Surrogate Optimization for Analytical Chemistry Instrumentation: A Machine Learning-Driven Paradigm

This article explores the transformative role of surrogate optimization in enhancing analytical chemistry instrumentation, a critical need for researchers and drug development professionals facing costly and time-consuming experimental processes.

Surrogate Optimization for Analytical Chemistry Instrumentation: A Machine Learning-Driven Paradigm

Abstract

This article explores the transformative role of surrogate optimization in enhancing analytical chemistry instrumentation, a critical need for researchers and drug development professionals facing costly and time-consuming experimental processes. We first establish the foundational principles of surrogate modeling as a machine learning-powered alternative to traditional trial-and-error methods. The discussion then progresses to methodological implementations, showcasing successful applications in chromatography and mass spectrometry that significantly reduce development time and material costs. A dedicated troubleshooting section provides strategies for overcoming common challenges like data scarcity and algorithm selection. Finally, we present a comparative analysis of different surrogate modeling techniques, validating their performance through real-world case studies and established benchmarks. This comprehensive guide aims to equip scientists with the knowledge to leverage surrogate optimization for accelerated and more efficient analytical method development.

What is Surrogate Optimization and Why is it Revolutionizing Analytical Chemistry?

In the context of analytical chemistry instrumentation, a surrogate model is a machine learning-based approximation of a complex, computationally expensive, or analytically intractable system. It serves as a fast, data-driven emulator for predicting the behavior of a scientific instrument or process without executing the full, resource-intensive simulation or experimental procedure [1]. In chromatographic method development, for instance, these models enable more efficient experimentation, guide optimization strategies, and support predictive analysis, offering significant advantages over traditional methods like response surface modeling [1]. The core value of a surrogate lies in its ability to make optimization processes—which would otherwise be prohibitively slow or expensive—feasible and efficient. This approach is not limited to chemistry; it is a powerful tool in diverse fields such as quantum networking [2] and reservoir simulation [3], where it helps optimize systems based on intricate numerical simulations.

Comparative Analysis of Surrogate Model Types

The selection of an appropriate surrogate model depends on the specific problem, data availability, and computational constraints. The following table summarizes key types of surrogate models and their applicability in scientific domains.

Table 1: Comparison of Surrogate Model Types and Applications

| Model Type | Key Characteristics | Best-Suited Problems | Performance & Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Random Forest (RF) [2] | Explainable, computationally efficient, handles mixed data types, low risk of overfitting. | High-dimensional problems (up to 100 variables) [2], non-linear relationships. | Demonstrated high efficiency in quantum network optimization [2]. |

| Support Vector Regression (SVR) [2] | Effective in high-dimensional spaces, versatile via kernel functions, explainable. | Scenarios with clear margins of separation, smaller datasets. | Used for optimizing protocol configurations in asymmetric quantum networks [2]. |

| LightGBM [4] | Gradient boosting framework, fast training speed, high efficiency, handles large-scale data. | Large-scale tabular data, layer-wise model merging optimization. | Achieved R² > 0.92 and Kendall’s Tau > 0.79 in predicting merged model performance [4]. |

| Deep Learning (U-Net) [3] | High-fidelity for complex spatial patterns, benefits from transfer learning. | Subsurface flow simulations, image-like output prediction. | 75% reduction in computational cost for reservoir simulation using multi-fidelity learning [3]. |

| Gaussian Processes [2] | Provides uncertainty estimates, well-suited for continuous spaces. | Low-dimensional problems (<20 variables), experimental calibration. | Can be outperformed by SVR/RF in high-dimensional scenarios [2]. |

Experimental Protocol: Developing a Surrogate Model for Chromatographic Optimization

This protocol outlines the methodology for constructing and validating a surrogate model to optimize a Supercritical Fluid Extraction-Supercritical Fluid Chromatography (SFE-SFC) method, a relevant application in analytical chemistry and drug development [1].

Research Reagent and Computational Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Materials and Computational Tools for Surrogate Model Development

| Item / Tool Name | Function / Purpose |

|---|---|

| Chromatographic System (e.g., SFE-SFC Instrument) | Generates the high-fidelity experimental data required to train and validate the surrogate model. |

| Dataset of Historical Method Parameters & Outcomes | Serves as the foundational data for initial model training, containing inputs (e.g., pressure, temperature) and outputs (e.g., resolution, peak capacity). |

| Python Programming Environment | Core platform for model development, offering libraries for data manipulation, machine learning, and optimization algorithms. |

| LightGBM / Scikit-learn | Provides implementations of machine learning algorithms like Random Forest, SVR, and gradient boosting for building the surrogate model [2] [4]. |

| Optuna | A hyperparameter optimization framework used to automatically tune the surrogate model's parameters for maximum predictive accuracy [4]. |

| NetSquid / SeQUeNCe (Quantum Simulators) | Examples of high-fidelity simulators used in other fields, analogous to complex instrument simulations, which the surrogate is designed to approximate [2]. |

Step-by-Step Workflow

Step 1: Define the Optimization Objective and Search Space

- Objective Formulation: Clearly define the objective function, ( U(f, \mathbf{x}) ), which could be a chromatographic performance metric like resolution, peak capacity, or a weighted combination of multiple criteria [2].

- Parameter Identification: Identify the configurable instrument parameters, ( \mathbf{s} ), such as pressure, temperature, modifier concentration, and gradient profile time. Define their feasible ranges (e.g., ( X{\text{conf}} = [P{\text{min}}, P{\text{max}}] \times [T{\text{min}}, T_{\text{max}}] )) [2].

Step 2: Generate the Initial Training Dataset

- Design of Experiments (DoE): Use space-filling designs like Latin Hypercube Sampling or random sampling to generate ( k0 ) initial input sets ( {\mathbf{s}1, \mathbf{s}2, \ldots, \mathbf{s}{k0}} ) from the defined search space ( X{\text{conf}} ) [2].

- High-Fidelity Data Acquisition: For each input configuration ( \mathbf{s}i ), run the instrument or a high-fidelity simulation to collect the corresponding performance metrics. To account for stochasticity, perform ( n ) replicate runs (e.g., n=3) and use the mean performance, ( \bar{U}(f, \mathbf{s}i) ), as the output value [2].

Step 3: Construct and Train the Surrogate Model

- Model Selection: Choose an appropriate model from Table 1 (e.g., Random Forest or LightGBM) based on the problem dimensionality and data size [2] [4].

- Training and Validation: Split the initial dataset into training and test sets (e.g., 9:1 ratio). Train the selected model on the training set and validate its performance on the test set using metrics like R² (coefficient of determination) and Kendall’s Tau to ensure it accurately captures the input-output relationships [4].

Step 4: Iterative Model-Guided Optimization

- Acquisition and Evaluation:

- Use the trained surrogate to predict the performance of a large number of candidate parameter sets.

- Select the most promising candidates (e.g., those predicted to maximize the objective function) for empirical testing.

- Run the instrument or high-fidelity simulation for these selected points to obtain their true performance values.

- Augment the training dataset with these new, high-value data points.

- Model Refitting: Retrain the surrogate model on the expanded dataset to improve its accuracy, particularly in promising regions of the parameter space.

- Convergence Check: Repeat this cycle until the performance gains between iterations fall below a pre-defined threshold or the computational budget is exhausted.

Step 5: Final Validation and Deployment

- Blind Test Validation: Validate the final, optimized method parameters obtained from the surrogate on a set of blind test samples not used during the optimization process.

- Deployment: Implement the optimized method on the analytical instrument for routine analysis.

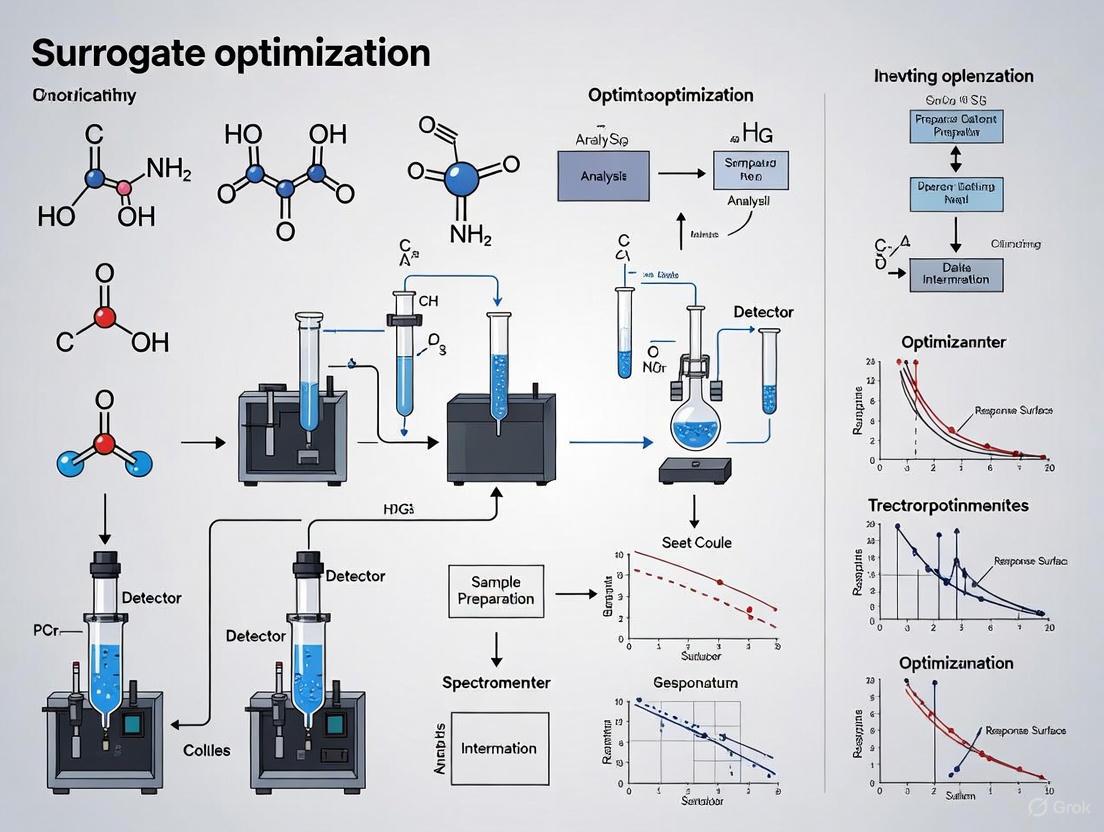

Surrogate Model Optimization Workflow

Diagram 1: Surrogate optimization workflow for analytical methods.

Advanced Application: Predictive Chemistry with Descriptor Prediction

Surrogate models are revolutionizing predictive chemistry, especially in data-scarce scenarios like reaction rate or selectivity prediction [5]. A key challenge is the computational cost of generating quantum mechanical (QM) descriptors, which are physically meaningful features used to build robust models.

Protocol: Comparing Descriptor vs. Hidden Representation Strategies

This protocol compares two advanced strategies for employing surrogates in predictive chemistry tasks.

Step 1: Surrogate Model Training for Descriptor Prediction

- Train a deep learning model to predict expensive-to-compute QM descriptors directly from the molecular structure. This model acts as the surrogate, enabling fast descriptor generation.

Step 2: Downstream Model Development via Two Pathways

- Path A: Using Predicted Descriptors

- Use the trained surrogate from Step 1 to generate QM descriptors for a large set of molecules.

- Feed these predicted descriptors as input features into a separate downstream machine learning model (e.g., a Random Forest) tasked with the final chemical property prediction.

- Path B: Using Hidden Representations

- Instead of using the surrogate's output (descriptors), extract the internal activations from one of its final layers—the hidden representations.

- Use these hidden representations as the input features for the downstream predictive model.

Step 3: Performance Evaluation and Strategy Selection

- Evaluate and compare the performance of the models from Path A and Path B on a held-out test set.

- Finding: Hidden representations often outperform predicted QM descriptors, as they capture rich, transferable chemical information not confined to pre-defined physical interpretations. Predicted descriptors may only be superior for very small datasets or when the descriptors are meticulously selected for the specific task [5].

Surrogate Strategies in Predictive Chemistry

Diagram 2: Two surrogate strategies for predictive chemistry.

In the fields of analytical chemistry and drug development, traditional experimentation often relies on iterative, trial-and-error approaches. These methods are notoriously resource-intensive, requiring significant time, costly materials, and expert personnel. Surrogate optimization presents a paradigm shift, using machine learning models to approximate complex, expensive-to-evaluate experimental processes. This data-driven strategy enables researchers to navigate parameter spaces intelligently, drastically reducing the number of physical experiments needed to reach optimal outcomes [1] [6]. These approaches are becoming indispensable for optimizing analytical instrumentation and methods, making research both faster and more cost-effective [6] [7].

Key Concepts and Optimization Frameworks

Surrogate optimization replaces a complex, "black-box" experimental process with a computationally efficient statistical model. This model is trained on initial experimental data and is used to predict the outcomes of untested parameter sets. An acquisition function then guides the selection of the most promising experiments to run next, balancing the exploration of uncertain regions with the exploitation of known high-performance areas [8].

Table 1: Comparison of Common Surrogate Modeling Approaches

| Model Type | Key Principle | Advantages | Best-Suited For |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gaussian Process (GP) [8] | A flexible, non-parametric Bayesian model. | Provides inherent uncertainty estimates; mathematically explicit. | Problems with smooth, continuous response surfaces; lower-dimensional spaces. |

| Bayesian Multivariate Adaptive Regression Splines (BMARS) [8] | Uses product spline basis functions for a nonparametric fit. | Handles non-smooth patterns and higher-dimensional spaces effectively. | Complex objective functions with potential sudden transitions or interactions. |

| Bayesian Additive Regression Trees (BART) [8] | An ensemble method based on a sum of small regression trees. | Excellent for capturing complex, non-linear interactions; built-in feature selection. | High-dimensional problems where a small subset of parameters is dominant. |

| Radial Basis Function Neural Networks (RBFNN) [9] | A neural network using radial basis functions as activation. | Fast training; excels at modeling complex, non-linear local variations. | Modeling intricate systems with high accuracy from experimental data. |

Two powerful frameworks for implementing these models are:

- Bayesian Optimization (BO): An indispensable tool for optimizing objective functions that are expensive to evaluate. BO uses a flexible surrogate model, like BMARS or BART, to approximate the underlying function and undergoes Bayesian updates as new data is acquired [8].

- Adaptive Design Optimization (ADO): A methodology that dynamically alters the experimental design in response to observed data. ADO chooses each subsequent stimulus or experimental condition to be maximally informative about the question of interest, ensuring no wasted trials [10].

Application Notes & Experimental Protocols

Case Study 1: Optimizing Liquid Chromatography Mass Spectrometry (LCMS) Parameters

Objective: To optimize the parameter settings of a Shimadzu Liquid Chromatography Mass Spectrometry (LCMS) 2020 instrument for the efficient flow injection analysis of Acetaminophen [6].

Experimental Workflow:

Protocol 1: QMARS-MIQCP-SUROPT for LCMS Optimization

Parameter Selection and Initial Design:

- Identify critical LCMS parameters for optimization (e.g., mobile phase composition, flow rate, interface voltage, desolvation line temperature).

- Define plausible min/max ranges for each parameter based on instrument specifications and chemical feasibility.

- Use a space-filling design (e.g., full factorial or Latin Hypercube) to select 15-20 initial data points across the parameter space [6].

Data Generation:

- Prepare standard solutions of Acetaminophen.

- For each parameter set from Step 1, perform flow injection analysis on the LCMS-2020 system.

- Record key performance metrics, including signal intensity (peak area), signal-to-noise ratio, and peak width [6].

Model Building and Iteration:

- Train a Quintic Multivariate Adaptive Regression Splines (QMARS) metamodel. This model will learn the relationship between your input parameters and the measured responses [6].

- Embed the QMARS model into a Mixed Integer Quadratically Constrained Program (MIQCP) for global optimization.

- Use the QMARS-MIQCP-SUROPT algorithm to propose the next set of LCMS parameters expected to yield the best performance (e.g., maximum signal intensity). The algorithm uses a modified "Sorted EEPA" approach to balance exploration and exploitation [6].

- Conduct the proposed experiment, record the results, and update the surrogate model with the new data point.

Validation:

- Repeat Step 3 for a pre-defined number of iterations or until performance convergence.

- Validate the final, model-proposed optimal parameters with three independent replicate runs.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for LCMS Optimization

| Item | Function / Rationale |

|---|---|

| Acetaminophen Analytical Standard | High-purity model analyte for system performance evaluation. |

| HPLC-Grade Water & Methanol | High-purity mobile phase components to minimize background noise and ion suppression. |

| Ammonium Acetate or Formic Acid | Common mobile phase additives to control pH and influence analyte ionization in the MS source. |

Case Study 2: Quantification of Drug Transporter Proteins using LC-MS/MS Proteomics

Objective: To develop a validated LC-MS/MS multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) method for the absolute quantification of P-glycoprotein (P-gp) in membrane protein isolates from tissues or cell lines [11].

Experimental Workflow:

Protocol 2: MRM Proteomics for Transporter Quantification

Surrogate Peptide Selection:

- Obtain the full protein sequence for the target transporter (e.g., Human P-gp, Uniprot ID P08183) from a database like UniprotKB [11].

- Perform in silico tryptic digestion using software tools.

- Apply filters to select the best surrogate peptide: uniqueness to the target protein (to avoid homologs), length (typically 7-20 amino acids), absence of chemically unstable residues (e.g., M, C), and favorable MS properties [11].

Peptide Synthesis and Qualification:

- Synthesize the purified unlabeled and stable isotope-labeled (SIS) versions of the selected peptide.

- Qualify the peptide by infusing it into the MS to optimize fragmentation and select the most intense precursor ion > product ion transitions for MRM [11].

Sample Preparation:

- Isolate membrane proteins from the biological matrix (tissue or cells) using ultracentrifugation.

- Determine total protein concentration.

- Digest the protein sample (e.g., 100 µg) with trypsin. This includes steps for denaturation, reduction of disulfide bonds, alkylation, and overnight enzymatic digestion [11].

- Add a known amount of the SIS peptide post-digestion as an internal standard to correct for sample preparation and ionization variability.

LC-MS/MS Analysis and Method Validation:

- Chromatography: Optimize LC parameters (column, gradient, flow rate) to achieve sharp, symmetrical peak elution for the peptide.

- Mass Spectrometry: Optimize MS parameters (collision energy, declustering potential) for the specific MRM transitions.

- Validation: Establish a calibration curve using the synthetic unlabeled peptide. Assess method for linearity, sensitivity (LLOQ), precision (CV < 15-20%), and accuracy [11].

Table 3: Key Materials for Targeted Proteomics

| Item | Function / Rationale |

|---|---|

| Stable Isotope-Labeled (SIS) Peptide | Internal standard for absolute quantification; corrects for sample loss and ion suppression. |

| Trypsin, Proteomic Grade | High-purity enzyme for specific and reproducible protein digestion. |

| Iodoacetamide | Alkylating agent to prevent reformation of disulfide bonds after reduction. |

| RIPA Lysis Buffer | For efficient extraction of membrane-bound transporter proteins. |

The adoption of surrogate model-based optimization represents a critical advancement for analytical chemistry and drug development. By moving beyond costly and time-consuming trial-and-error, these data-efficient strategies allow researchers to extract maximum information from every experiment. The detailed application notes and protocols provided for instrument parameter optimization and targeted proteomics serve as a practical roadmap for scientists to implement these powerful approaches, accelerating the pace of discovery and innovation.

In analytical chemistry, the development and optimization of instrumentation methods are fundamentally centered on understanding and controlling the relationship between a set of adjustable input parameters and the resulting output performance. Machine Learning (ML) has emerged as a transformative tool for modeling these complex, non-linear relationships, often where a precise theoretical model is intractable. At its core, an ML model acts as a universal function approximator, learning to map input features (e.g., chromatographic conditions) to output targets (e.g., peak resolution, sensitivity) from historical experimental data [12] [13]. This capability is particularly powerful in surrogate modelling, where an ML model serves as a computationally efficient stand-in for expensive or time-consuming laboratory experiments and complex simulations, thereby accelerating the optimization cycle for analytical methods such as Supercritical Fluid Chromatography (SFC) and Solid Phase Extraction (SPE) [1]. This document outlines the core principles and provides detailed protocols for leveraging ML to understand and exploit the mapping from input parameters to output performance within the context of analytical chemistry research.

Core Principles of Input and Output Parameters

The foundation of any ML application is a clear definition of its inputs and outputs. Their correct identification and structuring are prerequisites for a successful model.

Input Parameters (Features)

Input parameters, also known as features or predictors, are the variables or attributes provided to the ML model [12]. In analytical chemistry, these typically represent the controllable or measurable conditions of an instrument or a process. The nature of these features dictates the appropriate preprocessing steps.

Table 1: Typology of Input Parameters in Analytical Chemistry

| Feature Type | Description | Examples in Analytical Chemistry | Common Preprocessing |

|---|---|---|---|

| Numerical [12] | Continuous or discrete numerical values. | Temperature, Pressure, Flow Rate, Gradient Time, pH, Injection Volume. | Scaling, Standardization, Logarithmic Transformation [14]. |

| Categorical [12] | Discrete categories or labels. | Type of Stationary Phase, Solvent Supplier, Detector Type. | One-Hot Encoding, Label Encoding. |

| Textual [12] | Text data. | Chemical nomenclature, notes from a lab journal. | Tokenization, TF-IDF, Word Embeddings. |

Output Parameters (Targets)

Output parameters, or targets, are the values the model aims to predict [12]. These represent the key performance indicators of the analytical method.

Table 2: Types of Output Parameters and ML Tasks

| Task Type | Output Parameter Nature | Examples in Analytical Chemistry |

|---|---|---|

| Regression [12] | Predicting continuous numerical values. | Peak Area, Retention Time, Resolution, Sensitivity, Recovery Yield. |

| Classification [12] | Assigning input data to discrete categories. | Method Success (Pass/Fail), Peak Shape Quality (Good/Acceptable/Poor), Compound Identity. |

| Clustering [12] | Identifying groups in data without predefined labels. | Discovering distinct patterns in failed method runs. |

Data Structure and Granularity

For analysis, data must be structured in a tabular format where each row represents a unique record or observation—for instance, a single experimental run [15]. Each column represents a specific feature or target variable [15]. The granularity, or what a single row represents, must be clearly defined and consistent, as it impacts everything from visualization to the validity of the model [15]. A unique identifier for each row is considered a best practice.

Surrogate Modeling for Analytical Instrument Optimization

Surrogate modelling is an advanced application of ML that is particularly suited for optimizing analytical instrumentation and processes.

Definition and Role

A surrogate model is a data-driven, approximate model of a more complex process. In chromatography, the "complex process" could be a resource-intensive high-fidelity simulation of mass transfer in a column or the actual physical experimentation, which is expensive and time-consuming [1]. The ML model is trained on a limited set of input-output data from this complex process and learns to approximate its behavior, serving as a fast, "surrogate" for the original [1].

Benefits in Chromatographic Method Development

- Enhanced Experimental Efficiency: Surrogate models guide optimization strategies, allowing researchers to explore a vast parameter space computationally before committing to wet-lab experiments [1].

- Predictive Capabilities: They enable predictive analysis, forecasting system performance under untested conditions, and support real-time control and predictive maintenance in industrial settings [1].

- Outperformance of Traditional Methods: Surrogate-assisted optimization can outperform traditional response surface methodologies by handling higher dimensions and more complex, non-linear relationships effectively [1].

Experimental Protocols for Mapping Inputs to Outputs

A rigorous, systematic approach to experimentation is required to build robust ML models. The following protocol outlines the key stages.

Protocol: ML-Driven Method Optimization Workflow

Objective: To systematically optimize an analytical method (e.g., SFC separation) by building and validating an ML surrogate model that maps instrument parameters to performance metrics.

Materials and Reagents:

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions & Essential Materials

| Item / Solution | Function / Role in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Analytical Standard Mixture | The target analytes for separation; used to generate the performance data (outputs). |

| Chromatographic System (e.g., SFC/SFE) | The instrument platform to be optimized; generates the raw data. |

| Mobile Phase Components (e.g., CO₂, Co-solvents) | Key input parameters whose composition and flow rate are critical variables. |

| Stationary Phase Columns | The separation media; the type of column is often a categorical input parameter. |

| Data Tracking Spreadsheet / Electronic Lab Notebook (ELN) | To systematically record all input parameters and output performance for every experimental run [14]. |

| ML Experiment Tracking Tool (e.g., Weights & Biases, MLflow) | To log model parameters, code versions, and results for reproducibility [14]. |

Procedure:

Hypothesis and Baseline Definition:

- Clearly define the optimization goal (e.g., maximize resolution between two peaks in under 5 minutes).

- Establish a baseline using a standard or initial method to understand the starting performance [14].

Design of Experiments (DoE) and Data Collection:

- Select key input parameters (e.g., co-solvent percentage, pressure, temperature) and their realistic ranges.

- Use a DoE approach (e.g., Full Factorial, Central Composite) to generate a set of experimental conditions that efficiently covers the parameter space.

- Execute the experiments as per the DoE matrix, meticulously recording all input parameters for each run.

- For each run, measure the output performance metrics (e.g., retention time, resolution, peak capacity).

Data Preprocessing and Feature Engineering:

- Structure the data into a single table, where each row is one experimental run and columns are inputs and outputs [15].

- Clean the data: handle missing values, and identify potential outliers by examining distributions [15].

- Perform feature engineering: scale numerical features, encode categorical variables, and consider creating new features by transforming existing ones (e.g., creating a "elution strength" parameter from mobile phase composition) [14].

Model Training and Hyperparameter Tuning:

- Split the dataset into training and testing sets (e.g., 80/20 split).

- Select candidate models (e.g., Random Forest, Gradient Boosting, Neural Networks) [14].

- Implement hyperparameter tuning using methods like Grid Search or Bayesian Optimization to find the optimal model configuration [14].

- Train the final model on the full training set with the optimized hyperparameters.

Model Validation and Interpretation:

- Validate the model on the held-out test set. Use metrics relevant to the task: Mean Squared Error (MSE) for regression, accuracy for classification.

- Use interpretability techniques (e.g., SHAP plots, feature importance scores) to understand which input parameters most influence the output performance [12] [13]. This is crucial for explaining the model and gaining scientific insight.

Prediction and Verification:

- Use the trained surrogate model to predict performance across the entire input parameter space and propose an optimal set of conditions.

- Perform a final wet-lab experiment using these model-proposed conditions to verify the prediction and confirm the optimization.

Implementation: From Data to Decision

The final stage involves translating the model's insights into actionable knowledge.

Visualizing the Learned Relationship

Understanding the functional mapping learned by an ML model is key to its utility. While complex models are often seen as "black boxes," techniques exist to extract and visualize input-output relationships.

For example, after training a model, one can create partial dependence plots which show how the predicted output changes as a specific input feature is varied while averaging out the effects of all others. This visualization effectively displays the functional relationship between an individual input and the output, as learned by the model. While deriving an exact, human-readable equation (like (3x³+0.5y²...)) from a complex model is generally not feasible, these visualization techniques provide a powerful and interpretable approximation of the mapping [13].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Considerations

Table 4: Essential Practices for Robust ML Modeling

| Practice | Description | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Establish a Baseline [14] | Define the performance of a standard or initial method before optimization. | Provides a reference point to quickly identify if ML-driven changes are genuine improvements. |

| Maintain Consistency [14] | Use version control for code and data, and ensure consistent experimental conditions. | Reduces human error and ensures results are reproducible by your team and others. |

| Implement Automation [14] | Automate data ingestion, pre-processing, and model training where possible (MLOps). | Improves speed, efficiency, and reduces manual errors in the experimentation pipeline. |

| Track Metadata Meticulously [14] | Record model parameters, data features, metrics, and environment details for every experiment. | Enables full traceability and allows for the analysis of what factors drive model performance. |

Surrogate optimization is transforming the landscape of analytical chemistry instrumentation by introducing data-driven methodologies that enhance predictive accuracy, conserve valuable resources, and dramatically accelerate development cycles. As the field grapples with increasingly complex samples and economic pressures, these simplified, AI-powered models of complex systems are becoming indispensable. They enable researchers to navigate vast experimental spaces intelligently, replacing costly trial-and-error approaches with guided, predictive optimization [1] [16]. This shift is particularly crucial in chromatography, where method development has traditionally been laborious and resource-intensive. The integration of machine learning-based surrogate models is now guiding optimization strategies and supporting predictive analysis, opening doors for real-time control and data-driven decision-making in industrial settings [1]. This document outlines specific application notes and experimental protocols to help researchers harness these advantages in analytical chemistry and drug development.

Application Notes

Predictive Capabilities in Chromatographic Method Development

Application Note AN-101: Surrogate-Assisted Optimization of SFC Methods

- Objective: To efficiently optimize Supercritical Fluid Chromatography (SFC) separation methods using surrogate models, improving predictive accuracy over traditional response surface methodologies.

- Background: In chromatographic method development, the relationship between instrumental parameters (e.g., temperature, pressure, modifier composition) and chromatographic outcomes (e.g., resolution, peak capacity) is complex and often non-linear. Surrogate models serve as computationally inexpensive approximators of this relationship, allowing for rapid prediction of outcomes under untested conditions [1].

- Key Findings:

- A study presented at HPLC 2025 demonstrated that surrogate modelling can guide optimization strategies and support predictive capabilities in chromatographic systems more efficiently than traditional methods [1].

- Machine learning-based surrogate models can outperform traditional response surface modeling, enabling predictive maintenance and real-time control in industrial chromatographic systems [1].

- The PRESTO (Predictive REcommendation of Surrogate models to approximate and Optimize) framework provides a systematic, automated procedure for selecting the most appropriate surrogate modeling technique (e.g., Gaussian Process Regression, Artificial Neural Networks) for a given dataset and application, be it surface approximation or optimization [17].

Table 1: Quantitative Impact of Predictive Surrogate Modeling in Chemistry

| Metric | Traditional RSM | Surrogate-Assisted Optimization | Data Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental Efficiency | Baseline | More efficient experimentation [1] | HPLC 2025 Interview |

| Optimization Performance | Sub-optimal solutions | Finds better solutions [18] | Chemical Engineering Science |

| Model Selection | Relies on user expertise | Automated, systematic via PRESTO [17] | Chemical Engineering Science |

Resource Conservation in Analytical Chemistry

Application Note AN-102: Minimizing Experimental Consumption via Hybrid Modeling

- Objective: To significantly reduce the consumption of expensive solvents, reagents, and instrument time during analytical method development and process optimization.

- Background: Resource-intensive experimentation presents a major bottleneck in chemical research and development. Surrogate models address this by constructing approximations from limited data, minimizing the need for exhaustive physical experiments or computationally expensive simulations [17] [19].

- Key Findings:

- Hybrid analytical surrogate models, which combine data-driven surrogate models with mechanistic equations, are particularly appealing as they are easier to handle and optimize than full-scale simulations [18].

- Global optimization of these hybrid models has been shown to outperform that of pure black-box models, leading to more efficient resource utilization [18].

- The overarching principle of surrogate-based optimization is to replace an expensive "black-box" function evaluation (e.g., a long simulation or a physical experiment) with a cheaper-to-evaluate model, thus conserving computational and material resources [19].

Table 2: Resource Conservation Benefits of Surrogate Optimization

| Resource Type | Conservation Mechanism | Quantitative Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Solvents & Reagents | Reduces experimental runs via predictive modeling | Supports green chemistry initiatives by minimizing waste [16] |

| Instrument Time | Optimizes methods in-silico before physical testing | Increases laboratory throughput and operational efficiency |

| Computational Resources | Uses cheaper surrogate models in place of high-fidelity simulations | Makes complex process optimization feasible where it was previously prohibitive [17] |

Accelerated Development Cycles

Application Note AN-103: Rapid Alloy Design Using Bayesian Multi-Objective Optimization

- Objective: To accelerate the development of multicomponent alloys with targeted properties by applying Bayesian multi-objective optimization.

- Background: The design of new materials, such as multicomponent alloys, requires balancing multiple, often competing, property objectives. Traditional experimentation is slow and costly. Bayesian optimization protocols based on active learning principles can efficiently navigate complex design spaces with limited evaluation budgets [20].

- Key Findings:

- The qEHVI (parallel Expected Hypervolume Improvement) acquisition function has demonstrated impressive performance in finding the optimum Pareto front for 1-, 2-, and 3-objective Aluminum alloy optimization problems within a limited evaluation budget [20].

- This approach is a prerequisite for guiding autonomous and high-throughput materials design and discovery processes, dramatically shortening development timelines [20].

- In the broader analytical instrumentation market, the drive for accelerated development is reflected in strong sector growth, with major suppliers reporting increased revenues driven by demand from pharmaceutical and chemical research [21].

Table 3: Market Drivers for Accelerated Development in Analytical Chemistry

| Driver | 2025 Market Context | Impact on Development Speed |

|---|---|---|

| Pharmaceutical R&D | Pharmaceutical analytical testing market valued at \$9.74B [16] | Drives investment in high-throughput tools like LC, GC, and MS [21] |

| AI Integration | AI algorithms used to optimize chromatographic conditions [16] | Reduces time for method development and data analysis |

| Instrument Demand | Liquid chromatography and mass spectrometry sales up high single digits [21] | Indicates a need for faster, more reliable analytical workflows |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol P-101: Surrogate Model Selection using the PRESTO Framework

Objective: To automatically select an optimal surrogate modeling technique for a given dataset without the computational expense of training multiple models.

Materials and Reagents:

- Computing Environment: Python/R or equivalent statistical software.

- Input Data: A dataset comprising input variables (e.g., chromatographic parameters) and corresponding output responses (e.g., retention time, resolution).

- PRESTO Tool: A random forest-based classification tool trained to recommend from candidate models like ALAMO, ANN, GPR, MARS, etc. [17].

Procedure:

- Data Preparation: Compile and clean your experimental or simulation dataset. Ensure it is structured in a matrix format (inputs vs. outputs).

- Attribute Extraction: Calculate dataset characteristics (attributes) that will serve as inputs for PRESTO. These may include measures of linearity, smoothness, and distribution characteristics, among others [17].

- Model Classification: For each candidate surrogate modeling technique in PRESTO's library, the tool will classify it as "recommended" or "not recommended" based on the calculated attributes of your dataset.

- Model Construction & Validation: Construct the surrogate models flagged as "recommended" by PRESTO. Validate the model's predictive performance using a hold-out test set or cross-validation.

Protocol P-102: Bayesian Multi-Objective Optimization for Material Properties

Objective: To identify a set of optimal material compositions (Pareto front) that balance multiple target properties using Bayesian optimization.

Materials and Reagents:

- High-Throughput Experimentation Setup: Or a precise simulation tool for evaluating material properties.

- Software: Bayesian optimization library (e.g., BoTorch, Ax) that implements acquisition functions like qEHVI and qNEHVI [20].

Procedure:

- Define Objective Functions: Identify the key material properties (e.g., strength, conductivity, cost) to be optimized. Formulate the problem as a minimization or maximization of these objectives.

- Set Design Constraints: Define the bounds of the design space (e.g., permissible composition ranges for each alloy element).

- Initial Sampling: Perform an initial set of experiments or simulations (e.g., via Latin Hypercube Sampling) to get baseline data.

- Iterative Optimization Loop: a. Surrogate Model Training: Fit separate surrogate models (e.g., Gaussian Processes) to each objective function based on all data collected so far. b. Acquisition Function Optimization: Use the qEHVI acquisition function to identify the next most promising sample(s) that maximize the expected hypervolume improvement [20]. c. Evaluation: Run the experiment or simulation at the proposed sample point(s) to obtain the true objective values. d. Update Dataset: Append the new data to the existing dataset.

- Termination: Repeat Step 4 until the evaluation budget is exhausted or the Pareto front is sufficiently converged.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Key Reagents, Materials, and Software for Surrogate Optimization

| Item Name | Function/Application in Surrogate Optimization |

|---|---|

| ALAMO (Automated Learning of Algebraic Models using Optimization) | A surrogate modeling technique used to develop simple, accurate algebraic models from data [17]. |

| Gaussian Process Regression (GPR) | A powerful surrogate modeling technique that provides not just predictions but also uncertainty estimates, which is crucial for Bayesian optimization [17] [19]. |

| Bayesian Optimization Software (e.g., BoTorch) | Libraries that implement acquisition functions like qEHVI for efficient multi-objective optimization of expensive black-box functions [20]. |

| Liquid Chromatography (LC) Consumables | Columns and solvents used in the physical experiments that generate data for building chromatographic surrogate models [21]. |

| Process Simulation Software (e.g., gPROMS) | High-fidelity simulators used to generate data for building surrogate models of chemical processes, as demonstrated in the cumene production case study [17]. |

| PRESTO Framework | A random forest-based tool that recommends the best surrogate modeling technique for a given dataset, avoiding trial-and-error [17]. |

Implementing Surrogate Models: Techniques and Real-World Applications in Biomedicine

Within modern analytical chemistry, particularly in pharmaceutical development, the demand for robust and high-resolution separation techniques is paramount. Two-dimensional liquid chromatography (2D-LC) has emerged as a powerful solution for analyzing complex mixtures, such as pharmaceutical formulations and their metabolites, which are often challenging to resolve with one-dimensional chromatography [22] [23]. However, the method development process for 2D-LC is notoriously complex and time-consuming, often involving the optimization of numerous interdependent parameters and requiring significant expertise [23].

This application note frames the use of ChromSim software within a broader thesis on surrogate optimization for analytical instrumentation. We detail a case study demonstrating how ChromSim, a Python library for microscopic simulation, can be employed as a computational surrogate model to streamline and accelerate the 2D-LC method development process. By creating a digital twin of the chromatographic system, ChromSim allows researchers to perform in-silico experiments, drastically reducing the number of physical experiments needed. This approach aligns with emerging trends in analytical chemistry that leverage data science tools and machine learning to enhance predictive capabilities and operational efficiency in the lab [1] [23] [16].

ChromSim is an open-source Python library specifically designed for microscopic crowd motion simulation [24]. Its application to chromatography optimization represents an innovative cross-disciplinary use case. The software implements numerical methods described in the academic text "Crowds in equations: an introduction to the microscopic modeling of crowds" [24].

In the context of 2D-LC, ChromSim serves as a surrogate model, a computational proxy for the physical chromatographic system. Surrogate models are simplified, data-driven representations of complex systems or processes that can predict outcomes based on input parameters, thereby reducing the need for costly and time-consuming experimental runs [25] [1]. The core functionality of ChromSim allows researchers to model the movement and separation of analyte "particles" through a simulated chromatographic environment, predicting retention behaviors and separation outcomes under various conditions.

The key advantage of using a surrogate modeling approach like ChromSim lies in its ability to perform virtual screening of method parameters. This includes testing different combinations of stationary phases, gradient profiles, and modulation strategies before any laboratory work begins. This predictive capability is particularly valuable in 2D-LC, where the experimental optimization of a single method can span several months using traditional approaches [23].

Surrogate Optimization Methodology

Theoretical Foundation of Surrogate Modeling

Surrogate modeling, in the context of analytical chemistry, involves creating a predictive computational model that approximates the behavior of a physical experiment. This approach is particularly valuable when experimental runs are expensive, time-consuming, or complex [25] [1]. An effective surrogate model must balance computational efficiency with predictive accuracy.

The application of surrogate modeling to chromatographic optimization addresses a fundamental challenge in modern laboratories: the need to develop robust methods while minimizing resource consumption. As noted in recent analytical chemistry trends, data-driven approaches are transforming method development by enabling scientists to navigate complex parameter spaces more efficiently [23] [16]. Surrogate models like ChromSim function as adaptive sampling tools, guiding the selection of the most informative experimental conditions to test physically, thereby maximizing knowledge gain per experiment [25].

Adaptive Sampling for Model Training

The accuracy of a surrogate model depends heavily on the quality and distribution of the training data. In this methodology, we employ an adaptive sampling technique based on distance density and local complexity [25]. This approach quantitatively assesses two critical factors:

- Distance Density: Measures the sparsity of existing sampling points in the parameter space, ensuring new experimental points are distributed in underrepresented regions.

- Local Complexity: Quantifies the change complexity of response values (e.g., retention times, peak shapes) near potential new sample points, giving priority to areas where the system behavior is more variable or difficult to predict.

This dual-metric approach ensures that the surrogate model is refined with high-quality sample points distributed in key areas of the experimental space, enabling the establishment of a high-precision predictive model with fewer physical experiments [25].

Integration with 2D-LC Parameters

For 2D-LC optimization, the surrogate model must account for parameters from both chromatographic dimensions. The table below outlines the key parameters managed through the ChromSim surrogate model.

Table 1: Key 2D-LC Parameters for Surrogate Model Optimization

| Parameter Category | Specific Parameters | Optimization Goal |

|---|---|---|

| First Dimension | Stationary phase chemistry, Column length and diameter, Flow rate, Gradient profile (time, %B), Temperature | Maximize resolution of primary components of interest |

| Second Dimension | Stationary phase chemistry (orthogonal to 1D), Column dimensions, Flow rate, Gradient or isocratic conditions, Cycle time | Achieve fast separations within the modulation cycle |

| System Parameters | Modulation time, Injection volume, Detection wavelength | Minimize band broadening, maintain resolution |

Experimental Protocol

Instrumentation and Reagents

This protocol is designed for a comprehensive 2D-LC system comprising two binary pumps, an autosampler with temperature control, a column oven, a diode array detector (DAD), and a heart-cutting interface with a two-position, six-port switching valve equipped with sampling loops.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

| Item | Function/Description | Example Vendor/Part |

|---|---|---|

| Analytical Standards | Favipiravir and metabolite surrogates for method development | Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) |

| First Dimension Column | C18 stationary phase (e.g., 150 mm x 4.6 mm, 2.7 µm) | Various manufacturers (e.g., Waters, Agilent) |

| Second Dimension Column | Orthogonal chemistry (e.g., Phenyl-Hexyl, 50 mm x 3.0 mm, 1.8 µm) | Various manufacturers (e.g., Waters, Agilent) |

| Mobile Phase A (1D & 2D) | Aqueous buffer (e.g., 10 mM ammonium formate, pH 3.5) | Prepared in-house with HPLC-grade water |

| Mobile Phase B (1D & 2D) | Organic modifier (e.g., acetonitrile or methanol) | HPLC-grade |

| Heart-Cutting Valve | Automated switching valve with dual loops | (e.g., Cheminert C72x series) |

| Data Acquisition Software | Controls instrument, data collection, and valve switching | (e.g., OpenLAB CDS, Empower) |

Software Configuration and Initialization

- Environment Setup: Install ChromSim Release 2.0 from the official repository (www.cromosim.fr) and required Python dependencies (NumPy, SciPy, Matplotlib) in a virtual environment.

- System Definition: Input the 2D-LC system parameters into ChromSim, including column dimensions for both dimensions, dead volumes, and potential gradient delay volume.

- Initial Parameter Space Definition: Define the realistic ranges for the key variable parameters to be optimized (see Table 1).

Step-by-Step Optimization Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the core iterative process of using the ChromSim surrogate model to guide physical experimentation.

- Initial Experimental Calibration: Execute a small, strategically designed set of physical 2D-LC experiments (e.g., 10-15 runs) covering the defined parameter space. These experiments should measure critical responses such as retention times, peak widths, and resolution for key analyte pairs.

- Model Training and Validation: Input the experimental data into ChromSim to train and calibrate the initial surrogate model. Validate the model's predictive accuracy by comparing its predictions for a separate, small validation set against actual experimental results.

- Iterative Optimization Cycle:

- Virtual Screening: Use the trained ChromSim model to run extensive in-silico experiments (thousands of virtual runs), predicting separation outcomes for different parameter combinations.

- Adaptive Sampling Analysis: Apply the distance density and local complexity criteria [25] to the model's predictions to identify the most informative experimental conditions that should be tested next.

- Targeted Physical Experiments: Perform only the select, high-value experiments identified by ChromSim in the laboratory.

- Model Refinement: Update the ChromSim surrogate model with the new experimental results to improve its accuracy for the next iteration.

- Final Method Validation: Once the model predicts a parameter set that meets all separation criteria (e.g., resolution > 1.5 for all critical pairs), physically execute this final method to validate its performance in the laboratory according to standard validation protocols.

Data Analysis

ChromSim provides quantitative outputs for predicted retention times and peak shapes. The key metric for optimization is the critical resolution (Rs) between all adjacent peaks of interest. The optimization goal is to maximize the minimum Rs across the chromatogram. The model's performance is evaluated by calculating the root mean square error (RMSE) between predicted and experimentally observed retention times from the validation set, ensuring it is within pre-defined acceptable limits (e.g., < 2% of the total run time).

Results and Discussion

Optimization Efficiency

The implementation of the ChromSim surrogate model led to a significant reduction in the resources required for 2D-LC method development. The traditional approach, which relies heavily on one-factor-at-a-time or full factorial design of experiments, typically required 3-4 months of intensive laboratory work for a complex separation [23]. In contrast, the surrogate-assisted approach achieved an optimized method for the simultaneous determination of favipiravir and its metabolite surrogates in approximately 6 weeks.

This 50% reduction in method development time was achieved by drastically cutting the number of physical experiments. Where a traditional response surface methodology might require 50-80 experimental runs, the adaptive sampling guided by ChromSim yielded an optimal method after only 25-30 physical runs. This translates to direct cost savings in terms of solvent consumption, instrument time, and analyst hours, while also aligning with the principles of green analytical chemistry by reducing waste [16].

Table 3: Comparison of Method Development Approaches

| Development Metric | Traditional Approach | ChromSim Surrogate Approach | Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Estimated Development Time | 3-4 months | 6 weeks | ~50% reduction |

| Typical Number of Physical Experiments | 50-80 | 25-30 | ~60% reduction |

| Reliance on Expert Knowledge | High | Medium (encoded in model) | Lower barrier to entry |

| Exploration of Parameter Space | Limited due to practical constraints | Extensive via in-silico testing | More comprehensive |

Analytical Performance of the Optimized 2D-LC Method

The final method parameters identified through ChromSim optimization demonstrated robust analytical performance. The heart-cutting 2D-LC method successfully achieved baseline resolution (Rs > 1.5) for all critical peak pairs of favipiravir and its metabolite surrogates, a result that was not attainable with single-dimensional LC [22]. The predicted retention times from the final ChromSim model showed excellent correlation with experimental values, with an RMSE of less than 0.15 minutes across the entire separation, confirming the high predictive fidelity of the properly trained surrogate.

The effectiveness of this approach underscores a broader shift in analytical chemistry toward data-driven methodologies [23] [16]. As presented at the HPLC 2025 conference, techniques like surrogate modeling are now enabling "faster, more flexible method development in complex analytical setups... by reducing experimental burden and enhancing predictive power" [23]. This case study confirms that ChromSim can function effectively as a surrogate model within this modern paradigm.

This application note has detailed a successful implementation of ChromSim software as a computational surrogate for optimizing a complex 2D-LC method. The case study demonstrates that this approach can cut method development time and resource consumption by approximately half compared to traditional approaches. By leveraging an adaptive sampling strategy, the ChromSim model efficiently guided experimentation toward the most informative points in the parameter space, resulting in a robust, high-resolution method for analyzing a pharmaceutical compound and its metabolites.

The findings strongly support the core thesis that surrogate optimization represents a powerful tool for advancing analytical instrumentation research. In an era where analytical workflows are becoming increasingly data-driven and resource-conscious [1] [16], the integration of simulation and modeling tools is no longer a luxury but a necessity for maintaining efficiency and innovation. The principles outlined here for 2D-LC are transferable to other complex analytical techniques, paving the way for more intelligent, predictive, and sustainable laboratory practices in pharmaceutical development and beyond.

The quantitative analysis of acetaminophen (APAP) in biological matrices is a cornerstone of pharmaceutical research, critical for pharmacokinetic studies and therapeutic drug monitoring. This application note details a systematic approach to optimizing a Flow Injection Analysis (FIA) method coupled with LC-MS/MS for the rapid and sensitive determination of acetaminophen. The content is framed within a broader research thesis exploring surrogate modelling for the optimization of analytical chemistry instrumentation, demonstrating how data-driven strategies can enhance method development efficiency and system performance [1].

Flow Injection Analysis provides a robust platform for high-throughput sample introduction, eliminating the need for chromatographic separation and significantly reducing analysis time. When integrated with the selectivity and sensitivity of LC-MS/MS, FIA becomes a powerful tool for rapid analyte quantification. This case study exemplifies the application of surrogate modelling to streamline the optimization of this combined system, moving beyond traditional one-variable-at-a-time approaches to a more efficient, multivariate paradigm [1].

Experimental Design and Surrogate Modelling Framework

Surrogate-Assisted Optimization Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the systematic, data-driven workflow employed for the FIA-LC-MS/MS optimization, which replaces resource-intensive traditional methods.

Key Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details the essential materials and reagents required to implement the optimized FIA-MS/MS method for acetaminophen analysis.

| Item | Function / Specification | Example / Source |

|---|---|---|

| Acetaminophen Standard | Primary reference standard for calibration and quality control. Purity: ≥ 99% [26]. | Sigma-Aldrich, Toronto Research Chemicals [27] |

| Stable Isotope Internal Standard | Corrects for matrix effects and instrumental variability. | Acetaminophen-d4 [27] |

| Mass Spectrometry Grade Solvents | Mobile phase and sample reconstitution; minimize background noise and ion suppression. | Methanol, Acetonitrile (e.g., from Merck [27]) |

| Aqueous Mobile Phase Additive | Promotes protonation in positive ESI mode, enhancing [M+H]+ ion signal. | 0.1% Formic Acid in water [28] [29] |

| Blank Human Matrix | Validates method specificity and assesses matrix effects for bioanalytical applications. | Blank human plasma or serum [28] [27] |

| Protein Precipitating Agent (PPA) | Rapid and efficient sample clean-up for plasma samples. | Acetonitrile or Methanol with 0.1% Formic Acid [28] [27] |

Methodology

Instrumental Configuration

The optimized method utilizes a streamlined FIA-MS/MS configuration.

- Flow Injection Analysis System: An HPLC system (e.g., Shimadzu UHPLC or Agilent 1260 Infinity II) is re-purposed for FIA by replacing the analytical column with a narrow-bore PEEKsil tubing connector to minimize carryover [30]. The system includes a binary pump, degasser, and thermostated autosampler.

- Mass Spectrometer: A triple quadrupole mass spectrometer (e.g., SCIEX QTRAP 5500 or AB Sciex Triple Quad 6500+) equipped with an Electrospray Ionization (ESI) source is used for detection [28] [27].

- Key MS Parameters:

Optimized FIA-MS/MS Protocol

This protocol is the result of the surrogate modelling optimization and is designed for the direct analysis of acetaminophen in protein-precipitated plasma samples.

Step 1: Sample Preparation (Protein Precipitation)

- Piper 50 µL of human plasma into a 1.75 mL microtube.

- Add 10 µL of internal standard working solution (e.g., Acetaminophen-d4).

- Add 940 µL of ice-cold acetonitrile containing 0.1% formic acid as the protein precipitating agent [29].

- Vortex the mixture vigorously for 5 minutes and then centrifuge at 13,200 rpm for 5 minutes at 4°C.

- Transfer 100 µL of the clear supernatant and dilute with 400 µL of the FIA mobile phase. Vortex for 2 minutes before injection [29].

Step 2: FIA-MS/MS Analysis

- Mobile Phase: Methanol and 0.1% formic acid in water (50:50, v/v) [28].

- Flow Rate: 0.5 mL/min [28].

- Injection Volume: 10 µL [28].

- Injection Cycle: The total run time is 2.0 minutes per sample, comprising:

- Sample Injection and Data Acquisition: 0.5 minutes

- System Wash with Strong Solvent: 1.0 minute

- Re-equilibration: 0.5 minutes

- Detection: MRM scan type with a dwell time of 100 ms per transition [27].

FIA-MS/MS Logical Process Flow

The sequence below details the instrumental and data acquisition logic executed for each sample.

Results and Discussion

Optimized Method Performance Characteristics

The performance of the surrogate-optimized FIA-MS/MS method was rigorously validated against standard bioanalytical guidelines [28]. Key quantitative performance data are summarized below.

| Validation Parameter | Result for Acetaminophen | Acceptance Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Linear Range | 100 - 20,000 ng/mL [28] | Correlation coefficient (R) ≥ 0.99 [28] |

| Lower Limit of Quantification (LLOQ) | 100 ng/mL [28] | Signal-to-noise ≥ 5; Accuracy & Precision ≤ ±20% [28] |

| Accuracy (% Deviation) | 94.40 - 99.56% (Intra-day) [29] | 85 - 115% (80 - 120% for LLOQ) [28] |

| Precision (% RSD) | 2.64 - 10.76% (Intra-day) [29] | ≤ 15% (≤ 20% for LLOQ) [28] |

| Carryover | < 0.15% [30] | Typically ≤ 0.2% |

| Analytical Throughput | ~30 samples/hour | N/A |

Impact of Surrogate Modelling on Method Development

The application of machine learning-based surrogate modelling fundamentally transformed the optimization from a sequential, labor-intensive process to a parallel, predictive one [1]. This approach allowed for the efficient exploration of complex interactions between critical FIA and MS parameters—such as flow rate, solvent composition, and source temperature—that are difficult to model with traditional response surface methodologies. By building a predictive model from a strategically designed set of initial experiments, the surrogate model identified the global optimum with significantly fewer experimental runs, saving time and valuable reagents [1]. This data-driven strategy is particularly advantageous for methods like FIA-MS/MS, where experimental runs, while faster than LC-MS/MS, still require careful resource management in high-throughput environments.

This case study successfully demonstrates the development and optimization of a rapid, sensitive, and robust FIA-MS/MS method for the quantification of acetaminophen. The method delivers a high analytical throughput of approximately 30 samples per hour with excellent sensitivity and precision, making it highly suitable for high-volume applications like therapeutic drug monitoring and pharmacokinetic screening [28].

Furthermore, framing this work within the context of surrogate modelling for analytical instrumentation highlights a powerful modern paradigm. The use of machine learning-driven surrogates significantly accelerates the method development lifecycle, reduces costs, and enhances the robustness of the final analytical procedure [1]. This approach can be extended to optimize methods for other analytes and on different instrumental platforms, representing a significant advancement in the field of analytical chemistry research and development.

The purification of monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) represents a critical bottleneck in biopharmaceutical manufacturing, accounting for 50-80% of total production costs [31] [32]. Capture chromatography, particularly Protein A affinity chromatography, serves as the cornerstone of downstream processing due to its exceptional selectivity and ability to achieve >95% purity in a single step [31] [32]. However, traditional process optimization faces significant computational challenges when using dynamic models based on systems of non-linear partial differential equations, which simulate critical operations like breakthrough curve behavior [33]. These simulations incur high computational costs, creating barriers to rapid process development.

Surrogate optimization has emerged as a transformative approach to address these limitations. By implementing surrogate functions to approximate the most computationally intensive calculations, researchers have demonstrated a 93% reduction in processing time while maintaining accurate results [33]. This approach combines commercial software with specialized optimization frameworks to perform sensitivity analyses and multi-objective optimization on mixed-integer process variables, making advanced process optimization accessible for industrial applications without sacrificing customizability or increasing system requirements [33].

Surrogate-Based Optimization Framework

Computational Framework Architecture

The surrogate optimization framework for capture chromatography replaces the most computationally demanding elements of traditional simulation with efficient approximation functions. In chromatography process simulation, the breakthrough curve simulation using finite element methods represents the primary computational bottleneck, yet provides only a single parameter value (yield) for objective function evaluation [33]. The surrogate framework addresses this inefficiency through a structured approach:

The core innovation involves creating a surrogate function that estimates process yield as a function of relative load (the quotient of load volume and membrane volume). This function is constructed by building a library of yield values through evaluation of different load volumes for a fixed membrane chromatography module in dynamic simulation [33]. MATLAB's shape-preserving cubic spline interpolation then generates the surrogate function, which can be validated against the original finite element method simulation through root-mean-square error (RMSE) analysis [33]. The accuracy of this approximation is controlled through point density in the library, with one point every 1L load/L membrane achieving an RMSE of less than 10⁻³ [33].

Optimization Problem Formulation

The multi-objective optimization problem for capture chromatography typically involves balancing competing performance indicators such as Cost of Goods (COG) and Process Time (Pt). The surrogate framework combines these into a single objective function through weighted sum scalarization:

minₓ f(x) = Wcog × (COG(x) - minCOG)/minCOG + (1 - Wcog) × (Pt(x) - minPt)/minPt

where x = (Vmedia, Vload) represents the decision variables (chromatography media volume and load volume), bounded by feasible operating ranges [33]. The weight parameter Wcog (0-1) allows users to adjust the relative importance of cost versus time considerations based on specific production requirements.

The optimization variables present different challenges based on process specifications. Media volume (Vmedia) can be treated as continuous for custom-made chromatography modules or discrete for standard-sized equipment (e.g., multiples of 1.6L) [33]. Similarly, load volume (Vload) can be continuous with continuous feed supply or discrete with fixed batch volumes (e.g., increments of 50L) [33]. This flexibility enables the framework to address integer, continuous, and mixed-integer optimization problems commonly encountered in industrial settings.

Experimental Protocols for Capture Chromatography

Protein A Affinity Chromatography Protocol

Protein A affinity chromatography remains the gold standard for mAb capture due to its exceptional specificity for the Fc region of antibodies [32]. The following protocol outlines the standard procedure with recent improvements for aggregate removal:

Resin Preparation: Pack Protein A resin (e.g., MabSelect SuReLX) in a suitable chromatography column according to manufacturer specifications. For analytical-scale purifications using 96-well formats, use 15-30 μL of resin per sample [34]. Ensure the resin is equilibrated with at least 4 column volumes (CV) of equilibration buffer (20 mM sodium phosphate, 15 mM NaCl, pH 7.4) [31].

Sample Loading: Clarify cell culture fluid through centrifugation (4000×g, 40 min) and 0.2 μm filtration [31]. Adjust clarified harvest to pH 7.4 if necessary. Load the sample onto the equilibrated column at a flow rate of 1 mL/min for preparative scale, or incubate with resin in filter plates using orbital mixing (1250 RPM, 20 min, 8°C) for high-throughput applications [34]. Maintain appropriate residence time (typically 3.6-1.44 minutes) based on dynamic binding capacity requirements [31].

Washing: Remove unbound contaminants using 6 CV of wash buffer (10 mM EDTA, 1.5 M sodium chloride, 40 mM sodium phosphate, pH 7.4) [31]. For enhanced aggregate removal, incorporate 5% PEG with 500 mM calcium chloride or 750 mM sodium chloride in wash buffers [35].

Elution: Recover bound mAb using 10 CV of elution buffer (100 mM sodium citrate or 100 mM glycine, pH 3.0-3.3) [31] [34]. For improved aggregate separation, include 500 mM calcium chloride with 5% PEG in elution buffers [35]. Immediately neutralize eluted fractions with 1/10 volume of 1 M Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) or 2 M Tris to prevent antibody degradation [31] [34].

Cleaning and Storage: Clean the resin with 20% ethanol for storage, or use 20% ethanol with 100 mM NaOH for more rigorous cleaning where resin tolerance permits [36].

Cation-Exchange Chromatography Capture Protocol

As an alternative to Protein A chromatography, cation-exchange chromatography (CEX) offers cost advantages and high dynamic binding capacity (>100 g/L) [36]. The following protocol is optimized for mAb capture from clarified harvest:

Resin Selection and Preparation: Select high-capacity CEX resins such as Toyopearl GigaCap S-650M or Capto S [36]. Pack the resin according to manufacturer instructions and equilibrate with at least 4 CV of equilibration buffer (74 mM sodium acetate, pH 5.3, conductivity 4.5 mS/cm) [36].

Sample Conditioning and Loading: Adjust clarified harvest to pH 5.2±0.2 and conductivity 4.5±0.5 mS/cm through dilution or buffer exchange [36]. Load conditioned sample onto the equilibrated column, maintaining a residence time of 2-6 minutes based on binding capacity requirements [36]. Monitor flow-through for product breakthrough to optimize loading capacity.

Washing: Wash the column with 2-5 CV of equilibration buffer to remove unbound and weakly bound contaminants [36]. For additional impurity removal, incorporate a intermediate wash with equilibration buffer containing increased conductivity (e.g., +50-100 mM NaCl).

Elution: Elute bound mAb using a linear or step gradient of increasing salt concentration (0-120 mM NaCl in equilibration buffer) [36]. Determine optimal elution conditions through Design of Experiment (DOE) studies, typically targeting pH 5.2-5.5 and 110-120 mM NaCl for optimal yield and impurity clearance [36].

Cleaning and Regeneration: Clean with 1 M NaCl followed by 0.5-1.0 M NaOH, assessing resin stability to alkaline conditions for determination of cleaning cycle frequency [36].

Surrogate Model Development Protocol

Data Generation: Using the established chromatography protocols, systematically vary critical process parameters (e.g., media volume, load volume, residence time) across their feasible operating ranges [33]. For each parameter combination, perform the chromatography experiment or simulation to determine key performance indicators (yield, purity, COG, process time).

Library Construction: Compile the results into a structured database relating input parameters to output metrics [33]. For breakthrough curve simulation, generate yield values across a range of relative load values (e.g., 50-200 L load volume per unit membrane volume) with point density sufficient to achieve target accuracy (e.g., 1 point per 1L load/L membrane) [33].

Surrogate Function Implementation: Employ mathematical interpolation techniques (e.g., shape-preserving cubic spline interpolation in MATLAB) to create continuous functions approximating the relationship between input parameters and output metrics [33]. Validate surrogate model predictions against experimental data or full simulations for a verification set not used in model training.

Optimization Execution: Apply appropriate optimization algorithms (genetic algorithms, mixed-integer programming) to the surrogate models to identify optimal process conditions [33]. For multi-objective problems, utilize scalarization approaches or Pareto front generation to explore trade-offs between competing objectives.

Data Presentation and Analysis

Quantitative Performance Comparison

Table 1: Comparison of Chromatography Capture Methods for mAb Purification

| Parameter | Protein A Chromatography | Cation-Exchange Chromatography | Precipitation Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dynamic Binding Capacity | ≤40 g/L [36] | ≥90 g/L [36] | Variable, concentration-dependent [31] |

| Purity After Capture | >98% [32] | ≥95% HCP reduction [36] | Lower than chromatography [31] |

| Yield | High [31] | ≥95% [36] | High [31] |

| Cost Impact | High (resin cost $9,000-12,000/L) [36] | Moderate | Low [31] |

| Aggregate Removal | Limited without optimization [35] | Moderate | Variable [31] |

| Ligand Leaching | Yes (requires monitoring) [36] | No | No |

| Processing Time | Moderate | Moderate | Rapid [31] |

Table 2: Surrogate Optimization Performance in Chromatography Process Design

| Optimization Approach | Number of Function Evaluations | Computational Time | Accuracy | Application Scope |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Simulation | High | ~2 days for multi-objective problem [33] | Direct calculation | Limited by computational resources |

| Surrogate Optimization | Reduced by ~93% [33] | ~93% reduction [33] | RMSE <10⁻³ [33] | Broad, accessible for industrial applications |

| Genetic Algorithms | Very high | Extended computing time [33] | Does not guarantee optimal solution [33] | Comprehensive but computationally expensive |

| MATLAB Built-in Tools | Moderate | Reduced | High with proper implementation [33] | Flexible for integer, continuous, mixed-integer problems |

Enhanced Aggregate Removal Data

Recent advancements in Protein A chromatography have demonstrated significant improvements in aggregate removal through buffer modifications:

Additive Screening: The incorporation of 5% PEG with 500 mM calcium chloride in elution buffers reduces aggregate content from 20% to 3-4% in the elution pool [35]. This represents a 4-5 fold reduction in aggregates compared to standard Protein A elution.

Concentration Optimization: Evaluation of calcium chloride concentration (250 mM, 500 mM, 750 mM, 1 M) identified 500 mM as optimal for improving monomer-aggregate resolution [35]. Similarly, sodium chloride at 750 mM with 5% PEG demonstrates comparable efficacy [35].

Mechanistic Basis: Calcium chloride enhances separation by modifying hydrophobic interactions between antibodies and Protein A ligands, leading to improved selectivity without compromising product recovery [35].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for mAb Capture Chromatography

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Application | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Protein A Resins | Primary capture step for mAbs through Fc region binding | MabSelect SuReLX [31];耐碱型树脂 for enhanced cleaning [32] |

| Cation-Exchange Resins | High-capacity capture alternative to Protein A | Toyopearl GigaCap S-650M (≥100 g/L capacity) [36]; Capto S (75 g/L capacity) [36] |

| Chromatography Systems | Process-scale and analytical-scale purification | Äkta pure FPLC [31]; Andrew+机器人平台 for high-throughput screening [34] |

| Binding Buffers | Conditioned media for optimal antibody binding | 20 mM sodium phosphate, 15 mM NaCl, pH 7.4 (Protein A) [31]; 74 mM sodium acetate, pH 5.3 (CEX) [36] |

| Elution Buffers | Antibody recovery under mild denaturing conditions | 100 mM sodium citrate, pH 3.3 [31]; 100 mM glycine, pH 3.0 [34] |

| Additive Solutions | Enhance aggregate removal and resolution | 5% PEG with 500 mM CaCl₂ or 750 mM NaCl [35] |

| Neutralization Buffers | Stabilize antibodies after low-pH elution | 1 M Tris-HCl, pH 7.5 [34]; 2 M Tris [36] |

| Analysis Systems | Quality assessment of purified mAbs | ACQUITY UPLC with SEC columns [34]; Octet BLI for binding kinetics [37] |

Workflow Visualization

Surrogate Optimization Workflow for mAb Purification

Experimental mAb Capture Chromatography Process

The implementation of surrogate optimization approaches represents a paradigm shift in the design and optimization of capture chromatography processes for mAb purification. By achieving 93% reduction in computational time while maintaining accuracy, this methodology addresses a critical bottleneck in bioprocess development [33]. The combination of surrogate modeling with advanced chromatography techniques, including enhanced Protein A protocols for aggregate removal and high-capacity cation-exchange alternatives, provides a comprehensive toolkit for accelerating process development while maintaining product quality.

Future developments in this field will likely focus on the integration of machine learning algorithms with surrogate modeling for improved prediction accuracy, along with the continued advancement of chromatography resin technology to address capacity and cost challenges. As upstream titers continue to increase, placing additional pressure on downstream processing, these optimization methodologies will become increasingly essential for maintaining efficient, cost-effective biopharmaceutical manufacturing. The implementation of standardized, automated purification platforms with integrated analytics will further enhance the robustness and transferability of these approaches across the biopharmaceutical industry.