Strategic Wavelength Selection in UV-Vis Spectroscopy: A Complete Guide for Pharmaceutical Analysis

This article provides a comprehensive framework for selecting and validating analytical wavelengths in UV-Vis spectroscopy, tailored specifically for researchers and drug development professionals.

Strategic Wavelength Selection in UV-Vis Spectroscopy: A Complete Guide for Pharmaceutical Analysis

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for selecting and validating analytical wavelengths in UV-Vis spectroscopy, tailored specifically for researchers and drug development professionals. Covering foundational principles through advanced applications, it details how to identify optimal wavelengths using spectral analysis, leverage chemometric methods for complex mixtures, troubleshoot environmental interferences, and rigorously validate methods according to ICH guidelines. The content synthesizes current methodologies with emerging trends, offering practical strategies to enhance accuracy, specificity, and regulatory compliance in pharmaceutical quantification.

Understanding UV-Vis Fundamentals: Principles of Light-Matter Interaction and Spectral Analysis

Core Principles of UV-Vis Spectroscopy and Electronic Transitions

Ultraviolet-Visible (UV-Vis) spectroscopy is a fundamental analytical technique based on the absorption of light in the ultraviolet and visible regions of the electromagnetic spectrum. This technique is indispensable across chemistry, pharmacy, and environmental science for identifying molecules and determining their concentrations [1]. The core principle revolves around the interaction between light and matter, specifically the excitation of electrons to higher energy states upon absorbing specific wavelengths of light [2]. Within the context of a broader thesis on selecting wavelengths for analyte quantification, understanding these electronic transitions and the factors that influence the absorption spectrum is paramount for developing accurate, sensitive, and reliable analytical methods.

Theoretical Foundation and Electronic Transitions

The Beer-Lambert Law

The quantitative foundation of UV-Vis spectroscopy is the Beer-Lambert law. It states that the absorbance (A) of light by a solution is directly proportional to the concentration (c) of the absorbing species and the path length (L) of the light through the solution [2] [3]. The law is expressed as:

A = ɛcL

Here, ɛ is the molar absorptivity (or extinction coefficient), a substance-specific constant that indicates how strongly a chemical species absorbs light at a particular wavelength [2] [3]. Absorbance is a dimensionless quantity defined as A = log₁₀(I₀/I), where I₀ is the intensity of the incident light and I is the intensity of the transmitted light [3]. For accurate quantification, it is critical that absorbance values remain within the instrument's dynamic range, typically below 1, to ensure a linear relationship with concentration [3].

Electronic Transitions in Molecules

Absorption of UV or visible light promotes outer electrons from their ground state to a higher energy, excited state. This process is known as an electronic transition [2]. The energy of the absorbed photon (E) must exactly match the energy difference (ΔE) between the two electronic states, which is inversely proportional to its wavelength (λ) [3]. The types of electronic transitions available depend on the molecular structure of the analyte.

The following table summarizes the primary electronic transitions involved in UV-Vis spectroscopy:

Table: Types of Electronic Transitions in UV-Vis Spectroscopy

| Transition Type | Description | Typical Wavelength Range | Molar Absorptivity (ɛ) [L·mol⁻¹·cm⁻¹] | Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| σ → σ* | Electron in a bonding σ orbital jumps to an antibonding σ* orbital. | < 200 nm (High energy) | - | Methane (λmax = 125 nm) [2] |

| n → σ* | Excitation of a non-bonding (lone pair) electron to a σ* orbital. | 150 - 250 nm | Low | Saturated compounds with heteroatoms (e.g., O, N) [2] |

| π → π* | Electron in a bonding π orbital jumps to an antibonding π* orbital. | 200 - 700 nm | High (1,000 - 10,000) | Ethene (λmax = 165 nm), conjugated systems (e.g., 1,3-butadiene, λmax = 217 nm) [2] [4] |

| n → π* | Excitation of a non-bonding electron to a π* orbital. | 200 - 700 nm | Low (10 - 100) | Carbonyl compounds (e.g., acetone) [2] [4] |

| Charge-Transfer | Electron transfers from a donor to an acceptor moiety within a complex. | Varies | Very High (> 10,000) | Many inorganic complexes [2] |

For organic molecules, the most relevant transitions are the π → π* and n → π* transitions, as they fall within the readily measurable range of standard UV-Vis spectrophotometers (200 - 700 nm) [2]. Molecules containing conjugated π-systems, where single and double bonds alternate, are particularly important. As the conjugation length increases, the energy required for a π → π* transition decreases, causing the absorption to shift to longer wavelengths (a phenomenon known as a bathochromic or red shift) [4]. A classic example is beta-carotene, which has 11 conjugated double bonds and absorbs blue light, making carrots appear orange [4].

The Chromophore Concept

A chromophore is the functional group in a molecule responsible for absorbing UV or visible light. These groups contain valence electrons of low excitation energy, typically involving π electrons or non-bonding electrons [2] [1]. Common chromophores include carbonyl groups (C=O), alkenes (C=C), aromatic rings, and azo groups (-N=N-). The structure of the chromophore and its molecular environment dictate the specific wavelength and intensity of absorption.

Instrumentation and Workflow

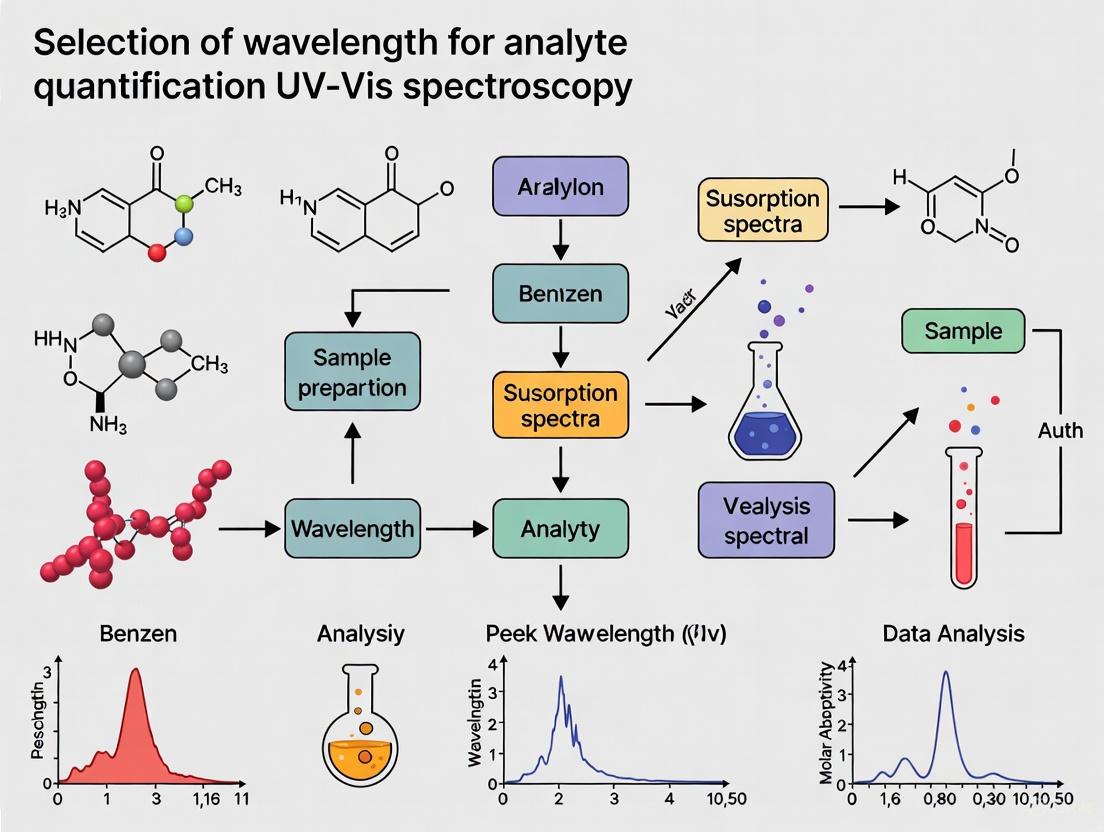

A UV-Vis spectrophotometer is designed to measure the absorption of light by a sample across a range of wavelengths. The following workflow diagram illustrates the key components and process flow within a typical instrument.

Diagram: UV-Vis Spectrophotometer Workflow and Key Components.

Key Instrument Components

- Light Source: Provides broad-wavelength radiation. Instruments often use a combination of a deuterium lamp for UV light and a tungsten or halogen lamp for visible light [3] [1].

- Wavelength Selector (Monochromator): Isolates a narrow band of wavelengths from the broad-spectrum light source. This typically involves a diffraction grating, which can be rotated to select specific wavelengths. A higher groove density (e.g., >1200 grooves/mm) provides better optical resolution [3].

- Sample Container: Holds the sample, typically a cuvette. For UV light, quartz cuvettes are essential as they are transparent to UV light, unlike glass or plastic [3].

- Detector: Converts the intensity of transmitted light into an electrical signal. Common detectors include photomultiplier tubes (PMTs), which are highly sensitive for detecting low light levels, and photodiodes [3].

- Processor and Software: Processes the signals from the detector, compares the sample and reference beam intensities, and generates the absorption spectrum [1].

Experimental Protocol for Analyte Quantification

This section provides a detailed methodology for using UV-Vis spectroscopy to quantify the concentration of an analyte in solution, a common application in drug development and research.

Preparation of Reagents and Standards

- Solvent: Select a high-purity solvent that does not absorb significantly in the spectral region of interest. Common choices include water, methanol, and acetonitrile. The solvent must be the same for all standards and the unknown sample [3].

- Stock Standard Solution: Accurately weigh the pure analyte and dissolve it in the solvent to prepare a stock solution of known, relatively high concentration.

- Standard Solutions: Dilute the stock solution serially to prepare a set of at least 5-6 standard solutions covering a range of concentrations. The concentrations should bracket the expected concentration of the unknown sample.

- Blank Solution: The blank is the pure solvent, used to zero the instrument and account for any absorption from the cuvette or solvent [3].

- Unknown Sample Solution: Prepare the sample of unknown concentration in the same solvent.

Spectral Acquisition and Wavelength Selection

- Instrument Warm-up and Initialization: Turn on the spectrophotometer and allow the lamps to stabilize for the time recommended by the manufacturer (typically 15-30 minutes).

- Blank Measurement: Place the blank solution (solvent) in a clean cuvette and insert it into the sample compartment. Execute an "auto-zero" or "baseline correction" command. This sets the 0% absorbance (or 100% transmittance) baseline for the instrument [3].

- Initial Scan: Using a representative standard solution or the unknown sample, perform a broad-wavelength scan (e.g., from 200 nm to 700 nm) to obtain the full absorption spectrum.

- Identify λmax: Examine the spectrum to identify the wavelength of maximum absorption (λmax) for the analyte. This is the optimal wavelength for quantification as it provides the greatest sensitivity and minimizes the effect of minor instrumental wavelength drift [1].

Quantification via Calibration Curve

- Set Measurement Wavelength: Set the spectrophotometer to the fixed wavelength (λmax) identified in the previous step.

- Measure Standards: Measure the absorbance of each standard solution in sequence, ensuring the cuvette is clean and properly positioned each time.

- Plot Calibration Curve: Construct a graph plotting the measured absorbance (y-axis) against the known concentration of each standard (x-axis).

- Linear Regression Analysis: Perform a linear regression analysis on the data points. The Beer-Lambert law predicts a straight line passing through the origin (A = ɛL * c). The correlation coefficient (R²) should be >0.995 for a high-quality calibration.

- Determine Unknown Concentration: Measure the absorbance of the unknown sample solution at the same λmax. Use the equation of the calibration curve to calculate the concentration of the unknown.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details key materials and reagents essential for conducting UV-Vis experiments, particularly for quantification in research and drug development.

Table: Essential Materials for UV-Vis Spectroscopy Experiments

| Item | Function/Description | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Spectrophotometer | Instrument that measures light absorption. | Choose between single-beam (measures sample and blank sequentially) or double-beam (measures sample and blank simultaneously for higher stability) [1]. |

| Quartz Cuvettes | Containers for holding liquid samples during measurement. | Required for UV range (<330 nm) due to UV transparency. Have a defined pathlength (usually 1 cm) which is critical for the Beer-Lambert law [3]. |

| High-Purity Solvents | Medium for dissolving the analyte. | Must be spectroscopically pure (e.g., "HPLC grade" or "UV-spectroscopy grade") to ensure low background absorption [3]. |

| Analytical Balance | For precise weighing of solid analytes to prepare standard solutions. | Accuracy to 0.1 mg is typically required for preparing quantitative standard solutions. |

| Volumetric Glassware | (Flasks, pipettes) For accurate preparation and dilution of standard and sample solutions. | Class A glassware ensures the highest accuracy and precision for quantitative work. |

| Reference Standard | A highly purified form of the analyte with a known and certified composition. | Essential for creating an accurate calibration curve for quantification. |

Critical Considerations for Wavelength Selection in Quantification

Framed within the broader thesis of selecting wavelengths for analyte quantification, several factors beyond simply choosing λmax must be considered to ensure method robustness.

- Sensitivity and Specificity at λmax: The wavelength of maximum absorption (λmax) provides the highest sensitivity because the molar absorptivity (ɛ) is greatest. This allows for the detection of lower concentrations of the analyte. Furthermore, measuring at a peak maximum is often more specific and less susceptible to errors from small, unintentional shifts in the instrument's wavelength calibration [1].

- Solvent Effects: The solvent can cause shifts in the absorption spectrum. Peaks resulting from n → π* transitions are often shifted to shorter wavelengths (a blue shift) with increasing solvent polarity. Conversely, π → π* transitions may experience a small shift to longer wavelengths (a red shift) in polar solvents [2]. Therefore, the calibration and sample analysis must be performed in the same solvent.

- Spectral Interferences: In complex mixtures, other components (impurities, excipients, or buffers) may absorb at the λmax of the target analyte. In such cases, it may be necessary to select an alternative wavelength where the analyte still has significant absorption but the interference is minimized. This trade-off between sensitivity and selectivity is a key decision in method development.

- Instrument Capabilities: Verify that the selected wavelength is within the operational range of the instrument's light source and detector. For example, measurements below 200 nm require purging the optical path with nitrogen to remove oxygen, which absorbs in that deep-UV region [3].

The accuracy of analyte quantification in Ultraviolet-Visible (UV-Vis) spectroscopy is fundamentally governed by the precise selection of wavelength, which is directly influenced by the performance of three core instrumentation components: the light source, monochromator, and detector. The reliability of data used in critical areas such as drug development and quality control hinges on a robust understanding of the operating principles, capabilities, and limitations of these components. This guide provides an in-depth technical examination of these subsystems, detailing their function in ensuring the integrity of spectroscopic measurements for research and regulatory applications.

Core Components of a UV-Vis Spectrophotometer

A UV-Vis spectrophotometer operates on the principle of measuring the absorption of light by a sample. The instrumental pathway of light, from emission to detection, is orchestrated by several key components, as illustrated in the workflow below.

The light source must provide stable and sufficient energy across the entire UV and visible wavelength range. Most instruments use multiple lamps to achieve this, as no single lamp is optimal for all wavelengths [3].

Deuterium Lamps: These are the standard source for the UV region (approximately 190–400 nm). They generate a continuous spectrum through the excitation of deuterium gas and are prized for their high intensity and stability in this critical range [5] [3].

Tungsten-Halogen Lamps: This type of lamp is the workhorse for the visible region (approximately 350–800 nm). The halogen cycle ensures a long lamp life and consistent output of white light [1] [3].

Xenon Flash Lamps: These lamps generate light by discharging a capacitor through a xenon gas-filled tube. Their key advantage is speed; they flash thousands of times per second, enabling rapid spectrum capture without the need for mechanical scanning. This makes them ideal for spectrometer-based instruments [6] [1]. A single xenon lamp can cover both UV and visible ranges, but they can be more expensive and less stable than the deuterium/tungsten-halogen combination [3].

Table 1: Comparison of Common UV-Vis Light Sources

| Lamp Type | Spectral Range | Key Characteristics | Primary Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Deuterium | ~190–400 nm | High intensity in UV, stable | UV region measurements |

| Tungsten-Halogen | ~350–2500 nm | Continuous visible spectrum, long life | Visible region measurements |

| Xenon Flash | ~190–800 nm | Broadband, pulsed light, fast | Rapid scanning & spectrometers |

Monochromators

The monochromator is the wavelength selector of the instrument. Its function is to take the broad-spectrum light from the source and isolate a narrow, nearly monochromatic beam. This is critical because the Beer-Lambert law, which relates absorbance to concentration, is defined for a single wavelength [5].

The most common optical arrangement is the Czerny-Turner configuration [6]. Key components include:

- Entrance Slit: Controls the amount of light entering and reduces stray light.

- Collimating Mirror: Makes the light rays parallel.

- Diffraction Grating: This is the heart of the monochromator. It is a surface with many closely spaced parallel grooves that disperse the light into its component wavelengths. Rotating the grating changes the wavelength that passes through the exit slit [5] [6].

- Exit Slit: Further narrows the band of wavelengths that finally illuminates the sample.

The quality of a monochromator is often defined by its spectral bandwidth (the narrowness of the selected wavelength band, typically 5–8 nm for a standard UV-Vis detector [5]) and its resolution, which is influenced by the number of grooves per mm on the grating. A higher groove frequency (e.g., 1200 grooves/mm or more) provides better resolution [3].

Monochromators vs. Spectrometers: It is crucial to distinguish between these two. A monochromator selects a single wavelength (or a narrow band) to pass through the sample at a time. In contrast, a spectrometer, often using a diode array, disperses the entire light spectrum after it has passed through the sample, allowing all wavelengths to be detected simultaneously [6]. This fundamental difference dictates the instrument's speed and application suitability.

Detectors

Detectors convert the transmitted light intensity into an electrical signal proportional to the light's power. The choice of detector impacts the sensitivity, dynamic range, and signal-to-noise ratio of the measurement.

Table 2: Key Detector Types in UV-Vis Spectroscopy

| Detector Type | Operating Principle | Sensitivity & Speed | Key Advantages & Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Photomultiplier Tube (PMT) | Photoelectric effect followed by electron multiplication via dynodes [3] [7] | Very high sensitivity, fast response [3] [7] | Adv: Excellent for low-light levels, high gain [7]. Lim: Can be damaged by high-intensity light [7]. |

| Photodiode Array (PDA) | Array of silicon photodiodes; measures all wavelengths simultaneously [5] [7] | Less sensitive than PMT, but very fast [7] | Adv: Rugged, no moving parts, enables instant spectral capture and peak purity analysis [5] [7]. |

| Charge-Coupled Device (CCD) | Array of photo-capacitors (pixels) storing charge proportional to light intensity [7] | Extremely high sensitivity, low noise [7] | Adv: Ideal for very low-intensity signals (e.g., fluorescence) [7]. |

The relationship between the components and the final absorbance output is governed by the Beer-Lambert law, as shown in the signal processing pathway below.

Experimental Protocols for Wavelength Selection & Validation

The selection of an optimal analytical wavelength is not arbitrary; it is a systematic process to ensure maximum sensitivity, specificity, and linearity for quantification.

Protocol: Determination of λmax for Analyte Quantification

This protocol is used to identify the wavelength of maximum absorbance (λmax) for a target analyte, which is typically the preferred wavelength for quantification due to higher sensitivity and reduced error from minor instrument wavelength drift [1].

Instrument Preparation:

- Power on the spectrophotometer and allow the lamp(s) to warm up for the time specified by the manufacturer (typically 15-30 minutes).

- Select the spectrum acquisition mode on the instrument's software.

Blank Measurement:

- Fill a quartz cuvette (for UV work below ~350 nm) or high-quality optical glass cuvette (for visible work) with the solvent used to prepare the sample.

- Place the cuvette in the sample holder and run a baseline correction or blank measurement. This records the baseline intensity of the light source and solvent (I₀).

Sample Scanning:

- Prepare a standard solution of the analyte at a concentration that will yield an absorbance between 0.5 and 1.0 AU for a reliable signal-to-noise ratio.

- Replace the blank cuvette with the sample cuvette.

- Acquire an absorption spectrum over an appropriate range (e.g., 200–800 nm). The instrument will scan through the wavelengths and record the absorbance at each point.

Data Analysis and λmax Selection:

- Examine the resulting absorption spectrum. The wavelength corresponding to the highest peak of interest is the λmax. This wavelength should be used for subsequent quantitative measurements.

Protocol: Peak Purity Assessment using a Photodiode Array (PDA) Detector

A key advantage of a PDA detector is its ability to assess peak purity during chromatographic separation, which is critical for verifying that a single analyte is being quantified without interference [5].

HPLC-PDA Setup:

- Utilize an HPLC system equipped with a photodiode array detector. The method should be developed to separate the analyte of interest from potential impurities.

Spectral Acquisition:

- As the chromatographic peak elutes from the column and passes through the flow cell, the PDA detector continuously captures full UV-Vis spectra (e.g., from 190–400 nm) at multiple points across the peak (e.g., upslope, apex, downslope).

Spectral Overlay and Comparison:

- The instrument's software overlays the spectra collected from different parts of the peak.

- The operator then compares these spectra. A pure peak will show spectrally homogeneous profiles, meaning all overlaid spectra are identical.

Purity Index Calculation:

- The software calculates a numerical peak purity index or purity angle by comparing the spectra. A purity index close to 1.000 (or a purity angle below a specified threshold) indicates a spectrally pure peak, confirming that the quantification is likely free from co-eluting impurities [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Materials for UV-Vis Spectrophotometric Analysis

| Item | Function & Importance |

|---|---|

| Quartz Cuvettes | Standard sample holders for UV-Vis range. Quartz is transparent down to ~190 nm, unlike glass or plastic, which absorb UV light [3]. |

| Deuterium & Tungsten-Halogen Lamps | Standardized light sources requiring periodic replacement. Their stability is critical for quantitative accuracy [5] [3]. |

| High-Purity Solvents | (e.g., HPLC-grade water, acetonitrile, methanol). Used to dissolve samples and prepare mobile phases. Impurities can absorb light and lead to inaccurate baseline and absorbance readings. |

| Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) | High-purity analytes with well-characterized properties and known molar absorptivity (ε). Essential for calibrating the instrument, validating methods, and creating calibration curves [5]. |

| Buffer Salts & Chemicals | Used to maintain a constant pH in the sample solution, which is vital as the UV absorption spectrum of many compounds (e.g., proteins, nucleic acids) can be highly pH-dependent. |

The journey from a light photon to a quantitative data point is a carefully engineered process. The synergistic operation of stable light sources, high-resolution monochromators, and sensitive detectors forms the foundation of reliable UV-Vis spectroscopy. For the researcher focused on analyte quantification, a deep technical understanding of these components—from the groove density of a diffraction grating to the multi-channel advantage of a PDA—is not merely academic. It is a practical necessity for making informed decisions during method development, troubleshooting analytical problems, and ultimately, generating data that meets the rigorous demands of scientific research and regulatory compliance.

The Beer-Lambert Law (BLL), also referred to as the Beer-Lambert-Bouguer Law, is an empirical relationship that forms the cornerstone of quantitative optical spectroscopy. It describes the attenuation of light as it passes through a medium, establishing a direct and linear relationship between the absorbance of light and the properties of that medium—specifically, the concentration of the absorbing species and the path length the light travels. This law is indispensable in modern analytical chemistry, biochemistry, and pharmaceutical sciences for determining the concentration of analytes in solution. Its development spans nearly two centuries, beginning with the work of Pierre Bouguer in 1729, who first discovered that light intensity decreases exponentially with the path length traveled through a medium. Johann Heinrich Lambert later formalized this mathematical relationship in his 1760 publication, Photometria. It was August Beer, however, who in 1852 extended the concept by demonstrating that absorbance is directly proportional to the concentration of the solution, thereby completing the formulation of the law as it is known today [8] [9].

The enduring utility of the Beer-Lambert Law lies in its ability to provide a simple, quantitative basis for analyzing spectroscopic data. For researchers in drug development, it enables the precise quantification of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs), the monitoring of reaction kinetics, and the assessment of nucleic acid or protein purity. When applied to UV-Vis research, the selection of an appropriate analytical wavelength is paramount, as the law's validity hinges on measurements taken at a wavelength where the analyte exhibits significant and characteristic absorption [3] [10].

Mathematical Foundation and Theoretical Principles

The Beer-Lambert Law can be expressed through several equivalent formulations, with the most common form relating absorbance to the properties of the absorbing medium.

Core Equation and Components

The standard form of the law is: A = ε · l · c Where:

- A is the Absorbance (also known as optical density), a dimensionless quantity [11] [10].

- ε is the Molar Absorptivity (or molar extinction coefficient), with units typically of L·mol⁻¹·cm⁻¹. This is a substance-specific constant at a given wavelength, representing how strongly a chemical species absorbs light at that wavelength [11] [12].

- l is the Path Length, representing the distance (in cm) light travels through the solution, typically standardized to 1 cm in cuvette-based measurements [13] [11].

- c is the Concentration of the absorbing species in the solution, with units of mol·L⁻¹ (M) [13] [11].

The law is also intrinsically related to the intensity of incident and transmitted light. Absorbance is defined logarithmically as: A = log₁₀(I₀/I) In this equation, I₀ is the intensity of the incident light, and I is the intensity of the transmitted light [11] [10]. The ratio I/I₀ defines the Transmittance (T), which can be expressed as a percentage [10]. The relationship between absorbance and transmittance is: A = -log₁₀(T)

The following table outlines the practical relationship between absorbance and transmittance, which is crucial for interpreting spectrometer readings [10]:

Table 1: Relationship Between Absorbance and Transmittance

| Absorbance (A) | Transmittance (T) | Percent Transmittance (%T) |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 100% |

| 0.1 | 0.79 | 79% |

| 0.3 | 0.50 | 50% |

| 1 | 0.1 | 10% |

| 2 | 0.01 | 1% |

| 3 | 0.001 | 0.1% |

Derivation from First Principles

The law can be derived by considering the attenuation of light through a thin, infinitesimal slice of a solution. The decrease in light intensity, dI, across a thickness dl is proportional to both the original intensity I and the number of absorbing molecules in the path, which is itself proportional to the concentration c. This leads to the differential equation: -dI = μ I dl Here, μ is the Napierian attenuation coefficient. Integrating this equation over a finite path length l yields an exponential decay of intensity: I = I₀ e^(-μ l) By converting from natural logarithms to base-10 logarithms and relating the attenuation coefficient to the concentration (μ ∝ c), one arrives at the familiar form of the Beer-Lambert Law, A = ε l c [14] [8]. This derivation assumes a monochromatic light beam and a homogeneous, non-scattering solution.

Instrumentation and Measurement

Modern UV-Vis spectrophotometers are engineered to make accurate absorbance measurements based on the principles of the Beer-Lambert Law.

Key Instrument Components

A typical spectrophotometer consists of several core components arranged in a specific workflow to measure the absorption of light by a sample.

Figure 1: Workflow of a UV-Vis Spectrophotometer

- Light Source: Provides broad-spectrum electromagnetic radiation. Instruments often use two lamps: a deuterium lamp for the UV range and a tungsten or halogen lamp for the visible range [3].

- Wavelength Selector (Monochromator): This critical component isolates a specific, narrow band of wavelengths from the broad output of the light source. It typically uses a diffraction grating (with a groove frequency of 1200 grooves per mm or higher) to disperse the light and a slit to select the desired wavelength, ensuring that the measurement approximates monochromatic light as required by the BLL [3].

- Sample Cuvette: A container, usually with a standard path length of 1 cm, that holds the solution under investigation. For UV measurements, quartz cuvettes are essential as they are transparent to UV light, unlike glass or plastic [3].

- Detector: Converts the transmitted light intensity into an electrical signal. Common detectors include photomultiplier tubes (PMTs), which are highly sensitive for low-light levels, and photodiodes or charge-coupled devices (CCDs) based on semiconductor technology [3].

- Computer and Readout: Processes the electrical signal from the detector, calculates absorbance using the relationship A = log₁₀(I₀/I), and displays the resulting spectrum or absorbance value [3].

The Critical Role of the Reference Measurement

A fundamental step in the protocol is measuring a reference or "blank" sample. This is a cuvette containing only the solvent and any other chemical species present in the sample solution, except for the target analyte. The intensity of light passing through this reference, I₀, is measured first. This automatically corrects for any light absorption by the solvent or reflection/scattering by the cuvette walls, ensuring that the subsequent sample measurement (I) reflects the absorption due to the analyte alone [3].

Experimental Protocol for Quantitative Analysis

The primary application of the Beer-Lambert Law is determining the concentration of an unknown sample. This is achieved through a method known as calibration, which involves creating a standard curve.

Step-by-Step Calibration and Quantification Protocol

- Wavelength Selection: Identify the wavelength of maximum absorption (λmax) for the target analyte by recording its absorption spectrum (absorbance vs. wavelength). Using λmax maximizes sensitivity and helps minimize deviations from the Beer-Lambert Law [10].

- Preparation of Standard Solutions: Accurately prepare a series of standard solutions with known concentrations of the analyte, ensuring they cover a range that is expected to include the unknown. Use the same solvent and buffer conditions for all standards and the unknown.

- Measurement of Absorbance: Using the selected λ_max, measure the absorbance of the blank solution first to set the 0 absorbance (100% transmittance) baseline. Then, measure the absorbance of each standard solution [3] [10].

- Construction of Calibration Curve: Plot the measured absorbance values of the standard solutions (y-axis) against their respective known concentrations (x-axis).

- Linear Regression Analysis: Fit a straight line to the data points using the least-squares method. For a system obeying the Beer-Lambert Law, the plot will be linear, and the equation of the line will be in the form y = mx + b, where the slope m is equal to εl [10].

- Determination of Unknown Concentration: Measure the absorbance of the unknown sample under identical experimental conditions. Use the calibration curve equation to calculate its concentration: cunknown = (Aunknown - b) / m.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key materials and reagents required for a successful quantitative UV-Vis experiment.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for UV-Vis Quantification

| Item | Function & Importance | Technical Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Standard (Analyte) | Provides the known reference material for constructing the calibration curve. | High-purity reference standard of known identity and purity. |

| Appropriate Solvent | Dissolves the analyte to form a homogeneous solution; its absorbance sets the I₀ baseline. | Must be transparent (non-absorbing) in the spectral region of interest (e.g., water, methanol, buffer). |

| Cuvette | Holds the sample solution in the instrument's fixed light path. | Standard 1 cm path length; Quartz for UV range, glass/plastic for visible only. |

| Buffer Salts | Maintains constant pH and ionic strength, ensuring consistent analyte absorption properties. | Must not absorb at the analytical wavelength or interact chemically with the analyte. |

Limitations and Deviations from the Law

While foundational, the Beer-Lambert Law is an idealization, and several factors can lead to significant deviations from the predicted linear relationship between absorbance and concentration.

Fundamental Limitations

- High Concentrations: The law is most accurate for dilute solutions, typically below 10 mM. At high concentrations, the average distance between absorbing molecules decreases, leading to electrostatic interactions that can alter the absorptivity. Furthermore, changes in the solution's refractive index at high concentrations can also cause deviations [13] [12] [15].

- Chemical Equilibria: If the analyte exists in an equilibrium between two or more species with different absorption spectra (e.g., acid-base indicators), a shift in this equilibrium with concentration will result in a non-linear calibration curve [14].

- Instrumental Factors: The use of non-monochromatic light can lead to deviations. If the bandwidth of the incident light is too wide relative to the narrow absorption peak of the analyte, the measured absorbance will be lower than the true value. Stray light—light reaching the detector at wavelengths outside the intended band—is another common source of error, particularly at high absorbance values, where it can cause a plateau in the calibration curve [3] [15].

Scattering and the Modified Beer-Lambert Law

In turbid or scattering media like biological tissues, blood, or colloidal suspensions, the fundamental assumptions of the BLL are violated. Light is lost from the path not only by absorption but also by scattering. To address this, the Modified Beer-Lambert Law (MBLL) has been developed for applications such as pulse oximetry and near-infrared spectroscopy of tissues [16] [9]. The MBLL introduces a Differential Pathlength Factor (DPF) to account for the increased distance light travels due to scattering, and a geometry-dependent factor G: A = ε · c · l · DPF + G The DPF is typically in the range of 3 to 6 for biological tissues, meaning the actual pathlength light travels is 3 to 6 times longer than the physical separation between the light source and detector [9]. The following diagram visualizes the core factors leading to deviations from the classic law.

Figure 2: Factors Causing Deviations from the Beer-Lambert Law

The Beer-Lambert Law remains a pillar of quantitative analytical science, providing a direct and powerful link between a measurable physical quantity (absorbance) and the concentration of a chemical species. A deep understanding of its mathematical basis, the instrumentation used to apply it, and its well-documented limitations is essential for any researcher employing UV-Vis spectroscopy. For drug development professionals, rigorous application of this law—including careful wavelength selection, systematic calibration, and awareness of potential deviations—ensures the generation of reliable, high-quality data for quantifying analytes, monitoring reactions, and ultimately bringing safe and effective medicines to market. While its core principle is simple, mastery of its nuances and modern modifications, such as the MBLL for scattering media, is what separates a routine measurement from a robust scientific analysis.

In ultraviolet-visible (UV-Vis) spectroscopy, the absorption maximum (λmax) represents the wavelength at which a molecule exhibits its highest absorbance of light, corresponding to the energy required for specific electronic transitions within its structure [17]. The accurate identification of λmax is fundamental for both qualitative identification and quantitative analysis of chemical compounds across pharmaceutical development, materials science, and environmental monitoring [18] [19].

The process of identifying λmax intersects critically with wavelength selection strategies for analyte quantification. Selecting appropriate wavelengths enables researchers to maximize sensitivity for target analytes while minimizing interference from other sample components [20] [21]. This technical guide examines established and emerging methodologies for spectral scanning and interpretation, with emphasis on their application within rigorous analytical workflows for quantitative analysis.

Fundamental Principles of UV-Vis Spectroscopy

Electronic Transitions and Spectral Interpretation

A UV-Vis spectrum plots absorbance against wavelength, where peaks indicate electronic transitions between molecular orbitals [17]. Key transitions include:

- π→π* transitions: Typically occur in conjugated systems at 200-250 nm for dienes, extending to longer wavelengths with increased conjugation

- n→π* transitions: Observed in carbonyl compounds at 270-300 nm with lower intensity

- σ→σ* transitions: Appear below 200 nm in saturated hydrocarbons

- Charge-transfer transitions: Occur in metal complexes across various wavelengths [17]

The Beer-Lambert Law (A = εlc) forms the basis for quantitative analysis, establishing a linear relationship between absorbance (A) and analyte concentration (c), where ε represents molar absorptivity and l the path length [17]. Quantitative accuracy depends on measuring absorbance at optimal wavelengths where the analyte exhibits significant absorption while minimizing interference.

Instrumentation and Wavelength Selection Components

Spectral acquisition requires precise wavelength selection components that isolate specific wavelength regions from broadband light sources [20].

Table 1: Common Wavelength Selection Technologies

| Technology | Operating Principle | Effective Bandwidth | Throughput Efficiency | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Absorption Filters | Selective light absorption by colored glass/polymer | 30-250 nm | ~10% | Simple photometers, educational instruments |

| Interference Filters | Constructive/destructive interference of light waves | 10-20 nm | ≥40% | Portable analyzers, dedicated spectrophotometers |

| Monochromators | Dispersion via prism/grating with slit control | Variable (typically 0.1-5 nm) | Varies with configuration | Research-grade instruments, HPLC detectors |

Modern instrumentation balances bandwidth narrowness for resolution against throughput efficiency for signal-to-noise ratio optimization—a critical consideration for quantitative accuracy [20]. For single-analyte quantification in purified samples, fixed wavelength selection may suffice, while complex mixtures typically require full-spectrum scanning with multivariate analysis [17].

Spectral Scanning Methodologies

Full-Spectrum Scanning

Full-spectrum scanning collects absorbance data across a broad wavelength range (typically 190-900 nm) to characterize all potential absorption features of a sample [17]. This approach provides comprehensive spectral information, enabling:

- Identification of all chromophores present in a sample

- Detection of unexpected absorbing species

- Selection of optimal wavelengths for subsequent quantitative methods

- Assessment of sample purity through spectral profile examination

The methodology involves incrementally advancing the wavelength selector while measuring transmitted light intensity, with modern instruments automating this process via motorized monochromators or diode arrays [20].

Targeted Wavelength Selection

For routine quantification, targeted measurement at specific wavelengths often replaces full-spectrum acquisition. Discrete wavelength selection improves analysis speed and can enhance precision by focusing measurement at spectral regions with maximal analyte information [21]. Advanced approaches include:

- Fixed wavelength monitoring: Using filters or fixed monochromator settings

- Multi-wavelength ratiometric analysis: Combining measurements at multiple wavelengths to correct for background interference

- Dynamic wavelength optimization: Adjusting measurement wavelengths based on real-time assessment of spectral quality [21]

Hyperspectral Imaging Techniques

Advanced scanning methodologies like spatio-spectral scanning acquire spectral and spatial information simultaneously, particularly valuable for heterogeneous samples [22]. This technique generates a three-dimensional data cube (x, y, λ) through:

- Spatial scanning: Collecting complete spectra at each spatial point

- Spectral scanning: Capturing full spatial images at each wavelength

- Spatio-spectral scanning: Acquiring wavelength-coded spatial information through innovative optical designs [22]

Computational Approaches for Wavelength Selection

Traditional Chemometric Methods

Chemometric techniques enhance analytical precision through mathematical processing of spectral data [21]. Established methods include:

- Moving Window Partial Least Squares (MW-PLS): Systematically evaluates contiguous wavelength regions to identify intervals with optimal predictive performance for PLS modeling [21]

- Successive Projections Algorithm (SPA): Minimizes collinearity by selecting wavelengths with minimal redundancy through vector orthogonalization [21]

- Hybrid Linear Analysis (HLA): Utilizes net analyte signal regression to determine wavelengths that maximize analyte-specific information [23]

These approaches effectively address spectral overlap in complex mixtures, though they require careful parameter optimization and validation [23] [21].

Machine Learning and Emerging Computational Techniques

Machine learning (ML) transforms wavelength selection and spectral interpretation through pattern recognition capabilities exceeding traditional methods [18].

Absorbance Value Optimization (AVO) PLS

The AVO-PLS method selects wavelengths based on optimal absorbance ranges rather than spectral regions, recognizing that both high-absorption (noise-dominated) and low-absorption (information-poor) regions compromise model accuracy [21]. The algorithm:

- Eliminates wavelengths with absorbance above an optimized upper threshold

- Discards wavelengths with absorbance below an optimized lower threshold

- Processes the resulting discontinuous wavelength combinations through PLS modeling

- Iteratively refines thresholds to minimize prediction error [21]

Experimental validation analyzing total cholesterol and triglycerides in human serum demonstrated AVO-PLS achieved RMSEP of 0.164 mmol L⁻¹ and Rₚ of 0.990, outperforming MW-PLS and SPA approaches [21].

Artificial Intelligence Integration

ML algorithms, particularly Random Forest models, demonstrate exceptional performance predicting UV-Vis absorption maxima of organic compounds using molecular descriptors [18]. Key advantages include:

- Rapid prediction of λmax without quantum chemical calculations

- High-throughput screening of compound libraries for desired optical properties

- Identification of structure-property relationships guiding molecular design [18]

In pharmaceutical applications, ML-assisted evolutionary design has identified small molecule acceptors for organic solar cells with over 15% efficiency [18].

Table 2: Comparison of Wavelength Selection Methodologies

| Method | Algorithm Type | Key Parameters | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MW-PLS | Continuous wavelength selection | Initial wavelength, window size, PLS factors | Identifies optimal contiguous regions | Limited to single continuous band |

| SPA | Discrete wavelength selection | Number of wavelengths, evaluation function | Minimizes collinearity | May exclude relevant wavelengths |

| AVO-PLS | Multi-band optimization | Upper/lower absorbance bounds | Handles multiple separate bands | Requires absorbance threshold optimization |

| ML/Random Forest | Predictive modeling | Molecular descriptors, ensemble parameters | High-throughput prediction | Requires extensive training data |

Experimental Protocols

Sample Preparation and Measurement

Proper sample preparation ensures accurate spectral interpretation [17]:

Solvent Selection: Choose solvents transparent in the spectral region of interest. Dichloromethane demonstrates minimal UV absorbance, making it suitable for electronic transition studies [18]. Avoid solvents with significant absorption overlap with analytes.

Concentration Optimization: Prepare samples with target absorbance between 0.1-1.0 AU for linear Beer-Lambert behavior. For λmax identification, initial screening at ~0.5 AU maximizes feature detection while avoiding saturation [17].

Path Length Selection: Standard 1 cm path length cuvettes suffice for most applications. Adjust path length or concentration to maintain optimal absorbance range.

Reference Measurement: Measure solvent-filled cuvette as reference to establish baseline. For complex matrices, use matrix-matched references when possible [17].

AVO-PLS Implementation Protocol

Based on hyperlipidemia indicator analysis [21]:

Spectral Acquisition: Collect NIR spectra (780-2498 nm) of human serum samples using transmission mode with 2 nm resolution.

Spectral Preprocessing: Apply Savitzky-Golay smoothing to reduce high-frequency noise while preserving spectral features.

Data Partitioning: Divide dataset into calibration (100 samples) and prediction (100 samples) sets. Perform multiple random partitions (50 iterations) to ensure model robustness.

Absorbance Threshold Optimization: Systematically evaluate upper (Aₘₐₓ) and lower (Aₘᵢₙ) absorbance bounds from 0.1-1.5 AU in 0.01 AU increments.

Wavelength Selection: For each (Aₘᵢₙ, Aₘₐₓ) combination, retain wavelengths where sample absorbance falls within specified range.

Model Building: Develop PLS models for each wavelength subset. Determine optimal number of latent factors through cross-validation.

Model Evaluation: Calculate RMSEP (Root Mean Square Error of Prediction) and Rₚ (Prediction Correlation Coefficient) for each iteration.

Validation: Apply optimized model to independent validation set (102 samples) to assess real-world performance.

Machine Learning Prediction of λmax

Protocol for computational prediction of organic compound λmax [18]:

Dataset Curation: Compile experimental UV-Vis absorption maxima for 1000+ organic compounds in consistent solvent (dichloromethane).

Descriptor Calculation: Compute molecular descriptors (topological, electronic, geometrical) using cheminformatics tools like RDKit.

Model Training: Implement Random Forest regression using 70-80% of data for training. Optimize hyperparameters (tree depth, number of estimators) through cross-validation.

Model Validation: Evaluate predictive performance on held-out test set (20-30% of data) using R² and mean absolute error metrics.

Virtual Screening: Apply trained model to predict λmax for novel compound libraries (20,000 molecules). Prioritize compounds with red-shifted absorption for synthetic evaluation.

Experimental Verification: Synthesize top candidates and validate predicted λmax values experimentally.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Materials for Spectral Analysis and Wavelength Selection

| Item | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Dichloromethane (DCM) | Solvent with minimal UV cutoff | Ideal for electronic transition studies; purify to remove stabilizers [18] |

| Quartz Cuvettes | Sample containment for UV region | Required for wavelengths <350 nm; ensure matched pairs for reference [17] |

| NIST-Traceable Standards | Instrument wavelength calibration | Verify monochromator accuracy at critical wavelengths (e.g., 656.1 nm, 486.1 nm) |

| Holmium Oxide Filter | Wavelength validation standard | Provides characteristic peaks at 241, 279, 287, 333, 345, 361, 416, 451, 536 nm |

| Absorption Reference Materials | Analytical method validation | Certified reference materials for quantitative accuracy verification |

| SG Smoothing Algorithms | Spectral preprocessing | Reduce high-frequency noise while preserving spectral features [21] |

| PLS/Chemometrics Software | Multivariate modeling | Implement MW-PLS, AVO-PLS, and related wavelength selection algorithms [21] |

Troubleshooting and Spectral Interpretation

Common Experimental Artifacts

Solvent Absorption: Solvents with chromophores (e.g., acetone) absorb specific wavelengths, obscuring sample peaks below 330 nm [17]

Stray Light Effects: Imperfect monochromators transmit out-of-band wavelengths, reducing apparent absorbance at high concentrations and compromising Beer-Lambert linearity [20]

Light Scattering: Particulates or bubbles scatter light, disproportionately affecting shorter wavelengths and elevating baseline absorbance [17]

Cuvette Imperfections: Scratches or residues on optical surfaces artificially increase measured absorbance; use spectrometric-grade cuvettes with proper handling [17]

Spectral Shift Interpretation

Bathochromic Shift (Red Shift): Movement of λmax to longer wavelengths indicates increased conjugation, solvent polarity effects, or auxochrome introduction [17]

Hypsochromic Shift (Blue Shift): Movement of λmax to shorter wavelengths suggests decreased conjugation, conformational changes, or solvent interactions [17]

Hyperchromic Effect: Increased absorption intensity typically results from structural changes enhancing transition probability [17]

Hypochromic Effect: Decreased absorption intensity often indicates molecular aggregation or interactions restricting electronic transitions [17]

Future Perspectives

Analytical chemistry trends projected for 2025 emphasize miniaturization, automation, and intelligent data analysis [19]. Key developments include:

Portable Spectrometers: Field-deployable instruments with integrated wavelength selection algorithms enable real-time environmental monitoring and point-of-care diagnostics [19]

AI-Enhanced Interpretation: Machine learning advances will increasingly automate wavelength selection and spectral interpretation, reducing expert dependency [18] [19]

Multi-Omics Integration: Correlation of spectral data with genomic, proteomic, and metabolomic datasets provides comprehensive biological system understanding [19]

Quantum Sensing Technologies: Emerging quantum sensors promise unprecedented sensitivity for trace analyte detection, potentially revolutionizing absorption spectroscopy [19]

These innovations will further embed wavelength selection strategies as critical components in analytical workflows, enhancing both the efficiency and reliability of quantitative UV-Vis analyses.

Ultraviolet-Visible (UV-Vis) spectroscopy is a fundamental analytical technique in scientific research and industrial applications, valued for its ability to provide insights into electronic structure and enable quantitative analysis. The core principle involves measuring the absorption of discrete wavelengths of UV or visible light by a sample, which occurs when electrons are promoted to higher energy states [3]. For researchers in drug development and other fields, accurate quantification of analytes using this technique is paramount. However, a significant challenge lies in the fact that the obtained spectral profile—including the position, intensity, and shape of absorption bands—is not an intrinsic property of the analyte alone. It is profoundly shaped by a triad of factors: the solvent environment, the pH of the solution, and the fundamental molecular structure of the compound under investigation [24]. This guide provides an in-depth examination of these critical influences, framed within the essential context of selecting optimal wavelengths for reliable analyte quantification in UV-Vis research.

Core Influencing Factors and Experimental Evidence

Solvent Effects

The solvent, often mistakenly considered an inert medium, actively participates in solute-solvent interactions that can dramatically alter electronic transitions. These effects are primarily mediated through solvent polarity and hydrogen-bonding capacity [24].

Solvent Polarity and Spectral Shifts: The polarity of a solvent determines how effectively it stabilizes the ground and excited states of a molecule. When the excited state is stabilized more than the ground state by a polar solvent, the energy gap between these states decreases, leading to a bathochromic (red) shift, where absorption moves to longer wavelengths. Conversely, when the ground state is preferentially stabilized, a hypsochromic (blue) shift occurs, moving absorption to shorter wavelengths [24]. For instance, the π→π* excited states of molecules like 3-hydroxyflavone are typically less energetic and more stabilized in ethanol solution compared to the gas phase [25].

Hydrogen Bonding and Specific Interactions: Hydrogen-bonding solvents (e.g., water, methanol) significantly impact electronic transitions, particularly those involving non-bonding (n) electrons. These solvents can stabilize non-bonding electrons in the ground state through hydrogen bonding, which increases the energy required for an n→π* transition, resulting in a pronounced blue shift [25] [24]. A classic example is acetone, whose n→π* band shifts to shorter wavelengths in water compared to non-polar solvents due to hydrogen bonding [24].

Solvent Transparency and Selection: A critical practical consideration is the solvent's cutoff wavelength—the point below which the solvent itself absorbs UV light significantly, interfering with analyte measurement. Choosing a solvent with a cutoff lower than the analyte's absorption region is essential [24]. Table 1 lists the cutoff wavelengths for common solvents used in UV-Vis spectroscopy.

Table 1: UV Cutoff Wavelengths for Common Solvents

| Solvent | UV Cutoff Wavelength (nm) |

|---|---|

| Water | 190 nm |

| Deuterium Oxide (D₂O) | 195 nm |

| Hexane | 195 nm |

| Acetonitrile | 190 nm |

| Methanol | 205 nm |

| Ethanol | 210 nm |

| Chloroform | 245 nm |

Band Shape and Intensity: Polar solvents can also cause broadening of absorption bands. This arises from a variety of solute-solvent interactions and vibrational coupling, which create a range of microenvironments for the solute molecules. For quantitative analysis, maintaining a consistent solvent environment across all samples is crucial for obtaining reproducible intensity measurements [24].

pH and Ionic Environment

The pH of a solution can profoundly affect the UV-Vis spectrum of an analyte, particularly if it contains ionizable functional groups. Changes in pH can alter the electronic structure of the molecule, leading to shifts in absorption maxima and changes in molar absorptivity.

Mechanism of pH Influence: The acidity or alkalinity of a solution can directly affect the position of absorption peaks and the absorption coefficient by promoting protonation or deprotonation of the analyte [26]. For example, the protonated and deprotonated forms of a molecule often possess distinct chromophores, resulting in different absorption spectra. This effect is leveraged in the use of pH-sensitive dyes.

Impact on Water Quality Monitoring: In environmental analytics, pH is a major interfering factor when using UV-Vis spectroscopy to detect parameters like Chemical Oxygen Demand (COD). Variations in pH can alter the spectral baseline and the absorption characteristics of organic and inorganic constituents, complicating quantification and reducing model accuracy if not compensated for [26].

Molecular Structure

The inherent structure of a molecule is the primary determinant of its UV-Vis absorption characteristics. The nature of the chromophores—the light-absorbing parts of the molecule—dictates the possible electronic transitions.

Chromophores and Electronic Transitions: Key chromophores include carbonyl groups (C=O), double and triple bonds (C=C, C≡C), and aromatic rings. Electrons in these systems can undergo several types of transitions, most commonly π→π and n→π [25] [27]. The energy required for these transitions, and thus the wavelength of absorption, is influenced by the extent of the π-system and the presence of substituents. For instance, n→π* states become less stable as the π-conjugated system enlarges [25].

Conjugation and Substituent Effects: Conjugation, the alternation of single and multiple bonds, is a major structural factor that lowers the energy required for π→π* transitions, causing a bathochromic shift. Table 2 provides approximate absorption maxima for common chromophores, illustrating how molecular structure influences the absorption wavelength.

Table 2: Characteristic Absorption Maxima of Common Chromophores

| Chromophore | Example | Transition Type | Approximate λ_max (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acetylene | R-C≡C-R | π→π* | 170 [27] |

| Alkene | >C=C< | π→π* | 175 [27] |

| Carbonyl (Ketone) | R-C=O-R' | n→π* | 280 [27] |

| Primary Amide | R-C=O-NH₂ | n→π* / π→π* | 210 [27] |

| Azo-group | R-N=N-R | n→π* / π→π* | 340 [27] |

| 3-Hydroxyflavone (in non-polar solvent) | Flavonol | π→π* (multiple) | 355, 340, 304 (eV equivalents) [25] |

Intramolecular Interactions: Specific structural features, such as the formation of an intramolecular hydrogen bond (IHB), can significantly modulate solvation and spectral properties. In 3-hydroxyflavone, an IHB between the 3-hydroxyl group and the carbonyl oxygen influences the solvent shift and is key to its unique photophysical properties, including excited-state intramolecular proton transfer (ESIPT) [25].

Advanced Analytical Protocols

Experimental Workflow for Wavelength Selection

The process of selecting an optimal quantification wavelength requires a systematic approach that integrates the factors discussed above. The following workflow outlines the key decision points.

Protocol: Characteristic Wavelength Selection for Complex Mixtures

In complex matrices like natural water, surrogate monitoring using machine learning models is required. This protocol details a robust method for selecting characteristic wavelengths for quantifying specific water quality parameters [28].

1. Materials and Instrumentation:

- UV-Vis Spectrometer: Equipped with a xenon lamp light source and a fiber optic immersion probe (e.g., measuring 200–750 nm).

- Reference Materials: Standard solutions of the target analyte (e.g., potassium hydrogen phthalate for COD/TOC, potassium nitrate for TN/NO₃-N).

- Software: For multivariate analysis (e.g., SPSS, MATLAB, or R with requisite chemometrics packages).

2. Spectral Acquisition and Pre-processing:

- Calibrate the spectrometer by first obtaining a dark spectrum, then a reference spectrum using deionized water.

- Collect UV-Vis absorption spectra for a large set of representative samples (e.g., >200 samples for environmental water).

- For each sample, also measure the reference concentration value using standard methods (e.g., rapid digestion spectrophotometry for COD).

- Pre-process spectra if necessary (e.g., smoothing, baseline correction).

3. Characteristic Wavelength Optimization:

- Apply characteristic wavelength selection algorithms to the full spectral dataset to identify the most informative variables, reducing model complexity.

- Recommended Algorithm: Competitive Adaptive Reweighted Sampling (CARS). This method effectively selects wavelengths with strong correlations to the analyte concentration while eliminating uninformative variables [28].

- Compare the performance of CARS against other methods (e.g., single wavelength, PCA, full spectrum) by evaluating the prediction accuracy of subsequent models.

4. Surrogate Model Building and Validation:

- Use the selected characteristic wavelengths as input variables for machine learning models.

- Recommended Model: Ridge Regression. It has been shown to achieve excellent performance (determination coefficient, R² > 0.96 for TN and NO₃-N) when combined with CARS wavelength selection, offering a good balance of accuracy and interpretability for systems with relatively stable chemical compositions [28].

- Validate the model using a separate prediction set not used in calibration or training. Report the coefficient of determination (R²) and root mean square error (RMSE) for both calibration and prediction sets.

Protocol: Compensation for Environmental Factors (pH, Temperature)

Environmental factors like pH and temperature can introduce significant interference. This protocol describes a data fusion method to compensate for their effects, improving the accuracy of COD detection [26].

1. Sample Collection and Standard Measurement:

- Collect a large number of real-world samples over time to capture natural variations.

- For each sample, immediately measure and record the environmental factors: pH, temperature, and conductivity using a multi-factor portable measuring instrument.

- Determine the reference COD value using standard methods (e.g., Hach rapid digestion spectrophotometry).

2. Spectral and Environmental Data Fusion:

- Acquire the UV-Vis spectrum for each sample (e.g., range 190–1120 nm).

- Fuse the spectral data with the measured environmental factors into a single dataset. This can be achieved by creating a data matrix where each row represents a sample, and columns include absorbances at all wavelengths plus the values for pH, temperature, and conductivity.

- Extract feature wavelengths from the full spectrum using an appropriate algorithm (e.g., CARS).

3. Model Development with Fused Data:

- Establish a prediction model (e.g., using PLS or ridge regression) using the fused data matrix (spectral feature wavelengths + environmental factors) as input and the reference COD values as the output.

- This model inherently learns and compensates for the influence of the environmental factors, as they are directly included as model variables.

4. Performance Comparison:

- Compare the prediction performance (R² and RMSE) of the model built with fused data against a model built using spectral data alone. The fused model should demonstrate significantly improved accuracy and robustness [26].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for UV-Vis Spectral Analysis

| Item | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Spectrometer | Instrument for measuring light absorption; can be a benchtop unit (Agilent Cary 60) or a portable system with an immersion probe for in-situ measurements [28] [26]. |

| Quartz Cuvettes | Sample holders transparent to UV and visible light; required for wavelengths below ~380 nm where glass and plastic absorb strongly [3]. |

| Deuterium (D₂) Lamp | High-intensity light source for the UV range, often paired with a Tungsten/Halogen lamp for the visible range in a single instrument [3]. |

| HPLC-Grade Solvents (e.g., Water, Acetonitrile, Methanol, Hexane) | High-purity solvents with known UV cutoff wavelengths for preparing analyte solutions and establishing blank references [3] [24]. |

| Buffers (e.g., Phosphate, Acetate) | For controlling and maintaining solution pH, which is critical for stabilizing ionizable analytes and ensuring reproducible spectra [26]. |

| Standard Reference Materials (e.g., KHP, Potassium Nitrate) | Pure compounds used to prepare calibration standards with known concentrations for quantitative model development [28]. |

| Dark Current Solution | A non-reflective, light-absorbing solution or a sealed cap used to measure the instrument's dark spectrum/dark current for baseline calibration [28]. |

The accurate selection of a quantification wavelength in UV-Vis spectroscopy is a sophisticated process that extends beyond simply identifying the absorption maximum of a pure standard. It requires a comprehensive understanding of the intricate interplay between the analyte's molecular structure, the solvent environment, and the solution pH. As demonstrated, solvents can induce significant spectral shifts, pH can alter the very nature of the chromophore, and the molecular structure dictates the fundamental absorption properties. For complex analytical challenges, particularly in non-ideal matrices, advanced protocols involving characteristic wavelength selection and data fusion with environmental factors provide a robust path to high-fidelity results. By systematically applying the principles and methodologies outlined in this guide, researchers and drug development professionals can enhance the reliability of their quantitative UV-Vis analyses, ensuring that their data is not only precise but also chemically meaningful.

Advanced Wavelength Selection Methods for Pharmaceutical Compounds and Complex Mixtures

Ultraviolet-Visible (UV-Vis) spectroscopy remains a cornerstone technique for quantitative analysis in research and development, particularly in pharmaceutical and environmental sciences. The accurate quantification of a single analyte hinges on the precise selection of its measurement wavelength. This selection is not merely a procedural step but a critical analytical decision that directly influences method sensitivity, specificity, and robustness [3] [29]. Within the broader context of developing a robust analytical method, wavelength selection represents the foundation upon which a reliable calibration model is built. An inappropriate choice can lead to deviations from the Beer-Lambert law, increased interference, and ultimately, inaccurate concentration measurements [29]. This guide provides a systematic framework for wavelength selection, integrating fundamental principles, advanced computational approaches, and practical validation protocols tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

Theoretical Foundations of Wavelength Selection

The process of wavelength selection is guided by the interplay between the analyte's intrinsic properties and the instrumental parameters of the spectrophotometer. The fundamental principle is derived from the Beer-Lambert law, which states that the absorbance (A) of a solution is directly proportional to the concentration (c) of the absorbing species, the path length (L) of the measurement, and its molar absorptivity (ε) at a specific wavelength [30] [29]. The law is expressed as: A = ε c L

The molar absorptivity (ε), also known as the extinction coefficient, is a wavelength-dependent property that quantifies how strongly a chemical species absorbs light at a given wavelength [29]. Consequently, selecting a wavelength where the analyte has a high molar absorptivity directly enhances the sensitivity of the quantification method, allowing for the detection of lower concentrations.

A UV-Vis spectrophotometer functions by passing a beam of light from a source (e.g., a xenon or deuterium lamp) through a monochromator, which selects a narrow band of wavelengths. This monochromatic light passes through the sample, and a detector measures the intensity of the transmitted light relative to a blank reference [3] [30]. The instrument's spectral bandwidth, defined as the range of wavelengths transmitted at half the maximum intensity, is a key parameter. A narrower spectral bandwidth provides higher resolution, which is crucial for accurately characterizing sharp absorption peaks and avoiding deviations from the Beer-Lambert law [29].

A Systematic Workflow for Wavelength Selection

A structured approach to wavelength selection mitigates the risk of analytical error. The following workflow outlines the primary stages, from initial profiling to final confirmation.

Figure 1: A systematic workflow for selecting an optimal wavelength for single-analyte quantification, integrating experimental inputs and decision points.

Initial Spectral Profiling and Candidate Identification

The first step involves obtaining the full absorption spectrum of a pure standard solution of the analyte across the UV-Vis range (typically 200-800 nm) [30]. This profile serves as a fingerprint, revealing one or more absorption peaks (maxima) and their corresponding molar absorptivities.

- Primary Criterion: λₘₐₓ : The wavelength of maximum absorbance (λₘₐₓ) is the primary candidate for quantification. At this point, the rate of change of absorbance with wavelength is minimal, which reduces potential inaccuracies caused by small instrumental errors in wavelength calibration (wavelength error) [29].

- Secondary Candidates: In complex matrices, a secondary, well-defined peak with high absorptivity may be preferable to the global maximum if it avoids spectral overlap with interferents.

Interference and Matrix Assessment

In real-world applications, the analyte is rarely measured in pure solution. The sample matrix (e.g., excipients in a drug formulation, or dissolved organic matter in water) may contain other substances that absorb light.

- Matrix Blank Scan: The absorption spectrum of the blank matrix (containing all components except the analyte) must be obtained [3]. A suitable wavelength is one where the absorbance from the matrix is minimal.

- Specificity Check: The chosen wavelength should demonstrate high specificity for the analyte. The ideal candidate wavelength shows high absorbance for the analyte and negligible absorbance from the matrix and known potential interferents [28].

Evaluation of Analytical Figures of Merit

The final selection is guided by quantitative performance metrics derived from a series of calibration standards measured at the candidate wavelengths.

Table 1: Key Analytical Figures of Merit for Wavelength Comparison

| Figure of Merit | Description | Interpretation for Wavelength Selection |

|---|---|---|

| Linear Dynamic Range | The concentration range over which the Beer-Lambert law holds [29]. | A wider linear range at a candidate wavelength indicates greater method robustness. |

| Sensitivity | Proportional to the molar absorptivity (ε) and the slope of the calibration curve [29]. | A higher slope signifies better ability to distinguish small concentration changes. |

| Limit of Detection (LOD) | The lowest concentration that can be detected [31]. | A lower LOD is preferred, often correlated with higher sensitivity. |

| Signal-to-Noise Ratio | The ratio of the analyte signal to the background noise. | A wavelength with a higher signal-to-noise ratio improves measurement precision. |

Advanced Computational Approaches

For analyses requiring high precision or dealing with complex, overlapping spectra, advanced computational and algorithm-driven methods can enhance the wavelength selection process beyond manual inspection.

Wavelength Selection Algorithms

These algorithms statistically identify the most informative wavelengths for building a predictive calibration model, reducing model complexity and improving accuracy by eliminating uninformative variables [28].

Table 2: Comparison of Characteristic Wavelength Optimization Algorithms

| Algorithm | Primary Mechanism | Reported Advantages |

|---|---|---|

| Competitive Adaptive Reweighted Sampling (CARS) | Iteratively selects wavelengths with large absolute regression coefficients and removes those with small weights [28]. | In one study, CARS combined with Ridge Regression significantly improved prediction for TOC, COD, TN, and NO₃-N in water [28]. |

| Firefly Algorithm (FA) | A nature-inspired metaheuristic that optimizes variable selection by mimicking firefly flashing behavior [31]. | Effectively simplified ANN models for drug quantification, leading to lower prediction error (RRMSEP) compared to full-spectrum models [31]. |

| Genetic Algorithm (GA) | Uses principles of natural selection (crossover, mutation) to evolve towards an optimal set of wavelengths. | Not explicitly detailed in results, but commonly used for variable selection in spectroscopy [31]. |

| Principal Component Analysis (PCA) | A dimensionality reduction technique that transforms original wavelengths into a smaller set of uncorrelated principal components [28]. | Less effective for direct wavelength selection compared to CARS, as it does not select original wavelengths but transforms them [28]. |

Machine Learning Integration

Machine learning models, particularly Artificial Neural Networks (ANN), can model complex, non-linear relationships between absorbance and concentration. When coupled with wavelength selection algorithms like the Firefly Algorithm, these models can achieve high accuracy even with overlapping spectral features, as demonstrated in the simultaneous determination of cardiovascular drugs [31].

Figure 2: A hybrid workflow combining the Firefly Algorithm for wavelength selection with an Artificial Neural Network for concentration prediction, enhancing model performance [31].

Experimental Protocols and Validation

Detailed Protocol: Wavelength Selection and Calibration

This protocol provides a step-by-step methodology for establishing a wavelength-based quantification method.

Instrument Preparation:

- Power on the UV-Vis spectrophotometer and allow the lamp to warm up for the time specified by the manufacturer (typically 15-30 minutes).

- Select a quartz cuvette with a known path length (e.g., 1 cm) for measurements in the UV range [3].

- Perform any necessary instrument initialization and calibration as per the operational manual.

Solution Preparation:

- Stock Standard Solution: Accurately weigh and dissolve the pure analyte in a suitable solvent to prepare a stock solution of known, high concentration (e.g., 100 µg/mL) [31].

- Calibration Standards: Sequentially dilute the stock solution with the solvent to prepare a series of at least 5-7 standard solutions covering the expected concentration range of the samples.

- Blank Solution: Prepare the pure solvent or the sample matrix without the analyte.

Spectral Scanning:

- Place the blank solution in the cuvette and record a baseline spectrum or set the instrument to 100% transmittance (zero absorbance) at the wavelengths of interest [3] [30].

- Replace the blank with the most concentrated standard solution. Record the full absorption spectrum from 200 nm to at least 100 nm beyond the suspected λₘₐₓ.

- Identify the wavelength of maximum absorbance (λₘₐₓ) and any other prominent peaks as candidate wavelengths.

Interference Check:

- Scan the spectrum of the sample matrix (e.g., placebo formulation, environmental water sample) that does not contain the analyte.

- Overlay this spectrum with the analyte spectrum. Candidate wavelengths where the matrix shows minimal absorption are preferred.

Calibration Curve Construction:

- Measure the absorbance of each calibration standard at the primary candidate wavelength (λₘₐₓ) and any secondary candidates.

- Plot absorbance versus concentration for each wavelength and perform linear regression analysis.

- Evaluate the correlation coefficient (R²), slope, and y-intercept for each calibration curve. The wavelength yielding the highest R² and slope (sensitivity) is typically selected.

Validation and Troubleshooting

Once a wavelength is selected, the method must be validated. Key parameters include accuracy, precision, LOD, and LOQ, assessed as per ICH guidelines [31].

- Stray Light: This is light of unintended wavelengths reaching the detector, which can cause non-linearity at high absorbances. It is critical to ensure the instrument's stray light performance is acceptable for the absorbance range being measured [29].

- Deviations from Beer-Lambert Law: These can occur at high concentrations due to chemical associations or electrostatic interactions. If observed, the sample should be diluted to fall within the linear range of the method [29].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Materials and Equipment for UV-Vis Based Quantification

| Item | Function / Description | Critical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| High-Purity Analyte Standard | Serves as the reference material for method development and calibration. | Purity should be verified and certified if possible (>98%) [31]. |

| Spectrophotometric Grade Solvent | Dissolves the analyte and serves as the blank and dilution medium. | Must be transparent in the spectral region of interest; common choices are water, methanol, or ethanol [29]. |

| Quartz Cuvettes | Holds the sample solution in the light path. | Required for UV range measurements below ~350 nm; glass or plastic may be used for visible only [3]. |