samples [18].

HPTLC's strength lies in its ability to provide rapid chemical fingerprinting for authentication and quality control of herbal formulations, which is crucial given the complex mixtures of bioactive compounds in these products [22] [18]. The technique allows simultaneous analysis of multiple samples on the same plate, uses minimal solvent volumes, and enables detection of compounds that require post-chromatographic derivatization [18]. When coupled with techniques such as ultraviolet–visible spectroscopy, Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy, Raman spectroscopy, or mass spectrometry, HPTLC becomes a powerful tool for identification and structural elucidation [21].

Experimental Protocols for Specificity Testing

Protocol 1: HPLC Method for Monoclonal Antibody Charge Variant Analysis

Objective: To separate and quantify charge variants of a therapeutic monoclonal antibody using ion-exchange chromatography (IEX).

Materials:

- IEX Column: YMC-BioPro IEX, 5 μm, 4.6 × 250 mm [4]

- Mobile Phase A: 20 mM Sodium phosphate, pH 6.8

- Mobile Phase B: 20 mM Sodium phosphate, 500 mM NaCl, pH 6.8

- Detection: UV at 280 nm

- Sample Preparation: Dilute mAb sample to 1 mg/mL in Mobile Phase A

Chromatographic Conditions:

- Flow Rate: 0.8 mL/min

- Injection Volume: 10 μL

- Column Temperature: 25°C

- Gradient: 0-100% B over 30 minutes

Specificity Assessment: The method should resolve basic, main, and acidic variants. System suitability criteria include resolution ≥1.5 between basic and main peaks, and RSD ≤2.0% for main peak retention time across six injections.

Protocol 2: LC-MS Method for Peptide Mapping and Post-Translational Modification Analysis

Objective: To identify and characterize primary structure and post-translational modifications of a therapeutic protein.

Materials:

- Column: Ascentis Express C18, 2.7 μm, 2.1 × 150 mm [4]

- Mobile Phase A: 0.1% Formic acid in water

- Mobile Phase B: 0.1% Formic acid in acetonitrile

- Enzyme: Trypsin (sequencing grade)

- Mass Spectrometer: Q-TOF or Orbitrap system

Sample Preparation:

- Denature protein in 6 M guanidine hydrochloride, 50 mM Tris, pH 8.0

- Reduce with 5 mM dithiothreitol at 56°C for 30 minutes

- Alkylate with 15 mM iodoacetamide at room temperature for 30 minutes in the dark

- Desalt using size-exclusion chromatography or dialysis

- Digest with trypsin (1:20 enzyme:substrate ratio) at 37°C for 16 hours

LC-MS Conditions:

- Flow Rate: 0.3 mL/min

- Column Temperature: 45°C

- Gradient: 2-35% B over 90 minutes

- Ionization: ESI positive mode

- Mass Range: 300-2000 m/z

Data Analysis: Use software to identify peptides by comparing experimental masses with theoretical digests. Monitor specific PTMs including oxidation (M+16), deamidation (N/Q+1), and glycosylation using extracted ion chromatograms.

Protocol 3: HPTLC Method for Herbal Formulation Standardization

Objective: To develop a fingerprint profile for quality control of a complex herbal formulation.

Materials:

- HPTLC Plates: Silica gel 60 F254, 10 × 10 cm

- Sample Application: Automated applicator (e.g., CAMAG Linomat 5)

- Mobile Phase: Chloroform:methanol:water (70:30:4, v/v/v)

- Detection: Derivatization with anisaldehyde-sulfuric acid reagent

- Documentation: CAMAG HP-TLC Visualisation Analyser system [18]

Methodology:

- Pre-wash plates with methanol and activate at 110°C for 20 minutes

- Apply standard and sample solutions as 8-mm bands, 10 mm from plate bottom

- Develop in a saturated twin-trough chamber to a distance of 80 mm

- Dry plates and derivatize with detection reagent

- Heat at 100°C for 5 minutes until bands appear

- Capture images under UV 254 nm, UV 366 nm, and white light

- Perform densitometric scanning at 530 nm

Validation Parameters: Calculate Rf values for characteristic bands and establish a reference fingerprint for comparison with test samples. Method specificity is demonstrated by resolution of critical markers and consistency of fingerprint patterns across batches.

Visualizing Chromatographic Method Selection

Decision Framework for Chromatographic Method Selection

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Chromatographic Analysis of Biopharmaceuticals

| Reagent/Material | Function | Specificity/Safety Consideration | Example Products |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inert HPLC Columns | Minimizes metal-sensitive analyte adsorption | Enhances recovery of phosphorylated compounds, improves patient safety by accurate impurity quantification | Halo Inert, Restek Inert [4] |

| Superficially Porous Particles | Improves separation efficiency for biomolecules | Provides enhanced peak shape for basic compounds, better quantification of critical quality attributes | Halo, Ascentis Express [4] |

| MS-Compatible Mobile Phase Additives | Enables LC-MS analysis without signal suppression | Volatile salts (ammonium formate) allow direct MS coupling for structural characterization | Formic acid, ammonium acetate |

| High-Purity Water/Organic Solvents | Mobile phase preparation | Reduces background noise, prevents column contamination, ensures reproducible retention times | HPLC-grade acetonitrile, methanol |

| Reference Standards | System suitability and method validation | Qualified standards ensure accurate identification and quantification of impurities and actives | USP, EP reference standards |

| Sample Preparation Kits | Desalting, enrichment, cleanup | Remove interfering matrix components, improve sensitivity and column lifetime | Solid-phase extraction cartridges, spin filters |

The fundamental relationship between analytical specificity, patient safety, and drug efficacy necessitates rigorous chromatographic method selection and implementation. HPLC/UHPLC provides robust quantitative analysis for purity and stability testing, while LC-MS offers unparalleled specificity for structural characterization and biomarker detection. HPTLC serves as a cost-effective solution for fingerprinting complex herbal formulations. The continuous innovation in column technologies, particularly inert hardware and specialized stationary phases, addresses specific analytical challenges in biopharmaceutical characterization. By implementing appropriate chromatographic methodologies with demonstrated specificity, researchers can ensure the quality, safety, and efficacy of biopharmaceutical products throughout their development lifecycle and manufacturing process.

Achieving Unambiguous Results: Modern Techniques and Strategic Applications

Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) has established itself as the preeminent analytical technique for applications demanding uncompromising specificity. This guide provides an objective comparison of LC-MS/MS performance against alternative methodologies, supported by experimental data and detailed protocols. Within the broader context of specificity testing in chromatographic methods research, we demonstrate how the hybrid separation-mass analysis architecture of LC-MS/MS delivers unparalleled selectivity in complex matrices. The data presented herein offer researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals a rigorous evidence base for selecting analytical approaches that meet the most stringent specificity requirements across pharmaceutical, clinical, and environmental applications.

Analytical specificity—the ability to accurately measure an analyte in the presence of interfering components—represents a fundamental challenge in chemical measurement science. In pharmaceutical analysis, lack of specificity can lead to inaccurate potency assessments, missed impurity profiles, and compromised product quality. In clinical diagnostics, non-specific methods may generate false positives or negatives with direct implications for patient care. While various chromatographic and immunoassay techniques offer reasonable selectivity for many applications, increasingly complex samples and stringent regulatory requirements have pushed conventional methods to their performance limits.

LC-MS/MS addresses these challenges through a two-dimensional separation paradigm that combines the physicochemical separation power of liquid chromatography with the mass-based discrimination capabilities of tandem mass spectrometry. This dual separation mechanism provides an orthogonal filtering system that effectively eliminates isobaric and co-eluting interferences that confound single-dimension techniques. The technique's emergence as a gold standard for specificity is evidenced by its rapid adoption in diverse fields including pharmaceutical quality control, clinical diagnostics, environmental monitoring, and food safety [20] [23].

Fundamental Principles: The Architecture of Specificity

The exceptional specificity of LC-MS/MS stems from its multi-stage analytical workflow, which progressively filters chemical noise while preserving analyte signals. This process begins with liquid chromatographic separation, where compounds distribute between stationary and mobile phases based on their chemical properties, providing the first dimension of selectivity. Following ionization, typically by electrospray ionization (ESI) or atmospheric pressure chemical ionization (APCI), analytes enter the first mass analyzer (Q1), which acts as a mass-selective filter that excludes ions outside a narrow mass-to-charge (m/z) window.

The selected precursor ions then undergo collision-induced dissociation (CID) in a collision cell (Q2), generating characteristic product ions through controlled fragmentation. The second mass analyzer (Q3) then filters these product ions, providing a second mass-based selection step. This sequential mass filtering, combined with chromatographic retention time, creates a three-dimensional identifier (retention time → precursor mass → product mass) that delivers exceptional analytical specificity even in highly complex sample matrices [20] [24].

LC-MS/MS Specificity Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the multi-stage process that gives LC-MS/MS its exceptional specificity:

Performance Comparison: LC-MS/MS Versus Alternative Techniques

Specificity Comparison: LC-MS/MS vs. ELISA

The specificity advantages of LC-MS/MS become particularly evident when compared to immunoassay techniques such as Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA). While ELISA offers simplicity and throughput for some applications, its reliance on antibody-antigen interactions introduces significant specificity limitations, including cross-reactivity with structurally similar compounds. The following table summarizes the key specificity-related differences:

Table 1: Specificity Comparison of LC-MS/MS and ELISA

| Parameter | LC-MS/MS | ELISA |

|---|---|---|

| Recognition Principle | Mass-based structural identification | Antibody-antigen binding |

| Cross-Reactivity | Minimal (mass discrimination) | Common with similar epitopes |

| Molecular Differentiation | Can distinguish isoforms & metabolites | Often unable to distinguish closely related molecules |

| Matrix Interference Resistance | High (multiple separation dimensions) | Moderate (limited separation) |

| Structural Modification Detection | High sensitivity to modifications | Often insensitive to small modifications |

| Method Development Control | Systematic optimization | Dependent on antibody quality |

LC-MS/MS provides direct molecular characterization based on physical properties (mass, fragmentation pattern), whereas ELISA offers indirect measurement through molecular recognition elements whose specificity is inherently limited by antibody cross-reactivity [25]. This distinction becomes critical when analyzing complex biological samples containing numerous structurally related compounds, such as drug metabolites or protein isoforms, where antibody cross-reactivity can generate falsely elevated results.

Specificity Comparison Across Chromatographic Techniques

Different chromatographic techniques offer varying levels of specificity, with LC-MS/MS providing the highest overall discrimination capability:

Table 2: Specificity Comparison Across Chromatographic Techniques

| Technique | Separation Dimensions | Detection Principle | Specificity Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| HPLC-UV/Vis | Chromatographic (1D) | UV/Vis absorbance | Co-eluting compounds with similar λmax |

| HPLC-Fluorescence | Chromatographic (1D) | Fluorescence emission | Limited to native/derivatized fluorophores |

| GC-MS | Chromatographic + mass (2D) | Electron impact MS | Limited to volatile/derivatizable compounds |

| LC-MS | Chromatographic + mass (2D) | ESI/APCI MS | Isobaric compound interference |

| LC-MS/MS | Chromatographic + mass + mass (3D) | Tandem MS | Highest specificity; minimal limitations |

The triple selectivity of LC-MS/MS (chromatographic retention time, precursor mass, and product mass) provides an orthogonal filtering system that cannot be matched by single-dimension techniques. While GC-MS offers excellent specificity for volatile compounds, LC-MS/MS extends this capability to a much broader range of analytes, including thermally labile and high molecular weight compounds [23].

Experimental Protocols: Assessing Specificity

Protocol for Specificity Evaluation in Complex Matrices

Objective: To demonstrate LC-MS/MS specificity by quantifying target analytes in complex biological matrices with minimal interference.

Materials and Reagents:

- Matrix: Appropriate biological fluid (plasma, urine, tissue homogenate)

- Analytes: Target compounds and potential interferents

- Internal Standards: Stable isotope-labeled analogs of target analytes

- Extraction Solvents: Methanol, acetonitrile, ethyl acetate

- Mobile Phases: A: 0.1% formic acid in water; B: 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile

Instrumentation:

- LC System: UHPLC capable of binary or quaternary gradients

- Mass Spectrometer: Triple quadrupole MS with ESI or APCI source

- Column: Reversed-phase C18 column (100 × 2.1 mm, 1.7-2.7 μm)

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Extract analytes from matrix using protein precipitation (1:3 sample:acetonitrile)

- Chromatographic Separation:

- Column temperature: 40°C

- Flow rate: 0.3-0.6 mL/min

- Gradient: 5-95% B over 5-10 minutes

- Mass Spectrometric Detection:

- Multiple Reaction Monitoring (MRM) transitions optimized for each analyte

- Dwell time: 10-50 ms per transition

- Collision energies optimized for each transition

- Specificity Assessment:

- Analyze blank matrix to confirm absence of interference at target retention times

- Analyze matrix spiked with structurally similar compounds to evaluate discrimination capability

- Verify consistent retention times (±0.1 min) and ion ratios (±20%) across samples

Data Analysis: Specificity is demonstrated when:

- Signal in blank matrix < 20% of lower limit of quantification (LLOQ)

- No significant interference (>5% peak area contribution) at target retention times

- Ion ratios within specified limits across calibration range [24] [26]

Case Study: Host Cell Protein Quantitation

A recent study demonstrated LC-MS/MS specificity for detecting host cell proteins (HCPs) in biopharmaceutical products. The method successfully identified and quantified 67 HCPs at concentrations as low as 5-50 ppm in the presence of the therapeutic protein at 50 mg/mL (a 10,000:1 dynamic range). This level of specificity was unattainable with immunoassays due to antibody cross-reactivity limitations. The LC-MS/MS approach provided both identification and quantification in a single analysis, showcasing its dual qualitative and quantitative capabilities for complex specificity challenges [26].

Current Instrumentation and Technological Advances

Recent advancements in LC-MS/MS instrumentation have further enhanced analytical specificity:

Table 3: Recent LC-MS/MS Instrumentation Advancements (2024-2025)

| Manufacturer | Instrument | Specificity-Enhancing Features |

|---|---|---|

| Sciex | 7500+ MS/MS | 900 MRM/sec capability for increased multiplexing |

| Bruker | timsTOF Ultra 2 | Trapped ion mobility for 4D separations |

| Thermo Fisher | Orbitrap Astral MS | High resolution (>500,000) for isobar separation |

| Agilent | InfinityLab Pro iQ Series | Intelligent system optimization |

| Shimadzu | LCMS-8060RX | Advanced collision cell technology |

The incorporation of ion mobility separation adds a fourth dimension to LC-MS/MS analyses, enabling separation of isobaric compounds with identical precursor and product ions but different collision cross-section (size and shape). Instruments like the Bruker timsTOF Ultra 2 provide this additional separation dimension, pushing specificity boundaries even further [27].

High-resolution accurate mass (HRAM) instruments like the Orbitrap Astral provide resolution exceeding 500,000, enabling discrimination of compounds differing in mass by mere millidaltons. This level of mass accuracy virtually eliminates isobaric interference, representing the current pinnacle of mass-based specificity [23] [27].

Applications Demonstrating Specificity Advantages

Clinical Diagnostics

In clinical diagnostics, LC-MS/MS has become the reference method for analytes requiring high specificity, including:

- Vitamin D metabolite profiling: Differentiation of 25-hydroxyvitamin D2 and D3 isoforms, which immunoassays frequently fail to distinguish

- Testosterone and steroid hormone panels: Accurate quantification at low concentrations without cross-reactivity from similar steroids

- Therapeutic drug monitoring: Specific measurement of parent drugs and metabolites in complex matrices

- Newborn screening: Multiplexed analysis of amino acids and acylcarnitines with minimal false positives

The multiplexing capability of LC-MS/MS allows simultaneous quantification of dozens of analytes in a single injection without sacrificing specificity, a significant advantage over techniques requiring separate assays for each analyte [28] [29].

Pharmaceutical Analysis

In pharmaceutical quality control and development, LC-MS/MS specificity enables:

- Impurity profiling: Detection and identification of structurally related compounds at 0.1% levels

- Metabolite identification: Structural characterization of biotransformation products in complex biological matrices

- Biologics characterization: Analysis of post-translational modifications and degradation products

- Residual host cell protein detection: Specific identification and quantification as demonstrated in USP 1132.1 [26]

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful LC-MS/MS specificity studies require carefully selected reagents and materials:

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for LC-MS/MS Specificity Workflows

| Reagent/Material | Function | Specificity Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Internal Standards | Normalization of extraction and ionization variance | Distinguishable mass prevents interference with analytes |

| High-Purity Mobile Phase Additives | Modulate chromatography and ionization | Reduce chemical noise and background interference |

| Solid-Phase Extraction Cartridges | Sample cleanup and preconcentration | Remove matrix interferents while retaining analytes |

| Bioinert LC Systems | Minimize metal adsorption | Improve peak shape and reduce tailing |

| High-Efficiency LC Columns | Chromatographic separation | Resolve analytes from isobaric interferents |

LC-MS/MS represents the current gold standard for analytical specificity across diverse applications and matrices. Its triple-selectivity paradigm—combining chromatographic separation, precursor mass selection, and product mass verification—provides an unmatched capability to distinguish target analytes from potentially interfering compounds. While techniques like ELISA offer simplicity and HPLC-UV provides cost-effectiveness for less demanding applications, neither can match the discrimination power of LC-MS/MS for complex specificity challenges.

As instrumentation continues to advance with incorporation of ion mobility separation and higher mass resolution, the specificity advantages of LC-MS/MS will further expand. For researchers and method developers working with complex matrices, structurally similar compound mixtures, or stringent regulatory requirements, LC-MS/MS provides the specificity assurance necessary for confident analytical results.

In chromatographic analysis, what appears as a single, symmetrical peak may conceal multiple co-eluting compounds, leading to inaccurate quantitative results and flawed scientific conclusions. This fundamental challenge makes peak purity assessment a critical requirement in analytical method development, particularly for pharmaceutical analysis where it directly impacts drug safety and efficacy. The hyphenation of High-Performance Liquid Chromatography with Diode Array Detection (HPLC-DAD) provides a powerful solution to this challenge by combining superior separation capabilities with sophisticated spectral analysis. Within regulated pharmaceutical development, demonstrating peak purity is mandatory under ICH guidelines (Q3A-Q3D) for impurities in new drug substances and products [30]. The consequences of incomplete peak purity assessment can be severe, as illustrated by historical cases where one enantiomer provided therapeutic benefit while its counterpart caused toxicity, such as (S)-(+)-naproxen for arthritis treatment versus its enantiomer that causes liver poisoning [30].

Theoretical Foundations of HPLC-DAD Peak Purity Assessment

How HPLC-DAD Works

HPLC-DAD represents a hyphenated technique that combines the superior separation power of high-performance liquid chromatography with the multi-wavelength detection capabilities of a diode array detector. Unlike conventional UV detectors that measure at a single wavelength, the DAD simultaneously captures full UV spectra for every point throughout the chromatographic run [31]. This enables continuous spectral acquisition as compounds elute from the column, providing a three-dimensional data matrix (absorbance, wavelength, and time) that forms the basis for peak purity assessment [30].

The DAD operates by passing polychromatic light through the sample flow cell, then dispersing the transmitted light onto an array of photodiodes, typically measuring from 190 to 800 nm [31]. This allows the detector to capture the complete ultraviolet spectrum of each eluting compound without the need for multiple injections or wavelength programming. The resulting data richness enables both identification via spectral matching and purity assessment through spectral comparison across a chromatographic peak [32].

Principles of Spectral Peak Purity Assessment

The fundamental question in peak purity assessment is whether a chromatographic peak consists of a single chemical compound or multiple co-eluted components. HPLC-DAD addresses this by evaluating spectral homogeneity throughout the peak [30]. The theoretical basis relies on treating each acquired spectrum as a vector in n-dimensional space, where 'n' corresponds to the number of data points in the spectrum [30].

Spectral similarity is quantified using vector algebra by calculating the angle between spectra vectors or the correlation coefficient between spectra. For two spectra represented as vectors a and b, the spectral similarity is calculated as the cosine of the angle θ between them:

[ \cos \theta = \frac{\mathbf{a} \cdot \mathbf{b}}{\|\mathbf{a}\|\|\mathbf{b}\|} ]

An alternative approach uses the correlation coefficient between two spectra:

[ r = \frac{\sum{i=1}^{n}(ai - \bar{a})(bi - \bar{b})}{\sqrt{\sum{i=1}^{n}(ai - \bar{a})^2\sum{i=1}^{n}(b_i - \bar{b})^2}} ]

When vectors are mean-centered, these two measures of similarity are equivalent [30]. Perfectly identical spectra yield a correlation coefficient of 1 (θ = 0°), while completely dissimilar spectra produce a coefficient of 0 (θ = 90°). In practice, thresholds are established where a match factor above a specified value (e.g., 0.999) indicates spectral purity [33].

Table 1: Key Parameters in Spectral Peak Purity Assessment

| Parameter | Description | Impact on Purity Assessment |

|---|---|---|

| Spectral Contrast Angle (θ) | Angle between vector representations of spectra | Smaller angles indicate higher spectral similarity |

| Correlation Coefficient (r) | Statistical measure of spectral similarity | Values closer to 1.000 indicate pure peaks |

| Sensitivity Setting | Software parameter affecting threshold for impurity flag | Higher sensitivity makes purity assessment more stringent |

| Wavelength Range | Spectral region used for comparison | Should cover characteristic absorptions of analytes |

| Noise Threshold | Minimum spectral variance considered significant | Prevents noise from being misinterpreted as impurities |

Experimental Protocols for Peak Purity Assessment

Instrumentation and Method Setup

Successful peak purity assessment begins with proper instrumental configuration and method development. A typical HPLC-DAD system includes a binary or quaternary pump, autosampler, thermostatted column compartment, DAD detector, and data acquisition system running specialized software such as Agilent OpenLab CDS or Waters Empower [34] [35]. The analytical method must be carefully developed to achieve baseline separation of known components while allowing sufficient time for spectral acquisition.

Critical DAD parameters include:

- Spectral acquisition rate: Typically 5-20 spectra/second across the peak

- Spectral bandwidth: Usually 1-4 nm, balancing resolution and sensitivity

- Wavelength range: Typically 200-400 nm for most pharmaceuticals, covering UV chromophores

- Reference wavelength: Used for baseline correction, usually where analytes don't absorb

For pharmaceutical applications, method development typically involves screening columns of different selectivity (C18, C8, phenyl, cyano) and mobile phases at different pH values to achieve optimal separation [30]. The use of stressed samples (exposed to acid, base, peroxide, heat, and light) is essential to challenge the method's ability to separate degradation products from the main peak [30].

Step-by-Step Workflow for Peak Purity Analysis

The following workflow outlines a standardized approach to peak purity assessment using HPLC-DAD:

Method Development and Optimization: Develop a chromatographic method that provides baseline separation for known compounds. For the analysis of posaconazole, researchers optimized a gradient method using a Zorbax SB-C18 column with mobile phase acetonitrile:15 mM potassium dihydrogen orthophosphate (30:70 to 80:20) over 7 minutes at 1.5 mL/min flow rate [34].

System Suitability Testing: Establish that the HPLC-DAD system is performing adequately by verifying resolution, precision, and sensitivity criteria. This includes ensuring the absorbance does not exceed 1 AU at any detector wavelength to maintain linear response [33].

Data Acquisition: Inject samples and acquire full spectral data throughout the chromatographic run. For face mask analysis containing benzoyl peroxide, curcumin, and other actives, researchers employed a C18 column (250 × 4.6 mm, 5 μm) at 40°C with gradient elution, monitoring multiple wavelengths simultaneously [36].

Baseline Correction: Apply mathematical correction to remove baseline drift, ensuring accurate spectral comparison. The baseline is typically defined from peak start to stop limits [30].

Spectral Comparison: Software automatically compares spectra from upslope, apex, and downslope regions of each peak. In OpenLab CDS, this involves calculating a UV purity value based on match factors between these spectra [33].

Result Interpretation: Review purity flags and match factors. Peaks with match factors above the established threshold (after adjusting sensitivity settings) are considered pure, while those below indicate potential co-elution [33].

Figure 1: HPLC-DAD Peak Purity Assessment Workflow

Data Interpretation and Troubleshooting

Interpreting peak purity results requires both scientific understanding and practical experience. A low UV purity value indicates potential co-elution of compounds with significantly different UV spectra [33]. However, several limitations must be considered: