Validating Machine Learning Models for Reaction Optimization: From Foundational Concepts to Clinical Impact

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the validation of machine learning (ML) models for optimizing chemical and biochemical reactions.

Validating Machine Learning Models for Reaction Optimization: From Foundational Concepts to Clinical Impact

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the validation of machine learning (ML) models for optimizing chemical and biochemical reactions. It explores the foundational need for ML in navigating complex reaction spaces, details specific methodologies like Bayesian Optimization and ensemble models, and addresses critical troubleshooting aspects such as data scarcity and algorithm selection. A core focus is placed on robust validation frameworks, including interpretability techniques like SHAP and comparative performance analysis, to ensure model reliability and build trust for their application in accelerating biomedical research and pharmaceutical synthesis.

The Critical Role of Machine Learning in Modern Reaction Optimization

The exploration of chemical reaction space is a fundamental challenge in modern chemistry. With an estimated 10^60 possible compounds in chemical compound space alone, the corresponding space of possible reactions that connect them is vaster still [1]. Traditional, intuition-driven methods are fundamentally inadequate for navigating this high-dimensional complexity. As this guide will demonstrate through comparative data and experimental protocols, machine learning (ML) provides a non-empirical, data-driven framework to rationally explore, reduce, and optimize these immense spaces, dramatically accelerating research and development timelines.

The Experimental Landscape of Reaction Optimization

Before the advent of ML, chemists relied on labor-intensive methods to explore reactions. The table below compares these traditional approaches with modern ML-driven workflows.

| Feature | Traditional / Human-Driven | ML-Driven Optimization |

|---|---|---|

| Experimental Design | One-factor-at-a-time (OFAT); grid-based fractional factorial plates [2] | Bayesian optimization; quasi-random Sobol sampling [2] |

| Search Space Navigation | Relies on chemical intuition and prior experience [1] | Data-driven; balances exploration of new conditions with exploitation of known successes [2] |

| Parallelism | Limited by manual effort and design complexity | Highly parallel; efficiently handles batch sizes of 96 reactions or more [2] |

| Key Outcome | Risk of overlooking optimal regions; slow timelines [2] | Identifies high-performing conditions in a minimal number of experimental cycles [2] |

| Application Example | Manual design of Suzuki reaction conditions | Minerva framework autonomously optimized a Ni-catalyzed Suzuki reaction, finding conditions with 76% yield and 92% selectivity where traditional HTE plates failed [2]. |

A critical step in applying ML is obtaining a meaningful numerical representation of chemical reactions. Common methods include:

- Reaction Difference Fingerprints: This representation subtracts the molecular fingerprint of the products from the fingerprint of the reagents, creating a vector that quantifies the "essence" of the chemical transformation itself [3]. Topological torsion descriptors have been shown to perform well for this purpose [3].

- BERT-based Fingerprints (BERT FP): Adapted from natural language processing, these models treat reaction SMILES strings as text to generate vector representations in a fully data-driven way [3].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure reproducibility and provide a clear basis for comparison, here are the detailed methodologies for two key ML applications in reaction space.

Protocol 1: ML-Powered Reduction of a Reaction Network for Methane Combustion

This protocol is based on a first-principles study that used ML to extract a reduced reaction network from a vast space of possibilities [1].

- Database Creation (Rad-6): A database of 10,712 closed- and open-shell molecules containing C, O, and H (up to 6 non-hydrogen atoms) was constructed using a graph-based approach. Ground-state geometries and energies were determined using DFT (PBE0 functional with Tkatchenko-Scheffler dispersion corrections) [1].

- Reaction Energy Calculation: The energy of a reaction (A → B + C) was calculated from the atomization energies (Eat) of the molecules involved: Ereac = Eat^B + Eat^C - E_at^A [1].

- Machine Learning Model:

- Algorithm: Kernel Ridge Regression (KRR).

- Molecular Representation: Smooth Overlap of Atomic Positions (SOAP), which describes the local chemical environment around each atom [1].

- Kernel Choice: An intensive kernel (average kernel) was used to learn the atomization energy per atom, which was then multiplied by the number of atoms to recover the total energy. This approach accounts for the special topology of reaction spaces where central "hub" molecules participate in many reactions [1].

- Network Reduction: The learned reaction energies were used to rationally prune the vast network of all possible reactions, selecting a thermodynamically feasible sub-network for detailed microkinetic analysis of methane combustion [1].

Protocol 2: Highly-Parallel Multi-Objective Reaction Optimization with Minerva

This protocol outlines the workflow for the ML-guided optimization of a nickel-catalyzed Suzuki reaction [2].

- Define Search Space: A combinatorial set of ~88,000 plausible reaction conditions is defined, including categorical variables (ligands, solvents, additives) and continuous variables (temperature, concentration). The space is automatically filtered to exclude impractical or unsafe combinations [2].

- Initial Sampling: The first batch of 96 experiments is selected using Sobol sampling, a quasi-random method designed to maximize the diversity and coverage of the initial search [2].

- ML Model and Multi-Objective Acquisition:

- Regressor: A Gaussian Process (GP) regressor is trained on the collected experimental data to predict reaction outcomes (e.g., yield, selectivity) and their uncertainties for all remaining conditions [2].

- Acquisition Function: A scalable multi-objective function like q-NParEgo, Thompson sampling with hypervolume improvement (TS-HVI), or q-NEHVI is used to select the next batch of experiments. These functions balance exploring uncertain regions of the search space with exploiting known high-performing conditions, while efficiently handling multiple competing objectives (e.g., maximizing yield and selectivity) [2].

- Iterative Loop: Steps 3 and 4 are repeated. After each batch, the GP model is updated with new data, and the acquisition function proposes the next most informative batch of experiments. The campaign terminates when performance converges or the experimental budget is exhausted [2].

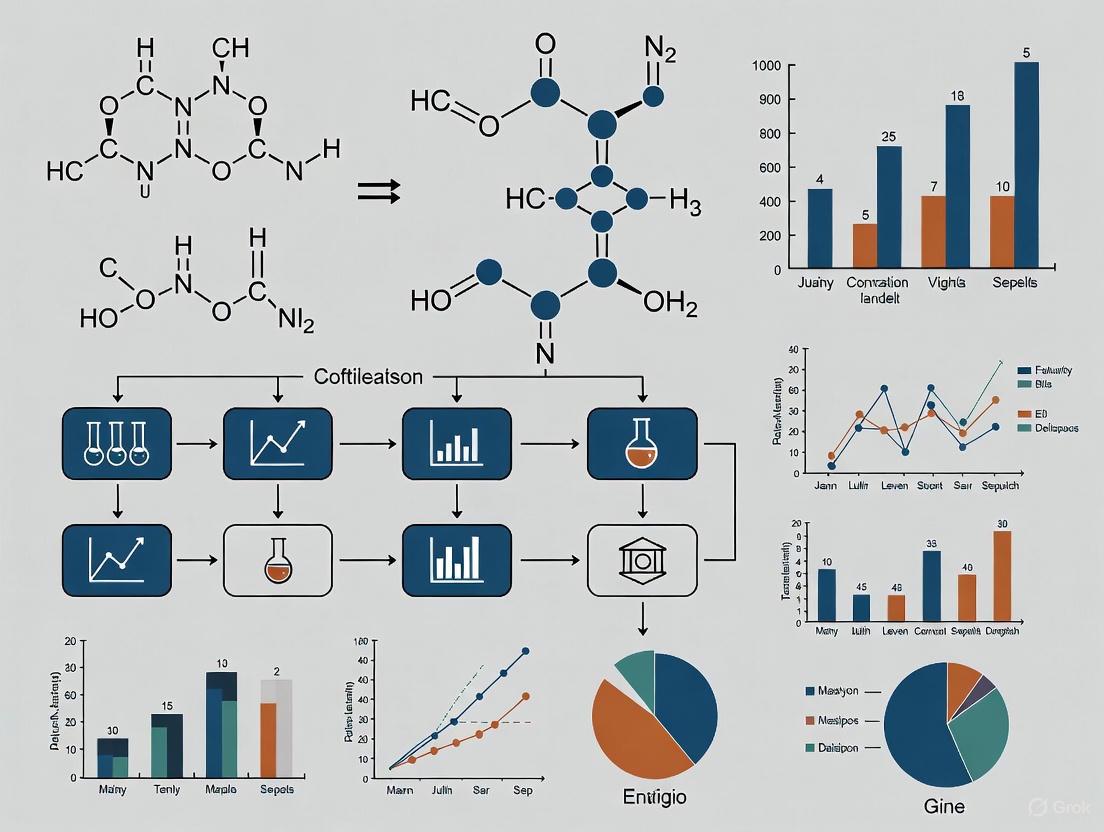

The following diagram illustrates the core optimization loop described in Protocol 2.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The table below catalogs key resources and computational tools essential for implementing the ML-driven reaction optimization workflows described in this guide.

| Tool/Resource | Function & Explanation |

|---|---|

| High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) | Automated platforms that use miniaturized reaction scales and robotics to execute highly parallel experiments (e.g., 96 reactions at once), generating the large datasets needed for ML [2]. |

| Smooth Overlap of Atomic Positions (SOAP) | A powerful mathematical representation that converts the 3D atomic structure of a molecule into a fixed-length vector, capturing its chemical environment for use in ML models [1]. |

| Gaussian Process (GP) Regressor | A core ML algorithm that predicts reaction outcomes and, crucially, quantifies the uncertainty of its own predictions. This uncertainty is the key to guiding exploratory experiments [2]. |

| Acquisition Function (e.g., q-NParEgo) | The decision-making engine in Bayesian optimization. It uses the GP's predictions and uncertainties to score all possible experiments and select the most promising batch [2]. |

| Reaction Fingerprints (e.g., Difference FP) | Numerical representations of chemical reactions that enable computational analysis and visualization of the reaction space, allowing algorithms to "see" and compare different reactions [3]. |

| Parametric t-SNE | A dimensionality reduction technique that projects high-dimensional reaction fingerprints onto a 2D plane, allowing researchers to visually explore reaction space and identify clusters of similar reaction types [3]. |

The experimental data and protocols presented here validate that machine learning is not merely an incremental improvement but a paradigm shift for navigating complex chemical spaces. ML-driven workflows consistently outperform traditional methods by replacing intuition with efficient, data-driven search strategies. Frameworks like Minerva demonstrate robust performance against real-world challenges, including high-dimensionality, experimental noise, and multiple objectives [2]. By adopting these tools, researchers and drug development professionals can systematically explore vast reaction territories, accelerate process development from months to weeks, and uncover optimal pathways that would otherwise remain hidden.

In the demanding fields of chemical synthesis and pharmaceutical development, optimizing reactions is a fundamental yet resource-intensive process. For decades, the one-factor-at-a-time (OFAT) approach has been a standard experimental method, where researchers isolate and vary a single parameter while holding all others constant. Rooted in intuitive, systematic reasoning, this method aims to clarify the individual effect of each variable. However, within the modern research context—which emphasizes efficiency, comprehensive understanding, and the validation of sophisticated machine learning models—the limitations of OFAT have become profoundly evident. This analysis objectively compares the performance of the traditional OFAT methodology against modern, data-driven machine learning (ML) techniques, using supporting experimental data to demonstrate their relative capabilities in reaction optimization.

OFAT vs. Modern Methods: A Fundamental Comparison

The one-factor-at-a-time (OFAT) method involves testing factors or causes individually rather than simultaneously [4]. While intuitive and straightforward to implement, this approach carries significant disadvantages, including an increased number of experimental runs for the same precision, an inability to estimate interactions between factors, and a high risk of missing optimal settings [4] [5].

In contrast, designed experiments, such as factorial designs, and Machine Learning (ML)-guided optimization represent more advanced paradigms. Factorial designs assess multiple factors at once in a structured setting, uncovering both individual effects and critical interactions [6]. ML-driven strategies, including Bayesian optimization, leverage algorithms to efficiently navigate vast, complex reaction spaces by learning patterns from data, balancing the exploration of unknown regions with the exploitation of promising conditions [7] [2].

The core limitations and advantages of these methodologies are summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Core Methodological Comparison: OFAT vs. Factorial Design vs. ML-Guided Optimization

| Feature | OFAT | Factorial Design | ML-Guided Optimization |

|---|---|---|---|

| Basic Principle | Changes one variable while holding others constant [4] | Tests all possible combinations of factors simultaneously [6] | Uses data-driven algorithms to suggest promising experimental conditions [7] |

| Experimental Efficiency | Low; requires many runs [6] | High; fewer runs than OFAT for multiple factors [6] | Very High; actively learns to minimize experimental effort [2] [8] |

| Interaction Detection | Cannot estimate interactions between factors [4] | Explicitly designed to detect and estimate interactions [6] | Can model complex, non-linear interactions from data [9] |

| Risk of Sub-Optimal Solution | High; can be trapped in a local optimum [5] | Lower; explores a broader solution space | Low; designed to escape local optima via exploration |

| Dependence on Experiment Order | High; final outcome can depend on which factor is optimized first [5] | Low; randomized run order prevents bias [6] | Algorithm-driven; order is part of the optimization strategy |

| Best Application Context | Initial learning about a new, simple system [5] | Controlled experiments with a moderate number of factors [6] | High-dimensional, complex spaces with multiple objectives [10] [2] |

Quantitative Performance Benchmarks

The theoretical drawbacks of OFAT manifest concretely as inferior performance in real-world optimization campaigns. Recent studies directly comparing these methods provide compelling quantitative evidence.

Table 2: Experimental Performance Benchmarks

| Study Focus / System | OFAT Performance & Effort | ML-Guided Performance & Effort | Key Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nickel-Catalyzed Suzuki Reaction [2] | Two chemist-designed HTE plates failed to find successful conditions. | Identified conditions with 76% yield and 92% selectivity in a 96-well campaign. | ML succeeded where traditional intuition-driven OFAT/HTE failed. |

| Pharmaceutical Process Development [2] | A prior development campaign took 6 months. | ML identified conditions with >95% yield/selectivity and improved scale-up conditions in 4 weeks. | ML accelerated process development timelines dramatically. |

| Enzymatic Reaction Optimization [8] | Traditional methods are "labor-intensive and time-consuming." | A self-driving lab using Bayesian optimization achieved rapid optimization in a 5-dimensional parameter space with minimal human intervention. | ML enabled fully autonomous, efficient optimization of complex bioprocesses. |

| Syngas-to-Olefin Conversion [10] | Achieving higher carbon efficiency "requires extensive resources and time." | A data-driven ML framework successfully predicted novel oxide-zeolite composite catalysts and optimal reaction conditions. | ML accelerated the discovery and optimization of novel catalytic systems. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To understand how these results are achieved, it is essential to examine the underlying experimental workflows.

Protocol for Traditional OFAT Optimization

The OFAT protocol is sequential and linear [5].

- Establish a Base Operating Point: Begin with a set of initial reaction conditions (e.g., catalyst, solvent, temperature, concentration) believed to be feasible.

- Select and Vary a Single Factor: Choose one variable (e.g., temperature) and define a range of values to test, keeping all other parameters constant at their base values.

- Execute and Analyze Experimental Series: Run reactions across the chosen variable's range. Measure the outcome (e.g., yield).

- Identify the Apparent Optimal Level: Select the variable level that produced the best outcome.

- Iterate to the Next Factor: Fix the first variable at its new "optimal" level, select a second variable (e.g., solvent), and repeat steps 2-4. This process continues until all factors have been tested.

This workflow's flaw is illustrated by a bioreactor example [5]: optimizing temperature first might suggest a lower temperature is best. Subsequently optimizing feed concentration at this low temperature leads to a suboptimal global solution, entirely missing the high-yield region that exists at a combination of high temperature and high concentration.

Protocol for ML-Guided Bayesian Optimization

ML-guided optimization, particularly using Bayesian Optimization (BO), follows an iterative, closed-loop cycle [2] [8].

- Define Search Space: A chemist defines a discrete combinatorial set of plausible reaction conditions, including categorical (e.g., ligand, solvent) and continuous (e.g., temperature, concentration) parameters, with practical constraints automatically enforced.

- Initial Quasi-Random Sampling: An initial batch of experiments is selected using an algorithm like Sobol sampling to diversify coverage of the reaction condition space [2].

- Model Training: A machine learning model (commonly a Gaussian Process regressor) is trained on the accumulated experimental data to predict reaction outcomes (e.g., yield, selectivity) and their associated uncertainties for all possible conditions in the search space [2].

- Acquisition Function & Batch Selection: An acquisition function uses the model's predictions and uncertainties to balance exploration (trying uncertain conditions) and exploitation (trying conditions predicted to be high-performing). This function selects the next most promising batch of experiments [2].

- Automated Experimentation & Loop Closure: The selected experiments are conducted, often via automated high-throughput experimentation (HTE). The new results are added to the dataset, and the loop (steps 3-5) repeats for a predetermined number of iterations or until performance converges.

Diagram 1: ML-Guided Bayesian Optimization Workflow

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key components and materials central to the experimental case studies cited, highlighting their function in advanced optimization campaigns.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions in Catalytic Reaction Optimization

| Reagent / Material | Function in Optimization | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Transition Metal Catalysts (Ni, Pd) | Central to catalyzing bond-forming reactions (e.g., cross-couplings); the choice of metal and its complex is a critical categorical variable. | Used in Ni-catalyzed Suzuki and Pd-catalyzed Buchwald-Hartwig reactions [2]. |

| Ligands | Modulate the steric and electronic properties of the metal catalyst; profoundly impact activity and selectivity. A key variable for ML screening. | A wide range of ligands are typically included in the search space for ML optimization [9] [2]. |

| Zeolites & Mixed Oxides | Bifunctional catalysts for complex transformations like syngas-to-olefin conversion; their composition and acidity are prime optimization targets. | OXZEO catalysts were optimized via an ML framework [10]. |

| Solvents | The reaction medium can influence solubility, stability, and reaction mechanism; a major categorical factor. | Solvent type is a common dimension in both HTE and ML screening plates [2]. |

| Enzymes | Biocatalysts offering high selectivity; their activity is optimized against parameters like pH and temperature. | A self-driving lab optimized enzymatic reaction conditions using Bayesian optimization [8]. |

The experimental data and comparative analysis presented lead to a definitive conclusion: the traditional one-factor-at-a-time method is fundamentally inadequate for navigating the high-dimensional, interactive landscapes of modern reaction optimization in research and development. Its inability to detect factor interactions and its propensity to converge on suboptimal solutions incur unacceptable costs in time, resources, and opportunity.

The validation of machine learning models for this purpose is not merely an academic exercise but a practical necessity. Frameworks like Bayesian Optimization integrated with high-throughput experimentation have demonstrated their superiority by consistently outperforming traditional methods, successfully tackling challenging reactions where intuition fails, and dramatically accelerating development timelines. For researchers and drug development professionals, the transition from OFAT to data-driven, ML-guided experimentation is no longer a question of if, but how swiftly it can be adopted to maintain a competitive edge.

In modern reaction optimization, particularly within pharmaceutical and complex organic synthesis, machine learning (ML) has transitioned from a novel assistive tool to a core component of the research workflow. This paradigm shift is driven by the need to navigate vast chemical spaces and multi-dimensional condition parameters efficiently, moving beyond traditional, resource-intensive trial-and-error approaches [11] [12]. The optimization of reactions, such as the ubiquitous amide couplings which constitute nearly forty percent of synthetic transformations in medicinal chemistry, presents a significant challenge due to the subtle interplay between substrate identity, coupling agents, solvents, and other reaction parameters [11]. This guide deconstructs the machine-learning-driven optimization pipeline into three foundational tasks: reaction outcome prediction, optimal condition search, and model-driven experimental validation. By objectively comparing the performance of models and algorithms designed for these tasks, this analysis provides a framework for researchers to select and validate appropriate computational strategies for their specific reaction optimization challenges.

Machine Learning Task 1: Reaction Outcome Prediction

Task Definition & Objective

The task of reaction outcome prediction involves training machine learning models to forecast the result of a chemical reaction—most commonly the yield—given a defined set of input parameters, including the reactants, catalyst, solvent, and other conditions [11] [13]. The objective is to build a surrogate model that accurately maps the complex relationship between reaction components and the outcome, thereby enabling virtual screening of potential conditions and providing a foundation for further optimization algorithms.

Performance Comparison of Predictive Models

Experimental data from a study evaluating 13 different ML architectures on diverse amide coupling reactions reveals significant performance variations. The models were trained on standardized data from the Open Reaction Database (ORD) to predict reaction yield (regression) and optimal coupling agent category (classification) [11].

Table 1: Performance of ML Models in Reaction Outcome Prediction [11]

| Model Architecture | Type | Primary Task | Key Finding / Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kernel Methods | Supervised | Classification | Significantly better performance for coupling agent classification |

| Ensemble Architectures | Supervised | Classification & Regression | Competitive accuracy in classification tasks |

| Linear Models | Supervised | Regression & Classification | Lower performance compared to kernel and ensemble methods |

| Single Decision Tree | Supervised | Classification | Lower performance compared to ensemble tree methods |

| Graph Neural Network (GNN) | Supervised | Yield Prediction | Competitive performance in yield prediction when pre-trained on large datasets [13] |

| Conditional VAE (CatDRX) | Supervised | Yield Prediction | RMSE of 9.8-13.1, MAE of 7.5-10.2 on various catalytic reaction datasets [13] |

Experimental Protocol for Predictive Modeling

The methodology for building such predictive models, as detailed in the amide coupling study, involves a multi-step process [11]:

- Data Acquisition and Curation: Source raw reaction data from public databases like the Open Reaction Database (ORD).

- Data Standardization and Filtering: Apply cheminformatics tools to standardize molecular representations (e.g., SMILES) and filter out inconsistent or erroneous entries.

- Feature Engineering: Compute molecular descriptors for all reaction components. The study found that molecular environment features (3D coordinates, Morgan Fingerprints of reactive groups) significantly boosted model predictivity compared to bulk material properties (molecular weight, LogP) [11].

- Model Training and Validation: Train multiple ML architectures (e.g., Linear, Tree-based, Neural Networks) on the processed dataset. Performance is evaluated using metrics like accuracy for classification and Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) for regression, validated on a hold-out test set or via cross-validation.

Figure 1: Workflow for building an ML model for reaction outcome prediction, highlighting the critical feature engineering step.

Machine Learning Task 2: Optimal Condition Search

Task Definition & Objective

This task focuses on actively searching the high-dimensional space of possible reaction conditions (e.g., catalyst, solvent, base, temperature) to identify the combination that maximizes a target objective, such as reaction yield [12] [14]. Unlike prediction, which models a fixed dataset, search is an iterative, active process that guides experimentation.

Performance Comparison of Search Algorithms

Benchmarking studies, particularly those using high-throughput experimentation (HTE) datasets for reactions like Suzuki-Miyaura and Buchwald-Hartwig couplings, provide quantitative comparisons of search efficiency. Performance is often measured by the Number of Trials (NT) required to find conditions yielding within the top X% of the possible search space [12].

Table 2: Performance of Algorithms for Optimal Condition Search [12]

| Search Algorithm | Type | Key Finding / Performance |

|---|---|---|

| Hybrid Dynamic Optimization (HDO) | Bayesian + GNN | 8.0% faster than top algorithms and 8.7% faster than 50 human experts in finding high-yield conditions; required 4.7 trials on avg. to beat expert suggestions [12]. |

| Bayesian Optimization (BO) | Sequential Model-Based | Strong performance, but requires ~10 initial random experiments, facing a "cold-start" problem [12]. |

| Random Forest (RF) | Ensemble / Surrogate | Used as a surrogate model in BO; requires numerous evaluations [12]. |

| Gaussian Processes (GP) | Surrogate Model | A classic surrogate for BO, but can be less suited for very high-dimensional or complex chemical spaces [12]. |

| Template-based (Reacon) | Supervised + Clustering | Top-3 accuracy of 63.48% for recalling recorded conditions; 85.65% top-3 accuracy within predicted condition clusters [14]. |

Experimental Protocol for Condition Search

The protocol for the benchmarked HDO algorithm illustrates a modern hybrid approach [12]:

- Define Search Space: Enumerate all possible combinations of pre-defined reaction components (catalysts, ligands, solvents, bases, etc.).

- Pre-train a Graph Neural Network: Train a GNN on a large, general reaction dataset (e.g., >1 million reactions) to learn the initial relationship between reaction components and outcomes.

- Iterative Bayesian Optimization: a. Surrogate Model: Use the pre-trained GNN (or another model like GP or RF) to predict the yield of all untested conditions in the search space. b. Acquisition Function: Propose the next experiment by selecting the condition that maximizes an acquisition function (e.g., Expected Improvement), which balances exploration and exploitation. c. Experimental Feedback: Conduct the proposed experiment, obtain the yield, and add this new data point to the training set. d. Model Update: Update the surrogate model with the new data and repeat until a satisfactory yield is achieved or the budget is exhausted.

Figure 2: The iterative workflow of a hybrid search algorithm like HDO, combining a pre-trained model with Bayesian optimization.

Machine Learning Task 3: Model Validation & Experimental Confirmation

Task Definition & Objective

Validation in ML-driven optimization extends beyond standard train-test splits. It encompasses the process of confirming that a model's predictions are reliable, generalizable, and ultimately useful for guiding real-world experimental synthesis. This includes validating both the model's computational predictions and the novel chemical entities or protocols it proposes [11] [13].

Performance Comparison of Validation Strategies

There is no single metric for validation; rather, a combination of computational checks and experimental confirmation is used to establish trust in the ML framework.

Table 3: Strategies for Validating ML Models in Reaction Optimization

| Validation Strategy | Type | Purpose / Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Train-Test Split on ORD Data | Computational | Standard ML validation; assesses baseline predictive performance on held-out data [11]. |

| External Validation on Literature Data | Computational | Tests model generalizability on data not present in the original training database [11]. |

| Ablation Studies | Computational | Isolates the contribution of specific model components (e.g., pre-training, data augmentation) to overall performance [13]. |

| Prospective Experimental Validation | Experimental | The ultimate test; synthesizing proposed catalysts or executing suggested conditions and measuring outcomes [13]. |

| Computational Chemistry Validation | Computational | Using Density Functional Theory (DFT) to validate the feasibility and mechanism of ML-generated catalysts [13]. |

Experimental Protocol for Model Validation

A robust validation protocol, as demonstrated in the CatDRX framework for catalyst design, involves multiple stages [13]:

- Standard Computational Assessment: Perform k-fold cross-validation or a strict train-test-validation split on the benchmark dataset, reporting metrics like RMSE, MAE, and R² for regression tasks.

- Ablation Studies: Systematically remove key components of the ML pipeline (e.g., pre-training, specific feature sets) to quantify their importance to the model's success.

- Prospective Experimental Validation: a. Candidate Generation: Use the trained model (e.g., a generative VAE) to propose novel, high-performing catalysts or conditions. b. Knowledge Filtering: Apply chemical knowledge filters (e.g., synthetic accessibility, stability rules) to screen generated candidates. c. Experimental Testing: Synthesize the top-ranked candidates and test them in the target reaction under standard conditions. d. Benchmarking: Compare the performance of the ML-proposed candidates against known catalysts or conditions from the literature.

- Mechanistic Validation: Employ computational chemistry methods, such as DFT calculations, to analyze the reaction pathway and transition states involving the ML-proposed catalyst, providing theoretical support for its efficacy [13].

Essential Research Reagents & Materials

The experiments cited in this guide rely on a suite of chemical reagents, computational tools, and data resources.

Table 4: Key Research Reagents and Resources for ML-Driven Reaction Optimization

| Reagent / Resource | Function / Purpose | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Kinetin (KIN) | Plant cytokinin used as a preconditioning agent in tissue culture studies [15]. | Optimizing in vitro regeneration in cotton [15]. |

| Murashige & Skoog (MS) Medium | Basal salt mixture for plant tissue culture [15]. | Serving as postconditioning medium in biological optimization [15]. |

| Open Reaction Database (ORD) | Source of open, machine-readable chemical reaction data [11]. | Training and benchmarking general-purpose predictive models [11] [13]. |

| USPTO Patent Dataset | Large dataset of reactions extracted from U.S. patents [14]. | Training template-based condition prediction models (Reacon) [14]. |

| Reaxys | Commercial database of chemistry information [12]. | Used in prior studies for training data-driven condition recommendation models [12]. |

| RDKit | Open-source cheminformatics toolkit [14]. | Molecule manipulation, descriptor calculation, and reaction template extraction [14]. |

| High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) | Technology for rapid, automated testing of numerous reaction conditions [12]. | Generating comprehensive benchmark datasets for optimizing and validating search algorithms [12]. |

In the field of machine learning (ML) for chemical synthesis, the scarcity of high-quality, diverse reaction data represents a fundamental bottleneck. The development of predictive ML models is critically limited by the lack of available, well-curated data sets, which often suffer from sparse distributions and a bias towards high-yielding reactions reported in the literature [16]. This data scarcity impedes the ability of models to generalize and identify optimal reaction conditions, particularly for challenging transformations like cross-couplings using non-precious metals. This guide objectively compares the performance of emerging data-centric ML strategies and experimental frameworks designed to overcome this challenge, providing researchers with a clear comparison of their capabilities, experimental requirements, and validation outcomes.

Comparative Analysis of Data-Centric ML Frameworks

The following section provides a detailed, data-driven comparison of two prominent approaches: one focused on enhancing learning from sparse historical data (HeckLit), and another centered on generating new data via automated high-throughput experimentation (Minerva).

Table 1: Framework Performance Comparison

| Feature | HeckLit Framework (Literature-Based) | Minerva Framework (HTE-Based) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Data Source | Historical literature data (HeckLit data set: 10,002 cases) [16] | Automated High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) [2] |

| Core Challenge Addressed | Sparse data distribution, high-yield preference in literature [16] | High-dimensional search spaces, resource-intensive optimization [2] |

| Key ML Strategy | Subset Splitting Training Strategy (SSTS) [16] | Scalable Multi-Objective Bayesian Optimization (q-NEHVI, q-NParEgo, TS-HVI) [2] |

| Reported Performance (R²) | R² = 0.380 (with SSTS) from a baseline of R² = 0.318 [16] | Identified conditions with >95% yield and selectivity for API syntheses [2] |

| Chemical Space Coverage | Large, spanning multiple reaction subclasses (~3.6 x 10¹² accessible cases) [16] | Targeted, exploring 88,000+ condition combinations for a specific transformation [2] |

| Validation Method | Retrospective benchmarking on literature data set [16] | Experimental validation in pharmaceutical process development [2] |

Table 2: Experimental Outcomes in Reaction Optimization

| Reaction Type | Framework | Key Outcome | Performance Compared to Traditional Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heck Reaction | HeckLit (with SSTS) | Improved model learning performance on a challenging yield data set [16] | Boosted predictive model accuracy (R² from 0.318 to 0.380) [16] |

| Ni-catalyzed Suzuki Reaction | Minerva | Achieved 76% area percent (AP) yield and 92% selectivity [2] | Outperformed two chemist-designed HTE plates which failed to find successful conditions [2] |

| Pd-catalyzed Buchwald-Hartwig Reaction | Minerva | Identified multiple conditions achieving >95% AP yield and selectivity [2] | Accelerated process development timeline from 6 months to 4 weeks in a case study [2] |

Experimental Protocols

The comparative performance of these frameworks is rooted in their distinct experimental methodologies.

HeckLit Data Set Construction and Model Training Protocol: The HeckLit data set was constructed by aggregating 10,002 Heck reaction cases from the literature. The model training protocol involved first establishing a baseline performance (R² = 0.318) on a standard test set. To address data sparsity, the Subset Splitting Training Strategy (SSTS) was implemented. This involved dividing the full data set into meaningful subsets based on reaction subclasses or conditions, training separate models on these subsets, and then leveraging the collective learning to boost the overall performance to an R² of 0.380 [16].

Minerva HTE and Multi-Objective Optimization Protocol: The Minerva framework initiates optimization with algorithmic quasi-random Sobol sampling to select an initial batch of experiments, ensuring diverse coverage of the reaction condition space [2]. Using this data, a Gaussian Process (GP) regressor is trained to predict reaction outcomes and their associated uncertainties. A scalable multi-objective acquisition function (e.g., q-NEHVI) then evaluates all possible reaction conditions to select the most promising next batch of experiments, balancing the exploration of unknown regions with the exploitation of high-performing ones. This process is repeated iteratively, with the chemist-in-the-loop fine-tuning the strategy as needed [2].

Visualizing the Machine Learning Workflows

The logical workflows of the HeckLit and Minerva frameworks, which are critical for understanding their approach to data scarcity, are visualized below.

Figure 1: The HeckLit SSTS workflow improves model learning by strategically dividing sparse data.

Figure 2: The Minerva framework uses an automated loop to generate data and optimize reactions.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Successfully implementing these ML-driven optimization campaigns requires a suite of specialized reagents and materials. The following table details key components used in the featured studies.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for ML-Optimized Catalysis

| Reagent/Material | Function in Optimization | Example Context |

|---|---|---|

| Nickel Catalysts | Earth-abundant, cost-effective alternative to precious palladium catalysts for cross-coupling reactions [2]. | Ni-catalyzed Suzuki reaction optimization [2]. |

| Ligand Libraries | Modular components that finely tune catalyst activity and selectivity; a key categorical variable in ML search spaces [2]. | Exploration in nickel-catalyzed Suzuki and Pd-catalyzed Buchwald-Hartwig reactions [2]. |

| Solvent Sets | Medium that influences reaction pathway, rate, and yield; a critical dimension for ML models to explore [17]. | High-dimensional search space component in HTE campaigns [2]. |

| Solid-Dispensing HTE Platforms | Automated systems enabling highly parallel execution of numerous miniaturized reactions for rapid data generation [2]. | Execution of 96-well plate HTE campaigns [2]. |

| Gaussian Process (GP) Regressors | ML models that predict reaction outcomes and quantify prediction uncertainty, guiding subsequent experiments [2]. | Core model within the Minerva Bayesian optimization workflow [2]. |

The challenge of data scarcity in reaction optimization is being met with sophisticated, data-centric strategies. The HeckLit framework demonstrates that novel algorithmic approaches like SSTS can extract significantly more value from existing, albeit sparse, literature data. In parallel, the Minerva framework shows that the integration of automated HTE with scalable Bayesian optimization can efficiently navigate vast reaction spaces, generating high-quality data de novo to solve complex problems in catalysis. For researchers, the choice between these approaches depends on the availability of historical data and access to automated experimentation resources. Both pathways offer a powerful departure from traditional, intuition-heavy methods, accelerating the development of efficient and sustainable chemical processes.

ML Methodologies in Action: Algorithms and Real-World Applications

The adoption of machine learning (ML) in reaction optimization has transformed the paradigm from traditional trial-and-error approaches to data-driven predictive science. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, selecting the appropriate algorithm is crucial for building accurate, interpretable, and efficient models. This guide provides an objective comparison of three cornerstone ML architectures—XGBoost, Random Forest, and Neural Networks—within the specific context of chemical reaction optimization. We evaluate their performance using recently published experimental data, detail standardized validation methodologies, and present a structured framework for algorithm selection based on specific research requirements. The comparative analysis focuses on predictive accuracy, computational efficiency, and interpretability, providing a evidence-based foundation for methodological decisions in reaction optimization research.

Performance Comparison: Quantitative Data from Recent Studies

The following tables summarize key performance metrics for XGBoost, Random Forest, and Neural Networks across various chemical reaction and materials science applications, as reported in recent literature.

Table 1: Comparative Model Performance for Yield Prediction Tasks

| Application Context | Best Performing Model | Key Performance Metrics | Comparative Model Performance | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glycerol Electrocatalytic Reduction (to Propanediols) | XGBoost (with PSO) | R²: 0.98 (Conversion Rate), 0.80 (Product Yield); Experimental validation error: ~10% | Outperformed other algorithms, demonstrated robustness against unbalanced datasets. | [18] |

| Cross-Coupling Reaction Yield Prediction | Message Passing Neural Network (MPNN) | R²: 0.75 | A type of Graph Neural Network; outperformed other GNN architectures (GCN, GAT, GIN). | [19] |

| Amide Coupling Condition Classification | Kernel Methods & Ensemble Architectures | High accuracy in classifying ideal coupling agent category | Performed "significantly better" than linear or single tree models. | [11] |

| Bentonite Swelling Pressure Prediction | GWO-XGBoost (Constrained) | R²: 0.9832, RMSE: 0.5248 MPa | Outperformed Feed-Forward and Cascade-Forward Neural Networks. | [20] |

| Software Effort Estimation | Improved Adaptive Random Forest | MAE improvement: 18.5%, RMSE improvement: 20.3%, R² improvement: 3.8% | Demonstrated the effect of advanced tuning on Random Forest performance. | [21] |

Table 2: Model Performance in Temporal and General Prediction Tasks

| Application Context | Best Performing Model | Key Performance Metrics | Comparative Model Performance | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vehicle Flow Time Series Prediction | XGBoost | Lower MAE and MSE | Outperformed RNN-LSTM, SVM, and Random Forest; better adapted to stationary series. | [22] |

| Esterification Reaction Optimization | XGBoost (Ensemble ML) | Test R²: 0.949, RMSE: 2.67% | Superior to linear regression (R²: 0.782); perfect ordinal agreement with ANOVA/SEM on factor importance. | [23] |

| Motor Sealing Performance Prediction | Hybrid Model (Polynomial Regression + XGBOOST) | Prediction Accuracy: within 2.881%, Computing Time: <1 sec | Massive efficiency improvement (32,400x) over Finite Element Analysis (9 hours). | [24] |

Experimental Protocols: Methodologies for Model Validation

To ensure the validity and reliability of model comparisons, the cited studies employed rigorous, standardized experimental protocols. The following methodologies provide a framework for reproducible research in ML-driven reaction optimization.

Data Curation and Preprocessing

A critical first step involves the assembly and preparation of high-quality datasets. For chemical reactions, this typically involves:

- Data Source Identification: Utilizing open-source databases like the Open Reaction Database (ORD) [11] or compiling datasets from published literature [18].

- Feature Selection: Incorporating a mix of operational factors (e.g., temperature, concentration, reaction time) [18] [23] and molecular descriptors. The latter can range from bulk material properties (e.g., molecular weight) to advanced structural features like Morgan Fingerprints and XYZ coordinates, which have been shown to boost model predictivity [11].

- Data Standardization: Applying filtering and cleaning scripts to create machine-readable datasets, a process crucial for handling heterogeneous reaction data [19] [11].

Model Training and Hyperparameter Tuning

The performance of any ML model is highly dependent on its parameter configuration.

- Baseline Establishment: A model with default parameters is built and evaluated to establish a performance benchmark [25] [21].

- Systematic Hyperparameter Search: Employing techniques like Grid Search or Randomized Search (e.g., via

GridSearchCVin scikit-learn) to explore the parameter space efficiently [25]. - Advanced Optimization Algorithms: For superior performance, studies often use sophisticated optimizers like Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) [18] [24] or Grey Wolf Optimization (GWO) [20] to fine-tune model hyperparameters, moving beyond traditional grid search.

Model Evaluation and Validation

Robust validation is essential to prevent overfitting and ensure model generalizability.

- Performance Metrics: Models are evaluated using task-relevant metrics. For regression (e.g., yield prediction), common metrics include R-squared (R²), Root Mean Square Error (RMSE), and Mean Absolute Error (MAE) [18] [22] [20]. For classification, accuracy is key [11].

- Cross-Validation: Using techniques like k-fold cross-validation to ensure reliable and unbiased performance estimates across different data splits [25].

- Experimental Validation: The most robust studies include wet-lab experiments to confirm model-predicted optimal conditions, typically reporting the error between predicted and experimental yields [18].

Model Interpretability and Explanation

Understanding model decisions builds trust and provides mechanistic insights.

- SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations): A unified framework used to quantify the contribution of each input feature to a model's prediction, applied across all three algorithm types [23] [21].

- Partial Dependence Plots (PDPs): Visualize the marginal effect of a feature on the predicted outcome, revealing non-linear relationships [21].

- Feature Importance Analysis: Tree-based models like XGBoost and Random Forest natively output feature importance scores, which can be validated against known chemical principles [23] [20].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

This table details key computational "reagents" and their functions, as utilized in the featured experiments for developing and validating ML models in reaction optimization.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for ML-Driven Reaction Optimization

| Research Reagent | Function in Model Development & Validation | Exemplary Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) | An optimization algorithm used for hyperparameter tuning, inspired by social behavior patterns like bird flocking. | Optimizing XGBoost parameters for predicting glycerol ECR conditions [18]. |

| SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) | A game-theoretic approach to explain the output of any ML model, quantifying feature importance. | Interpreting XGBoost models in esterification optimization [23] and software effort estimation [21]. |

| Morgan Fingerprints | A type of molecular representation that encodes the structure of a molecule as a bit or count vector based on its circular substructures. | Providing molecular environment features for amide coupling agent classification models [11]. |

| Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) | A class of neural networks designed to operate on graph-structured data, directly capturing molecular topology. | Predicting yields for cross-coupling reactions by representing molecules as graphs [19]. |

| Bayesian Optimization with Deep Kernel Learning (BO-DKL) | A probabilistic approach for globally optimizing black-box functions, here used for adaptive hyperparameter tuning. | Enhancing an Adaptive Random Forest model for software effort estimation [21]. |

Workflow and Algorithm Selection Pathways

The following diagram illustrates a standardized workflow for ML-driven reaction optimization, integrating the key experimental protocols and decision points for algorithm selection discussed in this guide.

The empirical data and methodologies presented in this guide demonstrate that there is no single "best" algorithm for all scenarios in reaction optimization. The choice is contextual, dependent on data characteristics, and the specific priorities of the research task. XGBoost consistently emerges as a high-performance choice for structured, tabular data, often delivering superior predictive accuracy for yield prediction and condition optimization [18] [22] [23]. Its success is attributed to efficient handling of complex feature interactions and robustness to unbalanced datasets. Random Forest remains a highly robust and interpretable alternative, particularly valuable for establishing strong baselines and mitigating overfitting, with its performance being significantly enhanced by advanced tuning strategies [25] [21]. Neural Networks, particularly specialized architectures like Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) and LSTMs, excel in scenarios involving non-tabular data, such as molecular graphs or sequential time-series data, where they can capture deep, hierarchical patterns [22] [19].

The future of ML in reaction optimization lies in hybrid approaches that leverage the complementary strengths of these algorithms. Furthermore, the integration of explainable AI (XAI) techniques like SHAP is becoming standard practice, transforming black-box models into sources of chemically intelligible insight and mechanistic understanding [23] [21]. As the field progresses, the systematic, multi-method validation framework outlined here will be crucial for developing reliable, trustworthy, and impactful predictive models in chemical and pharmaceutical research.

In the field of reaction optimization research, the scarcity of extensive, labeled datasets presents a significant bottleneck for developing accurate machine learning models. This challenge stands in stark contrast to how expert chemists operate, who successfully discover and develop new reactions by leveraging information from a small number of relevant transformations [26]. The disconnect between the substantial data requirements of conventional machine learning and the reality of laboratory research has driven the adoption of sophisticated strategies that can operate effectively in data-limited environments. Among these, transfer learning and active learning have emerged as powerful, complementary approaches that mirror the intuitive, hypothesis-driven processes of scientific discovery while providing a quantitative framework for accelerated experimentation.

Transfer learning addresses the data scarcity problem by leveraging knowledge gained from a data-rich source domain to improve learning in a data-poor target domain. This approach has shifted from a niche technique to a cornerstone of modern AI, enabling researchers to build effective models with fewer resources [27]. Meanwhile, active learning optimizes the data acquisition process itself by iteratively selecting the most informative experiments to perform, thereby maximizing knowledge gain while minimizing experimental burden [28]. When integrated into reaction optimization workflows, these strategies offer a pathway to robust model validation even when traditional large datasets are unavailable, making them particularly valuable for research environments with limited experimental resources.

Theoretical Foundations and Comparative Analysis

Core Conceptual Frameworks

Transfer Learning operates on the principle that knowledge gained while solving one problem can be applied to a different but related problem. In chemical contexts, this typically involves pretraining a model on a large, general reaction dataset (source domain) followed by fine-tuning on a smaller, specific dataset of interest (target domain) [26]. This paradigm allows models to leverage fundamental chemical principles learned from broad data while specializing for particular reaction systems. The process encompasses several key components: the source domain with its associated knowledge, the target domain representing the specific problem, and the transfer learning algorithm that facilitates knowledge translation between them.

Active Learning adopts a different approach by focusing on strategic data selection. Instead of using a static dataset, active learning employs a iterative cycle where a model guides the selection of which experiments to perform next based on their potential information gain [29]. The core mechanism involves an acquisition function that quantifies the potential value of candidate experiments, typically prioritizing data points where the model exhibits high uncertainty or which diversify the training distribution. This creates a closed-loop experimentation system that progressively improves model accuracy while minimizing the total number of experiments required [28].

Strategic Comparison and Performance Metrics

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Transfer Learning and Active Learning Approaches

| Aspect | Transfer Learning | Active Learning |

|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Leverages knowledge from related tasks/domains | Selects most informative data points for labeling |

| Data Requirements | Source domain: Large datasets; Target domain: Smaller specialized sets | Starts with minimal seed data, expands strategically |

| Computational Focus | Prior knowledge transfer and model adaptation | Optimal experimental design and uncertainty quantification |

| Key Applications | Fine-tuning pretrained models for specific reaction classes [26] | Characterizing new reactor configurations [28]; Reaction yield prediction [29] |

| Performance Metrics | Prediction accuracy on target task after fine-tuning | Learning efficiency (accuracy gain per experiment); Model uncertainty reduction |

| Typical Outcomes | 27-40% accuracy improvement in specialized tasks [26] | 39% to 90% forecasting accuracy improvement in 5 iterations [28] |

The quantitative performance of these approaches demonstrates their effectiveness in low-data scenarios. In one documented case, a transformer model pretrained on approximately one million generic reactions and fine-tuned on a smaller carbohydrate chemistry dataset of approximately 20,000 reactions achieved a top-1 accuracy of 70% for predicting stereodefined carbohydrate products. This represented an improvement of 27% and 40% from models trained only on the source or target data, respectively [26]. Meanwhile, active learning implementations have shown remarkable efficiency, with one framework for mass transfer characterization achieving a progression from 39% to 90% forecasting accuracy after just five active learning iterations [28].

Experimental Protocols and Implementation

Transfer Learning Methodology for Reaction Yield Prediction

The implementation of transfer learning for chemical reaction optimization follows a structured protocol that enables effective knowledge transfer from data-rich source domains to specific target applications:

Step 1: Source Model Pretraining

- Curate a large, diverse dataset of chemical reactions (e.g., 1+ million reactions from public databases like USPTO) [26]

- Train a base model (typically transformer-based architectures) for general reaction prediction tasks

- Validate model performance on held-out test sets from the source domain

Step 2: Target Domain Adaptation

- Assemble a specialized dataset relevant to the target application (typically 20,000 reactions or fewer) [26]

- Initialize the target model with weights from the pretrained source model

- Fine-tune the model on the target dataset using a reduced learning rate to prevent catastrophic forgetting

- Employ early stopping based on target validation performance to avoid overfitting

Step 3: Model Validation and Deployment

- Evaluate the fine-tuned model on an independent test set from the target domain

- Assess comparative performance against models trained from scratch or on source/target data only

- Deploy the validated model for prospective prediction in the target reaction space

This protocol successfully bridges the data availability gap by transferring fundamental chemical knowledge while allowing specialization for specific reaction systems. The fine-tuning process typically requires careful hyperparameter optimization, particularly regarding learning rate scheduling and early stopping criteria to balance knowledge retention and adaptation.

Active Learning Framework for Reaction Space Exploration

The experimental implementation of active learning for reaction optimization follows an iterative, closed-loop workflow that integrates machine learning with physical experimentation:

Step 1: Initialization Phase

- Define the reaction space encompassing all possible combinations of reactants, catalysts, solvents, and conditions [29]

- Select an initial seed set of reactions (typically 2.5-5% of the total space) through random sampling or based on prior knowledge [29]

- Execute experiments for the seed set and record yields or other performance metrics

Step 2: Iterative Active Learning Cycle

- Model Training: Develop a predictive model using all available experimental data

- Uncertainty Quantification: Estimate prediction uncertainty across the unexplored reaction space using ensemble methods or other uncertainty quantification techniques [28]

- Acquisition Function Application: Apply a diversified uncertainty-based selection criterion to identify the most informative next experiments, balancing exploration and exploitation [28]

- Experimental Execution: Perform the selected reactions and measure outcomes

- Model Update: Retrain the model with the expanded dataset

Step 3: Termination and Validation

- Continue iterations until predefined performance thresholds are met or experimental budget is exhausted

- Validate final model performance on held-out test reactions

- Apply the optimized model to identify high-performing regions of the reaction space

This framework has demonstrated remarkable efficiency in practical applications, with one implementation achieving promising prediction results (over 60% of predictions with absolute errors less than 10%) while querying only 5% of the total reaction combinations [29]. The key to success lies in the acquisition function design, which in advanced implementations incorporates diversity metrics alongside uncertainty to ensure comprehensive space exploration.

Visualization of Methodologies

ML Strategies for Low-Data Scenarios

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Research Materials and Computational Tools for Implementation

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Reaction Databases | USPTO, Pfizer's Suzuki coupling dataset [29], Buchwald-Hartwig coupling dataset [29] | Source domains for transfer learning; benchmark datasets for method validation |

| Computational Frameworks | Transformer architectures [26], XGBoost [18], Bayesian optimization tools [29] | Core algorithms for model development, prediction, and experimental selection |

| Uncertainty Quantification Methods | Ensemble neural networks [28], Bayesian neural networks | Estimation of prediction uncertainty to guide active learning acquisition functions |

| Chemical Representation Methods | Molecular descriptors, reaction fingerprints [29], N-grams and cosine similarity [30] | Featurization of chemical structures and reactions for machine learning input |

| Experimental Automation | High-throughput experimentation systems [29], automated reactor platforms [28] | Acceleration of experimental iterations required for active learning cycles |

| Validation Metrics | Prediction accuracy (R², MAE) [18], uncertainty calibration, learning efficiency curves | Quantitative assessment of model performance and experimental efficiency |

The successful implementation of these advanced strategies requires careful selection and integration of these research reagents. For transfer learning, the choice of source dataset significantly impacts final performance, with domain-relevant sources generally yielding better transfer efficacy [26]. For active learning, the experimental platform must balance throughput with reliability, as the iterative nature of the approach depends on rapid turn-around of experimental results to inform subsequent cycles [28].

Comparative Performance Analysis

Quantitative Benchmarking Across Domains

Table 3: Experimental Performance Metrics Across Application Domains

| Application Domain | Method | Key Performance Metrics | Comparative Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reaction Yield Prediction | RS-Coreset (Active Learning) | Absolute error <10% for 60% of predictions [29] | Achieved with only 5% of total reaction space explored [29] |

| Mass Transfer Characterization | Diversified Uncertainty-based AL | Forecasting accuracy improvement: 39% to 90% [28] | Completed in 5 active learning iterations [28] |

| Stereoselectivity Prediction | Transfer Learning | Top-1 accuracy: 70% for carbohydrate chemistry [26] | 27-40% improvement over non-transfer approaches [26] |

| Electrochemical Conversion | XGBoost with PSO optimization | R²: 0.98 for conversion rate; 0.80 for product yield [18] | Outperformed other algorithms on unbalanced datasets [18] |

| Data Leakage Detection | Active Learning | F-2 score: 0.72 [31] | Reduced annotated sample requirement from 1,523 to 698 [31] |

The empirical evidence demonstrates that both transfer learning and active learning can deliver substantial performance gains in low-data regimes, though through different mechanisms and with distinct application profiles. Transfer learning excels when substantial source data exists for related domains, effectively bootstrapping specialized models with limited target data. The reported 27-40% accuracy improvements for stereoselective reaction prediction highlight its value for specializing general chemical knowledge to specific reaction classes [26].

Active learning demonstrates remarkable data efficiency, achieving high-fidelity predictions while exploring only a fraction of the total experimental space. The documented case where querying just 5% of reaction combinations yielded predictions with less than 10% error for 60% of the space illustrates the profound experimental savings possible with strategic data selection [29]. This makes active learning particularly valuable for initial exploration of novel reaction systems or when experimental resources are severely constrained.

Integrated Approaches and Future Projections

The most advanced implementations begin to combine these strategies, using transfer learning to initialize models that are then refined through active learning cycles. This hybrid approach leverages the strengths of both methods: the prior knowledge incorporation of transfer learning and the data-efficient optimization of active learning. As these methodologies mature, they are projected to become default components of AI-driven research pipelines, democratizing access to powerful machine learning tools while reducing computational and experimental costs [27].

The future evolution of these strategies will likely focus on improved uncertainty quantification, more sophisticated acquisition functions that balance multiple objectives, and enhanced transfer learning techniques that can identify the most relevant source domains for specific target problems. As these technical advances mature, they will further solidify the role of machine learning in reaction optimization research, enabling more efficient exploration of chemical space and accelerating the development of novel synthetic methodologies.

The optimization of enzymatic reaction conditions is a critical yet challenging step in biocatalysis, impacting industries from pharmaceutical synthesis to biofuel production. The efficiency of an enzyme is governed by a multitude of interacting parameters—including pH, temperature, and substrate concentration—that must be precisely tuned to maximize performance metrics like turnover number (TON) or yield. This creates a high-dimensional optimization landscape that is difficult to navigate with traditional methods. Approaches like one-factor-at-a-time (OFAT) are inefficient as they ignore parameter interactions, while Response Surface Methodology (RSM) requires an exponentially growing number of experiments as variables increase, making it resource-intensive [26] [32]. Machine learning, particularly Bayesian Optimization (BO), has emerged as a powerful, sample-efficient strategy for global optimization of these complex "black-box" functions, enabling researchers to identify optimal conditions with dramatically fewer experiments [32] [33]. This case study examines the application and validation of Bayesian Optimization for enzymatic reaction optimization, comparing its performance against traditional RSM and highlighting its integral role in self-driving laboratories [8].

Bayesian Optimization: Core Principles and Workflow

The Conceptual Framework

Bayesian Optimization (BO) is a sequential strategy for global optimization of expensive-to-evaluate black-box functions. It is particularly suited for biological applications because it makes minimal assumptions about the objective function (requiring only continuity), does not rely on gradients and can handle the inherent noise and rugged landscapes of enzymatic systems [33]. The power of BO stems from its three core components:

- A Probabilistic Surrogate Model: Typically a Gaussian Process (GP), which uses observed experimental data to build a probabilistic map of the entire parameter space. For any set of untested conditions, the GP provides a prediction (mean) and a measure of uncertainty (variance) [33].

- An Acquisition Function: A decision-making function that uses the surrogate model's predictions to balance the trade-off between exploration (sampling regions of high uncertainty) and exploitation (sampling regions with high predicted performance). Common acquisition functions include Expected Improvement (EI) and Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) [32] [33].

- Bayesian Inference: The iterative process of updating the surrogate model with new experimental results, refining the model's understanding of the landscape with each cycle [33].

A Standardized Workflow for Enzymatic Reactions

The following diagram illustrates the iterative, closed-loop workflow of a Bayesian Optimization campaign for enzymatic reaction optimization.

Performance Comparison: Bayesian Optimization vs. Traditional Methods

Quantitative Benchmarking in Biocatalysis

A direct comparative study benchmarked a customized Bayesian Optimization Algorithm (BOA) against a commercial RSM tool (MODDE) for optimizing the Total Turnover Number (TON) in two enzymatic reactions: a benzoylformate decarboxylase (BFD)-catalyzed carboxy-lyase reaction and a phenylalanine ammonia lyase (PAL)-catalyzed amination [32]. The results, summarized in the table below, demonstrate the superior efficiency and performance of BOA.

Table 1: Benchmarking BOA vs. RSM for Enzymatic TON Optimization [32]

| Reaction & Metric | RSM (MODDE) | Bayesian Optimization (BOA) | Performance Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| BFD-Catalyzed Reaction | |||

| Predicted TON | 2,776 | Not Applicable | |

| Experimentally Achieved TON | 3,289 | 5,909 | 80% vs. RSM |

| PAL-Catalyzed Reaction | |||

| Experimentally Achieved TON | 1,050 | 2,280 | 117% vs. RSM |

| General Efficiency | |||

| Experimental Strategy | Single-iteration, space-filling | Iterative, intelligent sampling | Up to 360% improvement vs. other BO methods |

The study demonstrated that BOA could successfully navigate the complex parameter interactions. For the BFD reaction, BOA identified an optimal TPP cofactor concentration that was likely inhibiting at higher levels—a nuance that RSM failed to capture fully. Furthermore, the BOA workflow achieved this with a similar or lower total number of experiments than the RSM-directed approach, showcasing its sample efficiency [32].

Broader Validation and Self-Driving Laboratories

The efficacy of Bayesian Optimization extends beyond individual reactions to integrated self-driving laboratory (SDL) platforms. One study developed an SDL that conducted over 10,000 simulated optimization campaigns to identify the most efficient machine learning algorithm for enzymatic reaction optimization. The results confirmed that a finely-tuned BO algorithm was highly generalizable and could autonomously and rapidly determine optimal conditions across multiple enzyme-substrate pairs with minimal human intervention [8].

Another validation involved a retrospective analysis of a published metabolic engineering dataset where a four-dimensional transcriptional system was optimized for limonene production. The BO policy converged to within 10% of the optimal normalized Euclidean distance after investigating only 18 unique data points, whereas the original study's grid-search method required 83 points. This represents a 76% reduction in experimental effort, a crucial advantage when experiments are time-consuming or costly [33].

Experimental Protocols and Reagent Solutions

Detailed Methodology from a Benchmarking Study

The following protocol is adapted from a study that directly compared BOA and RSM for optimizing enzyme-catalyzed reactions [32].

Objective: Maximize the Total Turnover Number (TON) for a model enzymatic reaction. Enzymes & Reactions:

- BFD Reaction: Benzoylformate decarboxylase (BFD)-catalyzed carboxy-lyase reaction.

- PAL Reaction: Phenylalanine ammonia lyase (PAL)-catalyzed conversion of trans-cinnamic acid and ammonia to phenylalanine.

Experimental Variables:

- The five continuous parameters optimized for both reactions were: pH, temperature, enzyme concentration, substrate concentration, and cosolvent (DMSO) concentration. The BFD reaction also included thiamine pyrophosphate (TPP) concentration as a sixth variable.

Procedure:

- Initialization: The range for each experimental variable was defined. A small initial dataset (e.g., 5-10 data points) was generated either from preliminary experiments or historical data.

- RSM Workflow: Using MODDE software, an experimental table was generated (e.g., 29 runs for the BFD reaction). All experiments were conducted in a single batch. The software then built a quadratic response surface model to predict the optimal conditions.

- BOA Workflow:

- The initial dataset was used to train the first Gaussian Process surrogate model.

- The acquisition function (an improved Expected Improvement algorithm was used in BOA) selected the most promising set of conditions to test next.

- The experiment was run under these conditions, and the resulting TON was measured.

- The new data point was added to the dataset, and the Gaussian Process model was updated.

- Steps b-d were repeated for a set number of iterations or until performance converged.

- Validation: The optimal conditions identified by both RSM and BOA were experimentally validated, and the final TON values were compared.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Materials for Enzymatic Optimization Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function in Optimization | Example from Case Studies |

|---|---|---|

| Enzyme (Wild-type or Mutant) | The biocatalyst whose performance is being optimized. | Benzoylformate decarboxylase (BFD), Phenylalanine ammonia lyase (PAL) [32]. |

| Substrates | The starting materials converted in the enzymatic reaction. | Benzoylformate (for BFD), trans-Cinnamic acid & Ammonia (for PAL) [32]. |

| Cofactors | Non-protein compounds required for enzymatic activity. | Thiamine pyrophosphate (TPP) for BFD [32]. |

| Buffer Systems | Maintains the pH, a critical parameter for enzyme stability and activity. | Various buffers to cover a defined pH range (e.g., 7-9) [32]. |

| Cosolvents | Improves solubility of hydrophobic substrates in aqueous reaction mixtures. | Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) [32]. |

| Analytical Instrumentation | Quantifies reaction outcomes (yield, TON, selectivity). | Plate readers (UV-Vis), UPLC-MS systems for high-throughput analysis [8]. |

| Automation Hardware | Enables high-throughput and reproducible execution of experiments. | Liquid handling robots, robotic arms for labware transport [8]. |

This case study demonstrates that Bayesian Optimization is not merely an incremental improvement but a paradigm shift in the optimization of enzymatic reactions. The experimental data confirms that BO consistently outperforms traditional Response Surface Methodology, achieving significantly higher turnover numbers—up to 117% improvement in one case—while simultaneously reducing the number of experiments required. Its ability to efficiently navigate high-dimensional, interacting parameter spaces makes it uniquely suited for complex biocatalytic systems. The integration of BO into self-driving laboratories represents the future of biochemical experimentation, enabling fully autonomous, data-driven optimization cycles. As machine learning models continue to evolve, their validation and application through robust frameworks like Bayesian Optimization will be central to accelerating discovery and development in synthetic biology and pharmaceutical research.

In the pursuit of sustainable energy, biodiesel has emerged as a crucial renewable alternative to fossil fuels. The optimization of biodiesel production processes, however, is complex due to numerous interdependent parameters including catalyst concentration, reaction temperature, and methanol-to-oil ratio. Traditional optimization methods often struggle to capture the non-linear relationships between these variables. Machine learning (ML) has demonstrated superior capability in modeling these complex interactions, achieving predictive accuracies with R² values up to 0.98 in some biodiesel production applications [34]. Nevertheless, the "black box" nature of many advanced ML models has limited their interpretability and, consequently, their trusted adoption in research and industrial settings.

SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) analysis has emerged as a powerful solution to this interpretability challenge. Based on cooperative game theory, SHAP quantifies the contribution of each input feature to a model's prediction, thereby providing a unified framework for explaining complex ML models [34]. This case study examines how SHAP analysis is being integrated with ML models to optimize biodiesel production processes, focusing on its methodological application, insights generated, and validation within the broader context of machine learning model trustworthiness for reaction optimization research.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Catalyst Synthesis and Biodiesel Production Framework

The foundational experimental protocols across the cited studies follow a consistent pattern of catalyst preparation, biodiesel production, and analytical validation. In one representative study, a reusable CaO catalyst was synthesized from waste eggshells through a multi-stage process: the shells were thoroughly cleaned with distilled water, air-dried, and heated in a furnace at 60°C for 12 hours to facilitate brittleness. The material was then mechanically comminuted using planetary ball milling to achieve uniform particle size distribution, followed by calcination at 600°C for 6 hours to convert calcium carbonate (CaCO₃) into reactive calcium oxide (CaO) [35].

For biodiesel production, waste cooking oil (WCO) was pre-treated through filtration and heating to remove suspended impurities and moisture. Due to high free fatty acid (FFA) content, an acid-catalyzed esterification pre-treatment was often necessary, using sulfuric acid (1 wt%) and methanol (20 vol%) at 70°C with continuous stirring to reduce FFA levels. The subsequent transesterification reaction was conducted in a three-necked round-bottom flask equipped with a reflux condenser, mechanical stirrer, and digital thermometer. The reaction parameters—typically catalyst concentration (1-3 wt%), methanol-to-oil molar ratio (6:1 to 12:1), and reaction temperature (55-65°C)—were systematically varied according to experimental designs, with continuous stirring at 600 rpm for a fixed duration of 60 minutes [36]. After reaction completion, the mixture was transferred to a separating funnel and allowed to settle for 12 hours, enabling gravity separation of biodiesel (upper layer) from glycerol (lower layer). The biodiesel phase was then carefully decanted and repeatedly washed with warm distilled water to remove catalyst residues, soap, and methanol before final drying.

Machine Learning Integration and SHAP Implementation

The integration of machine learning with SHAP analysis follows a structured workflow. In the data preparation phase, experimental datasets are constructed with key process parameters as input features and biodiesel yield as the target output. The studies typically employed dataset sizes ranging from 16 experimental runs to 1307 data points, with outlier detection algorithms like Monte Carlo Outlier Detection (MCOD) applied to ensure data reliability [37].

For model development, multiple ML algorithms are trained and evaluated using k-fold cross-validation (typically k=5) to prevent overfitting and ensure robustness. Commonly implemented algorithms include Gradient Boosting (GB), CatBoost, XGBoost, Random Forest, Support Vector Regression (SVR), and Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs). Hyperparameter tuning is performed via grid search or Bayesian optimization to maximize predictive performance [35] [34] [36].

Once the optimal model is identified, SHAP analysis is implemented to interpret the model's decision-making process. The SHAP framework calculates the marginal contribution of each feature to every prediction, then averages these contributions across all possible feature combinations. This generates SHAP values that quantify feature importance and direction of effect, which can be visualized through summary plots, dependence plots, and force plots [34].

Comparative Performance of ML Models with SHAP Interpretation

Model Accuracy and Robustness Assessment