UV-Vis Light Sources and Detectors: A 2025 Technology Overview for Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the fundamental principles, current technologies, and practical applications of UV-Vis light sources and detectors, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

UV-Vis Light Sources and Detectors: A 2025 Technology Overview for Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the fundamental principles, current technologies, and practical applications of UV-Vis light sources and detectors, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. It explores the core mechanisms of light-matter interaction and electronic transitions, details the latest advancements in instrumentation for 2025, and presents established and emerging methodological applications in pharmaceutical analysis and environmental monitoring. The content further offers systematic troubleshooting guidance for common instrument and methodology issues and validates the technology's performance through comparative analysis with other spectroscopic techniques. By synthesizing foundational knowledge with cutting-edge applications and validation data, this guide serves as an essential resource for optimizing the use of UV-Vis spectroscopy in research and quality control environments.

The Principles of Light-Matter Interaction: From Electronic Transitions to Modern Instrument Design

Ultraviolet-Visible (UV-Vis) spectroscopy stands as a fundamental analytical technique in modern laboratories, providing critical insights into molecular structure and concentration. When molecules interact with light in the ultraviolet (200-400 nm) and visible (400-700 nm) regions of the electromagnetic spectrum, they undergo electronic transitions that form the basis for quantitative and qualitative analysis [1]. The Beer-Lambert Law provides the mathematical framework that links this light absorption to chemical properties, establishing a direct relationship between absorbance and analyte concentration [2] [3]. This technical guide explores these core principles within the context of contemporary UV-Vis light source and detector technology, with particular emphasis on applications relevant to researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Fundamental Principles of Electronic Transitions

When molecules absorb UV or visible light energy, electrons are promoted from ground-state molecular orbitals to higher-energy excited states. This process differs fundamentally from infrared spectroscopy, where energy absorption causes molecular vibrations rather than electronic transitions [1]. The energy of the absorbed photons must precisely match the energy gap between the involved molecular orbitals for the transition to occur.

The specific wavelengths absorbed reveal crucial information about molecular structure. For example, molecules with conjugated π systems absorb at longer wavelengths with higher intensity than those with isolated double bonds due to smaller HOMO-LUMO energy gaps [1].

Types of Electronic Transitions

Several distinct electronic transitions can occur depending on molecular structure and orbital types:

σ → σ* Transitions: These require the highest energy, typically occurring in the far UV region below 150 nm. For molecular hydrogen (H₂), this transition occurs at 111 nm, corresponding to an energy of 258 kcal/mol [1].

π → π* Transitions: These transitions occur in molecules with double bonds or conjugated systems. While ethene absorbs at 165 nm, extended conjugation significantly reduces the energy requirement, with 1,3-butadiene absorbing at 217 nm and 1,3,5-hexatriene at 258 nm [1].

n → π* Transitions: These involve the promotion of a non-bonding electron (often from oxygen, nitrogen, or sulfur atoms) to a π* antibonding orbital. These transitions are typically weaker and occur at longer wavelengths than π→π* transitions. In 4-methyl-3-penten-2-one, the n→π* transition appears as a weaker absorbance at 314 nm alongside the stronger π→π* transition at 236 nm [1].

Table 1: Characteristic Electronic Transitions in Organic Molecules

| Transition Type | Energy Requirement | Example Compound | Absorption Wavelength | Molar Absorptivity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| σ → σ* | Very High | Molecular Hydrogen (H₂) | 111 nm | High |

| π → π* | Moderate | Ethene | 165 nm | High |

| π → π* (Conjugated) | Lower | 1,3-Butadiene | 217 nm | High (~20,000) |

| n → π* | Lowest | 4-methyl-3-penten-2-one | 314 nm | Low (~100) |

Chromophores and Molecular Structure

Chromophores are molecular regions responsible for light absorption, typically consisting of π-electron systems or atoms with non-bonding electrons. The degree of conjugation dramatically affects absorption properties, with extended conjugation leading to absorption at longer wavelengths. Beta-carotene, with its system of 11 conjugated double bonds, absorbs blue light (around 470 nm) while transmitting red-yellow wavelengths, accounting for the characteristic orange color of carrots [1].

The Beer-Lambert Law: Foundation and Formulations

Historical Development

The relationship between light absorption and material properties has evolved through centuries of scientific inquiry:

1729: Pierre Bouguer discovered that light intensity decreases exponentially with path length through a medium, establishing the foundation for quantitative photometry [2] [4].

1760: Johann Heinrich Lambert formalized Bouguer's observations mathematically, expressing the exponential relationship between transmission and path length [2] [4].

1852: August Beer extended the law to incorporate concentration dependence, recognizing that absorbance in solutions relates directly to solute concentration [2] [4].

1913: Robert Luther and Andreas Nikolopulos provided the modern mathematical formulation emphasizing the logarithmic relationship between intensity and concentration/path length [2].

Mathematical Formulations

The Beer-Lambert Law establishes that absorbance is directly proportional to the concentration of the absorbing species and the path length through the medium. The fundamental equation is:

Where:

- A = Absorbance (unitless)

- ε = Molar absorptivity or extinction coefficient (M⁻¹cm⁻¹)

- c = Concentration (M)

- l = Path length (cm)

This relationship derives from the logarithmic dependence of absorbance on transmittance:

Where:

- I₀ = Incident light intensity

- I = Transmitted light intensity

Transmittance (T) is defined as T = I/I₀, with absorbance relating to transmittance as A = -log₁₀(T) [3] [5].

Table 2: Relationship Between Absorbance and Transmittance

| Absorbance (A) | Transmittance (T) | % Transmittance | Light Transmitted |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 100% | All light transmitted |

| 0.3 | 0.5 | 50% | Half of incident light |

| 1 | 0.1 | 10% | One-tenth of incident light |

| 2 | 0.01 | 1% | One-hundredth of incident light |

| 3 | 0.001 | 0.1% | One-thousandth of incident light |

Limitations and Practical Considerations

The linear relationship described by the Beer-Lambert Law holds true only under specific conditions [4] [5]:

- Monochromatic Light: The law assumes measurements with single-wavelength light.

- Low Concentrations: At high concentrations (typically A > 1), molecular interactions can cause deviations from linearity.

- Chemical Independence: Absorbing species must not interact chemically.

- No Scattering: The sample should not scatter significant radiation.

- Homogeneous Solutions: Samples must be uniformly distributed.

For reliable quantitative measurements, absorbance values between 0.1 and 1.0 are recommended, corresponding to 80-10% light transmission [5]. Measurements with absorbance greater than 3.0 may be subject to significant error due to insufficient light reaching the detector [5].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Quantitative Concentration Determination

Protocol 1: Standard Curve Method for Solution Concentration

Preparation of Standard Solutions: Create a series of standard solutions with known concentrations spanning the expected range of the unknown samples.

Spectrometer Setup: Allow the UV-Vis spectrometer to warm up for appropriate stabilization time (typically 30 minutes). Set the optimal wavelength based on the compound's absorption maximum (λmax).

Blank Measurement: Fill a cuvette with solvent alone and measure the baseline absorbance to zero the instrument.

Standard Measurement: Measure the absorbance of each standard solution using consistent instrument parameters (bandwidth, integration time) and path length (typically 1 cm).

Calibration Curve: Plot absorbance versus concentration for the standard solutions and perform linear regression analysis.

Unknown Sample Measurement: Measure the absorbance of the unknown sample under identical conditions and determine concentration from the calibration curve.

Data Analysis: The slope of the calibration curve equals ε·l, allowing determination of the molar absorptivity if path length is known [3].

Molar Absorptivity Determination

Protocol 2: Direct Measurement of Extinction Coefficient

Accurate Weighing: Precisely weigh a pure, dry sample of the compound of interest.

Solution Preparation: Dissolve in a suitable solvent to create a stock solution of known concentration.

Dilution Series: Prepare appropriate dilutions to ensure absorbance measurements fall within the linear range (0.1-1.0 AU).

Absorbance Measurement: Measure absorbance at the compound's λmax using a spectrophotometer with calibrated wavelength accuracy.

Calculation: Apply the Beer-Lambert Law rearranged as ε = A/(c·l), using the known concentration and path length.

Validation: Repeat with multiple concentrations to confirm consistency of the calculated ε values, indicating adherence to the Beer-Lambert Law.

Spectral Acquisition for Compound Identification

Protocol 3: Full Spectrum Analysis for Compound Characterization

Sample Preparation: Prepare a solution with appropriate concentration to yield absorbance values between 0.5-1.0 at the strongest absorption band.

Instrument Parameters: Set the spectrophotometer to scan across the UV-Vis range (typically 190-800 nm) with appropriate resolution (1-2 nm).

Data Collection: Record the full absorption spectrum, identifying all local maxima and minima.

Spectral Analysis: Note the wavelength of maximum absorption (λmax) and corresponding molar absorptivity (ε) for each peak, which serve as characteristic identifiers for the compound.

Advanced Applications and Modifications

Modified Beer-Lambert Law for Biological Tissues

In scattering media like biological tissues, the traditional Beer-Lambert Law requires modification to account for photon path lengthening due to scattering [4]. The Modified Beer-Lambert Law (MBLL) incorporates a Differential Pathlength Factor (DPF):

OD = -log(I/I₀) = DPF · μₐ · d + G [4]

Where:

- OD = Optical density

- DPF = Differential pathlength factor (typically 3-6 for biological tissues)

- μₐ = Absorption coefficient

- d = Inter-optode distance

- G = Geometry-dependent factor

This approach enables quantitative spectroscopy in highly scattering media such as living tissues, with applications in determining blood oxygen saturation and chromophore concentrations [4].

Multicomponent Analysis

For mixtures containing multiple absorbing species, the Beer-Lambert Law becomes:

A(λ) = l · Σ(εᵢ(λ) · cᵢ)

Where the total absorbance at each wavelength equals the sum of contributions from all chromophores. By measuring absorbance at multiple wavelengths and solving simultaneous equations, concentrations of individual components can be determined [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for UV-Vis Spectroscopy

| Item | Function/Specification | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Quartz Cuvettes | Path length typically 1 cm; transparent down to 190 nm | Required for UV measurements below 350 nm; handle by edges only |

| Methanol/UHPLC Grade | High-purity solvent with low UV absorbance | Suitable for background measurements; check purity at low wavelengths |

| Deuterium Lamp | UV light source (190-380 nm) | Standard in UV-Vis spectrometers; limited visible range output [6] |

| Tungsten Lamp | Visible light source (380-800 nm) | Often combined with D₂ lamp for full UV-Vis capability [6] |

| NIST-Traceable Standards | Reference materials for wavelength and absorbance calibration | Essential for method validation and regulatory compliance |

| Buffer Salts (e.g., PBS) | Maintain physiological pH for biological samples | Check UV transparency at desired wavelengths |

| Protein Assay Dyes | Bind proteins for enhanced detection (e.g., Bradford) | Enable protein quantification at visible wavelengths [5] |

| NADH/NAD+ Cofactors | Monitor enzyme kinetics at 340 nm | NADH absorbs at 340 nm while NAD+ does not [5] |

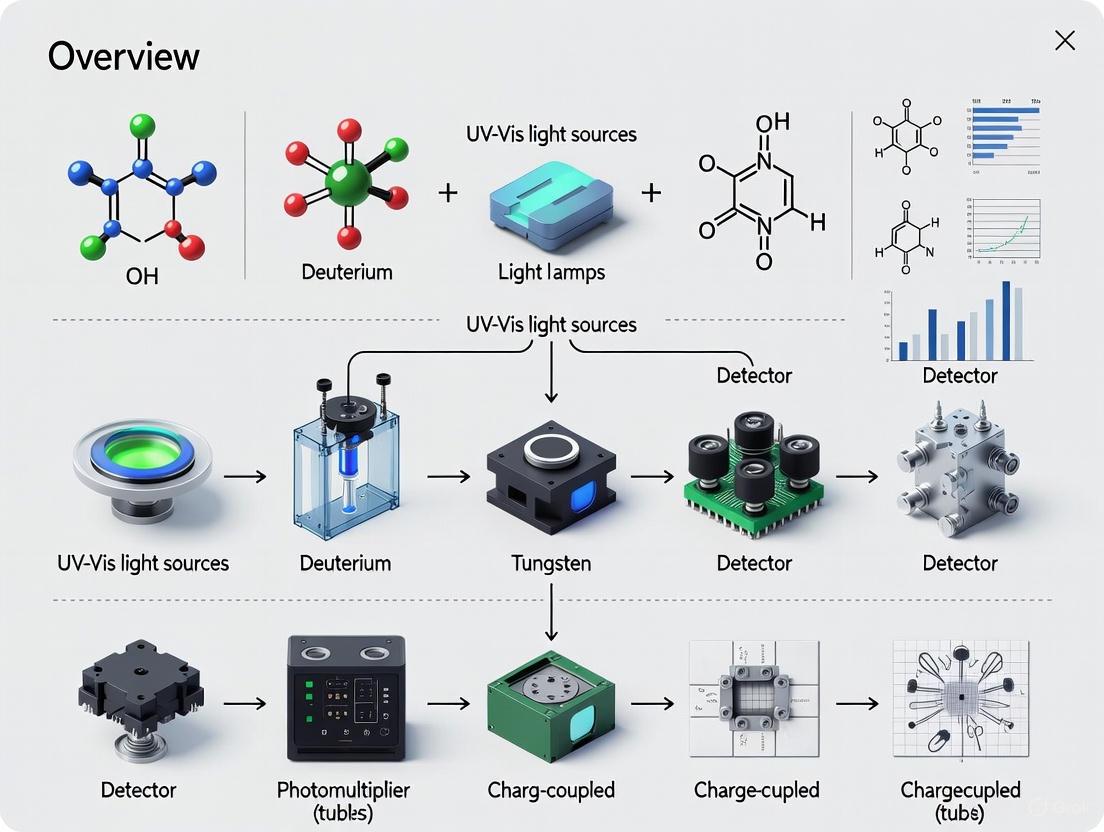

Visualization of Core Concepts

Electronic Transitions and Molecular Orbital Theory

UV-Vis Spectrometer Optical Configuration

Beer-Lambert Law Experimental Workflow

Contemporary Instrumentation and Technological Advances

Current UV-Vis Detector Technologies

Modern HPLC systems typically employ two primary types of UV-Vis detection systems:

Variable Wavelength Detectors (VWD): These instruments use a monochromator with movable diffraction grating to select specific wavelengths before the light passes through the flow cell. This design provides high sensitivity with minimal noise [7] [6].

Diode Array Detectors (DAD/PDA): These detectors pass broad-spectrum light through the flow cell, then disperse it onto an array of photodiodes (typically 512-1024 elements). This enables simultaneous capture of the entire spectrum, facilitating peak purity assessment and spectral comparison for compound identification [7] [6].

Recent market analyses indicate rapid growth in UV-Visible spectrometer technologies, with increasing integration of miniaturized and portable systems for field applications and automated workflow solutions for high-throughput laboratories [8]. The global UV-Visible spectrometers market is projected to grow from USD 1.5 billion in 2024 to USD 2.8 billion by 2033, at a compound annual growth rate of 7.5% [8].

Emerging Trends and Future Directions

The field of UV-Vis spectroscopy continues to evolve with several significant trends:

Integration of Artificial Intelligence: Machine learning algorithms are increasingly employed for spectral interpretation, calibration model development, and predictive maintenance of instrumentation [8].

Hybrid Spectrometer Systems: Combining UV-Vis with other analytical techniques provides comprehensive analytical solutions for complex sample matrices [9] [8].

Portable and Field-Deployable Instruments: Miniaturization technologies enable on-site analysis in environmental monitoring, pharmaceutical manufacturing, and food safety applications [8].

Enhanced Data Management Systems: Cloud-based platforms facilitate remote monitoring, data sharing, and collaborative research efforts across multiple sites [8].

Recent instrumentation reviews highlight novel products such as the Bruker Vertex NEO platform with vacuum FT-IR technology that removes atmospheric interference, and specialized systems like the ProteinMentor from Protein Dynamic Solutions designed specifically for protein analysis in biopharmaceutical applications [9].

The fundamental principles of electronic transitions and the Beer-Lambert Law remain cornerstones of modern analytical chemistry, providing the theoretical foundation for UV-Vis spectroscopy. While these core concepts have endured for centuries, their implementation continues to evolve through technological advancements in light sources, detector designs, and data analysis methodologies. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding these principles enables proper experimental design, accurate data interpretation, and informed selection of analytical instrumentation. As UV-Vis technology progresses toward greater automation, miniaturization, and intelligence, the integration of these fundamental principles with advanced instrumentation will continue to drive scientific discovery and innovation across pharmaceutical, biotechnology, and materials science domains.

Ultraviolet-Visible (UV-Vis) spectroscopy stands as a cornerstone analytical technique in modern laboratories, providing critical insights for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. This technology measures the absorption of ultraviolet and visible light by molecules, yielding essential information about their composition, structure, and concentration [10]. The reliability and accuracy of any UV-Vis spectroscopic analysis are fundamentally dependent on two core components: the light source, which generates the incident electromagnetic radiation, and the detector, which captures the resulting signal after sample interaction [10] [11]. Understanding the intricate roles, operating principles, and technological variations of these components is paramount for optimizing analytical methods, particularly in highly regulated sectors like pharmaceuticals where method validation and data integrity are crucial. This guide provides a detailed technical examination of UV-Vis light sources and detector technology, framing this discussion within the context of their application in advanced research and drug development environments.

Fundamental Principles of UV-Vis Spectroscopy

UV-Vis spectroscopy operates on the principle that molecules absorb light in the ultraviolet (typically 190-400 nm) and visible (400-800 nm) regions of the electromagnetic spectrum [12] [10]. When a molecule absorbs this energy, its electrons are promoted from a ground state to a higher energy excited state. The wavelength at which this absorption occurs and the intensity of the absorption provide a characteristic profile, or spectrum, that can be used for both qualitative identification and quantitative analysis [13].

The relationship between light absorption and sample concentration is quantitatively described by the Beer-Lambert Law, which states that absorbance (A) is directly proportional to the concentration (c) of the absorbing species, the path length (L) of the sample container, and the molar absorptivity (ε) of the species [10]. This relationship is expressed mathematically as:

A = ε × c × L

This fundamental equation forms the basis for most quantitative applications of UV-Vis spectroscopy, from determining active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) concentrations in drug formulations to monitoring reaction kinetics in chemical research. The technique's remarkable sensitivity allows for the detection of components at concentrations as low as 10⁻⁷ to 10⁻⁴ g/mL, with relative errors typically between 1% and 5%, making it indispensable for analytical applications where precision is critical [12].

The Light Source: Illuminating the Sample

Function and Operating Principles

The light source in a UV-Vis spectrophotometer serves the fundamental purpose of generating a stable and continuous beam of electromagnetic radiation across the entire ultraviolet and visible wavelength range. The quality of the source directly impacts the instrument's sensitivity, signal-to-noise ratio, and overall analytical performance. A perfect source would emit constant energy across all wavelengths, but in practice, all real light sources exhibit some wavelength-dependent intensity variations that must be accounted for during measurement and calibration [10].

The underlying physical principle governing light source operation is the inverse relationship between a photon's energy and its wavelength. Shorter wavelengths in the UV region carry more energy than longer wavelengths in the visible region [10]. This energy differential is significant because promoting electrons in different bonding environments within a molecule requires specific, quantized amounts of energy. Consequently, the light source must provide a broad, continuous spectrum to ensure that the appropriate wavelengths are available to interact with the electronic structure of the analyte molecules being examined [10].

No single lamp technology can optimally cover the entire UV-Vis spectral range with uniform intensity. Therefore, most modern UV-Vis spectrophotometers employ either a single broadband source or, more commonly, multiple specialized sources that are automatically switched or blended during operation to provide seamless coverage across the spectrum. The table below summarizes the key characteristics of the most prevalent light source technologies.

Table 1: Comparison of Common UV-Vis Spectrometer Light Sources

| Source Type | Spectral Range | Key Characteristics | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Deuterium Lamp [12] [10] | 165-360 nm (UV) | Intense continuum in UV region, lower output in visible; requires warm-up time for stability | Primary UV source in dual-lamp systems; pharmaceutical QC; nucleic acid analysis |

| Tungsten-Halogen Lamp [12] [10] | 360-2500 nm (Vis-NIR) | Stable, intense output across visible spectrum; relatively low cost; longer lifespan | Primary visible light source in dual-lamp systems; color measurement; quantitative colorimetric assays |

| Xenon Lamp [10] | 175-2000 nm (UV-Vis-NIR) | Continuous spectrum across UV-Vis; high intensity; no switching required; more expensive and less stable than tungsten/halogen | Single-lamp systems; fast scanning applications; fluorescence spectroscopy |

| LED [11] | Varies by diode (specific bands) | Long lifetime; low power consumption; instant on/off; limited to specific wavelength bands | Portable/handheld instruments; dedicated analyzers; process monitoring |

In instruments employing two lamps, the switch between the deuterium and tungsten-halogen sources typically occurs between 300 and 350 nm, a region where the light emission characteristics of both sources are sufficiently similar to allow for a smooth transition [10]. More advanced systems incorporate sophisticated optics and software algorithms to manage this transition seamlessly, ensuring consistent energy delivery throughout the entire spectral scan.

The Detector: Capturing the Signal

Function and Operating Principles

Following the interaction of light with the sample, the detector performs the critical function of converting the transmitted light energy into a measurable electronic signal. The detector's sensitivity, dynamic range, and response characteristics ultimately determine the instrument's ability to distinguish subtle absorbance differences and measure low-concentration analytes [10]. In essence, the detector quantifies the intensity of light that has passed through the sample (I), which is then compared to the intensity of the initial incident light (I₀) to calculate transmittance (T = I/I₀) and subsequently absorbance (A = log₁₀(I₀/I)) [10].

The performance of a detector is governed by several key parameters. Sensitivity refers to the detector's ability to respond to very low light levels, which is essential for detecting dilute samples or analytes with low molar absorptivity. Signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) determines the clarity of the signal against the background electronic and photonic noise, directly impacting detection limits and measurement precision. Dynamic range defines the span between the lowest and highest detectable light intensities, enabling the analysis of both concentrated and dilute samples without requiring dilution. Wavelength response specifies the range over which the detector maintains optimal sensitivity, which must align with the operational spectral range of the instrument [10] [11].

Types of Detectors

Detector technology has evolved significantly, with modern UV-Vis spectrophotometers employing various detection systems tailored to specific application requirements. The selection of an appropriate detector depends on factors such as the required sensitivity, scanning speed, spectral resolution, and cost considerations.

Table 2: Comparison of Common UV-Vis Spectrometer Detectors

| Detector Type | Operating Principle | Sensitivity & Speed | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Photomultiplier Tube (PMT) [12] [10] [11] | Photoelectric effect followed by electron multiplication through dynodes | Very high sensitivity; moderate scan speed (sequential wavelength measurement) | Research-grade instruments; low-light applications; high-resolution spectroscopy |

| Photodiode [10] [11] | Semiconductor-based; photon absorption creates electron-hole pairs generating current | Good sensitivity; faster than PMT | Routine analytical instruments; educational systems |

| Photodiode Array (PDA) [11] | Array of individual photodiodes; all wavelengths measured simultaneously | Good sensitivity; very fast acquisition (simultaneous measurement) | Rapid scans; kinetic studies; HPLC detectors |

| Charge-Coupled Device (CCD) [10] [11] | Semiconductor chip with pixels that accumulate charge proportional to light intensity | High sensitivity in array configuration; very fast acquisition | Advanced spectroscopic applications; imaging spectroscopy |

In process analytical technology (PAT) and industrial settings, detectors are particularly crucial as they enable continuous, real-time measurements without requiring manual sampling or process interruption. As noted in a ColVisTec 2024 report highlighted in a market analysis, modern detectors can perform measurements at intervals as frequent as every 10 seconds or less, providing near-instantaneous feedback for process control in pharmaceutical manufacturing and other industries [14].

Instrument Configuration and Workflow

Understanding how the source and detector function within the complete optical system is essential for appreciating their integrated roles. The following diagram illustrates the typical arrangement of components in a conventional UV-Vis spectrophotometer.

Diagram 1: UV-Vis Spectrometer Component Workflow

The optical pathway begins with the light source, which emits polychromatic (broad spectrum) radiation. This light then passes through a wavelength selection device, typically a monochromator containing a diffraction grating that disperses the light into its constituent wavelengths [10] [11]. By rotating the grating, specific narrow wavelength bands can be sequentially directed toward the sample. The monochromator's resolution, determined largely by the number of grooves per millimeter on the grating (typically 1200 grooves/mm or more for research-grade instruments), defines the instrument's ability to distinguish between closely spaced absorption peaks [10].

After passing through the sample compartment, where a portion of the light is absorbed by the analyte, the transmitted light reaches the detector. The detector converts the photon energy into an electrical signal, which is then amplified, processed, and converted to digital format for analysis and display [10] [11]. Modern instruments automatically compare this sample signal to a reference measurement (typically of the pure solvent or buffer) to compute the true absorbance of the analyte at each wavelength, ultimately generating the characteristic absorption spectrum.

Advanced Applications in Pharmaceutical Research and Development

The precise interplay between sophisticated light sources and sensitive detectors enables a wide range of advanced applications in pharmaceutical research and development. These components are particularly crucial for meeting the increasingly stringent quality control standards in pharmaceutical manufacturing, where real-time monitoring and precise quantification are mandatory [14].

In-line UV-Vis spectroscopy has emerged as a powerful process analytical technology (PAT) for the pharmaceutical industry, allowing for real-time monitoring of critical process parameters without the need for manual sampling or process interruption [14]. For instance, a 2020 innovation demonstrated the development and validation of an online UV-Vis spectroscopy method for quantitative analysis of active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) concentration during continuous manufacturing [14]. This application relies on robust light sources that maintain stable output in production environments and detectors capable of precise, rapid measurements at controlled intervals—some modern systems can perform measurements as frequently as every 10 seconds [14].

The detection of formaldehyde and its analogs represents another application showcasing the sensitivity of modern UV-Vis systems. A 2022 methodology published in the Journal of Hazardous Materials described using O-(carboxymethyl) hydroxylamine as a derivatization agent that reacts with formaldehyde to form an oxime bond with strong UV absorption at 197 nm [15]. The experimental protocol for this sensitive detection method is outlined below:

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Formaldehyde Detection via UV-Vis

| Reagent/Material | Specifications | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|---|

| O-(carboxymethyl) hydroxylamine | C₂H₅NO₃·0.5HCl, 1 mM in aqueous media | Derivatization agent; reacts specifically with aldehydes to form UV-absorbing oxime bonds |

| Formaldehyde standards | 1 μM to 0.2 mM in aqueous solution | Calibration and quantitative analysis; establishes linear range (1 μM to 0.2 mM) |

| Quartz cuvettes | 1 cm path length, high UV transparency | Sample holder; ensures minimal UV absorption by cell itself |

| UV-Vis Spectrophotometer | Equipped with deuterium lamp and photomultiplier tube (PMT) detection | Measurement system; provides high sensitivity in low UV range (197 nm) |

The methodology achieved an impressive detection limit of 0.03 ppm for formaldehyde, surpassing or comparable with many existing methods while offering advantages in simplicity, cost-effectiveness, and avoidance of secondary pollution [15]. This application exemplifies how advances in both source stability (particularly at lower UV wavelengths around 200 nm) and detector sensitivity enable the solution of challenging analytical problems with practical significance for environmental safety and public health.

Further expanding the utility of UV-Vis spectroscopy, recent innovations have integrated machine learning approaches with spectral analysis. A 2024 development introduced a molecular-feature-based machine learning model (ABOCH algorithm) that uses random forest regression to predict the UV-Vis absorption spectra of volatile compounds, achieving a prediction accuracy (R²) of 0.715 [14]. Such advancements demonstrate how the fundamental data generated by source-detector systems can be enhanced through computational approaches to provide even greater analytical insights.

Future Trends and Technological Advancements

The evolution of UV-Vis spectrometer components continues to drive the technique's capabilities and applications. Several emerging trends are particularly noteworthy for research scientists and drug development professionals.

Market analysis indicates sustained growth in the UV-Vis spectroscopy market, which was valued at approximately $1.6 billion in 2025 and is projected to reach $3.1 billion by 2035, growing at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 7% [14]. This growth is fueled by several factors, including the expanding patient population requiring continuous pharmaceutical treatments, increasingly stringent quality control requirements in pharmaceutical manufacturing, and substantial investments in research and development [14].

Detector technology continues to advance, with developments focused on higher sensitivity, faster response times, and improved signal-to-noise ratios. The pharmaceutical industry's adoption of Industry 4.0 principles is driving demand for detectors that can interface seamlessly with digital systems for real-time process monitoring and control [14]. These "smart detectors" are becoming integral components in automated quality assurance systems, capable of performing continuous measurements without manual intervention.

Similarly, light source technology is evolving, with LEDs becoming increasingly prevalent in specialized applications due to their long lifetimes, low power requirements, and instant-on capability [11]. While currently limited in spectral breadth compared to traditional broadband sources, advances in LED technology are expanding their usable range, particularly for portable and dedicated analyzer applications where specific wavelength regions are targeted.

The integration of UV-Vis spectroscopy with other analytical techniques represents another significant trend. A 2025 innovation demonstrated a high-temperature modular optical cell that combined UV-Vis spectroscopy with laser-induced breakdown spectroscopy (LIBS), enabling gas phase monitoring at temperatures up to 450°C [14]. Such hybrid approaches leverage the complementary strengths of different techniques while sharing common optical components, including sources and detectors.

These technological advancements, combined with growing regulatory acceptance and the technique's inherent versatility, ensure that UV-Vis spectroscopy will remain an essential tool in the researcher's arsenal, with source and detector technology continuing to be at the forefront of the technique's ongoing development.

In the realm of analytical instrumentation, particularly ultraviolet-visible (UV-Vis) spectroscopy and High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC), light sources are critical components that define the capabilities and limitations of the system. These technologies convert electrical energy into electromagnetic radiation, enabling scientists to probe the molecular composition of samples by analyzing how they absorb light. Among the most prevalent sources are deuterium, tungsten-halogen, and xenon lamps, each possessing unique spectral characteristics and operational principles. The selection of an appropriate lamp is a strategic decision that directly influences the sensitivity, accuracy, and scope of analytical methods in fields ranging from pharmaceutical quality control to academic research.

This guide provides an in-depth examination of these three core light source technologies. Understanding their distinct emission profiles, inherent stability, lifetime considerations, and application-specific advantages is fundamental for researchers and drug development professionals who rely on precise and reliable spectroscopic data. This knowledge forms the foundation of a broader overview of UV-Vis and detector technology, ensuring that the illumination source is optimally matched to the analytical task.

Fundamental Principles of UV-Vis Spectroscopy

Ultraviolet-visible (UV-Vis) spectroscopy is a cornerstone analytical technique that measures the amount of discrete wavelengths of UV or visible light absorbed by or transmitted through a sample. The fundamental principle hinges on the interaction between light and matter: molecules can absorb light energy, promoting their electrons to higher energy states. The specific amount of energy required for this transition is characteristic of the molecular structure, leading to absorption at particular wavelengths. This provides a fingerprint for identifying substances and, via the Beer-Lambert Law, quantifying their concentration in a solution [10].

A UV-Vis spectrophotometer operates by guiding light from a source through a wavelength selector, through the sample, and onto a detector. The light source must provide a steady emission across a wide range of wavelengths. Instruments often employ a combination of lamps—such as a deuterium lamp for UV and a tungsten-halogen lamp for visible light—to cover the entire spectrum from approximately 190 nm to 1100 nm. The wavelength selector, typically a monochromator containing a diffraction grating with a groove frequency of 1200 grooves per mm or higher, isolates specific wavelengths for sample examination. After passing through the sample, the light is captured by a detector, such as a photomultiplier tube (PMT) or a photodiode, which converts the light intensity into an electronic signal for analysis [10]. The following diagram illustrates the core workflow of a UV-Vis spectrophotometer.

Deuterium Lamps (D₂ Lamps)

Deuterium lamps are a type of arc discharge lamp specifically engineered to provide a continuous and stable spectrum in the ultraviolet region. The lamp is filled with deuterium gas, and light is generated by creating an electric arc through the ionized gas. Unlike a typical light bulb, the filament (a heated cathode) is primarily used to initiate and maintain the arc discharge, which is the true source of illumination. This process emits light directionally from one side of the lamp [16]. Deuterium lamps are renowned for their high stability and low fluctuation, with some models achieving peak-to-peak noise levels as low as 0.005% [17].

The primary application of deuterium lamps is in UV-Vis spectrophotometry and HPLC-UV detection for absorption measurements in the UV range. Their stable output in this critical region makes them indispensable for high-precision analytical work. Key operational considerations include a required warm-up time to ensure a reliable arc and the need for a stable, complex power supply to maintain constant current [16]. The average operational lifespan of a deuterium lamp is approximately 2000 hours, but this can be significantly reduced by frequent ignition or continuous operation. Best practices involve turning the lamp off during extended idle periods but avoiding repeatedly switching it on and off in short intervals [16].

Tungsten-Halogen Lamps

Tungsten-halogen lamps are advanced incandescent sources that produce light by heating a tungsten filament to extremely high temperatures. Their key differentiator is the halogen regenerative cycle. Within a quartz envelope filled with an inert gas and a small amount of a halogen (e.g., hydrogen bromide), evaporated tungsten from the filament reacts with the halogen to form a gaseous compound. Thermal convection currents carry this compound back to the hot filament, where it dissociates and re-deposits tungsten. This cycle prevents the tungsten from blackening the envelope and allows the filament to operate at higher temperatures, resulting in a brighter light and a longer, more stable operational life compared to standard incandescent lamps [18].

These lamps are characterized by a continuous spectral output that spans the visible and near-infrared regions, with the majority of emitted energy being in the infrared as heat. They are the illumination source of choice for visible light measurements in spectroscopy and are also widely used in microscopy [16] [18]. A typical tungsten-halogen lamp for spectroscopy has a wavelength range of 320–1100 nm to 360–2700 nm, depending on the model [16] [19]. The average lifespan is around 1000 hours [19]. The following diagram illustrates the critical halogen regenerative cycle that defines this technology.

Xenon Lamps

Xenon lamps are high-intensity arc lamps that generate light by passing an electric current between two electrodes in a xenon gas-filled quartz envelope. These lamps produce a broad, continuous spectrum that covers the ultraviolet, visible, and infrared regions, effectively mimicking sunlight. A key characteristic of their output is the presence of sharp, high-intensity spectral lines superimposed on the continuous background, particularly in the 850–900 nm region [17] [20]. Xenon lamps have a high color temperature, typically around 5800 K, which contributes to their sun-like quality [20].

Due to their high intensity and broad spectrum, xenon lamps are suited for demanding applications such as fluorescence, absorbance spectral scanning, and solar simulation [21] [17]. A significant consideration is their output fluctuation, which can be around 1% peak-to-peak, making them less stable than deuterium lamps for precise UV measurements [17]. Furthermore, the intense UV emission below 242 nm can produce toxic ozone, requiring ventilation or the use of specially coated "ozone-free" lamps if deep UV is not needed [21]. The average lifespan of a 150 W xenon short-arc lamp is about 2000 hours [20].

Comparative Technical Analysis

Spectral Range and Performance

The core distinction between deuterium, tungsten-halogen, and xenon lamps lies in their spectral emission profiles, which directly dictate their application domains. The following table provides a structured comparison of their key quantitative and operational characteristics for easy reference.

Table 1: Comparative Technical Specifications of Deuterium, Tungsten-Halogen, and Xenon Lamps

| Parameter | Deuterium Lamp | Tungsten-Halogen Lamp | Xenon Arc Lamp |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wavelength Range | 165–400 nm (stable: 190–370 nm) [16] [17] | 320–1100 nm to 360–3800 nm [16] [19] | 185–2000 nm (typical: 240–2400 nm) [17] [20] |

| Spectrum Covered | Ultraviolet (UV) [16] | Visible (VIS) & Near-Infrared (NIR) [16] [18] | UV, VIS, & Infrared (IR) [17] |

| Output Stability (Peak-Peak) | ~0.005% [17] | ~0.05% (with stabilization) [19] | ~1% [17] |

| Average Lifespan | ~2000 hours [16] | ~1000 hours [19] | 750–2000 hours [21] [20] |

| Key Strengths | Excellent UV stability, continuous UV spectrum [16] [17] | Continuous VIS-NIR spectrum, cost-effective, robust [16] [18] | High-intensity, broad spectrum, sun-like [21] [17] |

| Common Applications | UV spectroscopy, HPLC, AAS [16] [17] | VIS spectroscopy, microscopy, routine QC [16] [18] | Fluorescence, solar simulation, wafer inspection [21] [17] |

Selection Guidelines for Specific Applications

Choosing the correct light source is paramount for method performance. The following guidelines aid in this selection:

- For Exclusive UV Absorption Measurements: A deuterium lamp is the preferred choice due to its superior stability and continuous output in the 190–370 nm range, which is critical for precise absorbance measurements in HPLC and UV spectroscopy [16].

- For Visible & NIR Absorption Measurements: A tungsten-halogen lamp is ideal. Its strong, continuous output across the visible and into the near-infrared makes it perfect for colorimetric analysis and routine quality control where UV stability is not a concern [16] [10].

- For Full-Spectrum Scanning & Demanding Applications: A xenon lamp is suitable when a single, high-intensity source is needed to cover a very broad range from UV to IR, such as in fluorescence spectroscopy or rapid scanning spectrophotometers [10] [17].

- Combined UV-Vis Systems: Many spectrophotometers use both a deuterium and a tungsten-halogen lamp together. This combination covers the entire UV-Vis range (e.g., ~190–1100 nm) by leveraging the strengths of each source, with an automated switchover typically occurring around 300–350 nm [16] [10].

The schematic below provides a logical workflow for selecting the most appropriate lamp technology based on primary application requirements.

Implementation in HPLC and Drug Development

In High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC), detectors function as the "eyes" of the system, and the light source is a fundamental component of optical detectors. The strategic choice of detector and its corresponding lamp directly impacts the sensitivity, selectivity, and regulatory compliance of analytical methods in pharmaceutical development [22].

UV-Vis and PDA Detectors are the most commonly used in pharmaceutical laboratories. These detectors measure the absorption of light by compounds as they elute from the chromatographic column. The concentration of the analyte is quantified based on the amount of light absorbed, following the Beer-Lambert Law [16] [22]. Within these detectors, the combination of deuterium and tungsten-halogen lamps enables the coverage of both UV and visible wavelengths, allowing for the analysis of a wide array of compounds with different chromophores [16]. The Photodiode Array (PDA) detector, which captures absorbance data across multiple wavelengths simultaneously, particularly benefits from a stable, broadband light source for advanced applications like peak purity assessment and impurity profiling [22].

Table 2: HPLC Detector Technologies and Light Source Implications

| Detector Type | Sensitivity | Selectivity | Role of Light Source | Typical Use Case in Pharma |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UV-Vis [22] | Moderate | Moderate | Provides specific wavelength for absorption measurement; D2 & Tungsten combo covers UV-Vis. | Routine quality control of active ingredients. |

| PDA [22] | Moderate | High | Provides broad spectrum for simultaneous multi-wavelength capture; enables spectral fingerprinting. | Method development, impurity analysis. |

| Fluorescence [22] | High | Very High | Provides high-intensity excitation wavelength (often xenon lamp). | Bioanalysis, trace-level impurity detection. |

| Refractive Index (RID) [22] | Low | Low | Does not use a light source for absorption. Universal detector. | Analysis of sugars, polymers, non-UV absorbing compounds. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details key materials and reagents essential for working with and maintaining these light source technologies in a research setting.

Table 3: Essential Materials and Reagents for Light Source Operation and Maintenance

| Item | Function/Description | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Quartz Cuvettes [10] | Sample holders transparent to UV light (down to ~190 nm). Standard path length is 1 cm. | UV Spectroscopy: Essential for accurate UV absorption measurements, as glass and plastic absorb UV light. |

| UV Protective Eyewear [21] | Safety goggles designed to block ultraviolet radiation. | General Safety: Mandatory when operating UV-emitting lamps (Deuterium, Xenon) to protect eyes from damage. |

| Lint-Free Cloths & Alcohol [19] [20] | For cleaning optical components without scratching or leaving residue. | Lamp Maintenance: Critical for cleaning lamp envelopes. Dust and grease can cause hot spots and lamp failure. |

| Powder-Free Gloves [19] [20] | To handle lamps without depositing skin oils on the quartz envelope. | Lamp Handling: Prevents contamination during installation/replacement of all lamp types. |

| Stable Power Supply [16] | Provides constant current and voltage to the lamp for stable output. | System Operation: Especially critical for deuterium and xenon arc lamps to maintain arc discharge and spectral stability. |

| Liquid Light Guide [19] [20] | A flexible guide that transports light from the source to the sample using a liquid core. | Light Delivery: Useful for directing high-power light (e.g., from tungsten-halogen or xenon sources) to remote samples. |

Emerging Trends and Innovations

The field of light source technology continues to evolve, with trends focusing on increasing stability, longevity, and integration with data systems. Key developments include:

- Advanced Halogen Mixtures: Research into new fill gas and halogen mixtures for tungsten-halogen lamps aims to further improve life span and shift emission profiles for greater visible light output [18].

- Intelligent Systems: The integration of AI and machine learning for spectroscopic data interpretation is becoming more prevalent, supporting faster impurity profiling and predictive quality control, which relies on stable, high-quality light source data [22].

- Automation and Data Integrity: Stronger connections between HPLC systems and Laboratory Information Management Systems (LIMS) drive automation and ensure audit-ready data, making the consistent performance of light sources even more critical [22].

Deuterium, tungsten-halogen, and xenon lamps are foundational technologies in modern analytical science, each occupying a distinct and critical niche. Deuterium lamps offer unmatched stability in the ultraviolet region, tungsten-halogen lamps provide reliable and cost-effective coverage of the visible and near-infrared spectrum, and xenon lamps deliver high-intensity, broad-spectrum illumination for specialized applications. The strategic selection of a light source, based on a thorough understanding of its spectral output, stability, and operational requirements, is a decisive factor in developing robust, sensitive, and compliant analytical methods for drug development and quality control. As detection technologies advance, the synergistic use of these traditional light sources with new computational tools will continue to empower scientists in the pursuit of precise and reliable chemical analysis.

In the realm of ultraviolet-visible (UV-Vis) spectroscopy, the detector plays a pivotal role, serving as the critical component that converts a light signal into a quantifiable electrical output. The evolution from photomultiplier tubes (PMTs) to photodiode arrays (PDAs) represents a significant technological shift, each offering distinct advantages tailored to the demanding needs of modern laboratories. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, the choice of detector directly impacts key performance metrics, including sensitivity, speed, and the ability to deconvolute complex samples. This guide provides an in-depth technical examination of these core detector technologies, framing them within the broader context of UV-Vis light sources and detection systems to inform instrument selection and methodological design.

The fundamental principle underlying all UV-Vis detectors is the conversion of light energy into an electrical current. When photons strike the detector's active material, they transfer their energy, liberating electrons and generating a measurable signal proportional to the light's intensity [10]. This signal, after processing, produces the absorbance or transmittance spectra used for qualitative and quantitative analysis. The specific mechanism of this conversion and the subsequent amplification of the signal are where PMT and PDA technologies fundamentally diverge, leading to their unique performance characteristics and ideal application spaces.

Photomultiplier Tube (PMT) Technology

Operating Principle and Structure

The photomultiplier tube is a highly sensitive vacuum tube detector that excels in measuring low-intensity light. Its operation is based on a combination of the photoelectric effect and secondary emission [23]. The process begins when incident photons strike a photocathode material, which is typically a thin, vapor-deposited conducting layer on the inside of the device's entry window. Upon absorbing a photon, the photocathode ejects a primary electron via the photoelectric effect [10] [23].

These primary electrons are then focused and accelerated by an electric field towards a series of electrodes known as dynodes. Each dynode is held at a successively more positive potential (approximately 100 volts higher than the last). When a primary electron strikes the first dynode, its kinetic energy causes the emission of several secondary electrons. This electron cascade is repeated at each subsequent dynode, resulting in a geometric multiplication of the signal. A typical PMT with 10-12 dynode stages can achieve amplification factors as high as 100 million (10⁸), enabling the detection of single photons [23]. The final, greatly multiplied swarm of electrons is collected at the anode, producing a sharp, easily measurable current pulse.

Key Performance Characteristics

The unique design of the PMT grants it several notable performance characteristics:

- Extremely High Sensitivity and Low Noise: The multi-stage amplification process allows PMTs to detect extremely low light levels, making them ideal for applications like low-light-level spectroscopy and fluorescence spectroscopy [23].

- Fast Response Time: PMTs have ultra-fast response characteristics, making them suitable for time-resolved measurements and high-frequency applications [23].

- Large Area of Collection: This feature, combined with high gain, makes PMTs essential in applications requiring the detection of imperfectly collimated light [23].

However, PMTs are also susceptible to damage if exposed to high-intensity light and generally require high operating voltages (on the order of 1000 V) [24] [23].

Photodiode Array (PDA) Technology

Operating Principle and Structure

The photodiode array detector represents a solid-state approach to light detection. A PDA is a multichannel detector consisting of a linear array of hundreds to thousands of individual light-sensing silicon photodiodes—typically ranging from 128 to 1024, and even up to 4096—fabricated on a single silicon chip [25] [24]. Each diode acts as an independent detector for a specific wavelength.

A key differentiator of PDA-based spectrophotometers is their reverse optics design. In this configuration, polychromatic (white) light first passes through the sample. The transmitted light is then dispersed into its constituent wavelengths by a fixed diffraction grating before being projected simultaneously onto the entire photodiode array [25] [26]. Each diode measures the intensity of a specific, narrow band of wavelengths concurrently. This allows the entire spectrum to be captured in under one second, as there is no need for a mechanical scanning mechanism to cycle through wavelengths [27].

Key Performance Characteristics

The solid-state, multi-channel design of PDAs confers distinct advantages:

- Simultaneous Multi-Wavelength Acquisition: The ability to measure all wavelengths at once drastically reduces analysis time and is ideal for monitoring reaction kinetics and capturing transient intermediates [26].

- High Ruggedness and Reliability: With no moving parts, PDAs are less prone to misalignment and mechanical wear. This makes them robust and lowers maintenance requirements, allowing them to be moved between laboratories without recalibration [27] [26].

- Minimal Stray Light and Wavelength Precision: The reverse optics design minimizes stray light. Furthermore, because data is acquired at all wavelengths simultaneously without moving the grating, there is high wavelength precision and repeatability [26].

- Dynamic Range and Speed: While traditionally less sensitive than PMTs, PDAs offer sufficient sensitivity for a wide range of applications and provide unparalleled speed for capturing full spectra [27].

Comparative Analysis: PMT vs. PDA Detectors

The choice between a PMT and a PDA detector is application-dependent. The table below summarizes their core technical differences to guide this decision.

Table 1: Technical Comparison of PMT and PDA Detectors

| Feature | Photomultiplier Tube (PMT) | Photodiode Array (PDA) |

|---|---|---|

| Basic Principle | Photoelectric effect & secondary emission [23] | Semiconductor photon absorption [24] |

| Optical Design | Scanning (sample after monochromator) | Reverse optics (sample before polychromator) [26] |

| Sensitivity | Extremely high (single-photon detection) [23] | High, but generally lower than PMT [24] |

| Signal-to-Noise | Very high, due to internal gain | Good; can be improved by time-averaging [26] |

| Spectral Acquisition | Sequential (one wavelength at a time) | Simultaneous (all wavelengths at once) [26] |

| Acquisition Speed | Slower (limited by mechanical scanning) | Very fast (full spectrum in <1 second) [27] |

| Ruggedness | Moderate (vacuum tube, sensitive to overload) | High (solid-state, no moving parts) [27] [26] |

| Stray Light | More susceptible | Minimal due to reverse optics [26] |

| Key Advantage | Superior sensitivity for low-light applications | Speed and simultaneous wavelength detection |

Visualizing the Optical Pathways

The fundamental difference in how these detectors acquire a spectrum is best understood through their instrument geometries. The following diagrams illustrate the distinct optical paths of conventional PMT-based and PDA-based spectrophotometers.

Experimental Protocols and Applications

The selection of a detector is ultimately dictated by the requirements of the experimental protocol. The following section details methodologies where the choice of detector is critical to success, particularly in a pharmaceutical development context.

Protocol 1: Dissolution Testing of Solid Dosage Forms (PDA Application)

Dissolution testing is a critical quality control (QC) procedure for solid oral dosage forms (e.g., tablets, capsules) to ensure the drug dissolves appropriately [27].

- Objective: To measure the rate and extent of active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) release from a solid dosage form under standardized conditions.

- Detector Rationale: In high-volume QC laboratories, a single PDA instrument can analyze samples from multiple dissolution vessels rapidly. The speed of capturing the full UV-Vis spectrum simultaneously allows for efficient testing of a large number of samples without sacrificing data quality [27].

- Methodology:

- Apparatus Setup: Use a USP-compliant dissolution apparatus (basket or paddle type) filled with a suitable dissolution medium (e.g., buffer at pH 1.2-6.8) maintained at 37±0.5°C.

- Sample Introduction: Place the tablet or capsule into the vessel and start the apparatus at a specified rotational speed (e.g., 50-75 rpm).

- Automated Sampling: At predetermined time points (e.g., 10, 20, 30, 45, 60 minutes), an autosampler withdraws an aliquot from each vessel and transfers it to the flow-through cell of the PDA spectrophotometer.

- Spectral Acquisition: The PDA captures the full UV-Vis spectrum (e.g., 190-400 nm) of each sample in under a second. This allows for the verification of the API's identity based on its spectral profile and the quantification of its concentration using Beer-Lambert's law at the wavelength of maximum absorbance (λmax) [27] [10].

- Data Analysis: Software calculates the cumulative percentage of API dissolved at each time point, generating a dissolution profile for comparison with regulatory specifications.

Protocol 2: High-Sensitivity Quantification of Nucleic Acids (PMT Application)

Accurately quantifying low-concentration nucleic acid samples (DNA/RNA) is essential in molecular biology and biopharmaceutical research.

- Objective: To determine the concentration and purity of nucleic acid samples with high accuracy, especially when sample volume is limited.

- Detector Rationale: The extreme sensitivity of the PMT makes it ideal for measuring the low signal from highly diluted or micro-volume samples, a common scenario in nucleic acid work [27] [10].

- Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Dilute the nucleic acid sample in the same buffer as the blank (e.g., TE buffer or nuclease-free water). For micro-volume systems, 1-2 µL of sample is directly pipetted onto the measurement surface [28].

- Blank Measurement: The instrument first measures the blank to establish a baseline.

- Spectrum Scanning: The PMT-based spectrophotometer sequentially scans across a wavelength range, typically 220-350 nm. The high gain of the PMT allows for precise measurement of the weak absorbance signals.

- Concentration & Purity Calculation:

- DNA Concentration: Calculated from the absorbance at 260 nm (A₂₆₀), where one A₂₆₀ unit corresponds to 50 µg/mL for double-stranded DNA.

- Purity Assessment: The ratios A₂₆₀/A₂₈₀ and A₂₆₀/A₂₃₀ are calculated. Pure DNA typically has an A₂₆₀/A₂₈₀ ratio of ~1.8 and an A₂₆₀/A₂₃₀ ratio >2.0. Deviations indicate contamination from protein or chaotropic salts, respectively [10].

Protocol 3: HPLC-Peak Purity and Deconvolution Analysis (PDA Application)

In High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC), a PDA detector provides an additional dimension of information beyond simple retention time, which is crucial for method development and impurity profiling in drug analysis [29].

- Objective: To confirm the identity of a chromatographic peak and assess its purity by verifying the homogeneity of its UV-Vis spectrum across the peak.

- Detector Rationale: The PDA's ability to collect the full spectrum in real-time for every data point in the chromatogram is indispensable. It enables spectral comparison for identity confirmation and software-based deconvolution of co-eluting peaks [29].

- Methodology:

- Chromatographic Separation: The sample mixture is separated using a suitable HPLC column and mobile phase gradient.

- On-the-Fly Spectral Acquisition: As each compound elutes from the column and passes through the HPLC-PDA flow cell, the detector captures its full UV-Vis spectrum (e.g., 190-800 nm) at a high frequency (e.g., 10-50 points per second).

- Peak Purity Analysis:

- The software compares the spectra from the upslope, apex, and downslope of the chromatographic peak.

- A peak purity index is generated. A high similarity between all spectra indicates a pure peak, while spectral differences suggest a co-eluting impurity [29].

- Peak Deconvolution (i-PDeA):

- For partially resolved or co-eluting peaks, the different spectral profiles of the components are used by advanced algorithms (e.g., Shimadzu's i-PDeA) to mathematically resolve the overlapping peaks.

- The technique relies on the fact that each compound has a unique absorbance spectrum, which serves as a fingerprint for deconvolution and individual quantification [29].

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Featured Protocols

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) | Dissolution medium; provides physiological ionic strength and pH for dissolution testing. | Dissolution Testing (5.1) |

| TE Buffer (Tris-EDTA) | Protects nucleic acids from degradation; standard diluent for accurate UV quantitation. | Nucleic Acid Quantification (5.2) |

| HPLC-Grade Solvents (e.g., Acetonitrile, Water) | Mobile phase components; high purity is critical to minimize baseline noise and ghost peaks. | HPLC-Peak Purity (5.3) |

| Nucleic Acid (DNA/RNA) Standard | Calibrant for verifying instrument response and accuracy of quantification measurements. | Nucleic Acid Quantification (5.2) |

| Certified Reference Material (CRM) | Pure API standard for constructing a calibration curve in dissolution method validation. | Dissolution Testing (5.1) |

The landscape of UV-Vis detection is characterized by two powerful technologies: the photomultiplier tube and the photodiode array. The PMT remains the undisputed champion for applications demanding the ultimate in sensitivity, such as detecting single photons or analyzing extremely dilute and micro-volume samples. Conversely, the PDA offers transformative advantages in speed, ruggedness, and simultaneous multi-wavelength data acquisition, making it a workhorse for high-throughput QC, kinetic studies, and hyphenated techniques like HPLC.

For the drug development professional, this choice is not merely technical but strategic. The trend is moving towards the integration of these technologies with artificial intelligence for enhanced data processing and the proliferation of miniaturized, portable systems for on-site analysis [8]. Understanding the core principles, strengths, and limitations of PMT and PDA detectors, as outlined in this guide, empowers scientists to make informed decisions that optimize analytical workflows, ensure data integrity, and ultimately accelerate the path from research to therapeutic product.

Ultraviolet-Visible (UV-Vis) spectrophotometry is a cornerstone analytical technique in scientific research and industrial laboratories, enabling the quantitative and qualitative analysis of substances by measuring their absorption of light. The core principle involves passing a beam of light through a sample and detecting the intensity of the transmitted light to determine absorbance, which relates to the sample's concentration and molecular structure [10]. Within this domain, the instrument's internal optical design—specifically, whether it is based on a single-beam or a double-beam configuration—is a critical determinant of its analytical performance, particularly concerning stability and accuracy [30]. This guide provides an in-depth technical comparison of these two designs, framing the discussion within the broader context of UV-Vis light source and detector technology. It is tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals who require a detailed understanding of these instruments to make informed decisions that ensure data integrity in critical applications such as pharmaceutical quality control and biochemical research [30] [9].

Fundamental Operational Principles

Single-Beam Spectrophotometer Design and Workflow

A single-beam spectrophotometer operates on a fundamentally simple optical principle: a single beam of light travels along one path from the source to the detector. The light source, which can be a tungsten, halogen, or xenon lamp, emits broadband light [10] [30]. This light is then passed through a monochromator, a key component typically based on a diffraction grating, which selects a specific, narrow wavelength band to illuminate the sample [10] [31]. The quasi-monochromatic light passes through the sample contained in a cuvette, and a detector, such as a photomultiplier tube (PMT) or photodiode, measures the intensity of the transmitted light [10].

The operational workflow for obtaining an absorbance measurement is sequential. First, the instrument must be zeroed or calibrated using a blank solution (typically the pure solvent) placed in the cuvette. This measures the reference intensity ((I0)). The blank is then manually replaced with the sample solution, and the intensity after passing through the sample ((I)) is measured. The absorbance (A) is calculated using the formula (A = \log{10}(I_0/I)) [30] [32]. This design's simplicity is its primary advantage, but the necessity for manual switching between reference and sample makes the measurement susceptible to fluctuations in the light source intensity and electronic drift between the two sequential measurements [30] [31].

Dual-Beam Spectrophotometer Design and Workflow

The dual-beam spectrophotometer addresses the inherent stability challenges of the single-beam design by incorporating a mechanism to simultaneously measure the sample and reference. In this configuration, the light beam exiting the monochromator is split into two separate, identical beams: the sample beam and the reference beam [30] [33].

This beam splitting is commonly achieved using a beam splitter or a rotating chopper that alternately directs light through the two paths at a high frequency [30] [31]. One beam passes through the sample cuvette, while the other passes through a reference cuvette containing the blank solvent. The two beams are then recombined and directed onto a single detector, or they are measured by two matched detectors. The instrument's microprocessor continuously calculates the ratio of the two intensities ((I{sample}) and (I{reference})), providing a real-time absorbance value (A = \log{10}(I{reference}/I_{sample})) [30] [31]. This ratiometric measurement is the key to the dual-beam instrument's enhanced stability, as any fluctuation in the light source intensity or detector sensitivity affects both beams equally and is therefore canceled out in the calculated absorbance ratio [30] [33].

The following diagram illustrates the core optical pathways and components of both systems, highlighting the key difference in their approaches to measurement.

Performance Comparison: Stability, Accuracy, and Application Suitability

The fundamental architectural differences between single-beam and dual-beam spectrophotometers lead directly to divergent performance characteristics in stability, accuracy, and suitability for specific laboratory applications. The following table provides a structured, quantitative comparison of these critical parameters.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Single-Beam vs. Dual-Beam Spectrophotometer Performance

| Performance Parameter | Single-Beam Spectrophotometer | Dual-Beam Spectrophotometer |

|---|---|---|

| Optical Path Design | Single light path through monochromator, sample, and detector [30]. | Single beam split into reference and sample beams; measured simultaneously [30]. |

| Measurement Principle | Sequential measurement of blank ((I0)) and sample ((I)); (A = \log{10}(I_0/I)) [30] [32]. | Simultaneous ratiometric measurement; (A = \log{10}(I{reference}/I_{sample})) [30]. |

| Compensation for Source Fluctuations | No; intensity fluctuations directly impact measured absorbance, adding noise [30]. | Yes; self-compensating. Intensity changes affect both beams equally, canceling out [30] [31]. |

| Baseline Stability | Subject to drift due to environment and instrument aging, affecting accuracy over time [30]. | High; baseline drift affects both beams proportionately, minimizing its influence [30] [33]. |

| Typical Analytical Accuracy | Limited, especially at high/low absorbance where noise and drift have greater impact [30]. | Superior; accuracy remains relatively constant across a wider absorbance range [30] [33]. |

| Typical Precision | Lower due to uncompensated baseline drift and source noise [30]. | Significantly higher due to reduced drift and ratiometric measurement [30]. |

| Dynamic Range | Limited, can lead to truncated spectra at high/low absorbance [30]. | Wider, allowing accurate analysis of samples with very high or low absorbance [30]. |

| Cost and Complexity | Simpler design, lower initial cost [30] [34]. | More complex design, typically more expensive [30]. |

| Ideal Application Scope | Routine quantitative analyses in stable environments, educational settings, high-throughput screening where cost and simplicity are key [30] [34]. | Research, method development, quality control, kinetic studies, and applications demanding high accuracy and precision [30] [33]. |

Analysis of Stability and Accuracy

The data in Table 1 underscores that the core advantage of the dual-beam design lies in its robust compensation for instrumental instabilities. In a single-beam instrument, any drift in the light source intensity (e.g., due to power fluctuations or lamp warming) or in the detector's response between the blank and sample measurements is misinterpreted as a change in sample absorbance, directly impacting accuracy and precision [30] [31]. This is particularly problematic for long-term studies or when measuring samples with very high or low absorbance, where the signal-to-noise ratio is already challenging [30].

The dual-beam instrument's ability to perform a simultaneous comparison renders it largely immune to these short-term fluctuations. This ratiometric approach provides inherent stability, leading to more reliable and reproducible data, which is non-negotiable in regulated environments like pharmaceutical quality control labs [30] [33]. Furthermore, the continuous baseline monitoring in a dual-beam system allows for more effective correction of background drift over time, ensuring higher photometric accuracy across a wider dynamic range [30].

Essential Methodologies and the Scientist's Toolkit

Experimental Protocol for Instrument Qualification and Verification

To ensure the accuracy of any UV-Vis spectrophotometer, regular performance verification is essential. The following protocol outlines key experiments for qualifying a dual-beam instrument, which can be adapted for single-beam use with additional care to account for drift.

Experiment 1: Wavelength Accuracy Verification

- Objective: To verify that the instrument's wavelength calibration is correct.

- Methodology:

- Use a holmium oxide or didymium glass filter, which has sharp, well-defined absorption peaks at known wavelengths [33].

- Place the filter in the sample compartment and acquire an absorbance spectrum over the appropriate range (e.g., 240-650 nm for holmium oxide).

- Record the wavelength values of the observed absorption peaks.

- Data Analysis: Compare the measured peak wavelengths to the certified values provided with the filter. The deviation should be within the manufacturer's specification (typically ±0.5 nm or better for a research-grade instrument) [33].

Experiment 2: Photometric Accuracy Verification

- Objective: To confirm the accuracy of the absorbance readings.

- Methodology:

- Prepare a solution of potassium dichromate (K₂Cr₂O₇) in dilute sulfuric acid (e.g., 0.001 M) or use a certified neutral density filter [33].

- For the solution, measure the absorbance at specific wavelengths (e.g., 235, 257, 313, and 350 nm) using a matched pair of high-quality quartz cuvettes.

- Ensure the absorbance values are within the linear range of the detector (preferably below 1.0 AU) [10].

- Data Analysis: Compare the measured absorbance values against the known standard values. The tolerance for photometric accuracy is typically within ±0.001 A or as specified by the manufacturer [33].

Experiment 3: Stray Light Detection

- Objective: To determine the level of stray light, which is light of unintended wavelengths reaching the detector and causing inaccurate absorbance readings, particularly at high absorbance.

- Methodology:

- Use a solution that completely absorbs light below a certain wavelength. A common standard for UV stray light is a concentrated potassium chloride (KCl) solution (e.g., 12 g/100 mL) [33].

- Measure the transmittance of this solution at a wavelength where it should be entirely opaque, such as 200 nm.

- Data Analysis: The measured transmittance at 200 nm is reported as the percent stray light. A value below 0.1% T is generally acceptable for a well-maintained instrument. High stray light can lead to a non-linear response at high absorbances and falsely low readings [33].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential consumables and reagents required for the operation, calibration, and maintenance of UV-Vis spectrophotometers.

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Materials for UV-Vis Spectrophotometry

| Item | Function and Application |

|---|---|

| High-Purity Solvents (HPLC Grade) | Used for sample preparation and as blank references. High purity is critical to avoid absorption interferences in the UV range [33]. |

| Matched Quartz Cuvettes | Standard sample holders for UV-Vis analysis. Quartz is transparent down to ~190 nm. Must be "matched" to ensure identical path lengths for accurate quantitative work, especially in dual-beam systems [10] [33]. |

| Holmium Oxide Filter | A solid-state wavelength accuracy standard with sharp absorption peaks. Used for routine verification of the instrument's wavelength calibration [33]. |

| Potassium Dichromate Solution | A primary standard for verifying photometric (absorbance) accuracy. Requires careful preparation and dilution [33]. |

| Potassium Chloride Solution | Used for assessing stray light levels in the UV region, a critical parameter for ensuring accuracy at high absorbance values [33]. |

| Cuvette Cleaning Solutions | Specialized, residue-free solutions (e.g., Hellmanex III) or solvents for cleaning cuvettes to prevent contamination and scratching, which can scatter light and affect results [32]. |

Future Trends: The Impact of Light Source and Detector Technology

The ongoing evolution of UV-Vis spectrophotometry is heavily influenced by advancements in its core components: light sources and detectors. A significant trend is the move toward light-emitting diodes (LEDs) as alternative light sources. UV-LEDs offer advantages such as compact size, high energy efficiency, instant on/off capability, tunable wavelength, and exceptional operational lifetime [35] [36]. Furthermore, global environmental policy, specifically the Minamata Convention on Mercury, is driving the phase-out of traditional mercury lamps, accelerating the adoption of these mercury-free, solid-state light sources [35].

These developments are blurring the traditional single/double-beam paradigm. The stability and long life of LEDs can mitigate one of the key weaknesses of single-beam designs—source fluctuation. This has led to the proliferation of robust, portable, and cost-effective LED-based spectrophotometers suitable for field and point-of-use analysis [36]. Concurrently, improvements in detector technology, such as the use of charge-coupled devices (CCDs), enable non-scanning instruments that capture entire spectra simultaneously [10] [31]. When combined with advanced optical designs, these detectors facilitate new instrument architectures that can offer performance previously associated only with traditional dual-beam systems, but in smaller, more automated, and more connected formats suitable for the modern laboratory [9].

The choice between a single-beam and dual-beam UV-Vis spectrophotometer is a fundamental decision that directly impacts the quality and reliability of analytical data. The single-beam design, with its simplicity and lower cost, is a capable tool for routine, high-throughput, or educational applications where the highest level of stability is not required. In contrast, the dual-beam design, through its ratiometric measurement principle, provides superior stability, accuracy, and precision, making it the instrument of choice for demanding research, method development, and quality control in regulated industries.