Surrogate and Global Optimization in Chemistry: Fundamentals, Methods, and Applications in Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive overview of surrogate-based and global optimization strategies essential for tackling complex, computationally expensive problems in chemical research and drug development.

Surrogate and Global Optimization in Chemistry: Fundamentals, Methods, and Applications in Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of surrogate-based and global optimization strategies essential for tackling complex, computationally expensive problems in chemical research and drug development. It covers foundational concepts, including the definition of surrogate models and the critical challenge of navigating high-dimensional potential energy surfaces to find global minima. The piece explores a wide array of methodological approaches, from established stochastic and deterministic algorithms to cutting-edge Bayesian optimization and machine learning hybrids, highlighting their practical applications in molecular design and Quantitative Systems Pharmacology (QSP). Furthermore, it addresses key challenges such as the curse of dimensionality and hidden constraints, offering troubleshooting and optimization strategies. The discussion extends to validation techniques and performance comparisons of different algorithms, concluding with a forward-looking perspective on the transformative impact of these optimization methods on the acceleration of biomedical discovery.

Core Concepts: Demystifying Surrogate Models and Global Optimization Landscapes

In the pursuit of novel chemical compounds and optimized processes, researchers in chemistry and drug discovery frequently encounter complex systems that are both computationally and experimentally prohibitive to evaluate. These systems, often modeled through high-fidelity simulations or real-world lab experiments, can be characterized as expensive black-box functions [1] [2]. In this context, "black-box" signifies that the internal mechanics of the function are unknown or inaccessible; the user can only provide inputs and observe outputs. "Expensive" denotes that each function evaluation is costly, whether in terms of computational time, financial resources, or the consumption of rare materials [3] [1]. The core challenge is to find the optimal input parameters that minimize or maximize the output of this function while navigating a vast search space and adhering to constraints, all with a severely limited evaluation budget.

This challenge sits at the heart of a broader thesis on global optimization in chemistry research. Traditional gradient-based optimization methods are often inapplicable because derivatives of the black-box function are unavailable [2]. Furthermore, the high cost of evaluation renders exhaustive sampling or naive trial-and-error approaches impractical. This necessitates sophisticated optimization strategies, such as surrogate-based optimization and Bayesian optimization, which aim to guide the search for the optimum with a minimal number of function evaluations [3] [4]. This guide details the fundamental nature of this problem, the methodologies developed to address it, and their practical application in chemical research.

Problem Formulation and Core Concepts

The optimization of an expensive black-box function can be formally defined. Given a black-box function ( f(x) ), the goal is to find a design variable ( x ) that solves the constrained problem defined in the Expensive Black-Box Optimization for Chemical Engineering applications [3]:

[ \min{x} f(x) ] subject to: [ gk(x) \leq 0, \quad k = 1, \dots, K ] [ x^L \leq x \leq x^U ]

Here, ( x ) represents a vector of continuous decision variables (e.g., temperature, concentration, molecular design parameters) bounded between lower and upper limits ( x^L ) and ( x^U ). The function ( f(x) ) is the expensive black-box objective, and ( g_k(x) ) represent a set of ( K ) black-box constraint functions. The variable ( \omega ) may be included to denote potential stochasticity in the system, reflecting real-world uncertainties where the same input ( x ) does not always yield the same output [3].

In many real-world scenarios, the objective function must account for uncontrollable uncertainties, such as fluctuating raw material properties or stochastic reaction yields. This leads to the Stochastic Offline Black-Box Optimization (SOBBO) framework [1]:

[ \theta^{\star} \in \mathop{\mathrm{argmin}}{\theta \in \Theta} \left{ \nu(\theta) = \mathbb{E}{X}\left[g(\theta, X)\right] \right} ]

In this formulation, ( X ) is a random variable representing stochasticity, and the goal is to find a design ( \theta^{\star} ) that is optimal in expectation over all possible values of ( X ) [1].

What Makes a Problem "Expensive"?

An evaluation is considered "expensive" if it meets one or more of the following criteria:

- Computational Cost: A single function evaluation may require hours or days of simulation on high-performance computing clusters. Examples include computational fluid dynamics or high-fidelity process simulations [2].

- Experimental Cost: In drug discovery, a single function evaluation could correspond to synthesizing a new compound and testing its efficacy and toxicity, a process that consumes significant time, specialized expertise, and expensive reagents [1] [4].

- Financial Cost: Each data point may involve costly assays, rare chemical catalysts, or specialized equipment.

- Time Cost: The process of setting up and running an experiment or simulation may be inherently time-consuming, creating a bottleneck in research and development pipelines.

Methodologies for Expensive Black-Box Optimization

The high cost of function evaluations has driven the development of sample-efficient optimization algorithms. The following table summarizes the key methodologies.

Table 1: Key Methodologies for Expensive Black-Box Optimization

| Methodology | Core Principle | Key Features | Typical Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bayesian Optimization (BO) [4] | Builds a probabilistic surrogate model (e.g., Gaussian Process) of the black-box function and uses an acquisition function to guide the search. | Highly sample-efficient; naturally balances exploration and exploitation. | Hyperparameter tuning, drug molecule design, catalyst optimization. |

| Surrogate-Based Optimization [2] | Constructs a deterministic surrogate model (e.g., Neural Network) from an initial dataset and optimizes the surrogate directly. | Can leverage fixed a priori samples; performance depends heavily on surrogate accuracy. | Process optimization where initial simulations are available. |

| Model-Based Optimization (e.g., CUATRO) [3] | A trust-region method that uses local surrogate models to solve the optimization problem. | Can handle black-box constraints; offers both local and global variants. | Chemical engineering applications with explicit constraints. |

| Direct Search (e.g., DIRECT-L) [3] | A deterministic sampling algorithm that recursively divides the search space into smaller hyper-rectangles. | Derivative-free; provably converges to a global optimum for Lipschitz continuous functions. | Lower-dimensional problems where deterministic behavior is valued. |

| Stochastic Offline BBO [1] | Optimizes a black-box function in expectation using only a pre-existing historical dataset, without active queries. | Tailored for different data regimes (large vs. scarce); incorporates uncontrollable uncertainties. | Communication network design, optimization based on historical lab data. |

Two predominant paradigms have emerged for utilizing surrogates in optimization:

- Optimization of Fixed A Priori Surrogates: A dataset is collected by running a fixed set of high-fidelity simulations or experiments. A surrogate model is then trained on this data and is subsequently embedded within a traditional equation-based optimization solver to locate the optimum [2].

- Adaptive Sampling (Surrogate-Guided) Methods: An initial surrogate model is built from a small set of samples. The model's predictions are then used to intelligently select the next sample point, often by optimizing an acquisition function. The model is updated with new data, and the process repeats iteratively [2]. Research shows that adaptive sampling methods are generally more efficient and consistent than fixed-sampling strategies [2].

A critical advancement is the use of Hybrid or Multi-Fidelity Surrogate Models (MFSMs). These models combine a small set of high-fidelity (HF) data with a larger set of inexpensive, approximate low-fidelity (LF) data. The LF model, which might be a simplified physics model or a faster simulation, is "corrected" using the HF data. Studies demonstrate that hybrid modeling improves surrogate robustness and reduces solution variability with fewer high-fidelity samples, albeit at the cost of increased optimization complexity [2].

Experimental Protocols and Case Studies in Chemistry

General Workflow for Surrogate-Based Optimization

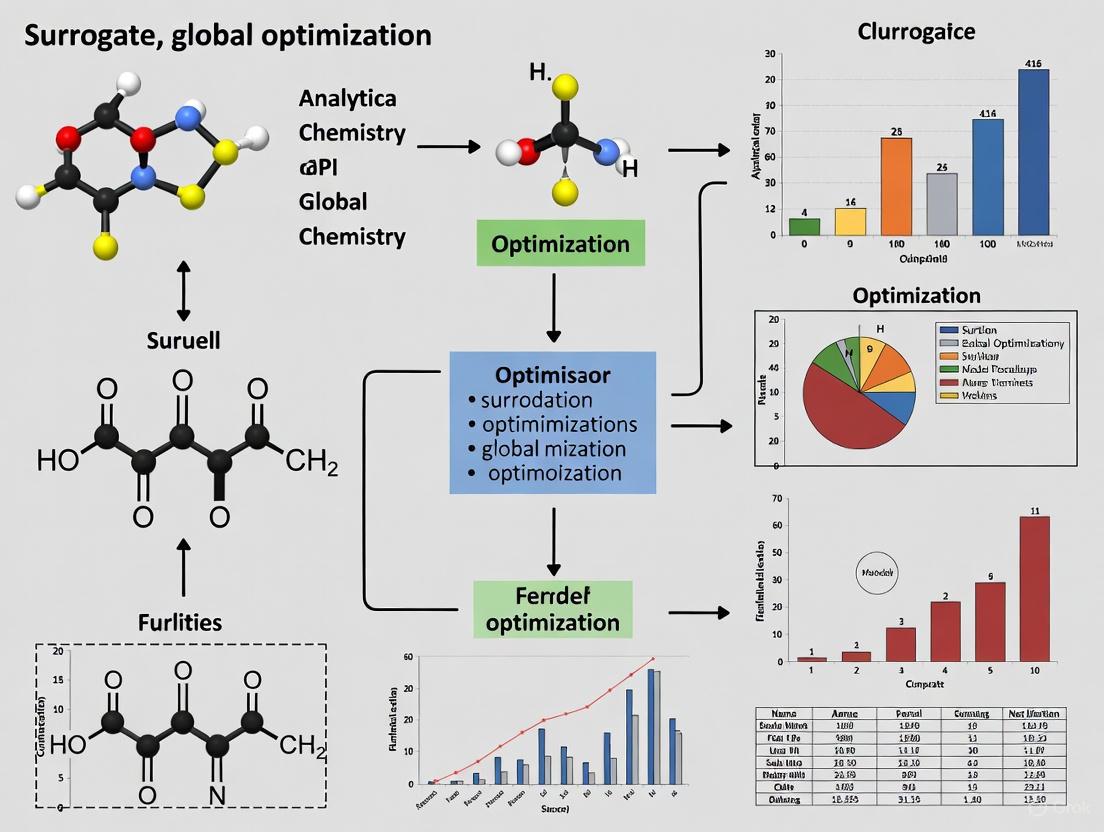

The following diagram illustrates the standard workflow for optimizing an expensive black-box function using adaptive sampling and surrogate models.

Case Study: Bayesian Optimization in Drug Discovery

Drug discovery is a prime example of expensive black-box optimization. The goal is to find a molecule ( \theta ) that maximizes a desired property (e.g., binding affinity) while satisfying multiple constraints (e.g., synthetic accessibility, low toxicity). Evaluating a molecule typically requires expensive and time-consuming wet-lab experiments or high-fidelity molecular simulations [4].

Protocol for BO in Drug Discovery:

- Problem Definition: Define the molecular search space (e.g., a set of permissible chemical transformations or a finite library of compounds).

- Initialization: Select an initial set of molecules, often via random sampling or from historical data.

- Evaluation: Test the initial molecules in the assay (the black-box function) to obtain property data.

- Surrogate Modeling: Train a Gaussian Process model on the collected (molecule, property) data.

- Acquisition: Use an acquisition function (e.g., Expected Improvement) to propose the next most promising molecule to evaluate. This function balances exploring uncertain regions and exploiting known high-performing areas.

- Iteration: Repeat steps 3-5 until the experimental budget is exhausted or a satisfactory molecule is found.

The following table summarizes key case studies and their findings, highlighting the quantitative performance of different algorithms.

Table 2: Case Studies in Chemical and Process Engineering Optimization

| Case Study | Dimension | Key Algorithms Tested | Performance Findings | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Real-Time Optimization (RTO) | 2-d | Bayesian Optimization, CUATRO, DIRECT-L | Model-based methods (BO, CUATRO) found the optimum in the lowest number of function evaluations. | [3] |

| Self-Optimizing Reactor | 2-d | Bayesian Optimization, CUATRO, DIRECT-L | Algorithms were evaluated on their ability to handle deterministic and stochastic, constrained, convex problems. | [3] |

| PID Controller Tuning | 4-d | Bayesian Optimization, CUATRO, DIRECT-L | Comparison was based on performance in both deterministic and stochastic environments. | [3] |

| Extractive Distillation | N/A | Fixed-Sampling vs. Adaptive Sampling with Hybrid Surrogates | Adaptive sampling methods were more efficient. Hybrid modeling improved robustness with fewer samples. | [2] |

| Temperature Vacuum Swing Adsorption | N/A | Fixed-Sampling vs. Adaptive Sampling with Hybrid Surrogates | Hybrid modeling reduced solution variability, though it increased optimization computational cost. | [2] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

In the context of in silico optimization, the "research reagents" are the computational tools and data sources that enable the construction and validation of surrogate models.

Table 3: Key Computational Tools and Data for Black-Box Optimization

| Tool / Resource | Function | Relevance to Optimization |

|---|---|---|

| High-Fidelity (HF) Simulator [2] | A detailed, computationally expensive model of a chemical process or molecular system. | Serves as the "ground truth" black-box function; its evaluations are used to train and validate surrogates. |

| Low-Fidelity (LF) Model [2] | A faster, approximate version of the HF model, often based on simplified physics. | Used in hybrid modeling to provide cheap, abundant data, improving surrogate accuracy with fewer HF samples. |

| Gaussian Process (GP) [4] | A probabilistic model that provides a prediction and an uncertainty estimate. | The most common surrogate model in Bayesian Optimization; its uncertainty quantification is key for acquisition functions. |

| Neural Network (NN) [2] | A flexible, deterministic function approximator. | Used as a surrogate model in fixed-sample and adaptive sampling frameworks; embedded in optimization solvers via tools like OMLT. |

| Optimization & Machine Learning Toolkit (OMLT) [2] | A framework that converts trained ML models into optimization problem formulations. | Allows surrogates (e.g., NNs) to be directly used and optimized within deterministic solvers. |

| Historical Dataset (( \mathcal{D} )) [1] | A pre-existing collection of input-output pairs from the black-box system. | Enables offline optimization (SOBBO) where active querying of the HF function is not possible. |

Visualization of Algorithm Comparison

A critical aspect of benchmarking is visualizing the performance of different algorithms as they converge toward an optimum. The following diagram illustrates the typical convergence profiles of different algorithm classes, which is a standard result in empirical studies [3] [2].

The optimization of expensive black-box functions represents a significant challenge in chemical engineering and drug discovery. The prohibitive cost of evaluation necessitates a shift from traditional optimization methods towards more sophisticated, sample-efficient strategies. As outlined in this guide, surrogate-based approaches, particularly Bayesian optimization and adaptive sampling with hybrid models, have emerged as powerful frameworks for addressing this challenge. They enable researchers to navigate complex, high-dimensional search spaces and find optimal solutions under strict evaluation budgets. The continued development of these methodologies, coupled with integration into user-friendly computational toolkits, is fundamental to accelerating research and development cycles in chemistry and beyond. The choice of a specific algorithm ultimately depends on the problem's characteristics—its dimensionality, degree of stochasticity, constraint structure, and the availability of prior data or low-fidelity models.

What are Surrogate Models? The Role of Metamodels in Computational Efficiency

Surrogate models, also known as metamodels, are simplified mathematical approximations of complex, computationally expensive simulation models. They serve as efficient proxies, enabling rapid exploration of design spaces and optimization in fields where direct simulation is prohibitively resource-intensive. This technical guide delineates the core principles, methodologies, and applications of surrogate models, with a specific emphasis on their transformative role in enhancing computational efficiency within chemical research and drug development. By providing a comprehensive overview of model types, development protocols, and performance metrics, this whitepaper aims to equip researchers and scientists with the knowledge to deploy these powerful tools for accelerating discovery and innovation.

In the realm of engineering and scientific computing, high-fidelity models—such as those based on Finite Element Analysis (FEA), Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD), or detailed molecular dynamics—provide invaluable insights but often at a formidable computational cost. Solving these systems can have a computational complexity of (O(N^3)), meaning that doubling the number of nodes in a simulation can lead to an eightfold increase in computational operations [5]. This cost becomes a critical bottleneck in applications requiring repeated model evaluations, such as sensitivity analysis, uncertainty quantification, and global optimization.

Surrogate models address this challenge directly. A surrogate model is an engineering method used when an outcome of interest cannot be easily measured or computed directly, necessitating an approximate model or a substitute for it [5]. In essence, a surrogate is a computationally inexpensive approximation of an input-output relationship of a complex system. It is constructed from a limited set of carefully chosen data points obtained by running the original, high-fidelity "parent" model. Once built and validated, the surrogate can be used in place of the original model for specific tasks, leading to significant computational savings—often on the order of 10,000 times faster while maintaining errors of less than 1% in some reported cases [6]. This efficiency is paramount within chemistry and drug development, where it enables complex tasks like force field parameterization and process optimization that would otherwise be infeasible [7] [6].

Core Concepts and Quantitative Benefits

The fundamental value proposition of surrogate modeling lies in the trade-off between computational speed and acceptable accuracy. The core idea is to replace a slow, high-fidelity model ( y = f(x) ) with a fast, approximate model ( \hat{y} = \hat{f}(x) ).

The Metamodeling Process and Efficiency Gains

The process involves using probability distribution functions (PDFs) of the inputs to run a detailed parent model thousands of times [8]. The outputs from these runs are then used to determine the coefficients of and test the precision of the metamodel. Studies have demonstrated that deviations between the metamodel and the parent model for many important species can have a weighted RMS error of less than 10%, and in many cases, even less than 1% [8]. The transition from a computationally expensive model to a surrogate can lead to speed-ups on the order of 10,000 while keeping the root mean squared error (RMSE) below 1% in applications like modeling once-through steam generators [6].

Quantitative Performance of Surrogate Models

Table 1: Documented Performance of Surrogate Models in Various Applications

| Application Field | Reported Computational Savings | Reported Accuracy | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Once-Through Steam Generators (OTSGs) | Speed-ups ~10,000x | RMSE < 1% | [6] |

| Urban Chemistry Metamodel (for O₃, CO, NOₓ) | Not explicitly stated | Weighted RMS error < 10% (often <1%) | [8] |

| Global Sensitivity Analysis (Wastewater Treatment) | Much faster computation times | Sobol' indices showed "great similarity" with Monte Carlo | [9] |

| Crude Oil Distillation Unit Modeling | Significant cost reduction for optimization | Approximation error within "maximum allowable tolerance" | [6] |

Types of Surrogate Models and Their Applications

Different surrogate modeling techniques offer distinct advantages and are suited to specific types of problems. The selection of an appropriate model depends on the nature of the data, the desired output, and the need for features like uncertainty quantification.

Comparative Analysis of Model Types

Table 2: Comparison of Common Surrogate Modeling Techniques

| Model Type | Key Strengths | Common Applications in Chemistry/Engineering | Notable Weaknesses |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polynomial Chaos Expansion (PCE) | Efficient for uncertainty quantification; works with probabilistic inputs. | Building fast urban chemistry models for inclusion in global climate models [8]. | May struggle with highly complex, non-linear systems at lower orders [8]. |

| Gaussian Process (GP) / Kriging | Provides uncertainty estimates (variance) with predictions; highly accurate interpolation. | Spatial data prediction, geostatistics, optimization of computer experiments [10] [6]. | Computationally intensive for large datasets due to matrix inversion [10]. |

| Radial Basis Function (RBF) | High flexibility for function approximation; effective for smooth, localized modeling. | Real-time monitoring and prediction in ship design optimization [10]. | Performance sensitive to parameter choices; can overfit noisy data [10]. |

| Support Vector Machine (SVM) | Effective in high-dimensional spaces; strong performance for classification and regression. | Classifying feasible/infeasible regions in process optimization [6]. | Performance can degrade with highly overlapping or noisy data [10]. |

| Artificial Neural Network (ANN) | Powerful for capturing complex, non-linear relationships; data-driven. | Surrogate modeling of crude oil distillation units [6]. | Requires a large amount of data for training; "black box" nature. |

| Genetic Programming (GP) | Discovers symbolic relationships; generates structured model representations. | Building robust metamodels for turbulent flow in pipe bends [11]. | Can produce overly complex models if not constrained. |

Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

The development of a reliable surrogate model follows a structured, iterative workflow. This section outlines a generalized protocol, adaptable to various modeling techniques and applications.

Surrogate Model Development Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the key stages in creating and deploying a surrogate model.

Detailed Experimental Protocol

Step 1: Define Modeling Objectives and Input/Output Variables

- Objective: Clearly articulate the goal of the surrogate model (e.g., global optimization, sensitivity analysis, real-time prediction).

- Input Selection: Identify the independent variables (degrees of freedom) of the process and specify their boundaries. For example, in force field optimization, these are the Lennard-Jones parameters [7]. In a chemical process, they could be temperature, pressure, and concentration [6].

- Output Definition: Define the dependent variables or responses of interest. Examples include product yield, physical properties, or system compliance [6].

Step 2: Sampling the Design Space (Design of Experiments)

- Objective: Generate a set of input data points that efficiently cover the domain of variation.

- Protocol:

- Choose a Sampling Algorithm:

- Determine Sample Size: The number of sample points ((N)) is critical. An experimental design size of 200 has been found adequate for some wastewater treatment models, but this depends on model complexity [9]. Start with a feasible number (e.g., 100-500) for the initial surrogate.

Step 3: Run High-Fidelity Model (Data Generation)

- Objective: Execute the rigorous, high-fidelity model for each sample point generated in Step 2.

- Protocol:

- Automate the process via an interface between the simulation software (e.g., Aspen HYSYS, CAMx, COMSOL) and a data processing environment (e.g., MATLAB, Python) [6].

- Record the output data for each input sample. This forms the matrix of observations used for training.

Step 4: Construct the Surrogate Model

- Objective: Use the input-output data to train a surrogate model.

- Protocol for Gaussian Process/Kriging Model:

- Build the Model: Use the learning sample (training data) to construct the surrogate. The Gaussian Process is defined by a mean function and a covariance (kernel) function that captures the spatial correlation between data points [9] [6].

- Estimate Confidence Intervals: Utilize the internal model structure of the GP or bootstrap methods to estimate confidence intervals for the predictions [9].

Step 5: Validate the Surrogate Model

- Objective: Assess the accuracy and predictive power of the surrogate on unseen data.

- Protocol:

- Data Splitting: Split the generated data into a training set (e.g., 75%) and a validation set (e.g., 25%) [6].

- Statistical Validation: Calculate statistical metrics to compare the surrogate's predictions against the true model outputs from the validation set. Key metrics include:

- Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE)

- Weighted RMS Error (target: <10%, often <1% for key outputs) [8]

- R² (Coefficient of Determination)

Step 6: Deploy for Intended Application

- Objective: Use the validated surrogate model for its designed purpose.

- Protocol:

- Global Optimization: The surrogate replaces the complex model within an optimization loop, allowing for rapid evaluation of the objective function and enabling global searches that can escape local minima [7].

- Sensitivity Analysis: Calculate variance-based Sobol' indices directly from the surrogate to understand the influence of input parameters on output uncertainty [9].

Step 7: Adaptive Refinement (Optional)

- Objective: Improve surrogate accuracy iteratively, especially in regions of interest or high error.

- Protocol: If validation reveals insufficient accuracy, use an adaptive sampling algorithm. This algorithm explores the solution space by iteratively building surrogates and adding new sample points in regions with high predicted error or high non-linearity [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Surrogate Modeling

The development and application of surrogate models rely on a suite of computational tools and statistical reagents.

Table 3: Essential "Research Reagents" for Surrogate Model Development

| Tool/Reagent | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Latin Hypercube Sampling (LHS) | A statistical method for generating a near-random sample of parameter values from a multidimensional distribution. It ensures that the entire design space is covered without requiring an excessively large sample size. | Creating the initial experimental design for building a surrogate of a chemical reactor [6]. |

| Sobol Sequence | A quasi-random low-discrepancy sequence. It is designed to cover the design space more uniformly than random sampling, leading to faster convergence in integration and approximation problems. | Generating input samples for global sensitivity analysis of a wastewater treatment plant model [9]. |

| Polynomial Chaos Expansion (PCE) | A framework for constructing surrogates that explicitly represents the uncertainty in model outputs due to uncertain inputs. It uses orthogonal polynomials in the random inputs. | Developing a fast, urban chemistry metamodel for inclusion in global climate models [8]. |

| Gaussian Process Regression (GPR) | A non-parametric Bayesian modeling technique. It provides a posterior probability distribution over the output, giving not just a prediction but also an estimate of the uncertainty (variance) at any point in the input space. | Building a surrogate for a once-through steam generator (OTSG) for real-time operational optimization [6]. |

| Bootstrap Method | A resampling technique used to estimate statistics on a population by sampling a dataset with replacement. It is used to estimate confidence intervals for sensitivity indices or other model outputs [9]. | Estimating confidence intervals for Sobol' sensitivity indices derived from a Polynomial Chaos Expansion model [9]. |

| Support Vector Machine (SVM) | A supervised learning model used for classification and regression. In surrogate modeling, it can be used to define feasible regions within the solution space, ensuring optimization converges to a feasible solution [6]. | Classifying process conditions as feasible or infeasible during the optimization of a crude oil distillation unit [6]. |

Application in Chemistry Research: A Case Study on Force Field Optimization

The optimization of force field parameters in molecular dynamics is a prime example where surrogate modeling is revolutionizing computational chemistry.

Multi-Fidelity Optimization with Gaussian Processes

A key challenge in training force field parameters, such as those in the Lennard-Jones (LJ) potential, is the computational expense of the simulations required to calculate macroscopic physical properties. This limits the size of the training set and often confines optimization to a local parameter region [7].

To overcome this, a multi-fidelity optimization technique using Gaussian process surrogate modeling has been developed. The workflow, as illustrated below, involves building inexpensive models of physical properties as a function of LJ parameters, which allows for rapid evaluation of objective functions and accelerates global searches over the parameter space [7].

This iterative framework performs global optimization at the surrogate level, followed by validation at the simulation level and surrogate refinement. This approach has been demonstrated to find improved parameter sets for the OpenFF 1.0.0 "Parsley" force field by searching more broadly and escaping local minima, a task difficult to achieve with purely simulation-based optimization [7].

Surrogate models represent a paradigm shift in computational science and engineering. By acting as fast and accurate approximations of complex systems, they decisively address the critical bottleneck of computational cost. As detailed in this guide, a diverse arsenal of surrogate modeling techniques—from Polynomial Chaos Expansions and Gaussian Processes to Artificial Neural Networks—is available, each with distinct strengths suited to particular challenges in chemistry and drug development. The rigorous, iterative methodology for their development and validation ensures reliability. The integration of these models, particularly within multi-fidelity frameworks, empowers researchers to undertake previously intractable tasks, such as the global optimization of force field parameters against large training sets of physical properties. The adoption of surrogate modeling is thus not merely a convenience but a strategic imperative for accelerating innovation and enhancing the robustness of computational research.

The Potential Energy Surface (PES) is a fundamental concept in theoretical chemistry that maps the energy of a molecular system as a function of its nuclear coordinates. This technical guide explores the intricate topology of PESs, with a particular focus on the critical challenge of locating the global minimum—the most stable molecular configuration. Framed within the context of modern computational research, this whitepaper details how surrogate modeling and advanced global optimization techniques are revolutionizing our ability to navigate these complex, high-dimensional landscapes. We provide a comprehensive analysis of PES stationary points, systematic methodologies for their exploration, and data-driven optimization protocols that are essential for accelerating discoveries in chemical research and drug development.

A Potential Energy Surface (PES) describes the potential energy of a system of atoms, typically a molecule or a collection of molecules, in terms of certain parameters, which are normally the positions of the atoms [12]. The PES can be visualized as a multidimensional landscape, where the "height" corresponds to the system's energy. For a system with only one geometric parameter, such as the bond length in a diatomic molecule, this is represented as a two-dimensional potential energy curve. The internuclear distance at which the potential energy minimum occurs defines the equilibrium bond length [13].

For polyatomic molecules involving N atoms, the PES becomes a high-dimensional hypersurface. The full dimensionality of a PES is 3N-6 (or 3N-5 for linear molecules), after subtracting translational and rotational degrees of freedom [13]. This high-dimensionality makes complete visualization impossible, and chemists often use two- or three-dimensional slices to represent the energy as a function of one or two key geometric parameters, such as bond lengths or dihedral angles [14].

The PES is a direct consequence of the Born-Oppenheimer approximation, which allows for the separation of electronic and nuclear motion. This approximation makes the concept of molecular geometry meaningful and enables the calculation of energy for any given arrangement of nuclei [14]. The PES concept finds critical application in fields such as chemistry, biochemistry, and pharmacology, enabling the theoretical exploration of molecular properties, the prediction of reaction pathways, and the determination of the most stable conformations of molecular entities [12].

Stationary Points on the PES: Minima, Saddle Points, and the Global Minimum

The topology of a PES is characterized by its stationary points, where the first derivative of the energy with respect to all geometric coordinates is zero [14]. A marble placed on a stationary point would remain balanced. These points are mathematically defined as points where ∂E/∂qᵢ = 0 for all geometric parameters qᵢ [14].

Types of Stationary Points

Stationary points are classified according to the second derivatives of the energy (the Hessian matrix) and represent fundamentally different molecular structures.

- Local Minima: These points correspond to the geometries of stable chemical species with a finite lifetime [12]. At a local minimum, any small change in the geometry increases the energy [14]. A local minimum is a minimum in all directions [14]. A molecule situated at a local minimum will vibrate incessantly but remains in a metastable state.

- Global Minimum: This is the lowest-energy minimum on the entire PES [14]. It represents the most thermodynamically stable configuration of the system. For example, in a protein folding landscape, the global minimum corresponds to the native, functional fold of the protein [12]. Locating the global minimum is a central challenge in computational chemistry and drug design, as it defines the preferred structure of a molecule.

- Saddle Points (Transition States): These first-order saddle points are stationary points that represent the maximum along the lowest energy pathway (the reaction coordinate) connecting two minima, but are a minimum in all other perpendicular directions [12] [14]. This gives them a saddle-shaped character. They correspond to transition states in a chemical reaction—the highest-energy point on the reaction coordinate and the structure that exists only for an instant during the transformation from reactant to product [12].

Table 1: Characteristics of Key Stationary Points on a PES

| Stationary Point | First Derivative (Gradient) | Second Derivative (Curvature) | Physical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Local Minimum | Zero | Positive in all directions | Metastable molecular structure |

| Global Minimum | Zero | Positive in all directions | Most stable molecular structure |

| Saddle Point (Transition State) | Zero | Negative along reaction coordinate; Positive in all other directions | Activated complex for a chemical reaction |

Visualizing the PES Landscape

The following diagram illustrates the key topological features of a PES, including the global minimum, local minima, and the transition state connecting two minima.

The Central Challenge: Locating the Global Minimum

Finding the global minimum on a PES is a daunting global optimization problem. The number of local minima on a PES grows exponentially with the number of atoms in the system. For example, even a relatively small cluster of atoms or a modest-sized peptide can have a number of minima that is astronomically large [15]. This "combinatorial explosion" makes an exhaustive search for the global minimum computationally intractable for all but the smallest systems.

The relaxation dynamics towards the global minimum are highly dependent on the system's energy. Studies on model PESs have shown a characteristic "folding time" (the time required for the global minimum to reach a high probability of occupation) that exhibits a clear minimum at a specific energy level [15]. At low energies, the folding time increases because it is difficult to overcome barriers on the PES. At high energies, the driving force towards the global minimum is diminished, also increasing the folding time [15]. This creates an "energy window" for optimal exploration, a principle leveraged in advanced annealing techniques.

This global minimum problem is paramount in drug design. The biological activity of a small molecule drug is intimately tied to its three-dimensional conformation. Docking studies and pharmacophore modeling rely on accurately predicting the lowest-energy conformations of ligands. Failure to identify the true global minimum can lead to incorrect predictions of binding affinity and selectivity, derailing the drug discovery process.

Methodologies for Exploring the PES and Global Optimization

Computational Methods for PES Construction

Calculating the energy for a given atomic arrangement is the foundational step in mapping a PES. The choice of method involves a trade-off between computational cost and accuracy.

- Ab Initio Quantum Chemistry Methods: These methods, such as density functional theory (DFT) and coupled cluster theory, solve the electronic Schrödinger equation from first principles. They are highly accurate but can be prohibitively expensive for large systems or for generating the thousands of data points needed for a fine-grained PES [16].

- Semi-Empirical Methods and Force Fields: These approaches use simplified quantum models or classical potentials (molecular mechanics) to calculate energy. They are computationally cheap and essential for studying large systems like proteins, but their accuracy is lower than that of ab initio methods [14].

- Interpolation and Surrogate Models: To address the cost of high-level calculations, a reduced set of high-fidelity points can be computed and a cheaper surrogate model can be used for interpolation, such as Shepard interpolation [12] or machine learning models, to fill in the gaps and create a continuous surface.

Experimental Protocol for Surrogate-Based PES Optimization

Surrogate-based optimization is a powerful framework for navigating the PES while minimizing calls to expensive computational models (e.g., ab initio calculations). The following workflow diagram and detailed protocol outline this data-driven approach.

Protocol Details:

Initial Sampling (Design of Experiments):

- Objective: Select an initial set of molecular geometries (nuclear coordinates) to evaluate with the high-fidelity model.

- Method: Use space-filling designs like Latin Hypercube Sampling (LHS) or Sobol sequences to ensure good coverage of the configuration space within the defined bounds for each geometric coordinate [2].

- Data Output: A vector, r, for each sample, representing the atomic positions in Cartesian coordinates or internal coordinates (bond lengths, angles, dihedrals) [12] [13].

High-Fidelity Energy Calculations:

- Objective: Generate accurate training data for the surrogate model.

- Method: Perform ab initio (e.g., DFT) or high-level composite method calculations on each sampled geometry to obtain the potential energy, E(r). This is the most computationally expensive step in the workflow [16] [2].

- Data Output: A dataset of input geometries and their corresponding high-fidelity energies:

{r_i, E_HF(r_i)}.

Surrogate Model Training & Validation:

- Objective: Create a cheap-to-evaluate algebraic function that approximates the high-fidelity PES.

- Method: Train a machine learning model on the

{r_i, E_HF(r_i)}dataset. Common models include: - Validation: The model's accuracy is tested on a held-out validation set not used during training, typically using metrics like Mean Absolute Error (MAE) [2].

Global Optimization on Surrogate Model:

- Objective: Locate the global minimum of the surrogate PES.

- Method: Employ deterministic global optimization solvers (e.g., branch-and-bound) or hybrid metaheuristics. Because the surrogate is an algebraic model, its derivatives can often be calculated analytically, facilitating efficient optimization [2]. Tools like the Optimization and Machine Learning Toolkit (OMLT) can translate trained ML models into optimization-oriented formats [2].

- Output: A candidate geometry, r_candidate, for the global minimum.

Adaptive Sampling & Model Refinement:

- Objective: Iteratively improve the surrogate model's accuracy, especially in promising regions of the PES.

- Method: The candidate r_candidate is evaluated with the high-fidelity model. This new data point is added to the training set. Sampling can be guided by the surrogate's predictions and its uncertainty (e.g., sampling where the predicted energy is low or where uncertainty is high) [2]. This iterative loop continues until convergence criteria are met (e.g., the global minimum is confirmed, or a computational budget is exhausted).

Advanced Techniques: Hybrid and Multi-Fidelity Modeling

A key advancement is the development of hybrid models or multi-fidelity surrogate models (MFSMs). These models integrate a small set of expensive high-fidelity data (e.g., from ab initio calculations) with a larger set of inexpensive low-fidelity data (e.g., from semi-empirical methods or cheap force fields) [2]. The MFSM uses a composite structure to learn a correction to the low-fidelity model, thereby achieving high accuracy at a lower computational cost than a model built from high-fidelity data alone [2]. Research has shown that hybrid modeling improves surrogate robustness and reduces variability in optimization results, often requiring fewer high-fidelity samples [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key computational tools and methodologies essential for modern PES exploration and global optimization.

Table 2: Essential Research Tools for PES Exploration and Global Optimization

| Tool / Method | Type | Function in PES Research |

|---|---|---|

| Ab Initio / DFT Codes (e.g., Gaussian, ORCA) | Computational Chemistry Software | Provides high-fidelity energy and derivative calculations for specific molecular geometries. |

| Neural Networks (NNs) | Machine Learning Model | Acts as a flexible, non-linear surrogate model to approximate the entire PES from sample data [16] [2]. |

| Gaussian Process Regression (GPR) | Machine Learning Model | Serves as a surrogate model that provides predictions with uncertainty estimates, useful for adaptive sampling [16]. |

| Hybrid Modeling (MFSM) | Modeling Framework | Combines data of different fidelities to create a robust and computationally efficient surrogate PES [2]. |

| Optimization & Machine Learning Toolkit (OMLT) | Software Library | Translates trained machine learning models (e.g., NNs) into formats compatible with mathematical optimization solvers [2]. |

| Adaptive Sampling Algorithms (e.g., DDSBB) | Optimization Algorithm | Guides the iterative selection of new sample points to refine the surrogate model and efficiently locate the global minimum [2]. |

The Potential Energy Surface is the conceptual bedrock for understanding molecular structure, stability, and reactivity. Navigating this high-dimensional landscape to find the global minimum remains one of the most challenging problems in computational chemistry. The emergence of data-driven strategies, particularly surrogate-based optimization and hybrid modeling, represents a paradigm shift. These techniques leverage machine learning to create accurate, computationally efficient maps of the PES, enabling a more thorough and rapid exploration for drug discovery professionals and researchers. By integrating adaptive sampling and multi-fidelity data, these modern approaches provide a powerful and scalable framework for conquering the complexity of molecular energy landscapes, ultimately accelerating the design of new molecules, materials, and therapeutics.

Global optimization is a critical capability in computational chemistry and drug discovery, where researchers must often find the best possible solutions in complex, multidimensional landscapes. These landscapes are frequently nonconvex, featuring multiple local optima that can trap conventional optimization algorithms [17]. The two primary philosophies for tackling these problems are deterministic and stochastic approaches, each with distinct theoretical foundations, performance characteristics, and application domains.

Deterministic methods provide mathematical guarantees of convergence to the global optimum but often at computational costs that limit their applicability to smaller problems. In contrast, stochastic methods employ probabilistic strategies to explore the search space more broadly, offering better scalability but without absolute guarantees of global optimality [17] [18]. This technical guide examines both paradigms within the context of modern chemical research, with particular emphasis on emerging hybrid approaches and surrogate-based methods that are expanding the frontiers of what is computationally feasible in molecular design and process optimization.

Theoretical Foundations and Comparative Analysis

Core Principles of Deterministic Methods

Deterministic global optimization algorithms provide a mathematical guarantee of convergence to the globally optimal solution through rigorous bounding operations and spatial branch-and-bound techniques. These methods systematically partition the feasible region and eliminate suboptimal regions using convex relaxations that provide valid lower bounds for minimization problems [17] [19].

Key deterministic approaches include the αBB (alpha-Branch-and-Bound) algorithm, which constructs convex underestimators for twice-differentiable functions, and interval analysis methods that propagate bounds through mathematical operations to identify regions containing global optima [17]. The Global Optimization Algorithm (GOP) decomposes problems through primal and relational partitioning, making it particularly effective for certain classes of nonconvex nonlinear programs [17]. These methods excel in problems with well-defined mathematical structure but face the "curse of dimensionality" as problem size increases.

Fundamental Mechanisms of Stochastic Methods

Stochastic optimization methods employ randomized sampling and probability-driven search strategies to explore complex solution spaces. Unlike their deterministic counterparts, these approaches do not offer mathematical guarantees of global optimality but typically exhibit superior scalability to larger, more complex problems [17] [18].

Major stochastic paradigms include genetic algorithms inspired by natural selection, which maintain populations of candidate solutions and apply mutation, crossover, and selection operations [17]. Simulated annealing models the physical annealing process of solids, allowing probabilistic acceptance of worse solutions to escape local minima [17]. Evolution strategies focus on self-adapting strategy parameters during the search process, while Bayesian optimization constructs probabilistic surrogate models to guide sample-efficient exploration of expensive black-box functions [4] [20].

Comparative Performance Analysis

Table 1: Comparative characteristics of deterministic and stochastic global optimization methods

| Characteristic | Deterministic Methods | Stochastic Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Optimality Guarantee | Mathematical guarantee of global optimality | No guarantee of global optimality; probability of success increases with computational effort |

| Computational Complexity | Exponential in worst case; applicable mainly to small problems | Polynomial complexity; applicable to large-scale problems |

| Handling of Constraints | Strong theoretical foundations for nonlinear equality constraints | Inefficient when many nonlinear equality constraints are present |

| Implementation Complexity | Algorithmically complex; requires problem structure exploitation | Conceptually simpler; often implemented as general-purpose solvers |

| Scalability | Limited to small-scale problems | Suitable for large-scale problems |

| Typical Applications | Process design with few variables, molecular conformation with small molecules | Drug design, force field parameterization, large molecular systems |

The fundamental trade-off between these approaches is clear: deterministic methods provide certainty at the cost of scalability, while stochastic methods offer scalability without certainty [17]. This distinction profoundly influences their application domains within chemical research, with deterministic methods favored for well-structured problems of limited size, and stochastic methods preferred for complex, high-dimensional molecular design problems.

Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Determinative Branch-and-Bound Implementation

The αBB algorithm represents a sophisticated deterministic approach for twice-differentiable functions. The implementation follows a rigorous multi-step protocol:

Initialization: Define the original problem and initial search space bounds. For chemical process optimization, this typically involves defining temperature, pressure, and flow rate windows [17].

Convex Underestimation: Construct a convex lower bounding function through the addition of a quadratic term: L(x) = f(x) + α∑(xi - xi^L)(xi^U - xi), where α is carefully selected to ensure convexity [17].

Partitioning: Implement a branching strategy that divides the current region into subregions, typically using bisection along the longest dimension.

Bounding: Solve the convex relaxed problem in each subregion to obtain lower bounds. In chemical process design, this might involve solving simplified thermodynamic models [17].

Pruning: Eliminate subregions whose lower bounds exceed the current best upper bound.

Termination: The algorithm concludes when the gap between the global upper bound and the best lower bound falls below a specified tolerance, providing a mathematically certified ε-global optimum.

Stochastic Optimization with Surrogate Modeling

Modern stochastic approaches frequently employ machine learning surrogates to accelerate the exploration of expensive energy landscapes. The following protocol, adapted from recent computational materials research, illustrates this paradigm [21]:

Initialization:

- Input: SMILES string representing the adsorbate and relaxed geometry of the clean surface

- Generate initial gas-phase molecular geometry using Merck Molecular Force Field (MMFF)

- Define Hookean constraints to maintain molecular identity during simulation

Initial Sampling:

- Randomly place the adsorbate onto the catalyst surface

- Perform initial DFT calculation to obtain reference energy and forces

- Use this single configuration as the initial training set for the Gaussian Approximation Potential (GAP)

Iterative Training and Exploration:

- Perform minima hopping (MH) simulations on the current GAP surrogate

- Select diverse configurations using Farthest Point Sampling (FPS) from both MD snapshots and local minima

- Compute DFT single-point energies for selected structures

- Augment training set and retrain GAP model

- Repeat until convergence in predicted low-energy structures

Production and Validation:

- Execute extensive parallel MH simulations using the converged GAP

- Cluster resulting minima using Kernel PCA and k-means clustering

- Perform final local DFT relaxations on representative structures

- Verify global minimum stability through multiple independent runs

This protocol actively learns a potential energy surface with minimal human intervention, typically requiring 5-10 iterations with 5 DFT calculations per iteration to achieve convergence for medium-sized organic molecules on metal surfaces [21].

Bayesian Optimization for Drug Discovery

Bayesian optimization has emerged as a powerful stochastic approach for black-box optimization in pharmaceutical research [4]. The standard implementation comprises:

Prior Selection: Choose a Gaussian process prior with appropriate kernel function. The Matérn kernel is commonly preferred for chemical optimization problems.

Initial Design: Select an initial experimental design, typically using Latin Hypercube Sampling (LHS) or random sampling within defined molecular property spaces.

Sequential Optimization Loop:

- Update the Gaussian process posterior using all available function evaluations

- Optimize an acquisition function (Expected Improvement, Upper Confidence Bound, or Probability of Improvement) to select the next evaluation point

- Evaluate the objective function at the proposed point (e.g., synthesize and test compound)

- Augment data set with new observation

Termination: Continue until computational budget exhausted or convergence criteria met.

This framework is particularly valuable in drug discovery for balancing exploration of novel chemical space with exploitation of promising regions, efficiently navigating high-dimensional molecular design problems where quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) models define the objective landscape [4] [22].

Visualization of Methodologies

Diagram 1: Deterministic branch-and-bound optimization workflow

Diagram 2: Stochastic surrogate-assisted optimization workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential computational tools for global optimization in chemical research

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gaussian Process Regression | Statistical Model | Surrogate modeling with uncertainty quantification | Bayesian optimization for molecular design [4] [21] |

| αBB Algorithm | Deterministic Solver | Global optimization with guaranteed convergence | Small-scale process design and molecular conformation [17] |

| Gillespie Algorithm | Stochastic Simulator | Exact simulation of chemical master equation | Mesoscopic biochemical systems with low copy numbers [18] [23] |

| Genetic Algorithms | Stochastic Optimizer | Population-based evolutionary search | Force field parameterization and molecular docking [17] [24] |

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) | First-Principles Method | High-fidelity energy evaluation | Ground truth data for surrogate training [21] |

| Gaussian Approximation Potentials (GAP) | Machine Learning Potential | Data-driven interatomic potentials | Accelerated structure optimization [21] |

Applications in Chemistry and Drug Discovery

Force Field Parameter Optimization

The development of accurate force fields represents a fundamental challenge in computational chemistry, where parameters must be optimized to reproduce experimental observables or high-fidelity quantum mechanical data. Recent work has demonstrated the effectiveness of multi-fidelity global optimization using Gaussian process surrogate models to accelerate this process [7].

In this approach, surrogate models learn the relationship between Lennard-Jones parameters and macroscopic physical properties, enabling rapid screening of parameter space. The method employs an iterative framework performing global optimization at the surrogate level, followed by validation with molecular dynamics simulations and surrogate refinement [7]. This strategy has been successfully applied to refit subsets of LJ parameters for the OpenFF 1.0.0 "Parsley" force field against training sets containing up to 195 physical property targets, demonstrating improved performance over simulation-only optimization by escaping local minima and searching parameter space more broadly [7].

Molecular Structure and Adsorbate Geometry Optimization

Identifying global minimum configurations for molecular adsorbates on catalyst surfaces constitutes a challenging optimization problem due to the multitude of possible binding motifs and complex potential energy surfaces. Traditional "brute-intuition" approaches, where researchers manually construct plausible initial geometries, introduce significant bias and often miss optimal configurations [21].

Machine-learning driven global optimization protocols address this limitation by training surrogate potentials on-the-fly during stochastic structure searches. These approaches have been successfully applied to diverse adsorbates on transition metal surfaces, systematically exploring configuration space with minimal human intervention [21]. The method has proven particularly valuable for larger, flexible reaction intermediates in syngas conversion, where multidentate binding geometries and internal flexibility create particularly complex energy landscapes [21].

Multi-objective Optimization in Drug Discovery

Drug discovery inherently involves balancing multiple, often competing objectives including potency, selectivity, solubility, and metabolic stability. Multi-objective optimization strategies have emerged as powerful approaches for identifying Pareto-optimal compound series where improvements in one property cannot be achieved without degrading another [22].

These methods have been successfully applied to diverse challenges including drug library design, substructure mining, quantitative structure-activity relationship modeling, and ranking of docking poses [22]. By framing drug discovery as a multi-objective problem, researchers can systematically explore trade-offs between absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) properties while maintaining target engagement, ultimately accelerating the identification of viable clinical candidates [22].

The dichotomy between deterministic and stochastic global optimization methods represents a fundamental trade-off between computational certainty and practical scalability in chemical research. Deterministic approaches provide mathematical guarantees of global optimality through rigorous bounding operations but face severe limitations when applied to large-scale problems. Stochastic methods offer greater scalability through probabilistic exploration but cannot provide absolute guarantees of global convergence.

Contemporary research increasingly focuses on hybrid strategies that leverage the strengths of both paradigms. The integration of machine learning surrogate models with stochastic search frameworks has been particularly transformative, enabling efficient navigation of complex molecular energy landscapes that were previously computationally intractable. These approaches are proving invaluable across diverse domains including force field development, catalyst design, and pharmaceutical optimization.

As computational methodologies continue to evolve, the distinction between deterministic and stochastic paradigms may gradually blur through increasingly sophisticated hybrid algorithms. However, the fundamental understanding of both approaches remains essential for selecting appropriate strategies for specific chemical optimization challenges and for developing the next generation of global optimization tools.

Surrogate-Based Global Optimization (SBGO) has emerged as a crucial methodology for tackling computationally expensive black-box problems in chemical engineering and drug discovery research. This technical guide examines the three fundamental components of SBGO frameworks—design of experiments, surrogate model building, and infill criteria—within the context of chemistry research applications. By implementing adaptive sampling techniques and ensemble modeling approaches, researchers can significantly reduce the number of expensive function evaluations required for optimization tasks, such as reaction condition optimization and molecular design. This review synthesizes current methodologies and provides structured protocols for implementing SBGO in chemical research settings, offering researchers a comprehensive framework for optimizing complex experimental processes while managing computational resources efficiently.

Surrogate-Based Global Optimization (SBGO) represents a paradigm shift for researchers dealing with computationally intensive problems where a single function evaluation might require hours or even days of computational time, such as in molecular dynamics simulations or quantum chemistry calculations. SBGO methods address this challenge by constructing computationally inexpensive surrogate models that approximate the behavior of expensive black-box functions, then using these models to guide the optimization process toward promising regions of the design space [25]. The fundamental premise of SBGO is the iterative refinement of these surrogate models through strategically selected new sample points, balancing global exploration of the design space with local exploitation of promising regions [26].

In chemical research, SBGO finds application across diverse domains including reaction optimization, molecular design, process parameter tuning, and catalyst discovery. For instance, when optimizing reaction conditions for pharmaceutical synthesis, each experimental trial might represent significant time and resource investment. SBGO frameworks mitigate these costs by building predictive models from initial experiments, then suggesting the most informative subsequent experiments to perform [25] [26]. The sequential nature of SBGO—cycling between model building and targeted sampling—makes it particularly valuable for high-dimensional optimization problems common in chemical applications where traditional experimental design methods become prohibitively expensive.

Fundamental Components of SBGO Frameworks

Design of Experiments for Initial Sampling

The initial design of experiments (DOE) establishes the foundation for effective surrogate modeling by selecting a set of sample points that efficiently cover the design space while minimizing the number of expensive function evaluations. For chemical applications, careful DOE selection is critical as it determines how well the initial surrogate model will capture the underlying response surface, which might represent reaction yield, purity, or other performance metrics as a function of input parameters such as temperature, concentration, pH, or catalyst loading [25].

Table 1: Design of Experiments Methods for Initial Sampling in SBGO

| Method | Key Characteristics | Chemical Research Applications | Sample Size Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|

| Latin Hypercube Sampling (LHS) | Space-filling properties, probabilistic stratification | Preliminary screening of factors, high-dimensional problems | 5-10 times the number of dimensions [25] |

| Optimal Latin Hypercube | Enhanced space-filling through optimization | Resource-intensive experiments, constrained design spaces | Similar to LHS but with improved coverage [26] |

| Fractional Factorial Design | Reduced experimental runs, aliasing of effects | Factor screening in early-stage research | 2^(k-p) where k=factors, p=reduction [25] |

| Central Composite Design | Estimation of curvature, response surface modeling | Process optimization, parameter tuning | 2^k + 2k + center points [25] |

| Uniform Design | Uniform dispersion over experimental domain | Robust parameter design, computer experiments | Flexible, often similar to LHS [25] |

For chemical applications involving constrained design spaces (e.g., compositional constraints in mixture designs or physiochemical feasibility limits), advanced DOE methods incorporating feasibility constraints are essential. These methods ensure that initial sampling points satisfy all necessary constraints while maintaining good space-filling properties, thereby establishing a robust foundation for subsequent surrogate modeling steps [25].

Surrogate Modeling Techniques

Surrogate modeling forms the computational core of SBGO frameworks, providing inexpensive approximations of expensive computational or experimental processes. The selection of an appropriate surrogate modeling technique depends on the characteristics of the underlying chemical system, including nonlinearity, smoothness, dimensionality, and the presence of noise in experimental measurements [25].

Table 2: Surrogate Modeling Techniques in SBGO

| Model Type | Mathematical Foundation | Advantages | Limitations | Chemical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kriging/Gaussian Process | Spatial correlation, Bayesian framework | Uncertainty quantification, proven convergence | Cubic computational complexity | Catalyst design, molecular property prediction [25] [26] |

| Radial Basis Functions (RBF) | Linear combination of basis functions | Handles non-smooth functions, relatively simple | Choice of basis function affects performance | Reaction optimization, computational chemistry [26] |

| Polynomial Response Surfaces | Polynomial regression | Computational efficiency, simplicity | Poor for highly nonlinear systems | Preliminary screening, process characterization [25] |

| Artificial Neural Networks | Network of connected neurons | Handles high dimensionality, strong flexibility | Large data requirements, complex training | Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationships (QSAR) [25] |

| Support Vector Regression | Statistical learning theory | Good generalization, handles nonlinearity | Parameter sensitivity | Chemical process optimization [25] |

In chemical research practice, ensemble modeling approaches that combine multiple surrogate models have demonstrated enhanced robustness and predictive accuracy compared to individual models. Methods such as weighted average ensembles dynamically assign weights to different models based on their local predictive performance, providing more reliable approximations for guiding the optimization process [25]. This approach is particularly valuable in chemical applications where the characteristics of the response surface may vary across different regions of the design space.

Diagram 1: SBGO Iterative Workflow. The process cycles between surrogate model building and strategic point selection until convergence.

Infill Sampling Criteria

Infill sampling criteria determine which new points should be evaluated using the expensive function to iteratively improve the surrogate model and progress toward the global optimum. These criteria balance the competing objectives of global exploration (sampling in regions with high uncertainty) and local exploitation (sampling in regions with promising predicted values) [26].

The Expected Improvement (EI) criterion represents one of the most widely adopted infill methods, simultaneously addressing exploration and exploitation by calculating the expected value of improvement over the current best function value. For chemical applications where multiple objectives often must be balanced (e.g., maximizing yield while minimizing impurities or cost), multi-objective extensions of EI have been developed that compute improvement based on Pareto dominance relationships [25].

Probability of Improvement (PI) focuses exclusively on the probability that a new point will outperform the current best solution, making it primarily an exploitation-focused criterion. In contrast, the Weighted Minimum Distance (WD) criterion emphasizes exploration by considering both the response values and the distance to existing samples, ensuring that new points are selected from sparsely sampled regions of the design space [26].

Advanced adaptive infill strategies that dynamically switch between different criteria based on search progress have demonstrated superior performance compared to single-criterion approaches. For instance, an algorithm might initially prioritize exploration-focused criteria to broadly characterize the design space, then gradually shift toward exploitation-focused criteria to refine the solution once promising regions have been identified [26].

Diagram 2: Adaptive Infill Criterion Selection. The strategy dynamically balances exploration and exploitation based on search progress.

Advanced SBGO Methodologies

Constrained Optimization Formulations

Real-world chemical optimization problems invariably involve multiple constraints, including material balance limitations, physicochemical property boundaries, safety restrictions, and economic considerations. SBGO frameworks address these challenges through constraint-handling mechanisms such as penalty functions, which transform constrained problems into unconstrained ones by adding penalty terms to the objective function that activate when constraints are violated [26].

For problems with computationally expensive constraint functions, separate surrogate models can be constructed for each constraint, enabling prediction of constraint satisfaction without additional expensive evaluations. The Expected Violation (EV) criterion extends the EI concept to constrained problems by considering both the predicted improvement in objective function and the probability of constraint satisfaction when selecting new infill points [25].

Space Reduction Techniques

As optimization progresses, design space reduction techniques progressively focus the search on promising regions, enhancing computational efficiency for high-dimensional chemical problems. Fuzzy clustering-based approaches automatically identify promising regions by grouping sample points with similar performance characteristics, then constructing local surrogate models within each cluster [25].

Multi-Start Space Reduction (MSSR) combines global search with progressive space reduction by maintaining multiple candidate regions and iteratively focusing on the most promising ones based on surrogate model predictions and actual function evaluations. This approach is particularly valuable for chemical problems with multiple local optima, as it preserves diversity in the search while improving efficiency [25].

Experimental Protocols and Implementation

SBGO Implementation Protocol for Chemical Applications

Implementing SBGO for chemical research requires careful attention to both computational and experimental considerations. The following protocol provides a structured methodology for applying SBGO to chemical optimization problems:

Problem Formulation Phase: Clearly define the objective function (e.g., reaction yield, product purity, process efficiency), identify all decision variables (e.g., temperature, concentration, residence time) with their bounds, and specify all constraints (e.g., material balances, safety limits, equipment capabilities). Document any known structural characteristics of the system, such as expected nonlinearities or known local optima.

Initial Experimental Design: Select an appropriate DOE method based on problem characteristics. For problems with limited prior knowledge and moderate dimensionality (≤10 variables), Optimal Latin Hypercube designs typically provide good space-filling properties. For higher-dimensional problems or when computational resources are severely limited, fractional factorial designs may be more appropriate. The recommended sample size for initial design is 5-10 times the number of decision variables [25].

Surrogate Model Selection and Validation: Construct multiple surrogate models using the initial experimental data. Apply cross-validation techniques to assess predictive accuracy, calculating statistics such as Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) and R² values. For chemical applications with limited data, leave-one-out cross-validation is particularly valuable. Select the most appropriate model type based on validation metrics, or implement an ensemble approach that combines multiple models [25].

Iterative Optimization Phase: Implement the following iterative process until convergence or exhaustion of the experimental budget:

- Apply the selected infill criterion to identify promising candidate points

- Evaluate candidate points using the expensive function (experimental or computational)

- Update the surrogate model with new data

- Apply convergence criteria (e.g., minimal improvement over multiple iterations, minimal model uncertainty in promising regions, or exhaustion of experimental budget)

Validation and Implementation: Validate the identified optimum through confirmatory experiments or high-fidelity simulations. Document the final model and optimization trajectory for future reference and potential model reuse.

Research Reagent Solutions and Computational Tools

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for SBGO Implementation

| Tool/Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in SBGO Workflow | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| DOE Software Platforms | JMP, Design-Expert, R (DoE.base) | Initial experimental design generation | Compatibility with existing laboratory information systems |

| Surrogate Modeling Libraries | SUMO Toolbox, SMT (Surrogate Modeling Toolbox) | Construction of approximation models | Integration with computational chemistry software |

| Optimization Frameworks | DAKOTA, Optimus, MATLAB Global Optimization Toolbox | Implementation of infill criteria and optimization algorithms | Scalability to problem dimensionality |

| Chemical Simulation Software | Gaussian, COMSOL, Aspen Plus | Expensive function evaluations in silico | Computational resource requirements |

| Laboratory Automation Systems | HPLC, robotic fluid handling systems | Automated experimental execution for physical evaluations | Standardization of experimental protocols |

SBGO represents a powerful methodology for addressing computationally expensive optimization problems in chemical research and drug development. By integrating strategic design of experiments, sophisticated surrogate modeling, and adaptive infill criteria, SBGO frameworks enable efficient navigation of complex design spaces while minimizing the number of expensive function evaluations required. The continued development of SBGO methodologies—particularly in areas of multi-objective optimization, high-dimensional problems, and integration with experimental automation—promises to further enhance its utility for chemical applications. As computational resources expand and machine learning techniques advance, SBGO is positioned to become an increasingly indispensable tool in the chemical researcher's toolkit, enabling more efficient exploration of complex chemical systems and accelerating the discovery and development of new molecules and processes.

A Practical Guide to Optimization Algorithms and Their Chemical Applications

The pursuit of novel chemical compounds and pharmaceuticals represents one of the most computationally challenging domains in scientific research. Chemistry and drug discovery inherently involve navigating complex, high-dimensional search spaces with numerous local optima—from molecular conformation analysis and protein folding to quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) modeling and reaction optimization. Global optimization techniques provide the mathematical foundation for exploring these vast solution spaces where traditional gradient-based methods often fail due to their propensity to become trapped in suboptimal regions. Among these techniques, three algorithms stand out as traditional workhorses: Genetic Algorithms (GAs), Simulated Annealing (SA), and Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO).

These metaheuristics have demonstrated remarkable efficacy in addressing challenging optimization problems across chemical domains without requiring derivative information. Their ability to handle non-differentiable, multi-modal, and noisy objective functions makes them particularly suitable for chemical applications where energy landscapes are often discontinuous or poorly understood. Within the broader context of surrogate and global optimization frameworks, these algorithms serve as essential components in hybrid approaches and adaptive sampling strategies, enabling researchers to balance exploration of the global search space with exploitation of promising regions.

This technical guide examines the fundamental principles, implementation methodologies, and chemical applications of these three established optimization workhorses. By providing detailed protocols, comparative analysis, and practical implementation guidelines, we aim to equip chemistry researchers with the knowledge necessary to select and apply appropriate optimization strategies to their specific research challenges in molecular design, reaction optimization, and drug discovery pipelines.

Fundamental Principles and Mechanisms

Genetic Algorithms (GAs)

Inspired by Darwinian evolution, Genetic Algorithms (GAs) operate on a population of candidate solutions through selection, crossover, and mutation operations. The algorithm encodes parameters into chromosomes and evolves them over generations toward increasingly optimal configurations. GAs are particularly valuable for chemical applications because they can efficiently explore complex, non-convex search spaces common in molecular design and conformational analysis [27].

The evolutionary process in GAs begins with initialization of a random population, followed by fitness evaluation of each individual. Selection mechanisms such as tournament or roulette wheel selection then prioritize fitter individuals for reproduction. The crossover operation combines genetic material from parent chromosomes to produce offspring, while mutation introduces random changes to maintain population diversity. This iterative process continues until convergence criteria are met, yielding highly optimized solutions to the target problem [27].

For chemistry researchers, GAs offer distinct advantages including their global search capability that helps avoid local minima in complex energy landscapes, model-agnostic nature allowing application to diverse chemical problems, no gradient requirement making them suitable for non-differentiable objective functions, and parallelizability enabling efficient distribution of fitness evaluations across computing resources [27].

Simulated Annealing (SA)