The Simplex Method in Optimization: From Geometric Foundations to Cutting-Edge Applications in Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of the simplex method, a cornerstone geometric algorithm for solving optimization problems.

The Simplex Method in Optimization: From Geometric Foundations to Cutting-Edge Applications in Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of the simplex method, a cornerstone geometric algorithm for solving optimization problems. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it covers the method's mathematical foundations in linear programming, its practical implementation across scientific domains, and advanced strategies for enhancing its performance. The content delves into modern applications, particularly in molecular shape similarity and virtual screening for drug discovery, and presents recent theoretical breakthroughs that explain the algorithm's remarkable real-world efficiency. A comparative analysis of simplex-based approaches against other optimization techniques is included to guide methodological selection.

The Geometry of Optimal Decisions: Unpacking the Simplex Method's Core Principles

Linear programming (LP) represents a cornerstone of mathematical optimization, providing a powerful framework for decision-making across scientific, industrial, and economic domains. This computational technique enables researchers to maximize or minimize a linear objective function subject to linear equality and inequality constraints [1]. The field originated from the pioneering work of George Dantzig, who developed the simplex method in 1947, creating both a practical algorithm and a rich geometric interpretation based on the properties of multidimensional polyhedra [2] [3]. For drug development professionals and researchers, understanding this historical trajectory reveals not only the mathematical foundations of optimization but also the conceptual bridge between abstract geometry and practical problem-solving. The evolution from Dantzig's original insight to contemporary implementations demonstrates how geometric principles—specifically the structure and navigation of simplex figures—have continuously informed optimization research and application.

The Genesis of Linear Programming

Historical Context and Predecessors

The mathematical foundations of linear programming predate Dantzig's work, with early contributions emerging from economic and statistical research. In 1827, Joseph Fourier published a method for solving systems of linear inequalities, establishing preliminary concepts for constraint handling [1]. During the late 1930s, Soviet mathematician Leonid Kantorovich and American economist Wassily Leontief independently explored practical applications of linear programming—Kantorovich focusing on manufacturing schedules and Leontief investigating economic applications [1]. Their groundbreaking work, though largely overlooked for years, eventually formed important precursors to Dantzig's more comprehensive framework.

World War II served as a critical catalyst for optimization methodologies, creating urgent demands for solutions to complex logistical challenges involving transportation, scheduling, and resource allocation [1]. Military planners needed mathematical tools to optimize resource deployment across global theaters, making optimal use of limited personnel, equipment, and industrial capacity. This wartime imperative directly motivated the formalization of linear programming as a distinct mathematical discipline.

George Dantzig and the Invention of the Simplex Method

In 1947, while working for the U.S. Air Force under Project SCOOP (Scientific Computation of Optimum Programs), George Dantzig formulated the general linear programming problem and developed the simplex method for its solution [3]. Dantzig's military affiliation initially limited public dissemination of his work, with his earliest publications appearing in 1951 [3]. The now-famous origin story recounts how Dantzig, as a graduate student at UC Berkeley in 1939, arrived late to a statistics class and copied two problems from the blackboard, believing them to be homework assignments [4]. These "homework" problems were actually famous unsolved problems in statistics, which Dantzig successfully solved, developing mathematical techniques that would later inform his simplex algorithm [4].

Dantzig's key insight was recognizing that linear programming problems with bounded solutions must attain their optimal values at vertices (extreme points) of the feasible region [2]. Rather than exhaustively evaluating all vertices—a computationally prohibitive approach—the simplex method navigates efficiently along edges of the polyhedron from one vertex to an adjacent one with improved objective function value until reaching the optimum [2]. This vertex-to-vertex navigation represents the geometric essence of the algorithm and establishes the fundamental connection between algebraic linear programming and polyhedral geometry.

Table: Key Historical Developments in Early Linear Programming

| Year | Contributor | Contribution | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1827 | Joseph Fourier | Method for solving linear inequalities | Early foundation for constraint handling |

| 1939 | Leonid Kantorovich | Manufacturing scheduling applications | First economic applications of LP concepts |

| 1939 | Wassily Leontief | Input-output economic models | Nobel Prize-winning economic applications |

| 1947 | George Dantzig | Simplex method formulation | First practical algorithm for solving LPs |

| 1947 | John von Neumann | Duality theory | Theoretical foundation for optimality conditions |

| 1951 | Dantzig, Orden, Wolfe | Generalized simplex method | First published description of simplex method |

The Simplex Method: Algorithmic Framework and Geometric Interpretation

Theoretical Foundations

The simplex method operates on linear programs in standard form, which can be expressed as maximizing cᵀx subject to Ax ≤ b and x ≥ 0, where x represents the decision variables, c defines the objective function coefficients, A is the constraint coefficient matrix, and b denotes the right-hand side constraint values [1]. Dantzig proved that if a linear program has a finite optimum, it exists at an extreme point of the feasible region [2]. This fundamental theorem provides the mathematical justification for the simplex method's vertex-hopping approach rather than searching the interior of the feasible region.

The algorithm proceeds through two main phases. In Phase I, the method identifies an initial basic feasible solution (extreme point) by solving an auxiliary linear program. Phase II then iteratively moves from the current vertex to an adjacent vertex with improved objective function value until no further improvement is possible, indicating optimality [2]. Each iteration involves selecting an entering variable (which defines the direction of movement along an edge) and a leaving variable (which maintains feasibility) through pivot operations [2].

Geometric Interpretation of the Simplex Algorithm

The geometric interpretation of the simplex method reveals its intimate connection with simplex figures and polyhedral geometry. The feasible region defined by the constraints Ax ≤ b, x ≥ 0 forms a convex polyhedron in n-dimensional space [1]. For a problem with n decision variables, each vertex of this polyhedron corresponds to a basic feasible solution where at least n constraints are binding.

The simplex algorithm navigates this polyhedron by moving along edges from one vertex to an adjacent one, with each edge representing a one-dimensional intersection of n-1 linearly independent constraints [2]. This geometric navigation can be visualized as moving from vertex to vertex along the edges of a multidimensional simplex figure, always following a path that improves the objective function.

Table: Components of the Simplex Method and Their Geometric Interpretations

| Algebraic Component | Geometric Interpretation | Role in Algorithm |

|---|---|---|

| Basic feasible solution | Vertex of polyhedron | Current solution at each iteration |

| Nonbasic variable | Binding constraint | Defines potential movement direction |

| Pivot operation | Movement along edge | Transitions to adjacent vertex |

| Reduced cost | Slope of objective function | Determines improving directions |

| Optimality condition | No improving adjacent vertices | Termination criterion |

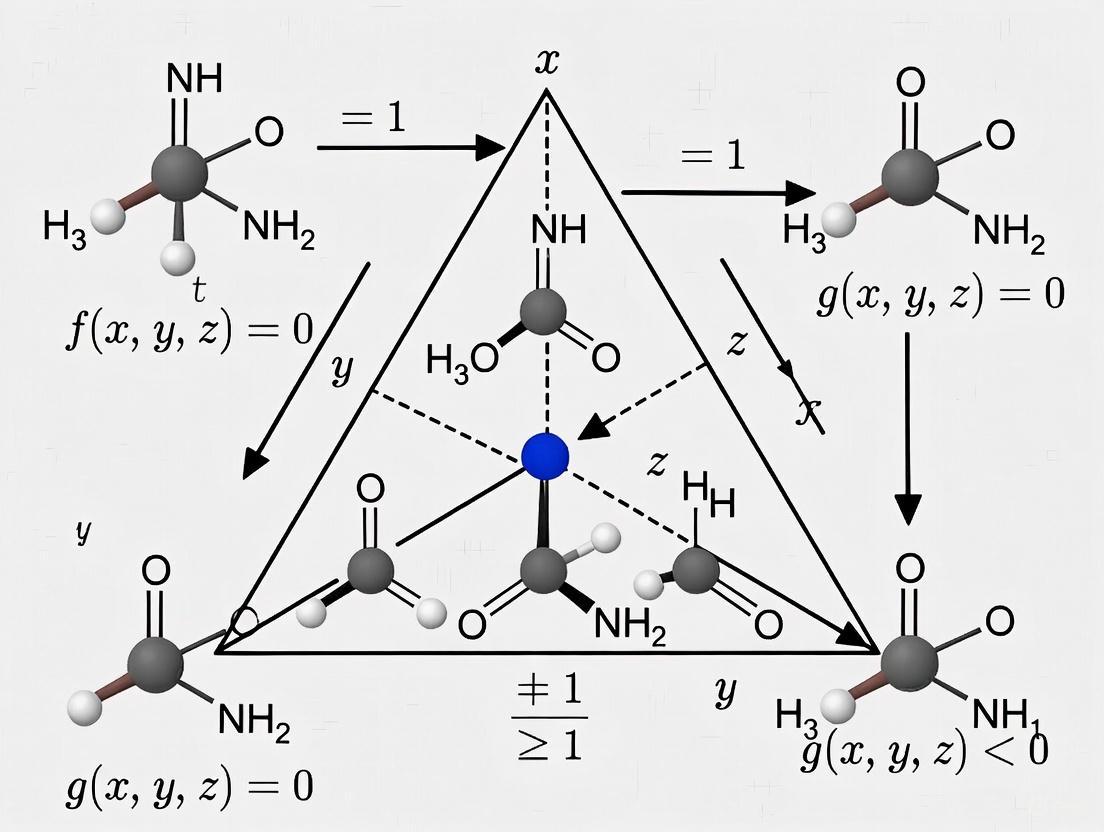

Diagram 1: Simplex Algorithm Vertex Navigation. The diagram illustrates the simplex method's path through a polyhedron's vertices, following edges that improve the objective function until reaching the optimal solution.

Experimental Protocol: Simplex Method Implementation

For researchers seeking to implement or analyze the simplex method, the following detailed protocol outlines the core computational procedure:

Problem Formulation: Convert the linear program to standard form: Maximize cᵀx subject to Ax ≤ b, x ≥ 0. Introduce slack variables to transform inequalities to equalities [5].

Initialization (Phase I): Construct the initial simplex tableau by:

- Adding slack variables to convert inequalities to equalities

- Setting up the augmented form [1 -cᵀ 0; 0 A I][z x s]ᵀ = [0 b]ᵀ, where s represents slack variables [1]

- Identifying an initial basic feasible solution by setting decision variables to zero and slack variables to b

Optimality Test: Check if all reduced costs (coefficients in the objective row) are non-positive. If yes, the current solution is optimal; otherwise, continue [5].

Pivot Selection:

Pivot Operation: Perform Gaussian elimination to make the entering variable basic and the leaving variable nonbasic, updating the entire tableau [2].

Iteration: Repeat steps 3-5 until optimality conditions are satisfied or unboundedness is detected.

This protocol provides the fundamental framework for simplex implementations, though production-grade solvers incorporate numerous enhancements for numerical stability and performance.

Evolution of Linear Programming Algorithms

Computational Complexity and the Simplex Method

Despite its remarkable practical efficiency, the simplex method exhibits theoretical computational limitations. In 1972, mathematicians demonstrated that the time required to complete the algorithm could rise exponentially with the number of constraints in worst-case scenarios [4]. These pathological cases force the algorithm to visit an exponential number of vertices before reaching the optimum, despite its generally efficient performance on practical problems.

The discrepancy between the simplex method's practical efficiency and its theoretical worst-case performance motivated fundamental questions about the nature of the algorithm. As Dantzig himself noted, the method appeared efficient in the "column geometry" but potentially inefficient in the "row geometry" [3]. This observation highlighted how the same mathematical procedure could exhibit dramatically different performance characteristics depending on the geometric perspective employed.

Interior Point Methods and Polynomial Complexity

A theoretical breakthrough occurred in 1979 when Leonid Khachiyan proved that linear programming problems could be solved in polynomial time using the ellipsoid method [1]. While theoretically significant, this approach proved impractical for computational implementation. The field transformed again in 1984 when Narendra Karmarkar introduced a revolutionary interior point method (IPM) that not only guaranteed polynomial-time complexity but also delivered competitive practical performance [1] [6].

Unlike the simplex method's geometric approach of navigating along exterior edges, interior point methods traverse through the interior of the feasible region [6]. This fundamental difference in geometric strategy avoids the worst-case combinatorial complexity of vertex enumeration. Interior point methods employ sophisticated mathematical techniques including barrier functions, Newton's method, and predictor-corrector steps to follow a central path through the feasible region toward the optimal solution [6].

Table: Comparison of Simplex and Interior Point Methods

| Characteristic | Simplex Method | Interior Point Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Geometric path | Vertex-to-vertex along edges | Through interior along central path |

| Theoretical complexity | Exponential worst-case | Polynomial worst-case |

| Practical performance | Excellent for most problems | Excellent for large, sparse problems |

| Solution characteristics | Exact at vertices | Approaches optimum asymptotically |

| Memory requirements | Moderate | Higher for Newton steps |

| Warm-start capability | Excellent | Limited |

Modern Hybrid Approaches and Recent Theoretical Advances

Contemporary linear programming solvers frequently employ hybrid strategies that leverage the complementary strengths of simplex and interior point methods. Interior point methods often efficiently solve the initial continuous relaxation, while simplex methods excel at reoptimization after adding constraints or during branch-and-bound procedures in mixed-integer programming [6].

Recent theoretical work has addressed long-standing questions about the simplex method's performance. In 2001, Spielman and Teng demonstrated that incorporating slight randomness into the algorithm could eliminate exponential worst-case behavior, establishing that the simplex method has polynomial complexity under smoothed analysis [4]. More recently, Huiberts and Bach (2024) further refined this analysis, providing stronger mathematical justification for the method's observed efficiency and establishing tighter bounds on its expected runtime [4].

These theoretical advances confirm that the exponential worst-case scenarios rarely manifest in practice, explaining why the simplex method remains competitive decades after its invention. As Huiberts noted, "It has always run fast, and nobody's seen it not be fast" [4].

Diagram 2: Linear Programming Algorithm Pathways. The diagram illustrates the divergent geometric strategies of simplex and interior point methods for solving linear programs.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Linear Programming Research Reagents

Table: Essential Methodological Components in Linear Programming Research

| Component | Function | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Simplex Tableau | Matrix representation of LP in canonical form | Foundation for pivot operations; stored as [1 -cᵀ 0; 0 A b] [2] |

| Slack/Surplus Variables | Convert inequalities to equalities | Non-negative variables added to ≤ constraints or subtracted from ≥ constraints [2] |

| Basis Factorization | Maintain LU factorization of basic columns | Critical for numerical stability in production solvers [2] |

| Pivot Selection Rules | Determine entering and leaving variables | Choices include Dantzig's rule (max reduced cost), steepest edge, Devex [2] |

| Barrier Parameter | Control proximity to central path in IPMs | Dynamically updated to balance optimality and feasibility [6] |

| Predictor-Corrector | Accelerate convergence in IPMs | Combines affine-scaling and centering steps [6] |

| Branch-and-Bound | Solve integer programming extensions | Tree search with LP relaxations at nodes [6] |

Applications in Scientific and Pharmaceutical Research

The geometric principles underlying linear programming have found diverse applications across scientific domains, particularly in drug development and pharmaceutical research. While the mathematical formalism remains consistent, the interpretation of the simplex figure and optimization landscape varies by application.

In pharmaceutical manufacturing, linear programming optimizes production schedules subject to constraints including equipment availability, raw material inventories, and regulatory compliance requirements [7]. The feasible region polyhedron represents all feasible production plans, with vertices corresponding to extreme operating regimes. Navigation along edges corresponds to reallocating resources between different product lines or adjusting batch sizes.

Drug discovery pipelines employ optimization techniques for resource allocation across multiple research stages, from target identification through clinical trials [7]. Linear programming models balance tradeoffs between research investment, timeline constraints, and success probabilities across parallel development tracks. The geometric interpretation involves navigating a high-dimensional feasible region where each dimension represents resource allocation to different research programs.

In biomedical data analysis, linear programming formulations support experimental design optimization, determining the most informative measurements subject to budget, time, and technological constraints [7]. The vertices of the feasible polyhedron represent extreme experimental configurations, with the simplex method identifying the optimal design through systematic exploration of these possibilities.

The historical trajectory from Dantzig's geometric insight to modern linear programming embodies the enduring significance of simplex figures in optimization research. Dantzig's fundamental observation—that optimal solutions reside at vertices of feasible polyhedra and can be found by efficient edge navigation—established a geometric paradigm that has influenced optimization theory and practice for nearly eight decades. The subsequent evolution of interior point methods, with their alternative geometric strategy of traversing the interior region, expanded the conceptual framework while further demonstrating the profound connection between geometry and computation in mathematical optimization.

For contemporary researchers, particularly in scientific and pharmaceutical domains, understanding this geometric foundation provides more than historical context—it offers intuitive insight into problem structure, algorithm selection, and result interpretation. The simplex figure remains a powerful conceptual model for reasoning about constraint interactions and solution pathways in high-dimensional decision spaces. As optimization challenges grow increasingly complex in drug development and scientific research, the geometric principles established in linear programming's origins continue to inform new methodological developments and applications.

This technical guide examines the fundamental role of the simplex geometric figure in optimization research, focusing on its application in the simplex method for linear programming. We explore how multi-dimensional polyhedra form the solution space for constrained optimization problems, with vertices representing potential solutions that algorithms navigate to identify optimal points. Within the broader context of simplex geometry research, this whitepaper provides researchers and drug development professionals with advanced visualization techniques, quantitative frameworks, and experimental protocols for implementing these methods in complex scientific optimization challenges. The geometric interpretation of solution spaces continues to enable breakthroughs across multiple disciplines, from operational research to pharmaceutical development.

The simplex method, developed by George Dantzig in 1947, represents one of the most significant breakthroughs in mathematical optimization [4]. Its enduring utility across diverse fields—from supply chain management to drug development—stems from its elegant geometric foundation. At its core, the method transforms complex allocation problems with numerous variables and constraints into navigable geometric structures [8].

In linear programming, the solution space defined by multiple constraints forms a convex polytope in n-dimensional space [9]. This polyhedron, known as a simplex in specific contexts, possesses critical properties that enable efficient optimization: its vertices (or extreme points) represent potential solutions, and the optimal solution always resides at one of these vertices [9]. For researchers and scientists, this geometric interpretation provides both computational efficiency and intuitive understanding of complex optimization landscapes.

Recent theoretical advances continue to refine our understanding of simplex geometry. In 2025, Huiberts and Bach published work significantly advancing our theoretical understanding of the simplex method's efficiency, providing stronger mathematical justification for its polynomial-time performance in practice [4]. This research builds upon the landmark 2001 work by Spielman and Teng, which demonstrated how introducing randomness prevents worst-case exponential runtime scenarios [4].

Geometric Foundations of Linear Programming

Formulating the Solution Space as a Polyhedron

Linear programming problems begin with an objective function to maximize or minimize, subject to multiple linear constraints. Geometrically, each constraint defines a half-space in n-dimensional space, and the intersection of these half-spaces forms a convex polytope [9]. In the context of the simplex method, this polytope represents all feasible solutions that satisfy the constraints.

For a problem with n decision variables, the solution space exists in n-dimensional space, with each constraint adding a bounding hyperplane [9]. The region where all constraints overlap—the feasible region—takes the form of a convex polyhedron. The term "simplex" in the algorithm's name refers to this geometric structure, though technically the solution space is a polyhedron that the algorithm navigates via its vertices.

Table: Geometric Interpretation of Linear Programming Elements

| Algebraic Element | Geometric Interpretation | Dimension |

|---|---|---|

| Decision variable | Axis in coordinate system | 1D |

| Linear constraint | Hyperplane | (n-1)D |

| Feasible solution | Point within polyhedron | 0D |

| Optimal solution | Vertex of polyhedron | 0D |

| Objective function | Direction in space | 1D |

Extreme Points and Optimal Solutions

The fundamental theorem of linear programming states that if an optimal solution exists, it must occur at one of the extreme points (vertices) of the polyhedral solution space [9]. This crucial insight reduces the optimization problem from searching an infinite solution space to examining a finite number of candidate points.

Each vertex represents a potential solution where the system of constraints is tightly bound. In practical terms, for a problem with n variables, a vertex occurs where at least n constraints are exactly satisfied [9]. The simplex method leverages this principle by systematically moving from vertex to adjacent vertex along the edges of the polyhedron, improving the objective function with each transition until no better adjacent vertex can be found.

Mathematical Formalization and Standardization

Standard Maximization Problem Formulation

To implement the simplex method algorithmically, linear programs must first be converted to standard form. For a maximization problem with n variables and m constraints, the canonical representation becomes:

Maximize: ( \bm c^\intercal \bm x ) Subject to: ( A\bm x \le \bm b ) And: ( \bm x \ge 0 ) [9]

Here, ( \bm x ) represents the vector of decision variables, ( \bm c ) contains the coefficients of the objective function, A is the matrix of constraint coefficients, and ( \bm b ) is the vector of right-hand-side values for the constraints.

Incorporating Slack Variables

To transform inequality constraints into equalities—a requirement for the simplex algorithm—slack variables are introduced [10]. For each "less than or equal to" constraint, a slack variable is added to represent the difference between the left-hand and right-hand sides. This converts the constraint system to equality form:

( A\bm x + \bm s = \bm b ), where ( \bm s \ge 0 ) [8]

These slack variables have profound geometric significance: at any vertex of the polyhedron, the non-basic variables (those set to zero) correspond to the constraints that are binding at that point, while basic variables (including slack variables) indicate which constraints have "slack" or are not fully utilized [8].

Table: Variable Types and Their Geometric Significance

| Variable Type | Geometric Interpretation | Algorithmic Role |

|---|---|---|

| Decision variable | Coordinate in solution space | Part of solution vector |

| Slack variable | Distance from hyperplane | Indicates constraint activity |

| Basic variable | Non-zero at current vertex | In solution basis |

| Non-basic variable | Zero at current vertex | Defines moving direction |

The Simplex Algorithm: A Geometric Navigation Process

Algorithmic Steps as Geometric Operations

The simplex method can be conceptualized as a structured walk along the edges of the polyhedral solution space [9]. At each vertex, the algorithm examines adjacent vertices reachable through single edge transitions and moves to one that improves the objective function. This process continues until no adjacent vertex offers improvement, indicating an optimal solution has been found.

The algorithm implementation involves these key steps:

- Initialization: Identify a starting vertex of the polyhedron [10]

- Optimality Check: Evaluate whether moving to adjacent vertices can improve the objective function [10]

- Pivot Operation: Move to an adjacent vertex along an edge of the polyhedron [10]

- Termination: When no improving adjacent vertices exist, the current vertex is optimal [10]

Visualizing the Navigation Process

The following diagram illustrates the simplex algorithm's path through a polyhedral solution space:

This visualization captures the simplex method's greedy approach to navigating the solution space, moving from vertex to vertex along edges that improve the objective function until reaching the optimal solution.

Computational Considerations and Recent Advances

Complexity Analysis and worst-case performance

While the simplex method performs efficiently in practice, theoretical analysis has revealed potential exponential worst-case runtime as the number of constraints increases [4]. This discrepancy between observed performance and theoretical worst-case scenarios long represented a fundamental puzzle in optimization theory.

In 1972, mathematicians established that the time required for the simplex method could grow exponentially with the number of constraints in worst-case scenarios [4]. This contrasted sharply with the method's consistently efficient performance on real-world problems, creating a significant theoretical challenge.

Smoothed Analysis and Modern Theoretical Frameworks

A breakthrough came in 2001 when Spielman and Teng introduced "smoothed analysis," demonstrating that with minimal randomization, the simplex method's runtime becomes polynomial in the number of constraints [4]. Their work showed that the exponential worst-case scenarios were exceptionally rare in practice.

The most recent advances by Huiberts and Bach further refine this understanding, providing stronger bounds on performance and demonstrating that their approach "cannot go any faster than the value they obtained" [4]. According to Heiko Röglin, a computer scientist at the University of Bonn, this work offers "the first really convincing explanation for the method's practical efficiency" [4].

Table: Evolution of Simplex Method Complexity Analysis

| Year | Researchers | Contribution | Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1947 | George Dantzig | Simplex Algorithm | Foundational method |

| 1972 | Klee & Minty | Exponential worst-case | Theoretical limitation identified |

| 2001 | Spielman & Teng | Smoothed analysis | Polynomial time with randomization |

| 2025 | Huiberts & Bach | Optimal bounds | Theoretical practice efficiency gap closed |

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Methodological Components

For researchers implementing simplex-based optimization, the following components constitute essential methodological tools:

Linear Programming Formulation Tools: Software for converting real-world problems into standard linear programming form (e.g., CPLEX, Gurobi) enables precise constraint and objective function specification [8].

Simplex Algorithm Implementations: Both primal and dual simplex variants provide computational engines for navigating polyhedral solution spaces, with commercial and open-source options available [10].

Slack Variable Management Systems: Methodologies for tracking constraint activity through slack variables provide crucial information about which constraints bind at each vertex [8].

Pivot Selection Heuristics: Rules for selecting entering and leaving variables during pivot operations significantly impact algorithm performance, with various strategies available [10].

Termination Detection Protocols: Methods for identifying optimal solutions, including cycling prevention mechanisms, ensure algorithm reliability [10].

Experimental Protocol for Simplex-Based Optimization

Problem Formulation and Standardization

Objective Function Definition: Formalize the optimization target as a linear function of decision variables. For drug development applications, this might represent cost minimization or efficacy maximization [11].

Constraint Identification: Enumerate all linear constraints defining feasible solutions, including resource limitations, thermodynamic boundaries, or biochemical requirements.

Standard Form Conversion: Introduce slack variables to transform inequalities to equalities, creating the augmented system ( A\bm x + \bm s = \bm b ) [10].

Initial Basis Selection: Identify an initial vertex of the solution polyhedron to begin the optimization process.

Algorithm Execution and Solution Verification

Iterative Pivot Operations: Systematically move from vertex to adjacent vertex, improving the objective function with each transition [10].

Optimality Verification: Confirm that no adjacent vertex offers objective function improvement, ensuring true optimality [10].

Solution Interpretation: Map the mathematical solution back to the original problem context, identifying active constraints and sensitivity information.

Validation and Sensitivity Analysis: Evaluate solution robustness to parameter variations and validate against known test cases or through simulation.

The following workflow diagram illustrates the complete experimental protocol:

The geometric interpretation of the simplex method as navigation through a polyhedral solution space continues to yield theoretical insights and practical applications across multiple disciplines. Recent advances in understanding the algorithm's computational complexity have strengthened its theoretical foundation while confirming its empirical efficiency.

For drug development professionals and researchers, simplex-based optimization provides a robust framework for addressing complex resource allocation, process optimization, and experimental design challenges. The method's ability to efficiently handle high-dimensional problems with numerous constraints makes it particularly valuable in data-rich research environments.

Future research directions include developing hybrid approaches that combine simplex methods with other optimization techniques, extending applications to non-linear domains through piecewise linear approximation, and leveraging increased computational power to address previously intractable problem scales. The continued refinement of simplex-based methodologies promises to enhance optimization capabilities across scientific domains, maintaining the approach's relevance in an increasingly data-driven research landscape.

The simplex method, developed by George Dantzig in 1947, represents a cornerstone of mathematical optimization whose geometric interpretation continues to inform contemporary research [4] [2]. This algorithm addresses linear programming problems—optimizing a linear objective function subject to linear equality and inequality constraints—which emerge across fields ranging from logistics to pharmaceutical development [12]. The method's name derives from the geometric concept of a simplex, the simplest possible polytope in any given space, though the algorithm actually operates on simplicial cones [2]. At its core, the simplex method implements a elegant geometric principle: it navigates along the edges of the feasible region polytope, moving from vertex to adjacent vertex, until an optimal solution is located [2] [13]. This pivoting mechanism along the feasible region's edges embodies the algorithm's fundamental operation and provides the theoretical framework for understanding its convergence properties [4].

Recent theoretical advances have illuminated why this geometric traversal proves so efficient in practice. While worst-case scenarios suggested exponential time complexity, Bach and Huiberts (2024) demonstrated that with appropriate randomization, the number of pivoting steps grows only polynomially with the number of constraints [4]. This work builds upon the landmark 2001 study by Spielman and Teng, which first established that introducing minimal randomness prevents the pathological cases that could force the algorithm to traverse an exponential number of edges [4]. For the research community, these findings validate the observed efficiency of the simplex method and reinforce the geometric perspective as essential to understanding its behavior in both theoretical and applied contexts.

Mathematical Foundations and Geometric Interpretation

Formal Problem Specification and Standard Form

The simplex algorithm addresses linear programs in standard form, which can be expressed as:

- Maximize $c^Tx$

- Subject to $Ax \leq b$ and $x \geq 0$

where $c$ is the coefficient vector of the objective function, $A$ is the constraint matrix, $b$ is the right-hand-side vector of constraints, and $x$ is the vector of decision variables [13]. Conversion to this standard form involves introducing slack variables to transform inequality constraints into equalities, ensuring all variables remain non-negative [2] [10]. Each variable assignment corresponds to a point in n-dimensional space, while the constraints collectively define a convex polytope representing the feasible region [2].

Geometric Representation of the Feasible Region

The feasible region $\{x \mid Ax \leq b, x \geq 0\}$ forms a convex polyhedron in n-dimensional space [13]. The fundamental theorem of linear programming states that if an optimal solution exists, it must occur at at least one vertex (extreme point) of this polyhedron [2]. This geometric insight dramatically reduces the search space from infinitely many points to a finite set of vertices. The simplex method exploits this principle by systematically exploring these vertices through edge traversal [13].

Table 1: Geometric Terminology in Linear Programming

| Geometric Concept | Algebraic Equivalent | Role in Optimization |

|---|---|---|

| Vertex | Basic feasible solution | Candidate optimal solution |

| Edge | Direction between adjacent basic solutions | Pivoting pathway |

| Facet | Linear constraint | Boundary of feasible region |

| Polytope | Feasible region | Set of all possible solutions |

The Pivoting Operation as Geometric Movement

Pivoting constitutes the fundamental operation that enables movement along the polytope's edges [2]. Algebraically, pivoting exchanges a basic variable (one currently in the solution) with a nonbasic variable (currently zero), effectively moving from one basic feasible solution to an adjacent one [2] [13]. Geometrically, this exchange corresponds to moving from one vertex to an adjacent vertex along a connecting edge [2]. The algorithm selects the entering variable based on its potential to improve the objective function, typically choosing the most negative reduced cost coefficient [10]. The leaving variable is determined by the minimum ratio test, which ensures the next solution remains feasible and lands exactly at the adjacent vertex [2].

The following diagram illustrates this pivoting process along the edges of a three-dimensional polyhedron:

Algorithmic Implementation and Computational Methodology

The simplex method begins by converting inequality constraints to equalities through the introduction of slack variables [13]. For each constraint $a{i1}x1 + a{i2}x2 + ... + a{in}xn \leq bi$, we add a slack variable $si \geq 0$ to create the equality $a{i1}x1 + ... + a{in}xn + si = bi$ [2]. These slack variables transform the constraint matrix A into an augmented form, enabling the algebraic operations necessary for pivoting [13]. The initial basic feasible solution typically sets all original variables to zero and the slack variables to their corresponding right-hand-side values, which corresponds geometrically to the origin point in the feasible region [10].

Tableau Representation and Pivot Selection

The simplex tableau provides a structured representation that organizes all necessary information for executing the algorithm [2] [10]. This matrix representation includes:

- The objective function coefficients

- The constraint matrix with slack variables

- The right-hand-side values

- The current objective function value

Table 2: Simplex Tableau Structure

| Basic Variables | x₁ | ... | xₙ | s₁ | ... | sₘ | Solution |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Objective Row | c₁ | ... | cₙ | 0 | ... | 0 | Constant |

| Constraint Rows | A matrix columns | Identity matrix | b values |

The pivot selection process follows a deterministic procedure [10]:

- Entering variable: Identify the nonbasic variable with the most negative coefficient in the objective row (for maximization problems)

- Leaving variable: For the pivot column selected, compute the ratios of the solution column to the corresponding positive entries in the pivot column, selecting the variable with the minimum ratio

- Pivot element: The intersection of the pivot column and pivot row

Pivoting Operations and Termination Conditions

The actual pivoting operation employs elementary row operations to transform the tableau [2]:

- Normalize the pivot row by dividing by the pivot element

- Eliminate all other entries in the pivot column using the normalized pivot row

- Update the basis representation to reflect the variable exchange

The algorithm terminates when no negative reduced costs remain in the objective row (for maximization), indicating optimality [10]. Alternative termination conditions handle special cases: unbounded solutions occur when no positive denominators exist in the ratio test, and degeneracy arises when multiple bases represent the same vertex [2].

The following diagram illustrates the complete simplex algorithm workflow:

Experimental Protocols and Computational Analysis

Benchmark Problems and Performance Metrics

Research into simplex method performance employs standardized benchmark problems to evaluate pivoting efficiency [4]. These benchmarks typically include:

- Netlib problems: A collection of real-world linear programming problems

- Randomly generated problems: Systems with known properties but random coefficients

- Pathological constructions: Specifically designed problems that challenge the algorithm

Performance analysis focuses on two key metrics: iteration count (number of pivots) and computational time [4]. Theoretical analysis distinguishes between worst-case complexity (exponential for certain deterministic pivot rules) and average-case performance (typically polynomial with appropriate randomization) [4].

Randomized Pivoting Rules

Recent theoretical advances incorporate randomization to avoid exponential worst-case scenarios [4]. The 2001 Spielman-Teng framework introduced smoothed analysis, showing that with tiny random perturbations, the expected number of pivoting steps becomes polynomial in the problem dimension [4]. The 2024 breakthrough by Bach and Huiberts further refined this approach, establishing tighter bounds on expected performance and demonstrating that their algorithm cannot outperform these established limits [4].

Table 3: Pivoting Rule Performance Characteristics

| Pivoting Rule | Worst-Case Complexity | Practical Efficiency | Theoretical Guarantees |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dantzig's Rule | Exponential | Excellent | None |

| Bland's Rule | Exponential | Poor | Prevents cycling |

| Steepest Edge | Exponential | Very Good | None |

| Randomized | Exponential | Good | Polynomial expected |

Applications in Scientific and Pharmaceutical Research

Pharmaceutical Formulation Optimization

The simplex method finds particularly valuable applications in pharmaceutical formulation development, where researchers must optimize complex mixtures of components subject to multiple constraints [12] [14]. The simplex centroid design represents a specialized experimental design that efficiently explores mixture compositions while maintaining the constraint that all components sum to a constant (typically 100%) [12]. In a 2022 study of methylphenidate fast-dissolving films, researchers employed a simplex centroid design to optimize the effects of independent variables including hydroxypropyl methyl cellulose (HPMC) E5, HPMC E15, and maltodextrin on critical responses such as drug release percentage, disintegration time, and tensile strength [12].

The experimental protocol for pharmaceutical optimization typically involves:

- Factor identification: Selecting the independent variables (excipient ratios, processing parameters)

- Constraint specification: Defining feasible ranges for each factor

- Experimental design: Generating sample points using simplex-based designs

- Response measurement: Quantifying performance characteristics

- Model fitting: Developing regression models relating factors to responses

- Optimization: Applying the simplex method to identify the optimal formulation [12]

Research Reagent Solutions and Computational Tools

Table 4: Essential Research Materials for Simplex Method Applications

| Research Reagent | Function in Optimization | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| HPMC E5/E15 | Polymer matrix forming agent | Pharmaceutical film formulation [12] |

| Maltodextrin | Film-forming polymer and disintegrant | Rapid-dissolve drug delivery systems [12] |

| Simplex Centroid Design | Experimental design for mixture variables | Efficient exploration of formulation space [12] |

| Multiple Regression Analysis | Modeling factor-response relationships | Building predictive models for optimization [12] |

| Linear Programming Software | Implementing simplex algorithm | Solving constrained optimization problems [4] |

Advanced Research Applications

Beyond traditional linear programming, simplex-based methodologies continue to enable advances across scientific domains. In antenna design, simplex predictors facilitate globalized parameter tuning using regression models that dramatically reduce computational expenses compared to conventional approaches [11]. The geometrical principles underlying the simplex method have also inspired specialized optimization techniques like the Nelder-Mead simplex method for parameter estimation in nonlinear systems [14]. These applications demonstrate how the core geometrical concepts of vertex-based search and edge traversal continue to inform contemporary computational science.

The geometrical interpretation of pivoting along the feasible region's edges provides not only an intuitive understanding of the simplex method but also a powerful framework for theoretical analysis and algorithmic improvement [4] [2]. Recent theoretical breakthroughs have substantially closed the gap between observed efficiency and worst-case predictions, offering mathematical justification for the method's practical success [4]. For the research community, these advances reinforce the value of geometrical perspectives in optimization algorithm design.

Future research directions include the pursuit of strongly polynomial algorithms, development of hybrid methods combining simplex with interior point approaches [6], and extension of simplex-based methodologies to non-linear and integer programming problems [11]. The continuing evolution of hardware architectures also prompts investigation of parallel and distributed simplex implementations capable of leveraging modern computational infrastructure. Through these ongoing research endeavors, the geometrical principles of edge traversal and vertex hopping continue to inform the advancement of optimization methodology across scientific and engineering disciplines.

In the realm of mathematical optimization, particularly within the geometric framework of the simplex method, the transformation of inequality constraints into equalities represents a fundamental conceptual and procedural breakthrough. Slack variables serve as the crucial mathematical device enabling this transformation, enabling solvers to navigate the polyhedral structures defined by constraint systems [15]. The introduction of these variables converts abstract inequalities into a working algebraic system that can be manipulated using standard linear algebraic techniques [16].

Within the context of simplex geometry, optimization problems define a feasible region known as a polytope—a geometric object with flat faces and edges in n-dimensional space [13]. The simplex method, developed by George Dantzig in 1947, operates by moving from vertex to vertex along the edges of this polytope, progressively improving the objective function value until an optimal solution is found [4] [17]. Slack variables are indispensable to this process, as they facilitate the creation of the initial vertex representation and enable the pivotal operations that drive the algorithm's progression through the solution space [13].

This technical guide examines the theoretical foundations, implementation methodologies, and research applications of slack variables within optimization frameworks, with particular attention to their role in defining and traversing simplex geometries.

Theoretical Foundations

Mathematical Formulation

Slack variables operate under a simple yet powerful principle: any inequality constraint can be transformed into an equality constraint through the introduction of a non-negative variable that "takes up the slack" between the two sides of the inequality [15]. Formally, for a constraint of the form:

[ a{i1}x1 + a{i2}x2 + \cdots + a{in}xn \leq b_i ]

We introduce a slack variable ( s_i \geq 0 ) such that:

[ a{i1}x1 + a{i2}x2 + \cdots + a{in}xn + si = bi ]

The slack variable ( si ) represents the margin by which the original inequality is satisfied [16]. When ( si = 0 ), the constraint is binding (active), meaning the solution lies exactly on the constraint boundary. When ( s_i > 0 ), the constraint is non-binding (inactive), indicating the solution lies strictly within the feasible region defined by that constraint [15].

For "greater than or equal to" constraints, a surplus variable (conceptually similar to a slack variable but subtracted) is used instead:

[ a{i1}x1 + a{i2}x2 + \cdots + a{in}xn - si = bi ]

with ( s_i \geq 0 ) [2].

Geometric Interpretation in Simplex Method

In the geometric framework of the simplex method, each slack variable corresponds to a dimension in the augmented solution space [13]. The feasible region defined by the original inequalities transforms into a polytope in this higher-dimensional space, with slack variables ensuring the solution set remains consistent with the original problem [15].

The introduction of slack variables enables the identification of basic feasible solutions—the vertices of the polytope—where each vertex corresponds to a scenario where certain variables (including slacks) are set to zero (non-basic) while the remaining variables (basic) are determined by solving the equality system [13]. As the simplex algorithm progresses from vertex to vertex along the edges of the polytope, it systematically exchanges basic and non-basic variables through pivot operations, continually improving the objective function value until optimality is reached [17].

Table: Variable States at Vertices of the Feasible Polytope

| Variable Type | Status at Vertex | Geometric Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Original variable | Non-basic (zero) | Vertex lies on constraint ( x_j = 0 ) |

| Original variable | Basic (non-zero) | Vertex lies in interior of ( x_j ) domain |

| Slack variable | Non-basic (zero) | Vertex lies on the corresponding constraint boundary |

| Slack variable | Basic (non-zero) | Vertex lies strictly inside the corresponding constraint |

Implementation Methodologies

Standard Form Conversion Protocol

The transformation of a linear program into standard form using slack variables follows a systematic protocol essential for simplex method implementation:

- Inequality Identification: Classify all constraints as either "≤" or "≥" inequalities [2].

- Slack/Surplus Introduction: For each "≤" constraint, add a non-negative slack variable; for each "≥" constraint, subtract a non-negative surplus variable [2] [15].

- Objective Function Adjustment: Assign zero coefficients to all slack/surplus variables in the objective function [13].

- Initial Dictionary Formation: Construct the initial simplex dictionary representing the equality system [13].

For a problem with ( m ) constraints and ( n ) original variables, this process expands the variable set to ( n + m ) dimensions, with the slack variables providing an initial basic feasible solution at the origin [13].

Simplex Tableau Construction

The simplex tableau provides a structured matrix representation of the linear program in standard form. For a problem with ( n ) decision variables and ( m ) inequality constraints, the initial tableau takes the form:

[ T = \begin{bmatrix} 0 & \bar{c}^T \ b & -\bar{A} \end{bmatrix} ]

where ( \bar{A} = [A \quad I_m] ) combines the original coefficient matrix ( A ) with an ( m \times m ) identity matrix representing slack variable coefficients, and ( \bar{c} \in \mathbb{R}^{n+m} ) contains the original objective coefficients padded with zeros for the slack variables [13].

Table: Initial Tableau Structure for Linear Program with Slack Variables

| Component | Dimension | Description |

|---|---|---|

| ( \bar{c} ) | ( 1 \times (n+m) ) | Extended cost vector with zeros for slacks |

| ( \bar{A} ) | ( m \times (n+m) ) | Augmented constraint matrix ([A | I_m]) |

| ( b ) | ( m \times 1 ) | Right-hand side constraint values |

| Basic variables | ( m ) elements | Initial basic variables (slack variables) |

| Non-basic variables | ( n ) elements | Initial non-basic variables (decision variables) |

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the complete workflow of the simplex method incorporating slack variables:

Advanced Research Applications

Interior Point Methods Comparison

While slack variables originated in the context of simplex methods, they remain relevant in modern optimization approaches. Interior point methods (IPMs), which emerged as competitive alternatives to the simplex method, also utilize slack variables but with different philosophical and algorithmic approaches [6].

Unlike simplex methods that navigate along the boundary of the feasible polytope, IPMs traverse through the interior of the feasible region, using slack variables to maintain feasibility while following central paths toward optimal solutions [6]. The integration of slack variables in decomposition algorithms, cutting plane schemes, and column generation techniques demonstrates their continuing relevance in advanced optimization research [6].

Table: Slack Variables in Optimization Algorithm Classes

| Algorithm Class | Role of Slack Variables | Solution Path | Theoretical Complexity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Simplex Method | Define initial basic feasible solution; enable vertex transitions | Polytope edges | Exponential worst-case; efficient in practice [4] |

| Interior Point Methods | Maintain feasibility in barrier functions; define central path | Interior of feasible region | Polynomial time [6] |

| Column Generation | Transform master problem constraints; price out new variables | Hybrid approach | Problem-dependent |

Absolute Value Reformulation

Beyond traditional linear programming, slack variables enable the reformulation of problems with non-linear elements. A particularly powerful application appears in isotonic L1 regression, where absolute value functions in the objective can be linearized through slack variable introduction [18].

For an objective term ( |yi - \mui| ), we can introduce two non-negative variables ( ui ) and ( vi ) such that:

[ |yi - \mui| = ui + vi ] [ yi - \mui = ui - vi ]

This reformulation transforms a non-smooth optimization problem into a linear program amenable to simplex-based solution techniques [18]. The approach demonstrates the flexibility of slack variables in extending the applicability of linear programming to problems with discontinuous derivatives or non-linear elements.

Recent Theoretical Advances

Recent research has addressed long-standing questions about the theoretical efficiency of the simplex method. While the algorithm has always performed efficiently in practice, theoretical worst-case scenarios exhibited exponential complexity [4]. Through the introduction of randomized pivot rules, researchers have established polynomial-time complexity bounds for the simplex method, with recent work by Bach and Huiberts achieving significantly lower runtime exponents than previously established [4].

These advances leverage the geometric interpretation of slack variables and their role in defining the polytope structure, providing stronger mathematical justification for the empirical efficiency observed in practical applications and helping to "calm some of the worries that people might have about relying on software available today that is based on the simplex method" [4].

Research Reagent Solutions

The experimental implementation of optimization algorithms requires specific computational components analogous to laboratory reagents. The following table details essential elements for working with slack variables in optimization research:

Table: Essential Research Reagents for Slack Variable Implementation

| Reagent Solution | Function | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| Inequality Converter | Transforms constraints to equalities | Automatic slack variable addition [16] |

| Tableau Constructor | Builds initial simplex dictionary | Matrix augmentation with identity submatrix [13] |

| Pivot Selector | Identifies entering/leaving variables | Ratio test implementation with Bland's Rule [13] |

| Basis Updater | Performs pivot operations | Gaussian elimination on tableau rows [2] |

| Feasibility Checker | Verifies solution admissibility | Non-negativity validation for basic variables [15] |

| Degeneracy Resolver | Prevents cycling in pivot sequence | Bland's Rule or perturbation methods [17] |

Slack variables represent both a practical computational tool and a profound conceptual bridge between algebraic inequalities and geometric representations in optimization. Their introduction enables the simplex method to navigate the vertices of feasible polytopes, transforming combinatorial search problems into systematic algebraic procedures. While algorithmic preferences have evolved to include interior point methods for certain problem classes, slack variables remain fundamental to the operationalization of linear programming concepts.

Recent theoretical advances in understanding the complexity of randomized simplex algorithms further validate the continued importance of these conceptual devices. For researchers and practitioners in fields ranging from pharmaceutical development to supply chain optimization, mastery of slack variables and their geometric interpretation provides essential insight into the inner workings of constrained optimization methodologies. As optimization challenges grow in scale and complexity in data science and AI applications, these foundational concepts continue to enable efficient solutions to real-world resource allocation problems.

In the broader context of research on simplex geometric figures in optimization, the simplex tableau emerges as the fundamental algebraic framework that operationalizes geometric intuition. The simplex method, pioneered by George Dantzig in 1947, revolutionized mathematical optimization by providing a systematic algorithm for solving linear programming problems [4] [17]. While the geometric interpretation visualizes solutions as vertices of a convex polyhedron, the tableau provides the computational machinery for navigating this geometric structure algebraically. This whitepaper establishes the simplex tableau as the critical bridge between the theoretical geometry of simplex figures and their practical application in optimization research.

Contemporary research continues to refine this decades-old algorithm. Recent work by Huiberts and Bach has further developed our theoretical understanding of why the simplex method performs efficiently in practice, addressing long-standing questions about its computational complexity [4]. For researchers and drug development professionals, mastering the tableau framework enables solutions to complex resource allocation problems, from laboratory resource management to clinical trial optimization, within a robust mathematical foundation that continues to evolve.

Theoretical Foundations: From Geometry to Algebra

The Geometric Basis of Simplex Method

The simplex method operates on a powerful geometric principle: the optimal solution to a linear programming problem always lies at a vertex (corner point) of the feasible region polyhedron [17]. This feasible region represents all possible solutions that satisfy the problem's constraints. In this geometric context, the algorithm systematically navigates from vertex to adjacent vertex along the edges of the polyhedron, improving the objective function at each step until reaching the optimal vertex [4] [17].

The term "simplex" in simplex method refers to this geometric navigation process through a polyhedral space, not directly to the algebraic tableau structure. However, the tableau provides the algebraic representation of this geometric journey. As researchers move through solution space, the tableau maintains the complete mathematical state of the current position, constraints, and improvement potential, effectively creating an algebraic map of the geometric territory.

Algebraic Formulation of Linear Programming

Linear programming problems seek to optimize a linear objective function subject to linear constraints. The standard formulation for maximization problems appears as:

- Maximize: $c^Tx$

- Subject to: $Ax ≤ b$

- And: $x ≥ 0$

Where $x$ represents the vector of decision variables, $c$ contains the coefficients of the objective function, $A$ is the matrix of constraint coefficients, and $b$ represents the right-hand side constraint values [17]. The simplex tableau transforms this formulation into an operational algebraic structure that enables systematic computation.

The Simplex Tableau: Structure and Components

Tableau Architecture

The simplex tableau organizes all critical problem information into a structured matrix format that tracks both the current solution and potential improvements [10]. This tabular representation transforms the abstract geometric navigation into a concrete computational procedure. The initial tableau structure encompasses several key components:

- Coefficient Matrix: Contains the coefficients of the constraints in standardized form

- Objective Function Row: Displays the coefficients of the objective function (often called the cost coefficients)

- Right-Hand Side Column: Contains the current solution values and constraint boundaries

- Basis Column: Identifies the basic variables that are currently in the solution

- Indicator Row: Shows the potential improvement from introducing non-basic variables (reduced costs)

Standard Form Conversion

Before constructing the initial tableau, problems must be converted to standard form through the introduction of slack variables. These variables transform inequality constraints into equalities by "taking up the slack" between resource usage and availability [10]. For a constraint $a{i1}x1 + a{i2}x2 + ... + a{in}xn ≤ bi$, we add a slack variable $si$ to create the equation $a{i1}x1 + a{i2}x2 + ... + a{in}xn + si = bi$, where $s_i ≥ 0$ [10]. This conversion is essential for the tableau to function as it creates the mathematical structure needed for the algebraic operations that follow.

Table 1: Problem Formulation Components for Simplex Tableau

| Component | Purpose | Example Representation |

|---|---|---|

| Decision Variables | Quantities to determine | $x1, x2, ..., x_n$ |

| Slack Variables | Convert inequalities to equations | $s1, s2, ..., s_m$ |

| Objective Function | Quantity to optimize | $Z = 3x1 + 2x2 + x_3$ |

| Constraints | Limitations on resources | $a{i1}x1 + ... + a{in}xn ≤ b_i$ |

| Non-negativity | Practical solution requirement | $xi ≥ 0, si ≥ 0$ |

Computational Methodology: Tableau Operations

Initial Tableau Construction

The step-by-step methodology for constructing the initial simplex tableau begins with the standardized linear programming problem [10]:

- Formulate the linear programming problem in standard maximization form with all constraints expressed as equations using slack variables

- Set up the initial tableau with columns for each decision variable, slack variable, the right-hand side values, and a basis column identifying the current basic variables

- Arrange the constraint coefficients in the main body of the tableau, ensuring that slack variables form an identity matrix within the constraint columns

- Place the objective function coefficients in the bottom row with signs reversed for standard maximization problems

- Initialize the solution by setting decision variables to zero and slack variables equal to the right-hand side constraint values

Pivoting Operations Methodology

The pivoting operation represents the algebraic equivalent of moving from one vertex to an adjacent vertex in the geometric interpretation of the simplex method. The experimental protocol for pivoting involves:

- Selecting the Entering Variable: Identify the non-basic variable that will enter the basis by choosing the most negative coefficient in the objective row (for maximization problems) [10]

- Calculating the Minimum Ratio: For each constraint row, compute the ratio of the right-hand side value to the corresponding coefficient in the entering variable column (ignoring negative or zero denominators)

- Identifying the Leaving Variable: Select the basic variable that will leave the basis by finding the smallest non-negative ratio from step 2 [10]

- Performing the Pivot Operation: Execute Gauss-Jordan elimination to make the entering variable a basic variable in the row of the leaving variable, which involves:

- Normalizing the pivot row so the pivot element becomes 1

- Eliminating all other entries in the pivot column through elementary row operations

This methodology continues iteratively until no negative coefficients remain in the objective row, indicating optimality [10].

Research Reagent Solutions for Tableau Experimentation

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools for Simplex Tableau Research

| Research Reagent | Function in Tableau Operations | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Linear Programming Solver Software (e.g., CPLEX, Gurobi) | Executes simplex algorithm operations at scale | Choose based on problem size, licensing, and integration needs |

| Matrix Operation Libraries | Performs pivot operations and basis updates | Ensure numerical stability for ill-conditioned problems |

| Sensitivity Analysis Tools | Measures solution robustness to parameter changes | Essential for drug development applications with uncertain parameters |

| Degeneracy Resolution Protocols | Prevents cycling in pathological cases | Implement Bland's rule or perturbation methods |

| Precision Arithmetic Systems | Maintains numerical accuracy in large problems | Critical for pharmaceutical applications requiring high precision |

Advanced Applications: Multi-objective Optimization in Drug Development

Extended Simplex Methodology for Multiple Objectives

Recent research has expanded the simplex methodology to address multi-objective optimization problems (MOLP) particularly relevant to drug development [19]. In pharmaceutical research, objectives typically conflict—such as maximizing efficacy while minimizing toxicity and cost—requiring sophisticated optimization approaches. The extended simplex technique for MOLP optimizes all objectives simultaneously through an enhanced tableau structure that maintains multiple objective functions within a unified framework [19].

The computational details of this approach involve:

- Formulating weighted objective functions that combine multiple criteria into a single composite objective

- Maintaining extended tableau structures that track all original objectives throughout the pivoting process

- Identifying efficient solutions that represent optimal trade-offs between competing objectives

- Generating Pareto-optimal frontiers that visualize the compromise solutions between objectives

Pharmaceutical Application Framework

The simplex tableau framework provides particular value in drug development applications through:

- Resource Allocation: Optimizing laboratory resources across multiple research projects

- Formulation Optimization: Balancing ingredient combinations to achieve desired drug properties

- Clinical Trial Design: Maximizing statistical power within budget and ethical constraints

- Supply Chain Management: Coordinating drug manufacturing and distribution networks

Comparative studies demonstrate that the simplex-based approach to multi-objective optimization provides "usefulness, practicality and strength" in handling these complex pharmaceutical problems with "reduced computational effort" compared to alternative methodologies like preemptive goal programming [19].

Workflow Visualization: Tableau Execution Pathway

The following diagram illustrates the complete computational workflow of the simplex tableau method, integrating both algebraic operations and their geometric interpretation:

Computational Analysis: Performance and Optimization

Complexity and Efficiency Metrics

The simplex method's performance has been extensively studied since its inception. While early theoretical work established that the algorithm could require exponential time in worst-case scenarios [4], practical experience demonstrated consistently efficient performance. As noted by researcher Sophie Huiberts, "It has always run fast, and nobody's seen it not be fast" [4]. This paradox between theoretical worst-case scenarios and practical efficiency has driven decades of research into the algorithm's computational properties.

Recent theoretical advances have substantially resolved this paradox. The 2001 work of Spielman and Teng demonstrated that with minimal randomization, the simplex method operates in polynomial time [4]. More recently, Bach and Huiberts have further refined these bounds, providing "stronger mathematical support" for the practical efficiency observed by users [4]. Their work establishes that "exponential complexity" scenarios do not materialize in practice, offering reassurance to researchers relying on simplex-based optimization.

Algorithmic Optimization Techniques

Table 3: Performance Optimization Strategies for Tableau Implementation

| Optimization Technique | Mechanism of Action | Impact on Computational Efficiency |

|---|---|---|

| Revised Simplex Method | Operates on inverse basis matrix rather than full tableau | Reduces memory usage and computation time for large, sparse problems |

| Bland's Rule Implementation | Prevents cycling by using deterministic variable selection | Eliminates infinite loops in degenerate problems |

| Hybrid Interior-Point Methods | Combines simplex with polynomial-time interior point approaches | Optimizes performance for very large-scale problems |

| Parallel Pivoting Operations | Distributes computational load across multiple processors | Accelerates solutions for extremely large-scale problems |

| Sparse Matrix Techniques | Efficiently stores and operates on matrices with many zero elements | Reduces memory requirements for constraint-rich problems |

The simplex tableau remains an indispensable framework for algebraic execution within the broader geometric context of optimization research. By providing a systematic computational structure for navigating the vertices of solution polyhedra, the tableau transforms geometric intuition into operational algorithms. Recent theoretical advances have strengthened our understanding of why this method performs efficiently in practice, addressing long-standing questions about its computational complexity [4].

For researchers and drug development professionals, mastery of the tableau framework enables solution of complex multi-objective optimization problems with conflicting constraints. The continued evolution of simplex methodologies—including extensions for multi-objective optimization and integration with interior-point methods—ensures this decades-old algorithm remains relevant for contemporary research challenges. As optimization problems in pharmaceutical research grow in scale and complexity, the simplex tableau provides a robust foundation for developing efficient, practical solutions that balance multiple competing objectives in drug discovery and development.

Beyond Theory: Practical Implementations of Simplex Optimization in Scientific Research

The Nelder-Mead simplex method, proposed by John Nelder and Roger Mead in 1965, represents a cornerstone algorithm in the landscape of numerical optimization techniques [20]. As a direct search method, it operates without requiring derivative information, making it particularly valuable for optimizing non-linear, non-convex, or noisy objective functions where gradient computation is impractical or impossible [20]. The algorithm's core principle revolves around the geometric concept of a simplex—a polytope of n+1 vertices in n-dimensional space—which iteratively adapts its shape and position within the search domain, effectively "rolling" downhill toward optimal regions [21].

Within the broader context of optimization research, simplex-based methodologies occupy a unique position between theoretical elegance and practical applicability. The simplex geometric figure serves as both navigation vehicle and exploration probe, enabling a balanced approach between global exploration and local refinement [22]. This paper presents a comprehensive technical examination of the Nelder-Mead algorithm, detailing its mathematical foundations, operational mechanics, implementation considerations, and contemporary applications—particularly in scientific domains such as drug development where empirical optimization is paramount.

Theoretical Foundations

The Simplex Geometry

In n-dimensional optimization space, the algorithm utilizes a simplex comprising n+1 vertices [20]. For a one-dimensional problem, this manifests as a line segment; in two dimensions, a triangle; in three dimensions, a tetrahedron; with analogous structures extending to higher dimensions [21]. The geometric flexibility of the simplex enables it to traverse diverse objective function landscapes through a series of transformations including reflection, expansion, contraction, and shrinkage operations.

The fundamental principle underlying the method's convergence is the systematic replacement of the worst-performing vertex in each iteration [23]. By continuously discarding the vertex with the highest objective function value (for minimization problems) and replacing it with a potentially better point, the simplex progressively migrates toward regions of improved fitness while adapting to the local topography of the search space [24].

Historical Context and Evolution

The Nelder-Mead technique emerged as an enhancement to the earlier simplex method of Spendley, Hext, and Himsworth [25]. Nearly six decades after its introduction, it remains a widely adopted approach in numerous scientific and engineering domains despite the subsequent development of more theoretically rigorous optimization methods [25]. Its enduring popularity stems from its conceptual simplicity, implementation straightforwardness, and generally effective performance on practical problems with moderate dimensionality [21].

Contemporary research has yielded improved understanding of the algorithm's convergence properties, with the ordered variant proposed by Lagarias et al. demonstrating superior theoretical characteristics compared to the original formulation [25]. Recent hybrid approaches have integrated the Nelder-Mead method with population-based global search techniques, addressing its limitation of potential convergence to local optima [22].

Algorithmic Framework

Core Operations

The Nelder-Mead algorithm progresses through iterative transformations of the working simplex, with each iteration comprising several systematic steps [20]:

Ordering: The simplex vertices are sorted by objective function value

- For minimization: ( f(\mathbf{x}1) \leq f(\mathbf{x}2) \leq \cdots \leq f(\mathbf{x}_{n+1}) )

- Define: ( \mathbf{x}1 ) (best), ( \mathbf{x}n ) (second-worst), ( \mathbf{x}_{n+1} ) (worst)

Centroid Calculation: Compute the centroid of all vertices except the worst: ( \mathbf{x}o = \frac{1}{n} \sum{i=1}^{n} \mathbf{x}_i )

Transformation: Apply one of four geometric operations based on objective function improvement

Reflection

Reflection generates a new candidate point by mirroring the worst vertex across the opposite face of the simplex [20]: [ \mathbf{x}r = \mathbf{x}o + \alpha(\mathbf{x}o - \mathbf{x}{n+1}) ] where ( \alpha > 0 ) is the reflection coefficient (typically ( \alpha = 1 )).

If ( f(\mathbf{x}1) \leq f(\mathbf{x}r) < f(\mathbf{x}n) ), the worst vertex ( \mathbf{x}{n+1} ) is replaced with ( \mathbf{x}_r ) and the iteration completes [20].

Expansion

When the reflection point represents a significant improvement (( f(\mathbf{x}r) < f(\mathbf{x}1) )), the algorithm attempts expansion to explore this promising direction more aggressively [20]: [ \mathbf{x}e = \mathbf{x}o + \gamma(\mathbf{x}r - \mathbf{x}o) ] where ( \gamma > 1 ) is the expansion coefficient (typically ( \gamma = 2 )).

If ( f(\mathbf{x}e) < f(\mathbf{x}r) ), ( \mathbf{x}{n+1} ) is replaced with ( \mathbf{x}e ); otherwise, ( \mathbf{x}_r ) is used [20].

Contraction

If the reflected point offers no improvement over the second-worst vertex (( f(\mathbf{x}r) \geq f(\mathbf{x}n) )), contraction is performed [20]:

Outside Contraction (when ( f(\mathbf{x}r) < f(\mathbf{x}{n+1}) )): [ \mathbf{x}c = \mathbf{x}o + \rho(\mathbf{x}r - \mathbf{x}o) ], where ( 0 < \rho \leq 0.5 )

Inside Contraction (when ( f(\mathbf{x}r) \geq f(\mathbf{x}{n+1}) )): [ \mathbf{x}c = \mathbf{x}o + \rho(\mathbf{x}{n+1} - \mathbf{x}o) ], where ( 0 < \rho \leq 0.5 )

If ( f(\mathbf{x}c) < \min(f(\mathbf{x}{n+1}), f(\mathbf{x}_r)) ), the worst vertex is replaced with the contracted point [20].

Shrink

If contraction fails to yield improvement, the simplex shrinks around the best vertex [20]: [ \mathbf{x}i = \mathbf{x}1 + \sigma(\mathbf{x}i - \mathbf{x}1) \quad \text{for } i = 2, \ldots, n+1 ] where ( 0 < \sigma < 1 ) is the shrinkage coefficient (typically ( \sigma = 0.5 )).

Table 1: Standard Parameter Values in Nelder-Mead Algorithm

| Parameter | Symbol | Standard Value | Alternative Scheme (Gao & Han) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reflection | α | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Expansion | γ | 2.0 | 1 + 2/n |

| Contraction | ρ | 0.5 | 0.75 - 1/(2n) |

| Shrink | σ | 0.5 | 1 - 1/n |

Algorithm Workflow Visualization

Diagram 1: Nelder-Mead Algorithm Workflow

Implementation Considerations

Initialization Strategies

The formation of the initial simplex significantly influences algorithm performance. A poorly conditioned initial simplex may lead to slow convergence or stagnation in local optima [23]. Common initialization approaches include:

Affine Simplexer: Constructs the initial simplex by applying affine transformations to the initial guess point [23]. For each dimension i, the corresponding vertex is generated as: [ \mathbf{x}i = \mathbf{x}0 + \mathbf{e}i \cdot b + a ] where ( \mathbf{e}i ) is the i-th unit vector, and a, b are carefully chosen constants.

MATLAB-style Initialization: The MATLAB implementation employs a specialized approach where:

- For non-zero parameters: add 5% of the parameter value

- For zero parameters: add a fixed constant (typically 0.00025) [23]

User-Defined Simplex: Advanced implementations allow complete user control over initial simplex generation, enabling domain-specific knowledge incorporation [23].

Termination Criteria

Appropriate termination conditions are essential for balancing computational efficiency with solution quality. Common convergence criteria include [23] [24]:

- Function Value Tolerance: The standard error of function values at simplex vertices falls below threshold g_tol