Specificity, Selectivity, Accuracy, and Precision: A Comprehensive Guide to Analytical Method Validation in Pharmaceutical Development

This article provides a thorough examination of the core validation parameters—specificity, selectivity, accuracy, and precision—in analytical method development for pharmaceutical research and drug development.

Specificity, Selectivity, Accuracy, and Precision: A Comprehensive Guide to Analytical Method Validation in Pharmaceutical Development

Abstract

This article provides a thorough examination of the core validation parameters—specificity, selectivity, accuracy, and precision—in analytical method development for pharmaceutical research and drug development. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and industry professionals, it explores the foundational definitions, methodological applications, and troubleshooting strategies as per ICH Q2(R2), USP, and other global guidelines. The content bridges theoretical concepts with practical case studies, addresses phase-appropriate validation from early discovery to commercialization, and discusses emerging trends such as Analytical Quality by Design (AQbD) and green chemistry to equip the audience with the knowledge to ensure regulatory compliance, data integrity, and robust analytical performance.

Core Principles: Demystifying Specificity, Selectivity, Accuracy, and Precision in Analytical Method Validation

In the rigorous world of research and drug development, the integrity of data is paramount. Conclusions and decisions are only as sound as the methods used to gather and analyze information. Within this context, a clear understanding of key validation parameters—specificity, selectivity, accuracy, and precision—forms the bedrock of trustworthy science. These concepts are the pillars that support the entire structure of research validity, ensuring that findings are not only statistically significant but also meaningful and reflective of reality.

Confusion often arises between the terms specificity and selectivity, as well as between accuracy and precision. While sometimes used interchangeably in casual conversation, they hold distinct and critical meanings in a scientific setting. This guide provides a detailed, objective comparison of these fundamental parameters. By defining their roles, illustrating their differences with experimental data, and placing them within the broader framework of method validation, we aim to equip researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with the knowledge to critically evaluate and improve their analytical techniques.

Specificity vs. Selectivity: Discriminating Power in Analysis

The terms specificity and selectivity both relate to an analytical method's ability to distinguish the analyte of interest from other components in the sample. However, a nuanced difference exists, and understanding it is crucial for proper method validation.

Conceptual Definitions

Specificity is the absolute ability to assess unequivocally the analyte in the presence of components that may be expected to be present, such as impurities, degradants, or matrix components. It is often considered a binary parameter—a method is either specific or it is not. Specificity is the preferred term in guidelines like those from the International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) [1]. A specific method can unambiguously measure the analyte even when other substances are present.

Selectivity, on the other hand, refers to the extent to which a method can determine a particular analyte in a mixture without interference from other analytes or compounds in that mixture. It is a measure of the degree of this discrimination. As one source notes, "selectivity is a parameter that can be graded whereas specificity is absolute" [2]. A highly selective method can quantify multiple analytes simultaneously while reliably distinguishing each one.

Experimental Protocols and Evaluation

Establishing specificity/selectivity is a fundamental step in bioanalytical method validation. The general protocol involves analyzing samples that contain potential interferents and comparing the results to a control.

Detailed Methodology:

- Prepare Samples: Analyze a blank biological matrix (e.g., plasma, urine) to ensure no endogenous components interfere with the analyte's signal. Then, analyze the matrix spiked with the analyte at a relevant concentration (e.g., the Lower Limit of Quantification, LLOQ).

- Introduce Interferents: Spike the matrix with known impurities, degradants, metabolites, or co-administered drugs at their expected maximum concentrations.

- Chromatographic Analysis: For methods like HPLC or LC-MS, inject the prepared samples and evaluate the resulting chromatograms. The critical parameters to assess are:

- Resolution: The peaks for the analyte and potential interferents should be baseline resolved.

- Peak Purity: Using a diode array detector (DAD) or mass spectrometry (MS), confirm that the analyte peak is homogeneous and not co-eluting with another substance [1].

- Data Interpretation: The method is considered specific if the analyte response is unaffected by the presence of interferents and each analyte of interest is resolved from all others.

Comparative Data and Scenarios

The following table summarizes the core differences and applications of specificity and selectivity.

Table 1: Specificity and Selectivity at a Glance

| Parameter | Core Question | Analogy | Primary Application in Drug Development |

|---|---|---|---|

| Specificity | Can the method measure only the analyte, with no interference? | A key that opens only one lock. | Stability-indicating methods; quantifying a single active drug in the presence of its degradants [1]. |

| Selectivity | To what extent can the method distinguish between multiple analytes? | a sieve with perfectly sized holes that separates different grains. | Bioanalysis in clinical pharmacology; simultaneously quantifying a drug and its major metabolites in patient plasma [1]. |

Accuracy vs. Precision: Cornerstones of Measurement Truth and Reproducibility

Accuracy and precision are foundational concepts in evaluating the quality of measurements. They describe different aspects of measurement performance, and a reliable method must demonstrate both.

Conceptual Definitions

- Accuracy refers to the closeness of agreement between a measured value and a true or accepted reference value. It answers the question, "Is my result correct?" [3]. Accuracy is about correctness and freedom from bias.

- Precision refers to the closeness of agreement between a series of measurements obtained from multiple sampling of the same homogeneous sample under prescribed conditions. It answers the question, "Can I get the same result repeatedly?" [1] [3]. Precision is about reproducibility and consistency, regardless of whether the results are accurate.

Experimental Protocols and Evaluation

The validation of accuracy and precision in bioanalytical methods is typically conducted together through a study of repeatability (intra-day precision) and intermediate precision (inter-day precision, often involving different analysts or equipment).

Detailed Methodology for Accuracy and Precision Assessment:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare a minimum of five replicates per concentration level. The concentrations should cover the linear range of the method, typically including at least three levels: one near the LLOQ, one in the mid-range, and one near the upper limit of quantification (ULOQ) [1].

- Analysis: Analyze all samples using the validated method.

- Calculation:

- Accuracy: For each concentration level, calculate the mean measured value. Accuracy is expressed as the percentage recovery of the known added amount or as the relative bias. % Accuracy = (Mean Measured Concentration / Nominal Concentration) × 100%

- Precision: Calculate the standard deviation (SD) and relative standard deviation (RSD) for the replicates at each concentration level. The RSD, also known as the coefficient of variation (CV), is the primary metric for precision. % RSD = (Standard Deviation / Mean) × 100%

Comparative Data and the Bullseye Analogy

The classic bullseye analogy effectively illustrates the relationship between accuracy and precision.

Table 2: Interpreting Accuracy and Precision Combinations

| Scenario | Accuracy | Precision | Interpretation & Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| High Accuracy, High Precision | High | High | The ideal scenario. Results are both correct and consistent. The method is robust and reliable for decision-making. |

| High Accuracy, Low Precision | High | Low | The average of the results is correct, but individual measurements are scattered. The method has high bias but is not reliable for single measurements. |

| Low Accuracy, High Precision | Low | High | Results are consistently wrong in the same direction. This indicates a systematic error (bias) that may be correctable through calibration. |

| Low Accuracy, Low Precision | Low | Low | The worst scenario. Results are inconsistent and incorrect. The method is unreliable and requires re-development. |

In a research context, accuracy is paramount when the actual value is critical, such as in determining the dosage of a drug based on its concentration in a formulation. Precision is more critical when consistency is the primary goal, such as in manufacturing quality control to ensure every product unit is identical [3].

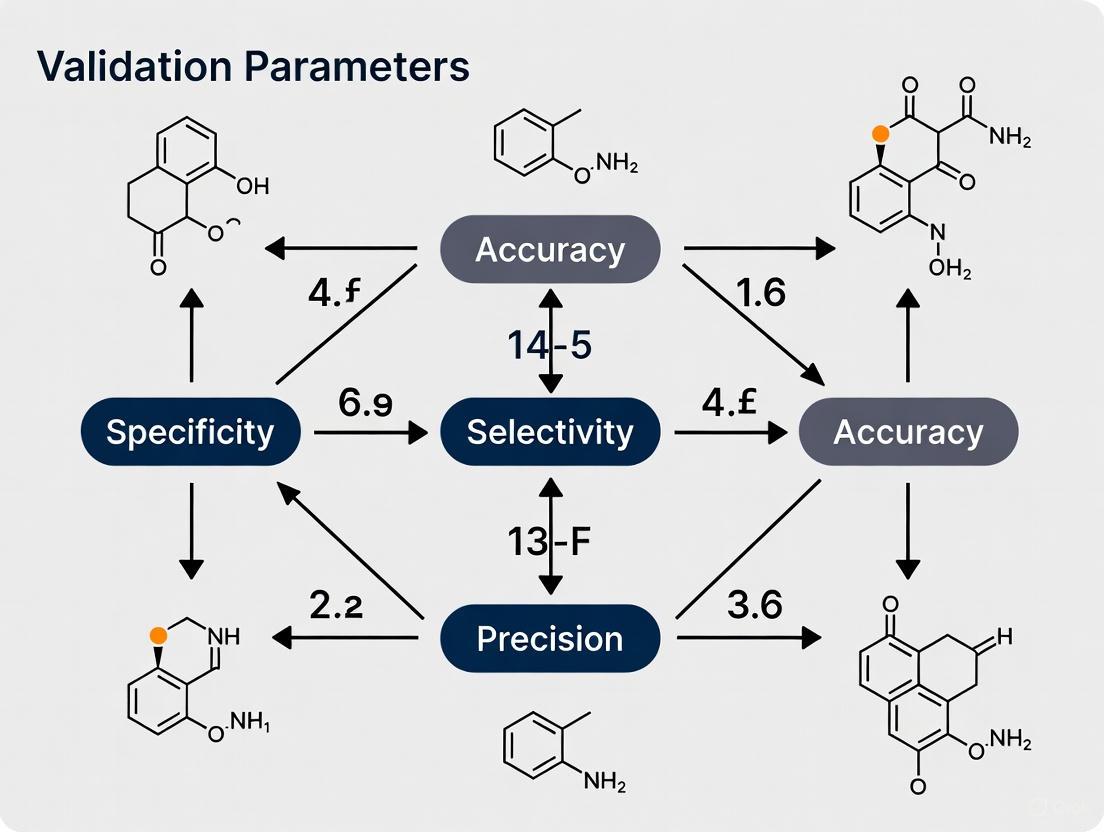

The Interconnected Framework: A Visual Synthesis

The relationships between the four pillars and their role in method validation can be visualized as a cohesive workflow. The following diagram maps the logical pathway from establishing the fundamental discriminatory power of a method to ensuring its quantitative reliability.

Diagram 1: The pillars of analytical method validation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

The following table details key reagents and materials essential for conducting validation experiments for the parameters discussed in this guide.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Method Validation

| Reagent/Material | Function in Validation | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Certified Reference Standard | Provides the true/accepted value against which accuracy is measured. Must be of high and documented purity. | Used to prepare known concentration solutions for accuracy and linearity studies [1]. |

| Blank Biological Matrix | Used to assess specificity by confirming the absence of interfering signals from endogenous components. | Control human plasma or urine in bioanalytical method development [1]. |

| Spiked Matrix Samples | Samples with known concentrations of analyte(s) and potential interferents, used to validate specificity, selectivity, accuracy, and precision. | Plasma samples spiked with a drug candidate and its known metabolites to establish selectivity [1]. |

| Chromatographic Columns | The stationary phase for separation; critical for achieving the resolution needed for specificity and selectivity. | A C18 column used in HPLC to separate a drug from its degradants in a stability-indicating method. |

| Mass Spectrometer (MS) | A detection system that provides high selectivity and specificity by identifying analytes based on their mass-to-charge ratio. | LC-MS is used in bioanalysis to specifically quantify a drug in complex biological samples like blood [1]. |

For researchers and drug development professionals, navigating the regulatory requirements for analytical procedure validation is fundamental to ensuring drug quality, safety, and efficacy. The landscape is primarily shaped by three key sets of guidelines: the International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) Q2(R2) guideline, the United States Pharmacopeia (USP) General Chapter <1225>, and the directives from the European Medicines Agency (EMA). While aligned in their overall goal, these guidelines exhibit critical differences in their structure, terminology, and emphasis, which can impact strategic regulatory planning. A solid understanding of the validation parameters—including specificity, selectivity, accuracy, and precision—across these frameworks is not merely a regulatory exercise but a cornerstone of robust analytical science. The recent adoption of the new ICH Q2(R2) guideline in 2023 marks a significant evolution, moving the industry from a static validation model toward a more dynamic, lifecycle approach inspired by Analytical Quality by Design (AQbD) principles [4] [5].

Comparative Analysis of ICH, USP, and EMA Guidelines

The following table provides a detailed, side-by-side comparison of the core validation parameters as defined by the ICH, USP, and EMA guidelines, highlighting the nuances in their definitions and requirements.

Table 1: Comparison of Core Validation Parameters Across ICH Q2(R2), USP, and EMA

| Validation Parameter | ICH Q2(R2) | USP General Chapter <1225> | EMA / EU GMP Annex 15 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | Closeness of agreement between a test result and the accepted reference value [4]. | Closeness of test results obtained by that method to the true value [6]. | Expects demonstration of accuracy, typically through spike/recovery experiments, aligning with ICH principles [7]. |

| Precision | Expressed as repeatability, intermediate precision, and reproducibility. Assessed with a minimum of 9 determinations over 3 levels [6] [4]. | Degree of agreement among individual test results from repeated measurements. Expresses as standard deviation or relative standard deviation [6]. | Requires precision to be demonstrated, with a strong emphasis on the use of statistical process control and trend analysis in ongoing verification [8] [7]. |

| Specificity/Selectivity | Ability to assess unequivocally the analyte in the presence of components that may be expected to be present [6]. ICH prefers "specificity" [6]. | USP notes that other international authorities prefer "selectivity," reserving "specificity" for procedures that are completely selective [6]. | Requires specific procedures to demonstrate specificity, particularly for stability-indicating methods [7]. |

| Detection Limit (DL) | The lowest amount of analyte in a sample that can be detected, but not necessarily quantitated [6]. | Defined similarly to ICH. For instrumental methods, a signal-to-noise ratio of 2:1 or 3:1 is common [6]. | Expects the DL to be established for impurities, aligning with ICH Q2(R2) [7]. |

| Quantitation Limit (QL) | The lowest amount of analyte in a sample that can be quantitatively determined with suitable precision and accuracy [6]. | Defined similarly to ICH. A typical signal-to-noise ratio is 10:1 [6]. | Expects the QL to be established, consistent with ICH requirements [7]. |

| Linearity & Range | Linearity is replaced by "Reportable Range" and "Working Range" in Q2(R2), which includes suitability of the calibration model and verification of the lower range limit [4]. | Linearity: Ability to obtain test results proportional to analyte concentration. Range: Interval between upper and lower levels of analyte that has been demonstrated to be determined with precision, accuracy, and linearity [6]. | Requires demonstration of linearity and defines a suitable range for the procedure, consistent with the ICH foundation [7]. |

| Robustness | A new section in Q2(R2) provides more detailed guidance on robustness study design, recommending structured approaches like Design of Experiments (DoE) [4] [5]. | Measures capacity to remain unaffected by small, deliberate variations in method parameters [6]. | Strongly encourages robustness testing during method development, often as part of an AQbD approach, to ensure method reliability [7]. |

| Key Differentiators | - Lifecycle approach linked with ICH Q14 [5].- Covers modern analytical techniques (e.g., NIR, MS) [4].- Introduces "Analytical Procedure Lifecycle" [4]. | - Legally recognized standard in the US (FD&C Act) [6].- Distinguishes between validation, verification, and transfer [9].- User verification required for compendial methods [6]. | - Mandates a Validation Master Plan (VMP) [8] [7].- Integrated with EU GMP, particularly Annex 15 [8].- Emphasizes ongoing process verification (OPV) post-approval [8]. |

Key Strategic Implications of the Differences

The differences outlined in Table 1 have direct implications for regulatory strategy. The EMA's requirement for a Validation Master Plan creates a structured, top-down framework for all validation activities, which is more formal than the FDA's expectations [8]. Furthermore, the EMA's concept of Ongoing Process Verification (OPV) is integrated into the product quality review, emphasizing continuous monitoring rather than a one-time validation event [8]. With the advent of ICH Q2(R2), a major shift is the move from a static "validate once" approach to an Analytical Procedure Lifecycle model. This new paradigm, developed in parallel with ICH Q14, formalizes AQbD concepts such as the Analytical Target Profile (ATP) and Method Operable Design Region (MODR), enabling more flexible and robust method management post-approval [4] [5].

Experimental Protocols for Key Validation Parameters

To ensure robust and defensible method validation, standardized experimental protocols are essential. The following sections detail the general methodologies for establishing key validation parameters, synthesized from the ICH, USP, and EMA guidelines.

Protocol for Accuracy

The protocol for accuracy varies based on the sample type [6].

For Drug Substances:

- Sample Preparation: Analyze a minimum of 9 determinations over a minimum of 3 concentration levels (e.g., 80%, 100%, 120% of target concentration). Use a known purity reference standard.

- Comparison: Compare the measured value against the accepted true value of the reference standard.

- Calculation: Calculate accuracy as the percentage of recovery. Report the mean recovery and confidence intervals (e.g., %RSD) across all levels.

For Drug Products (Formulated):

- Sample Preparation: Use a placebo matrix (all components except the analyte). Spike with known quantities of the analyte across the specified range (3 levels, 3 replicates each).

- Analysis: Carry the spiked samples through the complete analytical procedure.

- Calculation: Calculate the percentage recovery of the known, added amount. The results demonstrate the ability of the method to accurately measure the analyte in the presence of the sample matrix.

Protocol for Precision

Precision should be investigated at multiple levels [6].

Repeatability:

- Sample Preparation: Use a homogeneous sample of drug substance or product (e.g., 100% test concentration).

- Analysis: Perform a minimum of 6 independent assays of the same sample. These must be complete, independent sample preparations taken through the entire analytical procedure.

- Calculation: Calculate the standard deviation (SD) or relative standard deviation (RSD) of the 6 results.

Intermediate Precision:

- Experimental Design: Vary conditions within the same laboratory, such as different analysts, different days, and different equipment.

- Analysis: Perform the assay under each of the varied conditions.

- Calculation: Evaluate the SD or RSD of the results from all conditions to establish the method's robustness to within-laboratory variations.

Protocol for Specificity/Selectivity

Specificity must be demonstrated for identification tests, purity tests, and assays [6].

- For an Impurity or Assay Method:

- Sample Preparation:

- A: Analyte alone (e.g., drug substance reference standard).

- B: Placebo or sample matrix.

- C: Sample spiked with potential impurities, degradation products (generated via stress studies: light, heat, humidity, acid/base hydrolysis, oxidation), or excipients.

- Analysis: Analyze all samples (A, B, C) using the proposed analytical procedure.

- Evaluation: For chromatography, demonstrate that the analyte peak is free from interference and that all critical peaks (e.g., impurities) are resolved. Peak purity tests using techniques like diode array detection (DAD) or mass spectrometry (MS) are highly recommended to prove the analyte peak is attributable to a single component [6].

- Sample Preparation:

Visualizing the Analytical Procedure Lifecycle

The revised ICH Q2(R2) and ICH Q14 guidelines introduce a fundamental shift from a one-time validation event to an integrated lifecycle management approach for analytical procedures. The following diagram illustrates this continuous process.

Diagram 1: Analytical Procedure Lifecycle per ICH Q14/Q2(R2)

This lifecycle model underscores that knowledge gained during routine use of the method, through ongoing monitoring and data trending, feeds back into the development and validation stages, enabling continuous improvement and facilitating managed post-approval changes within the established MODR [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagent Solutions

The execution of validation studies requires specific high-quality materials. The table below details key reagent solutions and their critical functions in ensuring reliable analytical results.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Validation Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function in Validation |

|---|---|

| Reference Standards | Certified materials with known purity and identity; used as the primary benchmark for quantifying the analyte and establishing method accuracy and linearity [6]. |

| System Suitability Solutions | Prepared mixtures used to verify that the chromatographic or analytical system is performing adequately at the time of testing, ensuring data integrity for parameters like precision and specificity [6]. |

| Placebo/Blank Matrix | Contains all components of the sample except the analyte; critical for demonstrating specificity/selectivity by proving the absence of interference from the sample matrix [6]. |

| Impurity/Degradation Standards | Isolated impurities or forced-degradation products; used to spike samples to confirm the method's ability to detect and quantify impurities, a key aspect of specificity [6]. |

| Buffers & Mobile Phases | High-purity solvents and salts prepared to exact specifications; their consistency is vital for maintaining robust separation and detector response, directly impacting precision, accuracy, and robustness [6]. |

The regulatory landscape for analytical validation parameters is a complex but coherent tapestry woven from the ICH, USP, and EMA guidelines. While the core parameters of specificity, accuracy, and precision are universally required, the strategic approach to demonstrating them is evolving. The USP provides a foundational, legally-recognized standard in the US, the EMA enforces a structured, plan-driven framework integrated with GMP, and the new ICH Q2(R2) ushers in a modern, lifecycle-oriented era. For drug development professionals, success lies in understanding the nuanced differences between these guidelines and implementing a holistic, science- and risk-based validation strategy. Embracing the Analytical Procedure Lifecycle model, with its emphasis on ATP, MODR, and continuous improvement, is no longer just a best practice but is becoming the expected standard for ensuring analytical methods remain fit-for-purpose throughout a product's life.

The Critical Role of Validated Methods in Drug Safety, Efficacy, and Quality Control

In the pharmaceutical industry, the validation of analytical methods is not merely a regulatory hurdle but a fundamental scientific requirement that forms the bedrock of drug safety, efficacy, and quality control. Method validation is a systematic process of performing numerous tests designed to verify that an analytical test system is suitable for its intended purpose and capable of providing useful and valid analytical data [10]. This process establishes evidence that provides a high degree of assurance that a specific process, method, or system will consistently produce results meeting predetermined acceptance criteria [11].

The critical importance of validated methods extends across the entire drug development and manufacturing continuum. From raw material testing to finished product release, validated methods ensure that medications are free from contamination and impurities, protecting patients from adverse effects while guaranteeing that drugs deliver their optimal therapeutic benefits [12]. Within the context of global regulatory frameworks, method validation provides the necessary documentation to demonstrate compliance with standards set by agencies including the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), European Medicines Agency (EMA), and the International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH) [13].

As the pharmaceutical landscape evolves toward more complex molecules and innovative therapies, the role of validated methods becomes increasingly crucial. This article examines the core parameters of method validation, explores their application in ensuring drug safety and efficacy, and highlights emerging trends that are reshaping quality control practices for 2025 and beyond.

Core Parameters of Analytical Method Validation

Essential Validation Characteristics and Their Significance

Analytical method validation involves testing multiple attributes to demonstrate that a method can provide reliable and valid data when used routinely [10]. These parameters are systematically evaluated to establish that analytical methods are fit for their intended purpose in pharmaceutical analysis.

Table 1: Core Parameters for Analytical Method Validation

| Parameter | Definition | Methodological Approach | Acceptance Criteria |

|---|---|---|---|

| Specificity/Selectivity | Ability to measure analyte accurately in presence of potential interferences | Analyze chromatographic blanks; check for interference in expected analyte retention time window | No interference peaks at analyte retention time [10] |

| Accuracy | Degree of agreement between test results and true value | Spike sample matrix with known analyte concentrations; calculate % recovery | Varies by matrix; detailed in study plan [10] |

| Precision | Degree of agreement among individual test results from multiple samplings | Inject series of standards/samples; calculate %RSD from mean and standard deviation | Often based on Horwitz equation (e.g., 1.9% RSDr for 10% analyte) [10] |

| Linearity | Ability to obtain results proportional to analyte concentration | Inject minimum 5 concentrations (50-150% of expected range); plot concentration vs. response | Correlation coefficient (r) with specified minimum [10] |

| Range | Interval between upper and lower analyte levels demonstrated with precision, accuracy, and linearity | Confirm using concentrations from linearity testing | Established based on linearity results [10] |

| LOD/LOQ | Lowest concentrations detectable (LOD) and quantifiable (LOQ) | Calculate from linear regression (LOD=3.3σ/S, LOQ=10σ/S) or signal-to-noise (3:1 for LOD, 10:1 for LOQ) | Expressed in μg/mL or ppm; specific to method [10] |

| Robustness | Capacity to remain unaffected by small, deliberate variations in method parameters | Vary parameters (pH, temperature, mobile phase composition); measure impact on results | Consistent performance under varied conditions [13] |

The mathematical foundation for several validation parameters relies on statistical analysis. For precision evaluation, the Horwitz equation provides an empirical relationship between the among-laboratory relative standard deviation (RSD) and concentration (C): RSDR = 2(1-0.5logC) [10]. For estimation of repeatability (RSDr), this is modified to RSDr = 0.67 × 2(1-0.5logC). This equation has been proven to be largely independent of analyte, matrix, and method of evaluation across a wide concentration range [10].

Experimental Protocols for Key Validation Parameters

Protocol for Linearity Determination:

- Prepare a series of standard solutions at a minimum of five different concentrations covering 50-150% of the expected working range.

- Inject each solution in duplicate or triplicate using the specified chromatographic conditions.

- Record the instrument response (peak area) for each concentration.

- Plot concentration versus response and calculate the regression line using the equation y = a + bx.

- Calculate the correlation coefficient (r) to confirm linearity [10].

Protocol for Accuracy Evaluation:

- Prepare samples of the matrix of interest spiked with known concentrations of analyte standard.

- Analyze the samples using the method being validated.

- Calculate the percentage recovery for each concentration using the formula: % Recovery = (Measured Concentration / Theoretical Concentration) × 100.

- Compare results against predetermined acceptance criteria specified in the study plan [10].

Protocol for LOD/LOQ Determination from Linear Regression:

- Prepare a series of standard solutions at various concentrations covering the working range.

- Analyze each solution minimally twice and record instrument responses.

- Calculate the linear regression equation y = a + bx.

- Calculate the standard deviation of the residuals (σ).

- Calculate LOD as (3.3σ)/S and LOQ as (10σ)/S, where S is the slope of the calibration curve [10].

Analytical Method Validation in Pharmaceutical Quality Control

Integration into Pharmaceutical Quality Systems

Validated analytical methods form the technical foundation of robust pharmaceutical quality control systems, ensuring that every drug batch consistently meets predefined standards of identity, strength, purity, and quality [13]. The quality control process in the pharmaceutical industry follows a systematic, multi-stage approach that spans from raw materials to final product release.

Raw Material Testing: All primary raw materials including active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs), excipients, and packaging components are tested for identity, purity, and safety using sophisticated instrumental techniques such as chromatography (HPLC, UPLC) and spectroscopy (MS) [12]. This initial testing prevents contaminants from entering the production process and ensures consistency and reliability in downstream development [13].

In-Process Quality Control (IPQC): During manufacturing, critical process parameters including temperature, pH, and mixing speed are continuously monitored to detect deviations early [13]. These controls maintain batch consistency and minimize the risk of reprocessing. The implementation of Process Analytical Technology (PAT) enables real-time monitoring of Critical Quality Attributes (CQAs) and Critical Process Parameters (CPPs), allowing immediate adjustments during production rather than relying solely on end-product testing [12].

Finished Product Testing: Before release, every drug batch undergoes rigorous testing to verify it meets specifications for identity, strength, purity, and performance [13]. Common assessments include content uniformity, dissolution profiles, sterility, and impurity profiling using advanced methods like UPLC-MS/MS and elemental analysis [13]. Validated methods are essential for regulatory submissions and are required for all critical quality attributes tested during this stage.

Stability Testing: This examines how a drug's quality evolves under various environmental conditions throughout its shelf life [13]. Long-term and accelerated studies conducted under ICH guidelines require robust analytical follow-up with controlled storage, time-point analysis, and biomarker tracking to ensure ongoing safety and efficacy [13].

Quality Risk Management and Regulatory Alignment

Quality risk management in pharmaceuticals represents a proactive approach to identifying, assessing, and mitigating risks throughout manufacturing and quality control processes [13]. It is an integral part of a modern pharmaceutical quality system and is emphasized in ICH Q9 and Q10 guidelines, encompassing three key aspects:

- Risk assessment: Systematically evaluating potential sources of variability or failure in processes, equipment, and materials

- Risk control: Implementing measures to minimize or eliminate identified risks

- Risk review: Continuously monitoring and updating risk assessments as new information or technologies become available [13]

The Quality by Design (QbD) approach, outlined in ICH Q8, advocates for a science- and risk-based framework that emphasizes understanding the product and process from the earliest development stages [13]. This includes defining Critical Quality Attributes (CQAs), establishing critical process parameters, and developing validated analytical methods using UPLC-MS/MS, ICP-MS, and other advanced tools [13].

Table 2: Quality Control Stages and Corresponding Validated Methods

| QC Stage | Primary Quality Focus | Common Analytical Methods | Validation Parameters Emphasized |

|---|---|---|---|

| Raw Material Testing | Identity, purity, safety | HPLC, UPLC, MS, Spectroscopy | Specificity, Accuracy, LOD/LOQ [13] [12] |

| In-Process Control | Batch consistency, process parameters | PAT, Real-time sensors, pH, temperature monitoring | Precision, Robustness [12] |

| Finished Product Testing | Identity, strength, purity, performance | UPLC-MS/MS, Dissolution testing, Sterility testing, Elemental analysis | Accuracy, Precision, Specificity, Linearity [13] |

| Stability Testing | Shelf-life determination, degradation profiles | HPLC, MS, Forced degradation studies | Specificity, Accuracy, Precision [13] |

Drug Safety and Efficacy Assessment in Clinical Trials

Clinical Trial Methodology for Safety and Efficacy Evaluation

The assessment of drug safety and efficacy progresses through rigorously designed clinical trials that serve as the ultimate validation of a drug's therapeutic value. Clinical research in humans to evaluate the safety and efficacy of new drugs involves trials conducted in sequential phases [14]:

Phase 1 trials primarily evaluate safety and dosage in humans, typically involving 20-100 healthy volunteers. The goal is to determine the dose at which toxicity first appears and establish initial safety profiles [14].

Phase 2 trials assess efficacy in treating the target disease and further evaluate side effects. These studies involve several hundred people with the target disease and aim to determine optimal dose-response relationships while continuing safety assessment [14].

Phase 3 trials constitute large-scale studies (often hundreds to thousands of people) in more heterogeneous populations with the target disease. These studies compare the drug with existing treatments, placebos, or both to verify efficacy and detect adverse effects that may not have been apparent in earlier, smaller trials. Phase 3 trials provide the majority of safety data used for regulatory approval [14].

Phase 4 (postmarketing surveillance) occurs after FDA approval and includes formal research studies along with ongoing reporting of adverse effects. Phase 4 trials can detect uncommon or slowly developing adverse effects that are unlikely to be identified in smaller, shorter-term premarketing studies [14].

Methodological Challenges in Safety Assessment

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs), while considered the gold standard for establishing efficacy, face significant methodological challenges in comprehensively evaluating drug safety [15]:

Limited Statistical Power: Premarketing clinical trials are typically statistically underpowered to detect specific harms, either due to recruitment of low-risk populations or low intensity of event ascertainment [15]. The lack of statistical significance should not be interpreted as proof of clinical safety in an underpowered clinical trial. For example, the development program for varenicline largely excluded patients with psychiatric comorbidity and cardiovascular disease despite the high prevalence of these conditions among smokers [15].

Inadequate Ascertainment and Classification of Adverse Events: Inconsistencies in adverse effects reporting create substantial challenges. Adverse events are typically recorded as secondary outcomes in trials and are often not prespecified [15]. Misclassification is possible, particularly when outcomes are collected through spontaneous reports from trial participants rather than systematic monitoring.

Limited Generalizability: Clinical trial participants are often carefully selected, potentially excluding high-risk populations or those with comorbidities [15]. This lack of generalizability means that safety data may not extrapolate well to wider populations who may be taking different doses or formulations in real-world settings.

The Therapeutic Index (TI) has emerged as a key indicator illustrating the delicate balance between efficacy and safety, typically considered as the ratio of the highest non-toxic drug exposure to the exposure producing the desired efficacy [16]. Drugs with narrow TI (NTI drugs, TI ≤3) pose particular challenges, as tiny variations in dosage may result in therapeutic failure or serious adverse drug reactions [16]. Research has revealed that the targets of NTI drugs tend to be highly centralized and connected in human protein-protein interaction networks, with a greater number of similarity proteins and affiliated signaling pathways compared to targets of drugs with sufficient TI [16].

Diagram 1: Drug Efficacy-Safety Balance Assessment. This workflow illustrates the parallel evaluation of safety and efficacy throughout clinical development phases, culminating in the determination of the Therapeutic Index.

Emerging Trends and Future Directions

Innovative Approaches in Pharmaceutical Validation

As we approach 2025, pharmaceutical validation is undergoing a significant transformation, with companies leveraging innovative technologies and methodologies to ensure product quality and safety while improving efficiency [17]. Several key trends are shaping the future landscape:

Continuous Process Verification (CPV) represents an evolution from traditional validation approaches by focusing on ongoing monitoring and control of manufacturing processes throughout the product lifecycle [17]. Instead of relying solely on the traditional three-stage process validation framework, CPV emphasizes real-time data collection and analysis to continuously verify that processes remain in a state of control. Benefits include reduced downtime through early identification of potential issues, real-time quality control enabling immediate process adjustments, enhanced regulatory compliance, and reduced waste through more efficient production processes [17].

Data Integrity has become increasingly crucial as regulations become more stringent. Standards like ALCOA+ (Attributable, Legible, Contemporaneous, Original, and Accurate) have become critical to ensure all data is correctly managed and traceable [17]. Maintaining data integrity enhances trust with regulatory bodies and customers, reduces compliance issues through strong data management, and provides the foundation for accurate quality assessment [17].

Digital Transformation involves integrating advanced digital tools and automation to streamline processes, reduce manual errors, and improve efficiency [17]. This includes the implementation of digital twins, robotics, and Internet of Things (IoT) devices. Benefits include improved accuracy through minimized human error, efficiency gains from automated validation processes, and enhanced adaptability to respond faster to market demands and regulatory changes [17].

Real-Time Data Integration combines data from multiple sources into a single system, enabling pharmaceutical manufacturers to monitor production continuously and respond quickly to changes [17]. By integrating data across departments, companies gain comprehensive, up-to-date insights that inform immediate decision-making and adjustments during production, enhancing both quality and efficiency [17].

Advanced Predictive Models and Regulatory Science

The Advanced Research Projects Agency for Health (ARPA-H) has launched the Computational ADME-Tox and Physiology Analysis for Safer Therapeutics (CATALYST) program, which aims to create human physiology-based computer models to accurately predict safety and efficacy profiles for Investigational New Drug (IND) candidates [18]. This initiative addresses the fact that over 90% of drug candidates never reach the commercial market, with approximately half of these failures due to efficacy issues and a quarter resulting from safety issues occurring during clinical trials that were not predicted before first-in-human studies [18].

CATALYST seeks to lessen the use of insufficiently predictive preclinical animal studies with more accurate, faster, and cost-effective in silico drug development tools grounded in human physiology [18]. These technologies could significantly reduce the failure rate of drug candidates, ensure that medicines reaching clinical trials have confident safety profiles, and better protect trial participants. The program aims to reach clinical trial readiness based on validated, in silico safety data and help meet the targets of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration's Modernization Act [18].

Table 3: Emerging Trends in Pharmaceutical Validation for 2025

| Trend | Core Principle | Technological Enablers | Impact on Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Continuous Process Verification | Ongoing monitoring throughout product lifecycle | PAT, Real-time sensors, Data analytics | Shifts validation from periodic to continuous [17] |

| Advanced Data Integrity | ALCOA+ principles for complete data traceability | Blockchain, Electronic lab notebooks, Audit trails | Enhances data reliability and regulatory confidence [17] [12] |

| Digital Transformation | Integration of digital tools and automation | IoT, Robotics, Digital twins, AI | Reduces human error and improves efficiency [17] |

| Predictive Modeling | In silico prediction of safety and efficacy | AI, Machine learning, Physiological modeling | Potentially reduces preclinical animal studies [18] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Modern pharmaceutical validation relies on a suite of sophisticated reagent solutions and analytical technologies that enable precise characterization of drug products throughout development and manufacturing.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Pharmaceutical Validation

| Reagent Solution | Primary Function | Application Context | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chromatographic Reference Standards | Quantification and identification of analytes | HPLC, UPLC method development and validation | High purity, well-characterized, traceable to reference materials [13] |

| Mass Spectrometry Reagents | Enable ionization and detection in MS systems | UPLC-MS/MS impurity profiling, biomarker quantification | High purity, volatility compatible with MS systems, stable isotope labeling [13] |

| Process Analytical Technology (PAT) | Real-time monitoring of critical process parameters | In-process control during manufacturing | Non-destructive, real-time capability, robust in manufacturing environment [12] |

| Stability Testing Materials | Accelerated and long-term stability assessment | Forced degradation studies, shelf-life determination | Controlled storage conditions, ICH guideline compliance [13] |

| Quality Control Reference Materials | System suitability testing and method verification | Finished product testing, quality attribute verification | Documented traceability, appropriate expiration dating [13] [12] |

Diagram 2: Pharmaceutical Validation Technology Ecosystem. This diagram illustrates the interconnected analytical technologies and data systems that support validation activities across the pharmaceutical product lifecycle.

The critical role of validated methods in ensuring drug safety, efficacy, and quality control remains unquestionable in modern pharmaceutical development and manufacturing. As the industry continues to evolve, with increasing molecule complexity and regulatory expectations, the fundamental principles of method validation provide the necessary scientific foundation for reliable analytical data.

The comprehensive validation of analytical methods—encompassing specificity, accuracy, precision, linearity, and robustness—serves as an essential requirement for establishing the reliability of pharmaceutical testing methodologies [10]. When properly implemented within a quality risk management framework aligned with ICH guidelines, validated methods ensure that medications consistently meet predefined quality standards while protecting patient safety [13].

Looking toward the future, emerging trends including continuous process verification, digital transformation, and predictive modeling are poised to transform validation practices from discrete, documentation-heavy exercises to integrated, science-based processes that provide real-time quality assurance [17]. Initiatives such as the ARPA-H CATALYST program represent promising advances toward more predictive safety and efficacy assessment, potentially reducing the high failure rate of drug candidates in clinical development [18].

For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, maintaining expertise in both fundamental validation principles and emerging methodologies will be essential for navigating the evolving landscape of pharmaceutical quality. The ongoing harmonization of regulatory standards and adoption of innovative technologies will continue to shape validation practices, but the ultimate goal remains unchanged: to ensure that every pharmaceutical product reaching patients is safe, effective, and of consistently high quality.

In the pharmaceutical industry, the lifecycle of an analytical method is a continuous process that ensures reliable data generation from initial development through routine commercial use. A well-managed lifecycle is fundamental to decision-making in drug development, impacting everything from early-stage API synthesis to quality control of final marketed products [19] [20]. The modern approach to this lifecycle, often termed Analytical Procedure Lifecycle Management (APLM), moves beyond a simple linear path to an integrated framework emphasizing robustness, predictability, and continuous verification [21] [22]. This guide explores the stages of the analytical method lifecycle, compares it with alternative approaches, and provides a detailed examination of the experimental protocols and validation parameters that ensure data integrity throughout a method's operational life.

The Three-Stage Analytical Method Lifecycle

Regulatory and industry best practices have formalized the analytical method lifecycle into three defined stages, which align with process validation concepts for more efficient and reliable development [20] [21].

Stage 1: Method Design and Development

This initial stage transforms defined requirements into a working analytical procedure. The process begins with establishing an Analytical Target Profile (ATP), a prospective outline that specifies the method's performance requirements and its intended purpose [20] [21]. The ATP defines what the method needs to achieve, such as specific sensitivity (LOD, LOQ), precision, and accuracy levels, before any development work begins [19]. Method selection is then driven by marrying the "method requirement," "analyte properties," and "technique capability" to ensure final robustness [19]. For instance, Supercritical Fluid Chromatography (SFC) may be selected over Reverse-Phase Liquid Chromatography (RPLC) for chiral separations, water-sensitive analytes, or compounds with extreme hydrophobicity [19]. Development activities employ risk assessment tools and statistical experimental design (e.g., Design of Experiments) to understand method performance characteristics and establish a controlled, robust method [20].

Stage 2: Method Performance Qualification

This stage, traditionally known as validation, provides experimental confirmation that the developed analytical procedure consistently meets the criteria outlined in the ATP [20]. It confirms that the method delivers reproducible data suitable for its intended use, whether for quality control (QC), stability testing, or supporting pharmacokinetic studies [10] [1]. The activities in this phase are comprehensive, as detailed in the experimental protocols section below, and include testing for parameters such as accuracy, precision, specificity, and linearity [10] [23]. The finalization of the Analytical Control Strategy (ACS) also occurs here, defining the ongoing criteria for acceptable performance of the method during its routine use [20].

Stage 3: Continued Method Performance Verification

The lifecycle does not end with qualification. This ongoing stage provides assurance that the analytical procedure remains in a state of control during its routine use in a quality control laboratory [20] [21]. It involves continuous monitoring of system suitability and performance quality control data against pre-defined acceptance criteria [21]. Any deviations or trends are assessed through a structured change control process. This stage also encompasses any required method transfers between laboratories or sites, which must be documented and verified to ensure the method performs consistently in new environments [24] [1]. Ultimately, this phase ensures the method's reliability over many years of a product's commercial life [19].

The following diagram illustrates the interconnected nature of these three stages and their key components, including the essential feedback loops for continuous improvement.

Core Validation Parameters: The Pillars of Method Reliability

The qualification of an analytical method (Stage 2) rests on the demonstration of specific validation parameters. These parameters are the pillars that ensure the method is fit for its purpose and will generate reliable results throughout its lifecycle [10] [23].

Table 1: Key Analytical Method Validation Parameters and Their Definitions

| Validation Parameter | Definition and Purpose | Typical Acceptance Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | The degree of agreement between test results and the true value. Measures the exactness of the method [10]. | Recovery of 98–102% for drug substance, 98–102% for drug product (per ICH) [1]. |

| Precision | The degree of agreement among individual test results from multiple samplings. Measures reproducibility [10]. | RSD ≤ 2% for assay of drug substance, ≤ 3% for finished product [10] [1]. |

| Specificity/Selectivity | The ability to assess unequivocally the analyte in the presence of components that may be expected to be present (e.g., impurities, matrix) [10] [1]. | No interference observed from blank, placebo, or known impurities at the retention time of the analyte. |

| Linearity | The ability of the method to obtain test results proportional to the concentration of the analyte [10] [23]. | Correlation coefficient (r) > 0.998 [10] [1]. |

| Range | The interval between the upper and lower levels of analyte that have been demonstrated to be determined with precision, accuracy, and linearity [10]. | Typically 80-120% of the test concentration for assay [1]. |

| Limit of Detection (LOD) | The lowest concentration of an analyte that can be detected, but not necessarily quantified. Signal-to-noise ratio is typically 3:1 [10]. | Visual or statistical determination of a concentration with an S/N of 3:1. |

| Limit of Quantitation (LOQ) | The lowest concentration of an analyte that can be quantified with acceptable precision and accuracy. Signal-to-noise ratio is typically 10:1 [10]. | Visual or statistical determination of a concentration with an S/N of 10:1 and precision of ≤ 5% RSD. |

| Robustness | A measure of the method's capacity to remain unaffected by small, deliberate variations in method parameters (e.g., temperature, flow rate) [23] [22]. | The method meets system suitability criteria despite deliberate parameter fluctuations. |

Comparative Analysis: SFC vs. RPLC in Method Lifecycle Implementation

The choice of analytical technique fundamentally impacts the method's lifecycle trajectory. While Reversed-Phase Liquid Chromatography (RPLC) is the most widely employed technique, Supercritical Fluid Chromatography (SFC) offers distinct advantages for specific applications, affecting development time, robustness, and sustainability [19].

Table 2: Lifecycle Comparison of SFC and RPLC for Pharmaceutical Analysis

| Lifecycle Aspect | Supercritical Fluid Chromatography (SFC) | Reversed-Phase Liquid Chromatography (RPLC) |

|---|---|---|

| Technique Selection Driver | Optimal for chiral separations, water-labile compounds, and analytes with low or high LogP [19]. | Default technique for many molecular classes; driven by analyst familiarity and instrument availability [19]. |

| Method Development | High-throughput screening with open-access systems can significantly decrease development time [19]. | Can be complex and time-consuming, especially for analytes requiring specialized stationary phases or ion-pairing reagents [19]. |

| Analysis Time & Solvent Use | Faster separations due to low viscosity and high diffusivity of supercritical CO₂. Uses predominantly "green" CO₂ with minor organic modifier [19]. | Often longer run times. Uses large volumes of organic solvents (e.g., acetonitrile, methanol), which have environmental and cost implications [19]. |

| Validation & Transfer Success | Modern instrumentation is reliable enough to meet strict validation requirements, with successful transfers to commercial QC labs [19]. | Well-established validation protocols; widely accepted by regulators. |

| Routine Performance in QC | Proven to be very reliable in a GMP environment. At one Pfizer site, over 110 individual release runs were completed without major issues [19]. | The industry standard with predictable performance, though methods can be prone to issues like column blockage for highly lipophilic analytes [19]. |

| Representative Application | Chiral purity of Ritlecitinib; Determination of stereoisomer content in Nirmatrelvir (Paxlovid) [19]. | The most widely used technique for quality control across many small-molecule drug classes. |

Supporting Experimental Data: A direct comparison within Pfizer demonstrated the lifecycle efficiency of SFC. For an oil-based injectable drug product, a risk assessment of a potential RPLC method highlighted risks of matrix accumulation, analyte precipitation, and intensive sample preparation. In contrast, an SFC method was developed in a single day, leveraging the solubility of the API and formulation oils in the CO₂-organic mobile phase. This SFC method achieved good separation of the oil matrix and the API with simpler sample preparation, whereas the RPLC approach was projected to require several weeks of development and troubleshooting [19].

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Key Validation Parameters

To ensure the reliability of data generated throughout the method's lifecycle, specific experimental protocols are followed during the Method Performance Qualification stage (Stage 2).

Protocol for Determining Accuracy

Accuracy is typically determined by analyzing a minimum of nine determinations over a minimum of three concentration levels covering the specified range (e.g., 80%, 100%, 120% of the target concentration) [10] [1].

- Procedure: The sample matrix is spiked with a known concentration of the analyte standard. Each concentration level is analyzed in triplicate.

- Calculation: The recovery (%) for each level is calculated using the formula: (Measured Concentration / Theoretical Concentration) × 100. The mean recovery across all levels is then reported [10].

- Acceptance Criteria: For assay of a drug substance or product, recovery is typically 98–102% [1].

Protocol for Determining Precision

Precision is validated at multiple levels: repeatability, intermediate precision, and reproducibility [10] [23].

- Repeatability: Six replicate injections of a single, homogeneous sample at 100% of the test concentration. The standard deviation (SD) and relative standard deviation (%RSD) of the results are calculated [10].

- Intermediate Precision: The same procedure is repeated on a different day, by a different analyst, or using a different instrument within the same laboratory. The results from both sets are combined to calculate the overall SD and %RSD.

- Calculation: %RSD = (Standard Deviation / Mean) × 100.

- Acceptance Criteria: The Horwitz equation can provide guidance, but for assay methods, an RSD of ≤ 2% is often expected [10].

Protocol for Determining Linearity and Range

Linearity demonstrates that the analytical procedure produces results directly proportional to analyte concentration.

- Procedure: A series of standard solutions at a minimum of five concentration levels (e.g., 50%, 75%, 100%, 125%, 150% of the target concentration) is prepared and analyzed [10] [1].

- Calculation: A linear regression curve is plotted (Peak Response vs. Concentration). The correlation coefficient (r), y-intercept, and slope of the regression line are calculated. The residual sum of squares is also evaluated [10].

- Acceptance Criteria: A correlation coefficient (r) of > 0.998 is generally expected for assay methods [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

The successful execution of an analytical method throughout its lifecycle depends on a foundation of high-quality materials and reagents.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Analytical Method Development and Validation

| Item | Function and Importance in the Lifecycle |

|---|---|

| Reference Standards | Highly characterized substance of known purity and identity; essential for method development, calibration, and quantification. The quality of the standard directly impacts the accuracy of the entire method [1]. |

| Chromatographic Columns | The stationary phase is critical for achieving the required selectivity and resolution. Different chemistries (C18, chiral, HILIC, etc.) are selected based on the analyte's properties defined in the ATP [19]. |

| HPLC/SFC Grade Solvents | High-purity mobile phase components are necessary to maintain system health and prevent baseline noise, ghost peaks, and method variability that can compromise data in routine use [19]. |

| Sample Preparation Solvents & Reagents | Solvents for extraction, dilution, or derivatization must be compatible with both the sample matrix and the analytical technique to ensure accurate analyte recovery and stability [19] [1]. |

| System Suitability Standards | A prepared mixture used to verify that the chromatographic system is adequate for the intended analysis. It is a critical checkpoint before every analytical run in routine QC (Stage 3) [21]. |

The journey of an analytical method from development to routine use is not a one-time event but a dynamic, managed lifecycle. Adopting the structured, three-stage framework of Procedure Design, Performance Qualification, and Continued Verification ensures methods are robust, reliable, and compliant with evolving regulatory standards like ICH Q14 and USP <1220> [20] [21]. This holistic view, supported by rigorous validation protocols and a clear Analytical Target Profile, minimizes the resource burden of downstream redevelopment and troubleshooting [19]. As the industry continues to advance, the integration of Quality by Design (QbD) principles and lifecycle management will be paramount for pharmaceutical developers and researchers to ensure the consistent delivery of high-quality, safe, and effective medicines to patients.

From Theory to Practice: Implementing and Applying Key Validation Parameters

Experimental Designs for Assessing Specificity and Selectivity in Complex Matrices

The analysis of target compounds in complex matrices such as biological fluids, environmental samples, and food products presents significant analytical challenges due to the presence of numerous interfering substances that can compromise method reliability. Within method validation, specificity and selectivity are critical parameters that determine an analytical procedure's ability to accurately measure the analyte amidst these potential interferents [10]. While often used interchangeably, a distinction can be made where specificity refers to the method's ability to assess the analyte unequivocally in the presence of expected components, whereas selectivity describes its ability to differentiate the analyte from other analytes in the mixture [25] [10]. This guide objectively compares contemporary experimental designs for evaluating these parameters, focusing on mass spectrometry-based techniques that have become the cornerstone for high-quality quantitative analysis in complex matrices [26] [27].

Fundamental Concepts and Validation Parameters

According to international validation guidelines, the selectivity of an analytical method is defined as its ability to measure accurately an analyte in the presence of interferences that may be expected to be present in the sample matrix [10]. This is typically checked by examining chromatographic blanks in the expected time window of the analyte peak to confirm the absence of co-eluting signals [10]. Method validation requires testing multiple attributes to ensure the procedure provides useful and valid data, with specificity/selectivity being foremost among other parameters including accuracy, precision, linearity, and limits of detection and quantification [10].

The fundamental challenge in analyzing complex matrices is the matrix effect (ME), defined as the combined effects of all sample components other than the analyte on the measurement [27]. In mass spectrometry, these effects occur when interference species alter ionization efficiency in the source when co-eluting with the target analyte, causing either ion suppression or enhancement [27]. The extent of ME is variable and unpredictable—the same analyte can show different MS responses in different matrices, and the same matrix can affect different analytes differently [27].

Comparative Experimental Designs and Methodologies

Multiple Reaction Monitoring (MRM) and MRM³

Traditional MRM (MRM²) on triple quadrupole mass spectrometers has become the technique of choice for highly sensitive and selective quantification in biological matrices [26]. This approach provides two stages of mass filtering: selection of a precursor ion in the first quadrupole (Q1) and selection of a characteristic product ion after fragmentation in the second quadrupole (Q2) [26]. While this typically provides sufficient selectivity, detection can still be impacted by high background or interferences from the matrix that share the same transition [26].

MRM³ quantification represents an advanced workflow available on QTRAP systems that adds a third dimension of selectivity [26]. In this approach, the analyte ion is first selected in Q1, fragmented in the Q2 collision cell, then a specific product ion is isolated and fragmented again in the linear ion trap (LIT), with second-generation product ions scanned out to the detector [26]. This additional fragmentation step provides superior selectivity by eliminating interferences that might co-elute and share identical precursor and first-generation product ions with the analyte.

Table 1: Comparison of MRM² and MRM³ Performance Characteristics

| Parameter | Traditional MRM (MRM²) | MRM³ Quantification |

|---|---|---|

| Selectivity Principle | Two stages of mass selection (Q1, Q3) | Three stages of mass selection (Q1, LIT isolation, LIT fragmentation) |

| Interference Removal | Effective for most applications | Complete removal of tough interferences with same MRM transition and retention time |

| Sensitivity Impact | High sensitivity for most analytes | Potential for up to 100x higher sensitivity in LIT mode with Linear Accelerator technology |

| Best Applications | Routine analysis of low-complexity samples | Complex matrices with high background, difficult separations, simplified sample preparation |

| Limitations | Susceptible to interferences with identical transitions | Requires specialized instrumentation (QTRAP systems), slightly slower cycle times |

Experimental Protocol for MRM³ Method Development

- System Configuration: Utilize a QTRAP system with hybrid triple quadrupole linear ion trap configuration.

- Initial MS/MS Optimization: Infuse pure analyte standard to determine optimal precursor ion and most abundant product ions using traditional MRM.

- Ion Trap Parameter Optimization: For the most abundant product ion from step 2, optimize trap collision energy and excitation time for generation of second-generation product ions.

- MRM³ Method Setup: Configure the method with:

- Q1 selection at unit resolution (0.7 Th FWHM)

- Q2 collision energy optimized for first fragmentation

- LIT isolation of selected product ion

- Application of single frequency/narrow band excitation for second fragmentation

- Mass scan of second-generation product ions

- Chromatographic Optimization: Employ appropriate LC separation to minimize matrix components entering the MS simultaneously with the analyte.

- Validation: Compare method performance against traditional MRM using spiked matrix samples to quantify improvement in selectivity and reduction of background interference.

The following workflow diagram illustrates the fundamental operational principles of MRM² versus MRM³:

High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry (HRMS) and Chromatographic Solutions

As an alternative to MRM³ approaches, high-resolution mass spectrometry provides another dimension of selectivity through accurate mass measurements [28]. When compounds have identical or very close m/z values, HRMS can resolve minimal mass differences that triple quadrupole instruments cannot distinguish [28]. This approach is particularly valuable for non-targeted analysis and when analyzing compounds with similar fragmentation patterns.

Chromatographic optimization remains a fundamental strategy for improving selectivity [29]. Recent advances include:

- Multidimensional chromatography: Comprehensive two-dimensional LC (LC×LC) for increased peak capacity

- Advanced stationary phases: Novel chemistries providing alternative separation mechanisms

- On-line enrichment methodologies: Solid-phase microextraction (SPME) and other concentration techniques that also clean up samples [29]

Table 2: Comparison of Selectivity-Enhancement Techniques for Complex Matrices

| Technique | Mechanism of Selectivity | Best for Analyzing | Complexity/Cost | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional MRM | Two mass filtering stages | Most small molecules in moderate matrix | Moderate | Interferences with same transition |

| MRM³ | Three mass filtering stages | Small molecules, peptides, protein biomarkers | High | Requires specific instrumentation |

| High-Resolution MS | Accurate mass measurement | Non-targeted analysis, unknown compounds | High | Lower sensitivity than triple quad |

| Multidimensional LC | Orthogonal separation mechanisms | Highly complex samples (e.g., proteomics) | High | Method development complexity |

| Advanced SPME Fibers | Selective extraction/enrichment | Trace analysis in environmental/biological samples | Moderate | Fiber lifetime, carryover potential |

Experimental Protocols for Assessing Matrix Effects

Post-Column Infusion Method

The post-column infusion method, initially proposed by Bonfiglio et al., provides a qualitative assessment of matrix effects throughout the chromatographic run [27].

Protocol:

- Prepare a blank sample extract using the intended sample preparation procedure.

- Inject the blank extract onto the LC column while maintaining a constant mobile phase flow.

- Using a T-piece, introduce a constant flow of analyte standard post-column (after separation but before MS ionization).

- Monitor the analyte signal throughout the chromatographic run.

- Identify regions of ion suppression or enhancement as decreases or increases in the steady analyte signal.

Data Interpretation: Signal suppression appears as negative peaks (dips) in the chromatogram, indicating regions where matrix components co-elute and suppress ionization of the analyte. This method is particularly valuable during method development to identify optimal chromatographic conditions and retention times that minimize matrix effects [27].

Post-Extraction Spike Method

The post-extraction spike method, developed by Matuszewski et al., provides quantitative assessment of matrix effects [27].

Protocol:

- Prepare blank matrix samples from at least six different sources.

- Process these blanks through the entire sample preparation procedure.

- Spike the analyte at known concentrations into the processed blank extracts (post-extraction).

- Prepare equivalent concentration standards in pure solvent.

- Analyze both sets and compare the responses.

Calculation: Matrix Effect (ME) = (Peak area of post-spiked sample) / (Peak area of standard solution) × 100%

An ME of 100% indicates no matrix effect, <100% indicates suppression, and >100% indicates enhancement. This method is particularly valuable for evaluating lot-to-lot variability of matrix effects [27].

Slope Ratio Analysis

The slope ratio analysis method, a modification by Romero-Gonzáles and Sulyok, extends the post-extraction spike approach across a concentration range [27].

Protocol:

- Prepare matrix-matched calibration standards at multiple concentration levels using blank matrix from at least six different sources.

- Prepare solvent-based calibration standards at identical concentrations.

- Analyze both sets and construct calibration curves.

- Compare the slopes of the matrix-matched versus solvent-based calibration curves.

Calculation: Matrix Effect = (Slope of matrix-matched calibration) / (Slope of solvent calibration) × 100%

This approach provides a more comprehensive assessment of matrix effects across the analytical range rather than at a single concentration level [27].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Specificity/Selectivity Experiments

| Reagent/Material | Function in Experimental Design | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Internal Standards | Compensates for matrix effects and extraction variability; ideal for quantitative accuracy | Bioanalytical method development, pharmacokinetic studies |

| Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs) | Provides highly selective extraction; mimics antibody-antigen recognition | Selective extraction of target analytes from complex matrices |

| Phospholipid Removal Plates | Selectively removes phospholipids (major source of matrix effects in biological samples) | Plasma/serum analysis to reduce ionization suppression |

| Diversified Blank Matrices | Assess matrix effects across different sources; essential for method validation | All bioanalytical methods (use at least 6 different lots) |

| Hybrid Triple Quadrupole-LIT Systems | Enables MRM³ capability for ultimate selectivity in challenging applications | Metabolomics, biomarker verification, complex impurity detection |

| Appropriate Surrogate Matrices | Alternative to scarce or expensive biological matrices; demonstrates similar MS response | Analysis of endogenous compounds where true blank matrix unavailable |

The selection of an appropriate experimental design for assessing specificity and selectivity must be guided by the particular analytical challenge, matrix complexity, and required sensitivity. For most routine applications, traditional MRM provides an excellent balance of performance and practicality. When facing persistent interferences that compromise data quality, MRM³ offers a powerful solution with superior selectivity, though it requires specialized instrumentation. For comprehensive method validation, a combination of post-column infusion (for qualitative assessment of problematic chromatographic regions) and post-extraction spike methods (for quantitative determination of matrix effects) provides the most complete picture of method performance. The fundamental principle remains that early and thorough evaluation of specificity and selectivity during method development prevents analytical failures during routine application, ultimately generating the dependable data required for critical decision-making in pharmaceutical, clinical, and environmental applications.

Protocols for Determining Accuracy (through Spiking/Recovery) and Precision (Repeatability, Intermediate Precision)

In pharmaceutical analysis and bioanalytical research, validating a method is crucial to confirm that it is suitable for its intended purpose, ensuring the reliability and consistency of results [30]. Accuracy and precision are two fundamental validation parameters that measure different aspects of this reliability. Accuracy refers to the closeness of agreement between a measured value and a true or accepted reference value [31] [32]. It is often assessed through spike-and-recovery experiments, which determine if a sample matrix affects the detection of an analyte compared to a standard diluent [33] [34]. Precision, on the other hand, expresses the closeness of agreement between a series of measurements obtained from multiple sampling of the same homogeneous sample under specified conditions [35] [31]. It is typically subdivided into repeatability (short-term, same-operator precision) and intermediate precision (longer-term, within-laboratory variations) [35] [36]. This guide objectively compares the performance of different methodological approaches for assessing these critical parameters, providing detailed protocols and representative data to support robust analytical practices.

Determining Accuracy through Spike-and-Recovery Experiments

Core Principles and Purpose

The spike-and-recovery experiment is designed to validate the accuracy of an assay, such as an ELISA, by quantifying the potential matrix effects of a biological sample [33] [34]. The fundamental question it answers is whether the sample matrix (e.g., serum, urine, culture supernatant) yields the same recovery of a known analyte as the standard diluent used for the calibration curve. When an analyte is spiked into a natural sample matrix, components of that matrix can sometimes interfere with antibody-analyte binding, leading to either an enhanced or diminished signal compared to the pure standard. A successful spike-and-recovery test confirms that the matrix does not interfere, thereby justifying the use of the standard curve for calculating analyte concentrations in unknown samples [33].

Detailed Experimental Protocol

The following protocol, adapted from established methodologies, outlines the key steps for performing a spike-and-recovery assessment [33] [34]:

- Preparation of Spiked Samples: A known quantity of the purified analyte (the "spike") is added to the natural sample matrix. The concentration of the spike should be within the quantitative range of the assay.

- Preparation of Control: An identical quantity of the analyte is spiked into the standard diluent (the matrix used to prepare the standard curve). This serves as the control, representing 100% ideal recovery.

- Assay Execution: Both the spiked sample matrix and the spiked standard diluent are analyzed using the assay (e.g., ELISA), and their responses are measured.

- Data Calculation: The percentage recovery is calculated using the formula:

- % Recovery = (Observed Concentration in Spiked Sample / Observed Concentration in Spiked Diluent) × 100%

- The observed concentration for the spiked sample matrix should ideally be corrected by subtracting the endogenous level of the analyte measured in an unspiked aliquot of the same sample [33].

Performance Data and Acceptance Criteria

The table below summarizes typical spike-and-recovery results for a recombinant human IL-1 beta ELISA in human urine samples, demonstrating the calculation of percent recovery [33].

Table 1: Representative ELISA Spike-and-Recovery Data for Recombinant Human IL-1 Beta in Human Urine

| Sample (n) | Spike Level | Expected Concentration (pg/mL) | Observed Concentration (Mean, pg/mL) | Recovery % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diluent Control | Low (15 pg/mL) | 17.0 | 17.0 | 100.0 |

| Urine (9) | Low (15 pg/mL) | 17.0 | 14.7 | 86.3 |

| Diluent Control | Medium (40 pg/mL) | 44.1 | 44.1 | 100.0 |

| Urine (9) | Medium (40 pg/mL) | 44.1 | 37.8 | 85.8 |

| Diluent Control | High (80 pg/mL) | 81.6 | 81.6 | 100.0 |

| Urine (9) | High (80 pg/mL) | 81.6 | 69.0 | 84.6 |

The acceptance criteria for recovery are context-dependent but a common benchmark in immunoassays is a recovery of 80–120% [34]. Results outside this range indicate significant matrix interference. In the example above, the consistent ~85-86% recovery across spike levels suggests a constant matrix effect, which may be correctable by modifying the sample diluent [33]. The following workflow diagram summarizes the spike-and-recovery process and troubleshooting paths.

Determining Precision: Repeatability and Intermediate Precision

Core Principles and Definitions

Precision measures the random error or the scatter of results under specified conditions [37] [31]. It is hierarchically evaluated at different levels: